Abstract

Recent reports have demonstrated that Arabidopsis thaliana has the ability to alter its growth differentially when grown in the presence of secretions from other A. thaliana plants that are kin or strangers; however, little knowledge has been gained as to the physiological processes involved in these plant-plant interactions. Therefore, we examined the root transcriptome of A. thaliana plants exposed to stranger vs. kin secretions to determine genes involved in these processes. We conducted a whole transcriptome analysis on root tissues and categorized genes with significant changes in expression. Genes from four categories of interest based on significant changes in expression were identified as ATP/GST transporter, auxin/auxin related, secondary metabolite and pathogen response genes. Multiple genes in each category were tested and results indicated that pathogen response genes were involved in the kin recognition response. Plants were then infected with Pseudomonas syringe pv. Tomato DC3000 to further examine the role of these genes in plants exposed to own, kin and stranger secretions in pathogen resistance. This study concluded that multiple physiological pathways are involved in the kin recognition. The possible implication of this study opens up a new dialog in terms of how plant-plant interactions change under a biotic stress.

Key words: kin recognition, root exudates, transcriptome, Arabidopsis

Introduction

Kin recognition in plants is a phenomenon that has recently gained attention in the ecology and plant biology fields as more evidence for these interactions has accumulated. Dudley and File1 were the first to demonstrate kin recognition in plants through their experiments with Cakile edentula. In their work, C. edentula plants were grown in pots with strangers (plants that were not related) or with kin (plants grown from seed collected from the same mother). Dudley and File1 found that plants grown with strangers allocated significantly more root mass as compared with plants grown with kin, indicating that the C. edentula plants could not only sense the relatedness of their pot neighbors, but also alter their growth according to the relatedness. In another study with Impatiens pallida, it was found that plants grown with strangers increased allocation in stems and leaves vs. when grown in the presence of kin.2 This study established that another plant species has the ability to alter growth in response to the identity of neighbors, although the response differs between species.

Motivated by these studies Biedrzycki et al.3 examined whether similar kin recognition existed in the model species Arabidopsis thaliana as well whether a root derived chemical may be involved in this response. This study differed from the previously mentioned reports in that plants were grown in liquid growth media in tissue culture plates rather than soil and pots and plants were exposed only to the media that contained secretions (secondary metabolite compound released by plant roots into the soil) from another plant (kin or stranger). Interestingly, the results were similar to those of Dudley and File1 in that A. thaliana plants exposed to stranger secretions produced significantly more lateral roots than those exposed to kin secretions.3 Furthermore, addition of sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4), a root secretion inhibitor and known ABC transporter inhibitor, to the media eliminated the increase in root growth between plants exposed to stranger secretions indicating that root secretions are at least partially responsible for kin recognition in A. thaliana.3,4

Supported by evidence that kin recognition occurs in several plant species, including A. thaliana and that root secretion plays a role in this process, Biedrzycki et al.5 elucidated involvement of several root secretion genes involved in the kin recognition process. As previously mentioned, it was determined that addition of sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4), a root secretion and ABC transporter inhibitor, eliminated the increase in lateral root growth associated with exposure to stranger secretions. Therefore, Biedrzycki et al.5 tested four additional ABC transporter inhibitors and found a consistent response in elimination of increased lateral root growth in plants exposed to stranger secretions, further indicating the role of ABC transporters in secretion of the kin recognition signals. Subsequent experiments examining gene expression levels of three ABC transporter genes in plants exposed to own, kin and stranger secretions as well as testing of T-DNA insertion mutants of these genes supported the involvement of ABC transporter in varying levels in kin recognition interactions.

Although the above mentioned studies shed light on a portion of the mechanics of the kin recognition process, it is highly unlikely that only ABC transporter genes are involved in the interaction; it is possible that genes involved in growth as well as signaling and other process would be associated with the response as we see changes in root growth patterns in response to kin and stranger secretions. Therefore, this study examined the transcriptome of root tissues of A. thaliana plants exposed to kin or stranger secretions in order to elucidate additional genes or pathways that may be involved in this mysterious plant behavior.

Upon analysis of the root transcriptome, four categories of genes were identified as having significant gene expression changes in A. thaliana plants exposed to stranger secretions vs. those exposed to kin secretions (see Results). These categories were ATP Binding Cassette/Glutathione S-Transferase transporter genes, secondary metabolite genes, auxin/auxin related genes and most interestingly pathogen response genes. This led us to the question: why would A. thaliana plants increase their expression of pathogen response genes when grown in the presence of stranger secretions?

One possible reason may be that the plants sense the stranger secretions as some sort of a biotic stress and have acquired a type of evolutionary trade-off mechanism. Plants have adapted mechanisms to deal with multiple types of biotic stresses such as competition and disease and herbivore resistance; however, these mechanisms come at a cost to the plant. Production of secondary metabolites diverts energy for growth and reproduction. Often, plants are exposed to multiple stresses simultaneously and many studies have looked at how plants deal with these double threats in terms of allocation of resources. The defense-stress cost (DSC) hypothesis proposes that the costs of defense increase and are magnified under competitive stress from other plants as resources decline.6–9 This hypothesis has proven true in several situations,10–14 however it has been argued that proving this hypothesis may be dependent upon the species of target plant, species of competitor and nature of stress (herbivore or pathogen). One study that does support the DSC hypothesis examined the cost of induced responses (IR) in A. thaliana under competition stress.15 Induction of wound related chemical defenses when plants were grown in the presence of other Arabidopsis plants decreased total seed production by 15% overall. Alternatively, competition reduced peroxidase activity suggesting decreased systemic acquired resistance; however, trypsin inhibitor levels (indicative of IR) were not altered. Therefore, competition caused a decrease in overall systemic defense and a reduction of seed production but did not cause a change in induced defense responses.16

Although much of the data look at the cost dual stress and competition studies is conflicting, Broz et al.17 have shown that when Centaurea maculosa plants were treated with the defense signaling molecule, methyl jasmonate, plants grown with heterospecific neighbors (Festuca idahoensis) allocated more resources toward growth than when grown with conspecific (C. maculosa) plants where they increased total levels of phenolics produced. Since high conspecific density in the field may increase herbivore attack rates, it may increase survival to produce more phenolics, whereas in the presence of a heterospecific stand, primary growth would increase competition and perhaps survival.17 This study highlights most importantly, that C. maculosa plants can recognize surrounding plants and alter their survival strategy accordingly when under a stress simulation.

