Abstract

Vaccination with peptide 10 (P10), derived from the Paracoccidioides brasiliensis glycoprotein 43 (gp43), induces a Th1 response that protects mice in an intratracheal P. brasiliensis infection model. Combining P10 with complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) or other adjuvants further increases the peptide's antifungal effect. Since dendritic cells (DCs) are up to 1,000-fold more efficient at activating T cells than CFA, we examined the impact of P10-primed bone-marrow-derived DC vaccination in mice. Splenocytes from mice immunized with P10 were stimulated in vitro with P10 or P10-primed DCs. T cell proliferation was significantly increased in the presence of P10-primed DCs compared to the peptide. The protective efficacy of P10-primed DCs was studied in an intratracheal P. brasiliensis model in BALB/c mice. Administration of P10-primed DCs prior to (via subcutaneous vaccination) or weeks after (via either subcutaneous or intravenous injection) P. brasiliensis infection decreased pulmonary damage and significantly reduced fungal burdens. The protective response mediated by the injection of primed DCs was characterized mainly by an increased production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and interleukin 12 (IL-12) and a reduction in IL-10 and IL-4 compared to those of infected mice that received saline or unprimed DCs. Hence, our data demonstrate the potential of P10-primed DCs as a vaccine capable of both the rapid protection against the development of serious paracoccidioidomycosis or the treatment of established P. brasiliensis disease.

INTRODUCTION

Paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM) is a systemic granulomatous disease initiated by the inhalation of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis conidia, a thermally dimorphic fungus. It is widespread in Latin America, affecting mainly rural workers. Systemic mycoses are the 10th leading cause of death due to infectious diseases in Brazil (26, 27). Notably, approximately 1,853 (∼51.2%) of 3,583 confirmed deaths in Brazil due to systemic mycoses from 1996 to 2006 were caused by PCM (31). However, since PCM is not yet included in the national mandatory disease notification system, the true annual incidence of clinically significant PCM in Brazil is not known.

First described by Puccia et al. in 1986 (33), the immunologically dominant glycoprotein of 43 kDa, gp43, is currently the major diagnostic antigen of P. brasiliensis (12). The gp43 gene has been cloned and sequenced (11). It encodes a polypeptide of 416 amino acids (Mr of 45,947) with a leader peptide of 35 residues, and the mature protein has a single high mannose N-glycosylated site (11). A B cell-reacting epitope in gp43 has been suggested (8, 43), and the H-2d restricted T-cell epitope has been mapped to a 15-mer peptide called peptide 10 (P10) (39). Different 12-mer sequences containing the hexapeptide HTLAIR induce proliferation of lymph node cells from mice sensitized to gp43 or infected with P. brasiliensis, and the lymphoproliferation induced by either P10 or gp43 involves type 1 CD4+ T-helper lymphocytes. Immunoprotection experiments have been carried out with both gp43 and P10 in combination with complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA). Both gp43 and P10 with CFA induce significant protective responses, as immunized mice studied 3 months after intratracheal infection with virulent P. brasiliensis yeast cells displayed preserved lung architecture and few or no yeasts (39). In contrast, nonimmunized mice had large numbers of yeasts within epithelioid granulomas in all lung fields.

Immunoprotection by P10 is related to an IFN-γ-producing Th-1 response, since P10 immunization of IFN-γ or IFN-γR and interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) knockout mice was not protective (42). The key role of IFN-γ in organizing granulomas to contain P. brasiliensis yeasts has been well characterized by other research groups (6, 7, 9, 20, 28).

P10 has been validated as a vaccine candidate based on the presentation of P10 by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules from different murine haplotypes (41) as well as by human HLA-DR molecules similarly with other promiscuous peptides derived from gp43 (19). Examination of gp43 molecules from many different isolates has shown that P10 is highly conserved in nature, with the exception of Paracoccidioides lutzii (32, 40), which recently has been separated from P. brasiliensis as a species. Additionally, P10 has been shown to be immunoprotective even in formulations that do not require CFA, such as with P10 combined with poly(lactic acid-glycolic acid) nanoparticles (2).

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most effective antigen-presenting cells and are distributed in the majority of tissues. Once active, DCs express costimulatory molecules that may promote or regulate T-cell interaction. T-cell activation and proliferation can lead to immunity or to tolerance, thus generating effector or regulatory T cells and different patterns of cytokines (36, 37).

