Abstract

Summary: In the last 15 years, the genus Malassezia has been a topic of intense basic research on taxonomy, physiology, biochemistry, ecology, immunology, and metabolomics. Currently, the genus encompasses 14 species. The 1996 revision of the genus resulted in seven accepted taxa: M. furfur, M. pachydermatis, M. sympodialis, M. globosa, M. obtusa, M. restricta, and M. slooffiae. In the last decade, seven new taxa isolated from healthy and lesional human and animal skin have been accepted: M. dermatis, M. japonica, M. yamatoensis, M. nana, M. caprae, M. equina, and M. cuniculi. However, forthcoming multidisciplinary research is expected to show the etiopathological relationships between these new species and skin diseases. Hitherto, basic and clinical research has established etiological links between Malassezia yeasts, pityriasis versicolor, and sepsis of neonates and immunocompromised individuals. Their role in aggravating seborrheic dermatitis, dandruff, folliculitis, and onychomycosis, though often supported by histopathological evidence and favorable antifungal therapeutic outcomes, remains under investigation. A close association between skin and Malassezia IgE binding allergens in atopic eczema has been shown, while laboratory data support a role in psoriasis exacerbations. Finally, metabolomic research resulted in the proposal of a hypothesis on the contribution of Malassezia-synthesized aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligands to basal cell carcinoma through UV radiation-induced carcinogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Malassezia yeasts are unique under the view that they comprise almost exclusively the single eukaryotic member of the microbial flora of the skin. However, the complexity of the interaction of a unicellular eukaryotic organism (Malassezia) with a tissue of a multicellular organism (skin) makes understanding the interactions and development of disease a complex process. This is easily understood by the fact that once a revision of the genus Malassezia was described in a seminal publication by Guého et al. in 1996 (129), in addition to studying the epidemiology of this yeast in healthy and diseased skin, the need to repeat the already inconclusive experiments in relation to Malassezia immunology surfaced (14). Furthermore, the expansion of our knowledge on the complex homeostatic mechanisms of the skin increases the candidate targets of interactions between this yeast and skin cells.

In this article, in addition to reviewing the taxonomy and identification methods for the currently accepted Malassezia species, an effort is also made to critically assess the available data on Malassezia epidemiology and nosology in humans and the existence of pathogenic subtypes within Malassezia species, their biological characteristics, and their relevance to skin disease. Therapeutic approaches for the treatment of pityriasis versicolor, the prototypical Malassezia-associated skin disease, will be briefly discussed. Furthermore, data on Malassezia systemic infections are reviewed, and provisional diagnostic criteria are proposed.

TAXONOMY AND IDENTIFICATION METHODS

An overview of the historical events underlying Malassezia taxonomy may be considered prima facie avoidable in the era of metagenomics. To reduce biased interpretations of taxonomic issues, it was deemed essential to refer to the succession of scientific inquiries that in the last 20 years brought about scrupulous research on diverse domains covering Malassezia biology. In many respects, the series of events preceding the current taxonomic status account for the numerous, independently derived theories regarding the role of Malassezia as a skin commensal and pathogen.

Current taxonomy places Malassezia (Baillon) yeasts (19) in the Phylum Basidiomycota, subphylum Ustilaginomycotina, class Exobasidiomycetes, order Malasseziales, and family Malasseziaceae. Today, the genus Malassezia includes 14 lipophilic species that have been isolated from healthy and diseased human and animal skin. However, Malassezia yeasts have been recognized for more than 150 years (91) as members of the human cutaneous flora and etiologic agents of certain skin diseases. As early as the early 1800s, it was noted that yeast cells and filaments were present in the skin scales of patients with pityriasis versicolor (267), whereas yeast cells, but no filaments, were observed in scales from healthy scalp, seborrheic dermatitis scalp, and dandruff. The absence of filaments in seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff lesional scales for many years led to uncertainty regarding the placement of yeast isolates from pityriasis versicolor and those from seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff into the same genus (32, 208, 274). Eventually, Sabouraud (274) placed them into separate genera and named the yeasts forming filaments in pityriasis versicolor skin scales Malassezia furfur and those which did not form filaments in dandruff and seborrheic dermatitis skin scales Pityrosporum malassezii. Almost a decade later, Pityrosporum malassezii was allotted the binomial nomenclature Pityrosporum ovale by Castellani and Chalmers (50) Subsequently, the lipid dependence of the growth of these yeasts was established (127), and it was confirmed that Pityrosporum orbiculare and P. ovale are variants of the same species (97).

From a historical standpoint, it is interesting that isolates from exfoliative dermatitis of a rhinoceros described by Weidman in 1925 (332) and from otitis externa of dogs described by Gustafsson in 1955 (139), although given the names Pityrosporum pachydermatis and Pityrosporum canis, respectively, were in due course found to have similar morphologies. As both isolates did not require lipid supplements for growth in culture, P. canis was accepted as a synonym for P. pachydermatis. Therefore, since 1970, and for approximately 14 years, it was acknowledged that the genus Pityrosporum included three species: P. ovale, P. orbiculare, and P. pachydermatis (292). During that time, the morphological similarities between Pityrosporum and Malassezia, as described by Eichstedt (91) and by Panja (240), were assessed. Hence, in the early 1980s, a reevaluation of those previous studies instigated among taxonomists an unequivocal acceptance of the genus name Malassezia over that of the genus name Pityrosporum. This was based on the morphology, ultrastructure (25, 246), and immunological properties (293, 310) of Malassezia yeasts. In addition, (i) microscopic observations of hyphae in skin scales from pityriasis versicolor lesions and (ii) confirmation of hyphal production by P. orbiculare clinical isolates in culture (87, 233) confirmed its placement in the genus Malassezia. Hence, within the genus Malassezia, the species M. furfur integrated both lipid-dependent yeasts, formerly referred to as P. orbiculare and P. ovale (342). However, toward the end of the 1980s, further studies demonstrated the existence of several M. furfur serovars (69, 221), providing evidence of diversity within the genus, which was observed in vivo as well as in vitro. Following pioneering work based on studies of nuclear DNA G+C content and a DNA-DNA hybridization technique, a new species, Malassezia sympodialis, was defined (290). Eventually, the genus Malassezia was revised and enlarged in 1996 to include 7 species (129). In a description of the new species by Guého et al. (129), conventional and modern spectrum techniques were employed, encompassing morphology, ultrastructure, physiology, and molecular biology. As a result, the genus included seven species, the three former taxa M. furfur, M. pachydermatis, and M. sympodialis and four new taxa, M. globosa, M. obtusa, M. restricta, and M. slooffiae. Lipid dependence for growth remained a common feature among all species, with the exception of M. pachydermatis, and molecular data were in accordance with phenotypic properties, which differed among species. These properties included differential per-species abilities to utilize lipid supplements, catalase and beta-glucosidase reactions, and temperature tolerance at 32°C, 37°C, and 40°C, thus providing a phenotypic identification algorithm for the routine identification of Malassezia isolates to the species level (Table 1). Despite the undisputable value of phenotypic identification, ambiguous results have been reported (132). For example, an accurate differentiation among M. furfur, M. sympodialis, and M. slooffiae isolates is often hindered because results from physiological tests on the basis of Tween compound utilization are very similar (Table 1).

Table 1.

Routine phenotypic characterization of 14 Malassezia species based on their identifiable physiological and biochemical propertiesa

| Malassezia species | Presence of growth on: |

Test result |

Reference | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDA at 32°C | mDA |

Tween utilization |

Cremophor EL utilization | β-Glucosidase | Catalase | |||||||

| 32°C | 37°C | 40°C | Tween 20 | Tween 40 | Tween 60 | Tween 80 | ||||||

| M. furfur | − | + | + | + | +/IGP | +/IGP | +/IGP | +/IGP | +/− IGP | +/− IGP | +/− IGP | 129 |

| M. sympodialis | − | + | + | + | −/± | + | + | + | −/± | + | + | 129 |

| M. globosa | − | + | −/± | − | − | −/IGP | −/IGP | − | − | − | + | 129 |

| M. restricta | − | + | v | − | − | −/IGP | −/IGP | − | − | − | − | 129 |

| M. obtusa | − | + | −/± | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | 129 |

| M. slooffiae | − | + | + | + | +/± | + | + | −/± | − | − | + | 129 |

| M. dermatis | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/± | +/± | NE | + | 288 |

| M. japonica | − | + | + | − | − | ± | + | − | NE | NE | + | 287 |

| M. nana | − | + | + | v | v | + | + | ± | − | − | + | 147 |

| M. yamatoensis | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | NE | NE | + | 285 |

| M. equina | − | + | ± | − | ± | + | +/IGP | +/IGP | − | − | + | 38 |

| M. caprae | − | + | −/± | − | −/IGP | +/IGP | +/IGP | +/− IGP | − | +/− IGP | + | 38 |

| M. cuniculi | − | +/± | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | 39 |

| M. pachydermatis | +/± | + | + | + | +/IGP | + | + | + | +/IGP | +/− IGP | +/± | 129 |

SDA, Sabouraud dextrose agar (also referred to as glucose peptone agar [GPA] by several authors; mDA, modified Dixon's agar; SDA, Dixon's agar supplemented with water-soluble lipids, such as Tweens and Cremophor EL, to identify lipophilic and lipid-dependent Malassezia species; ±, weak growth; v, variable; IGP, inconsistent growth pattern (rarely observed); NE, not evaluated (in the description of this species).

