Abstract

A factor contributing to the pathogenicity of Bacteroides fragilis, the most common anaerobic species isolated from clinical infections, is the bacterium's extreme aerotolerance, which allows survival in oxygenated tissues prior to anaerobic abscess formation. We investigated the role of the bacterioferritin-related (bfr) gene in the B. fragilis oxidative stress response. The bfr mRNA levels are increased in stationary phase or in response to O2 or iron. In addition, bfr null mutants exhibit reduced aerotolerance, and the bfr gene product protects DNA from hydroxyl radical cleavage in vitro. Crystallographic studies revealed a protein with a dodecameric structure and greater similarity to an archaeal DNA protection in starved cells (DPS)-like protein than to the 24-subunit bacterioferritins. Similarity to the DPS-like (DPSL) protein extends to the subunit and includes a pair of conserved cysteine residues juxtaposed to a buried dimetal binding site within the four-helix bundle. Compared to archaeal DPSLs, however, this bacterial DPSL protein contains several unique features, including a significantly different conformation in the C-terminal tail that alters the number and location of pores leading to the central cavity and a conserved metal binding site on the interior surface of the dodecamer. Combined, these characteristics confirm this new class of miniferritin in the bacterial domain, delineate the similarities and differences between bacterial DPSL proteins and their archaeal homologs, allow corrected annotations for B. fragilis bfr and other dpsl genes within the bacterial domain, and suggest an evolutionary link within the ferritin superfamily that connects dodecameric DPS to the (bacterio)ferritin 24-mer.

INTRODUCTION

Bacteroides fragilis is a strict anaerobe that comprises approximately 1 to 2% of the normal intestinal flora in humans. While normally present as a commensal bacterium in this reducing environment, it is also the pathogenic anaerobe most frequently isolated from intra-abdominal infections, abscesses, and blood (27, 57, 58). Factors contributing to the pathogenesis of B. fragilis include resistance to oxidative stress and extreme aerotolerance, each of which is an important virulence factor for extraintestinal infections (61).

A significant pathway for the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is dependent upon the presence of free Fe2+, where Fe2+ and O2 react to form the toxic superoxide anion (19, 37). Biologically, superoxide is then converted to H2O2 and O2 by the action of superoxide dismutase (69) or superoxide reductase (43). Then, via the Fenton reaction, the hydrogen peroxide may react with remaining Fe2+ to produce the hydroxyl radical (HO·), the most toxic of all ROSs. Management of the intracellular iron pool is thus an important facet in the control of oxidative stress in virtually all organisms.

One strategy for limiting the availability of free iron is adopted by ferritin, bacterioferritin, and DNA protection in nutrient-starved cells (DPS) protein (31, 37, 64). These members of the ferritin superfamily utilize oxygen or hydrogen peroxide for the oxidation of Fe2+, producing an insoluble iron oxide within the hollow core of these oligomeric proteins. By sequestering iron in the core, these proteins protect the cell from oxidative damage by simultaneously lowering the cellular levels of Fe2+ and either H2O2 or O2. For these reasons, the roles of ferritin (ftnA) and DPS in the B. fragilis oxidative stress response have been investigated in detail (33, 49–52, 61). However, in addition to ferritin and DPS, B. fragilis has a bacterioferritin-related gene, bfr, and a recent expression microarray study shows that expression of the bfr gene is significantly induced by exposure to air, suggesting that it might also help protect against ROS (61).

Further interest in B. fragilis bfr and its gene product stems from a study suggesting that it might actually be more closely related to the archaeal DPS-like (DPSL) proteins and that the bfr gene product is a member of the newly identified miniferritin that is structurally distinct from both the larger ferritin and bacterioferritin 24-mers and dodecameric DPS (18, 28). Like DPS, the archaeal DPSL proteins are expressed in response to oxidative stress, adopt the overall fold of the DPS subunit, and form dodecameric (12-mer) cage-like particles (28, 40, 47, 67). However, unlike DPS, where the ferroxidase site is located at the subunit interface, DPSL proteins contain a di-iron carboxylate binding site buried within the four-helix bundle of each subunit, much like ferritin and bacterioferritin. Archaeal DPSL proteins are further distinguished by a pair of conserved cysteine residues, apparently unique to the DPSL proteins, that are juxtaposed to the bacterioferritin-like dimetal binding site. This cysteine pair and the bacterioferritin-like ferrioxidase center, all housed within a dodecameric oligomer, are hallmarks of the archaeal DPSL proteins and can be observed in the primary sequence as the thioferritin motif (28). Together, these features differentiate DPSL as a new member of the ferritin superfamily.

