Abstract

Infections and thromboses are the most common complications associated with central venous catheters. Suggested strategies for prevention and management of these complications include the use of heparin-coated catheters, heparin locks, and antimicrobial lock therapy. However, the effects of heparin on Candida albicans biofilms and planktonic cells have not been previously studied. Therefore, we sought to determine the in vitro effect of a heparin sodium preparation (HP) on biofilms and planktonic cells of C. albicans. Because HP contains two preservatives, methyl paraben (MP) and propyl paraben (PP), these compounds and heparin sodium without preservatives (Pure-H) were also tested individually. The metabolic activity of the mature biofilm after treatment was assessed using XTT [2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide] reduction and microscopy. Pure-H, MP, and PP caused up to 75, 85, and 60% reductions of metabolic activity of the mature preformed C. albicans biofilms, respectively. Maximal efficacy against the mature biofilm was observed with HP (up to 90%) compared to the individual compounds (P < 0.0001). Pure-H, MP, and PP each inhibited C. albicans biofilm formation up to 90%. A complete inhibition of biofilm formation was observed with HP at 5,000 U/ml and higher. When tested against planktonic cells, each compound inhibited growth in a dose-dependent manner. These data indicated that HP, MP, PP, and Pure-H have in vitro antifungal activity against C. albicans mature biofilms, formation of biofilms, and planktonic cells. Investigation of high-dose heparin-based strategies (e.g., heparin locks) in combination with traditional antifungal agents for the treatment and/or prevention of C. albicans biofilms is warranted.

INTRODUCTION

Central venous catheters (CVCs) are commonly used, particularly in critically ill patients. Infections and thromboses are the most common complications associated with CVCs, resulting in increased mortality rates and cost of care. Candida species are now the fourth most common cause of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections. Despite advances in antifungal therapy, the high attributable mortality rate due to Candida infections has not clearly improved in the last 2 decades.

Biofilm formation is a key pathogenic attribute of Candida albicans that enhances its ability to adhere to surfaces and cause disease in humans (11). Biofilm formation represents a major challenge for the treatment of biomaterial-related Candida infections. However, in many critically ill patients with biomaterial- or catheter-related Candida infection, removal and/or replacement of the infected device is difficult or high risk.

In addition to standard antifungal therapy, numerous strategies have been proposed for the conservative management of CVC-associated complications, including the use of antibiotic lock therapy, heparin locks, and heparin-coated catheters (8). The anticoagulant properties of heparin are widely known. In addition, early reports have suggested that heparin has antibacterial properties against some bacterial species (12, 18). More recently however, Shanks et al. have reported on the ability of heparin to stimulate Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation in vitro (14). The use of systemic heparin has also been identified as a risk factor for catheter-related sepsis in dialysis patients (4).

The effects of heparin on C. albicans biofilms and planktonic cells have not been investigated. We present a detailed analysis of the in vitro effects of a standard clinical preparation of heparin sodium (up to 10,000 U/ml) on biofilms and planktonic cells of C. albicans. Five different strains of C. albicans were tested. We also conducted an analysis of each individual compound contained in this heparin sodium preparation (heparin sodium, methyl paraben [MP], and propyl paraben [PP]).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and reagents used.

Five C. albicans strains derived from clinical isolates were used throughout the study. The clinically derived wild-type strain C. albicans SC5314 was used as a reference isolate. The ATCC 10231, ATCC 14053, and ATCC 24433 strains of C. albicans and a C. albicans FKS1 mutant (strain 42379) characterized by echinocandin resistance were also used (7, 17). Strains were routinely grown at 30°C in YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) supplemented with uridine (80 μg ml−1). For biofilm studies, cells were resuspended at a density of 1 × 106 cells ml−1 in RPMI 1640 supplemented with l-glutamine (US Biological, Swampscott, MA) and buffered with 165 mM MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) to pH 7.0. For studies on the effect of reagents on growth of planktonic cells, cells were resuspended in complete synthetic medium (0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids [YNB], 2% glucose, 0.079% complete synthetic mixture).

In this study, the activity of a standard clinical heparin sodium preparation (HP; Abraxis Pharmaceutical Products, LLC, Schaumburg, IL) (purchased from the hospital pharmacy) against C. albicans biofilms was examined. This 20,000-U/ml preparation (HP) contains 20,000 porcine heparin units, 0.15% methyl paraben, and 0.015% propyl paraben. As a reference, this preparation is defined to be the stock concentration of “20×”. The individual components, methyl paraben (MP), propyl paraben (PP), and heparin without preservatives (heparin sodium salt from porcine intestinal mucosa; Pure-H) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Studies thus included the evaluation of the effect of HP, MP, PP, and Pure-H, at concentrations ranging from 1× to 10×, on mature (preformed) biofilms, formation of biofilms, and growth of planktonic C. albicans.