The regulation of T-cell response by DCs in systemic and subcutaneous mycosis has been studied in Histoplasma capsulatum (15), Coccidioides posadasii (13), Sporothrix schenckii (44), and P. brasiliensis (1). The role of DCs in vaccination is a promising area for study. Presently, we studied the impact of the transference of DCs primed with P10 to mice prior to or after intratracheal (i.t.) challenge with the virulent Pb18 isolate of P. brasiliensis. We show that administration of P10-primed DCs is therapeutic in mice with established PCM. Furthermore, we demonstrate that P10-primed DCs given prior to challenge with P. brasiliensis significantly attenuate subsequent disease. Hence, P10-primed DCs appear to be an excellent candidate for further study as a potential therapeutic for severe cases of PCM in human patients or for development as a prophylactic for individuals at risk for severe disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal use and ethics statement.

BALB/c, 6- to 8-week-old male mice were bred at the University of São Paulo animal facility under specific pathogen-free conditions. All animals were handled in accordance with good animal practice as defined by the relevant national animal welfare bodies, and all in vivo testing was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of São Paulo.

Fungal strain.

Virulent P. brasiliensis Pb18 yeast cells were maintained by weekly passages on solid Sabouraud medium at 37°C and were used after 7 to 10 days of growth. Before experimental infection, the cultures were grown in modified McVeigh-Morton medium (MMcM) at 37°C for 5 to 7 days (33). The fungal cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2) and counted in a hemocytometer. The viability of fungal suspensions, determined according to methods described previously by staining with Janus green B (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), was always higher than 90% (21).

Dendritic cells.

Bone-marrow-derived DCs were generated according to previously described methods (18, 23). Briefly, femurs and tibias were flushed with 5 ml of RPMI. Bone marrow cells were differentiated into DCs by culturing in RPMI (Vitrocell, Campinas, Brazil) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Vitrocell), 20 μg/ml gentamicin (Gibco BRL Life Technologies, NY), and recombinant cytokines GM-CSF (30 ng/ml) and IL-4 (15 ng/ml), both from Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, for seven days. On the third day, nonadherent cells were removed and further incubated with fresh medium and growth factors. On the fifth day, the supernatant was centrifuged, the pellet was plated again, and the medium with growth factors was replaced. On the seventh day, the nonadherent cells were removed and analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS; BD FACSCanto) using DC cell surface markers. Approximated 70% of the cells were CD11c+ MHC class II+. The other cells (30%) were granulocytes, lymphocytes, and macrophages. The macrophages displayed an immature phenotype, with no expression of MHC-II, CD80, or CD86 (data not shown).

In vitro cell proliferation induced by P10-pulsed DCs.

Peptide P10 was produced as described previously (39) and diluted in PBS with 20% of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Footpads of mice were injected with either 10.2 μM P10 (group 1) or PBS only (control, group 2). After 7 days, the spleens were harvested and the splenocytes were dispersed manually. The cells were collected by centrifugation (450 × g), and the pellets were suspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 20 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM HEPES, 20 μg/ml gentamicin, 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 5 mM sodium pyruvate, and 100 mM nonessential amino acids with 1% fetal calf serum (FCS). The splenocytes of immunized or control mice were cultured in flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plates at a final concentration of 4 × 105 cells/well. DCs were added to the designated wells at a 3:1 DC-to-spleen-cell ratio. The following controls were used: spleen cells alone, with P10 only, or with P10-primed DCs. The P10-primed DCs were generated by incubating 3 × 105 DCs for 2 h with 2.55 μM P10. Concanavalin A-primed DCs were also used as a control. The plates were incubated for 72 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Proliferation was determined using 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays as described previously (29), and the results (based on the optical density) are means of triplicate determinations.

Intratracheal infection of BALB/c mice.

BALB/c mice were inoculated intratracheally (i.t.) with virulent P. brasiliensis Pb18. Briefly, mice were anesthetized intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 200 μl of a solution containing 80 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg of xylazine, both from União Química Farmacêutica, Brazil. For inoculation, a mouse's neck was hyperextended, the trachea was exposed at the level of the thyroid, and 3 × 105 yeast cells in PBS were injected i.t. using a 26-gauge needle. A maximum of 50 μl was inoculated per mouse. Incisions were sutured with 5-0 silk.

