Abstract

Nisin U is a member of the extended nisin family of lantibiotics. Here we identify the presence of nisin U immunity gene homologues in Streptococcus infantarius subsp. infantarius BAA-102. Heterologous expression of these genes in Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris HP confers protection to nisin U and other members of the nisin family, thereby establishing that the recently identified phenomenon of resistance through immune mimicry also occurs with respect to nisin.

TEXT

Lantibiotics are antimicrobial peptides that have been the focus of intense research in recent years. These ribosomally synthesized peptides undergo posttranslational modification, resulting in the presence of unusual amino acids such as the eponymous lanthionine residues, as well as a variety of other modified residues. The nisin family is the most studied of all lantibiotics. Nisin A was initially discovered in 1928 (36, 37), and it has been used commercially as a food preservative for over 50 years (31). The nisin family has also been investigated for potential applications in clinical and veterinary settings (6, 16, 43) since it is active against a wide range of pathogens, including many drug-resistant strains (40). Indeed, it is already commercially employed as an antimastitis agent (39). To date, seven natural forms of nisin have been identified. Of these, nisin A (25), nisin Z (33), nisin Q (44), and nisin F (12) are produced by Lactococcus lactis strains, while nisin U, nisin U2, and nisin U3 are produced by Streptococcus uberis (41, 42). These variants differ from each other by as many as 11 residues across the 31- to 34-amino-acid peptides (17). The large differences between the three nisin U's and the other nisins is so significant that it could be argued that they are not, in fact, nisin variants but rather members of a distinct lantibiotic subfamily (35). As is the case with all lantibiotics, nisin producers possess immunity mechanisms which provide protection from autolethality. Despite the diversity of these peptides, the phenomenon of cross-immunity has been observed in some instances. For example, nisin U-producing strains are immune to nisins U, A, and Z (42). Similarly, the nisin A-producing strain is protected from the activity of nisin U (42). Lantibiotic immunity is provided by one or more systems consisting of a dedicated immunity peptide, LanI, or an ABC transporter which pumps the lantibiotic out of the cell, designated LanFE(G). A third immunity protein, LanH, is also present in some cases and acts as an accessory protein to the ABC transporter system (reviewed in references 7 and 15). In the case of the nisin family of lantibiotics, immunity is based on the action of both a LanFEG system and LanI protein. Despite the cross-protection referred to above, cross-immunity between lantibiotic producers is rare, with only a few exceptional examples (3, 22). Indeed, cross-immunity between producers of the closely related nisin A and subtilin peptides (63% identity) is not evident. Another unusual phenomenon is immune mimicry, whereby non-lantibiotic-producing strains express functional homologues of lantibiotic immunity systems. In the only study of this phenomenon to date, homologues of immunity genes associated with the lantibiotic lacticin 3147 were identified in Bacillus licheniformis DSM13 and Enterococcus faecium DO. It was shown that heterologous expression of these homologues provided protection against lacticin 3147 (14). The identification of this phenomenon is a concern and may represent a means by which populations of bacteria could emerge with resistance to specific lantibiotics. Notably, while a number of systems involved in acquired (19, 27) and innate resistance to nisin have been identified (8, 9), systems capable of providing resistance to any of the nisin peptides through immune mimicry have not been discovered heretofore.

Here we identify the first incidence of resistance by means of immune mimicry with respect to the nisin family. More specifically, genes encoding a homologue of the nisin U immunity-providing ABC transporter (NsuFEG) were identified within the genome of a non-lantibiotic-producing pathogen, Streptococcus infantarius subsp. infantarius BAA-102. Although the BAA-102 strain was recalcitrant to genetic manipulation, and thus the creation of a knockout mutant was not possible, heterologous expression confirms that SpiFEG and NsuFEG can protect against the action of nisin U and other members of the nisin family.

In silico screening for homologues of nisin immunity determinants.