Therefore, based on the preliminary results from our transcriptome analysis, we further investigated whether A. thaliana plants exposed to stranger secretions are less susceptible to pathogen infection than those exposed to kin secretions despite the perceived increase in stress due to increased competition under the stranger regime.3

Results

Transcriptome analysis.

We investigated whether there was a difference in gene expression between plants grown with kin secretions vs. those grown with stranger secretions. Since our previous data suggested that roots respond to a kin recognition cue by increased foraging demonstrated by increased lateral root growth, we choose the root as a marker organ for gene expression analysis. We hypothesized that any change at the transcript level in plant roots exposed to kin and stranger secretions might be interpreted as a genetic marker for recognition. Whole-genome microarray analyses were performed on one accession (CHA) exhibiting strong differential growth from our published studies in reference 3. We compared gene expression between CHA seedlings growing in vitro supplemented with kin (CHA) or stranger (ecotype Col-0) secretions.

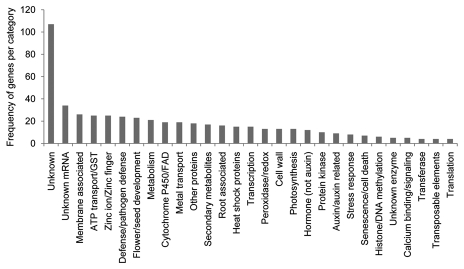

Genes representing a significant fold change of at least ±1.5 between stranger vs. kin secretion exposed roots were classified into 29 categories representing a variety of plant processes (Fig. 1). Unfortunately, genes with unknown functions had the highest frequency. However, membrane associated genes and ATP/GST transporter genes were the next highly represented categories, further implying the role of ABC transporters in kin recognition. Several other categories indicated a high number of changes in gene expression levels when comparing plants exposed to stranger secretions vs. those exposed to kin secretions including unknown mRNA, zinc ion/zinc finger, flower/seed development, metabolism, metal transport, unidentified proteins and secondary metabolites. Unexpectedly, pathogen response and defense genes are highly represented among genes with significant expression changes in stranger vs. kin exposure (Fig. 1). The abundance of gene categories represented indicates that kin recognition involves a multitude of physiological processes.

Figure 1.

Frequency of genes per category with significant changes in expression in stranger vs. kin exposed roots. Roots of six plants were pooled for each of the kin (CHA plants exposed to CHA secretions) and stranger (CHA plants exposed to Col-0) treatments. Fold changes were considered significant comparing stranger vs. kin at ±1.5-fold expression levels.

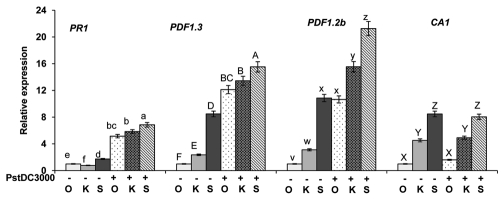

Additional analysis of 20 genes with the highest fold change in gene expression in stranger vs. kin exposed roots illustrated that pathogen response genes are highly represented in this interaction (Fig. 2). Based on qualitative analysis of data gathered from the categories and frequency of genes with altered expression (Fig. 1) and the genes exhibiting the highest fold change (Fig. 2) we chose to continue to investigate and revalidate the role of four pathogen response genes in kin recognition in addition to 4 genes in categories of auxin/auxin related genes, four secondary metabolite genes and 5 ATP/GST transporter genes.

Figure 2.

Percentage of genes per category among the 20 genes with the highest fold changes in expression in stranger vs. kin exposed roots. Roots of six plants were pooled for each of the kin (CHA plants exposed to CHA secretions) and stranger (CHA plants exposed to Col-0) treatments. Fold changes comparing gene expression in stranger vs. kin for this figure ranged from ±3.3–6.7.

Revalidation of the genes of interest resulted in an overall validation rate of 64.47% (Table 2). Pathogen response genes PDF1.3, PDF1.2b and CA1 were validated for increased expression in plants exposed to stranger vs. kin secretions (Table 2). All five of the ATP/GST transporter genes were validated for decreased expression in the stranger exposed plants. One auxin responsive gene, Auxin Related Family Protein, was validated for increased expression indicating that increased plant growth may be an important function during the kin recognition process, therefore, it is possible that this gene plays a role in the enhanced lateral root growth seen in plants exposed to stranger secretions.3 Two secondary metabolite genes were also revalidated for their expression, although one increased in expression (MLP-related), while the other was decreased in expression (UGT73C6) in plants exposed to stranger vs. kin secretions leaving the role of secondary metabolites in kin recognition physiology less clear.

Table 2.

