Abstract

Exposure-response analyses for efficacy and safety were performed for tigecycline-treated patients suffering from community-acquired pneumonia. Data were collected from two randomized, controlled clinical trials in which patients were administered a 100-mg loading dose followed by 50 mg of tigecycline every 12 h. A categorical endpoint, success or failure, 7 to 23 days after the end of therapy (test of cure) and a continuous endpoint, time to fever resolution, were evaluated for exposure-response analyses for efficacy. Nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, headache, and changes in blood urea nitrogen concentration (BUN) and total bilirubin were evaluated for exposure-response analyses for safety. For efficacy, ratios of the free-drug area under the concentration-time curve at 24 h to the MIC of the pathogen (fAUC0-24:MIC) of ≥12.8 were associated with a faster time to fever resolution; patients with lower drug exposures had a slower time to fever resolution (P = 0.05). For safety, a multivariable logistic regression model demonstrated that a tigecycline AUC above a threshold of 6.87 mg · hr/liter (P = 0.004) and female sex were predictive of the occurrence of nausea and/or vomiting (P = 0.004). Although statistically significant, the linear relationship between tigecycline exposure and maximum change from baseline in total bilirubin is unlikely to be clinically significant.

INTRODUCTION

Tigecycline represents the first of a new generation of antibiotics derived from tetracyclines, the glycylcyclines. During the course of its development, tigecycline has been the subject of several pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) analyses, using data from animal infection models as well as data from clinical trials of patients suffering from complicated skin and skin structure infections or those with complicated intra-abdominal infections (3, 4, 8). These analyses have characterized the magnitude of the ratio of the area under the concentration-time curve at 24 h to the MIC of the pathogen (AUC0-24:MIC), the PK-PD measure most predictive of outcome, which is associated with efficacy.

In the analyses described here, pharmacokinetic (PK) and clinical data from two clinical trials of patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) were integrated to conduct PK-PD analyses of both efficacy and safety. Patient-specific PK parameter estimates were available from a population PK analysis of these data and were used to provide the most accurate estimates of exposure possible (6). These exposure estimates were indexed to the MIC of the infecting pathogen(s) and used to explore exposure-response relationships for efficacy. Exposure estimates also were used to explore exposure-response relationships for safety outcomes of interest.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population.

The population for these analyses consisted of tigecycline-treated patients from two different studies, 3074A1-308-WW (study 308) and 3074A1-313-WW (study 313) (7). In brief, both studies were phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind comparisons of the efficacy and safety of tigecycline to those of levofloxacin in patients initially hospitalized with CAP.

Ambulatory patients 18 years of age and older who had a clinical diagnosis of CAP requiring hospitalization and who had a lack of prior antibiotic treatment for CAP (not more than 1 dose of a non-once-daily, non-study antibacterial with the exception of a failed course of outpatient antibiotics) were eligible for enrollment. The clinical diagnosis of CAP required a chest X-ray showing the presence of a new infiltrate, fever (or hypothermia) within 24 h of enrollment, and clinical criteria consisting of at least two of the following: cough, purulent sputum, auscultatory findings of rales and/or evidence of pulmonary consolidation, dyspnea or tachypnea, elevated white blood cell count or leukopenia, and hypoxemia.

Patients were excluded for any of the following reasons: hospitalization within 14 days prior to the onset of symptoms; residence in a long-term care facility for 14 days before the onset of symptoms; treatment in the intensive care unit required; receipt of an organ or bone marrow transplant or chronic immunosuppressive therapy; presence of excluded concomitant diseases, including human immunodeficiency virus, cystic fibrosis, active tuberculosis, primary lung cancer, and any malignancy metastatic to the lungs; known or suspected hypersensitivity to either treatment; neutropenia; increased aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase (>10× upper limit of normal) or bilirubin (>3× upper limit of normal); calculated creatinine clearance (CLCR) of <20 ml/min; known or suspected concomitant bacterial infection requiring treatment with additional antibacterial agent(s); outpatient ventilator therapy within 14 days before the onset of symptoms; or treatment with drugs known to prolong the QT interval.

Drug dosage and administration.