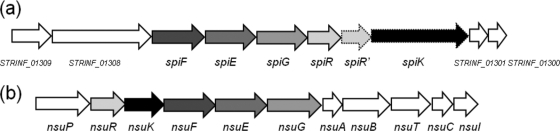

Immune mimicry is a recently identified phenomenon, and thus far, the only examples relate to the protection afforded against lacticin 3147 by homologues of its immunity proteins (14). To identify other examples of immune mimicry, a PSI-BLAST search (2) was undertaken using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) to determine if genes encoding homologues of the nisin immunity proteins could be identified in strains incapable of nisin production. This screening revealed the presence of the genes predicted to encode the components of an ABC transporter similar to that involved in nisin U immunity (NsuFEG [42]) within the genome of S. infantarius subsp. infantarius BAA-102 (38). The predicted product of STRINF_01307 (here referred to as spiF) resembled NsuF (67% identity, e value of 2e-83), while STRINF_01306 (here annotated as spiE) and STRINF_01305 (here referred to as spiG) are predicted to encode proteins that resemble NsuE (50% identity, e value of 4e-63) and NsuG (51% identity, e value of 5e-45), respectively. While the similarity between SpiFE and NsuFE is only marginally greater than that to NisFE, SpiG is only 35% identical to NisG. As a result of this discovery, other genes within this region of the BAA-102 genome were subjected to an in silico investigation to determine if other lantibiotic-associated genes might be present. Notably, the 3 genes immediately downstream from spiFEG all resembled those encoding the individual components of the nisin two-component system known as NisRK (or NsuRK in the case of nisin U [42]), which are responsible for regulating nisin biosynthesis and immunity (28) (Fig. 1). More specifically, the gene product of STRINF_01304 is 70% identical to the response regulator NsuR, with an e value of 1e-50 (and here referred to as spiR), and the adjacent gene (STRINF_01303; spiR′) also encodes an NsuR-like protein. Although SpiR and SpiR′ are 67% identical to NisR, the two proteins are predicted to be quite different from each other, being only 11% identical. Furthermore, the predicted product of STRINF_01302 is 50% identical (e value of 4e-112) to the histidine kinase NisK and 43% identical to NsuK (e value of 7e-101) (Fig. 1). Although none of the nisin-like compounds have multiple LanR proteins associated with their regulation, multiple LanR proteins can be found in the lantibiotic operons of RumA, mersacidin, and cytolysin (11, 18, 20). The NisR binding motif, a defined sequence of nucleotides by which NisR binds to the promoters of NisF and NisA, is referred to as a nis box (26). A sequence with high similarity to a nis box is found in the region upstream of spiFEG and theoretically could act as a binding motif for SpiR and/or SpiR′. It was noted that the percent GC content of spiFEGRR′K (33.5%) is lower than that observed in the entire BAA-102 genome (37.7%), and thus, the possibility that these genes were acquired through horizontal transfer cannot be discounted. Analysis of up- and downstream genes reveals that none of these possess lantibiotic-associated features. Indeed, further analysis of the BAA-102 genome failed to identify any other lantibiotic-associated genes. Interestingly with respect to SpiF, a conserved domain, the BcrA subfamily (cd03268), was identified; homology between this bacitracin-associated transporter and SpiG was also revealed.

Fig 1.

Genetic orientation of homologues of the nisin U (a) and nisin-associated immunity and regulatory (b) genes found in S. infantarius subsp. infantarius. The up- and downstream genes are included, and from BlastP analysis, their theoretical functions are as follows: STRINF_01300, UDP-N-acetyl-d-glucosamine 2-epimerase; STRINF_01301, hypothetical protein; STRINF_01308, hypothetical ATP-binding protein; STRINF_01309, hypothetical membrane protein.

The presence of the spiFEGRR′K genes in S. infantarius subsp. infantarius BAA-102 is noteworthy for a number of reasons. S. infantarius, referred to as S. bovis biotype II/1 before reclassification (5), has been isolated from the feces of infants, from clinical specimens associated with endocarditis, and from foods, including dairy products and frozen peas (1, 23, 38). This species can also contribute to the development of cancer, particularly in cases of chronic infection or inflammatory disease where the S. infantarius bacterial components interfere with cell function, leading to cell transformation and proliferation (4), and is most frequently associated with noncolonic digestive tract cancers (10). Notably, nisin U has been shown to be effective against a wide range of disease-associated streptococci, including Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus salivarius, S. uberis, Streptococcus agalactiae, and Streptococcus dysgalactiae, and thus, the possibility that a potential target such as S. infantarius may be resistant to nisin as a consequence of immune mimicry is worthy of note.

Heterologous expression of nsuFEG and spiFEG.