Undoubtedly, since the mid-1990s, molecular techniques, and in particular rRNA sequencing analysis (131), advanced Malassezia systematics, linked molecular systematics to the circumscription of new species, and warranted nonculture detection and identification of Malassezia species in patient skin scales from a variety of Malassezia-associated or -exacerbated diseases (114, 119, 295). This also accelerated developments in PCR-based identification methods (Table 2), promoted investigation into Malassezia epidemiology (64, 112) and pathobiology (108), and encouraged research on the association of certain Malassezia species with specific geographical locations (136).

Table 2.

Identification of Malassezia species from pure culture by sequencing and/or PCR-based methodsa

| PCR-based method and genomic region | Origin(s) of strains and Malassezia species | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| ITS amplification and sequencing | Culture collection strain of M. furfur; clinical isolates of M. pachydermatis, M. restricta, M. dermatis, M. caprae, M. equina, M. cuniculi | 39, 40, 194, 256, 257, 303 |

| ITS amplification, REA, and sequencing and ITS and REA only | Type, neotype, culture collection strains, and clinical isolates of M. furfur, M. obtusa, M. globosa, M. slooffiae, M. sympodialis, M. restricta, M. pachydermatis, M. dermatis, M. japonica, M. nana, M. yamatoensis | 111, 114, 286 |

| 26S rRNA gene (LSU) amplification and REA and 26S rRNA gene (LSU) amplification and sequencing | Clinical isolates of M. furfur, M. obtusa, M. globosa, M. slooffiae, M. sympodialis, M. restricta, M. pachydermatis, M. dermatis, M. caprae, M. equina, M. cuniculi M. japonica, M. nana, M. yamatoensis | 39, 40, 47, 130, 137, 164, 223, 238 |

| DNA microcoding array (Luminex xMAP platform) | M. furfur, M. obtusa, M. globosa, M. slooffiae, M. sympodialis, M. restricta, M. pachydermatis, M. dermatis, M. japonica, M. nana, M. yamatoensis, M. equina | 82 |

ITS, internal transcribed spacer (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2) of the ribosomal DNA region; REA, restriction enzyme analysis; LSU, large subunit.

In addition, molecular systematics had an impact on the recognition of new Malassezia species associated with human and animal disease. By 2004, three more new species were described: Malassezia dermatis and M. japonica, isolated from Japanese atopic dermatitis (synonym, atopic eczema) patients (299, 300), followed by M. yamatoensis, isolated from healthy human skin and from a patient with seborrheic dermatitis (297). New lipid-dependent species, such as M. nana (150), M. caprae, M. equina (39), and, recently, M. cuniculi (40), from animal skin were also described, raising the number of currently recognized Malassezia species to 14.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Culture-Based Epidemiology

More than 20 studies (Tables 3 to 6) have been carried out worldwide on the epidemiology of Malassezia species in cases of pityriasis versicolor, seborrheic dermatitis, atopic eczema, and psoriasis and on healthy control skin of the same individuals or skin from healthy volunteers (53, 63, 89, 112, 122, 146, 171, 173, 180, 185, 228, 237, 255, 259, 275, 286, 344, 353). Results are not directly comparable between studies, as different methodologies, isolation media, and identification procedures have been employed. However, these results can be used for the extraction of interesting conclusions on the epidemiology and pathobiology of Malassezia species. Furthermore, it should be noted that in all those studies, the surface of the skin was sampled and not the hair infundibulum, which is the niche of Malassezia yeasts. From the available data (Tables 3 to 6), we can conclude that the 7 Malassezia species described in 1996 (68) are the most common ones, while geographical variations in species distribution are apparent. M. dermatis has been isolated in East Asia (Japan and South Korea), while M. obtusa has been isolated mostly in Sweden, Canada, Bosnia, and Herzegovina but has also been reported in Iran and Indonesia. Identification and typing of the latter isolates with molecular techniques might reveal the existence of atypical M. obtusa-M. furfur subtypes, as these two species are phylogenetically close, and M. furfur shows considerable diversity (106, 315).

Table 3.

Results from culture-based epidemiological studies of healthy skin

| Reference | No. of patients/no. of positive cultures | % of cultures positive for: |

Culture mediuma | Location(s) | Description | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. globosa | M. restricta | M. sympodialis | M. furfur | M. slooffiae | M. obtusa | M. dermatis | |||||

| 353 | 123/107 | 78 | 1 | 7 | 21 | LNA | Iran | 7% mixed species (>2 species isolated); percentages correspond to avg of 3 samplings/patient | |||

| 238 | 60/38 | 28 | 32 | 29 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | LNA | South Korea | Variations in isolation of species according to age; variation, yet not significant, in isolation of species according to body part; M. restricta on the forehead, M. sympodialis and M. globosa on the chest |

| 164 | 160/599 (960 samples) | 22 | 22 | 12 | 4.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | LNA | South Korea | M. globosa and M. restricta were found more commonly in different age groups; M. restricta and M. globosa were found more commonly on the scalp; M. globosa and M. sympodialis were found more commonly on the trunk; mixed species were commonly isolated |

| 254 | 40/32 | 40 | 20 | 17.5 | 2.5 | mDA | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Healthy trunk skin of seborrheic dermatitis patients | |||

| 255 | 90/82 | 49 | 37 | 5.5 | mDA | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Healthy trunk skin of pityriasis versicolor patients, away from lesions; no association of the isolated species with sex, age, clinical appearance of pityriasis versicolor (hyper- or hypopigmented), duration of disease | ||||

| 135 | 245/172 | 32 | 1 | 57 | 6 | 3 | LNA | Canada | Differences in isolation rates of species between age groups and body locations were recorded; no mixed species isolated | ||

| 138 | 20/19 | 28 | 6 | 47 | 11 | 7.5 | LNA | Canada | CFU was equivalent to that associated with pityriasis versicolor and significantly more than those for psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and atopic eczema | ||

| 195 | 120 (600 samplings)/393 | 41 | 49 | 6 | 4 | 2 | LNA | South Korea | M. restricta was more common on the forehead and in younger age groups (<50 yr old); M. globosa was more frequent in patients aged >50 yr | ||

| 311 | 100/60 | 42 | 3 | 25 | 23 | 7 | DA | Iran | |||

| 277 | 31/26 | 12 | 69 | 4 | 15 | LNA | Sweden | Mixed species were cultured in 11% of patients; healthy skin and seborrheic dermatitis skin were significantly more colonized than atopic eczema skin | |||

| 228 | 105/52 | 42 | 2 | 21 | 6 | 2 | DA | Japan | Two groups of healthy volunteers, i.e., 35 random volunteers and 73 medical school students; M. globosa, M. furfur, and M. sympodialis were isolated more frequently from scalp and face, but there was a low recovery rate for both groups studied; M. globosa and M. sympodialis were isolated from the trunks of healthy volunteers | ||

| 275 | 35/11 | 49 | 8 | 23 | 20.5 | 2 | mDA | Tunis | 3 sampling sites per patient, more than 1 isolate per patient; frequency of M. globosa on pityriasis versicolor skin was significantly higher than that on healthy skin | ||

| 171 | 58/37 | 19 | 50 | CHROMagar Malassezia | Japan | Sampling of the external ear canal was performed; M. slooffiae was characterized as a specific isolate with increasing prevalence after the age of 30 yr | |||||

NA, Leeming-Notman agar; mDA, modified Dixon's agar; DA, Dixon's agar.

Table 6.

Results from culture-based epidemiological studies of atopic eczema and psoriasis

| Skin condition and reference | No. of patients/no. of positive cultures | % of cultures positive for: |

Culture mediuma | Location | Description | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. globosa | M. restricta | M. sympodialis | M. furfur | M. slooffiae | M. obtusa | M. dermatis | |||||

| Atopic eczema | |||||||||||

| 138 | 31/22 | 18 | 8 | 51 | 10 | 3 | 10 | LNA | Canada | No. of CFU from cases of atopic eczema was significantly lower than that from healthy or pityriasis versicolor skin | |

| 344 | 60/31 | 16 | 22 | 32 | 21 | 3 | 6.5 | LNA | South Korea | Trend in the severity of atopic eczema with Malassezia colonization was observed | |

| 277 | 124/69 | 28 | 3 | 46 | 4 | 7 | 30 | LNA | Sweden | Mixed species were cultured in 11% of patients; healthy skin and seborrheic dermatitis skin were significantly more colonized than atopic eczema skin; M. globosa was significantly more common in atopic eczema skin | |

| Psoriasis | |||||||||||

| 353 | 110/69 | 45 | 11 | 11 | 38 | LNA | Iran | 9% of patients had mixed cultures (>2 species); significant differences in isolation rates from psoriatic skin and healthy skin on the head | |||

| 138 | 28/19 | 58 | 31 | 11.5 | LNA | Canada | No. of CFU in psoriasis skin was significantly lower than those for other Malassezia-associated dermatoses; Malassezia grew more commonly on scalp and face than on arms and legs | ||||

LNA, Leeming-Notman agar.

Table 4.