For both studies, those patients randomized to tigecycline received an intravenous (i.v.) loading dose of 100 mg of tigecycline followed by 50 mg i.v. of tigecycline every 12 h. Treatment between the studies differed in the following manner: (i) patients were required to have at least 3 days of i.v. therapy in study 308 and a minimum of 7 days of i.v. therapy in study 313, and (ii) a 30-min infusion was used for study 308 and a 60-min infusion in study 313.

Efficacy outcome evaluation.

The clinical response for CAP was determined by comparing the patient's baseline signs and symptoms of infection to those after therapy. Success was defined as the resolution or improvement of all signs and symptoms present at study entry at the test-of-cure visit (approximately 7 to 23 days after the end of therapy) without the need for further antibiotics. Failure was defined as any one or more of the following circumstances: persistent or worsened signs and symptoms after at least 2 days of therapy, new clinical findings consistent with the progression of infection, progressive radiological abnormalities, additional antibiotic therapy needed, and/or death due to CAP.

Microbiologically evaluable patients were those clinically evaluable patients with one or more susceptible pretreatment pathogens. All antimicrobial susceptibility testing was conducted at Wyeth Research using standard media and procedures. The microbiological response to therapy at the patient level was classified as either eradicated (which included eradicated or presumed eradicated), persistent (which included persistent or presumed persistent), superinfection, or indeterminate. Eradicated was defined as the absence of the pretreatment pathogen(s) from the posttreatment culture. If the clinical response was classified as a success and no material was available for culture, the pretreatment pathogen(s) was presumed to be eradicated. Persistence was defined as the presence of the pretreatment pathogen(s) in the posttreatment culture. If the clinical response was classified as a failure and no material was available for culture, the pretreatment pathogen(s) was presumed to be persistent.

Given the availability of serial body temperature assessments, time to defervescence also was evaluated as an efficacy outcome. The most abnormal temperature reading for the day was recorded in the case report form. Defervescence was defined as being afebrile for more than 48 h, and the time to defervescence was defined as the time to the midpoint of the interval between the last febrile temperature measure and the first afebrile temperature measure.

Safety outcome evaluation.

Two types of safety outcomes were evaluated, dichotomous indications of the occurrence of drug-related adverse events and continuous laboratory measures. Due to their common occurrence in the population of tigecycline-treated patients (9), the dichotomous events (yes and no) evaluated for this analysis were the occurrence of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or headache if deemed by the investigator to be definitely, probably, or possibly related to the study drug. The continuous measures evaluated for this analysis were maximum changes from baseline in blood urea nitrogen concentration (BUN) and total bilirubin. BUN was selected due to the relatively high occurrence of elevated BUN in the overall population of tigecycline-treated patients, which is consistent with effects reported for minocycline (2), and total bilirubin was selected because tigecycline is eliminated primarily via biliary excretion.

Calculation of exposure and PK-PD index: AUC0-24 and the ratio of the free-drug AUC0-24 to the MIC (fAUC0-24:MIC).

The 24-h area under the concentration-time curve (AUC0-24) at steady state was calculated according to equation 1:

| (1) |

where dose is equal to the total daily dose of tigecycline (100 mg) and CLT is the Bayesian post hoc clearance value generated from a previously conducted population PK analysis (6). In brief, the final population PK model was a two-compartment model with linear elimination. The model was parameterized using total clearance (mean [% coefficient of variation {CV}], 19.2 [40.4] liters/h), volume of central compartment (mean [%CV], 65.2 [82.1] liters), distributional clearance from the central to the peripheral compartment (mean [% CV], 85.1 [110] liters/h), and volumes of distribution at steady state (mean [% CV], 398 [40.2] liters). Covariate analyses identified body surface area and creatinine clearance as significant predictors of the interindividual variability on CL. The model fit the tigecycline concentrations well, as evidenced by the plot of observed versus model-fitted concentrations (r2 = 0.992 for the line of best fit with a slope and intercept of 1.07 and −0.0157, respectively); the plot of individual weighted residuals versus predicted concentrations showed no apparent bias in the fit.

AUC0-24 represented the exposure measure of interest for the PK-PD analysis for safety. The PK-PD measure of interest for the efficacy analyses, fAUC0-24:MIC, was calculated using equation 2:

| (2) |

where fu is the fraction unbound for tigecycline (assumed to be 0.20 [9]) and MIC indicates the MIC value for baseline pathogen(s).