Microarray and RT-PCR fold-changes between plants exposed to stranger vs. kin secretions for 17 selected genes

| S. No | Gene | Description | Microarray | RT-PCR |

| 1 | AT2G26010.1 | PDF1.3 | 4.39 | 3.420027 |

| 2 | AT2G26020.1 | PDF1.2b | 4.01 | 3.179126 |

| 3 | AT3G01500.3 | CA1 | 2.05 | 5.254996 |

| 4 | AT1G34047.1 | Encodes a defensin-like (DEFL) family protein | 4.76 | −5.84942 |

| 5 | AT4G05380.1 | AAA-type ATPase family protein | −1.28 | −3.29006 |

| 6 | AT2G04050.1 | MATE efflux family protein | −1.93 | −3.06706 |

| 7 | AT1G21120.1 | O-methyltransferase, putative | −1.81 | −3.58282 |

| 8 | AT1G15520.1 | ATPDR12/PDR12 (PLEIOTROPIC DRUG RESISTANCE 12); ATPase, coupled to transmembrane movement of substances | −2.96 | −3.25259 |

| 9 | AT1G71330.1 | ATNAP5 (Arabidopsis thaliana non-intrinsic ABC protein 5) | −3.13 | −1.59911 |

| 10 | AT5G58310.1 | hydrolase, α/β fold family protein | 2.63 | −2.34853 |

| 11 | AT1G80390.1 | IAA15 (indoleacetic acid-induced protein 15); transcription factor | 6.72 | −1.23876 |

| 12 | AT4G34770.1 | auxin-responsive family protein | 1.68 | 3.659894 |

| 13 | AT5G20820.1 | auxin-responsive protein-related | 1.73 | −1.84829 |

| 14 | AT2G36790.1 | UGT73C6 (UDP-GLUCOSYL TRANSFERASE 73C6); UDP-glucosyltransferase/UDP-glycosyltransferase/transferase, transferring glycosyl groups | −1.85 | −2.80119 |

| 15 | AT1G61120.1 | terpene synthase/cyclase family protein | −2.04 | 5.244124 |

| 16 | AT5G54060.1 | UF3GT (UDP-GLUCOSE:FLAVONOID 3-O-GLUCOSYLTRANSFERASE); transferase, transferring glycosyl groups | −2.19 | 0.25713 |

| 17 | AT1G14960.1 | major latex protein-related/MLP-related | 3.81 | 1.389436 |

| Validation average | 64.47% | |||

Highlighted microarray and RT-PCR fold-changes represent genes with opposite gene expression direction (more/less expressed than the reference).

Pathogen infection.

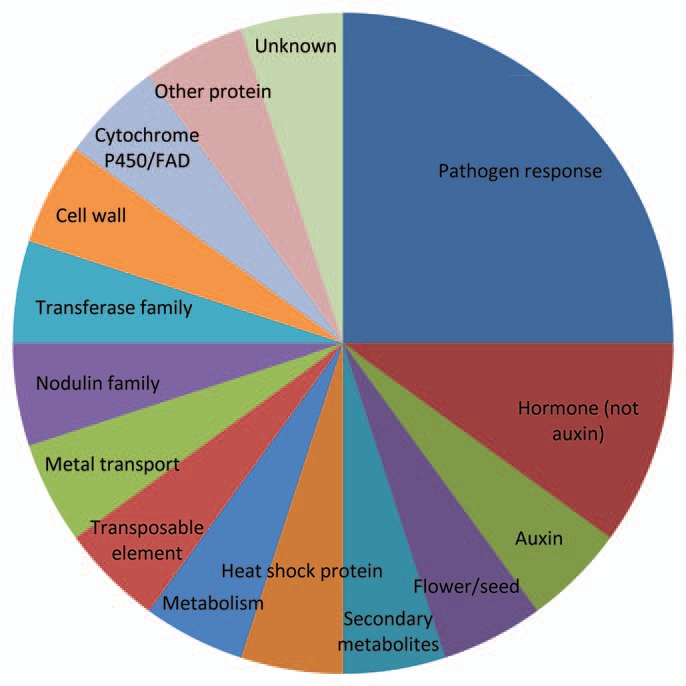

Based on the revalidated increased gene expression in pathogen response genes PDF1.3, PDF1.2b and CA1 plants exposed to stranger secretions vs. kin secretions, identified in the transcriptome analysis, we endeavored to determine whether plants were less susceptible to pathogen attack when they are exposed to stranger secretions vs. own or kin secretions. Here plants were grown in multi-well tissue culture plates for seven days where the plants were exposed to the appropriate secretions in liquid growth media as described in Biedrzycki et al.3 On the eighth day, plants were “leaf-dip” infected with P. syringae PstDC3000::GFP and placed back into their appropriate wells. The 3 identified pathogen response genes PDF1.3, PDF1.2b and CA1 as well as pathogenesis related PR1 gene expression levels were investigated in A. thaliana plants 24 h post-infection with P. syringae. All four of these genes exhibited statistically significant increases in gene expression in plants exposed to stranger vs. kin secretions in control as well as infected plants (Fig. 3) (PR1 1.74, PDF1.3 12.25, PDF1.2b 10.86-fold higher compared with plants exposed to kin secretions). Additionally, PDF1.3, PDF1.2b and PR1 gene expression was increased in infected plants as compared with control plants, with plants exposed to stranger secretions exhibiting statistically higher expression than plants exposed to own or kin secretions (PR1 6.86, PDF1.3 15.5, PDF1.2b 25.25) (Fig. 3). This result of finding higher expression of a pathogen response gene in the plants exposed to stranger secretions is interesting, as this indicates that plants exposed to stranger secretions are not only using more energy for root-allocation but also exerting more energy on defense costs even in absence of a pathogen.3

Figure 3.