Results from culture-based epidemiological studies of pityriasis versicolor lesions

| Reference | No. of patients/no. of positive cultures | % of cultures positive for: |

Culture mediuma | Location(s) | Description | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. globosa | M. restricta | M. sympodialis | M. furfur | M. slooffiae | M. obtusa | M. dermatis | M. pachydermatis | |||||

| 63 | 96/93 | 97 | 33 | 7 | mDA | Spain | M. sympodialis and M. slooffiae were coisolated with M. globosa in 36.5% of patients; no association of Malassezia species with clinical form, pityriasis versicolor episode, or severity | |||||

| 138 | 23/21 | 18 | 63 | 8 | 8 | 4 | LNA | Canada | CFU from pityriasis versicolor skin was equivalent to that from healthy skin and significantly more than that from psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and atopic eczema skin | |||

| 136 | 129 | 25 | 59.5 | 11 | 4 | 2 | LNA | Canada | 1 colony per culture was processed for identification; no species was particularly associated with body site | |||

| 188 | 100/87 | 56.5 | 2 | 10 | 25 | 1 | mDA | Tunis | 18 mixed cultures of M. globosa with M. sympodialis or M. furfur | |||

| 180 | 70/48 | 40 | 2 | 58 | mDA | India | Only direct-microscopy specimens were cultured; no mixed cultures identified | |||||

| 53 | 90/87 | 57.5 | 3 | 15 | 1 | 1 | mDA | India | No difference in isolation rates of species in patients ≤20 or >20 yr old as well as between genders | |||

| 259 | 166/116 | 44 | 9 | 30 | 7 | 10.5 | mDA | Iran | Prevalence of Malassezia species varied according to age, gender, and anatomic location | |||

| 286 | 69/61 | 48 | 2 | 8 | 41 | LNA | Iran (Northern) | No correlation between Malassezia species and body site sampled or age | ||||

| 311 | 94/75 | 53 | 9 | 25 | 4 | 8 | DAk | Iran | No difference in distribution of species between healthy and pityriasis versicolor skin | |||

| 255 | 90/90 | 63 | 14 | 10 | 4 | 8 | mDA | Bosnia and Herzegovina | No mixed cultures observed; upon direct microscopy of pityriasis versicolor scales, evidence of mixed species was found in 37% of isolates; no association of species and clinical appearance of lesions | |||

| 112 | 76/71 | 77 | 2 | 13 | 5 | 3 | mDA | Greece | M. globosa was isolated in 90% of cases in association with one of the other species | |||

| 122 | 218/239 | 38 | 1 | 37 | 21 | 2 | 0.5 | mDA | Argentina | In 15/218 patients, 2 species were coisolated, and in 3/218 patients, 3 species were coisolated; percentages refer to isolates and not patients | ||

| 89 | 427/250 | 64 | 5 | 34 | mDA | India | 23/250 patients had mixed cultures with M. globosa | |||||

| 185 | 98/91 | 14 | 1 | 27.5 | 34 | 10 | 6 | LNA | Indonesia | Without reaching statistical significance in the isolation rate, M. furfur was not found in patients with duration of disease of <1 mo; no difference in distribution of species and age or gender | ||

| 173 | 97/44 | 48 | 36 | 16 | mDA | Turkey | Mixed species were not isolated; statistical differences in species distribution and duration of disease, sun-exposed or sun-protected lesions, hypo- or hypepigmented skin | |||||

mDA, modified Dixon's agar; LNA, Leeming-Notman agar; DA, Dixon's agar.

Table 5.

Results from culture-based epidemiological studies of seborrheic dermatitis

| Reference | No. of patients/no. of positive cultures | % of cultures positive for: |

Culture mediuma | Location(s) | Description | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. globosa | M. restricta | M. sympodialis | M. furfur | M. slooffiae | M. obtusa | M. dermatis | M. japonica | |||||

| 138 | 28/23 | 45 | 37.5 | 7.5 | 10 | 8 | LNA | Canada | Patients in this group had higher CFU counts in healthy than in diseased skin | |||

| 238 | 60/31 | 22.5 | 38 | 28 | 9 | 3 | LNA | South Korea | Variations in isolation of species according to age; variation, yet not significant, in isolation of species according to body part; M. restricta on forehead, M. sympodialis and M. globosa on chest | |||

| 146 | 100/77 | 56 | 9 | 1 | 32.5 | 1 | LNA | Iran | M. globosa was more commonly isolated from face, M. furfur was more commonly isolated from trunk | |||

| 277 | 16/14 | 36 | 43 | 7 | 14 | 43 | LNA | Sweden | Mixed species were cultured in 11% of patients; healthy skin and seborrheic dermatitis skin were significantly more colonized than atopic eczema skin | |||

| 112 | 45/38 | 58 | 48 | 8 | 2 | 5 | mDA | Greece | Strains of less common species were coisolated with M. globosa and M. restricta | |||

| 228 | 42 | 21 | 6 | 21 | DA | Japan | No difference in isolation rate of M. globosa and M. furfur from lesional and nonlesional skin, but these two species were significantly more common than in skin of healthy subjects | |||||

| 254 | 40/35 | 17.5 | 27.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 15 | mDA | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2.5% of patients had M. pachydermatis on lesional skin; isolation from scalp/face was performed | |||

LNA, Leeming-Notman agar; mDA, modified Dixon's agar; DA, Dixon's agar.

Non-Culture-Based Epidemiology

Interesting results have been obtained from studies of Malassezia population dynamics in healthy or diseased human skin employing techniques that directly identify and quantify Malassezia DNA from skin specimens (Table 7). No substantial difference was found in the distributions of Malassezia species subtypes identified in the left and right halves of the body skin of healthy volunteers and psoriasis patients (243, 244). Also, there was no significant difference in the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequences of the strains colonizing healthy and psoriasis skin (243, 244). The predominant species in non-culture-based epidemiological studies are M. globosa and M. restricta, which are found on the skin of practically all humans. However, this introduces ambiguity regarding their pathogenic potential, as they are found on healthy and diseased skin equally, thus not fulfilling Koch's postulates. For this reason, the use of robust typing methods, such as multilocus sequencing typing, for the screening of pathogenic versus nonpathogenic Malassezia strains would highlight the pathobiology of Malassezia yeasts.

Table 7.

Epidemiological data for non-culture-based methods

| Skin type and reference | No. of patients | % of cultures positive for: |

Method(s) and target gene(s)a | Description | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. globosa | M. restricta | M. sympodialis | M. furfur | M. slooffiae | M. obtusa | M. dermatis | M. yamatoensis | M. japonica | ||||

| Healthy | ||||||||||||

| 308 | 20 | 100 | 92 | Quantitative PCR targeting 26S rDNA and the ITS2 region | Healthy skin of psoriasis patients; only M. globosa and M. restricta were searched for | |||||||

| 307 | 27 | 70 | 56 | 15 | 22 | 18.5 | 4 | 4 | Nested PCR, real-time PCR targeting ITS1 and IGS1 regions | Healthy skin of seborrheic dermatitis patients | ||

| 307 | 30 | 87 | 83 | 37 | 27 | 17 | 10 | 30 | 7 | 10 | Nested PCR, real-time PCR targeting ITS1 and IGS1 regions | Healthy patients |

| 295 | 18 | 44.5 | 61 | 50 | 11 | 7 | Nested PCR targeting ITS1, ITS2, 5.5S rDNA | Healthy university students | ||||

| Pityriasis versicolor | ||||||||||||

| 224 | 49 | 94 | 94 | 35 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 24.5 | 4 | 6 | Nested PCR, real-time PCR targeting ITS1 and IGS1 regions | Only M. globosa was detected in scales with hyphae by direct microscopy |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | ||||||||||||

| 307 | 31 | 93.5 | 74 | 35.5 | 6.5 | 39 | 10 | 39 | 10 | 13 | Nested PCR, real-time PCR targeting ITS1 and IGS1 regions | Lesional seborrheic dermatitis skin harbored 3 times more Malassezia populations than healthy skin |

| Atopic eczema | ||||||||||||

| 344 | 60 | 16 | 22 | 32 | 21 | 3 | 6 | PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism, 26S rDNA | Mixed isolations were observed but not further analyzed; there was no significant difference between positive Malassezia cultures, isolated Malassezia species, and severity of atopic eczema | |||

| 307 | 36 | 100 | 97 | 58 | 33 | 31 | 28 | 31 | 14 | 58 | Nested PCR, real-time PCR targeting ITS1 and IGS1 regions | Atopic eczema skin was colonized more often than seborrheic dermatitis, pityriasis versicolor, or healthy skin |

| 295 | 32 | 87.5 | 94 | 41 | 41 | Nested PCR targeting ITS1, ITS2, 5.8S rDNA | M. restricta, M. globosa, and M. furfur DNAs were more commonly found in atopic eczema lesions than in controls; this was not found for M. sympodialis | |||||

| 298 | 34 | 30–35 | 45–51 | qPCR targeting 26S rDNA and the ITS2 region | Only M. globosa and M. restricta were searched for; Malassezia colonized all atopic eczema patients, but the load on the head was 12.4 times higher than that on the trunk and 6.8 times higher than that on limbs | |||||||

| Psoriasis | ||||||||||||

| 308 | 20 | 98 | 92 | No correlation of psoriasis severity with Malassezia colonization; Malassezia load on the head was 10-40 times higher than that on the trunk; M. restricta was significantly more common than M. globosa in lesional skin of the head and limb; the other Malassezia species were not individually searched for | ||||||||

| 9 | 22 | 82 | 96 | 64 | 18 | 27 | 18 | 27 | 14 | 27 | IGS, ITS | No difference in detection rate of Malassezia spp. between healthy and psoriasis skin and no associations with age, gender, site, severity, or treatment; psoriasis and atopic eczema skin presented higher levels of species variability |

ITS, internal transcribed spacer; IGS, intergenic spacer.