PK-PD analyses for efficacy.

Data for patients who were clinically and microbiologically evaluable, had PK parameter estimates, and had baseline MIC values from one or more pathogens were included in the exposure-response analyses for efficacy. For those patients with more than one baseline pathogen, the fAUC0-24:MIC ratio evaluated was based upon the pathogen with the highest MIC. Exposure-response analyses for efficacy undertaken involved the evaluation of three endpoints for efficacy, clinical response (success versus failure), microbiological response (eradication versus persistence), and time to defervescence. Three cohorts of evaluable patients were considered: (i) patients with monomicrobial Streptococcus pneumoniae infections, (ii) patients with either mono- or polymicrobial S. pneumoniae infections, and (iii) all patients, regardless of pathogen.

PK-PD analyses were performed using Systat software, version 11.0 (Richmond, CA). Exploratory analyses of clinical and microbiological responses were conducted to identify relationships between response and fAUC0-24:MIC. This included the examination of the relationship between fAUC0-24:MIC and percent response among patients grouped by quartiles or deciles. Threshold values for fAUC0-24:MIC distinguishing cohorts of patients with impressive differences in response also were evaluated using classification and regression tree analysis (CART), as implemented in Systat. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses, with backward elimination (α = 0.05), were used to determine whether the fAUC0-24:MIC ratio or other independent variables, as described in Table 1, were statistically significant predictors of clinical or microbiological responses.

Table 1.

Demographic and disease characteristics evaluated for effect on PK-PD endpoints

| Continuous variable (demographic) | Categorical variable |

|

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Diseasec | |

| Age (yr) | Ethnicity | Alcohol abuse |

| Height (cm) | Nursing home resident | Cerebrovascular disease |

| Weighta (kg) | Sex | CHF |

| COPD | ||

| Current smoker | ||

| Diabetes | ||

| FPSIb | ||

| Liver disease | ||

| MICa,b | ||

| Neoplastic disease | ||

| Previous smoker | ||

| Renal disease | ||

Baseline values were used for these variables.

Considered only for PK-PD analyses for efficacy.

CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FPSI, fine pneumonia severity index.

The analyses described above were conducted in a stepwise fashion. The most homogeneous cohort was evaluated initially (cohort 1; patients with monomicrobial S. pneumoniae infections). If the number of failures in cohort 1 was deemed inadequate to detect relationships of importance, the analyses described above were carried out for cohort 2 (patients with monomicrobial and polymicrobial S. pneumoniae infections pooled together). If there were insufficient failures in cohort 2, the analyses were conducted using the largest but least homogenous cohort, cohort 3, which contained all patients regardless of pathogen.

The data for time to defervescence were analyzed using time-to-event analyses. Univariable relationships between time to defervescence and fAUC0-24:MIC, evaluated as a continuous variable, were explored using a Cox proportional hazards model. Additionally, threshold values for fAUC0-24:MIC distinguishing cohorts of patients with impressive differences in time to defervescence were evaluated using CART. In cases where the threshold values were determined, the significance of a dichotomous variable based on such a threshold value then was tested, first using stratified Kaplan-Meier and then, if significant at a level of α = 0.1, as a covariate in a multivariable model as described below. Other potential predictors of time to defervescence, as described in Table 1, were evaluated univariably in a similar manner. All potential predictors deemed significant in a univariable fashion were evaluated using a multivariable Cox model and backward stepwise elimination (α = 0.05).

PK-PD analyses for safety.

Similarly to those conducted for efficacy, exploratory analyses of safety outcomes were conducted to identify relationships between outcome and exposure (in this case, the AUC0-24) among patients with PK parameter estimates. For the dichotomous adverse events (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and headache), this included the examination of the relationship between the AUC0-24 and the percent occurrence of the event among patients grouped by quartiles, deciles, or groups of equal size. Threshold values for AUC0-24 distinguishing cohorts of patients with impressive differences in the occurrence of adverse events were evaluated using CART. The relationship between adverse events and other independent variables, as described in Table 1, also was evaluated. For the continuous laboratory measures BUN and total bilirubin, separate scatterplots of AUC0-24 versus the maximum change in the laboratory value relative to the baseline were created to explore visual evidence for an exposure-response relationship.