Biofilm studies.

The effects of HP, MP, PP, and Pure-H on mature biofilms and biofilm formation were assessed using the XTT [2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide] reduction assay in a 96-well static microplate model as described by Ramage and Lopez-Ribot (9). Briefly, mature biofilms were incubated for 24 h with increasing dilutions of each reagent prepared in RPMI 1640 medium. The resulting metabolic activity was then measured using the XTT reduction assay (9). Experiments were performed three times independently, each in quadruplicate. For studies on biofilm formation, planktonic cells were resuspended at a density of 1 × 106 cells ml−1 in RPMI 1640 medium containing the reagent to be tested, dispensed in quadruplicate into wells of a 96-well microtiter plate, and then incubated at 37°C for 24 h before biofilm mass was assessed. Experiments on biofilm formation were performed once, each in quadruplicate. Biofilm mass was assessed in relation to metabolic activity measured using the XTT reduction assay (9).

Growth curves.

The effect of each reagent on the growth of planktonic C. albicans SC5314 cells was also assessed. Growth was assessed in liquid medium by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) at fixed intervals. Cells from overnight cultures were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (1× PBS) and then resuspended in fresh complete synthetic medium to a starting OD600 of 0.1 (which corresponds to a cell density of approximately 1 × 106 cells/ml). Strains grown in complete synthetic medium were also exposed to increasing dilutions of HP, MP, PP, and Pure-H. Four-hundred-microliter cultures were grown in quadruplicate in a microtiter plate at 37°C for 30 h in an automated Bioscreen C Analyzer (Thermo Labsystems). Shaking of the microcultures was performed at high intensity with irregular rotation every 3 min for 20 s, and optical densities at a λ of 600 nm were measured every half hour. Growth curves were generated using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Additionally, dose-response curves were generated by plotting the resulting OD600 at 24 h against the log of the concentration of the reagent tested. The concentration at which growth of planktonic cells is inhibited by 50% was then estimated using nonlinear regression approximations in GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Light and scanning electron microscopy.

Light micrographs of the biofilms formed in the presence of each test reagent were acquired using an inverted microscope (Micromaster digital inverted microscope with Infinity optics; Fisher Scientific) and data acquisition software (Micron 2.0.0; Westover Scientific). Sample preparation for scanning electron microscopy was performed on biofilm samples formed on a coverslip (Thermanox; Nalge Nunc International) after 24 h of incubation of a 0.5-ml inoculum containing 1 × 106 cells ml−1 in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with defined concentrations of each compound included in this study, as previously described (10). Scanning electron micrographs were obtained using a Hitachi S-800 scanning electron microscope set at 20 kV, with images acquired using Quartz PCI software (Hitachi High Technologies America, Inc., Pleasanton, CA).

Definitions.

Enhanced (synergistic) activity was defined to be present if the effect of HP (which contains all 3 compounds) was a statistically significant reduction in metabolic activity compared to when the individual compounds were used alone (P < 0.05). The effect was considered indifferent if HP caused a reduction in metabolic activity compared to the effect of either agent alone and the reduction was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Statistical analyses.

We compared the resulting metabolic activities of the treatment groups and controls using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey's multiple-comparison posttest. Differences between groups were considered to be significant at a P value of <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Effects of heparin and parabens on mature Candida albicans biofilms.

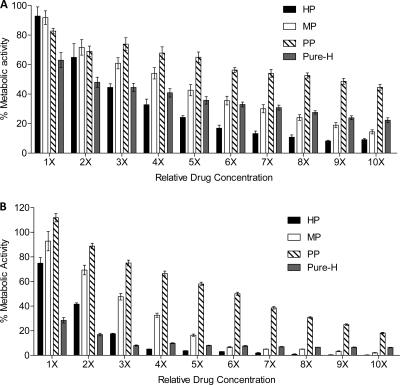

All compounds were tested individually for activity against mature (preformed) biofilms from five strains of C. albicans, including 4 ATCC strains and 1 echinocandin-resistant clinical isolate. The clinical strain C. albicans SC5314 was used as the reference isolate. In general, each agent affected the mature biofilm in a dose-responsive manner (Fig. 1A). For all strains tested, a concentration of 1× HP caused a mean reduction in biofilm metabolic activity of 12.9% (Fig. 2; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In comparison, when tested as single agents, a 1× concentration of MP or PP achieved reductions of 1.9% and 7.6% in biofilm metabolic activity, respectively (Fig. 2; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Over increasing concentrations, mean MP activity was greater than mean PP activity. At a concentration of 1×, Pure-H had the greatest overall reduction against preformed biofilms compared to the other tested agents, with a reduction of 30 to 50% in metabolic activity (Fig. 2; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Fig 1.