Interestingly, the DPSL thioferritin motif is also found in every green sulfur bacterial genome sequenced to date and in several species of Bacteroides, including the B. fragilis bacterioferritin-related, or bfr, gene product (15, 28). The original bfr annotation appears to stem from the similarity between the bacterioferritin and DPSL dimetal binding sites. However, this bacterioferritin-related protein sequence lacks the conserved methionine residues that coordinate the heme iron in bacterioferritins. All other proteins displaying the DPSL motif, i.e., conserved domain cd01052, also lack these methionines (28, 42). This suggests that the bfr gene product may in fact be a bacterial counterpart to the archaeal DPSL proteins and that the occurrence of this newly described miniferritin might extend into the bacterial domain of life.

Finally, there is a paucity of information on the oxidative stress response of anaerobic bacteria, and nearly nothing is known of the mechanisms that they use to manage their iron pools. For these reasons, we have explored the role of bfr and its associated gene product, which we designate B. fragilis DPSL (BfDPSL), in the B. fragilis oxidative stress response. We have characterized bfr mRNA levels in response to O2, H2O2, inorganic iron, and growth state and show that bfr null mutants displayed reduced aerotolerance. In addition, we show that BfDPSL has DNA protection activity in vitro and present the findings of crystallographic studies that confirm a DPS-like protein structure, but one that shows important differences in comparison to the archaeal DPSL proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of deletion mutant strains.

B. fragilis strain 638R was the wild type (WT) strain used for expression and mutational analyses. Strains were grown in brain heart infusion (BHIS) broth that was supplemented with cysteine (1 g/liter), hemin (5 mg/liter) or protoporphyrin IX (5 mg/liter), NaHCO3 (24 mM), and in some cases, FeSO4 (100 μM), as described in the text (52). Mutant strains were constructed by allelic exchange (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) as described previously using the suicide vector pFD516 and the PCR primers described in Table S1 in the supplemental material (53). For the construction of mutant BER63, 400 bp from the central portion of the ftnA gene was deleted and replaced with a 2.2-kb tetQ gene fragment. The BER74 mutant was constructed by deletion of the bfr gene from bp 152 of the coding region to 48 bp downstream of the C terminus of the coding region, and this was replaced by a 2.1-kb cefoxitin resistance gene, cfxA. The double mutant, BER75, was constructed by mobilization of the BER74 mutation construct into BER63 with selection on cefoxitin followed by subsequent screening for erythromycin sensitivity.

Oxidative stress sensitivity assays.

Disk diffusion assays to test for sensitivity to oxidative stress were performed by spreading 100 μl of an overnight culture on BHIS plates (without cysteine [BHIS-cys]), allowing the plates to dry, and then adding a sterile 6-mm filter disk to the center of the plate. Ten microliters of 2 M diamide or 10% hydrogen peroxide was added to the disk, and then the plates were exposed to air (at 37°C) for 6 h prior to anaerobic incubation. Following overnight incubation, the diameters of the zones of growth inhibition were measured, and the results are the averages from three independent experiments done in triplicate. A significant difference in inhibition of mutants compared to WT was determined by two-tail t test.

For the aerobic survival assays, overnight cultures were grown in BHIS-cys until they reached an optical density at 550 nm (OD550) of 0.5. Each strain was then serially diluted into BHIS-cys, and 5 μl was spotted onto fresh BHIS-cys agar plates and placed in an aerobic incubator at 37°C. At each time point, one plate was removed and placed into an anaerobic incubator at 37°C for at least 48 h until sufficient growth on the plate was observed.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis.

RNA was harvested from exponential- and stationary-phase cultures grown in BHIS with protoporphyrin IX and FeSO4, as indicated in the text. Cultures were either kept anaerobic or exposed to air with shaking for 1 h. RNA was isolated using the hot acid-phenol method (53). Fifty micrograms of total RNA was precipitated with ethanol, and contaminating DNA was removed by treatment with Turbo DNA-free DNase (Ambion). For synthesis of cDNA, 0.75 μg of RNA was added to reaction mixtures containing 10 ng/μl random hexamers, 0.5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, first-strand buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 1 μl Superscript II RNase H reverse transcriptase I; reaction mixtures were incubated at 42°C for 50 min; and Superscript II was heat inactivated by incubating the reaction mixtures at 70°C for 15 min.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was performed as described previously using a Bio-Rad iCycler instrument with real-time PCR detection (Bio-Rad) (48). Reaction mixtures contained 12.5 μl 2× iQ Sybr green Supermix, 1.5 μl of 5 μM forward primer, 1.5 μl of 5 μM reverse primer, 8.5 μl H2O, and 1 μl of cDNA template (diluted 1/100) per well. Samples were run in triplicate, and RNA samples without the addition of reverse transcriptase were run as controls to monitor for genomic DNA contamination. Relative expression values were calculated using the Pfaffl method (46). Fold induction relative to the wild type under anaerobic conditions, as indicated in the text, was determined for each gene using 16S rRNA as a reference.