Molecular typing of Malassezia yeasts.

Current data (Table 8) point toward the existence of pathogenic subtypes of M. furfur (113, 170, 350), M. globosa (112, 307), and M. restricta (296, 307). The Malassezia microbiota was suggested to be host specific (243). Moreover, for M. furfur, phylogeographic associations have also been found in Greek, Swedish, and Bulgarian strains (106) as well as in the Han and Tibetan ethnic groups in China (350). M. sympodialis seems to represent a homogenous species, with no pathogenic subtypes detected by current molecular methods. However, our current molecular typing approaches are limited, as they provide only indirect evidence on virulence. In that respect, neither the observed sequence variation within the rDNA complex nor the polymorphism determined by PCR-based methods (Table 8) accounts for actual virulence. Essentially, these methods depict disease-associated subtypes that could represent pathogenic lineages whose survival is favored on diseased skin under conditions which are presently inadequately understood.

Table 8.

Malassezia species subtypes associated with skin diseasesa

| Malassezia sp. and reference | Method | Description |

|---|---|---|

| M. globosa | ||

| 112 | PCR–single-strand conformational polymorphism of ITS1 | M. globosa strains were distinguished into 5 subtypes; 1 was associated with extensive disease |

| 307 | IGS1 sequencing | 8 groups were identified, 1 comprised of healthy strains, 5 comprised of seborrheic dermatitis and atopic eczema, and 2 comprised of healthy and seborrheic dermatitis strains |

| 294 | IGS1 sequencing | 4 groups, 2 from atopic eczema, 1 healthy, and 1 healthy and atopic eczema mixed |

| M. restricta | ||

| 296 | IGS1 sequencing | Strains from healthy individuals were distinguished from strains from atopic eczema patients and had fewer sequence repeats |

| 307 | IGS1 sequencing | A healthy skin group and a seborrheic dermatitis group were identified |

| 247 | Sequencing of 18S rDNA (partial), ITS1, 5.8S rDNA, ITS2, and 28S rDNA (partial) | Six sequence types were identified in building dust, and Malassezia yeasts were the most common isolates, especially in winter |

| M. sympodialis | ||

| 112 | PCR–single-strand conformational polymorphism of ITS1 | M. sympodialis displayed a uniform profile |

| 109 | PCR–single-strand conformational polymorphism of Mala s 1 sequences | M. sympodialis displayed a uniform profiles |

| 38 | Sequencing of D1 and D2 regions of 26S rDNA, ITS-5.8 rDNA | Isolates from different animals clustered within 4 groups, including M dermatis and M. nana |

| 207 | ITS1 sequencing | Subgroups in stock strains identified without clinical relevance |

| 134 | Amplified fragment length polymorphism | M. sympodialis displayed uniform profiles |

| M. furfur | ||

| 111 | PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism of ITS2 | M. furfur strains of Greek origin presented an additional BanI restriction site compared to Bulgarian and CBS collection strains |

| 125 | 26S D1/D2 sequencing, partial 5.8S and ITS2 region sequencing | Colombian M. furfur isolates with variable Tween assimilation profiles clustered into a distinct group |

| 207 | ITS1 sequencing | Subgroups in stock strains identified without clinical relevance |

| 315 | Amplified fragment length polymorphism | 4 subgroups identified; 1 included systemic isolates from humans |

| 117 | PCR-random amplified polymorphic DNA | Pityriasis versicolor strains were differentiated from seborrheic dermatitis/seborrheic dermatitis-HIV strains |

| 134 | Amplified fragment length polymorphism | Strains from neonatal systemic infections and skin clustered into two distinct groups |

| 350 | PCR-fingerprinting (M13 primer) | M. furfur from Han and Tibetan volunteers clustered into different groups; also, skin disease associations were evident |

| 88 | PCR-random amplified polymorphic DNA (M13, OPA2, OPA4) | Only 5 strains of M. furfur were included, and some difference could be observed between human and cattle isolates |

| 113 | PCR-fingerprinting (M13 primer) | Greek, Bulgarian, and Scandinavian (permanent Greek residents) strains were categorized into distinct groups; within the Bulgarian cluster, seborrheic dermatitis strains were differentiated from pityriasis versicolor and dandruff strains |

| 170 | ITS1 sequencing | All isolates from blood culture bottles and catheter tips clustered into a single group |

| M. slooffiae | ||

| 88 | PCR-random amplified polymorphic DNA (M13, OPA2, OPA4 primers) | OPA2 and OPA4 differentiated human from cattle isolates |

| M. pachydermatis | ||

| 207 | ITS1 sequencing | Subgroups in stock strains identified without clinical relevance |

| 3 | chs-2 sequencing, PCR-random amplified polymorphic DNA (FM1 primer) | Four subgroups were differentiated; good correlation between the 2 methods |

| 46 | LSU rDNA, ITS1, chs-2 gene sequencing | 3 major groups with lipid-dependent strains clustering in 2 of them, and non-lipid-dependent strains dispersed in all 3 groups; associations with origins of strains were highlighted |

| 45 | PCR–single-strand conformational polymorphism of the ITS1 region and chs-2 | Typing was possible without any clinically relevant information retrieved |

| 43 | PCR–single-strand conformational polymorphism of the ITS1 region and chs-2 | ITS1 region more variable than chs-2 sequences; 3 major genotype groups distinguished, and 2 were associated with extensive disease and increased phospholipase activity, and 1 was associated with healthy skin and lower phospholipase activity |

| 222 | Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis | Considerable genetic variation corresponding to that revealed by partial LSU sequencing |

| 4 | PCR-random amplified polymorphic DNA (FM1 primer), chs-2 sequencing | Low discriminatory potential due to the same origin of the strains (dog otitis) |

| 49 | PCR-random amplified polymorphic DNA (M13, OPT-20) | M13 primer did not differentiate groups; OPT-20 differentiated 4 groups, with 2 of them correlating with the external ear canal of dogs |

ITS, internal transcribed spacer; IGS, intergenic spacer; LSU, large subunit; chs-2, chitin synthase 2 gene.

Conclusion

In the ongoing debate on the usefulness of conventional epidemiological studies on the distribution of Malassezia species, it should be noted that more accurate epidemiological data on species distribution can be acquired by non-culture-based molecular techniques. However, conventional culture and identification methods offer the advantage of further evaluating the isolates for possible virulence factors, such as the production of phospholipase (44, 170) and indole (108, 184, 336) and melanin synthesis (107). Furthermore, this was highlighted in a study by Akaza et al. (6), in which the seasonal rates of isolation of Malassezia species from healthy skin determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) were compared with those determined by use of Leeming-Notman agar (197). Increased Malassezia colonization of the skin in summer was determined by culture but not by PCR. This finding can be attributed to the ability of culture to select viable cells, while PCR also quantifies DNA from nonviable or not metabolically active cells. Furthermore, the initial optimism on the pathogenic potential of M. globosa and its characterization as the causative agent of pityriasis versicolor (63) was subsequently weakened by findings supporting the widespread distribution of this species on healthy skin as well as in seborrheic dermatitis, atopic eczema, and psoriasis skin lesions (Tables 3 to 6). The matter is further complicated by the lower rate of recovery of Malassezia yeasts from lesional skin in the latter three skin diseases than from healthy skin, which points toward the existence of metagenomic alterations in the pathogenic strains of Malassezia species in order to survive in the altered environment of diseased skin.

MALASSEZIA INTERACTION WITH EPIDERMAL AND IMMUNE CELLS

Gradually, experimental data on the multiple facets of the interaction of Malassezia yeasts with different cell types are being collected. Although safe conclusions cannot be drawn, this area of research remains a promising field.

