Abstract

The design of novel integrase (IN) inhibitors has been aided by recent crystal structures revealing the binding mode of these compounds with a full-length prototype foamy virus (PFV) IN and synthetic viral DNA ends. Earlier docking studies relied on incomplete structures and did not include the contribution of the viral DNA to inhibitor binding. Using the structure of PFV IN as the starting point, we generated a model of the corresponding HIV-1 complex and developed a molecular dynamics (MD)-based approach that correlates with the in vitro activities of novel compounds. Four well-characterized compounds (raltegravir, elvitegravir, MK-0536, and dolutegravir) were used as a training set, and the data for their in vitro activity against the Y143R, N155H, and G140S/Q148H mutants were used in addition to the wild-type (WT) IN data. Three additional compounds were docked into the IN-DNA complex model and subjected to MD simulations. All three gave interaction potentials within 1 standard deviation of values estimated from the training set, and the most active compound was identified. Additional MD analysis of the raltegravir- and dolutegravir-bound complexes gave internal and interaction energy values that closely match the experimental binding energy of a compound related to raltegravir that has similar activity. These approaches can be used to gain a deeper understanding of the interactions of the inhibitors with the HIV-1 intasome and to identify promising scaffolds for novel integrase inhibitors, in particular, compounds that retain activity against a range of drug-resistant mutants, making it possible to streamline synthesis and testing.

INTRODUCTION

Retroviruses are distinguished by their ability to reverse transcribe a single-stranded RNA genome into a linear double-stranded DNA. The viral integrase (IN) then inserts this linear viral DNA into the genome of the target cell to establish a stable infection. Integration catalyzed by IN follows two distinct steps (51). First, IN cleaves a GT dinucleotide from the 3′ end of both strands of the viral DNA (3′ processing [3′-P]). This leaves a conserved CA sequence with a free hydroxyl on each of the 3′ ends of the viral DNA and a 2-nucleotide overhang on each of the 5′ ends. In the second reaction, IN uses the newly created 3′ hydroxyl to attack the phosphodiester backbone of the host genome (strand transfer [ST]). Depending on the retrovirus, the two viral ends are inserted 4 to 6 bases apart, creating a small duplication in the target DNA flanking the provirus (5 nucleotides in the case of HIV-1 and 4 for prototype foamy virus [PFV]) (50). Cellular enzymes repair the gaps, leaving the double-stranded proviral DNA stably integrated into the genome of the infected cell.

Integrases consist of three functionally distinct domains that have been characterized by biochemical and mutational analyses. The N-terminal domain (NTD; residues 1 to 50) contains a zinc-binding HHCC motif and contributes to multimer formation (7, 8). The C-terminal domain (CTD; identified as residues 212 to 288 in deletion studies) nonspecifically binds DNA (18, 20, 34, 42). The catalytic core domain (CCD; residues 50 to 212) contains the catalytic triad DD35E motif that is well conserved among the retroviral integrase superfamily (7, 11, 19, 32). This active site coordinates two metal ions and binds one viral DNA end. Although IN complexes exist in solution in different multimeric states, recent crystallographic data confirmed that the functional intasome is a tetrameric protein, with the two inner INs forming a head-to-tail dimer (catalytically active monomers). This arrangement allows all three domains of each of the inner subunits to participate in multimerization and DNA binding. Each of the inner INs also forms a head-to-head dimer with an outer IN (structural monomers), forming the tetramer seen in the complete intasome (14). The outer INs presumably function to stabilize the inner head-to-tail dimer or help it to interact with cellular factors or target DNA (27, 33).

Integration is an established target for antiretrovirals. Clinically relevant IN inhibitors show selectivity for the ST reaction and only weakly inhibit 3′ processing (45). These compounds are referred to as IN strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs). Raltegravir (RAL) is the only INSTI to be approved by the FDA. Elvitegravir (EVG) and dolutegravir (DTG; S/GSK1349572) are in advanced clinical trials (48), and additional INSTIs are in earlier stages of development (Fig. 1). A refined crystal structure of full-length HIV-1 IN remains elusive, and this has hindered development of novel INSTIs. Individual domains have been solved by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (8, 9, 18, 40) and crystallography (6, 12, 13, 17, 18, 24–26, 44, 55), but these partial structures provided little insight into the overall architecture of the intasome. Several two-domain structures were also solved (12, 54). These structures showed numerous potential dimer interfaces and linker orientations, and a flexible loop near the active site precludes high-resolution diffraction in this critical region. The CCD of HIV-1 IN has also been crystallized in a complex with the IN binding domain (IBD) of the cellular transcription factor lens epithelium-derived growth factor (LEDGF) (15). The crystal structure of an HIV-2 IN-IBD complex shows contacts between LEDGF and both the NTD and CCD of IN (13, 15, 29). However, the most serious problem was that none of the complexes contain either viral or host DNA.

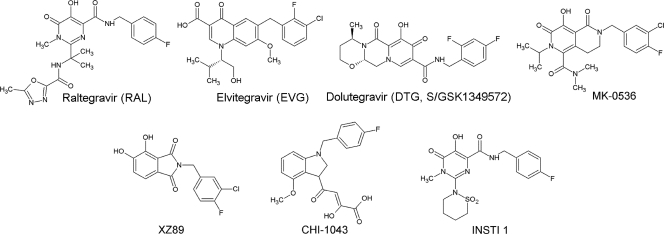

Fig 1.

Integrase inhibitors. Raltegravir received FDA approval in 2007, while elvitegravir and dolutegravir are currently in advanced clinical trials. MK-0536, XZ89, CHI-1043, and INSTI 1 have been reported in the literature but are currently not in clinical trials.