Expression analyses of key SA and JA/ET related pathway genes. The 14-d-old seedlings exposed to secretions own, kin and stranger were co-cultured with PstDC3000 (OD600 = 0.1). After 24 h of post infection RNA was isolated from roots and RT-PCR was performed as described in Materials and methods. Expression levels are represented in arbitrary units, taking the value for uninfected own plants as equivalent to 1. Data shown as the mean ± SD of the two replicates and bars with same letters indicate no significant difference between means as determined by ANOVA-protected DMRT (p = 0.05).

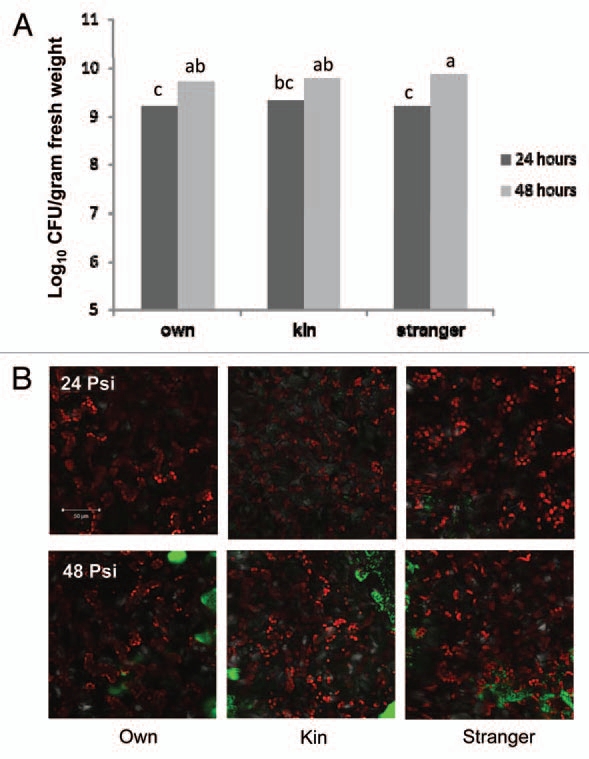

Further, of the 20 genes with the highest fold change in expression between plants exposed to stranger vs. kin secretions, 25% were defense related genes, supporting our current data, indicating defense related genes are involved with the kin/stranger recognition response and perhaps plants exposed to stranger secretions would be less susceptible to pathogen attack as key pathogen defense genes are already being expressed. Therefore, we conducted infection assays to determine if the increase in expression of disease resistance genes translated to increased resistance in planta. Additionally, infection intensity was examined in A. thaliana plants exposed to own, kin and stranger secretions at 24 and 48 h post-infection. Although infection in plants exposed to own, kin and stranger secretions increased between 24 and 48 h within the treatment, there was no significant difference between infection levels of plants exposed to own, kin or stranger secretions based on CFU and confocal microscopy data (Fig. 4). This data suggests that the increase in pathogen response gene expression does not translate into a functional quantitative increase in pathogen resistance in plants exposed to stranger secretions.

Figure 4.

Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (PstDC3000) infection of A. thaliana (CHA) plants exposed to own, kin or stranger secretions at 24 and 48 h post-inoculation (psi). (A) Plants were exposed to their own, kin or stranger root secretions for 7 d then infected with PstDC3000::GFP. CFUs of the whole plant were taken at 24 and 48 h post-infection. Each CFU experiment was repeated twice with ten replications. The data were subjected to one-way ANOVA and mean separations were performed by Duncan's multiple range test for segregating means where the level of significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. (B) Images were captured to visualize PstDC3000::GFP infection in the apoplastic leaf tissues in A. thaliana (CHA) plants by confocal scanning laser microscopy, Z-stack sections (approximately 20 µM thick).

Discussion

Recent studies have shown that a few plant species such as Cakile edentula, Impatiens pallida and Arabidopsis thaliana have the ability to recognize surrounding plants specifically as related (kin) vs. non-related (stranger) plants of the same species and alter their growth accordingly.1–3,5 Demonstration of these species' ability to recognize surrounding plants as related vs. nonrelated posed the question, how do plants recognize kin? A study conducted by Biedrzycki et al.3 found that A. thaliana plants exposed to the media which previously contained kin plants grew less lateral roots than plants exposed to the media from stranger plants, indicating that A. thaliana plants can sense and respond to a chemical cue left in the media. A. thaliana plants are known to secrete a myriad of compounds, and when a known root secretion inhibitor sodium orthovanadate was employed in the same experimental setup, there was no longer significant difference in A. thaliana root growth when plants were exposed to media from kin or strangers.4 Therefore, root secretions were determined to be at least partially involved in the kin recognition process in A. thaliana.

The next logical question in this series of investigations is what other processes are involved in the kin and stranger recognition phenomena? In order to answer this question, we examined the root transcriptome of plants exposed to stranger secretions vs. plants exposed to kin secretions and determined that a myriad of physiological processes are involved in the kin recognition response (Fig. 1) based on changes in gene expression levels. Through analysis, genes in four categories of interest were chosen for revalidation, ATP/GST transporters, auxin/auxin related genes, secondary metabolites and pathogen response genes. The data for secondary metabolite and auxin related genes did not show any clear trends as far as universal involvement for these genes. The genes in the ATP/GST transporter category all exhibited downregulation under conditions where the plants were exposed to stranger secretions vs. kin secretions. Although previous reports have indicated that ABC transporter genes are involved in kin recognition, these results are not surprising as ABC transporters can show specificity for certain compounds.3,18 Therefore, it is possible that the compounds involved in recognition of stranger plants do not have specificity for the ATP/GST transporters identified here, therefore resulting in the downregulation of genes. The most curious discovery that came from investigation of the root transcriptome of plants exposed to stranger vs. kin secretions was increased expression in a number of pathogen response genes. Revalidation confirmed this increase in three genes, PDF1.3, PDF1.2b and CA1.

