Abstract

TCP4 and related members of class II TCP genes regulate leaf morphogenesis. We earlier demonstrated that level of TCP4 activity determines leaf size and aspects of plant maturity. The mechanism of TCP function and their target genes remain unidentified, limiting our understanding of TCP-mediated growth control. As leaf growth is influenced simultaneously by multiple phytohormones, we have studied if TCP4 interacts with any of the hormone-response pathways. Our analyses indicate a role for auxin, gibberellic acid and abscisic acid in TCP4-mediated control of leaf growth.

Key words: TCP4, leaf growth, GA, Auxin

Leaf size and shape are determined by spatial and temporal regulation of cell division and cell expansion. Members of class II TCP family of transcription factors regulate leaf morphogenesis1–3 by controlling the timing of proliferation to differentiation switch in a developing leaf.4 Loss of TCP function leads to bigger, crinkly leaves due to uncontrolled growth1,2 whereas enhanced TCP activity gives rise to smaller, cup-shaped leaves resulting from premature cessation of cell division.5 The mechanism of TCP activity and their downstream targets are poorly known.

Several phytohormones act independently, redundantly or interactively to affect many aspects of organ growth. Gibberellic acid (GA) and brassinosteroids (BR) are involved in cell division as well as expansion.6–9 Both auxin and cytokinin promote cell division during shoot growth.10,11 Abscisic acid (ABA) performs a major role in growth inhibition under stress, but ethylene can also induce cell cycle arrest in young leaves under osmotic stress.12,13 Since class II TCP proteins, such as TCP4, 2, 3, 10 and 24 in Arabidopsis, are negative regulators of leaf growth, we have investigated if these proteins modulate the function of any phytohormone to control leaf morphogenesis.

Transcriptional Profile of TCP4:VP16-C Significantly Overlaps with that of ABA, MeJA and Auxin-Treated Plants

We performed genome-wide transcript analysis to identify genes that are differentially-expressed in TCP4:VP16-C in comparison with tcp4-1.5 A total of 1,335 genes were identified, of which 581 were upregulated and 754 were downregulated (fold change ≥2). We compared these genes with the sets of genes that are regulated by seven phytohormones—auxin, GA, Brassinolide (an active BR), ABA, cytokinin, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC, a precursor of ethylene) and methyl jasmonate (MeJA).14 Results of this analysis are shown in Table 1. TCP4:VP16-C-upregulated genes overlapped with genes downregulated by ABA and MeJA, whereas, TCP4-VP16-C-downregulated genes overlapped with those upregulated by these two hormones, suggesting that hyperactivation of TCP4 produces an effect on the transcriptome that mimic the deficiency of ABA and MeJA. The antagonistic relationship between TCP4 and MeJA is unexpected as TCPs promote MeJA biosynthesis15 and TCP4:VP16-C plants display advanced senescence, a process controlled by MeJA.5 The analysis also revealed a similarity in transcriptome changes on auxin application and TCP4 activation. Interestingly, two auxin-induced small auxin-up RNA (SAUR) genes, At4g38850 (SAUR-AC1) and At5g18060, were upregulated ∼5- and ∼2.3-fold, respectively, in TCP4:VP16-C. Though the molecular function of SAURs is unknown, SAUR39 in rice negatively regulates auxin synthesis and transport.16 Further, a recent study has shown that TCP3 drives the expression of SAUR39 homolog in Arabidopsis.17 Thus, TCP4 activation is expected to downregulate auxin response. This is supported by the fact that TCP4:VP16-C leaves lack serrations, a marginal structure induced by auxin action.5 TCP4:VP16-C-downregulated genes showed overlap with those downregulated by ethylene, while cytokinin-upregulated genes overlapped with both TCP4:VP16-C upregulated and downregulated genes. We did not observe any significant overlap with GA- and BR-regulated genes.

Table 1.

Comparison of TCP4:VP16-C-regulated and hormone-responsive genes

| Number of genes upregulated by | Overlap with TCP4:VP16-C upregulated genes | Overlap with TCP4:VP16-C downregulated genes | |

| Abscisic acid | 1440 | 38 (37) | 128 (49)a |

| 1-amino-cyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid | 167 | 8 (4) | 5(6) |

| Brassinolide | 264 | 9 (7) | 15 (9) |

| Cytokinin | 332 | 33 (9)a | 24 (11)a |

| Auxin | 430 | 25 (11)a | 14 (15) |

| Methyl jasmonate | 806 | 20 (21) | 67 (27)a |

| Gibberellic acid | 40 | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Number of genes downregulated by | Overlap with TCP4:VP16-C upregulated genes | Overlap with TCP4:VP16-C downregulated genes | |