In vitro effects of heparin sodium preparation and individual reagents against mature biofilms of and formation of biofilms by C. albicans reference strain SC5314. (A) Effect of each reagent tested on mature biofilms formed by the reference clinical strain SC5314. (B) Effect of each reagent tested on biofilm formation by strain SC5314. Biofilm metabolic activity was assessed using the XTT assay. HP, heparin preparation; MP, methyl paraben; PP, propyl paraben; Pure-H, pure heparin.

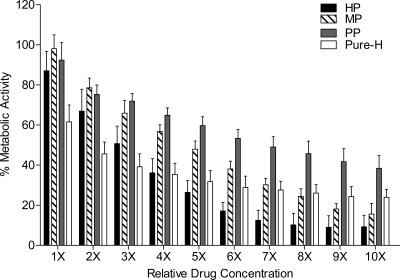

Fig 2.

In vitro effects of the heparin sodium preparation and individual reagents against mature C. albicans biofilms. Mature biofilms were incubated with RPMI 1640 containing serial dilutions (1× to 10×) of each reagent as indicated. The mean effect of each reagent tested on mature biofilms formed by strains SC5314, ATCC 10231, ATCC 14053, and ATCC 24433 and the echinocandin-resistant strain 42379 is shown. Biofilm metabolic activity was assessed using the XTT assay. HP, heparin preparation; MP, methyl paraben; PP, propyl paraben; Pure-H, pure heparin. The effect of each reagent tested on mature biofilms formed by each strain can be found in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

With increasing concentrations of Pure-H, the greatest reduction effected by Pure-H was only 76% even at the maximal concentration tested. In contrast, there was up to a 90% reduction in biofilm metabolic activity of the preformed biofilms of the wild-type strains when treated with HP (at >6×) (Fig. 2). In comparison, at a concentration of 10×, MP resulted in an 85 to 95% reduction in biofilm metabolic activity (Fig. 2; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Treatment with 10× PP resulted in a mean reduction of 61.6% (Fig. 2). It should be noted, however, that 10× PP is equivalent in final concentration to 1× MP, thus indicating that PP has greater activity than MP at the same concentration (percent, weight/volume) against the preformed biofilms of the C. albicans strains tested.

Using nonlinear regression analyses, we calculated the concentration of each reagent needed to reduce the biofilm (sessile) metabolic activity by 50% (SMIC50) in order to directly compare the effectiveness of each reagent against mature biofilms. The SMIC50s are 1,694 U/ml, 0.027% (wt/vol), 0.005% (wt/vol), and 2,477 U/ml for Pure-H, MP, PP, and HP, respectively.

Effect of heparin and parabens on the formation of Candida albicans biofilms.

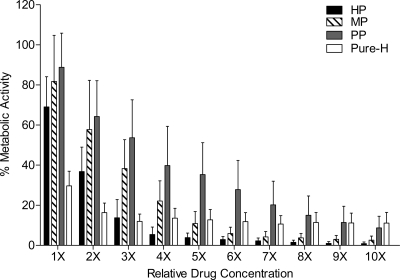

Next we sought to characterize the ability of each compound (and combination) to suppress formation of C. albicans SC5314 biofilms. Inhibition of biofilm formation began at the lowest concentrations tested. Specifically, the resulting mass of biofilm formed in the presence of any compound was reduced compared to the biofilm mass formed in the absence of heparin and/or parabens (Fig. 1B, P < 0.0001). For all five C. albicans strains, heparin without preservatives (Pure-H) inhibited biofilm formation up to 89.4% (Fig. 3; see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The parabens, MP and PP, inhibited biofilm formation up to 97.4% and 91.3%, respectively (Fig. 3; see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Fig 3.

