Abstract

Purpose

Pakistan is a patriarchal society in which male opinion leaders play an important role in determining health-seeking behaviors pertaining to family planning (FP) among their respective communities. This research focuses on cataloguing the perceptions of opinion leaders (clergymen, health professionals, and social workers) about the barriers for using services and practical solutions for promoting FP in the slums of Karachi, Pakistan.

Materials and methods

A qualitative study using an open-ended, semistructured interview schedule with hypothetical scenarios and in-depth interviews with a purposive sample of 45 opinion leaders (25 mosque imams/clergymen, 12 nonallopathic health professionals, and eight social workers/activists) was conducted in 2006–2007 in Karachi, Pakistan. Transcripts were coded thematically utilizing NVivo by using an adapted constant comparison analysis process as described by Strauss and Corbin.

Results

Seven key themes were derived from the in-depth interviews. Five themes provide insight into the opinion leaders’ perceptions of barriers to FP and modern contraception methods. Among the barriers religious taboos and cultural pressures were particularly note-worthy. Two themes offered opportunities for more effective development and implementation of FP programs.

Conclusion

It is evident from the study that opinion leaders in the community and the clergy lack the understanding of the importance of birth spacing. However, because they have a great deal of influence on the community at large, it is imperative to interact with them to build their capacity in order to propagate the messages of FP and improve maternal health and reproductive health in general.

Keywords: religious leaders/community imams/clergyman, health professionals, social workers

Introduction

The socioeconomic conditions, religious beliefs, and cultural values of a society are important factors in the acceptance or adoption of innovation. Before the introduction of any change, exhaustive investigations of the socioeconomic setup, religious beliefs, misconceptions, and cultural values need to be carried out. In the past, efforts made without giving proper weight to social, economic, religious, or cultural values have either badly failed or resulted in poor adoption. Government initiatives in Pakistan, especially population-based programs, have been caught in a vicious cycle of hostility (eg, the State-funded family planning [FP] programs).1 Religion predominates people’s lives and has been cited as an important factor in reproductive health issues such as contraception, procreation, and abortion.2–4 Pakistan has a composite culture, with many ethnic groups and socioeconomic strata that include Muslims in the majority at over 95 percent, with Christians and Hindus at approximately 5 percent. More than 75 percent of Muslims are followers of the Sunni schools of thought, and the remaining 20%–25% belong to the Shiite system.5 For the Muslim population, in particular, the people are religious and family centered, with the “family” understood to extend beyond the nuclear family; it is not uncommon to have three generations residing under one roof or within close proximity to each other and pooling their resources.6 In addition to being a low-middle income country, with more than 22 percent of its population living below the national poverty line and 61 percent living below $2 a day, the exact health care costs spent on maternal health and its related conditions are not available.7 However, the per capita government expenditure on health in 2009 was $8.86.7 Adding to the general underfunding of health care, deteriorating maternal health affects the costs and provision of hospital stays and medicine, laboratory testing, treatment coverage, and screening.7,8

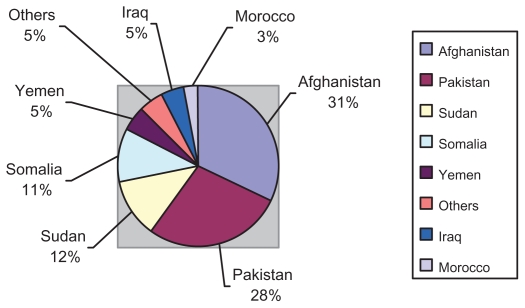

As a result, more than 80 women die daily in Pakistan (approximately 30,000 annually) due to preventable complications related to unwanted pregnancy. In 2008, India, Pakistan, Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Congo contributed more than 50% of all maternal deaths across the globe.9,10 Of those, an estimated 52 maternal deaths occur daily in rural Pakistan, based on the urban-rural divide. In addition, 420,000 children die before the age of 5 years, and 16,000 die in the first month after birth.10 Figure 1 shows the proportion of maternal deaths by country in 2002–2005.11–13

Figure 1.

Proportion of maternal deaths by country in 2002–2005.

Marriages at young ages (less than 18 years), female literacy (which is very low nationally [36%] and even lower in rural areas of the country), high fertility rate (4.1%), and intensifying poverty levels are indicators for an enhanced need for contraceptive utilization in Pakistan for birth spacing.14 The data from the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) 2006–07 reveal a relatively low contraceptive prevalence of 29.6%, with use of modern methods of only 21.7%.14

More than half (55%) of the women want to practise FP; however, the services and programs fail to meet the demand and leave an unmet need for contraception of 25% at a national level. In addition, the unmet need for contraception is higher (26.4%) in the rural areas compared with urban areas (22%). Interestingly, women with no education have the highest unmet need for FP (26%), and those with higher education have the lowest unmet need (18%).