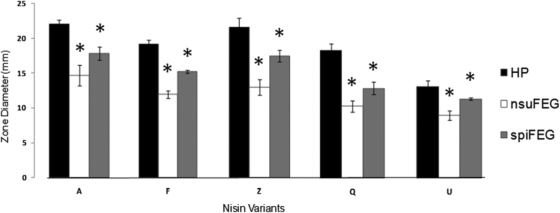

S. infantarius BAA-102 is, on the basis of deferred-antagonism assays (for the method, see reference 17), less sensitive to nisin U than are a number of other Streptococcus species tested (S. pyogenes, Streptococcus mitis, and S. agalactiae; data not shown). However, despite several attempts, we were unable to successfully transform BAA-102 as a prelude to creating isogenic spiFEG knockout mutants. As a consequence, we used heterologous expression as a strategy to determine whether the newly identified spiFEG genes could encode protection against nisin U. The corresponding nsuFEG genes from S. uberis 42 (24, 42) served as a positive control. To facilitate this, genomic DNA was extracted from S. uberis as described previously (14). The nsuFEG genes were amplified using primers AAAACTGCAGAAGTAGCAACTAGAAAG and GGGGTACCCTTTTAGGTGGCTAGTATCGC, and the primers for spiFEG were AAAACTGCAGAAAAGTTTGGGACTTCAATG and GGGGTACCCCTGTCACCTCAATTGTATTTG, where restriction enzyme sites are underlined. The resulting gene products and the shuttle expression vector pNZ44 (32) were digested with the relevant restriction enzymes, ligated, and introduced into electrocompetent L. lactis HP (via the intermediate host Escherichia coli TOP10) as described previously (14). Following confirmation of the integrity of the newly created vectors, deferred-antagonism assays were performed to provide an initial insight into the protection provided against the producer of nisin U and other nisins (A, Z, F, and Q [35]). These were carried out as described previously, using GM17 and TS agars for Lactococcus and Streptococcus, respectively (17). Relative sensitivity was assessed on the basis of zone size (Table 1). No inhibition was apparent when the nisin U producer was overlaid with L. lactis HP/pNZ44nsuFEG, thus establishing that the nisin U immunity proteins could provide protection when expressed heterologously to the otherwise nisin-sensitive HP strain. Notably, the presence of pNZ44spiFEG also provided protection against nisin U, with zone sizes decreasing substantially. The SpiFEG system is thus capable of providing protection through immune mimicry. The abilities of pNZ44nsuFEG and pNZ44spiFEG to protect HP against the actions of nisin A (produced by L. lactis NZ9700 [29]), nisin F (produced by L. lactis NZ9700/pCI372nisF [35]), nisin Z (produced by L. lactis NZ9700/pCI372nisZ [35]), nisin Q (produced by L. lactis NZ9700/pCI372nisQ [35]), and nisin U3 (41) were also assessed. It was established that heterologous expression of nsuFEG in strain HP provides protection against nisin U3 and to a lesser degree against nisin A, nisin F, nisin Z, and nisin Q, with zone sizes smaller than those observed when HP was used as the target (Table 1). The presence of pNZ44spiFEG also substantially reduced the sensitivity of the HP strain to nisin Z and nisin U3 (Table 1). To further assess the level of protection, the same collection of strains was employed to carry out a series of agarose-based well diffusion assays (Fig. 2) (13, 30). In this instance, the antimicrobials were present in the form of cell-free supernatant from overnight cultures of the nisin producers. The benefit of this approach is that the enhanced rate of diffusion of the antimicrobials through agarose (relative to agar) and the use of target cells in early-log-phase cells provide greater sensitivity. The results from these assays confirm the significantly enhanced resistance of HP/pNZ44nsuFEG to all forms of nisin and of HP/pNZ44spiFEG to nisins Z and U. However, in this instance, HP/pNZ44spiFEG also displayed significantly enhanced resistance to nisins A, F, and Q (Fig. 2). These investigations are consistent with those of Wirawan et al., who previously noted cross-protection between nisin-producing strains (42). Given that SpiFEG also resemble transporters involved in bacitracin resistance, the relative resistance of L. lactis HP and HP/pNZ44spiFEG to this antibiotic was tested via antibiotic disc assays (10 IU; Oxoid) (9). These assays revealed that spiFEG do not provide the HP strains with enhanced resistance to bacitracin (data not shown).

Table 1.