When the exploratory analyses indicated that potential trends existed, univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses (or multiple linear regression for continuous variables), with backward elimination (α = 0.05), were carried out using Systat software, version 11.0, to determine whether the independent variables described above were statistically significant predictors of the occurrence of an adverse event or a change in a laboratory value.

RESULTS

Patient population.

In the two clinical studies, 165 patients randomized to receive tigecycline were clinically and microbiologically evaluable. Of these, a total of 68 patients had at least one pathogen isolated at baseline with a corresponding MIC value and had the requisite PK parameter values. Given that 11 patients had polymicrobial infections, 81 pathogens were isolated from 68 patients. S. pneumoniae was the most common pathogen; 34 and 8 patients had monomicrobial and polymicrobial S. pneumoniae infections, respectively.

As described earlier, patients were divided into three cohorts (monomicrobial S. pneumoniae, mono- and polymicrobial S. pneumoniae, and all patients). Summary statistics for the demographic variables, stratified by cohort, are provided in Table 2. The distribution of successes and failures for clinical and microbiological responses, stratified by cohort, is shown in Table 3. Of the five failures for clinical and microbiological responses, three were associated with streptococci.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics stratified by cohort

| Cohort (n) | Age (yr) |

Weight (kg) |

Height (cm) |

CLCR (ml/min/1.73 m2) |

Sex (n [%]) |

No. (%) with FPSIa value: |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (min-max) | Mean (SD) | Median (min-max) | Mean (SD) | Median (min-max) | Mean (SD) | Median (min-max) | Male | Female | I | II | III | IV | V | |

| 1b (34) | 48.4 (13.4) | 51.0 (20.0-76.0) | 74.7 (18.0) | 73.0 (46.5-123) | 171 (9.94) | 173 (147-193) | 79.5 (37.0) | 76.2 (22.1-228) | 23 (67.7) | 11 (32.3) | 3 (8.8) | 14 (41.2) | 7 (20.6) | 10 (29.4) | 0 (0) |

| 2c (42) | 49.8 (15.0) | 51.5 (18.0-83.0) | 74.2 (16.7) | 72.5 (46.5-123) | 171 (9.84) | 172 (147-193) | 78.4 (38.7) | 74.0 (22.1-228) | 29 (69.1) | 13 (30.9) | 4 (9.5) | 15 (35.7) | 11 (26.2) | 12 (28.6) | 0 (0) |

| 3d (68) | 50.9 (16.1) | 51.5 (18.0-83.0) | 76.4 (18.5) | 74 (46.5-140) | 169 (9.91) | 170 (147-193) | 81.1 (34.3) | 76.2 (22.1-228) | 42 (61.8) | 26 (38.2) | 12 (17.7) | 22 (32.4) | 15 (22.1) | 19 (27.9) | 0 (0) |

Fine pneumonia severity index.

Patients with monomicrobial S. pneumoniae infections.

Patients with either mono- or polymicrobial S. pneumoniae infections.

All patients evaluated, regardless of pathogen.

Table 3.

Distribution of efficacy outcomes, stratified by cohort

| Cohort (n) | No. (%) by clinical response |

No. (%) by microbiological responsea |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success | Failure | Eradicated | Persistent | |

| 1 (34) | 33 (97.1) | 1 (2.9) | 33 (97.1) | 1 (2.9) |

| 2 (42) | 39 (92.9) | 3 (7.1) | 39 (92.9) | 3 (7.1) |

| 3 (68) | 63 (92.7) | 5 (7.3) | 63 (92.7) | 5 (7.3) |

Eradicated includes confirmed and presumed eradicated, and persistent includes confirmed and presumed persistent.

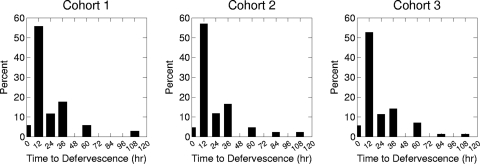

Since clinical and microbiological responses were 100% concordant, microbiological response only was examined in the PK-PD analyses. Moreover, due to the low incidence of microbiological failures, no statistical analyses were conducted for cohorts 1 and 2. The distributions of time to defervescence for each cohort are shown in Fig. 1. To balance the need for adequate data with the desire to have a relatively homogenous group of patients with respect to the infecting pathogen, cohort 2 was chosen for the examination of the relationship between time to defervescence and fAUC0-24:MIC.