Similarly, the current use of FP is very low in women with no education (25%) and relatively very high amongst the women with primary, middle, secondary, and higher education (34%, 37%, 39%, and 42.5%, respectively). Of those women who do not practise FP, 58% quoted fertility-related reasons (ie, desire for more children), 23% quoted their husband’s opposition to use of contraceptive methods, and 12% quoted method-related misperceptions and fears.

According to the 2006–2007 PDHS, 26% of all births are unintended.14 Of those, 11% are unwanted births and 15% are mistimed. In addition, an estimated 890,000 induced abortions occur annually. The abortion rate is 29 per 1000 women aged 15–49 years.15 This is a medium estimate; the low and high estimates are 25 and 31 per 1000 women, respectively. Therefore, in Pakistan, abortion accounts for one in seven pregnancies, mainly in places where contraception rates are very low and where the rate of unwanted childbearing is very high, such as the present study target areas. In addition, an estimated 197,000 women are treated annually for unsafe abortions. The rate of unsafe, induced abortions is 6.4 per 1000 women aged 15–49 years (Table 1).15

Table 1.

Regional estimates of unwanted pregnancy and induced abortion in South Asia

According to the 2006–2007 PDHS, 7% of currently married women who have never been users of contraceptives identified religion as their central reason for never using contraceptives, but this proportion is believed to be much higher in rural areas. As a result, religious opposition and misinterpretation of FP slow down the approval of modern methods of contraception, even among those who want to space out their children in Pakistan.

Moreover, in the public and private centers/clinics located in the urban areas, FP services and commodities are accessible and available. However, in rural areas, visibility of FP services is still poor. In outreach areas, it is either not accessible or not available. For instance, there are more than 12,000 first-level care facilities located in the rural areas, including rural health centers, basic health units, and family welfare centers, but more than 30% of these facilities are nonfunctional.7 In addition, the majority of the married women of reproductive age (MWRA) (48.2%) have accessed modern FP services from the public sector – namely from government hospital or reproductive health services centers (32.4%) mainly in the urban areas, but the women’s health workers (8.4%), health visitors (2.6%), family welfare centers (1.8%), rural health centers (1.6%), and others (1.5%) are not meeting the rural needs.14 Likewise, the private medical sector also contributes, with 30.1% of MWRA accessing FP services from private clinics or nongovernmental organizations; pharmacies/chemists; and private doctors, dispensers, or other private medical staff (16.2%, 9%, 3.3%, 1.2%, and 0.4%, respectively). Likewise, 10.3% of the MWRA obtained these services from “shops” other than pharmacies/chemists.14

Many studies have focused mainly on the female perspective of general maternal and reproductive health;16–22 however, very few studies have attempted to understand the male viewpoint.1,23–25 Men and women are two integral parts of society, but men’s involvement as a primary target group in the context of FP is one of the most important elements that affect success in the adoption of modern contraceptive methods, particularly in Muslim society, where men are dominant and serve as important figures who influence the decision making of women. This complexity is evident from research published in the Pakistani context over the period of time since 2004.1,23,24,26

Moreover, in a society like Pakistan, where formal education is not widespread, the majority of people live in rural areas (more than 65% of the population). Rural-based people tend to have a conservative outlook, and clergymen have much influence over them.23 After working/living in the country for many years, it is clear that, in rural areas, not only local religious leaders (community imams or clergyman) but also health professionals and social workers are considered to be opinion leaders. Opinion leaders such as community imams/clergymen (local religious leaders), village elders, and community-based social activists and workers play an important role in determining health-seeking behaviors, particularly pertaining to birth spacing and contraception.1,27 Religious leaders, in addition to the authority they exert in the domain of morality, ethics, and faith, have a great influence on maternal and child health. It is stated in a recently published review that “given the important role of village elders, clergymen and religious scholars in society, their social approval for family planning will be required to fulfil the unmet need.”26

Therefore, it is important to analyze the perceptions of opinion leaders regarding maternal and child health and, in particular, regarding FP. Moreover, by virtue of the preponderant role of the religion,1,27 understanding the role of opinion leaders in educating the community on health matters becomes very important.

In the present study, the opinion leaders were asked about their beliefs and perceptions regarding FP and practices of birth spacing, current use of modern contraceptives amongst married women of reproductive age 15–49 years residing in their areas, and prospective channels through which opinion leaders could be approached in order to gain their cooperation in furthering the aims of FP programs in Pakistan. This information was also thought to be useful for determining the role of opinion leaders in educating the community about issues of reproductive health and fertility control. Future work and recommendations can be developed from this study to promote and improve FP initiatives in Pakistan.