Experimental Data

Malassezia yeasts demonstrate a species-specific ability to interact with cells that are constitutive members of the skin and its adnexal structures, such as various keratinocyte subpopulations, or cell lineages that are involved in immune functions, including antigen-presenting dendritic cells, macrophages, eosinophils, and neutrophils (Table 9). The exposure of the above-mentioned cells to Malassezia yeasts or their products has been shown to induce the production of a variety of cytokines; however, the results are not directly comparable, as different cell lines and protocols have been employed (Table 9). The effect of Malassezia yeasts on cytokine production from keratinocytes in vitro depends on the culture phase of the yeast (stationary versus exponential), on the Malassezia species used, and on the previous manipulations (removal or not) of the yeast cell lipid layer (316). However, this does not universally apply to all the immune response-regulating molecular pathways that operate in epidermal keratinocytes, as it was recently shown that M. globosa and M. restricta could equally efficiently stimulate lysophosphatidic acid receptors in these cells and increase the production of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (160). This property was abrogated when the lipid layer was removed from Malassezia cells. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin may participate in the pathogenesis of atopic eczema, as it can promote a Th2 inflammatory response through corresponding dendritic cell activation. Furthermore, Malassezia yeasts have the ability to bind C-type lectins, which are a diverse group of proteins that have the ability to recognize carbohydrate structures and, upon ligand binding, induce cellular responses with immune and nonimmune functions (128). In mast cells of atopic eczema patients, the expression of dectin-1 and the response to M. sympodialis exposure are modified compared to those of mast cells from healthy individuals (264), and this finding points toward additional host susceptibility factors that interact with Malassezia cellular components and result in the aggravation of atopic eczema. The activation of the C-type lectin Mincle in murine macrophages, through interactions with Malassezia yeasts, led to increases in the induction of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2), keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC), and interleukin-10 (IL-10) in a yeast/cell-dependent fashion, which was partly reduced in Mincle-deficient cells (340). Although this was originally observed for a strain of M. pachydermatis, binding to Mincle was further confirmed for the lipophilic species M. dermatis, M. japonica, M. nana, M. slooffiae, M. sympodialis, and M. furfur. Another C-type lectin, langerin, characteristically found in epidermal antigen-presenting Langerhans cells, was shown to bind extracts of M. furfur but not M. pachydermatis (79). However, effective binding to both of the latter species was observed when live cells and different Malassezia strains were used (312). Earlier studies showed that the uptake of M. furfur from human monocytes could be abrogated by coculture with soluble mannan and β-glucan (305), possibly through interactions with those receptors. It is most probable that the induction of cytokines from Malassezia cells is not mediated through a single pathway, as it has been shown that mast cell responses can be modulated by Malassezia through the canonical Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2)/MyD88 pathway but also through a different, not-yet-determined one (282). Interestingly, the contact of Malassezia cells with serum and subsequent opsonization increased their ability to induce IL-8 expression in a macrophage cell line and a granulocytic cell line (304). The differential stimulation of cytokine, chemokine, and adhesion molecule expression in host effector cells (Table 9) would eventually lead to either up- or downregulation of skin inflammatory processes, probably depending on the modifying interactions of still poorly understood cofactors. The resulting deviations in the tissue milieu may be further reflected by the divergent pathophysiologic manifestations of Malassezia-associated skin conditions that span the whole spectrum between overt inflammatory responses (seborrheic dermatitis and atopic eczema) and a distinct absence of inflammation, as in pityriasis versicolor. It can be further speculated at this point that complex interactions between Malassezia yeasts and their commensal or pathogenic microbial bystanders on the skin surface may not only mutually affect the survival and virulence status of both but also serve as decisive modifying cofactors of the pathogenesis of all Malassezia-related skin diseases.

Table 9.

Effects of Malassezia interactions with cellsa

| Species | Reference | Growth medium | Ratio of no. of Malassezia cells/no. of cells | Substrate(s) | Growth factor(s) of innate immunity | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. furfur | 306 | Dixon's agar | Live or heat-killed cells | Monocytic cell line (THP-1), granulocytic cell line (HL-60) | Up, IL-1α, IL-8; no change, IL-6, -8, and -12, TNF-α | ELISA and reverse transcription-PCR with visual comparison of the produced mRNA were employed, thus having restricted sensitivity; opsonized cells induced higher levels of IL-8 expression than did nonopsonized cells |

| M. furfur | 329 | SD liquid + Tween 40 | 1 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | No effect, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, MCP-1 | No effect on expression of cytokines tested |

| M. furfur | 28 | SD + olive oil + Tween 80 | 30 to 1 | HaCaT | Up, ICAM-1, IL-10, TGF-β1; down, IL-1α, TNF-α; no expression, IL-6 | IL-6 was not expressed, and this was attributed to the downregulation of IL-1α and TNF-α |

| M. furfur | 329 | SD liquid + Tween 40 | 1 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Up, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α; no change, MCP-1 | 1-24 h of stimulation, efficient cytokine production when coincubation was done for >6 h; M. furfur and all culture supernatants had no effect on cytokine production |

| M. furfur | 86 | SD + olive oil + Tween 80 | 30 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Up, HBD-2, TGF-β1, IL-10 | HBD-2 is protein kinase C dependent and has the ability to kill M. furfur cells at 50 μg/ml |

| M. furfur | 27 | SD + olive oil + Tween 80 | 30 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Up, TGF-β1, integrins (αv, β1, β3, β5), HSP70 | Activating protein 1 was considered to mediate expression, as this effect was inhibited by curcumin |

| M. furfur | 26 | SD + olive oil + Tween 80 | 30 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Up, TLR2, MyD88, IL-8, HBD-2 and -3 | TLR2-dependent increase in levels of HBD-2 and IL-8 |

| M. furfur | 161 | LNA | 20 to 1 | PHK16-0b, normal human keratinocytes | No significant expression of cytokines by microarray analysis | Absence of a T-helper-2-polarizing response of keratinocytes was attributed to minor contribution of this species to atopic eczema |

| M. furfur | 316 | LN broth | 27 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Up, IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10; no change, TNF-α | Stimulation of cytokine production depended on species, growth phase (exponential vs stationary), and removal of the lipid layer; nonviable, stationary cells of M. furfur produced the highest increase in levels of IL-6 |

| M. globosa | 161 | LNA | 20 to 1 | PHK16-0b, normal human epidermal keratinocytes | IL-3, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-10, IL-13, GM-CSF, IL-8, TIMP-1 and -2 | Slightly lower expression levels of cytokines in human keratinocytes, with GM-CSF, IL-5, and IL-10 being the most significantly induced |

| M. globosa | 316 | LN broth | 27 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Up, IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10; no change, TNF-α | Stimulation of cytokine production depended on species, growth phase (exponential vs stationary), and removal of the lipid layer; viable, stationary cells produced the highest increase in levels of IL-8 after lipid capsule removal |

| M. globosa | 160 | LNA | 20 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Thymic stromal lymphopoietin | Expression level of thymic stromal lymphopoietin was increased at higher calcium concentrations and was decreased when cells were treated with detergent |

| M. restricta | 316 | LN broth | 27 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Up, IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10; no change, TNF-α | Stimulation of cytokine production depended on species, growth phase (exponential vs stationary), and removal of the lipid layer; viable, stationary cells produced the second highest increase in IL-8 levels after lipid capsule removal |

| M. restricta | 161 | LNA | 20 to 1 | PHK16-0b, normal human epidermal keratinocytes | IL-4, monocyte inhibitory protein 3α, leptin, cutaneous-T-cell-attracting chemokine, placental growth factor | IL-4 was the only cytokine significantly expressed in normal human keratinocytes |

| M. restricta | 160 | LNA | 20 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Thymic stromal lymphopoietin | Expression level of thymic stromal lymphopoietin was increased at higher calcium concentrations and was decreased when cells were treated with detergent |

| M. slooffiae | 329 | SD liquid + Tween 40 | 1 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Up, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α; no change, MCP-1 | Achieved lower levels expression of cytokines than M. pachydermatis and levels equivalent to those achieved by M. sympodialis; culture supernatants had no effect |

| M. slooffiae | 329 | SD liquid + Tween 40 | 1 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Up, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α; no change, MCP-1 | 1-24 h of stimulation, efficient cytokine production at >6 h of coincubation; culture supernatants had no effect on cytokine production |

| M. slooffiae | 316 | LN broth | 27 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Up, IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10; no change, TNF-α | Stimulation of cytokine production depended on species, growth phase (exponential vs stationary), and removal of the lipid layer |

| M. sympodialis | 329 | SD liquid + Tween 40 | 1 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Up, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α; no change, MCP-1 | Achieved lower levels of expression of cytokines than M. pachydermatis and levels comparable to those of M. sympodialis; culture supernatants had no effect |

| M. sympodialis | 161 | LNA | 20 to 1 | PHK16-0b, NHEK | IL-6, bone morphogenetic protein 6 | Absence of a T- helper-2-polarizing response of keratinocytes was attributed to the minor contribution of this species to atopic eczema |

| M. sympodialis | 316 | LN Broth | 27 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Up, IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10; no change, TNF-α | Stimulation of cytokine production depended on species, growth phase (exponential vs stationary), and removal of the lipid layer |

| M. sympodialis | 282 | Whole extract | Bone marrow-derived mouse mast cells | Up, cysteinyl leukotrienes, IL-6, MCP-1 | The extract increased the level of production of cysteinyl leukotrienes in non-IgE-sensitized cells and IgE-mediated degranulation, IL-6, and ERK phosphorylation in IgE receptor-cross-linked cells; this activation was TLR2/MyD88 dependent and independent | |

| M. sympodialis | 264 | M. sympodialis extract | Bone marrow-derived mouse mast cells | Up, IL-6, IL-8, TLR-2, dectin-1 | Mast cells from atopic dermatitis patients demonstrated a defective expression of dectin-1 and an enhanced response to M. sympodialis | |

| M. obtusa | 316 | LN broth | 27 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Up, IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10; no change, TNF-α | Stimulation of cytokine production depended on species, growth phase (exponential vs stationary), and removal of the lipid layer; M. obtusa caused the second highest level of IL-6 production with nonviable, stationary cells after removal of the lipid layer |

| M. pachydermatis | 329 | SD liquid + Tween 40 | 1 to 1 | Normal human keratinocytes | Up, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α; no change, MCP-1 | Achieved the highest levels of expression of cytokines compared to those of M. sympodialis and M. slooffiae; culture supernatants had no effect |

| M. pachydermatis | 340 | Potato dextrose agar with olive oil | Increasing concentrations | Bone marrow-derived macrophages | Up, TNF-α, MIP-2, KC, IL-10 | Part of the induction of these cytokines was through the activation of Mincle |

SD, Sabouraud dextrose agar; IL, interleukin; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; ICAM-1: intercellular adhesion molecule 1; TGF, transforming growth factor; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein 1; HBD, human beta defensin; HSP70, heat shock protein 70; TLR2, Toll-like receptor 2; LNA, Leeming-Notman agar; LN, Leeming-Notman; GM-CSF, granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor; TIMP-1, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Conclusion

The interaction of Malassezia yeasts with the skin immune system is open to further research, and a prospective line of work would be analogous to that already under way for bacterial skin commensals. Species like Staphylococcus epidermidis have the ability to amplify the innate immune response through an increase in the constitutive expression of antimicrobial peptides, which are, however, active against the pathogenic species Staphylococcus aureus (328). A delineation of comparable interaction mechanisms would contribute to a better understanding of the significance of the reported differential colonization of lesional skin by distinctive, “pathogenic” Malassezia species subtypes compared to “nonvirulent” ones associated with healthy skin. Moreover, properly designed experiments could highlight the sequence of internal and external events in the skin microenvironment that mediates the development of Malassezia-associated diseases.