Results from the transcriptome analysis showing an increase in pathogen response gene expression inspired our final question, why do plants recognize kin? Although these previous studies have identified changes in growth patterns that may suggest decreased competition in the presence of kin, they do not confirm any survival benefit to the plant as a result of this recognition. Perhaps the ability to distinguish kin vs. stranger plants and to be more competitive also confers an evolutionary benefit such as enhanced pathogen resistance?

As previously mentioned, the DSC hypothesis proposes that the costs of defense increase and are magnified under competitive stress from other plants as resources decline, which would lead us to believe that in our system, the plants assumed to be under more stress, those exposed to stranger secretions, would have less resources available for defense as they have invested more into competition by producing more lateral roots.3,6–9 In order to determine whether plants were more susceptible to pathogen attack when they are exposed to stranger secretions vs. own or kin secretions we grew plants as described in Biedrzycki et al.3 Here plants are grown in multi-well tissue culture plates for seven days where the plants were exposed to the appropriate secretions in liquid growth media. On the eighth day, plants were “leaf-dip” infected with PstDC3000::GFP and placed back into their appropriate wells. Tissue was collected from control and uninfected plants at 24 h post-inoculation for RNA expression studies and CFUs and confocal images of bacterial infection were taken at 24 and 48 h post-inoculation. We chose a well-known disease resistance gene PR1 as well as the genes identified through the microarray (PDF1.3, PDF1.2b and CA1) to examine whether there were differences in expression levels between plants exposed to their own, kin or stranger secretions with and without bacterial infection. PR1 (pathogenesis-related) is known to be salicylic acid dependent and CA1 also known as salicylic acid binding protein 3 (SAPB3) is assumed to be involved in plant defense based upon the known function of its ortholog in tobacco.19 PDF1.3 and PDF1.2b (plant-defensins) are ethylene and jasmonate sensitive; however they known to be repressed by salicylic acid at high concentrations as these two pathways (SA/JA) are often antagonistic.20,21

In uninfected plants, we found plants exposed to stranger secretions vs. own or kin secretions had significantly higher expression of PR1, PDF1.3, PDF1.2b and CA1 (Fig. 3). This result of finding higher expression of a pathogen response gene in the plants exposed to stranger secretions supported the results of our transcriptome analysis, as this indicates that plants exposed to stranger secretions are not only using more energy for root-allocation but also exerting more energy on defense costs even in absence of a pathogen.3 Therefore, we conducted infection assays to determine if the increase in expression of disease resistance genes translated to increased resistance in planta.

Interestingly, our CFU data and infection images show no significant difference between own, kin or stranger root secretion treatments in terms of bacterial infection at 24 or 48 h postinoculation (Fig. 4A and B). Additionally, when plants were infected with PstDC3000::GFP, we found that expression levels for PR1, PDF1.3, PDF1.2b and CA1 remained higher in the plants exposed to stranger secretions as compared with plants exposed to own or kin secretions. As previously mentioned, PR1 is induced by salicylic acid (SA) whereas PDF1.3 and PDF1.2b are induced by ethylene and jasmonic acid (JA). The SA and JA pathways are known to be an antagonistic, when SA is at low concentrations, the pathways can work synergistically, however higher concentrations of SA are known to trigger repressions of JA sensitive PDF1.3 and PDF1.2b, therefore it is not surprising that we see increases in expression of PR1 and PDF1.3 and PDF1.2b as concentrations of SA may not be high enough to inhibit the defensins.20–22

Most puzzling is that as previously mentioned, we found that expression levels for PR1, PDF1.3, PDF1.2b and CA1 remained higher in the plants exposed to stranger secretions as compared with plants exposed to own or kin secretions when all three treatments were infected, but our CFU data and infection images show no significant difference between own, kin or stranger root secretion treatments in terms of bacterial infection at 24 or 48 h post-inoculation (Fig. 4A and B). It is possible that even though this is a statistically significant increase in gene expression, that it is not a biologically relevant increase to confer additional pathogen resistance. Alternatively, studies investigating the roles of oxylipins in plants have demonstrated that 9-hydroxoctadecatrienoic acid (9-HOT) insensitive mutants, noxy2, are defective in both lateral root development and plant defense therefore indicating that these two plant activities have common pathways or signaling molecules.23 Therefore, one could speculate that the A. thaliana plants exposed to stranger secretions are somehow compartmentalizing some of what appears to be their pathogen defense, but it may actually be a side effect of their competition response for root growth. Furthermore, plant defensins have been shown to be involved in mediating abiotic stress such as salinity and metal hyperaccumulation. Perhaps the increase in defensin expression is a result of the perceived stress conditions due to increased competition between the plants exposed to stranger secretions.24

One other possible scenario is that there is a compound present in the secretions when plants are exposed to stranger secretions, not found in own or kin secretions, that induces production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the exposed plants, which is known to induce defense related genes.28 Prithiviraj et al. (2006)25 reported that even low doses of (±) catechin, an allelochemical found in the root secretions of Centaurea stoebe (spotted knap-weed) triggered ROS in treated plants which lead to upregulation of PR1. Additionally, plants treated with (±) catechin exhibited increased growth, assumed to be a secondary effect due to cell wall loosening, again linking these two processes of growth and defense.25

Although the data presented did not support our original hypothesis, the results that A. thaliana plants exposed to stranger secretions exhibit higher PR1, PDF1.3, PDF1.2b and CA1 expression with or without pathogen infection and that this increase in gene expression confers no additional pathogen resistance as compared with plants exposed to own or kin secretions opens a new chapter in understanding plant kin and stranger recognition processes. A recent study by Masclaux et al.26 that examined the transcriptome of A. thaliana plants found no discernable differences in gene expression between plants grown in the presence of kin or non-kin. This study differed from ours in that we grew our plants in liquid culture, perhaps better facilitating the exchange of root secretions and we looked specifically at the root tissues of plants grown in the presence of kin or strangers. Therefore, it is not surprising that the results from our study differed from those of Masclaux et al.26 and that we identified 29 gene categories in which there were changes in gene expression between plants exposed to stranger vs. kin secretions. In the future, information gleaned from the transcriptome analysis may aid in identification of other genes and their roles in these plant-plant interactions. Further investigations to elucidate the intricacies of plant growth, development and response and how these all interact in the context of kin and stranger recognition will be necessary in the coming years for this budding field of plant biology.