| Abscisic acid | 1476 | 100 (38)a | 52 (50) |

| 1-amino-cyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid | 365 | 11 (9) | 28 (12)a |

| Brassinolide | 383 | 18 (10) | 11 (13) |

| Cytokinin | 163 | 9 (4) | 8 (6) |

| Auxin | 355 | 9 (9) | 31 (12)a |

| Methyl jasmonate | 701 | 31 (18)a | 39 (24) |

| Gibberellic acid | 82 | 2 (2) | 4 (3) |

The list of genes upregulated/downregulated by TCP4:VP16-C was compared with those differentially expressed upon hormone treatments by using Microsoft Access. Significance of the overlap in each case was determined by using χ2 test. Bonferroni correction was applied for stringency. Number in parentheses indicates overlap expected by chance.

p <0.01. A significant overlap between the TCP4-upregulated and hormone-upregulated genes/TCP4-downregulated and hormone-downregulated genes would indicate that TCP4 acts to upregulate the level or signaling of the hormone. On the other hand, overlap in the complementary combinations would indicate an antagonistic relationship between TCP4 activity and the hormone level/response.

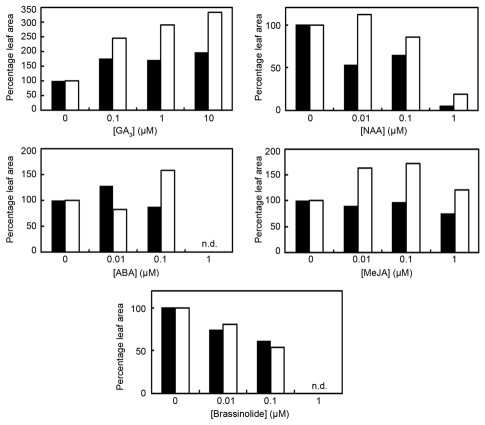

Rescue of Growth Defect in TCP4:VP16-C Leaves by Application of Hormones

Enhanced activity of TCP4 leads to reduced leaf size due to advanced onset of differentiation.4,5 In order to directly determine the relationship between TCP4 activity and hormone function, we measured the growth of TCP4:VP16-C leaves in the presence of exogenously-supplied hormones (Fig. 1). Response to GA3 application was significantly higher in the TCP4:VP16-C leaves compared to wild-type leaves. At 10 µM concentration, GA3 increased leaf size by ∼3.5 times in the transgenic line, compared to ∼2 times increase in wild type. This demonstrated that TCP4 hyper-activation makes leaf cells more sensitive to GA, possibly placing TCP4 downstream to GA-signaling. Similar GA-dependent response was observed in the cotyledons.5 As GA3-treated TCP4:VP16-C cotyledons had larger cells than wild type, it is likely that the partial rescue in leaf growth resulted from enhanced cell expansion. In contrast to GA, the TCP4:VP16-C leaves showed reduced sensitivity to Naphthalene acetic acid (NAA). Unlike the wild-type, the size of TCP4:VP16 leaves remained unchanged. This auxin-resistivity may be due to increased level of the putative negative regulators of auxin response such as SAUR.

Figure 1.

Comparison of hormone-sensitivity of TCP4:VP16-C and Col-0. Graph showing the response of Col-0 (black bar) and TCP4:VP16-C (white bar) to different hormones with regard to leaf growth. Seeds were germinated on MS-agar plates containing increasing concentrations of the following hormones: GA3, NAA, ABA, MeJA and Brassinolide (an active BR) and the area of the first leaf was determined after 21 days (GA3, ABA, NAA) or 17 days (BR, MeJA) for 20 plants. Average area of hormone-treated leaves was expressed as percentage of that of untreated leaves. Error bars are not shown. n.d. denotes not determined.

Although wild type leaves did not respond to ABA, the TCP4:VP16-C leaves grew larger at the highest concentration (0.1 µM) of ABA (>0.1 µM ABA led to loss of seed germination). This suggests that, as in the case of GA, hyper-activity of TCP4 makes leaf cells more responsive to ABA-induced growth. The role of ABA in leaf is restricted to stomatal closure and promotion of senescence. It exerts an inhibitory effect on plant growth under stress, acting antagonistically to other growth stimulators such as GA, IAA and cytokinin. An exception is ABA-deficient mutant aba1, where reduced level of ABA causes stunted growth with smaller leaves,18 suggesting that ABA acts as growth promoter under normal conditions. It is possible that TCP4 acts to suppress ABA level/response, which is rescued by exogenous ABA application.