MALASSEZIA AND DISEASE

Pityriasis Versicolor

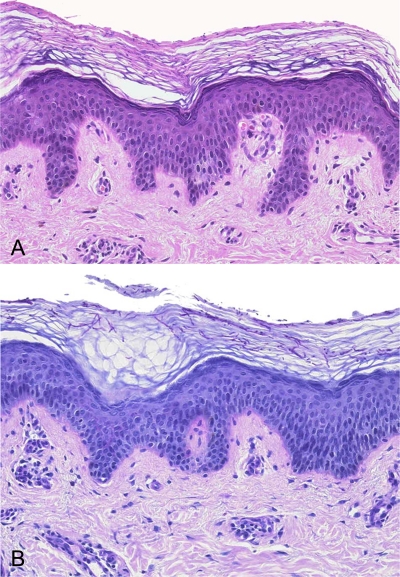

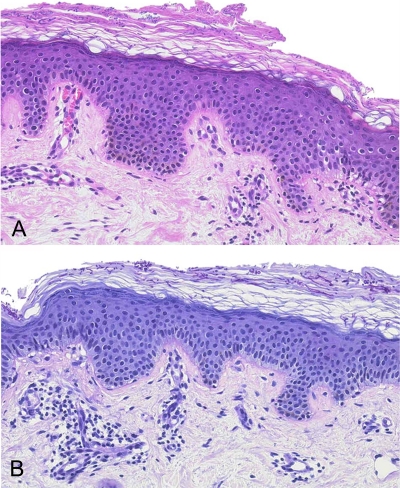

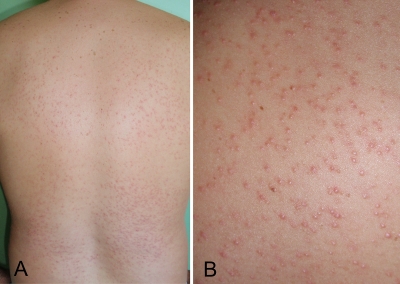

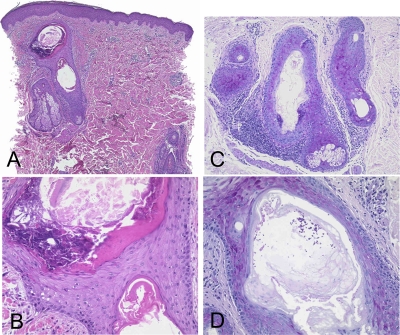

Pityriasis versicolor is the prototypical skin disease etiologically connected to Malassezia species. It is characterized by hypo- or hyperpigmented plaques that are covered by fine scales (pityron, Greek for scale), preferentially distributed in the so-called seborrheic areas of the skin surface, such as the back, chest, and neck (65) (Fig. 1). Vitiligo, pityriasis alba, and leprosy in corresponding areas of endemicity (211) are the main differential diagnoses of pityriasis versicolor. For the clinical differential diagnosis of this disease, Wood's light examination and the so-called “evoked-scale” sign (141, 284) have proven valuable. The latter sign consists of the provocation of visible scales by the stretching or scraping of a pityriasis versicolor lesion, by which the pathologically increased fragility of the lesional stratum corneum becomes evident. Although the exact structural alterations of the stratum corneum that lead to the increased fragility of the stratum corneum in pityriasis versicolor skin lesions are still unknown, it may be that the same aberrations could account for the partial disruption of epidermal barrier function and the increased transepidermal water loss observed for this disease (193). In the case of Wood lamp fluorescence, UV light is emitted at an approximately 365-nm wavelength, and the lesions of pityriasis versicolor will fluoresce reddish or yellowish green. Pityriasis versicolor does not permanently affect the structure of the lesional skin, although some cases that induced nonreversible skin atrophy have been reported (66, 269, 341). Histopathological examination of lesional skin biopsy specimens reveals a slight to moderate hyperkeratosis and, to a lesser degree, acanthosis. Depending on the extent of clinically manifested inflammation, the dermis contains a mild to almost absent superficial perivascular inflammatory cell infiltrate (Fig. 2) consisting mainly of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and, occasionally, plasma cells. Sometimes, mild melanin incontinence is observed. In the stratum corneum, there are numerous budding yeast cells and short hyphae (Fig. 2 and 3). Whether rare cases of pityriasis versicolor with interface dermatitis (Fig. 3) (302) are associated with the subsequent development of atrophying lesions is not known.

Fig 1.

Pityriasis versicolor in a 42-year-old female patient. The patient had relapsing disease for the past 6 years.

Fig 2.

Histopathology of noninflammatory pityriasis versicolor. Shown is the infiltration of the hyperkeratotic stratum corneum by Malassezia cells and hyphae; there is a distinct absence of an inflammatory cell infiltrate. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin stain; (B) PAS stain. Original magnification, ×200.

Fig 3.

Histopathology of inflammatory pityriasis versicolor. Shown is the infiltration of the hyperkeratotic stratum corneum by Malassezia cells and hyphae; there is a moderately dense perivascular inflammatory cell infiltrate in the upper dermis. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin stain; (B) PAS stain. Original magnification, ×200.

Pityriasis versicolor has been reported to appear in all age groups, ranging from infants 4 months old (84) to children (314), adults, and elderly individuals (85). However, the prevalence of this common skin disease is greater in the third and fourth decades of life, and its appearance is significantly affected by environmental factors such as temperature and humidity, patient immune status, and genetic predisposition. The annual incidence of pityriasis versicolor has been reported to range from 5.2% to 8.3% (93). Seasonal variations, although not consistent, are observed, with the highest incidence rates in September (314), spring and fall (55), or summer months (144). If not corrected for these variations, records on the prevalence of pityriasis versicolor in a population may be affected, but nevertheless, this disease is significantly more common in tropical and subtropical climates (93). The prevalence of the disease falls drastically in more temperate climates, as it was diagnosed in only 2.1% of young healthy males (mean age, 22 years) in Italy (156), with even lower rates in Sweden (0.5% of males and 0.3% of females) (147). The peak age-specific prevalence of pityriasis versicolor is among young adults 20 to 40 years old (189); however, in tropical/subtropical regions, such as India, the highest disease prevalence has been recorded for somewhat younger individuals, between 10 and 30 years old (89). Pityriasis versicolor is not an infectious disease, and hereditable factors decisively contribute to its appearance. A positive family history of pityriasis versicolor has been found for approximately 20% of patients (140, 144) in relevant studies without conjugal cases reported for married couples (144). Also, a polygenic additive-inheritance model of susceptibility to this disease was observed in one of these studies (144). The reported differences in the male-to-female ratio are suggestive of a sampling or reporting bias, as expected for a fluctuating disease without alerting symptoms. The burden of pityriasis versicolor might not be that evident in light-colored Caucasians but can represent social stigmatization when extensive depigmentation happens in colored skin.

Pityriasis versicolor and Malassezia.

Besides the consistent description of yeasts from pityriasis versicolor lesions, there are two main facts that permit an etiologic association of Malassezia with this disease: (i) it is more likely that a positive culture will be obtained from specimens taken from lesional skin than from macroscopically unaffected skin areas of either the same individual (255) or matched healthy controls (275), and (ii) the hyphal state is connected to pityriasis versicolor lesions, independently of the Malassezia species isolated, and seems to play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease (127). However, the expansion of hyphae in pityriasis versicolor patients is not confined to lesional skin. This points to a global propensity of the skin of these patients, at least at the time of overt disease, to support the hyphal growth of Malassezia species. Rates of isolation of hyphae from nonlesional trunk skin (42%) and the head (50%) of patients with pityriasis versicolor were lower than those reported for the lesions per se (100%) but were more than those reported for the skin of healthy individuals (6 to 7%) (217). As mentioned above, the Malassezia species initially associated with pityriasis versicolor was M. globosa (63), but current epidemiological data as well as the absence of distinct virulence factors confined to this species (151) do not permit a definite conclusion.