Cloning, expression, and purification.

Genomic DNA from B. fragilis NCTC 9343 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The BfDPSL gene (locus tag BF3271) of NCTC 9343 is identical to the gene from strain 638R and was amplified by PCR using the primers ghg180 and ghg181. The BfDPSL gene was cloned into pDONR201 (Invitrogen) after att sites were added in a second round of PCR using primers 1-3 and attB2 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The sequence of the pDONR201-BfDPSL clone was confirmed by sequencing. The BfDPSL gene was transferred into the expression vector pDEST14 (Invitrogen).

The pDEST14-BfDPSL vector was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)RIL (Stratagene) for expression of wild-type untagged BfDPSL protein. Cells were grown to an OD600 of 2.0, and BfDPSL protein expression was induced by addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 500 μM. At 4 to 6 h after induction, cells were pelleted and frozen at −80°C. Growth medium contained 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol, 3.5 g/liter KH2PO4, 5 g/liter K2HPO4, 3.5 g/liter (NH4)2SO4, 0.5 g/liter MgSO4 · 7H2O, 5 g/liter yeast extract, 30 g/liter dextrose, 5.9 μM FeCl3, 0.84 μM CoCl2, 0.6 μM CuCl2, 1.5 μM ZnCl2, 0.8 μM NaMoO4, and 0.8 μM H3BO3.

Cells were resuspended (0.2 g/ml) in lysis buffer (1 M NaCl, 20 mM bis-Tris HCl, pH 6.5, 100 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]) and lysed with a microfluidizer (Microfluidics). Cellular debris was pelleted (20 min, 30,000 × g, 4°C), and the supernatant was heat treated (10 min at 65°C). The sample was centrifuged again (20 min, 30,000 × g, 4°C), and 106 g/liter (NH4)2SO4 was added to the supernatant. After centrifugation (20 min, 30,000 × g, 4°C), the supernatant was bound to phenyl Sepharose (GE Healthcare). After washing with 800 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM bis-Tris HCl, pH 6.5, protein was eluted with an 800 to 0 mM (NH4)2SO4 gradient. Fractions were analyzed on 10% SDS Tris-Tricine gels. Fractions containing BfDPSL were pooled and diluted 1:5 into 0.15 M NaCl, 20 mM bis-Tris HCl, pH 6.5, and loaded onto a HiTrap Q column (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with 0.15 M NaCl, 20 mM bis-Tris HCl, pH 6.5, and eluted with a gradient of 0.15 to 0.6 M NaCl. Fractions containing BfDPSL were pooled, concentrated by ultrafiltration to 5 mg/ml, and applied to a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 0.3 M NaCl, 20 mM bis-Tris HCl, pH 6.5. BfDPSL was concentrated to 15 mg/ml and stored at 4°C or frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Protein concentrations were determined with the Bradford assay using bovine serum albumin as a standard (9).

E. coli DPS (EcDPS) was overexpressed from pET-EcDPS in BL21(DE3)RIL cells by IPTG induction, using conditions similar to those used for BfDPSL overexpression. Cells were lysed by a French press in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM PMSF. Insoluble material was pelleted (20 min, 30,000 × g, 4°C), ammonium sulfate was added to the supernatant (390 g/liter), and the mixture was stirred 30 min at 4°C. Precipitated protein was pelleted as described above and resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 2 M NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA. The supernatant was dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 20 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0, 0.5 mM EDTA, which causes DPS to precipitate. The DPS pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 300 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA. After a clarifying spin, the protein was bound to a Mono S column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM bis-Tris, pH 6.5, 250 mM NaCl, and eluted with a 250 mM to 1 M NaCl gradient. Fractions containing DPS were pooled, concentrated, and applied to a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM bis-Tris, pH 6.5, 300 mM NaCl. The peak fraction was concentrated to 11 mg/ml and stored at 4°C or frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Antisera and Western hybridizations.

Imgenex (San Diego, CA) was supplied with purified BfDPSL for the production of rabbit anti-BfDPSL antiserum that was used for Western blotting. Samples for Western blotting were obtained from exponential- and stationary-phase cultures grown in BHIS supplemented as described in the text and either kept anaerobic or exposed to atmospheric oxygen with aeration for an hour. Cultures were centrifuged and stored at −80°C. Protein concentration was determined using Bio-Rad Better Bradford assay reagents. Samples were adjusted to equal amounts of protein, and then each sample was added to loading buffer containing dye in a total volume of 20 μl, boiled for 10 min, allowed to quickly cool on ice, and then loaded onto a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, probed with primary antibody, and then labeled with an alkaline phosphatase secondary antibody, and bands were visualized using chromogenic detection with nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolylphosphate. Digital densitometric analysis of photographic images was performed using ImageQuant software (Amersham Bioscience) to estimate relative band intensity. For these analyses, SDS-polyacrylamide gels in which the total protein concentration of samples was equalized over a range of from 0.8 to 25 μg of protein were tested. Following chromogenic development of the blots, densitometric measurements from at least 3 independent gels were obtained.