Transference of P10-pulsed DCs into infected mice with P. brasiliensis.

Priming of DCs was achieved by incubating 3 × 105 DCs with 2.55 μM P10 for 2 h. The DCs were washed three times with PBS prior to use in immunization regimens. For the therapeutic protocols, animals were infected i.t. with 3 × 105 yeast cells, and they subsequently received 2 doses of 3 × 105 DCs primed with P10 in 50 μl PBS on days 31 and 38 after infection. Groups of mice were immunized by either intravenous (via tail vein) or subcutaneous (footpad) injection of DCs. These mice were sacrificed 7 days after the second immunization, at day 45 after infection. We also examined the impact of a single subcutaneous immunization at day 15 after infection in which mice were sacrificed 7 days later, at day 21 after infection. For the prophylactic protocol, mice were immunized by either intravenous (via tail vein) or subcutaneous (footpad) routes with 3 × 105 DCs pulsed with P10 in 50 μl PBS and then infected i.t. 24 h after immunization. The mice in the prophylactic protocol were sacrificed 30 days after infection. For both the treatment and prophylactic protocols, control groups included mice that received only PBS or unprimed DCs.

Fungal burden in organs of infected mice.

Mice were sacrificed at the specified days after i.t. infection, and fungal burdens were determined by CFU. Sections of lungs were removed, weighed, and homogenized in 1 ml of PBS. Samples (100 μl) were plated on solid brain heart infusion (BHI) medium supplemented with 4% fetal calf serum (Gibco, NY), 5% spent P. brasiliensis (strain 192) culture medium, 10 IU/ml streptomycin-penicillin (Cultilab, Brazil), and 500 mg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (10). Petri dishes were incubated at 37°C for at least 10 days, and colonies were counted (1 colony = 1 CFU).

Histopathological analyses.

Sections of murine lungs were also fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin for sectioning. The sections were stained by the Gomori-Grocott method and examined microscopically.

Cytokine detection.

Sections of excised lungs were homogenized in 2 ml of PBS in the presence of protease inhibitors: benzamidine HCl (4 mM), EDTA disodium salt (1 mM), N-ethylmaleimide (1 mM), and pepstatin (1.5 mM) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The supernatants were assayed for IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, and IFN-γ using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (BD OpTeia, San Diego, CA). The detection limits of the assays were as follows: 7.8 pg/ml for IL-4, 31.3 pg/ml for IFN-γ and IL-10, and 62.5 pg/ml for IL-12, as previously determined by the manufacturer.

Statistical analysis.

Results were analyzed using GraphPad 5.0 software (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA). Statistical comparisons were made by analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) followed by a Tukey-Kramer posttest. All values were reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). P values of <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

RESULTS

Cell proliferation induced by P10-primed DCs.

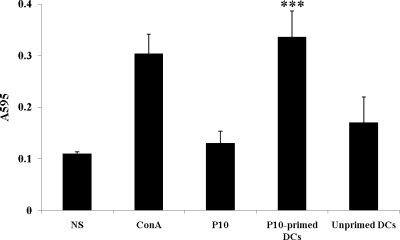

The ability of P10-primed DCs to induce cell proliferation of splenocytes from animals previously immunized with P10 was demonstrated. Splenocytes from BALB/c mice previously immunized subcutaneously with P10 were isolated and cocultured in the presence of P10 at 2.55 μM or with P10-primed DCs. Coculture with in vitro P10-primed DCs induced a 3-fold-higher proliferation than splenocytes incubated with P10 alone (Fig. 1). The proliferation of splenocytes incubated with P10 alone was similar to that of controls without antigen.

Fig 1.

Cell proliferation assay. Splenocytes isolated from BALB/c mice previously immunized subcutaneously with 10.2 μM P10 were stimulated in vitro for 72 h with 2.55 μM P10 or with P10-primed DCs or nonprimed DCs. NS, nonstimulated splenocytes; ConA, positive-control activation of splenocytes with the mitogen concanavalin A. Each bar shows the mean of results from 3 experiments carried out on different days. ∗∗∗, significant difference (P < 0.0001; determined by analysis of variance [2-way ANOVA] and the posttest of Tukey-Kramer) relative to the free P10 stimulated system.