Though MeJA application did not affect the size of the wild type leaves, it enhanced leaf size in TCP4:VP16-C significantly. This result is surprising since effect of JA in leaf morphogenesis has not been reported. However, external application of MeJA in cultured cells results in G2→M arrest,19 whereas TCP4 blocks G1→S progression, upon expression in yeast,20 indicating that both JA and TCP4 function as cell-division inhibitors. Yet JA application on the TCP4:VP16-C leaves increased leaf size and a set of MeJA-induced genes is downregulated by TCP4 activity. This apparent contradicting result cannot be explained with our current knowledge on TCP function. In case of BR, all plants showed a small but steady decrease in leaf size and there was no difference in the response of wild type and TCP4:VP16-C.

Abbreviations

- GA

gibberellic acid

- BR

brassinosteroid

- ABA

abscisic acid

- MeJA

methyl jasmonate

- NAA

naphthalene acetic acid

- SAUR

small auxin-up RNA

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Nath U, Crawford BC, Carpenter R, Coen E. Genetic control of surface curvature. Science. 2003;299:1404–1407. doi: 10.1126/science.1079354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palatnik JF, Allen E, Wu X, Schommer C, Schwab R, Carrington JC, et al. Control of leaf morphogenesis by microRNAs. Nature. 2003;425:257–263. doi: 10.1038/nature01958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ori N, Cohen AR, Etzioni A, Brand A, Yanai O, Shleizer S, et al. Regulation of LANCEOLATE by miR319 is required for compound-leaf development in tomato. Nat Genet. 2007;39:787–791. doi: 10.1038/ng2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Efroni I, Blum E, Goldshmidt A, Eshed Y. A protracted and dynamic maturation schedule underlies Arabidopsis leaf development. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2293–2306. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.057521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarvepalli K, Nath U. Hyper-activation of the TCP4 transcription factor in Arabidopsis thaliana accelerates multiple aspects of plant maturation. Plant J. 2011;67:595–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olszewski N, Sun TP, Gubler F. Gibberellin signaling: biosynthesis, catabolism and response pathways. Plant Cell. 2002;14:61–80. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Achard P, Gusti A, Cheminant S, Alioua M, Dhondt S, Coppens F, et al. Gibberellin signaling controls cell proliferation rate in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1188–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clouse SD, Sasse JM. BRASSINOSTEROIDS: Essential regulators of plant growth and development. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1998;49:427–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu Y, Bao F, Li J. Promotive effect of brassinosteroids on cell division involves a distinct CycD3-induction pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2000;24:693–701. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lincoln C, Britton JH, Estelle M. Growth and development of the axr1 mutants of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1990;2:1071–1080. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.11.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Werner T, Motyka V, Strnad M, Schmulling T. Regulation of plant growth by cytokinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10487–10492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171304098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeevaart JAD, Creelman RA. Metabolism and physiology of abscisic-acid. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Molec Biol. 1988;39:439–473. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skirycz A, Claeys H, De Bodt S, Oikawa A, Shinoda S, Andriankaja M, et al. Pause-and-stop: the effects of osmotic stress on cell proliferation during early leaf development in arabidopsis and a role for ethylene signaling in cell cycle arrest. Plant Cell. 2011;23:1876–1888. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.084160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nemhauser JL, Hong F, Chory J. Different plant hormones regulate similar processes through largely nonoverlapping transcriptional responses. Cell. 2006;126:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schommer C, Palatnik JF, Aggarwal P, Chetelat A, Cubas P, Farmer EE, et al. Control of jasmonate biosynthesis and senescence by miR319 targets. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kant S, Bi YM, Zhu T, Rothstein SJ. SAUR39, a small auxin-up RNA gene, acts as a negative regulator of auxin synthesis and transport in rice. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:691–701. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.143875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koyama T, Mitsuda N, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Ohme-Takagi M. TCP transcription factors regulate the activities of ASYMMETRIC LEAVES1 and miR164, as well as the auxin response, during differentiation of leaves in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2010;22:3574–3588. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.075598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrero JM, Piqueras P, Gonzalez-Guzman M, Serrano R, Rodriguez PL, Ponce MR, et al. A mutational analysis of the ABA1 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana highlights the involvement of ABA in vegetative development. J Exp Bot. 2005;56:2071–2083. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pauwels L, Morreel K, De Witte E, Lammertyn F, Van Montagu M, Boerjan W, et al. Mapping methyl jasmonate-mediated transcriptional reprogramming of metabolism and cell cycle progression in cultured Arabidopsis cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2008;105:1380–1385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aggarwal P, Padmmanabhan B, Bhat A, Sarvepalli K, Sadhale PP, Nath U. The TCP4 transcription factor of Arabidopsis blocks cell division in yeast at G1→S transition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;410:276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.05.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]