The recently solved crystal structures of the prototype foamy virus (PFV) intasome containing viral DNA, and in some cases host DNA as well, not only reveal the architecture of the intasome and binding mode of INSTIs but also have clarified the mechanism(s) of resistance to INSTIs that underlies selected mutations (28, 31, 43). INSTIs interact with the intasome in two distinct ways; they bind the two Mg2+ ions in the active site and they displace the terminal adenosine of the integrating DNA strand, allowing a halobenzyl moiety to stack with the base of the penultimate cytosine (28). Kinetic data indicate a two-step binding mechanism (22, 37), suggesting that Mg2+ binding and cytosine stacking could be decoupled and proceed at different rates. These structures are particularly exciting because they reveal that INSTIs interact extensively with highly conserved elements in and around the active site and that INSTI binding may require less direct protein contact than do those of other types of anti-HIV drugs.

As with all classes of antiretrovirals developed thus far, resistance mutations that reduce the efficacy of the INSTIs have emerged. Substitutions at positions Y143, Q148, and N155 in HIV-1 IN confer resistance to RAL (48). Although these mutations affect the fitness of the virus, secondary mutations that improve viral fitness can be selected (10, 38). Mutations at Y143 eliminate a π-stacking interaction with the oxadiazole ring, which is present in RAL but not in most other INSTIs; this mutant is effectively inhibited by INSTIs whose binding does not rely on contact with Y143 (49). Mutations at position Q148 are often accompanied by a secondary mutation at position G140. The G140S/Q148H double mutant forms a hydrogen bond network across the flexible loop of IN (31); these mutations reduce the susceptibility of IN to both RAL and EVG (47), while susceptibility to MK-0536 and DTG is only modestly affected (30, 46). N155 is positioned such that it makes Van der Waals contacts with both D64 and E152 of the catalytic triad and likely reduces susceptibility to RAL and EVG by altering the binding geometry around the Mg2+ ions (Fig. 2). As with the G140S/Q148H IN, MK-0536 and DTG retain activity against N155H. Even though this set of resistance mutations is limited, the effects of these mutations on susceptibility to these four compounds are distinct. This illustrates the importance of developing accurate methods for predicting the antiviral activity of INSTIs against both wild-type (WT) and drug-resistant forms of HIV-1 IN.

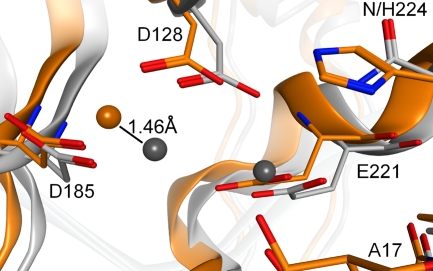

Fig 2.

Mn2+ displacement by the N224H mutation in uninhibited PFV IN. The PFV IN N224H mutant is analogous to the HIV-1 IN N155H mutant. Crystal structures of the WT and N224H PFV intasomes have been determined (PDB IDs 3OY9 and 3OYM, respectively) (28, 31). Directly overlaying the two structures shows that the Mn2+ ion bound by D128 and D185 (analogous to D64 and D116 in HIV-1 IN) shifts by 1.46 Å in the presence of the N224H mutation. The Mn2+ ion bound by D128 and E152 (D64 and E152 in HIV-1) is resolved in the crystal structure of WT PFV IN but not in the mutant structure. The side chain oxygens of D128 and E221 all shift between 1.15 and 1.17 Å, while the binding side chain oxygen of D185 shifts 0.63 Å. The 3′ hydroxyl of the terminal adenosine (A17) also shifts 0.87 Å. With a single mutation causing so many shifts around the active site, INSTIs must be able to make specific interactions and yet incorporate enough flexibility to overcome these perturbations.

The development of early INSTIs was driven by structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies and in silico screening based on structures of fragments of HIV-1 IN (3, 39, 41, 52). The recent crystal structures of PFV IN-DNA-INSTI complexes have provided valuable new insights into the binding modes of the inhibitors. Using the PFV IN structures, we developed a homology model of HIV-1 IN with similarities to that of Krishnan et al. (36). This is one of two recently published models that rely on structures of HIV-1 IN fragments to develop a full-length model (23, 36). The available HIV-1 IN fragment structures differ in the arrangement of interdomain linkers and dimer interfaces. Our model was built using the crystal structure of full-length PFV IN and the available structures of the HIV-1 fragments; however, in our model the structure of the interdomain linkers is based on the PFV IN structure. We have used our model in a docking and molecular dynamics (MD) protocol that correlates the interaction potential of the Mg2+ ions in several INSTI-intasome complexes with their in vitro activities. This correlation includes the RAL-resistant mutants Y143R, N155H, and G140S/Q148H. Additional mutants can be easily incorporated into the analysis. This is important because, when INSTIs under investigation are approved for clinical use, therapy with these new INSTIs will select for new resistance mutations, in addition to those seen with RAL treatment. We also present a series of binding energy calculations that can be applied to examine changes in activity between compounds or between mutants. Energy differences can be calculated for the internal or interaction potential for the ligand, Mg2+ ions, protein residues, and the DNA's terminal dinucleotide. These approaches can significantly reduce the amount of chemical synthesis needed to develop new INSTIs by identifying compounds predicted to have weak activity and focusing synthesis on compounds with favorable thermodynamic profiles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Docking INSTIs.

The coordinates of our HIV-1 IN model are based on the PFV IN crystal structure that served as the initial template (Protein Data Bank [PDB] identification [ID] 3L2T). The sequences of the HIV-1 and PFV IN catalytic core domains were aligned with an array of other retroviral integrases. Using the CCD alignment as a starting point, sequence alignments were performed for the NTD and CTD. A homology model was generated using MOE 2009.10 (Chemical Computing Group, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) based on the full-length alignment, and energy was minimized with the AMBER99 force field with relative field solvation, as recommended by the manufacturer (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Side chains of conserved residues were used as initial conformations of side chains in the model, while only backbone heavy atoms were conserved between nonidentical residues. Side chain conformations were sampled from a rotamer library. Backbone geometry of insertions and deletions was modeled after searching the PDB for high-resolution structures of similar chains. The CCD of the structural subunit, viral DNA end, RAL, and solvent molecules were kept in place and used as templates during the energy minimization. The process was repeated for the structural subunit, including only those residues that resolved in the crystal structure.