Particle characterization.

The oligomeric state was routinely estimated using calibrated Superdex 75 HR10/30 and Superdex 200 HR 10/30 columns (GE Healthcare) run at 25°C on a fast-performance liquid chromatography system with a UV monitor. The molecular mass of the dimer peak was verified by size exclusion chromatography (SEC; Wyatt WTC-0305S column) with inline multiangle light scattering (MALS; Wyatt HELIOS 8) and refractive index (Wyatt Optimus T-rEX) detectors (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Samples were run at 25°C in 20 mM bis-Tris HCl, pH 6.5, 300 mM NaCl. The mass was calculated with the ASTRA (version 5.3.14) software package (Wyatt Technology) using a dn/dc value of 0.185 (7). Using the concentrated material, the particle size was estimated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Leo 912AB TEM; Oberkochen, Germany) with a microscope operating at 120 keV. Samples for TEM were stained with 2% uranyl acetate.

DNA protection assay.

Assays were performed as described previously (8) with the following modifications. BfDPSL and EcDPS were exchanged by SEC into 20 mM bis-Tris HCl, pH 7.0, 300 mM NaCl. DNA binding reaction mixtures contained 36 μM protein (subunit basis), 18 nM plasmid, 20 mM bis-Tris HCl, pH 7.0, 50 mM NaCl, and were incubated for 30 min at 22°C. For DNA protection, 144 μM FeSO4 and 10 mM H2O2 were added 5 min after mixing protein and DNA. The ratio of Fe2+ to BfDPSL was thus 4 atoms per subunit, or 48 atoms per dodecamer. Where indicated, protein/DNA complexes were disrupted by addition of SDS to 2% and incubation at 80°C for 3 min. Samples were run on 0.8% agarose gels in TAE (Tris-acetate-EDTA) buffer and stained with ethidium bromide.

Mineralization assay.

Iron was added in small aliquots [0.5 μl of 0.1 M (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 (FAS) dissolved in deaerated H2O] to 22 μl of protein (1.2 × 10−8 moles of subunit) in 0.1 M bis-Tris, pH 6.5, 0.3 M NaCl at 22°C. E. coli DPS was used as a positive control, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a negative control. Nine aliquots of FAS were added over 90 min, for a total iron loading of 4.5 × 10−7 moles or 450 Fe atoms per dodecamer. For mineralization reactions with H2O2 as oxidant, aliquots (0.5 μl of 50 mM H2O2) were added 2 to 3 min after each FAS addition; and the reaction was performed within a Coy anaerobic glove box using deaerated solutions. For assays using O2 as oxidant, aliquots of deaerated FAS were added to protein under standard atmospheric conditions. Ten minutes after the final FAS addition, 1.5 μl of 1.3 M sodium citrate, pH 6.0, was added to chelate residual iron. Mineralized proteins were then visualized by Prussian blue stain, as shown by Allen et al. (1). Briefly, reaction mixtures were loaded onto a nondenaturing 0.8% agarose gel (20 μg protein per lane) and electrophoresed at 15°C. The electrophoresis buffer and gel contained 0.1 M Tris-acetate, pH 8.5, 0.3 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 20% (wt/vol) glycerol. The gel was first stained with Prussian blue (2.5% [vol/wt] K4Fe(CN)6 · H2O, 10% [vol/vol] HCl) to visualize iron and then stained with Coomassie blue to visualize protein.

Crystallization and data collection.

BfDPSL was crystallized by vapor diffusion in hanging drops at 22°C. Two microliters of protein solution (13 mg/liter) was added to 2 μl of crystallization solution containing 0.1 M Tris HCl, pH 8.5, 0.25 M MgCl2, 16% polyethylene glycol 4000, 2% (wt/vol) benzamidine HCl, and 20% glycerol. The drop was placed over 1 ml of well solution that was identical in composition to the crystallization solution, except that benzamidine HCl was omitted. Crystals appeared within 2 to 4 days. Crystals were then frozen by plunging into liquid nitrogen. A single data set to 2.3-Å resolution was collected at the peak wavelength of the zinc K edge (1.282 Å) on Stanford Synchrotron radiation light source (SSRL) beam line 9-2 (Table 1). The data were integrated and reduced in space group P213 using the HKL2000 package (44).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Parameter | Value(s) |