Fig 1.

Distribution of time to defervescence by cohort. Two patients do not appear in the distribution for cohort 3 because they never became afebrile.

Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analyses for microbiological response.

Table 4 shows summary statistics for fAUC0-24:MIC stratified by cohort. Univariable analysis of data from patients in cohort 3 revealed that the fAUC0-24:MIC ratio was not a significant predictor of response. As shown in Table 5, sex was the only variable with a significant univariable relationship with microbiological response. With regard to the MIC distribution, which ranged from 0.03 to 1 mg/liter, Haemophilus (n = 2), Klebsiella (n = 2), and Neisseria species (n = 2) demonstrated MIC values of 0.5 or 1 mg/liter.

Table 4.

Summary statistics for fAUC0-24:MIC, stratified by cohort

| Cohort (n) | Mean (SD) | Median (min-max) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (34) | 16.3 (6.41) | 14.3 (9.22-35.9) |

| 2 (42) | 14.7 (6.91) | 13.1 (1.64-35.9) |

| 3 (68) | 12.2 (8.11) | 11.1 (1.04-35.9) |

Table 5.

Results of univariable analysis of microbiological response for cohort 3

| Covariate | No. (%) by microbiological response |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Persistent | Eradicated | ||

| Sex | 0.0459 | ||

| Male | 1 (2.4) | 41 (97.6) | |

| Female | 4 (15.4) | 22 (84.6) | |

| FPSI value | 0.289 | ||

| I | 1 (8.3) | 11 (91.7) | |

| II | 0 (0) | 22 (100) | |

| III | 1 (6.7) | 14 (93.3) | |

| IV | 3 (15.8) | 16 (84.2) | |

| MIC | 0.190 | ||

| 0.03 | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | |

| 0.06 | 0 (0) | 33 (100) | |

| 0.12 | 2 (20.0) | 8 (80.0) | |

| 0.25 | 2 (15.4) | 11 (84.6) | |

| 0.5 | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | |

| 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | |

When these variables were included in a multivariable logistic regression model using backward stepping, none were significant at a P value of 0.05. In an attempt to increase the sensitivity of the analysis, both the MIC and fine pneumonia severity index (FPSI) were evaluated as dichotomous variables (MIC at a value of 0.12 mg/liter and FPSI at a value of III). The evaluation of these variables in this manner also failed to demonstrate a significant relationship with microbiological response.

Time to defervescence.

There were a total of 40 patients from cohort 2 that were evaluable for this analysis; two patients with a time to defervescence of zero were excluded, since they were not febrile at baseline. Fever resolved in all of the remaining patients from cohort 2, and thus, there was no censoring of observations.

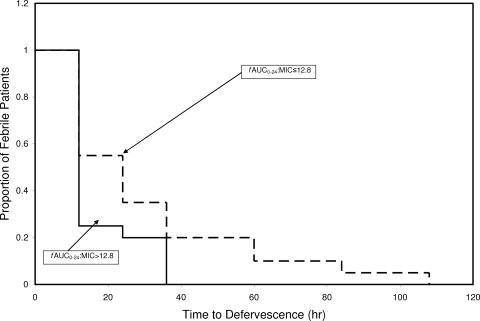

When assessed as a continuous variable in a Cox proportional hazards model, fAUC0-24:MIC failed to show a significant relationship with time to defervescence. Using CART, a threshold fAUC0-24:MIC value of 12.8 was found to be predictive of time to defervescence; the median (25th percentile and 75th percentile) time to defervescence in hours for patients above and at or below the threshold was 12 (12, 18) (n = 20) and 24 (12, 36) (n = 20), respectively. When fAUC0-24:MIC, dichotomized based on this threshold (12.8), was evaluated as a stratification variable in a Kaplan-Meier time-to-event analysis, patients with fAUC0-24:MIC values greater than or less than or equal to this threshold showed significant differences in time to defervescence (P = 0.05) (Fig. 2). As censoring is not required for this cohort, a simple nonparametric comparison of the time to defervescence between the two groups can be made. This comparison demonstrated borderline significance (P = 0.051 by Kruskall-Wallis).

Fig 2.

Stratified Kaplan-Meier curves for time to defervescence stratified by fAUC0-24:MIC threshold.