In vitro effects of heparin sodium preparation and individual reagents against C. albicans biofilm formation. Planktonic cells were resuspended at a density of 1 × 106 cells ml−1 in RPMI 1640 medium containing serial dilutions (1× to 10×) of each reagent as indicated. The mean effect of each reagent tested on biofilm formation by strains SC5314, ATCC 10231, ATCC 14053, and ATCC 24433 and the echinocandin-resistant strain 42379 is shown. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, the metabolic activity of the biofilm that was formed was assessed using the XTT assay. HP, heparin preparation; MP, methyl paraben; PP, propyl paraben; Pure-H, pure heparin. The effect of each reagent tested on biofilm formation of each strain can be found in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material.

HP (containing MP, PP and Pure-H) showed almost complete inhibition of biofilm formation at concentrations of 5,000 U/ml and higher (Fig. 3). Compared to the effect of these compounds on mature biofilms, lower concentrations of each compound are required to inhibit the formation of biofilm. Using nonlinear regression analyses of dose-response curves for HP and the individual components, the concentration of Pure-H, MP, PP, and HP needed to inhibit biofilm formation by 50% (SMIC50) are 452 U/ml, 0.021% (wt/vol), 0.004% (wt/vol), and 1787 U/ml, respectively. While the calculated SMIC50 of Pure-H is lower than HP, at higher concentrations, HP was more effective in the prevention of biofilm formation (almost 100%).

Structural analysis of Candida albicans biofilm formation.

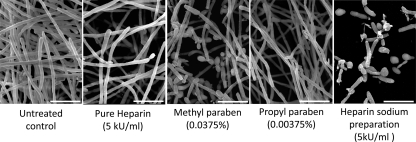

The effects of heparin and parabens on formation of C. albicans SC5314 biofilms were examined using light microscopy at all concentrations tested. Although it was not possible to visually quantify the numbers of cells intertwined as filaments within a biofilm, we observed a clear reduction in the aggregate microscopic cell density with increasing concentrations of each reagent, with the greatest reduction seen for the HP preparation (data not shown). The reduction in biofilm mass seen directly through microscopic observations appeared to correspond to the quantitative XTT assay results. In order to gain a detailed understanding of biofilm structure after treatment with HP and each individual compound, we next selected a concentration of 5× of each reagent for ultrastructural examination using scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 4). This concentration correlates with 5,000 units of subcutaneous sodium heparin, which is typically used for deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis or as a heparin lock used in hemodialysis catheters. For each reagent tested, there was a clear reduction in biofilm density, with the greatest reduction in the biofilm treated with the HP preparation, compared to that of the untreated control (Fig. 4). Interestingly, in the MP-treated biofilm, some of the cells appeared to be predominantly pseudohyphal or yeast form. After treatment with the HP preparation, we observed fewer filamentous elements, which were characterized by truncated and distorted filaments, than in the untreated control biofilm. Yeast and pseudohyphal forms were evident as well.

Fig 4.

Structural effects of heparin and parabens on biofilm formation. Sample preparation for scanning electron microscopy was performed on biofilm samples formed on a coverslip after 24 h of incubation of a 0.5-ml inoculum containing 1 × 106 cells ml−1 in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with a standard clinical concentration of 5× of each compound (HP, PP, MP, and Pure-H). The bars indicate 15 μm.

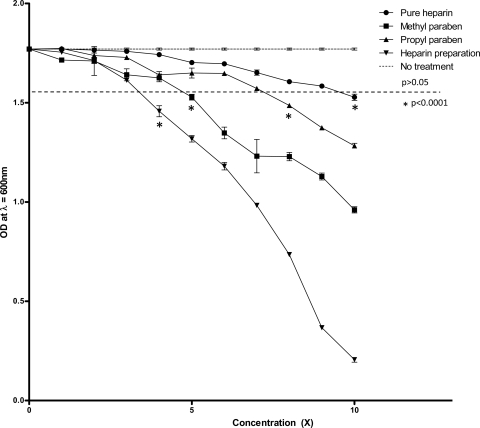

Effects of heparin and parabens against planktonic cells.

We next tested the effect of each reagent against C. albicans SC5314 planktonic cells grown in liquid microcultures. Each compound inhibited growth in a dose-dependent manner, with the greatest antifungal effect seen in the heparin sodium preparation (HP) (Fig. 5). However, for each concentration tested, the degree to which growth of planktonic cells was inhibited was not comparable to either the inhibition of biofilm formation or the decrease in metabolic activity of the mature biofilms. Much higher concentrations of each individual reagent were required to inhibit the growth of planktonic cells than to inhibit the formation of biofilms. Specifically, 22,538 U/ml, 0.08% (wt/vol), 0.01% (wt/vol), and 7,901 U/ml of Pure-H, MP, PP, and HP, respectively, inhibited growth of C. albicans yeast cells by 50%. These results suggest that the effects of each reagent on mature biofilm and the formation of biofilm are not solely due to the inhibition of growth of planktonic cells but rather are due to a direct effect on the biofilm.