|---|---|

| Data collection statistics | |

| Space group | P213 |

| Unit cell parameters, a, b, c (Å) | 129.695 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.2822 |

| Resolution range (Å)a | 50.00–2.30 (2.38–2.30) |

| Total no. of reflections | 117,520 |

| No. of unique reflections | 32,431 |

| Total no. of possible unique reflections | 32,561 |

| Redundancy | 3.6 |

| Data coverage (%) | 99.6 (99.4) |

| Mean I/sigma I | 17.5 (2.9) |

| Rsym (%)b | 7.7 (24.4) |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 37.00–2.30 |

| Rcryst (%)/Rfree (%)c | 19.5/22.3 |

| Coordinate error (Å)d | 0.170 |

| Real space CCe | 0.951 |

| RMSDf from ideality, bonds (Å)/angles (°) | 0.011/1.134 |

| Ramachandran plot, favored/outliers (%)g | 98.6/0.0 |

| Avg residual B values (Å2) | 34.822 |

| PDB accession no. | 2VZB |

Numbers in parentheses refer to the highest-resolution shell.

Rsym = 100 · ΣhΣi |Ii(h) − 〈I(h)〉|/ΣhI(h), where Ii(h) is the ith measurement of the hth reflection, and 〈I(h)〉 is the average value of the reflection intensity.

Rcryst = S||Fo| − |Fc||/S|Fo|, where Fo and Fc are the structure factor amplitudes from the data and the model, respectively. Rfree is calculated similarly, using 5% of the structure factors held back as a test set.

Based on maximum likelihood.

Correlation coefficient (CC) is between the model and the electron density map calculated in the conventional way using sigma A w eighted Fourier coefficients (2mFo − DFc).

RMSD, root mean square deviation.

Calculated using the MOLPROBITY server (24).

Structure determination and refinement.

Initial phases to 3.0 Å were found by molecular replacement using the COMO program (35) with a search model derived from Sulfolobus solfataricus DPSL (SsDPSL). The CHAINSAW program (21) was used to modify the SsDPSL subunit (Protein Data Bank [PDB] accession number 2CLB), and the successful search model contained four copies of the modified subunit. The four subunits in the asymmetric unit lie along a crystallographic 3-fold axis and in conjunction with two adjacent asymmetric units form a dodecameric particle in the crystal lattice. Phases were extended to 2.3 Å using the RESOLVE program (63) with noncrystallographic symmetry averaging, solvent flattening, and histogram matching. The resulting phases yielded an easily interpretable electron density map with two strong peaks for the metal positions in the dimetal binding site. These positions were modeled as iron atoms, consistent with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) data (Energy Laboratories, Billings, MT) from the purified protein that indicated 1.2 Fe atoms per BfDPSL subunit, although zinc was also present in smaller amounts (0.3 Zn atoms per subunit). A third putative metal position on the inside surface of the particle (site C) was assigned to Mg, as MgCl2 is present in the crystallization solution and generally adopts the observed octahedral coordination. Anomalous difference maps provided no evidence for iron or zinc at this position. In contrast to Mg, placement of water at this position resulted in a significant residual difference density. Iterative rounds of manual model rebuilding with the COOT program (21) and refinement with the REFMAC5 program (21) yielded a final BfDPSL model with Rwork equal to 19.5% and Rfree equal to 22.3%. Noncrystallographic restraints were used in refinement. The MOLPROBITY server was used for structure validation (23). Molecular graphics figures were prepared with the PyMOL tool (24). Electrostatic surface potential was calculated with the adaptive Poisson-Boltzmann solver (APBS) using a temperature of 310 K, protein and solvent dielectric constants of 2 and 80, and 150 mM monovalent salt concentration (6). Metal ions were excluded from the APBS calculations.

Protein structure accession number.

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for BfDPSL have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank under accession number 2VZB.

RESULTS

Oxidative stress and growth phase control of bfr.