Materials and methods

The study, which was conducted from December 2006 to February 2007, was based on the theory of qualitative research, utilizing in-depth interviews for data collection and involving three types of opinion leaders: 25 community imams/clergymen working in the mosques, 12 nonallopathic health professionals, and eight social workers/activists. The reason for recruiting these three types of opinion leaders is that they have a major influence in all the decisions taken in the community, and their opinions are considered highly significant. The clerics are considered an authority on the religious aspects of all matters (including FP), whereas the nonallopathic health professionals are sought for health advice. For some community members they are considered to be just as important as an allopathic physician. The majority of health professionals are homeopaths, nurses, medicine dispensers, and traditional healers in the target area.28,29 All the respondents were male, as the researcher could not locate any female opinion leader in the target area for research study. In such community setups there are rarely any female opinion leaders in these decision-making positions. That is all the more reason why the aforementioned male opinion leaders should be involved in obtaining FP services for the community’s women.

A purposive sampling approach was employed, and the participants were recruited through community contacts and a local nongovernment organization. Interviews were continued to the point of information saturation. The most commonly used form of nonprobabilistic sampling is purposive sampling. The concept of “saturation” is the point at which no new information or themes are observed in the data, the cutoff between adding emerging findings and not adding them, or when the researcher is no longer hearing or seeing new information. Utilizing the data from the present study involving 45 in-depth interviews with opinion leaders such as 25 clergyman/imam, 12 nonallopathic homeopathic doctors, and eight social workers in the slums of Karachi, the author systematically documented the degree of data saturation and variability over the course of thematic analysis. Based on the study data set, it was found that saturation occurred within the first 35 interviews, although basic elements for metathemes were present as early as 16 interviews. Variability within the data followed similar patterns, and the author had to discontinue collecting the data, as there was no need to continue interviewing people once it was found that further interviews were not adding to the findings or were repeating what had already been found in the previous interviews. The in-depth interviews comprised open-ended, semistructured questions and the use of hypothetical scenarios about FP and maternal health, which were based on the theory of qualitative research (Table 2).

Table 2.

Interview schedule

| Question | Scenario | Scenario-related question |

|---|---|---|

|

|

What is your point of view and suggestion/s in the case? |

|

|

What is your point of view? |

|

|

What advice will you give him? What are your views on family planning or spacing methods? In your opinion, can a mother be healthy when using these methods? |

|

Gulshan-e-Sikandarabad and Masan Road (http://maps.google.com/maps?q=Masan+Road,+Karachi,+Sindh,+Pakistan&hl=en&ll=24.821664,66.985375&spn=0.015152,0.01929&sll=37.0625,-95.677068&sspn=53.564699,79.013672&z=16&layer=c&cbll=24.821664,66.985375&cbp=12,0,,0,0&photoid=po-50873992), which are two large urban slums situated in the metropolitan city of Karachi, Pakistan, were chosen as the study area because of their easy access and the feasibility of conducting the study with limited resources. The two selected slums, collectively, have a population of approximately 50,000 people, most of whom are illiterate Pashto-speaking migrants from northern Pakistan, working as laborers or transporters.30,31

All the interviews were recorded and transcribed in Urdu and then translated into English by the researcher, who was fluent in both languages. Verbatim notes of in-depth interviews were transcribed to provide a record of what was said in the interviews. Recordings were made where study participants allowed this. Out of the 45 total interviews, 14 interviewees refused to record their interviews due to personal reasons. Twelve were community imams/clergymen and two were health professionals. Transcription and translation of data provided us with a descriptive record. The final interview notes were shared with the interviewees for validation. Another check of the validity of transcriptions and the translations was done by a colleague who had not participated in the study until then.

Transcripts were coded thematically utilizing NVivo software (v 8; QSR International Pty, Doncaster, Australia). These codes were then refined, combined, and further categorized across transcripts to develop more general codes for further analysis by the researcher, in accordance with the themes that were frequently and consistently emerging from the data. This was done via an adapted constant comparison analysis process, as described by Strauss and Corbin.32 Key findings and responses were aggregated as subnodes and later analyzed to develop the thematic areas. Information gathered from the interviews was then triangulated with literature to find similarities and differences on the issues around FP and maternal health. Interviews were continued to the point of information saturation. Participants provided informed written consent prior to submitting to the interviews in private rooms. Each interview lasted between 35 minutes and 50 minutes. The ethical approval for this study was obtained from the School of Public Health, The Secretary, Human Research Ethics Committee, Office of Research and Development, Curtin University of Technology, Perth, Western Australia, and the City District Government Karachi.

This study was conducted as part of the author’s Master of Public Health research dissertation during January 2006 to December 2007. The author was employed at Marie Stopes Society (MSS) Pakistan from August 2008 onwards. Therefore, the author and this study have no relationship with MSS Pakistan. The author, who was the principal investigator of this study, conducted all 45 interviews himself.