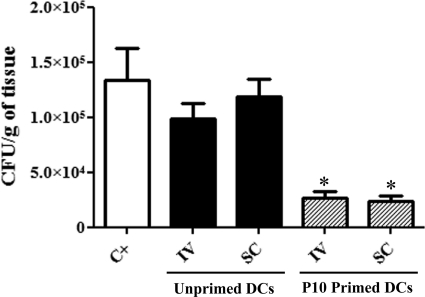

Immunization with P10-primed DCs reduces fungal burden.

We used several protocols to evaluate whether immunization with P10-pulsed DCs could reduce fungal burdens. The experiments were performed three different times, with a total of 15 animals for each group tested. In the therapeutic protocol, where treatment was initiated after 30 days of infection, the two injections of P10-primed DCs were sufficient to significantly reduce the fungal burden in the lungs of infected mice compared to the fungal burden in the lungs of those that did not receive any treatment or were injected with unprimed DCs (Fig. 2). We also observed that both routes of administration of the P10-primed DCs, intravenous and subcutaneous, produced similar results. We also tested a therapeutic protocol in which the animals were infected i.t. and after 15 days of infection were treated with one dose of P10-primed DCs and sacrificed 7 days after immunization. The results of this protocol were similar to those observed with the previous therapeutic protocol after 30 days of infection (data not shown).

Fig 2.

Lung CFU: therapeutic protocol. The results are from two independent experiments. Each group from each experiment (n = 5) was infected i.t. with 3 × 105 yeast cells. After 30 days, groups of mice received either nonprimed dendritic cells (DCs) or P10-primed DCs via either an intravenous (IV) or subcutaneous (SC) route. A second identical immunization was administered 7 days later. The control group (C+) was not treated. Mice were sacrificed at day 45 after infection. ∗, significant difference (P < 0.05) compared with the control and unprimed DCs.

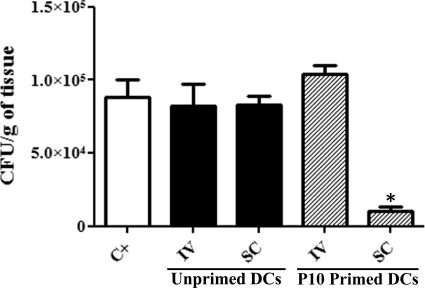

However, in a prophylactic protocol (Fig. 3), different results were obtained depending on route of vaccination. Notably, a significant reduction of the fungal burden in the lungs was achieved when mice were immunized with the P10-primed DCs subcutaneously prior to infection. In contrast, mice intravenously immunized with the P10-primed DCs had fungal burdens similar to those of the infected control animals.

Fig 3.

Lung CFU: prophylactic protocol. The results are from two independent experiments. The groups of treated mice (n = 5 per experiment) received either unprimed dendritic cells (DC) or P10-primed DCs via either intravenous (IV) or subcutaneous (SC) route 24 h before the mice were infected i.t. with 3 × 105 yeast cells. The control (C+) group received PBS 1 day prior to infection. Mice were sacrificed 30 days after infection. ∗, significant difference (P < 0.001) compared with the control.

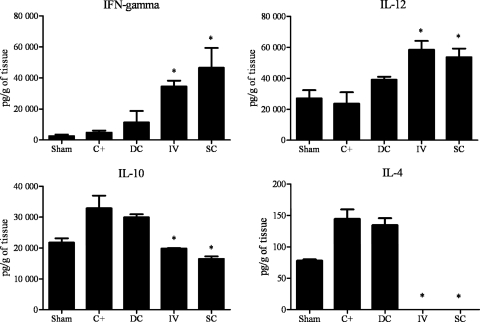

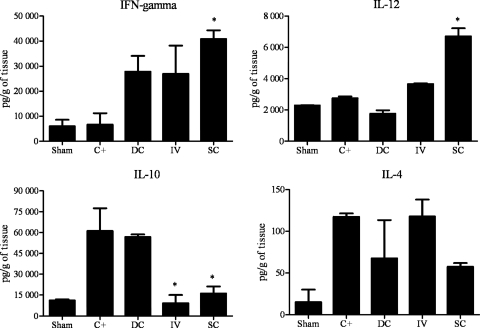

Cytokine pattern induced by immunization with P10-primed dendritic cells.