Because the homology model included coordinates for RAL from the corresponding PFV IN crystal structure, RAL and other INSTIs that have been cocrystallized with the PFV intasome and whose structures are available could be directly placed into the binding site of our HIV-1 model. Five water molecules in the immediate vicinity of the active site were kept explicit, and the rest were removed before placing the compound. These water molecules make direct contacts with either the inhibitor or the Mg2+ ions. Following placement, a 10-layer spherical water soak was performed, centered on the INSTI. When we tried to do the initial minimizations using AMBER99, the stacking between the halobenzyl ring and the penultimate cytosine base was distorted. Therefore, the entire structure with a solvated INSTI binding site was energy minimized to a root mean square (RMS) gradient of 0.01 using the CHARMM27 force field (5) and explicit water molecules in a TIP3P water model. Residues within 8.0 Å of the ligand were minimized again to an RMS gradient of 0.5 using the MMFF94x force field incorporated into MOE. The resulting structures served as the initial states for molecular dynamics simulations.

Inhibitors for which there were no crystallographic data were docked in the binding pocket using a model of the HIV-1 intasome complex with a structurally similar compound as a template. The same five active-site water molecules described above were retained in these dockings. Ligands were placed using the Triangle Matcher function in MOE and scored using the London dG function. Resulting ligand poses were subjected to refinement using the MMFF94x force field without side chain tethering and rescored using the Affinity dG function. All scoring and refinement functions are included in MOE2009.10. These functions did not always result in the expected ligand pose producing the best score but increased the likelihood that such a pose would be among the best scores. The output poses were screened for the expected Mg2+ binding and π-stacking with the base of the cytosine near the 3′ end of the integrating DNA strand. The ligand pose closest to the template conformation in these respects was selected regardless of whether other poses yielded better docking scores. These docked complexes were then treated as described above in terms of solvation and energy minimization and then used for molecular dynamics simulations.

RAL and DTG binding energy calculations.

MD simulations were used to determine both the internal and interaction potentials for each component of the INSTI-intasome interaction. All simulations were run using MOE 2009.10. The RAL-bound model was stripped of all but the five active-site water molecules. A 12-layer water soak was then built around all atoms of the inhibitor, the metal ions, the terminal DNA dinucleotide, and IN residues near the active site (residues 62 to 66, 114 to 120, and 138 to 154). This solvated structure was energy minimized using the AMBER99 force field with the distance-dependent dielectric electrostatics function. Each simulation began at, and equilibrated to, 310 K for 100 ps with a time step of 0.002 ps. The NPT ensemble and NPA algorithms were employed (4).

A total of 8 sets of simulations were run in duplicate for each calculation (16 simulations per calculation). Internal and interaction energies were separately calculated for the following components of the inhibitor-bound complex: the IN residues listed above, DNA residues C16 and A17, the Mg2+ ions, and the inhibitor. Energy calculations for each of these four atoms sets were run in duplicate, requiring 8 total simulations. The same calculations were performed for the IN residues, the dinucleotide, and Mg2+ ions in the uninhibited complex. In this uninhibited model, the terminal adenosine that is displaced by INSTI binding is in the conformation required for strand transfer with its 3′-OH bound to the Mg2+ ion (labeled Mg b in Fig. 3). Using just the coordinates of the inhibitor from the RAL-IN-DNA complex, a 10-layer water shell was generated around the ligand and energy minimized, as described for the complex, using the MMFF94x force field. In the INSTI-bound intasome model, the 12-layer water soak covers all of the atoms (protein, DNA, and ligand) included in energy calculations. For the unbound ligand, a 10-layer water soak was sufficient to cover all the atoms in the calculation. MD simulations for energy calculations of the protein and DNA were run using AMBER99, while simulations for energy calculations of the ligand and Mg2+ ions were run using MMFF94x. The length of all simulations was 100 ps with a time step of 0.002 ps. Initial and final temperatures were 310 K. All water molecules from the soaks described above were kept explicit, and their bonds were held rigid. Internal and interaction potentials of each set of atoms were recorded every 0.5 ps. The first 50.0 ps was treated as an equilibration period and not included in calculations, while the mean and standard deviation of both the internal and interaction potentials were calculated for the remaining 100 time points (50.5 to 100 ps). The differences between the uninhibited and inhibited complexes gave the energy change of each component of the complex during the transition from the unbound-INSTI to bound-INSTI states. Each simulation gave 100 values each for internal energy, interaction energy, and total energy (the sum of internal and interaction energies), and mean values were calculated for each simulation. Each value reported here is the mean of the means of the duplicate simulations.

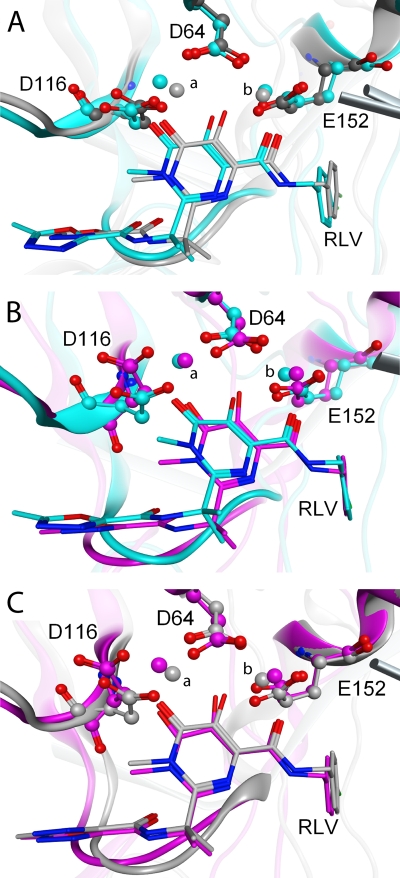

Fig 3.