Results

Seven key themes were derived from the in-depth interviews. Five themes provide insight into the opinion leaders’ perceptions of barriers to FP and modern contraception methods. Two themes offered opportunities for more effective development and implementation of FP programs.

Capacity to build understanding and cooperation

It is important to recognize, first of all, that the opinion leaders spoke as one voice about the value they attached to their work and the esteem in which their community seems to hold them.

People come to us to seek advice and suggestion, whether it is some personal or family dispute, economical hardships, or even childbirth. We guide them and provide them such services free of charge and in the light of Islam and Shari’a. (Community Imams-3)

Furthermore, opinion leaders felt that their roles were relevant, and that it was important to create an environment where meaningful cooperation could be built among leaders on the issues of maternal and family health, childbirth, child spacing, and FP.

Most importantly, in my community, people need continuous counseling and advocacy to overcome such pressures; practically, it is impossible for one individual to do this. It is teamwork that involves the local doctors, religious leaders, and [social workers] to work as a team because as a team we can help our fellow residents to solve their problems. (Health Professionals-5)

Significantly, the health professionals identified imams as an important influence on people, especially when it comes to issues such as childbirth, spacing, contraception, and abortions. They advocated holding sensitization workshops and advocacy seminars in order to provide information platforms to community imams/clergymen, where an open dialog could be facilitated in order to address the prevailing issues and misconceptions amongst them.

Religious leaders of this area can be very effective in helping to disseminate knowledge about spacing and family planning. Most people seek advice from these religious leaders and these [the religious leaders] must be provided with some formal training on spacing and family planning. (Health Professionals-4)

Health professionals considered themselves to be an important link between people and the imams in delivering health-related messages to the community. The imams, in turn, described how teamwork can better meet the counseling and advocacy needs of people in the target area when dealing with these issues. Advice from doctors and other health professionals supports and validates the religious leaders’ positions on childbirth, spacing, contraception, and abortion.

I suppose local doctors are the best source to provide good advice on the issue of childbirth, as we, the religious leaders, inform the people what is right and wrong according to Islam and Shari’a. So now it is not just the religious leader who can make a decision over the health of a commoner; rather, he would need a medical expert to validate his judgment. (Community Imams-16)

As per the previous quote, it is interesting to know that the community members consider local health care providers to be an equally important source of advice and counseling as they think of their clergy, which shows that health care providers in many aspects wield similar reverence/influence as the cleric for the community.

Opportunities for more effective development and implementation of FP programs

Two potential solutions to improve acceptance of FP and modern contraception methods arose from the research: (1) people in the area would be willing to accept new ideas as long as these are introduced taking into account cultural sensitivity, and (2) the common ground amongst opinion leaders, once demonstrated through results such as those arising from this study, will lead to a preparedness to work together on issues of FP and even allowing abortions where the health/life of the expecting mother is in jeopardy.

Willingness to accept new ideas

Opinion leaders felt that, generally, people living in the target area would be willing to accept new ideas eventually. But, according to them, birth decisions, use of contraception, and child spacing were sensitive issues, and any moves toward change must be made cautiously. The leaders affirmed that people need repeated prompts and a persuasive contact to think on such issues.

People are open to accept new ideas and ways of treatment. When we talk to them about newer ideas for improving the health of their entire family they give us blessings for letting them know such beneficial ideas. (Health Professional-7)

I am strongly convinced that the people will accept these new ideas of improving maternal health through proper birth spacing. A few won’t accept new things; however, the majority will accept it. People residing in this area want someone to come and tell them about good and beneficial things for their health. (Community Imam-8)

Barriers to family planning and modern contraceptive methods

Mothers are not machines

A key theme that arose was that opinion leaders felt that husbands and in-laws treated mothers as “machines.” The following comments from a health professional and a community imam, respectively, narrate the respective respondent’s group views:

Having consecutive pregnancies creates a double burden on mothers’ health. This is medically, religiously, socially, and culturally not acceptable. Women are not automatic machines. Even when the husband is financially stable, this does not mean to have a baby every year, especially when the wife is very young and weak. (Health Professional-6)

Mother is not a machine for just producing children, and even machines need a break. I will tell the husbands that a woman can give birth to a healthy baby only when the machine is working properly. If the machine is having some problems, then how can you expect it to produce healthy babies? I will emphasize timely spacing and providing a good diet to improve health, and when a mother is healthy, everything will return to normal. (Community Imam-1)

There was considerable common ground in the opinion leaders’ views concerning the negative impact of a culture of rapidly consecutive pregnancies.

Mutual decision-making should be valued

Health professionals voiced that mutual decision-making was the main issue that caused differences between couples and often led to disputes. Social workers also spoke about male illiteracy and misinterpretation of religious teachings as the causes of this problem.

