Abstract

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH) is a rare, benign cutaneous lesion characterized histologically by a proliferation of eccrine glands and vascular structures—generally capillaries—in the middle and deep dermis. Sudden enlargement of EAH lesions with or without pain has been noted during puberty and pregnancy and has been attributed to hormonal stimulation. We herein describe a case of EAH that became symptomatic in an adolescent girl. A 13-year-old girl presented with pain associated with a sudden enlargement of a previously asymptomatic swelling on her right second toe. She had an 8-year history of an asymptomatic swelling on her right second toe, and the symptoms appeared approximately 1 year after menarche. Physical examination revealed swelling of the plantar surface of her right second toe. The overlying surface was erythematous with a small amount of fine scales. The biopsied tissue showed a nodular proliferation of eccrine glands intimately admixed with numerous small vessels in the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat tissue. Mucin deposition was present in the stroma surrounding the proliferating eccrine coils and ducts and in the upper dermis. A diagnosis of EAH was made. We suggest that hormonal changes during puberty may have played a role in the rapid growth and pain in the present case.

Keywords: eccrine angiomatous hamartoma, hyperhidrosis, menarche, mucin, pain

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH) is a rare, benign cutaneous lesion characterized histologically by a proliferation of eccrine glands and vascular structures in the dermis.1–4 It usually arises at birth or during early infancy and childhood as a nodule or a plaque predominantly involving the distal extremities. Although some EAH cases are asymptomatic, pain and hyperhidrosis are common. Sudden enlargement of EAH lesions with or without pain has been noted during puberty1,3,5 and pregnancy.6 Here, we describe a case of EAH on the right second toe of an adolescent girl. Although the EAH lesion has been asymptomatic for 7 years since its appearance when she was 5 years old, it grew rapidly with pain approximately 1 year after menarche.

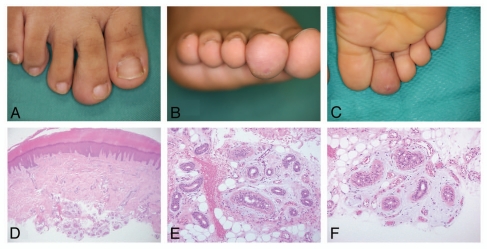

A 13-year-old Japanese girl had an 8-year history of a swelling on her right second toe. The swelling had been growing slowly until 5 months prior to presentation, when it began to grow rapidly and was associated with tenderness. She also began to feel pain when she stood for a long time. Sixteen days before presenting to our clinic, she had attended her junior high school athletic meet and the swelling became painful. Physical examination revealed swelling of the plantar surface of her right second toe (Fig. 1A–C). The overlying surface was erythematous with a small amount of fine scales (Fig. 1B and C). Although the patient reported an episode of hyperhidrosis of the affected toe, hyperhidrosis was not evident on examination. A skin biopsy showed acanthosis with hypertrophy of the granular layer, mild elongation of rete ridges and a mild, perivascular inflammatory infiltration in the superficial dermis (Fig. 1D). In the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat tissue, there was a proliferation of normally structured eccrine coils and ducts (Fig. 1E and F). Extravasation of erythrocytes was also noted around the eccrine glands (Fig. 1E). There was an abundant deposition of mucinous material in the stroma surrounding the proliferating eccrine coils and ducts (Fig. 1E and F). Proliferation of small capillary-sized vessels was observed in some areas of the stroma in subcutaneous fat tissues (Fig. 1F). The mucinous material in the stroma was confirmed as mucin by Alcian blue stain (data not shown). Mucin deposition was also present in the upper dermis (data not shown). Immunohistochemical examination showed that the eccrine coils and ducts were stained positively for CEA, S-100 and EMA (data not shown). A diagnosis of EAH was made. Several painful skin tumors and malformations (Table 1) were ruled out based on histological findings. We plan to excise the lesion if the pain becomes severe.

Figure 1.

Clinical appearance of the skin lesion. (A–C) Swelling of the plantar surface was apparent on the right second toe. The overlying surface was erythematous with a small amount of fine scales. Histologically, the epidermis showed acanthosis with hypertrophy of the granular layer and mild elongation of rete ridges. (D) A mild, perivascular inflammatory infiltration in the upper dermis was seen (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification x40). (E) A nodular proliferation of normally structured eccrine coils and ducts in the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat tissue. Some of the ducts show mild dilation. Extravasation of erythrocytes was also noted around the proliferation of eccrine glands (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification x200). (F) Proliferation of small capillary-sized vessels in the stroma surrounding the eccrine glands in the subcutaneous fat tissues (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification x200).

Table 1.