Cytokine levels were measured in the lung tissue of i.t. infected mice. As shown in Fig. 4, the therapeutic protocol groups that received P10-pulsed DCs via either the intravenous or subcutaneous route had significantly higher levels of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-12 and IFN-γ than the control groups. Additionally, the levels of IL-10 were significantly reduced in both P10-pulsed-DC-treated groups, and IL-4 was not detected.

Fig 4.

Cytokine detection: therapeutic protocol. Cytokines were assayed in the lung tissue from mice 45 days after i.t. infection. Each group (n = 5) was infected i.t. with 3 × 105 yeast cells. After 30 days, groups of mice received either unprimed dendritic cells (DCs) through subcutaneous route or P10-primed DCs via either an intravenous (IV) or subcutaneous (SC) route. A second identical immunization was administered 7 days later. The control group (C+) was not treated, and Sham represents uninfected and untreated mice. ∗, significant difference (P < 0.05) compared with C+ and DC groups.

As depicted in Fig. 5, the prophylactic protocol group that received P10-primed DCs subcutaneously had significantly increased levels of IL-12 and IFN-γ and reduced levels of IL-10. However, the group that received the vaccine intravenously did not show a significant increase of IL-12 or IFN-γ, but IL-10 was reduced. The IL-4 levels did not differ between groups subjected to the prophylactic protocol.

Fig 5.

Cytokine detection: prophylactic protocol. Cytokines were assayed in the lung tissue from mice 45 days after i.t. infection. The treatment groups (n = 5) of mice received either unprimed dendritic cells (DCs) through the subcutaneous (SC) route or P10-primed DCs via either an intravenous (i.v.) or subcutaneous route 24 h before the mice were infected i.t. with 3 × 105 yeast cells. The control (C+) group received PBS 1 day prior to infection, and Sham represents uninfected and untreated mice. ∗, significant difference (P < 0.05) compared with C+ and DC groups.

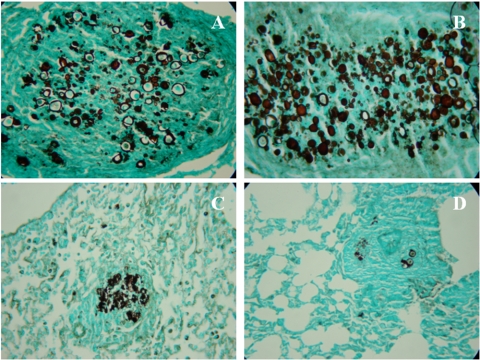

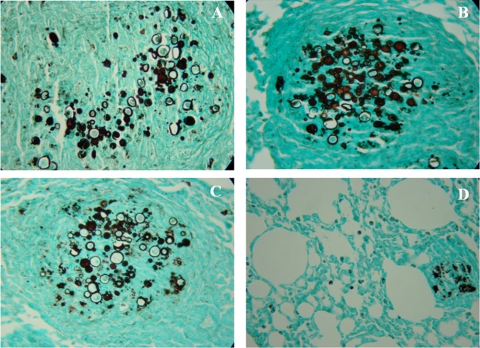

Lung histopathology in treated, i.t. infected BALB/c mice.

The lungs of the untreated control animals showed intense infiltrations of inflammatory cells with areas of proliferating fungal cells. In the therapeutic protocol, mice vaccinated with P10-primed DCs via intravenous or subcutaneous injection displayed significantly less lung tissue infiltration, few intact yeast cells, and large areas with preserved architecture (Fig. 6). In the prophylactic protocol, similar beneficial results were observed only in the group of animals that received P10-primed DCs by the subcutaneous route. The group prophylactically treated intravenously showed a pattern similar to that of the infected control mice (Fig. 7).

Fig 6.

Representative lung sections: therapeutic protocol. Histopathological sections of murine lungs 45 days after i.t. infection. (A) Representative section of lung from an infected and untreated mouse. For treatment, mice received at day 30 and 38 either unprimed DCs subcutaneously (B) or P10-primed DCs intravenously (C) or subcutaneously (D). Photographs of sections were taken at 400× magnification.

Fig 7.

Representative lung sections: prophylactic protocol. Representative histopathological sections of murine lungs 30 days after i.t. infection. Twenty-four hours prior to infection, mice received PBS (A), unprimed DCs subcutaneously (B), P10-primed DCs intravenously (C), or P10-primed DCs subcutaneously (D). Photographs of sections were taken at 400× magnification.