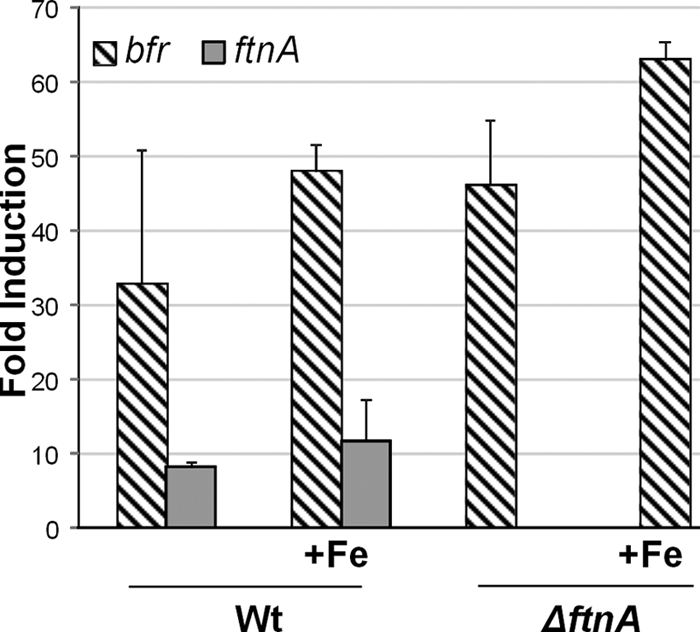

The bfr gene product, which we refer to as BfDPSL, is one of three potential iron storage proteins encoded within the B. fragilis genome (bfr, ftnA, dps). In a previous study on the B. fragilis transcriptome, it was observed that while expression of bfr is not induced by H2O2, it was induced following exposure to air for 1 h, suggesting a role in managing oxidative stress (61). In order to begin to understand its role in iron homeostasis and aerotolerance, bfr transcriptional regulation was examined in more detail and was compared to expression of ftnA, whose role in B. fragilis oxidative stress has been previously characterized (52, 61). In log-phase cultures, both genes were induced after exposure to air. Air exposure increased bfr and ftnA expression by 35- and 8-fold, respectively (Fig. 1). When cultures were grown in the presence of excess iron (added to medium in the ferrous form) and then exposed to air, there was a further 15-fold increase in bfr mRNA (relative to wild type), while a more modest 4-fold increase was observed for ftnA. There was no noticeable effect on expression of either gene when excess iron was added to anaerobic cultures (data not shown). Aerobic induction of bfr was also observed at the protein level by comparing anaerobic and aerobic cultures using polyclonal anti-BfDPSL antibody. As shown in the Western blot in Fig. 2, there was a 1.8 (±0.2)-fold increase in the amount of BfDPSL when cultures of the wild-type strain were exposed to air compared to that when the cultures were anaerobic. The increase in BfDPSL protein did not match the larger increase in transcription, but this may be due to posttranscriptional control or the limited availability of resources for protein synthesis under the growth-restrictive, aerobic conditions.

Fig 1.

Effect of aerobic exposure on bfr and ftnA expression in the WT and ΔftnA mutant strains. Exponential-phase cultures were exposed to air for 1 h, and total RNA was extracted and used in quantitative RT-PCRs with primers for the bfr and ftnA genes. Fold induction was determined from baseline values obtained for an exponential-phase, anaerobic culture of the wild-type strain grown in BHIS with protoporphyrin IX. +Fe, supplementation of medium with FeSO4 (100 μM). bfr (striped bars) and ftnA (gray bars) expression was determined by triplicate assays from two independent RNA samples.

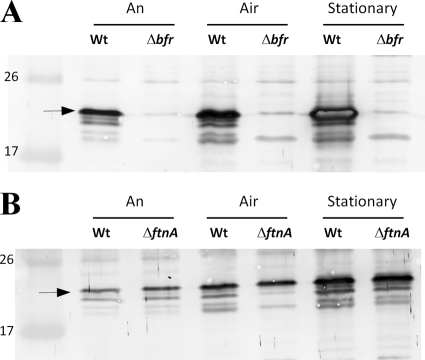

Fig 2.

Growth phase and aerobic exposure modulate expression of BfDPSL. Cultures of the WT and bfr mutant (A) or WT and ftnA mutant (B) were grown anaerobically to mid-logarithmic phase (An), exposed to air for an hour (Air), or allowed to grow anaerobically for 24 h into stationary phase (Stationary). Growth medium was supplemented with protoporphyrin IX and FeSO4. The cells were then harvested, equal amounts of protein (2.5 μg [A] or 1.25 μg [B]) were electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and Western hybridization was performed using BfDPSL polyclonal antibody. The arrow to the left of the blot indicates the BfDPSL monomer at 19.6 kDa. The molecular mass marker shows the 26- and 17-kDa proteins in the first lane.

Growth phase is known to be important for the control of both bacterioferritin and DPS in many bacteria, although it is not a major regulator of the archaeal Sulfolobus solfataricus DPSL (SsDPSL). Results in Fig. 2B indicate that there was a 3.8 (±1.4)-fold increase in the amount of BfDPSL present in stationary-phase cultures of B. fragilis. The levels of bfr mRNA in these stationary-phase cultures increased slightly, but statistically, they were not significantly greater than those in the mid-logarithmic-phase anaerobic cultures (data not shown). Thus, the accumulation of BfDPSL in stationary phase may suggest that the protein is relatively stable and not subject to rapid degradation.

The bfr gene product protects against oxidative stress.