Methods and Materials

Root secretion exposure.

Methods were repeated from Biedrzycki et al.3 The experiments used a natural ecotype, CHA25 (collected by Dr. K. Donohue, Duke University), as the target accession and Col-0 seeds procured from Lehle seeds, Texas, as the stranger accession. Seeds were surface sterilized with 50% sodium hypochlorite for 3 min then washed twice with sterile ddH2O. Seeds were stored for one week in a refrigerator to ensure germination. Seeds were sown in low density, approximately 80–100 seeds of a single accession, evenly spaced on Murashige and Skoog (1964)27 media (3% sucrose) plates (100 × 15 mm) for seven days. On the seventh day, under sterile conditions, seedlings were added individually to wells of a 24 well tissue culture plate (85.5 mm × 127.5 mm, BD Falcon NY, USA) with 1 mL of MS liquid media per seedling (1% sucrose). Plates were placed on a rotary shaker (90 rpm) under cool white fluorescent light (45 mmol m−2 sec−1) at 25 ± 2°C. Order of plates on the shaker was re-randomized daily. Each day for seven days target CHA plants in the own treatment were lifted out of their wells gently with forceps and placed back into the well containing their exudates. Target CHA plants in the kin treatment were lifted from their wells gently and placed into a well with media that previously contained a sibling. Target CHA plants in the strangers treatment were lifted out of their wells gently and placed in a well with media that previously contained a stranger plant (Col-0 ecotype) (see Biedrzycki et al.)3 All seedlings were maintained under sterile conditions. Seven days after transfer to liquid media, seedlings were removed from the wells.

RNA isolation.

Total RNA was extracted from roots A. thaliana ecotype CHA plants exposed to own, kin or stranger secretions. Roots from six plants were pooled from each treatment for RNA extraction. RNA was extracted using PureLink RNA isolation buffer according to the manufacturer's instruction manual (Invitrogen, CA USA). Possible contaminant genomic DNA in RNA extract was removed using Turbo DNAfree™ kit (Ambion). The concentration of total RNA was determined spectrophotometrically at 260 nm. The integrity of RNA was checked by electrophoresis in formaldehyde denaturing gels stained with ethidium bromide. For microarray analysis, total RNA was sent to Beckman Coulter Genomics.

Microarray.

Microarray was performed as follows by Beckman-Coulter Genomics, NC.

RNA extraction and assessment at beckman-coulter genomics.

The quantity of each of the total RNA samples associated with this project was determined by spectrophotometry and the size distribution was assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer.

Gene expression profiling at beckman-coulter genomics.

Five hundred nanograms of total RNA was converted into labeled cRNA with nucleotides coupled to fluorescent dye Cy3 using the Quick Amp Kit (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol. The A260/280 ratio and yield of each of the cRNAs was verified (data not shown).

Cy3-labeled cRNA (1.65 µg) from each sample was hybridized to an Agilent Arabidopsis Version 4 Microarray. The hybridized array was then washed and scanned and data was extracted from the scanned image using Feature Extraction version 10.2 (Agilent Technologies).

Gene classification.

Genes exhibiting significant changes in expression as determined by analysis by Beckman-Coulter Genomics in stranger vs. kin comparisons were identified and grouped into functional, structural or locational classifications based on information available from ABRC (www.arabidopsis.org). The classification of genes with at least (±)1.5 fold change in expression into categories aided in identifying groups of genes that may have the most promising activity in the kin response. Genes of interest were those represented as significant in stranger vs. kin with either an inverse response in kin vs. own or not represented in kin vs. own transcriptome comparisons. Further, the 20 genes with the largest (±) fold change in expression were identified. Assessment of the frequency of genes in a represented in a given gene category for increased or decreased gene expression in stranger vs. kin exposed plants as well as the data regarding the genes which had the highest (±) fold change guided qualitative-based decisions to choose genes for revalidation.

Revalidation of genes of interest.

Seventeen genes were selected for revalidation by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (Table 1). Total RNA was isolated as described above. Total RNA used for RT-PCR verification was obtained from plants that were grown independently from those used to isolate RNA for microarray analysis. First-strand cDNAs were synthesized from 500 ng of total RNA in 20 µl final volume, using M-MuLV reverse transcriptase and oligo-dT (18-mer) primer (Fermentas GmbH, Germany). PCR amplifications were performed using PCR mixture (15 µl) that contained 1 µl of RT reaction product as template, 1x PCR buffer, 200 µM dNTPs (Fermentas GmbH), 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega), and 0.1 µM of each primer depending on the gene. PCR was performed at initial denaturation at 94°C for 4 min, 22 or 26 cycles (30 sec at 94°C; 30 sec at 60°C; 30 sec at 94°C), and final elongation (8 min at 72°C) using a thermal cycler (Bio-rad). The PCR products were separated on 1.4% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide (0.001%), and documented in a gel documentation system and the bands were quantified using E.A.S.Y. WIN 32. Each band was normalized against the intensity obtained with the same cDNA using the UBQ1 primers.