Deferred-antagonism assay analysis of the protective capabilities conferred by NsuFEG and SpiFEG when expressed in L. lactis HP, or the resistance of the natural S. infantarius isolate, against the action of a range of natural nisin variant producersa

| Nisin variant | Avg zone size (mm) ± SD |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP (control) | HP pNZ44nsuFEG | HP pNZ44spiFEG | S. infantarius | |

| A | 18.6 ± 0.71 | 16.3 ± 0.71 | 17.85 ± 1.06 | 2.94 ± 0.18 |

| F | 20.6 ± 1.00 | 17.79 ± 0.27 | 19.67 ± 1.00 | 5.84 ± 0.50 |

| Z | 24.4 ± 0.36 | 20.2 ± 0.14 | 21.85 ± 1.62 | 4.9 ± 0.74 |

| Q | 16.08 ± 0.65 | 14.8 ± 0.28 | 15.05 ± 1.62 | 4.17 ± 0.75 |

| U | 8.4 ± 0.42 | 0 | 4.7 ± 1.27 | 0b |

| U3 | 16.06 ± 0.18 | 0 | 12.2 ± 2.97 | 0b |

Values are averages of triplicate experiments and represent zone sizes, i.e., diameter of zone minus diameter of bacterial growth.

No distinct zone but some hazy growth adjacent to nisin-producing colony.

Fig 2.

Agarose well diffusion assay, whereby L. lactis HP/pNZ44 and strains expressing nsuFEG and spiFEG were challenged under adverse growth conditions with nisins A, F, Z, Q, and U. Asterisks indicate zone diameters which were significantly smaller by Student's t test (P < 0.0005) than that found in L. lactis HP, hence implying the protective capabilities of these genes.

Antimicrobial activity assays with purified nisin U.

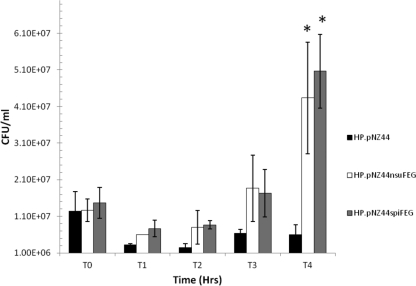

To better assess the extent to which SpiFEG provide protection from nisin U, broth-based assays with purified nisin U were carried out. To facilitate this, the lantibiotic was purified using an approach previously employed to purify nisin A and derivatives (17) but with some slight modifications. Specifically, the tryptone-yeast extract-glucose growth medium was supplemented with higher levels of glucose (11 g liter−1) and β-glycerophosphate (21 g liter−1) before the nisin U present in cell-free culture supernatant was isolated by passage through 60 g XAD-16 beads (prewashed with water), washed with 30% ethanol, and finally eluted with 70% isopropanol. This was combined with the nisin-containing 70% isopropanol from the purification of cell-attached nisin as previously described (17). Subsequent purification was performed using a 10-g (60-ml) Strata C18-E column (Phenomenex, Cheshire, United Kingdom) preequilibrated with methanol and water. The columns were washed with 30% ethanol, and the inhibitory activity was eluted in 70% isopropanol–0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Aliquots (20 ml) were concentrated to 2 ml through the removal of propan-2-ol by rotary evaporation before being applied to a Phenomenex C12 reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) column (Jupiter 4 μm Proteo 90 Å; 250 by 10.0 mm, 4 μm) previously equilibrated with 25% acetonitrile–0.1% TFA. The column was subsequently developed in a gradient of 30% acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA to 60% acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA from 10 to 45 min at a flow rate of 2.0 ml min−1. Fractions containing nisin U were collected after HPLC, acetonitrile was removed by rotary evaporation, and the protein was lyophilized by freeze-drying. Mass spectrometry was performed with an Axima CFR plus matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometer as previously described (17), which confirmed that the final purified product was nisin U. The purified nisin U was employed in studies to compare the growth of HP, HP/pNZ44nsuFEG, and HP/pNZ44spiFEG in the presence of 416 nM nisin U over 4 h in broth (Fig. 3). This was assessed by inoculating 1 × 107 CFU/ml of target cells into fresh broth containing nisin U, incubating them at 30°C, and at intervals removing aliquots, which were subjected to serial dilution in 1/4-strength Ringer's solution and plated on GM17 agar. All growth experiments were performed in triplicate with samples from three separate overnight cultures and repeated on at least three different days. These assays revealed that after 4 h, the numbers of HP bacteria expressing nsuFEG and spiFEG were significantly (P < 0.014) greater than those of the corresponding HP control (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Survival and growth of L. lactis strain HP and strains expressing NsuFEG and SpiFEG when challenged with a sublethal level (416 nM) of nisin U. An asterisk at T4 indicates that the difference between strain HP/pNZ44 and the strains expressing immunity genes is statistically significant (Student's t test P < 0.014).