Pairwise overlays of the IN catalytic triad. (A) Heavy atoms in the catalytic DDE residues of the 3L2T PFV IN-RAL crystal structure (gray) and our model (cyan) overlay with an RMSD of 0.46 Å, while Mg2+ ions a and b differ by 0.86 and 0.31 Å, respectively. (B) Overlaying the same atoms from our model (cyan) and the Krishnan et al. model (magenta) (36) gives an RMSD of 1.45 Å, with Mg ions a and b shifting 0.39 and 0.67 Å, respectively. (C) The RMSD of these residues between the Krishnan et al. model (magenta) and PFV crystal structure (gray) is 1.35 Å, with Mg2+ ions a and b shifting 0.64 and 0.59 Å. Given that the resolution of the crystal structure is 2.85 Å, these values show that the active sites of the three structures are quite similar (28).

Determining Mg2+ interaction potentials.

MD simulations were performed using the MMFF94x force field parameters, NPT ensemble, and NPA algorithms with a starting and equilibrated temperature of 310 K (4). As a reference, the two magnesium ions from our WT-RAL model were stripped of surrounding protein, DNA, and inhibitor and solvated as described above. The interaction potential for these solvated Mg2+ ions was determined using this MD approach. Hydration of Mg2+ ions has been studied using more exhaustive molecular dynamics approaches, and the solvation energies have been reported to be in the range of −431.1 to −435.4 kcal/mol (1, 35, 53). Our approach calculated the solvation energy of a single Mg2+ ion to be −444.7 kcal/mol. Our intention was to develop an approach that could be used to rapidly calculate energies that correlate INSTI activity. Although this hydration energy value differs somewhat from published values, the reduced computational requirement made this approach attractive. Interaction potentials reported here are the difference between those of Mg2+ ions in the HIV-1 IN-DNA-INSTI complex and this solvated reference. Units for the reported values are kcal/mol.

Mutants were generated by overlaying our model with the crystal structures of S217H and N224H PFV IN (PDB IDs 3OYK and 3OYM, respectively). These mutants correspond to Q148H and N155H in HIV-1 IN. The position in PFV IN that corresponds to the site of the G140S mutation that appears in HIV-1 INs carrying the Q148H mutation is already a serine in wild-type PFV IN. The coordinates for these residues from the crystal structures replaced those of the wild-type residue in our HIV-1 IN model. Ligands were placed in the mutant INs using coordinates from the wild-type models. Solvation and energy minimization were performed as described for docked INSTIs.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Verification of the HIV-1 IN model.

Overlaying our HIV-1 IN model with the PFV IN crystal structure or with the Krishnan et al. model (36) shows strong similarity in the INSTI binding region (Fig. 3). D64 and E152 superimpose particularly well. The position of the Mg2+-binding Oδ atom of D116 differs by 1.79 Å between the two HIV-1 IN models. There is a corresponding shift in water molecules around the Mg2+ ion to maintain the geometry of the binding site. Additional residues around the INSTI binding pocket, particularly Y143 and P145, show only minimal differences between the HIV-1 IN models (not shown). Similar displacements of the terminal adenosine (A17 in the crystal structure) are seen in the two models, and the base of C16 is positioned to stack with the halobenzyl ring of RAL. There are discrepancies between the two models, particularly with the arrangement of the CTD and intersubunit contacts at the head-to-head dimer interface (between one inner monomer and its outer counterpart). Mutagenesis experiments that should help to elucidate the structural features of the HIV-1 intasome are under way.

Docking and MD simulations.

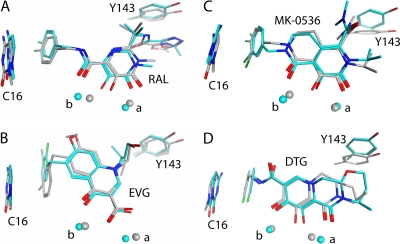

Available crystal structures provide a valuable tool for validating our docking protocol. Docked structures of RAL, EVG, MK-0536, and DTG are shown in Fig. 4 with the corresponding coordinates of the inhibitor from the PFV IN-bound crystal structures. All compounds superimpose well. The heavy atom root mean square deviation (RMSD) between the two structures for EVG is slightly higher than those for RAL and MK-0536 due to a rotation of the halobenzyl moiety. The RMSD of DTG between the crystal structure and the model is elevated because the three rings are closer to a planar conformation in the model, while the ring closest to Y143 is bent sharply out of the plane of the other two rings in the crystal structure.

Fig 4.

Overlays of inhibitors from HIV-1 models (cyan) and PFV crystal structures (gray). For all panels, magnesium ion a is bound by the side chains of residues D64 and D116 in HIV-1 IN and residues D128 and D185 in PFV IN, while magnesium ion b is bound by residues D64 and E152 in HIV-1 IN and residues D128 and E221 in PFV IN. Heavy atom RMSD values for each compound are as follows: RAL, 0.88 Å (A); EVG, 1.51 Å (B); MK-0536, 1.10 Å (C); DTG, 1.30 Å (D).

Generating docked structures that accurately reflect the actual structures of bound ligands is critical to the accuracy of the MD simulations. While minor discrepancies can be eliminated during the equilibration phase of the MD simulations, docked structures that cannot reach their biologically relevant conformation during that time will result in erroneous interaction potentials. In the absence of crystallographic data, docked structures that show strong correlations with in vitro activity are more likely to reflect the actual structures. The in vitro susceptibility data for WT IN and drug-resistant mutants for RAL, EVG, MK-0536, and DTG correlate well with the calculations. The corresponding in vitro data for XZ89, CHI-1043, and INSTI 1 against drug-resistant IN mutants are not available.

Crystal structures and static models provide a snapshot of what is taking place in a molecular system. Basing an energy calculation on a single structure raises the possibility of error due to relatively minor discrepancies in the structure. Our calculations each include data for 100 similar variations resulting from the bond rotation and oscillation introduced by the MD simulation. This should compensate for two potential sources of error. First, side chains or entire secondary structure elements could be influenced by crystal packing contacts. Second, crystal packing could directly influence the orientation of the ligand or cause indirect influence via contacts with a neighboring protein residue. Either of these cases could perturb the interaction and introduce error into the calculation. Monitoring the results of Hamiltonian equations through the simulation shows that the system is sufficiently equilibrated after 50.0 ps (not shown), and averaging the 100 instantaneous interaction potential values obtained after that time point gives a result that closely correlates with the in vitro activity of the compounds.