Table 1.

Details of the primers used in the semi-quantitative RT-PCR for validation of microarray data

| S. No. | Gene | Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Amplicon size (bp) |

| 1 | AT2G26010.1 | FP | AGT TGT GCG AGA AGC CAA GT | 194 |

| RP | CAC ACC ATG AAG CAC CAA GT | |||

| 2 | AT2G26020.1 | FP | CAT GGC TAA GTT TGC TTC CA | 154 |

| RP | CTT GCA TGC ATT GCT GTT TC | |||

| 3 | AT3G01500.3 | FP | AAC CAA CCC TGC TTT GTA CG | 181 |

| RP | GCC ACC GTA TTT GAC CTT GT | |||

| 4 | AT1G34047.1 | FP | CGT TCC CAG GTA CAA ATG CT | 160 |

| RP | CGG AAT GGA AGC AAA GGT TA | |||

| 5 | AT4G05380.1 | FP | CTG AGA CCA GGA AGG ATG GA | 190 |

| RP | CCG GAT CCT TGC TTA CCA TA | |||

| 6 | AT2G04050.1 | FP | GAG CAC CTT GTC CCC TGT AA | 194 |

| RP | GTG AAG GAG GTT GCA AGA GC | |||

| 7 | AT1G21120.1 | FP | CGT GGT GCT AGA AGG AGG AG | 166 |

| RP | CAC ACC TTT GAA GCC TTG GT | |||

| 8 | AT1G15520.1 | FP | ATT TGC GAT GCT CGT CTT CT | 177 |

| RP | GTT TCG CTC GAG TTT TCG AC | |||

| 9 | AT1G71330.1 | FP | AAG AGA GGG CGA AAG GTA GC | 184 |

| RP | TTC ACA GGA GCT TGC ACA TC | |||

| 10 | AT5G58310.1 | FP | GAC AGG CAA GGA CCA TTT GT | 150 |

| RP | GCT GCT TGA AGG AGG AAT TG | |||

| 11 | AT1G80390.1 | FP | TAA AAC TCG GGG AAG CAC AC | 114 |

| RP | CGT ATT TCC GCC TCA CTG TT | |||

| 12 | AT4G34770.1 | FP | ATC GGA CTC TCT CAG GCA AA | 117 |

| RP | CAC ATA GAC GGC CAC ATG AC | |||

| 13 | AT5G20820.1 | FP | GGA GGA CAT ACC ACG TGA GC | 140 |

| RP | CCA AAG CAA ATG CTC AAA CA | |||

| 14 | AT2G36790.1 | FP | CTT CAA GGA GGC AAG GTC TG | 170 |

| RP | CAA GGC AAA CGT AGA GCA CA | |||

| 15 | AT1G61120.1 | FP | TGG CTA CGT GAA GCT GAA TG | 164 |

| RP | TCG TAA TTT CCC GGT TTG AG | |||

| 16 | AT5G54060.1 | FP | CCA TTG GAT ACC GGA AAT TG | 133 |

| RP | TGA CAT TTC CTT GCC ATC AA | |||

| 17 | AT1G14960.1 | FP | GAG AAT ATG GCG GTG ACG AT | 149 |

| RP | GAG TCT TCG GTG CGT TTC TC | |||

| 18 | NM_127025 | FP | AGG TGC TCT TGT TCT TCC CTC GAA | 150 |

| RP | TAC ACC TCA CTT TGG CAC ATC CGA |

Infection of plants.

Plants were grown as in “secretion exposure” method above. Additional methods were modified from Melotto et al.28 Pseudomonas syringae pv. Tomato DC3000 (PstDC3000::GFP) was obtained from Gwyn Beattie, Department of Plant Pathology, Iowa State University. Overnight liquid cultures were isolated from single colonies of PstDC3000::GFP from LB containing 50 µg/ml rifampicin and kanamycin. Overnight cultures were grown at 30°C in LB liquid also containing 50 µg/ml rifampicin and kanamycin and kept on a shaker set at 190 rpm. Bacteria were then isolated by centrifugation and re-suspended in sterile ddH2O to the final concentration 0.1 OD600 containing 0.05% Silwet L-77.

A. thaliana leaves were then dipped into a microcentrifuge tube containing the bacterial suspension and the suspension was refreshed after every 8 plants. Plants were then placed back into their respective wells in the 24 well tissue culture plates.

Colony forming units were then determined at 24 and 48 h post-inoculation. Whole plants were removed from their wells, blotted and fresh weight was determined. Plants were then placed in microcentrifuge tubes with sterile ddH2O and the plant tissue was homogenized. Liquid from the tube was serially diluted and plated onto LB plates containing 50 µg/ml rifampicin and placed in a 30°C incubator overnight. Colonies were then counted and recorded.

Microscopy.

To view PstDC3000::GFP cells in the apoplastic leaf tissues by confocal scanning laser microscopy, Z-stack sections (approximately 20 µM thick) were imaged with a Zeiss 40x-W-Apochromat objective lens using a Zeiss LSM 510VIS point standing confocal microscope. The 488-nm laser line of the argon laser was used for excitation and emission. Images were acquired 24 and 48 h post-inoculation.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

Total RNA was isolated as described above after 24 h of infection. Analyses PR1, PDF1.3, PDF1.2b and CA1 gene expressions were performed by using RT-PCR as described above. The UBQ1 gene was amplified and used as a quantitative control.

Experimental design and data analysis.