Exploratory plots failed to reveal any other independent variables with a potential effect on time to defervescence. However, given the univariable relationships observed for microbiological response and sex, FPSI, and MIC, these independent variables, along with age, were explored further. None of these variables were significant using univariable, stratified Kaplan-Meier time-to-event analysis.

Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analyses for safety.

Adverse events, laboratory data, and PK parameter estimates were available for all of the 289 patients treated with tigecycline. Summary statistics for demographic characteristics are provided in Table 6. The mean (standard deviations [SD]) and median (minimum to maximum) values for AUC0-24 were 5.41 (2.50) and 4.75 (1.82 to 17.3), respectively. The frequency distribution histogram for AUC0-24 is provided in Fig. 3.

Table 6.

Demographic characteristics of the safety analysis cohort (n = 289)

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Median (min-max) | No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 54.4 (17.3) | 56.0 (18.0-92.0) | |

| Weight (kg) | 74.4 (18.7) | 73.0 (33.8-140) | |

| Height (cm) | 167 (10.9) | 168 (136-198) | |

| CLCR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 83.6 (47.6) | 75.8 (20.2-507) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 160 (55.4) | ||

| Female | 129 (44.6) | ||

| FPSI value | |||

| I | 50 (17.3) | ||

| II | 94 (32.5) | ||

| III | 83 (28.7) | ||

| IV | 60 (20.8) | ||

| V | 2 (0.7) |

Fig 3.

Frequency distribution for AUC0-24 in the safety analysis cohort.

The incidence of the selected dichotomous adverse events examined among the 289 patients in the safety analysis cohort is provided in Table 7. Given the relationship between nausea and vomiting, these adverse events were combined such that patients who had either nausea or vomiting or both were examined (designated as nausea/vomiting).

Table 7.

Incidence of selected dichotomous adverse events in the safety analysis cohort

| Adverse event | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Diarrhea | |

| Absent | 270 (93.4) |

| Present | 19 (6.6) |

| Headache | |

| Absent | 279 (96.5) |

| Present | 10 (3.5) |

| Nausea | |

| Absent | 231 (80) |

| Present | 58 (20) |

| Vomiting | |

| Absent | 260 (90) |

| Present | 29 (10) |

| Nausea/vomiting | |

| Absent | 226 (78.2) |

| Present | 63 (21.8) |

When the proportion of individual dichotomous adverse events were evaluated relative to the AUC0-24 values grouped by deciles (data not shown), no trend for increasing incidence of either diarrhea or headache with increasing AUC0-24 was evident. However, there was a clear trend for a higher incidence of nausea/vomiting with increasing AUC0-24. Using CART, a threshold AUC0-24 of 6.87 mg · h/liter was found to be predictive of nausea/vomiting. Patients with AUC0-24 values at and above and below the threshold value had an incidence of nausea/vomiting of 40.4 and 17.2%, respectively (P = 0.00015 by chi-square test).

Based on univariable logistic regression, AUC0-24, evaluated as a continuous variable, was a significant predictor of nausea/vomiting (P = 0.00371; odds ratio, 1.17 [95% confidence intervals {CI}, 1.05, 1.29]; McFadden's ρ2 = 0.0278). Every 1-mg · h/liter increase in AUC0-24 was associated with a 17% increase in the likelihood of nausea/vomiting. The examination of the above-described CART-derived threshold of AUC0-24 of 6.87 mg · h/liter as a categorical independent variable (≥6.87 or <6.87 AUC0-24) in a univariable logistic regression analysis demonstrated a significant relationship with nausea/vomiting (P = 0.00033; odds ratio, 3.25 [95% CI, 1.73, 6.09]; McFadden's ρ2 = 0.0426).

When other patient characteristics were examined as predictors of nausea/vomiting, only sex and alcohol use were found to be significant. Based on univariable logistic regression, sex was associated with nausea/vomiting, with females having a higher probability of nausea/vomiting (P = 0.00022; odds ratio for females, 2.92 [95% CI, 1.63, 5.24]; McFadden's ρ2 = 0.0450). Additionally, the absence of alcohol use was associated with a lower probability of nausea/vomiting (P = 0.0185; odds ratio when alcohol use is absent, 6.35 [95% CI, 0.84, 48.2]; McFadden's ρ2 = 0.0183).