Painful skin tumors/malformations

| Disease | Age | Sex | Common sites | Clinical findings | Histology |

| Angioleiomyoma | Fourth to sixth decades of life | Women > Men | Lower extremities | Subcutaneous nodule | Encapsulated lesion containing numerous veins with muscular walls (S**) |

| Angiolipoma | Fourth to sixth decades of life | Men > Women | Forearms | Subcutaneous nodule | Encapsulated lesion containing mature adipose tissue and blood vessels (S) |

| Eccrine angiomatous hamrtoma | Childhood | Women > Men | Extremities | Angiomatous nodule or red to violaceous plaque | Proliferation of eccrine glands and blood vessels (D***) |

| Eccrine spiradenoma | Second to fourth decades of life | Men = Women | Head, upper trunk | Intradermal nodule | Sharply demarcated lobules composed of two types of tumor cells ; undifferentiated cells with small, dark nuclei at the periphery and differentiating cells with large, pale nuclei in the center (D) |

| Glomus tumor | Fourth to sixth decades of life | Women > Men | Extremities, especially in the nail bed | Purple nodule | Encapsulated lesion containing vascular lumina and glomus cells (D) |

| Granular cell tumor | Fourth to sixth decades of life | Women > Men | Any part of the skin | Raised, firm nodule | A nested growth of large tumor cells with a pale cytoplasm filled with numerous fine granules (D) |

| Neurilemmoma | Third to fourth decades of life | Men = Women | Head and extremities | Subcutaneous nodule | Sharply demarcated lobules in the dermis. They are composed of two types of tumor cells; cells with small, dark nuclei at the periphery and cells with large, pale nuclei in the center (S) |

| Piloleiomyoma | Fourth to sixth decades of life | Men > Women | Head, upper extremities | Intradermal nodule | Interlacing bundles of smooth muscle fiberes (D) |

| Traumatic neuroma | Adult | ND* | Stump after amputation | Firm subcutaneous nodule | Sharply demarcated bundles of peripheral nerves (D) |

ND, information is lacking.

S, main lesion is located in the subcutaneous tissue.

D, main lesion is located in the dermis.

The natural course of EAH is enlargement commensurate with growth of the patient.7 Spontaneous regression has been observed in one case.8 EAH is a benign lesion and, as a rule, aggressive treatment is unnecessary if asymptomatic.1,2,9 Associated pain and cosmesis are the most common reasons for treatment of EAH.1,2,4 Localized, small lesions can be cured by simple local excision.1,2 However, some cases with severe pain required amputation6 or high doses of analgesics.10

Several mechanisms of pain and/or tenderness in EAH have been postulated. Electron microscopy revealed the presence of tubular structures infiltrating the neural sheaths of small dermal nerves,11 which were hypothesized to be a potential source of the pain. Sulica et al. suggested that the pain and tenderness may have resulted from swelling or compression of nerves by hamartomatous tissue, rather than actual proliferation of neural elements in the growth. In some cases, EAH lesions grew rapidly during puberty and pregnancy;1,3–6 thus, some authors suggested that the rapid growth and/or pain were caused by hormonal stimulation,6,7 although specific hormones have not been identified nor suggested. In one case, hormones related with menstrual cycle such as estrogen, progesterone, luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone are possible candidates for the responsible hormone(s). In addition, Gabrielsen et al. suggested that pain may occur due to fluid retention associated with pregnancy. In our case, although the cutaneous lesion had been asymptomatic for about seven years, pain and rapid growth occurred about one year after menarche, suggesting that hormonal change may have influenced the rapid growth and pain.

It has been postulated that the focal hyperhidrosis of EAH is an expression of its eccrine components.12,13 Botulinum toxin has been successfully used to treat the hyperhidrosis of EAH.14

To the best of our knowledge, fewer than 10 cases of EAH with mucin deposition have been reported. The main difference between the present case and previously reported cases is that there was mucin deposition not only in the stroma surrounding the eccrine glands and vascular structures but also in the superficial dermis in the present case.

References

- 1.Sulica RL, Kao GF, Sulica VI, Penneys NS. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (nevus): immunohistochemical findings and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:71–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1994.tb00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakatsui TC, Schloss E, Krol A, Lin AN. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of a case and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:109–111. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pelle MT, Pride HB, Tyler WB. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:429–435. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.121030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinelli PT, Tschen JA. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2003;71:449–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrell DS, Ghali FE, Stahr BJ, McCauliffe DP. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a report of symmetric and painful lesions of the wrists. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:117–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.018002117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabrielsen TO, Elgjo K, Sommerschild H. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma of the finger leading to amputation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991;16:44–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1991.tb00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larralde M, Bazzolo E, Boggio P, Abad ME, Santos Muñoz A. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of five congenital cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:316–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tay YK, Sim CS. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma associated with spontaneous regression. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:516–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.López V, Pinazo I, Santonja N, Jordá E. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:548–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf R, Krakowski A, Dorfman B, Baratz M. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. A painful step. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1489–1490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Challa VR, Jona J. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a rare skin lesion with diverse histological features. Dermatologica. 1997;155:206–209. doi: 10.1159/000251000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanmartin O, Botella R, Alegre V, Martinez A, Aliaga A. Congenital eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:161–164. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199204000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calderone DC, Glass LF, Seleznick M, Fenske NA. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:837–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1994.tb03716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barco D, Baselga E, Alegre M, Curell R, Alomar A. Successful treatment of eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with botulinum toxin. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:241–243. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]