Each CFU experiment was repeated twice with ten replications. All the observations and calculations were made separately for each set of experiments and were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The data were subjected to one-way ANOVA and mean separations were performed by Duncan's multiple range test for segregating means where the level of significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.29

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs. Kirk Czymmek and Amutha Sampath Kumar for their technical advice and assistance.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Dudley SA, File AL. Kin recognition in an annual plant. Biol Lett. 2007;3:435–438. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy GP, Dudley SA. Kin recognition: competition and cooperation in Impatiens (Balsaminaceae) Am J Bot. 2009;96:1990–1996. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0900006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biedrzycki ML, Jilany TA, Dudley SA, Bais HP. Root exudates mediate kin recognition in plants. Commun Integral Biol. 2010;1:28–35. doi: 10.4161/cib.3.1.10118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loyola-Vargas VM, Broeckling CD, Badri D, Vivanco JM. Effect of transporters on the secretion of phytochemicals by the roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2007;225:301–310. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0349-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biedrzycki ML, Venkatachalam L, Bais HP. The role of ABC transporters in kin recognition in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal Behav. 2011:6. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.8.15907. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKey D. Adaptive patterns in alkaloid physiology. Am Nat. 1974;108:305–320. doi: 10.1086/282909. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zangerl AR, Bazzaz FA. Theory and pattern in plant defense allocation. In: Fritz S, Simms EL, editors. Plant resistance to pathogens and herbivores: ecology, evolution and genetics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1992. pp. 363–390. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton JG, Zangerl AR, DeLucia EH, Berenbaum MR. The carbon-nutrient balance hypothesis: its rise and fall. Ecol Lett. 2001;4:86–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2001.00192.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siemens DH, Lischke H, Maggiulli N, Schürch S, Roy BA. Cost of resistance and tolerance under competition: the defense-stress benefit hypothesis. Evol Ecol. 2003;17:247–263. doi: 10.1023/A:1025517229934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reboud X. Till-Bottraud. The cost of herbicide resistance measured by a competition experiment. Theo Appl Gen. 1991;82:690–696. doi: 10.1007/BF00227312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergelson J. The effects of genotype and the environment on costs of resistance in lettuce. Am Nat. 1994;143:349–359. doi: 10.1086/285607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams MM, Jordan N, Yerkes C. The fitness cost of resistance in Jimsonweed (Datura stramonium L.) Am Midl Nat. 1995;133:131–137. doi: 10.2307/2426354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Purrington CB, Bergelson J. Fitness consequences of genetically engineered herbicide and antibiotic resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 1997;145:807–814. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.3.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldwin IT, Hamilton W. Jasmonate-induced responses of Nicotiana sylvestris results in fitness costs due to impaired competitive ability for nitrogen. J Chem Ecol. 2000;26:915–952. doi: 10.1023/A:1005408208826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stotz HU, Kroymann J, Mitchell-Olds T. Plant-insect interactions. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1999;2:268–272. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(99)80048-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cipollini DF. Does competition magnify the fitness costs of induced responses in Arabidopsis thaliana? A manipulative approach. Oecologia. 2002;131:514–520. doi: 10.1007/s00442-002-0909-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broz AK, Broeckling CD, De-la-Peña C, Lewis MR, Greene E, Callaway RM, et al. Plant neighbor identity influences plant biochemistry and physiology related to plant defense. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:115–129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Badri DV, Loyola-Vargas VM, Broeckling CD, De-la-Peña C, Jasinski M, Santelia D, et al. Altered profile of secondary metabolites in the root exudates of Arabidopsis ATP-binding cassette transporter mutants. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:762–771. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.109587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slaymaker DH, Navarre DA, Clark D, del Pozo O, Martin GB, Klessig DF. The tobacco salicylic acid-binding protein 3 (SABP3) is the chloroplast carbonic anhydrase, which exhibits antioxidant activity and plays a role in the hypersensitive defense response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11640–11645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182427699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laurie-Berry N, Vinita J, Street IH, Kunkel BN. The Arabidopsis thaliana JASMONATE INSENSITIVE 1 gene is required for suppression of salicylic acid-dependent defenses during infection by Pseudomonas syringae. Mol Plant Microb Inter. 2006;7:789–800. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loake G, Grant M. Salicylic acid in plant defence—the players and protagonists. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10:466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ndamukong I, Abdallat AA, Thurow C, Fode B, Zander M, Weigel R, et al. SA-inducible Arabidopsis glutaredoxin interacts with TGA factors and suppresses JA-responsive PDF1.2 transcription. Plant J. 2007;50:128–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vellosillo T, Martinez M, Lopez MA, Vicente J, Cascon T, Dolan L, et al. Oxylipins produced by the 9-lippoxygenase pathway in Arabidopsis regulate lateral root development and defense responses through a specific signaling cascade. Plant Cell. 2007;19:831–846. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.046052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirouze M, Sels J, Richard O, Czernic P, Loubet S, Jacquier A, et al. A putative novel role for plant defensins: a defensin from the zinc hyper-accumulating plant, Arabidopsis halleri, confers zinc tolerance. Plant J. 2006;47:329–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prithiviraj B, Perry LG, Badri DV, Vivanco JM. Chemical facilitation and induced pathogen resistance mediated by a root-secreted phytotoxin. New Phytol. 2007;173:852–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masclaux F, Hammond RL, Meunier J, Gouhier-Darimont C, Keller L, Reymond P. Competitive ability not kinship affects growth of Arabidopsis thaliana accessions. New Phytol. 2010;185:322–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Planta. 1962;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melotto M, Underwood W, Koczan J, Nomura K, He SY. Plant stomata function in innate immunity against bacterial invasion. Cell. 2006;126:969–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duncan DB. Multiple range and multiple ‘F’ tests. Biometrics. 1955;11:1–42. doi: 10.2307/3001478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.