Male illiteracy is the main and basic reason behind this situation. Secondly, the cultural pressure and religious concerns also provide tough opposition. If educated, people then can also resist social pressure and religious concern. (Social Worker-1)

Although the emphasis varied, there was consistency among opinion leaders about the important role of education and religion in supporting a mutual decision-making process with regard to spacing of childbirth. The following comment reflects the same perspective of the majority of the local religious leaders or community imams:

Having children or not having them must depend on the will of the husband and wife, and this is what the law of Shari’a says. If a husband doesn’t want to have a child and the wife wants to have one or vice versa, then whatever is to be done has to be done by mutual consultation. Education, culture, and, above all, religion play an important role in decision making. (Community Imam-4)

Results from a small-scale recent study from Pakistan documented that the important factors that motivate men to participate and use contraceptives include formal education, desire for more children, awareness of a method, and income.33 Both spouses, husbands and wives, confirm educational acquisition as a deciding/causal factor for contraceptive use.

Pressures and taboos compound the problem

Opinion leaders generally saw physical and verbal abuse of mothers, which is a common tactic of husbands and in-laws, to be a cause of problems affecting maternal and family health. Both the health professionals and imams condemned this domineering attitude. Leaders felt that the reason for such abuse was probably a lack of education. A health professional voiced this viewpoint:

Our society, especially the in-laws, puts undue pressure on women who don’t get pregnant in their first year of marriage. Verbal and physical abuse from the in-laws is also very common here. (Health Professional-4)

Social workers felt that religious pressure was also an additional factor. A social worker expressed it this way:

Here, women are not allowed to post their comments or discuss them, not even allowed to give suggestions or advice. In these areas, people have wrong interpretations of religion, for example “Men are rulers and women are only supposed to serve them.” Women have no options other than to obey their husbands. (Social Worker-5)

Likewise, the following quote reveals the perspective of the majority of community imams:

Women have been blackmailed and pressurized by their relatives, especially in-laws, over childbirth. (Community Imam-7)

Views on abortion differ

There were disagreements among the three groups of opinion leaders regarding the permissibility of abortion. Imams concurred that abortion was permissible if the life or health of the woman was in jeopardy; otherwise, abortion was illegal and tantamount to murder. One religious leader or community Imam commented:

This depends on the health of a mother; she is not allowed to go for an abortion unless the pregnancy is a threat to the mother’s life. After the fourth month, the face and figure are completed and the organs of the fetus are formed; then, the abortion becomes murder. (Community Imam-1)

The health professionals and social workers supported the option of abortion when medically justified. In their view, abortion must be legalized, as multiple illegal centers are operating in their area, offering abortions by untrained and unskilled nurses and traditional healers.

Until 1997, abortion was permitted to save the life of the mother, but then the law was amended in the light of injunctions of the Quran and Sunnah. At that point, abortion also became legal in cases where it was necessary to provide treatment to the mother.34

Child spacing and religious contexts

All the participants agreed that spacing pregnancies and taking into account the number of pregnancies help to keep the mother in a better physical condition. They felt that the children would be healthier too, as frequent and consecutive pregnancies contribute to compromised maternal health and infant morbidity. However, a number of imams said that only when a future pregnancy could be fatal to the mother could spacing be condoned. For imams, poverty was not a legitimate reason for birth spacing.

But if you do spacing or family planning for the reason of how are we going to feed the family, then this is prohibited; however, if the health of the mother is the reason, then there is some possibility to accept. (Community Imam-12)

All the health professionals and social workers were in agreement with this sentiment:

Here, some people have given a wrong impression about spacing and family planning, that it completely stops reproduction in a woman or it makes our women permanently infertile. Almost all of these impressions are being spread by the local men, who are influenced by religion, society, and culture. (Health Professional-3)

Social workers placed partial blame on religious leaders for providing incomplete or wrong interpretation of religious texts to the people.

Spacing and family planning are both necessary and provide benefits to both mother and their children, and I personally believe that there should be at least 2–2.5 years of spacing between successive children. (Social Worker-10)

Thus, pressures and taboos compounding the problem, especially from the in-laws,35 and differing views on abortion due to different options concerned with religious permissibility are the major reasons why acceptance of FP and issues related to abortion still have a lot of ground to cover.

Discussion

In addressing the question of FP from an Islamic perspective, it is necessary to consult the various sources of guidance within the religious tradition. These include the Quranic revelation, the prophetic traditions, and one’s inner moral capacities of discernment. In addition, it is valuable to inform oneself of the relevant aspects of the Islamic legal legacy as well as all the contemporary advances in knowledge on the subject. Governments around the world, including many in the Islamic world, support FP programs to enable individuals and couples to choose the number and timing of their children. The development of modern contraceptives, organized FP programs, and international agreements on FP have given new impulse to old debates such as that Muslim individuals and couples are permitted to use FP or that governments can be involved in providing FP information and services.