Calculating the binding energy of RAL and DTG.

The total binding energy of a ligand-substrate interaction can be viewed as the sum of the energy change of the ligand and the energy change of the substrate. INSTI binding is complicated by the interactions with the Mg2+ ions and the end of the viral DNA. The equation for INSTI binding energy is ΔEbinding = ΔEligand + ΔEDNA + ΔEprotein + ΔEMg. For each reactant, E is the sum of individual factors: ΔEtotal = ΔEinternal + ΔEinteraction. These factors can be further broken down: ΔEinternal = ΔEangle + ΔEstretching + ΔEstrain. Here, internal energy is the sum of the energy change associated with changes in bond angles, bond distances, and the strain resulting from intramolecular Van der Waals contacts. For interaction energy changes, the equation is ΔEinteraction = ΔEH-bonding + ΔEVdW + ΔEelectrostatic. Hydrogen bonding, Van der Waals contacts, and electrostatic effects were the only intermolecular forces taken into consideration in these calculations. Internal and interaction energies were calculated for specific atoms of each component using separate MD simulations. The ΔEligand calculations included all ligand atoms. Calculations of ΔEDNA included all atoms of the C16 and A17 residues. All atoms of residues 62 to 66, 114 to 120, and 138 to 154 of the catalytic subunit of HIV-1 IN were included in the ΔEprotein calculations. Both active-site ions were used for the ΔEMg calculations. Figure 5A shows the locations of the atoms of all four reactants in the WT HIV-1 IN model.

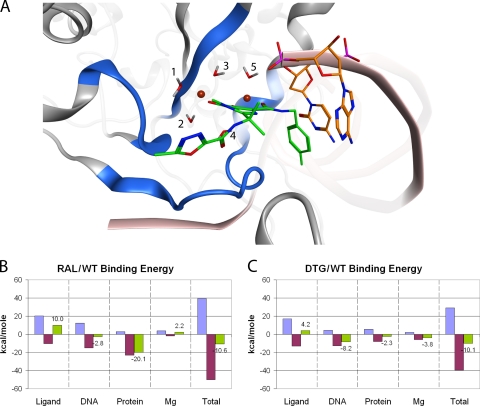

Fig 5.

Binding energy calculations for RAL and WT HIV-1 IN. (A) Only the highlighted residues were included in the binding energy calculations. Protein residues 62 to 66, 114 to 120, and 138 to 154 are shown as blue ribbons; DNA residues C16 and A17 are shown as sticks with orange carbon atoms; the Mg2+ ions are brown; and RAL is shown as sticks with green carbon atoms. The water molecules were held constant throughout the modeling and are shown as stick representations and labeled 1 to 5. (B) For each reactant, ΔEinternal (blue), ΔEinteraction (magenta), and ΔEtotal (green) were calculated from MD simulations. Total binding energy was the sum of each component from the four reactants. These data indicate that the preference of the protein for the RAL-bound state is the predominant factor in RAL binding and that the drug itself prefers an aqueous environment. (C) The same sets of calculations performed for RAL were also done for DTG. For DTG, the preference of the ligand for the aqueous state was weaker, the DNA had a stronger preference for the DTG-bound state, the protein favored the DTG-bound state to a lesser degree than the RAL-bound state, and the Mg2+ ions had a greater preference for the DTG-bound state.

The WT binding energy calculations for RAL are summarized in Fig. 5B. For all reactants, negative values are favorable and positive values are unfavorable. An interesting observation is that the overall ΔEligand is unfavorable. While the interaction energy is negative, the internal energy is positive and of greater magnitude. This does not indicate that the reaction as a whole is energetically unfavorable but rather that RAL prefers the relative freedom of an aqueous environment to the constrained binding pocket of the intasome. However, the overall ΔEprotein is favorable and of greater magnitude than the ΔEligand. This suggests that when RAL is bound, the interaction of the protein with the drug, the Mg2+ ions, and the terminal dinucleotide is more favorable than the interaction of the protein with the Mg2+ ions and DNA in its catalytically active conformation in an aqueous environment. The preference of the protein for the RAL-bound state is greater than the preference of RAL for the aqueous state; thus, the reaction favors the RAL-bound state. By comparison, the energy contributions of the terminal DNA residues and the Mg2+ ions are relatively small and nearly negate each other. This will be discussed in more detail below. The apparent Kd (dissociation constant), measured as the ratio of koff/kon, was determined to be 18.5 nM at 20°C for INSTI 1 (Fig. 1) using a scintillation proximity assay (37). This Kd can be inverted to give a Ka of 5.41 × 107 M−1, which can then be applied to the Gibbs-Helmholtz equation. Solving this equation for ΔG gives an experimentally derived value of −10.4 kcal/mol for INSTI 1 binding at 20°C. This is close to our calculated total value of −10.6 kcal/mol at 37°C.

Performing these simulations with the DTG-bound complex resulted in an altered energetic profile (Fig. 5C). The ΔEbinding of the ligand, DNA, and Mg2+ ions was more favorable with DTG than with RAL, while the contribution of the protein was reduced. The energy change associated with the DNA likely results from the adenine base lying flat on the ring structures of DTG (30). The conserved nature of the terminal CA dinucleotide and the observation that the DNA could make the greatest energetic contribution to DTG binding could help explain why DTG retains activity against a number of INSTI-resistant mutants (30). It should be noted that the overall ΔEbinding of RAL is 0.5 kcal/mol lower than DTG in our calculations. The in vitro 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) of RAL and DTG were reported to be 26 nM and 33 nM, respectively (30, 46). The slightly lower IC50 for RAL against WT HIV-1 IN than for DTG agrees with our calculation that the binding energy of RAL is slightly lower than that of DTG.