DISCUSSION

Current antimicrobial regimens for paracoccidioidomycosis require months to years of administration, carry risks for serious side effects, and result in frequent relapses (reviewed in reference 35). Peptide P10 induces strong, protective immunological responses, which makes it a lead candidate for a therapeutic vaccine against paracoccidioidomycosis. With or without adjunctive chemotherapy, P10 coadministered with adjuvant is highly effective at reducing the burden of P. brasiliensis from infected mice (24, 39).

DCs are potent stimulators of the immune response. Most importantly, they are capable of activating naive T cells by presenting peptide antigens and expressing high levels of costimulatory molecules (reviewed in reference 4). In the vaccine formulation used in this work, DCs were incubated with the peptide for 2 h, which provided sufficient time for the immature DCs to capture peptide antigens directly from the extracellular medium and rapidly display them for subsequent presentation to T lymphocytes (34). DCs can stimulate T cells at low concentrations of P10, and a single dendritic cell is able to activate 100 to 3,000 T cells (reviewed in reference 5). An additional benefit of DC vaccination is that adjuvants are not necessary.

The in vitro sensitized cell proliferation experiment showed that P10 at a concentration of 2.55 μM was not sufficient to induce splenocyte proliferation. However, coculture of splenocytes with DCs preincubated with 2.55 μM P10 resulted in significant splenoncyte proliferation. These results highlight the efficiency of DCs in antigen presentation and initiation of cellular response, with activation of sensitized or naive T cells (38).

In the present work, we examined the administration of P10-primed DCs via intravenous and subcutaneous routes. We studied the subcutaneous route, as previous reports show that injection of DCs into footpads resulted in the migration of significant numbers of these cells into draining lymph nodes within 24 h (3, 25). In our treatment protocols, we found that injection of primed DCs via either the intravenous or subcutaneous route in established PCM produced similar protective results, both in reducing fungal burden and stimulating a Th1-biased cytokine response. However, the route of vaccination was of critical importance when P10-primed DCs were administered prior to challenge with P. brasiliensis. Although subcutaneous vaccination led to lower pulmonary fungal burdens and Th1-biased cytokine responses, disease in mice that received intravenous vaccination with P10-primed DCs was similar to that in infected control animals. Hence, subcutaneously administered P10-primed DCs that migrated to draining lymph nodes were more effective in activating naïve T cells to elicit a Th1-biased response compared to DCs injected intravenously. The systemic injection of DCs results in their preferential distribution on the lungs, liver, and spleen (14, 17, 22, 30). The preferential migration of the intravenously injected DCs to the lungs prior to challenge with P. brasiliensis may result in tolerance to the targeted antigen and increasing susceptibility of the animal to subsequent infection, similar to what occurs with allergic sensitization (16). The effect is different in the presence of established P. brasiliensis disease. In this situation, the intravenously administered P10-primed DCs that rapidly migrated to the lung found an inflammatory environment ripe for regulation.

The cytokines assayed in this study were those that are related to the two major types of immune response in paracoccidioidomycosis. IFN-γ and IL-12 are representative of a Th1 response, which is protective against the fungal agent (2, 6, 7). In contrast, IL-4 and IL-10 are representative of a Th2 response, which aggravates the disease (2, 6). However, depending on the degree of inflammation caused by the Th1 response, the anti-inflammatory Th2 cytokines are essential to reach a balance with the Th1 cytokines in order to generate an appropriate protective immune response (42). The cytokine milieu achieved in infected mice after the intravenous or subcutaneous administration of P10-primed DCs demonstrated increased levels of Th1 cytokines with a concomitant decrease in Th2 cytokines. In contrast, only the subcutaneous administration of P10-primed DCs resulted in an increase in Th1 cytokines, and there was a mixed Th2 response, with only IL-10 decreasing. Histopathology of the mice that received P10-primed DCs intravenously or subcutaneously after infection was established or subcutaneously prior to challenge with P. brasiliensis revealed that the lungs of these mice had significantly lower numbers of epithelioid granulomas with reduced numbers of viable yeast cells, as confirmed by CFU studies, and large areas of preserved lung tissue. Although the intravenous administration of P10-primed DCs also reduced the concentrations of IL-4, it did not simulate increases in Th1 cytokines, and the fungal burdens and inflammatory changes in the lungs of these mice were similar to infected controls. These results reinforce the import of Th1 responses in protecting against progressive or severe paracoccidioidomycosis. In the therapeutic groups, the ratios of IFN-γ/IL-10 in the mice immunized with P10-primed DCs and challenged with P. brasiliensis were 3- to 5-fold higher than those immunized with unprimed DCs, clearly pointing to the induction of a Th1 response by the P10-primed DCs. This result confirms that a type-1 immune cellular response is the protective pattern in PCM.