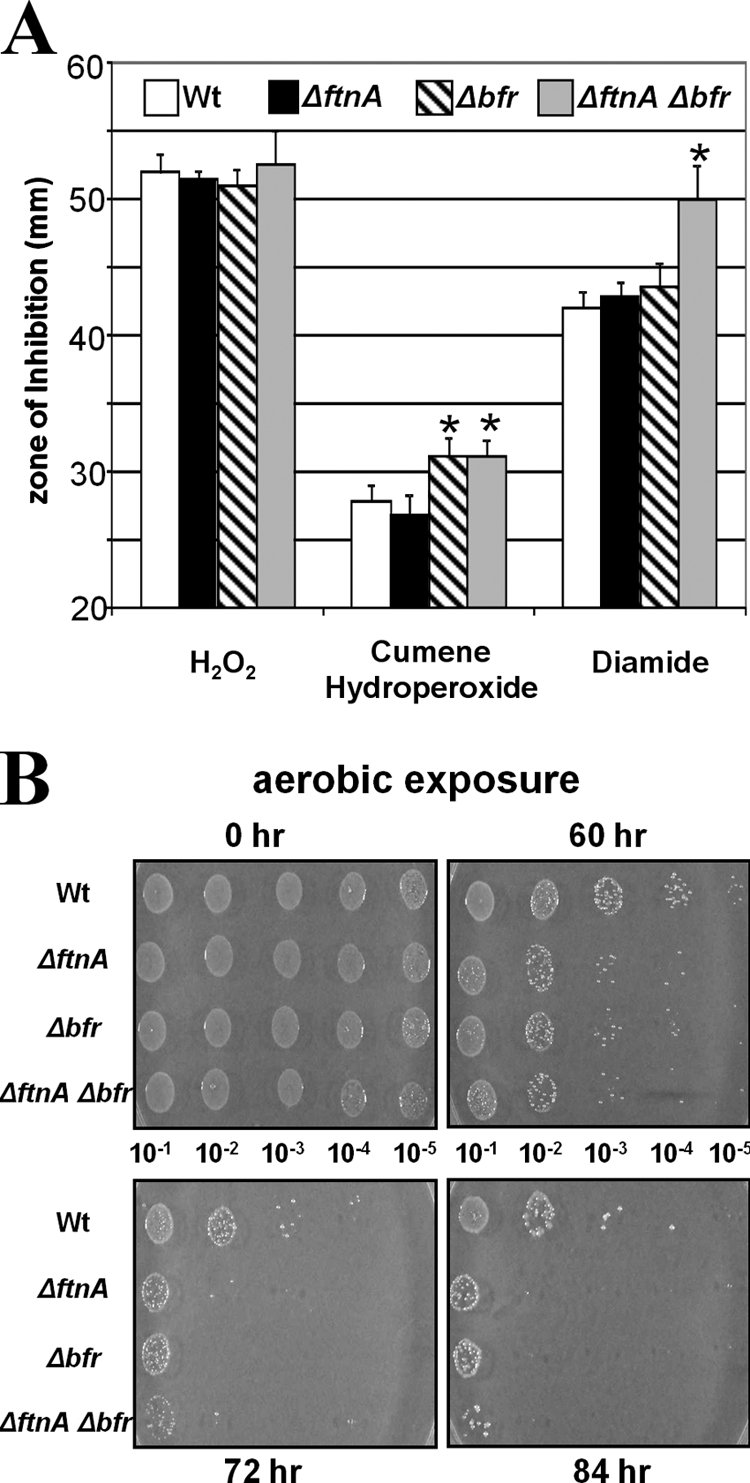

The results from studies on transcriptional regulation of bfr thus suggested that it has a role in protection against oxidative stress. We made bfr, ftnA, and double bfr ftnA mutants and examined their phenotypes in several oxidative stress assays. Since both genes are monocistronic (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), there is little likelihood that mutations will be polar on the downstream genes. As shown in the disk diffusion assays, Fig. 3A, neither single mutation resulted in an obvious phenotype with H2O2 or diamide, but we did note that the bfr and the double mutant had somewhat greater sensitivity to cumene hydroperoxide. The double mutation in the bfr ftnA mutant strain resulted in a significant increase in sensitivity to diamide but not to H2O2 (Fig. 3A). The weak phenotype against H2O2 may be due to the fact that the catalase in these strains is highly active and may mask the phenotype. A second measure of resistance to oxidative stress was obtained in the long-term aerobic survival experiment, in which strains were exposed to aerobic conditions for up to 84 h (Fig. 3B). The wild-type parental strain was able to survive for more than 84 h, but the bfr and ftnA mutants lost viability much sooner and there was a difference of 2 orders of magnitude in survival after about 60 h of aerobic exposure. The double ftnA bfr mutant was somewhat more sensitive to these conditions than either single mutant strain in this assay.