The success of FP programs, then, appears to be significantly entwined with the Muslim religion. It has been shown in several studies conducted in the Islamic countries of Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia, Kuwait, and Iran that involving and incorporating the opinions of Muslim religious leaders in the national family programs resulted in the leaders’ formal support for the programs. Furthermore, the leaders provided their assistance in increasing contraceptive prevalence in these countries.36–38 Available data on the Iranian situation asserted that a government-funded FP program succeeded in achieving its target to reduce the country’s fertility rates by reducing total fertility rates up to 64 percent.39 Iran gained this success by incorporating evidence-based policies that provided better levels of life expectancy, literacy, and income to all Iranians. Similarly, the Indonesian FP program also demonstrated success through public sector involvement with high levels of contraceptive prevalence.40 Over time, however, the contraceptive prevalence has now reached a plateau in Indonesia due to reduced international funding, decreased public sector involvement, and decreased supply of FP products. In addition, public health studies from Jordanian perspectives documented that the majority of the people and religious leaders from Jordan approve of FP and contraception and, to a larger extent, believe that FP is agreeable with Islam.41 Finally, the data from Kuwait also reveal the high rate of contraceptive use and low levels of unmet need for contraception in the country, which is mainly attributed to the free provision of these products and methods at government-controlled health care clinics and hospitals.42 Likewise, the government of Pakistan also implemented a State-funded FP program approximately 60 years ago; however, the role of evidence-based policies was almost negligible. Instead, a model was adapted and implemented without contextualizing this model according to needs of the people of Pakistan.

This study provides insight into the perspectives of clergymen/mosque imams, health professionals/physicians (nonallopathic), and social workers regarding maternal health and FP. Within limitations of the findings of the present study, from the Ulama conference held in Pakistan and some other public health interpretations, the current research provides insight to a consentient call for religious and other opinion leaders to take more personal responsibility for maternal health and FP.18,43–46

In these communities, the leaders identified the need for bringing about radical change in societal attitudes and behaviors to deal with unfair treatment of mothers as machines, to enlist action points arising out of cultural and religious traditions, and to enhance understanding among themselves and community members, with reference to child spacing and planning. Harnessing the potential influence of opinion leaders on health-related issues is seen as a way forward that will definitely contribute toward improving the acceptability of contraceptive use and misperceptions related to birth spacing to some extent. The common ground for working on FP programs for all three groups of opinion leaders is to achieve goals to increase contraceptive uptake and thereby improve maternal health in these two areas. Working with opinion leaders can enhance their capacity for bringing about an overall social change vis-à-vis use of contraceptives for birth spacing and to advocate its benefits to the health of the mother and child.

Therefore, one task for future work in this area is to build capacity for understanding and cooperation among opinion leaders so that they are better able to resolve FP issues. One way for capitalizing this tangible recommendation is by making education and counseling a compulsory basic component for the opinion leaders in all FP programs. Furthermore, the education component of the FP program should focus on religious leaders to promote advocacy concerning health promotion and reproductive health. Capacity building of clergy in Pakistan can be a bit challenging due to different schools of thought or religious sects. Nevertheless, the idea of focusing on getting assistance from religious leaders and creating committees at the grass roots levels comprising the key opinion leaders, clerics, and trained health professionals/physicians, with the aim of reducing myths and misconceptions locally as their communication technique, is well perceived by the community. Importantly, continuity should be the key priority of any initiative. Hence, sustainability can be achieved by linking all local initiatives to local service providers through the opinion leaders to ensure ongoing support.

Several studies from Pakistan have documented interventions such as involving and engaging religious leaders in FP programs, and encouraging the efforts of community leaders and community-based health professionals may assist in building capacity of understanding of, and cooperation on, issues of FP and childbirth and achieve improvements in contraceptive prevalence.47 Another study conducted in Pakistan described how interventions ought to be designed to address religious misconceptions and sociocultural barriers toward appropriate and just utilization of health services.24 In a different study, authors Qureshi and Shaikh document that to remove the myths and misconceptions (either sociocultural or religious) of reproductive health, education and counselling must be the basic component of every FP program. The education component of the FP program should focus on religious leaders to promote advocacy concerning health promotion and reproductive health. This same study reported the importance of coalition and forming a work team such as a “committee” between community leaders, religious leaders, and trained health professionals, with the aim of reducing myths and misconceptions locally, as their communication technique is well perceived by the community. The authors also identified trained medical doctors as an organized source of validating information and clarifying myths and misconception in a community. Moreover, the local clerics or Imams in a community can provide advocacy to people on such issues from their channel by highlighting the advantages. This can not only clarify but help to eradiate myths related to FP.