Fig 5.

Dose-response curve of C. albicans planktonic cultures with heparin and parabens. The effect of each reagent on the growth of planktonic C. albicans SC5314 cells was assessed in liquid medium by measuring the OD600 at fixed intervals. Strains grown in complete synthetic medium supplemented with uridine were exposed to increasing dilutions of HP, MP, PP, and Pure-H (1× to 10×). Each dose-response curve indicates the final OD600 at stationary phase (24 h) for each concentration of reagent being tested. The horizontal dashed line indicates the points at which statistical significant deviation from the no-treatment control group occurs (P < 0.0001). This experiment was performed independently three times.

DISCUSSION

Heparin is widely used in daily clinical practice to treat and prevent thromboses. Heparin flushes, antibiotic lock solutions containing heparin, and heparin locks are currently used strategies for the prevention and treatment of CVC-associated thrombosis. Our findings demonstrate that a commonly used clinical sodium heparin preparation (Abraxis Pharmaceuticals) inhibits C. albicans mature biofilms, the formation of C. albicans biofilms, and planktonic cell growth. We showed that high concentrations of HP have a profound effect on biofilm formation and the growth of the yeast form of cells in traditional liquid culture.

Early reports suggest that heparin sodium without preservatives may suppress growth of some microorganisms, including Escherichia coli, S. aureus, and C. albicans (2, 3, 5, 12). In these studies, growth of single strains was variable depending on the ability of the microorganisms to grow in media with or without heparin (3, 12). Similar to our results, the growth of C. albicans was not inhibited in the presence of 1,000 U/ml heparin (5). Shanks et al. recently reported on the stimulating effect of heparin on Staphylococcus aureus biofilms (14). However, very low concentrations of heparin (from 0.01 to 1,000 U/ml) were used in the study, in contrast to the much higher concentrations used in current clinical practice (5, 12, 14). In the present study, we tested heparin over a range from 1,000 U/ml to the maximum dose of 10,000 U/ml. Our study demonstrated that heparin without a preservative (Pure-H) inhibits biofilm formation at all tested concentrations. This effect was seen in all 5 C. albicans strains tested, including the echinocandin-resistant clinical isolate with a known “hot spot” mutation in the FKS1 gene (17). Thus, this heparin effect against C. albicans biofilms was generalized and not strain specific. Interestingly, this effect was less pronounced in the planktonic cells, where a larger dose of heparin (and/or parabens) was required for inhibition, than for the inhibition of biofilm formation. These data suggest that the heparin and paraben activity against formation of C. albicans biofilms is a result of more than just an antifungal effect alone. As might be predicted, the highest concentrations of agents were needed to inhibit fully formed, mature C. albicans biofilms. A possible explanation of the antimicrobial effect of heparin may be that heparin interferes with the utilization of ammonia by certain microorganisms (3). In addition, Andersson et al. showed that C. albicans exhibits marked sensitivity to heparin-binding peptides occurring in the host (1). However, the specific mechanism of heparin activity against C. albicans remains unknown, although interestingly, it has been reported that C. albicans expresses putative heparin-binding domains (6).

Most clinically available heparin solutions contain preservatives. In the present study, we used a commonly used, commercially available, FDA-approved heparin sodium preparation (from Abraxis Pharmaceuticals) which contains 20,000 U/ml heparin sodium salt from porcine intestinal mucosa and a mixture of two parabens (0.15% [wt/vol] MP and 0.015% [wt/vol] PP). Parabens have been widely used as preservatives in the cosmetic, pharmaceutical, and food industries. Propyl paraben and methyl paraben are esters of para-hydroxybenzoic acid with reported antifungal activity (15). Indeed, our study showed that PP reduces the metabolic activity of mature biofilm by up to 61.6% and inhibits biofilm formation by up to 91.3% (Fig. 2 and 3). The activity of these parabens was seen in all 5 C. albicans strains, including the echinocandin-resistant clinical isolate, thus demonstrating that this effect was not strain specific.