Specific contacts between the ligand and protein apparently influence the interactions of the Mg2+ ions with the protein, affecting the overall interaction with INSTIs. The Y143R mutant eliminates a π-stacking interaction between RAL's oxadiazole ring and the tyrosine side chain (49). Replacing the tyrosine side chain with a charged arginine would likely make the INSTI binding region of the protein more hydrophilic in addition to causing the loss of π-stacking. Both of these factors would make the ligand's and the protein's ΔEinteraction and overall ΔEbinding values less favorable. In contrast, EVG, MK-0536, and DTG do not interact with Y143, so mutations at this position should not adversely affect their interactions or their overall binding energies. Moreover, MK-0536 makes considerable Van der Waals contacts with the conserved P145 residue. Targeting such residues could help stabilize an INSTI in the presence of mutations that alter the position of the Mg2+ in the active site.

The halobenzyl ring stacking with the cytosine base provides a favorable contact for the ligand where the terminal adenosine would be positioned in the uninhibited intasome. Crystal structures show that this displaced adenosine can adopt different conformations depending on the nature of the ligand. The position may affect the intramolecular strain in the phosphodiester backbone while also altering the solvation of the adenosine base that would normally stack with the penultimate cytosine. Given the conserved nature of the CA dinucleotide, optimizing this interaction could be a significant factor in future INSTI development. The binding energy calculations described here are limited in that the displaced adenosine must be in the correct orientation to obtain accurate values. Although it is possible that the adenosine's multiple conformations mean that its interactions with the INSTIs are relatively weak, crystal structures of the PFV IN-INSTI complex would be quite helpful in refining the calculations. Fortunately, the process of obtaining PFV IN crystals (both WT and mutants that correspond to the known HIV drug-resistant mutants) is developing at a rapid pace and structures of additional interesting compounds should be available in the near future. Crystallographic data and this MD approach in an HIV-1 IN model should provide valuable new details regarding INSTI binding that could lead to the development of more effective INSTIs and novel scaffolds.

Correlation of Mg binding with INSTI activity.

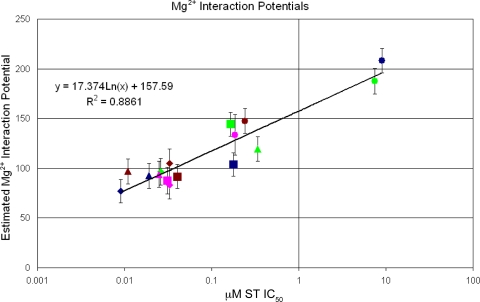

MD simulations were run for models with combinations of RAL, EVG, MK-0536, and DTG against WT, Y143R, N155H, and G140S/Q148H HIV-1 IN. Plotting the in vitro IC50s of these four compounds against their Mg2+ interaction potentials, as determined by MD simulation, results in a correlation with an R-squared value of 0.8861 (Fig. 6). These data were fitted to an exponential curve, of the form y = a[ln(x)] + b, using KaleidaGraph 4.0 (Synergy Software, Reading, PA). The formula for this curve was used to convert Mg2+ interaction potentials to estimated IC50s. Ranges of estimated IC50s were generated by adding or subtracting the standard deviation of each interaction potential from the mean value and calculating the upper and lower limits, respectively, of the estimated range. While only a limited number of data points are available at this time, this is a dynamic correlation that can change as data become available for additional compounds and mutants. At this time, compounds that perform well (i.e., IC50s less than 100 nM) are distinguishable from compounds whose IC50s exceed 1 μM, while compounds with intermediate values (i.e., between 100 nM and 1 μM) show marginal differences compared to the more potent ones.

Fig 6.

Correlation of the in vitro activity with the interaction potential. RAL (green), EVG (blue), MK-0536 (brown), and DTG (magenta) were modeled into WT (diamonds), Y143R (triangles), N155H (squares), and G140S/Q148H (circles) HIV-1 IN. MK-0536 and DTG show relatively low interaction potentials and IC50s against WT, Y143R, and N155H HIV-1 IN, with only modest increases against G140S/Q148H IN. The interaction potentials of RAL and EVG were substantially higher against the G140S/Q148H mutant, and this correlated with a corresponding loss of potency. IC50s were determined as described previously (46).

The comparatively small contribution of the Mg2+ ions to the binding energy calculations does not diminish their importance in determining the strength of the overall interaction. Figure 6 and Table 1 show that the ΔEinteraction of the Mg2+ ions can accurately estimate the in vitro activity of a novel INSTI, despite the fact that Fig. 5 shows that the Mg2+ ΔEinteraction contributes only −1.7 kcal/mol to the interaction with RAL. There are important differences in the ways in which these calculations were done that play a critical role in how the results differ. The binding energy calculations in Fig. 5 compare the differences between the ΔEinteraction values of the ions in the uninhibited intasome to those in the RAL-bound intasome. Figure 6 compares the ΔEinteraction values of two aqueous ions in the absence of protein and DNA to the energies of the ions in the full complex. In both cases, the ΔEinteraction values are influenced by the atoms that are in direct contact with the Mg2+ ions and by the forces acting on those atoms.

Table 1.

Correlation of docked compoundsa

| Compound | Predicted IC50 | Lower limit | Upper limit | Experimental IC50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XZ89 | 0.18 | 0.093 | 0.35 | 0.17 |

| CHI-1043 | 0.18 | 0.094 | 0.35 | 0.14 |

| INSTI 1 | 0.022 | 0.011 | 0.046 | 0.014 |

One hundred interaction potentials from each MD simulation were averaged, and the standard deviation was calculated. Predicted IC50s are based on the mean interaction potential. Lower and upper limits represent mean plus and minus standard deviations, respectively. The predicted IC50 of INSTI 1 is nearly an order of magnitude lower than that of XZ89 or CHI-1043, which corresponds to the reported in vitro experimental values. All three reported values fall within the range of means ± standard deviations predicted by our approach (16, 21, 56).

The binding energy calculations in Fig. 5 also include the ΔEinternal, whereas the in vitro activity correlation in Fig. 6 does not. Therefore, changes in the binding geometry will have a greater effect on the binding energy calculations than the activity correlation. The N155H and G140S/Q148H mutants appear to alter the binding geometry around the Mg2+ ions. These interactions are distance dependent, so if a mutation causes one of the Mg2+ ions to shift, the neighboring side chains and ligand must shift accordingly to compensate or the interaction potential will be altered. The free energy calculations include the ΔEinternal because these shifts may be accompanied by a change in the bond angles surrounding the Mg2+ ions.