Assessing the relative protection provided through heterologous expression of spiFEGRR′K.

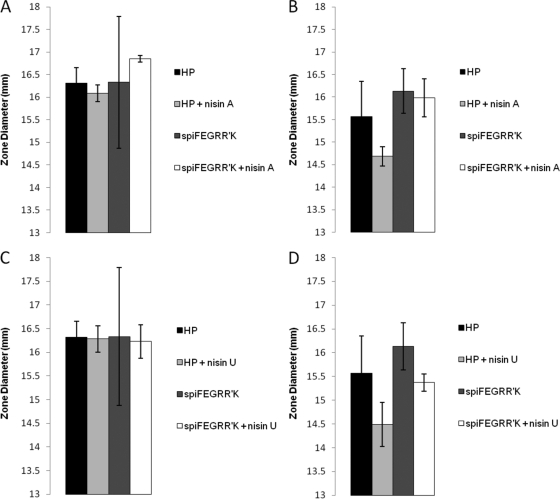

We postulated that the products of spiRR′K may sense and respond to the presence of nisin to further enhance the expression of spiFEG and nisin resistance. However, should such a phenomenon exist, it would be mediated through the nis box within the promoter upstream of spiFEG (Pspi). To investigate this possibility, heterologous expression was again employed. Pspi-spiFEGRR′K was amplified using primers GGGGTACCGAAGGTTGGACAGAAGTTTGG and GCTGCAGACCATGTCGTAAATAGTCGTTTTTTC and digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes (Fastdigest; Fermentas) (21). This was ligated with similarly digested pCI372 (a shuttle vector which, unlike pNZ44, does not contain a constitutive promoter to drive the expression of cloned genes) and transformed into electrocompetent L. lactis HP. A phenotypic assay was performed to assess if exposure to sublethal concentrations of nisin A or nisin U enhanced the ability of pCI372Pspi-spiFEGRR′K to provide protection from a subsequent challenge with concentrated nisin. Specifically, overnight cultures of L. lactis HP/pCI372 and HP/pCI372Pspi-spiFEGRR′K were inoculated (3%) into fresh GM17 and incubated until they reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.3, whereupon 1 ml of cells was exposed to a sublethal concentration (0.3 μM) of nisin A or nisin U for 1 h in 1.5-ml tubes at 30°C. The cells were then washed in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer and seeded in 1/100-strength GM17-agarose into which wells had been bored. Approximately 30 μM nisin A and nisin U were incubated in the wells for 3 h and subsequently overlaid with 2× GM17-agarose to allow growth of L. lactis strains (see references 13 and 30 for the method used). Having determined relative sensitivity on the basis of zone size, we found that in no instance did exposure to a sublethal concentration of nisin significantly enhance the protection provided by pCI372Pspi-spiFEGRR′K to subsequent exposure to higher concentrations of nisin (Fig. 4). It should be noted, however, that this does not preclude the possibility that SpiRR′K sense and respond to the presence of nisin in their native background.

Fig 4.

L. lactis HP expressing the genes spiFEGRR′K under the control of their native promoter in the vector pCI372 was assessed to discover if immunity could be induced in the presence of nisin. L. lactis HP was incubated in the presence of approximately 10 ng of either nisin A (A, B) or nisin U (C, D) prior to being challenged by agarose well diffusion assay with both nisin A (A, C) and nisin U (B, D). L. lactis HP/pCI372 alone was included as a control. The data show that the action of the spiFEG genes has not been induced and thus they are not active under these conditions.