In order to improve contraceptive use in Pakistan, more emphasis must be placed on educating couples regarding contraceptive services and on strengthening the perceptions of different groups of opinion leaders, especially religious leaders, that religion not only allows but also recommends FP. Ex-President of Pakistan Mr Pervez Musharraf said that population growth was “the main factor retarding economic growth, poverty alleviation, and action on joblessness.”48 Pakistan’s per capita income would be much higher today, Musharraf also stated, if its population had grown at 2% instead of 3% annually between 1951 and the 1980s. Pakistan’s population more than quadrupled in size between 1950 and 2005.

Finally, strengthening perceptions also means creating awareness among women of their reproductive health rights and among the communities in general about the size of their family in the light of prevailing economic conditions in the country.

Limitations of the study

Due to the lack of research conducted with opinion leaders on this topic, it is difficult to estimate how generalized the findings are to broader contexts. Findings should be considered as an insight into the diversity of the experiences and perspectives. A further limitation of the study was that the population sample was limited to male opinion leaders who were able to read, write, and speak Urdu, as no female community leader was identified in the target community, which is somewhat a reflection of the social codes that the study identifies, although the configuration of opinion leaders and primary language spoken within the target community may vary. The health professionals/physicians from the sample were homeopathic doctors. No trained medical doctor could be located in the target area. This could have had an impact on the range of perspectives presented. Such limitations can be overcome in future studies where researchers can seek to assess similar opinions among women health providers as well as those who do not speak Urdu and are more well versed with other local languages.

Acknowledgments

First, the author is greatly indebted to Dr Graham Brown, Senior Lecturer, Western Australian Centre for Health Promotion Research, Health Sciences, School of Public Health, Curtin University, WA, Australia, for being a supervisor and mentor and for his continuous efforts, which contributed to the completion of this manuscript and research study. The author is extremely thankful to Dr Babar Tasneem Shaikh, Associate Professor at the Health Services Academy Islamabad, and Dr Omar Farooq Khan for his expert and overwhelming support in editing the draft of this manuscript with patience. The author is also grateful to the opinion leaders who participated in this study, and to Mr David Packer, Dr Abdul Basher, and Dr Wahid Shah Buneri for support. Finally, the author is grateful to the Australian Agency for International Development and to the School of Public Health, Curtin University of Technology, for providing partial funding for this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work. The author alone is responsible for the content and the writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Hakim A. Fertility trends and their determinants in Pakistan. In: Jones WJ, Karim MS, editors. Islam, The State and Population. 2nd ed. UK: C Hurst and Co. Ltd; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ertem M, Ergenekon P, Elmaci N, Ilcin E. Family planning in grand multiparous women in Diyarbakir, Turkey, 1998: the factors affecting contraceptive use and choice of method. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2001;6(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kridli SA, Libbus K. Contraception in Jordan: a cultural and religious perspective. Int Nurs Rev. 2001;48(3):144–151. doi: 10.1046/j.1466-7657.2001.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schenker JG. Women’s reproductive health: monotheistic religious perspectives. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2000;70(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)00225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The World Fact Book. 2011. [Accessed November 15, 2011]. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2122.html#pk.