In summary, the results show that P10-primed DCs can be protective when administered prior to challenge with P. brasiliensis and that the P10-primed DCs are therapeutic in the setting of established PCM. The effective vaccination routes induce strong Th1-biased responses. Since DCs may be more efficient than nonspecific commercial adjuvants, we propose that P10-primed DCs represent an important therapeutic to pursue for use in the prevention and treatment of paracoccidioidomycosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from FAPESP 2009/15823-7, 2010/51423-0, and CNPq 470513/2009-8.

C.P.T., S.R.A., and L.R.T. are research fellows of the CNPq.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 November 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Almeida SR, Lopes JD. 2001. The low efficiency of dendritic cells and macrophages from mice susceptible to Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in inducing a Th1 response. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 34: 529–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amaral AC, et al. 2010. Poly(lactic acid-glycolic acid) nanoparticles markedly improve immunological protection provided by peptide P10 against murine paracoccidioidomycosis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 159: 1126–1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Austyn JM. 2000. Antigen-presenting cells. Experimental and clinical studies of dendritic cells. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 162 (Part 2): S146–S150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Banchereau J, et al. 2000. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18: 767–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Banchereau J, Steinman RM. 1998. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392: 245–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Benard G. 2008. An overview of the immunopathology of human paracoccidioidomycosis. Mycopathologia 165: 209–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brummer E, Hanson LH, Restrepo A, Stevens DA. 1988. In vivo and in vitro activation of pulmonary macrophages by IFN-gamma for enhanced killing of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis or Blastomyces dermatitidis. J. Immunol. 140: 2786–2789 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buissa-Filho R, et al. 2008. The monoclonal antibody against the major diagnostic antigen of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis mediates immune protection in infected BALB/c mice challenged intratracheally with the fungus. Infect. Immun. 76: 3321–3328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cano LE, et al. 1998. Protective role of gamma interferon in experimental pulmonary paracoccidioidomycosis. Infect. Immun. 66: 800–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Castaneda E, Brummer E, Perlman AM, McEwen JG, Stevens DA. 1988. A culture medium for Paracoccidioides brasiliensis with high plating efficiency, and the effect of siderophores. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 26: 351–358 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cisalpino PS, et al. 1996. Cloning, characterization, and epitope expression of the major diagnostic antigen of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 4553–4560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Camargo ZP. 2008. Serology of paracoccidioidomycosis. Mycopathologia 165: 289–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dionne SO, et al. 2006. Spherules derived from Coccidioides posadasii promote human dendritic cell maturation and activation. Infect. Immun. 74: 2415–2422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eggert AA, et al. 1999. Biodistribution and vaccine efficiency of murine dendritic cells are dependent on the route of administration. Cancer Res. 59: 3340–3345 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gildea LA, Morris RE, Newman SL. 2001. Histoplasma capsulatum yeasts are phagocytosed via very late antigen-5, killed, and processed for antigen presentation by human dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 166: 1049–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holt PG, McMenamin C. 1989. Defense against allergic sensitization in the healthy lung: the role of inhalation tolerance. Clin. Exp. Allergy 19: 255–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huck SP, et al. 2008. Activation and route of administration both determine the ability of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells to accumulate in secondary lymphoid organs and prime CD8+ T cells against tumors. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 57: 63–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Inaba K, et al. 1992. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J. Exp. Med. 176: 1693–1702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Iwai LK, et al. 2003. In silico prediction of peptides binding to multiple HLA-DR molecules accurately identifies immunodominant epitopes from gp43 of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis frequently recognized in primary peripheral blood mononuclear cell responses from sensitized individuals. Mol. Med. 9: 209–219 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kurita N, Oarada M, Miyaji M, Ito E. 2000. Effect of cytokines on antifungal activity of human polymorphonuclear leucocytes against yeast cells of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. Med. Mycol. 38: 177–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kwon-Chung KJ, Tewari RP. 1987. Determination of viability of Histoplasma capsulatum yeast cells grown in vitro: comparison between dye and colony count methods. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 25: 107–114 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lappin MB, et al. 1999. Analysis of mouse dendritic cell migration in vivo upon subcutaneous and intravenous injection. Immunology 98: 181–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lutz MB, et al. 1999. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol. Methods 223: 77–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marques AF, et al. 2008. Additive effect of P10 immunization and chemotherapy in anergic mice challenged intratracheally with virulent yeasts of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. Microb. Infec. 10: 1251–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martin-Fontecha A, et al. 2003. Regulation of dendritic cell migration to the draining lymph node: impact on T lymphocyte traffic and priming. J. Exp. Med. 198: 615–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ministério da Saúde 2005. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Análise de Situação em Saúde. Saúde Brasil 2005: uma análise da situação de saúde no Brasil; Brasília (DF), Brazil [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ministério da Saúde 2009. Departamento de Informática do SUS—DATASUS. Arquivos eletrônicos dos dados do Sistema de Informações sobre Mortalidade—SIM. Base de dados 1996 a 2005. Brasília, Brazil: www.datasus.gov.br [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moscardi-Bacchi M, Brummer E, Stevens DA. 1994. Support of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis multiplication by human monocytes or macrophages: inhibition by activated phagocytes. J. Med. Microbiol. 40: 159–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mosmann T. 1983. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 65: 55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Okada N, et al. 2001. Administration route-dependent vaccine efficiency of murine dendritic cells pulsed with antigens. Br. J. Cancer 84: 1564–1570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Prado M, da Silva MB, Laurenti R, Travassos LR, Taborda CP. 2009. Mortality in Brazil of systemic mycosis as primary cause of death or in association with AIDS: a review from 1996 to 2006. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 104: 513–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Puccia R, McEwen JG, Cisalpino PS. 2008. Diversity in Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. The PbGP43 gene as a genetic marker. Mycopathologia 165: 275–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Puccia R, Schenkman S, Gorin PA, Travassos LR. 1986. Exocellular components of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis: identification of a specific antigen. Infect. Immun. 53: 199–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Santambrogio L, Sato AK, Fischer FR, Dorf ME, Stern LJ. 1999. Abundant empty class II MHC molecules on the surface of immature dendritic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96: 15050–15055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shikanai-Yasuda MA, Telles Filho Q, Mendes RP, Colomboand AL, Moretti ML. 2006. Guidelines in paracoccidioidomycosis. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 39: 297–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shortman K, Liu YJ. 2002. Mouse and human dendritic cell subtypes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2: 151–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shortman K, Lahoud MH, Caminschi I. 2009. Improving vaccines by targeting antigens to dendritic cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 41: 61–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Steinman RM, Witmer MD. 1978. Lymphoid dendritic cells are potent stimulators of the primary mixed leukocyte reaction in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 75: 5132–5136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Taborda CP, Juliano MA, Puccia R, Franco M, Travassos LR. 1998. Mapping of the T-cell epitope in the major 43-kilodalton glycoprotein of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis which induces a Th-1 response protective against fungal infection in BALB/c mice. Infect. Immun. 66: 786–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Teixeira MM, et al. 2009. Phylogenetic analysis reveals a high level of speciation in the Paracoccidioides genus. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 52: 273–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Travassos LR, Taborda CP, Iwai LK, Cunha Neto E, Puccia R. 2004. The gp43 from Paracoccidioides brasiliensis: a major diagnostic antigen and vaccine candidate, p 279–296 In Domer JE, Kobayashi GS. (ed), The Mycota XII human fungal pathogens. Springer-Verlag, Heildeberg, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 42. Travassos LR, Rodrigues EG, Iwai LK, Taborda CP. 2008. Attempts at a peptide vaccine against paracoccidioidomycosis, adjuvant to chemotherapy. Mycopathologia 165: 341–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Travassos LR, Goldman G, Taborda CP, Puccia R. 2007. Insights in Paracoccidioides brasiliensis pathogenicity, p 241–265 In Kavanagh K. (ed), New insights in medical mycology. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 44. Uenotsuchi TS, et al. 2006. Differential induction of Th1-prone immunity by human dendritic cells activated with Sporothrix schenckii of cutaneous and visceral origins to determine their different virulence. Int. Immunol. 18: 1637–1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]