Crystal structures of all four compounds bound to the PFV intasome have been solved (28, 30, 31). Three additional compounds were tested for which neither structural data nor activities against the mutants are available. Shown in Fig. 1, XZ89 and CHI-1043 are structurally distinct from any of the four compounds used to verify the MD approach (21, 56). INSTI 1 is similar to RAL (16). The range of the means (± standard deviations) of the interaction potentials calculated for these three compounds all overlapped our reference curve at the respective IC50s for each compound, and the most active of the three was clearly identified (Table 1). This result is particularly promising because it shows that estimated IC50s correlate with experimentally determined values even when structural data are not available.

Incorporating novel mutations into this model before crystal structures become available would be beneficial if the model can be used to determine which compounds will retain potency against these resistant mutants. Selection experiments with the INSTI MK-2048 yielded an integrase carrying the G118R mutation (2). In the model of HIV-1 IN, G118 is close to the active-site residue D116. Moreover, the Cα is oriented such that the arginine side chain would extend directly toward the D116 side chain and the magnesium ion that it binds. When this mutation is introduced into the model in silico, the arginine side chain forces the entire backbone to rotate. This would perturb a favorable Van der Waals contact between DTG and the Cα of G118 seen in the docked and crystal structures. Based on our model, the G118R mutation should increase the IC50 of DTG to 190 nM, representing nearly a 6-fold increase over the IC50 of WT IN. The in vitro activity of DTG against this mutant has not been reported, but this mutation confers an 8-fold increase in DTG's 50% effective concentration (EC50) in a single-round vector infectivity assay (30). Of the mutants selected by RAL, G140S/Q148H shows the largest reduction in susceptibility to DTG. However, DTG's in vitro IC50 for this mutant is 0.18 μM compared to 7.44 μM for RAL. The Mg2+ correlation plot estimated IC50s against this mutant to be 5.6 μM for RAL and 0.25 μM for DTG. As the newer INSTIs are approved for clinical use, additional resistance mutations will be selected, and this approach can be expanded to include the new mutants and virtually screen novel scaffolds for compounds that have broader inhibitory activity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our studies were supported by the NIH Intramural Program, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, and by NIH grants from the AIDS Intramural Targeted Program (IATAP).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 28 October 2011