Using multivariable logistic regression with backward stepping, only sex and AUC0-24 (categorized based on the above-described CART-derived threshold) were found to be significant predictors of nausea/vomiting. When evaluated as a continuous variable, AUC0-24 failed to demonstrate significance. Only sex remained in the model. The final multivariable logistic regression model, with both sex and AUC0-24 evaluated as categorical variables, is shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Final multivariable logistic regression model for factors predictive of nausea/vomiting, with sex and AUC0-24 as categorical variablesa

| Parameter | Estimate | Odds ratio (95% confidence intervals) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexb | 0.895 | 2.45 (1.34, 4.47) | 0.00414 |

| AUC0-24 thresholdc | 0.955 | 2.60 (1.35, 4.99) | 0.00358 |

McFadden's ρ2 = 0.0712.

The reference group included males. The odds ratio presented is for females versus males.

The reference group included patients with AUC0-24 of <6.87 mg · h/liter. The odds ratio presented is for an AUC0-24 of ≥6.87 versus an AUC0-24 of <6.87 mg · h/liter.

Of the 289 patients evaluated for the safety analysis cohort, a total of 270 and 108 patients had the necessary data to examine maximum change from baseline in total bilirubin and BUN, respectively. Univariable linear regression demonstrated that increases in AUC0-24 were significantly associated with larger maximum changes in total bilirubin (P < 0.001). However, as evidenced by the shallowness of the slope of the effect (an increase in maximum change in bilirubin of 0.046 mg/dl per 1-mg · h/liter increase in AUC0-24) and the size of the adjusted r2 value (0.053), the magnitude of impact was not very impressive. The only other variable that was significant in the multivariable model was baseline bilirubin. When baseline bilirubin was added to the model, the overall adjusted r2 improved to 0.62 and the significance of the effect of the AUC0-24 remained. However, the slope of the effect of AUC0-24 still was very shallow (an increase in maximum change in bilirubin, adjusted for baseline bilirubin, of 0.022 mg/dl per 1-mg · h/liter increase in AUC0-24). Relationships for the other potential predictors (demographics and disease characteristics) failed to show any trends when examined graphically. Neither AUC0-24 nor any of the other independent variables evaluated were significantly associated with maximum change in BUN.

DISCUSSION

In the analyses described herein, we failed to identify a relationship between tigecycline exposure, as measured by the fAUC0-24:MIC ratio, and response categorized dichotomously as success or failure at the test-of-cure visit. Reasons for not identifying an exposure-response relationship for efficacy include the following: (i) insufficient numbers of events (in the present circumstance, failures); (ii) the exposures observed for patients were in the upper, flat portion of an exposure-response relationship curve; (iii) the endpoint (success or failure at the test-of-cure visit) was too insensitive to capture the drug's benefit; and (iv) there was no exposure-response relationship (i.e., the drug lacks benefit) (1).

It is likely that our failure to identify an exposure-response relationship for efficacy in this analysis was due to the first of these reasons. In the current data set, only 7% (5/68) were categorized as microbiological treatment failures. Clearly, our ability to discern a meaningful exposure-response relationship based upon a dichotomous efficacy endpoint was affected by the high tigecycline response rate.

The low number of failures could be due to the tigecycline exposures in patients (fAUC0-24:MIC ratios) that lie on the upper, flat portion of an exposure-response curve. Data derived from preclinical infection models and clinical data described herein support this hypothesis. In PK-PD studies conducted in neutropenic mice challenged with S. pneumoniae, tigecycline AUC0-24:MIC ratios associated with net bacterial stasis and a 90% reduction in bacterial burden were 0.1 and 1, respectively (8). The median (minimum, maximum) of fAUC0-24:MIC for the 68 patients described here was 11.1 (1.04, 35.9).

Given the relatively large drug exposures observed in patients relative to those necessary for efficacy in neutropenic animal infection models, it is possible that success or failure determined at the test-of-cure visit was too insensitive an endpoint to capture the treatment benefit of tigecycline. One way to test this hypothesis is to consider continuous numeric endpoints, such as time to fever resolution. In the present analysis, time to fever resolution was related to drug exposure. Fever in patients with tigecycline fAUC0-24:MIC ratios of >12.8 resolved faster (median difference, 12 h; P = 0.05) than fever in patients with lesser drug exposures. Given the limited number of failures in the current data set, the large drug exposures observed in patients relative to those effective in animal infection models and the detection of a relationship between drug exposure and time to fever resolution, it is likely that the failure to identify an exposure-response relationship for a categorical outcome at the test-of-cure visit was due to the insensitivity of this endpoint.