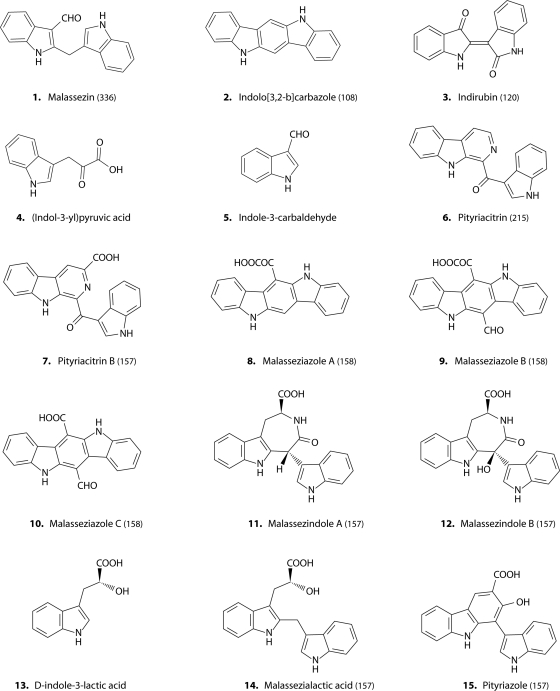

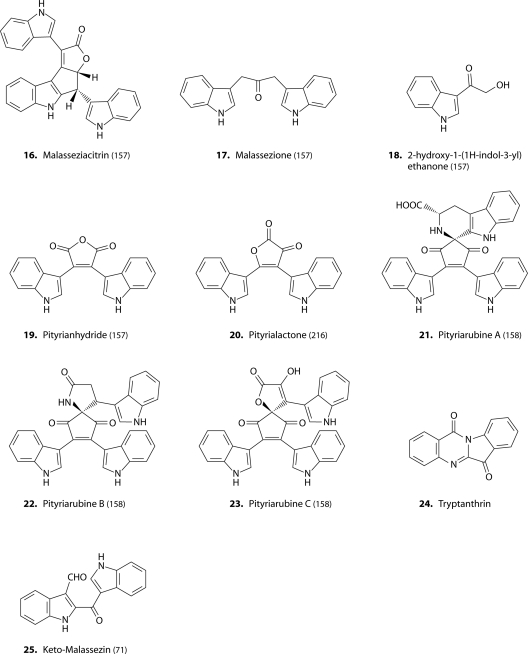

The involvement of Malassezia yeasts in the development of pityriasis versicolor illustrates the excellent adaptive mechanisms which this yeast possesses, with relevance to human skin physiology. In the two most common clinical forms of this disease, the hyperpigmented and hypopigmented forms, there is a significant fungal load on the skin but without any inflammatory alterations being observed. This has been partly attributed to the production of an array of indolic compounds produced by Malassezia species, in particular M. furfur (213), that have the ability to downregulate aspects of the inflammatory cascade (see below). Thus, indoles like pityriarubins impede the respiratory burst of human neutrophils (183), while indirubin and indolo[3,2-b]carbazole inhibit the phenotypic maturation of human dendritic cells (324). Additionally, malassezin was proposed to induce apoptosis in human melanocytes, and pityriacitrin was initially shown to have UV radiation-absorbing properties (206, 215). Due to its UV-absorbing capacity, it was proposed that it protects the underlying skin in the hypopigmented plaques of pityriasis versicolor (pityriasis versicolor alba) (190). However, this was not confirmed in subsequent in vivo and in vitro experiments (116), suggesting that additional substances may contribute to the clinically observed UV resistance of lesional skin. For the synthesis of these compounds, tryptophan aminotransferase, which converts l-tryptophan to indolepyruvate, has been inferred to be an important enzymatic step from data acquired from the phylogenetically close phytopathogenic yeast Ustilago maydis (355). The inhibition

of this enzyme by cycloserine led to the clinical reversal of hyperpigmented pityriasis versicolor lesions in vivo (214). The synthesis of these indoles is widely distributed among Malassezia species, and since this trait is also associated with the respective pathogenic potential of M. furfur (108) (P. Magiatis et al., unpublished data), the existence of additional biosynthetic pathways cannot be excluded.

Other metabolites that have been linked to the clinical presentation of pityriasis versicolor include melanin (107), azelaic acid (232), and other products of skin lipid peroxidation (80). The in vitro production of melanin by l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (l-DOPA) has been documented; however, the observation of melanized Malassezia cells in vivo in hyperpigmented lesions of pityriasis versicolor (107) still remains to be confirmed by relevant clinical studies. Finally, the proposed attribution of lesional skin hypopigmentation to the known competitive inhibition of tyrosinase activity by Malassezia-produced azelaic acid is most probably not relevant to the clinical setting, as this dicarboxylic acid cannot be synthesized in biologically significant quantities on diseased skin (196).

Treatment.

As mentioned above in the introduction, treatment for pityriasis versicolor will be discussed only briefly, and readers are referred to a recent relevant meta-analysis for further details (153). The goal of both topical and systemic treatments of pityriasis versicolor is not to eradicate Malassezia from skin but to restore the yeast's population dynamics to the commensal status.

In general, longer treatment periods (up to 4 weeks) and higher concentrations of topical regimens or doses of systemic agents result in higher cure rates, without, however, avoiding the increased relapse rate (153). In the latter case, prophylactic treatment regimens have been suggested.

Topical treatments are generally well tolerated and highly effective compared to placebo. Among the topical regimens, shampoos containing fungicidal concentrations of antifungal imidazoles, applied once daily for up to 4 weeks, were found to be adequately effective for the treatment of pityriasis versicolor (83). However, older studies also documented that nonimidazole topical agent formulations (zinc pyrithione shampoo, sulfur-salicylic acid shampoo, and selenium sulfide lotion) are sufficiently effective treatment options compared to placebo (21, 104, 276). More recently, pathophysiologically designed topical therapeutic approaches that target certain aspects of pityriasis versicolor pathogenesis are under clinical evaluation. Among them, quite promising approaches seem to be a 10-day application of a nitric oxide-liberating cream (168); the application twice daily of a 0.2 mol liter−1 aqueous cycloserine solution for 5 days, which resulted in the complete healing of hyperpigmented pityriasis versicolor with a rapid correction of the pigment deviation (214); and 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy for regionally confined lesions (179).

Extensive pityriasis versicolor can be treated successfully and safely with different oral antifungals (ketoconazole, itraconazole, and fluconazole) applied at a rather wide range of doses (range of up to 4×) and for treatment periods of 7 to 28 days (153). This is also the case with the use of newer imidazoles, like pramiconazole (100). Currently, the efficacy of single-dose regimens with different oral imidazoles to improve compliance is under clinical evaluation (78, 326).

Pityriasis versicolor prophylaxis approaches are not well documented. Two older trials reported that itraconazole at 200 mg twice daily, once per month, sufficiently reduced the rate of disease relapses compared to placebo (see reference 153). Optimal preventive regimens employing other oral antifungals or topical formulations have not been adequately evaluated to date.

Conclusion.

The relationship between pityriasis versicolor and Malassezia still remains an obscure one despite the frequency of this skin disease and the confirmed association with Malassezia. However, dissecting the mechanisms that trigger this skin disease would expand our knowledge on Malassezia and skin adaptive homeostatic mechanisms.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis (synonym, seborrheic eczema) is a relapsing skin disease that shows a predilection for the so-called seborrheic areas of the skin, such as the scalp, eyebrows, paranasal folds (Fig. 4), chest, back, axillae, and genitals, and is characterized by recurrent erythema and scaling. However, it should also be stressed that despite its designation, seborrhea is not present in seborrheic dermatitis (37). No widely accepted criteria regarding the diagnosis and grading of seborrheic dermatitis exist, and identification can constitute a clinical problem for psoriasis patients with facial involvement, a condition termed sebopsoriasis. Seborrheic dermatitis was initially described by Unna (318), and the association with Malassezia yeasts was accepted up to the middle of the 20th century, when the observed increased epidermal cell turnover gradually prompted researchers to characterize this condition as being intrinsic to the skin, analogous to psoriasis. The recognition of the role of Malassezia yeasts in seborrheic dermatitis pathogenesis was reappraised in the 1980s, when it was shown that the common denominator of the multiple treatment regimens used for seborrheic dermatitis was their antifungal activity (288).

Fig 4.

Seborrheic dermatitis in the nasolabial folds. The distribution of the lesions is typical; however, the seborrheic dermatitis can be characterized as severe, as the disease is extended into the parietal region and is associated with intense erythema and scaling.

The prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis is high, reaching 11.6% in a study from the United States, while dermatologists had diagnosed this condition in 2.6% of men and 3.0% of women in a relevant study (229). The disease is more common in certain populations, such as the elderly (181), and can be severe and therapy resistant in neuroleptic-induced Parkinsonism (31) and HIV patients (227). The occasionally observed clinical resistance to azole drugs in some cases of seborrheic dermatitis could be attributed to variable genotypes of the recently described M. globosa azole-metabolizing CYP51 enzyme (177).

The prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis peaks when sebaceous gland activity is high (15), during the first 3 months of life (infantile seborrheic dermatitis) and during puberty, but also when sebum excretion is reduced after the age of 50 years (61). Seborrheic dermatitis flares are also observed in the fall, when the level of sebum production is decreased compared to that in summer (345). The flare of disease could be associated with altered population dynamics, which would be affected not only by variations in sebaceous gland activity but also by modifications in other nutrients supplied by sweat, such as essential amino acids like glycine and tryptophan (148). It has been shown in vitro that glycine stimulates the fast growth of M. furfur, and when this amino acid is exhausted, yeast cells employ tryptophan as a nitrogen source, increasing the production of indolic metabolites (24). Such cycles of population growth, bioactive indole production, and subsequent deprivation of nutrients could result in insufficiently masked antigens and ligands on the surface of the yeast cells, which would result in the activation of the immune system. One study showed that increased numbers of metabolically active cells during summer resulted in higher rates of isolation in culture medium than in fall, although the actual DNA loads were equal in both seasons (6). The difference in the rates of active versus stationary/dead yeasts cells would result in the differential regulation of the skin immune response (316).

Seborrheic dermatitis and Malassezia.

Currently available data are not sufficient to define Malassezia virulence factors that lead to the appearance or exacerbation of seborrheic dermatitis. It should be noted that skin is the niche of Malassezia, and the interplay of the yeast with keratinocytes and immune cells determines the transformation of this commensal to a pathogen.

Environmental factors, such as UV radiation and antagonistic microorganisms, may constitute stress factors similarly for Malassezia yeasts and the skin. Thus, the ability of Malassezia to locally modify the immune response, in addition to host susceptibility and the production of secondary metabolites by the yeast, probably participates in eliciting and maintaining seborrheic dermatitis. Higher production rates of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligands in vitro by M. furfur have been associated with seborrheic dermatitis isolates (108). AhR is found in sebocytes (169), and its function is modified by epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (268, 301). The latter probably has a seborrheic distribution, as antibodies or small molecules that block its function cause a folliculocentric eruption with a seborrheic distribution (36), and the interplay of these two receptors was proposed previously (105). Thus, an initial approach to understanding the participation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in seborrheic dermatitis would be to study polymorphisms of the implicated downstream proteins (218) in patients and healthy controls and associate them with the indole-producing capacity of Malassezia strains that are isolated from their skin.

Current evidence demonstrates that seborrheic dermatitis results from a nonspecific immune response to Malassezia yeasts. Unfortunately, very few experiments were performed after the identification of new Malassezia species, and this is reflected in the available data (Table 9). Inflammatory markers recorded by immunocytochemistry of skin biopsy specimens from seborrheic dermatitis lesions show an increase in levels of inflammatory mediators (interleukin-1α [IL-1α], IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, gamma interferon [IFN-γ], and tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]) in the epidermis and around the follicles of diseased skin (98). These inflammatory markers are equivalent to those produced by Malassezia yeasts in experimental models (Table 9). However, this increase did not differ statistically from levels in adjacent, healthy-looking skin and varied only from levels on the skin of healthy volunteers (98), suggesting an individual susceptibility to the development of seborrheic dermatitis. Furthermore, Malassezia yeasts demonstrated an ability to induce immune reactions, depending on the species, the culture growth phase, yeast cell viability, and the integrity of Malassezia cells (316) (Table 9). The 2 species that are commonly isolated from human skin (M. globosa and M. restricta) demonstrate distinct profiles of proinflammatory cytokine production from epidermal cells, with M. globosa stimulating the production of significantly more cytokines than M. restricta. However, the net effect of this cytokine synthesis, i.e., immune stimulation or tolerance, cannot be extracted from published data, as experimental conditions are not comparable (Table 9). For example, even the use of different culture media could result in different compositions of the lipid layer that covers the cell wall of Malassezia, resulting in a variable modulation of the immune system (316). In a recent study, the levels of binding and activation of the C-type lectin Mincle caused by Malassezia yeasts were higher than those of other fungi (340). However, the growth of Malassezia yeasts in a medium with only olive oil as a lipid source would have resulted in an insufficient masking of mannose residues that could subsequently be recognized by Mincle (340).

Another virulence factor intrinsic to Malassezia yeasts that has been discussed in association with the pathogenesis of seborrheic dermatitis is the production of phospholipases and the response to β-endorphin. The increased level of production of phospholipase after β-endorphin stimulation has been shown only for pathogenic M. pachydermatis strains; however, there is evidence that this also applies to lipophilic Malassezia species, although to date, this has been reproducible in vitro only for M. furfur (323). However, sebum production is increased by β-endorphin (354), and the demonstration of a functional μ-opioid receptor in pathogenic and nonpathogenic M. pachydermatis strains (41, 42, 44) has been shown. This points toward the existence of an equivalent sensory pathway in the lipophilic Malassezia species that could assist in the preparation of the yeast for a better utilization of sebaceous lipids. The aberrant production of Malassezia phospholipases on the skin could result in the removal of epidermal lipids, disruption of the epidermal barrier function, and the development of seborrheic dermatitis when sebum production is constitutionally decreased. Phospholipase production is a well-established virulence factor in Candida albicans (187), and the existence of environmental sensory G-protein-coupled receptors in fungi has been shown (339). Mining of the sequenced genome of M. globosa would lead to the recognition and detection of relevant genes in Malassezia and their association with the pathogenetic potential of the respective strains.

Malassezia, seborrheic dermatitis, and HIV/AIDS.

Seborrheic dermatitis in HIV/AIDS patients is more severe and more recalcitrant to treatment and advances with the stage of the disease (227). HIV/AIDS is associated with the development of multiple skin diseases; however, seborrheic dermatitis is the most common, with its reported prevalence ranging between 20 and 40% in HIV-1-seropositive patients and between 40 and 80% in those with AIDS (317). The keratinocyte response to stress signals (258) as well as the cross talk of Langerhans cells with CD-4 memory lymphocytes are modified in HIV/AIDS patients, and the skin immune system is disorganized by the destruction of both subsets of immune cells (249). Data from Malassezia population studies of HIV/AIDS-associated seborrheic dermatitis are inconclusive, as increased numbers of Malassezia yeasts have been found on the skin of HIV/AIDS-positive volunteers without seborrheic dermatitis (245) and on the healthy skin of HIV-positive seborrheic dermatitis patients (245) compared to controls. However, decreased Malassezia numbers in HIV patients with seborrheic dermatitis (227, 335) have also been reported, calling into question the implication of Malassezia yeasts (335). It is conceivable that as HIV/AIDS advances, the skin immune system disintegrates and, therefore, multiple treatment-resistant viral, bacterial, and fungal dermatoses develop (165), challenging the survival of commensal Malassezia yeasts and prompting them to express virulence factors.

Malassezia and infantile seborrheic dermatitis.

Infantile seborrheic dermatitis describes a characteristic, usually nonpruritic, eczematous or psoriasiform eruption that usually appears between the second week and the sixth month of life and can involve the face, scalp, trunk, and sternum area, individually or in any combination (15, 343). The lesions might coalesce, especially on the face and flexures, but when on the trunk, they are more distinct. The microbial flora of the mothers seems to pass to the lactating infant during breastfeeding and readily colonizes the skin within the first 24 h of life (G. Stamatas, unpublished data). During rapid expansion in order to cover the infant skin biocene (i.e., the absence of living microorganisms), the interaction with the still immature neonatal immune system and the epidermis, itself adapting to its new environment, could cause seborrheic dermatitis.

Malassezia and dandruff.

Dandruff is a poorly defined, frequent, pathological skin condition confined to the scalp and is characterized by flaking with minimal to absent inflammation. Dandruff improves after reducing the population of Malassezia yeasts on the scalp with proper treatment (133). However, the experimental application of oleic acid has resulted in the production of dandruff lesions only in dandruff-prone individuals (75). Oleic acid in the scalp is produced from the hydrolysis of triglycerides by Malassezia lipases (74). A variety of lipases has been shown to be encoded by M. furfur (35), M. pachydermatis (285), and M. globosa (76). The expression of M. globosa lipases on the scalp of humans has been shown (76), increasing the significance of this observation and supporting a link between clinical observations (75) and experimental data (35, 76, 285).

Conclusion.

Current data highly implicate Malassezia yeasts in the pathogenesis of both seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff. However, despite the global distribution and significant economic burden that these skin conditions inflict, amazingly, limited research has been conducted to date to improve our knowledge concerning the exact role of Malassezia in their pathogenesis. Nevertheless, both seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff represent excellent models for understanding the species- and strain-specific metabolic and immunogenic potential of Malassezia yeasts as well as host susceptibility.

Atopic Eczema

Atopic eczema (166) is a multifactorial skin disease with a diverse genetic background, and it is characterized by a distinct constellation of clinical symptoms and signs. Currently, the interplay between an inherently defective skin barrier (60) and an aberrant skin immune response (77) constitutes the most widely accepted pathophysiological concept for the understanding of the pathogenesis of this skin disease. Malassezia yeasts have species- and strain-specific properties that support a distinctive, probably more than simply modifying, role in the pathogenesis and maintenance of atopic eczema. Despite the fact that there is no definite conclusion regarding the timing of events that result in the development of atopic eczema (a barrier defect predisposes one to immune stimulation, or an immune defect causes barrier damage) (30), resident Malassezia yeasts could actively participate in the deregulation of the skin homeostatic mechanisms.

Malassezia and atopic eczema.