- 6.UNDP. Human development report. United NationsDevelopment Program; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishtar S. Reforming Pakistan’s mixed health system Choaked Pipes. Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford University Press; 2010. p. 311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans DB, Edejer TT-T, Adam T, Lim SS for the WHO. Choosing Interventions that are Cost Effective (CHOICE) Millennium Development Goals Team. Methods to assess the costs and health effects of interventions for improving health in developing countries. BMJ. 2005;331(7525):1137–1140. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7525.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hogan MC, Foreman KJ, Naghavi Mohsen, et al. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980–2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet. 2010;375(9726):1606–1623. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60518-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alam AY. Health equity, quality of care and community based approaches are key to maternal and child survival in Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61(1):1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO. Research on reproductive health at WHO. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO. The world health report 2005 Make every child and mother count. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF. Maternal mortality in 2000: estimates developed by World Health Organization. United Nations Children’s Fund and United Nations Population Fund; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute of Population Studies, Macro International. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2006–2007. Islamabad, Packistan: Government of Pakistan; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sathar Z, Singh S, Fikree FF. Estimating the incidence of abortion in Pakistan. Stud Fam Plann. 2007;38(1):11–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2007.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.AbouZahr C. Global burden of maternal death and disability. British Medical Bulletin. 2003;67(1):1–11. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell OMR, Graham WJ. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. The Lancet. 2006;398:1284–1299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casterline JB, Sathar ZA, Haque M. Obstacles to Contraceptive Use in Pakistan: A Study in Punjab. Stud Fam Plann. 2001;32(2):95–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douthwaite M, Ward P. Increasing contraceptive use in rural Pakistan: an evaluation of the Lady Health Worker Program. Health Policy Plan. 2005;20(2):117–123. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czi014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghuman SJ, Helen J, Lee HJ, Smith HL. Measurement of womens’ autonomy according to women and their husbands: results from five Asian countries. Soc Sci Res. 2006;35:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mumtaz Z, Salway S. ‘I never go anywhere’: extricating the links between women’s mobility and uptake of reproductive health services in Pakistan. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1751–1765. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saleem S, Bobak M. Women’s autonomy, education and contraception use in Pakistan: a national study. Reprod Health. 2005;2(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali M, Ushijima H. Perceptions of men on role of religious leaders in reproductive health issues in rural Pakistan. J Biosoc Sci. 2005;37:115–122. doi: 10.1017/s0021932003006473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stephenson R, Hennink M. Barriers to family planning service use among the urban poor in Pakistan. Asia Pac Popul J. 2004;19(2):5–26. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zafar I, Asif F, Adil S. Religiosity as a factor of fertility and contraceptive behaviour in Pakistan. J Appl Sci. 2003;3(3):158–166. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaikh BT. Unmet need for family planning in Pakistan – PDHS 2006–2007: it’s time to re-examine déjà vu. Open Access Journal of Contraception. 2010;1:113–118. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hakim A. Factors affecting fertility in Pakistan. The Pak Dev Rev. 1994;33(2):685–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karim MS, Mahmood MA. Health systems in Pakistan: a descriptive analysis. Karachi, Pakistan: Department of Community Health Sciences, Aga Khan University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qureshi N, Shaikh BT. Myths, fallacies and misconceptions: applying social marketing for promoting appropriate health seeking behavior in Pakistan. Anthropol Med. 2006;13(2):131–139. doi: 10.1080/13648470600738716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaikh I, Omair A, Inam SNB, Safdar S, Kazmi T, Anjum Q. National Polio Day campaign in a squatter settlement through medical students. J Pak Med Asso. 2003;53(3):98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siddiqui H, Qudsia A, Omair A, Usman J, Rizvi R, Ashfaq T. Risk factors assessment for hypertension in a squatter settlement of Karachi. J Pak Med Asso. 2005;55:390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strauss A, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nasir JA, Tahir MH, Zaidi AA. Contraceptive attitude and behaviour among university men: a study from Punjab, Pakistan. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2010;22(1):125–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.International Planned Parenthood Federation. Death and denial: unsafe abortion and poverty. London, UK: IPPF; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pasha O, Fikree FF, Vermund S. Determinants of unmet need for family planning in squatter settlements in Karachi, Pakistan. Asia Pac Popul J. 2001;16(2):93–108. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ali Q. Policy advocacy: a framework for social change in pakistan. Islamabad, Pakistan: Leadership for Environment and Development (LEAD); 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 37.El Wardini E. Initiatives and resistances in the Arab states. Int Rev Educ. 1993;39(1–2):113–118. doi: 10.1007/BF01102451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoodfar H, Assadpour S. The politics of population policy in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Stud Fam Plann. 2000;31:19–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2000.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vahidnia F. Case study: fertility decline in Iran. Population Environment. 2007;28:259. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schoemaker J. Contraceptive use among the poor in Indonesia. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2005;31(3):106. doi: 10.1363/3110605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Underwood C. Islamic precepts and family planning: the perceptions of Jordanian religious leaders and their constituents. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2000;26(3):110–117+136. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shah MA, Shah NM, Chowdhury RI, Menon I. Unmet need for contraception in Kuwait: issues for health care providers. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:1573–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ali M, Bhatti MA, Ushijima H. Reproductive health needs of adolescent males in rural Pakistan: an exploratory study. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2004;204(1):17–25. doi: 10.1620/tjem.204.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ali M, Rizwan H, Ushijima H. Men and reproductive health in rural Pakistan: the case for increased male participation. Eur J of Cont Repro Healthcare. 2004;9:260–266. doi: 10.1080/13625180400017511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khawaja NP, Tayyeb R, Malik N. Awareness and practices of contraception among Pakistani women attending a tertiary care hospital. J Gyn Obst. 2004;24(5):564–567. doi: 10.1080/01443610410001722662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MOPW. Islamabad Declaration on Population and Development (IDPD) issued by International Ulama Conference. Paper presented at: International Ulama Conference 2006; Islamabad, Pakistan. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fikree FF, Khan A, Kadir MM, Sajan F, Rahbar MH. What influences contraceptive use among young women in urban squatter settlements of Karachi, Pakistan. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2001;27(3):130. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pervez M. The president of Pakistan on the need to slow population growth in the Muslim world. Popul Dev Rev. 2005;31(2):399. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh S, Wulf D, Hussain R, Bankole A, Sedgh G. Abortion worldwide: a decade of uneven progress. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 50.United Nations. World abortion policies. Department of Economics and Social Affairs, Population Affairs; 2011. [Google Scholar]