With the larger data set available for the safety analyses, the opportunity to identify an exposure-response relationship was enhanced. A significant relationship between tigecycline exposure and the occurrence of nausea and/or vomiting was found. Patients with an AUC0-24 value greater than or equal to 6.87 had nearly three times the risk of experiencing nausea and/or vomiting than those patients with an AUC0-24 value below this threshold. Although the relationship between AUC0-24 as a continuous variable and adverse event occurrence was not significant in the multivariable model, the concordance between the univariable point estimate for risk and that found in an analysis of data from healthy volunteers conducted by Passarell et al. (5) is interesting. In the CAP patients described herein, there was a 17% increase in risk with every unit increase in the AUC0-24. In the previous analysis, there was an 18.6% increase in the risk of nausea with every unit increase in the AUC0-24 (5).

A significant relationship also was found between exposure and maximum change from the baseline in total bilirubin. Despite the extremely low P value, three factors contribute to the conclusion that this relationship is not clinically significant. First, the range of change in bilirubin was narrow, and very few patients had increases that would be considered clinically meaningful. Second, the magnitude of the effect of the AUC0-24 (as expressed by the slope of the linear regression line) was minimal, such that every 1-mg · h/liter increase in AUC0-24 was associated with an increase in a maximum change in bilirubin of only 0.046 mg/dl. Finally, the adjusted r2 for the univariable linear regression model was only 0.053, suggesting that variability in the AUC0-24 explains a small portion of the variability in the maximum change in bilirubin.

In summary, in these analyses we demonstrated relationships between tigecycline exposure and efficacy and safety endpoints. For efficacy, we demonstrated that for patients for whom fAUC0-24:MIC ratios of >12.8 were attained, fever resolved faster than it did for those patients with lesser drug exposures. For safety, a multivariable logistic regression model was constructed in which the tigecycline AUC above a threshold of 6.87 mg · h/liter and female sex were predictive of the occurrence of nausea and/or vomiting. Although statistically significant, the linear relationship between tigecycline exposure and maximum change from baseline in total bilirubin is unlikely to be clinically significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by Wyeth Research, which was acquired by Pfizer, Inc., in October 2009. Sujata M. Bhavnani, Christopher M. Rubino, Alan Forrest, and Paul G. Ambrose were employees of the Institute for Clinical Pharmacodynamics, Ordway Research Institute, which was a paid consultant to Pfizer during the conduct of this study and development of the manuscript. The Institute for Clinical Pharmacodynamics became independent of Ordway Research Institute in July 2010. Joan Korth-Bradley, Angel Cooper, Nathalie Dartois, and Gary Dukart are employees of Pfizer, Inc.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 October 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Ambrose PG. 2008. Use of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in a failure analysis of community-acquired pneumonia: implications for future clinical trial study design. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47:S225–S231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carney S, Butcher RA, Dawborn JK, Pattison G. 1974. Minocycline excretion and distribution in relation to renal function in man. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1:299–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Meagher AK, et al. 2007. Exposure-response analyses of tigecycline efficacy in patients with complicated skin and skin-structure infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1939–1945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Passarell JA, et al. 2008. Exposure-response analyses of tigecycline efficacy in patients with complicated intra-abdominal infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:204–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Passarell JA, et al. 2005. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model for the tolerability of tigecycline in healthy volunteers. 15th Eur. Cong. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., abstr. P894 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rubino CM, et al. 2010. Tigecycline population pharmacokinetics in patients with community- or hospital-acquired pneumonia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:5180–5186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tanaseanu C, et al. 2008. Integrated results of 2 phase 3 studies comparing tigecycline and levofloxacin in community-acquired pneumonia. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 61:329–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Ogtrop ML, et al. 2000. In vivo pharmacodynamic activities of two glycylcyclines (GAR-936 and WAY 152,288) against various gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:943–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc 2011. Tygacil (tigecycline) for injection. Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]