As a consequence of the continued emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, the possibility of using ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial peptides such as the lantibiotics as alternative chemotherapeutic agents has received attention (34). Despite nisin having been used for over half a century for food applications, the development of resistance has not become a problem. Nonetheless, it has been established that some bacteria possess innate nisin resistance mechanisms and that others can become resistant upon exposure to nisin in the laboratory (8, 9, 27). It is thus a concern that the use of nisin and other lantibiotics for clinical applications could also result in the emergence of resistant strains. However, it is hoped that by developing a clearer understanding of the various different mechanisms by which resistance can emerge, it will be possible to develop strategies to counteract such occurrences. The phenomenon of resistance through immune mimicry has been described on only one previous occasion (14), and thus, the identification of nisin immunity determinants in the genome of BAA-102 is noteworthy. On the basis of these findings, this phenomenon may be more common than has previously been appreciated, and the possibility that the presence and transfer of such genes could potentially lead to the emergence of lantibiotic-resistant strains needs to be considered carefully.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Irish Government under the National Development Plan through Science Foundation Ireland Investigator awards 06/IN.1/B98 and 10/IN.1/B3027.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 7 November 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Abdelgadir W, Nielsen DS, Hamad S, Jakobsen M. 2008. A traditional Sudanese fermented camel's milk product, Gariss, as a habitat of Streptococcus infantarius subsp. infantarius. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 127:215–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Altschul SF, et al. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aso Y, et al. 2005. A novel type of immunity protein, NukH, for the lantibiotic nukacin ISK-1 produced by Staphylococcus warneri ISK-1. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 69:1403–1410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Biarc J, et al. 2004. Carcinogenic properties of proteins with pro-inflammatory activity from Streptococcus infantarius (formerly S. bovis). Carcinogenesis 25:1477–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bouvet A, et al. 1997. Streptococcus infantarius sp. nov. related to Streptococcus bovis and Streptococcus equinus. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 418:393–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cao LT, Wu JQ, Xie F, Hu SH, Mo Y. 2007. Efficacy of nisin in treatment of clinical mastitis in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 90:3980–3985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chatterjee C, Paul M, Xie L, van der Donk WA. 2005. Biosynthesis and mode of action of lantibiotics. Chem. Rev. 105:633–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Collins B, Curtis N, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. 2010. The ABC transporter AnrAB contributes to the innate resistance of Listeria monocytogenes to nisin, bacitracin, and various beta-lactam antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4416–4423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Collins B, Joyce S, Hill C, Cotter PD, Ross RP. 2010. TelA contributes to the innate resistance of Listeria monocytogenes to nisin and other cell wall-acting antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4658–4663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Corredoira J, Alonso MP, Coira A, Varela J. 2008. Association between Streptococcus infantarius (formerly S. bovis II/1) bacteremia and noncolonic cancer. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cox CR, Coburn PS, Gilmore MS. 2005. Enterococcal cytolysin: a novel two component peptide system that serves as a bacterial defense against eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 6:77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Kwaadsteniet M, Ten Doeschate K, Dicks LM. 2008. Characterization of the structural gene encoding nisin F, a new lantibiotic produced by a Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis isolate from freshwater catfish (Clarias gariepinus). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:547–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Derache C, et al. 2009. Primary structure and antibacterial activity of chicken bone marrow-derived beta-defensins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4647–4655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Draper LA, et al. 2009. Cross-immunity and immune mimicry as mechanisms of resistance to the lantibiotic lacticin 3147. Mol. Microbiol. 71:1043–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Draper LA, Ross RP, Hill C, Cotter PD. 2008. Lantibiotic immunity. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 9:39–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fernández L, Delgado S, Herrero H, Maldonado A, Rodriguez JM. 2008. The bacteriocin nisin, an effective agent for the treatment of staphylococcal mastitis during lactation. J. Hum. Lact. 24:311–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Field D, Connor PM, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. 2008. The generation of nisin variants with enhanced activity against specific gram-positive pathogens. Mol. Microbiol. 69:218–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gomez A, Ladire M, Marcille F, Fons M. 2002. Trypsin mediates growth phase-dependent transcriptional regulation of genes involved in biosynthesis of ruminococcin A, a lantibiotic produced by a Ruminococcus gnavus strain from a human intestinal microbiota. J. Bacteriol. 184:18–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gravesen A, Sorensen K, Aarestrup FM, Knochel S. 2001. Spontaneous nisin-resistant Listeria monocytogenes mutants with increased expression of a putative penicillin-binding protein and their sensitivity to various antibiotics. Microb. Drug Resist. 