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aac.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Asthagiri D, Pratt LR, Paulaitis ME, Rempe SB. 2004. Hydration structure and free energy of biomolecularly specific aqueous dications, including Zn2+ and first transition row metals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:1285–1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bar-Magen T, et al. 2010. Identification of novel mutations responsible for resistance to MK-2048, a second-generation HIV-1 integrase inhibitor. J. Virol. 84:9210–9216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barreca ML, Iraci N, De Luca L, Chimirri A. 2009. Induced-fit docking approach provides insight into the binding mode and mechanism of action of HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Chem. MedChem. 4:1446–1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bond SD, Leimkuhler BJ, Laird BB. 1999. The Nose-Poincare method for constant temperature molecular dynamics. J. Comp. Phys. 151:114–134 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brooks BR, et al. 2009. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 30:1545–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bujacz G, Alexandratos J, Qing ZL, Clement-Mella C, Wlodawer A. 1996. The catalytic domain of human immunodeficiency virus integrase: ordered active site in the F185H mutant. FEBS Lett. 398:175–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bushman FD, Engelman A, Palmer I, Wingfield P, Craigie R. 1993. Domains of the integrase protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 responsible for polynucleotidyl transfer and zinc binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:3428–3432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cai M, et al. 1998. Solution structure of the His12 → Cys mutant of the N-terminal zinc binding domain of HIV-1 integrase complexed to cadmium. Protein Sci. 7:2669–2674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cai M, et al. 1997. Solution structure of the N-terminal zinc binding domain of HIV-1 integrase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:567–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Canducci F, et al. 2010. Genotypic/phenotypic patterns of HIV-1 integrase resistance to raltegravir. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:425–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen H, Wei SQ, Engelman A. 1999. Multiple integrase functions are required to form the native structure of the human immunodeficiency virus type I intasome. J. Biol. Chem. 274:17358–17364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen JC, et al. 2000. Crystal structure of the HIV-1 integrase catalytic core and C-terminal domains: a model for viral DNA binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:8233–8238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cherepanov P, Ambrosio AL, Rahman S, Ellenberger T, Engelman A. 2005. Structural basis for the recognition between HIV-1 integrase and transcriptional coactivator p75. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:17308–17313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cherepanov P, Maertens GN, Hare S. 2011. Structural insights into the retroviral DNA integration apparatus. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 21:249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cherepanov P, et al. 2005. Solution structure of the HIV-1 integrase-binding domain in LEDGF/p75. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12:526–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dicker IB, et al. 2007. Changes to the HIV long terminal repeat and to HIV integrase differentially impact HIV integrase assembly, activity, and the binding of strand transfer inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 282:31186–31196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dyda F, et al. 1994. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of HIV-1 integrase: similarity to other polynucleotidyl transferases. Science 266:1981–1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eijkelenboom AP, et al. 1999. Refined solution structure of the C-terminal DNA-binding domain of human immunovirus-1 integrase. Proteins 36:556–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Engelman A, Bushman FD, Craigie R. 1993. Identification of discrete functional domains of HIV-1 integrase and their organization within an active multimeric complex. EMBO J. 12:3269–3275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Engelman A, Hickman AB, Craigie R. 1994. The core and carboxyl-terminal domains of the integrase protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 each contribute to nonspecific DNA binding. J. Virol. 68:5911–5917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferro S, et al. 2009. Docking studies on a new human immunodeficiency virus integrase-Mg-DNA complex: phenyl ring exploration and synthesis of 1H-benzylindole derivatives through fluorine substitutions. J. Med. Chem. 52:569–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garvey EP, et al. 2009. Potent inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase display a two-step, slow-binding inhibition mechanism which is absent in a drug-resistant T66I/M154I mutant. Biochemistry 48:1644–1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goethals O, et al. 2011. Resistance to raltegravir highlights integrase mutations at codon 148 in conferring cross-resistance to a second-generation HIV-1 integrase inhibitor. Antiviral Res. 91:167–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goldgur Y, et al. 1999. Structure of the HIV-1 integrase catalytic domain complexed with an inhibitor: a platform for antiviral drug design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:13040–13043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goldgur Y, et al. 1998. Three new structures of the core domain of HIV-1 integrase: an active site that binds magnesium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:9150–9154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Greenwald J, Le V, Butler SL, Bushman FD, Choe S. 1999. The mobility of an HIV-1 integrase active site loop is correlated with catalytic activity. Biochemistry 38:8892–8898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hare S, et al. 2009. Structural basis for functional tetramerization of lentiviral integrase. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hare S, Gupta SS, Valkov E, Engelman A, Cherepanov P. 2010. Retroviral intasome assembly and inhibition of DNA strand transfer. Nature 464:232–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hare S, et al. 2009. A novel co-crystal structure affords the design of gain-of-function lentiviral integrase mutants in the presence of modified PSIP1/LEDGF/p75. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hare S, et al. 2011. Structural and functional analyses of the second-generation integrase strand transfer inhibitor dolutegravir (S/GSK1349572). Mol. Pharmacol. 80:565–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hare S, et al. 2010. Molecular mechanisms of retroviral integrase inhibition and the evolution of viral resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:20057–20062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hickman AB, Palmer I, Engelman A, Craigie R, Wingfield P. 1994. Biophysical and enzymatic properties of the catalytic domain of HIV-1 integrase. J. Biol. Chem. 269:29279–29287 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jenkins TM, Engelman A, Ghirlando R, Craigie R. 1996. A soluble active mutant of HIV-1 integrase: involvement of both the core and carboxyl-terminal domains in multimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 271:7712–7718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jenkins TM, Esposito D, Engelman A, Craigie R. 1997. Critical contacts between HIV-1 integrase and viral DNA identified by structure-based analysis and photo-crosslinking. EMBO J. 16:6849–6859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jiao D, King C, Grossfield A, Darden TA, Ren P. 2006. Simulation of Ca2+ and Mg2+ solvation using polarizable atomic multipole potential. J. Phys. Chem. B 110:18553–18559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Krishnan L, et al. 2010. Structure-based modeling of the functional HIV-1 intasome and its inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:15910–15915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Langley DR, et al. 2008. The terminal (catalytic) adenosine of the HIV LTR controls the kinetics of binding and dissociation of HIV integrase strand transfer inhibitors. Biochemistry 47:13481–13488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee DJ, Robinson WE., Jr 2004. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) integrase: resistance to diketo acid integrase inhibitors impairs HIV-1 replication and integration and confers cross-resistance to L-chicoric acid. J. Virol. 78:5835–5847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liao C, Karki RG, Marchand C, Pommier Y, Nicklaus MC. 2007. Virtual screening application of a model of full-length HIV-1 integrase complexed with viral DNA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 17:5361–5365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lodi PJ, et al. 1995. Solution structure of the DNA binding domain of HIV-1 integrase. Biochemistry 34:9826–9833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Loizidou EZ, Zeinalipour-Yazdi CD, Christofides T, Kostrikis LG. 2009. Analysis of binding parameters of HIV-1 integrase inhibitors: correlates of drug inhibition and resistance. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17:4806–4818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lu R, Ghory HZ, Engelman A. 2005. Genetic analyses of conserved residues in the carboxyl-terminal domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase. J. Virol. 79:10356–10368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Maertens GN, Hare S, Cherepanov P. 2010. The mechanism of retroviral integration from X-ray structures of its key intermediates. Nature 468:326–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Maignan S, Guilloteau JP, Zhou-Liu Q, Clement-Mella C, Mikol V. 1998. Crystal structures of the catalytic domain of HIV-1 integrase free and complexed with its metal cofactor: high level of similarity of the active site with other viral integrases. J. Mol. Biol. 282:359–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Marchand C, Maddali K, Métifiot M, Pommier Y. 2009. HIV-1 IN inhibitors: 2010 update and perspectives. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 9:1016–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Métifiot M, et al. 2011. MK-0536 inhibits HIV-1 integrases resistant to raltegravir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:5127–5133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Métifiot M, et al. 2010. Biochemical and pharmacological analyses of HIV-1 integrase flexible loop mutants resistant to raltegravir. Biochemistry 49:3715–3722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Métifiot M, Marchand C, Maddali K, Pommier Y. 2010. Resistance to integrase inhibitors. Viruses 2:1347–1366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Métifiot M, et al. 2011. Elvitegravir overcomes resistance to raltegravir induced by integrase mutation Y143. AIDS 25:1175–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nowotny M. 2009. Retroviral integrase superfamily: the structural perspective. EMBO Rep. 10:144–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pommier Y, Johnson A, Marchand C. 2005. Integrase inhibitors to treat HIV/AIDS. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 4:236–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Savarino A. 2007. In-Silico docking of HIV-1 integrase inhibitors reveals a novel drug type acting on an enzyme/DNA reaction intermediate. Retrovirology 4:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schmid R, Miah AM, Sapunov VN. 2000. A new table of the thermodynamic quantities of ionic hydration: values and some applications (enthalpy-entropy compensation and Born radii). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2:97–102 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang JY, Ling H, Yang W, Craigie R. 2001. Structure of a two-domain fragment of HIV-1 integrase: implications for domain organization in the intact protein. EMBO J. 20:7333–7343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wielens J, et al. 2010. Crystal structure of the HIV-1 integrase core domain in complex with sucrose reveals details of an allosteric inhibitory binding site. FEBS Lett. 584:1455–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhao XZ, et al. 2009. Examination of halogen substituent effects on HIV-1 integrase inhibitors derived from 2,3-dihydro-6,7-dihydroxy-1H-isoindol-1-ones and 4,5-dihydroxy-1H-isoindole-1,3(2H)-diones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19:2714–2717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.