In a recent study, Steczko et al. reported on the antimicrobial properties of a multicomponent lock solution using citrate-methylene blue and methyl and propyl paraben (16). The authors concluded that the proposed multicomponent lock solution has strong antimicrobial properties against both planktonic and sessile microorganisms, including C. albicans. By comparison, heparin with preservatives (2,500 U/ml heparin with 0.0375% MP and 0.00375% PP) showed weaker antimicrobial properties (16). However, the effects of single agents (MP, PP, or Pure-H) on C. albicans biofilms were not tested. Scott et al. reported on the synergistic effect of the combination of fluconazole and propyl paraben on the growth of C. albicans planktonic cells (13). In their study, the combination of both agents caused a reduction of up to 70% in yeast growth. The authors hypothesized that propyl paraben may have membrane activity by either facilitating the uptake of fluconazole or enhancing the membrane damage associated with the azole exposure.

We demonstrated that the combination of high concentrations (5× or greater) of Pure-H, MP, and PP in the proportions contained in heparin sodium solution has a synergistic effect on C. albicans SC5314 mature biofilms. Comparable results were found in all five C. albicans strains tested (including an echinocandin-resistant isolate), indicating that these results are reproducible and not strain specific. These findings to our knowledge have not been previously reported. Thus, investigation of high-dose-heparin-based strategies (e.g., heparin locks) in combination with traditional antifungal agents for the treatment and/or prevention of C. albicans biofilms is warranted.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank William Fonzi (Georgetown University) for providing strain SC5314. We thank Stephen Jett (University of New Mexico) for assistance with the scanning electron microscopy at the UNM Health Sciences Center Electron Microscopy Facility.

S.A.L. reports ownership of Pfizer common stock (240 shares).

This work was supported in part by grants from the Department of Veterans' Affairs (MERIT Award to S.A.L.) and the Biomedical Research Institute of New Mexico (to S.A.L.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 10 October 2011

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aac.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andersson E, et al. 2004. Antimicrobial activities of heparin-binding peptides. Eur. J. Biochem. 271:1219–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Christman JF, Doherty DG. 1956. Microbial utilization of heparin. J. Bacteriol. 72:429–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Christman JF, Doherty DG. 1956. The antimicrobial action of heparin. J. Bacteriol. 72:433–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Diskin CJ, Stokes TJ, Dansby LM, Radcliff L, Carter TB. 2007. Is systemic heparin a risk factor for catheter-related sepsis in dialysis patients? An evaluation of various biofilm and traditional risk factors. Nephron Clin. Pract. 107:c128–c132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ferguson RL, Rosett W, Hodges GR, Barnes WG. 1976. Complications with heparin-lock needles. A prospective evaluation. Ann. Intern. Med. 85:583–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gale CA, et al. 1998. Linkage of adhesion, filamentous growth, and virulence in Candida albicans to a single gene, INT1. Science 279:1355–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gillum AM, Tsay EY, Kirsch DR. 1984. Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyrF mutations. Mol. Gen. Genet. 198:179–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mermel LA, et al. 2001. Guidelines for the management of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:1249–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ramage G, Lopez-Ribot JL. 2005. Techniques for antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida albicans biofilms. Methods Mol. Med. 118:71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ramage G, Saville SP, Wickes BL, Lopez-Ribot JL. 2002. Inhibition of Candida albicans biofilm formation by farnesol, a quorum-sensing molecule. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5459–5463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramage G, Saville SP, Thomas DP, Lopez-Ribot JL. 2005. Candida biofilms: an update. Eukaryot. Cell 4:633–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosett W, Hodges GR. 1980. Antimicrobial activity of heparin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 11:30–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scott EM, Tariq VN, McCrory RM. 1995. Demonstration of synergy with fluconazole and either ibuprofen, sodium salicylate, or propylparaben against Candida albicans in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2610–2614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shanks RM, et al. 2005. Heparin stimulates Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 73:4596–4606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sokol H. 1965. Evaluation of a new reagent determining the fertility period (“Fertility-Tape”). Pol. Tyg. Lek. 20:1114–1116 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Steczko J, Ash SR, Nivens DE, Brewer L, Winger RK. 2009. Microbial inactivation properties of a new antimicrobial/antithrombotic catheter lock solution (citrate/methylene blue/parabens). Nephrol. Dial Transplant. 24:1937–1945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wiederhold NP, Grabinski JL, Garcia-Effron G, Perlin DS, Lee SA. 2008. Pyrosequencing to detect mutations in FKS1 that confer reduced echinocandin susceptibility in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:4145–4148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zappala C, Chandan S, George N, Faoagali J, Boots RJ. 2007. The antimicrobial effect of heparin on common respiratory pathogens. Crit. Care Resusc. 9:157–160 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.