7:127–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guder A, Schmitter T, Wiedemann I, Sahl HG, Bierbaum G. 2002. Role of the single regulator MrsR1 and the two-component system MrsR2/K2 in the regulation of mersacidin production and immunity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:106–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hayes F, Daly C, Fitzgerald GF. 1990. Identification of the minimal replicon of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis UC317 plasmid pCI305. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:202–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heidrich C, et al. 1998. Isolation, characterization, and heterologous expression of the novel lantibiotic epicidin 280 and analysis of its biosynthetic gene cluster. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3140–3146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoshino T, Fujiwara T, Kilian M. 2005. Use of phylogenetic and phenotypic analyses to identify nonhemolytic streptococci isolated from bacteremic patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:6073–6085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jayarao BM, Oliver SP, Tagg JR, Matthews KR. 1991. Genotypic and phenotypic analysis of Streptococcus uberis isolated from bovine mammary secretions. Epidemiol. Infect. 107:543–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaletta C, Entian KD. 1989. Nisin, a peptide antibiotic: cloning and sequencing of the nisA gene and posttranslational processing of its peptide product. J. Bacteriol. 171:1597–1601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kleerebezem M. 2004. Quorum sensing control of lantibiotic production; nisin and subtilin autoregulate their own biosynthesis. Peptides 25:1405–1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kramer NE, van Hijum SA, Knol J, Kok J, Kuipers OP. 2006. Transcriptome analysis reveals mechanisms by which Lactococcus lactis acquires nisin resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1753–1761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kuipers OP, Beerthuyzen MM, de Ruyter PG, Luesink EJ, de Vos WM. 1995. Autoregulation of nisin biosynthesis in Lactococcus lactis by signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 270:27299–27304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kuipers OP, Beerthuyzen MM, Siezen RJ, De Vos WM. 1993. Characterization of the nisin gene cluster nisABTCIPR of Lactococcus lactis. Requirement of expression of the nisA and nisI genes for development of immunity. Eur. J. Biochem. 216:281–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lehrer RI, Rosenman M, Harwig SS, Jackson R, Eisenhauer P. 1991. Ultrasensitive assays for endogenous antimicrobial polypeptides. J. Immunol. Methods 137:167–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lubelski J, Rink R, Khusainov R, Moll GN, Kuipers OP. 2008. Biosynthesis, immunity, regulation, mode of action and engineering of the model lantibiotic nisin. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65:455–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McGrath S, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. 2001. Improvement and optimization of two engineered phage resistance mechanisms in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:608–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mulders JW, Boerrigter IJ, Rollema HS, Siezen RJ, de Vos WM. 1991. Identification and characterization of the lantibiotic nisin Z, a natural nisin variant. Eur. J. Biochem. 201:581–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Piper C, Cotter PD, Ross RP, Hill C. 2009. Discovery of medically significant lantibiotics. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 6:1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Piper C, Hill C, Cotter PD, Ross RP. 2011. Bioengineering of a nisin A-producing Lactococcus lactis to create isogenic strains producing the natural variants nisin F, Q, and Z. Microb. Biotechnol. 4:375–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rogers LA. 1928. The inhibiting effect of Streptococcus lactis on Lactobacillus bulgaricus. J. Bacteriol. 16:321–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rogers LA, Whittier EO. 1928. Limiting factors in the lactic fermentation. J. Bacteriol. 16:211–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schlegel L, et al. 2000. Streptococcus infantarius sp. nov., Streptococcus infantarius subsp. infantarius subsp. nov. and Streptococcus infantarius subsp. coli subsp. nov., isolated from humans and food. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50(Pt. 4):1425–1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sears PM, et al. 1992. Evaluation of a nisin-based germicidal formulation on teat skin of live cows. J. Dairy Sci. 75:3185–3190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Severina E, Severin A, Tomasz A. 1998. Antibacterial efficacy of nisin against multidrug-resistant Gram-positive pathogens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 41:341–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wirawan RE. 2007. An investigation into the antimicrobial repertoire of Streptococcus uberis. Ph.D. thesis University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wirawan RE, Klesse NA, Jack RW, Tagg JR. 2006. Molecular and genetic characterization of a novel nisin variant produced by Streptococcus uberis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1148–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wu J, Hu S, Cao L. 2007. Therapeutic effect of nisin Z on subclinical mastitis in lactating cows. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3131–3135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zendo T, et al. 2003. Identification of the lantibiotic nisin Q., a new natural nisin variant produced by Lactococcus lactis 61-14 isolated from a river in Japan. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 67:1616–1619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]