Fig 3.

Sensitivity of the wild-type, ΔftnA, Δbfr, and ΔftnA Δbfr strains to oxidative stress. (A) Growth inhibition was measured on agar plates as the diameter of the growth inhibition zone around the stress agent. Asterisks, a statistically significant difference from WT (P < 0.001). (B) Sensitivity of strains to exposure to air was tested by diluting cultures as indicated and spotting 5 μl of each dilution on a plate. The plates were then exposed to air in a 37°C incubator for 0, 60, 72, or 84 h, followed by anaerobic incubation for 2 days to determine growth.

The observation that a double mutant lacking both ftnA and bfr had a more pronounced phenotype in some of the oxidative stress assays suggested that there is complex interplay between the roles of the different ferritin family proteins in B. fragilis. As shown in Fig. 1, there was a tendency for an increase (about 8- to 10-fold) in bfr expression in the ftnA mutant strain background relative to the wild-type strain, but this increase was not observed at the protein level. Results in Fig. 2B suggest that levels of BfDPSL in the ftnA mutant are similar to those in the wild-type strain during stress. Likewise, there was no change in the accumulation of BfDPSL in the wild-type strain compared to the ftnA mutant in stationary-phase cultures. These results suggest that the ftnA mutant did not directly compensate for the loss of FtnA with increased synthesis of BfDPSL during aerobic exposure or stationary phase. It is also worth noting that there was no evidence for increased transcription of the ftnA gene in the bfr mutant (data not shown).

Biochemical characterization.

Recombinant BfDPSL was expressed in E. coli and purified to homogeneity. The purified protein behaves as a dimer on the size exclusion column, and this has been confirmed with SEC-MALS (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). However, at higher concentrations (13 mg/ml), spherically shaped particles with diameters of ∼95 Å were seen by negative-stain transmission electron microscopy (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), suggesting assembly of a dodecameric particle like that expected for DPS or DPSL, as opposed to the 24-mer common to ferritin and bacterioferritin. While members of the ferritin superfamily are often found as stable oligomers, their assembly states can also be dependent upon changes in pH, salt concentration, metal ions, and temperature (8, 12, 14, 20, 30). However, despite surveying a variety of protein concentrations and buffer conditions, we were unable to identify conditions that give a stable dodecamer on the SEC column. This suggests that while BfDPSL is present in solution predominantly as a dimer, it is in dynamic equilibrium with higher-order oligomers, including the dodecamer, and is capable of rapid assembly and disassembly.

Many members of the ferritin superfamily sequester iron as an insoluble oxide inside the oligomeric particle. We were thus interested in whether BfDPSL possessed a similar activity. While our positive control, E. coli DPS, displayed robust mineralization activity using H2O2 as the oxidant (and minimal activity using O2), we did not observe mineralization activity with BfDPSL using either O2 or H2O2 as the oxidant (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The lack of mineralization activity might be a consequence of the primarily dimeric form of DPSL that would be present in these assays. Alternatively, this may be a consequence of the disulfide or the nonnative metals or mixed metal occupancy at the dimetal binding site, perhaps due to heterologous expression of BfDPSL in E. coli. ICP-MS analysis of the purified protein shows 1.2 Fe atoms and 0.3 Zn atom per subunit. Attempts to remove the copurifying Zn have, to date, resulted in the production of insoluble protein.

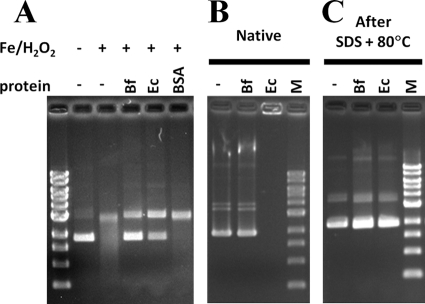

We next examined the ability of the predominantly dimeric BfDPSL to protect DNA from strand cleavage in vitro in the presence of Fe2+/H2O2. As shown in Fig. 4A, the protective activity of BfDPSL is comparable to that of E. coli DPS, which was used as a positive control, and greater than that of BSA, which was used as a negative control. As expected, E. coli DPS formed a complex with DNA that prevented it from entering the gel (11), but BfDPSL did not appear to bind DNA under the conditions of the DNA protection assay (Fig. 4B).

Fig 4.

DNA protection by BfDPSL. BfDPSL protects DNA from hydroxyl radical cleavage but does not retard the mobility of DNA under the same conditions as EcDPS. (A) DNA protection. BfDPSL was evaluated for DNA protection activity by incubation with supercoiled plasmid prior to exposure to FeSO4 and H2O2. Purified EcDPS was used as a positive control, and BSA was used as a negative control. DNA integrity was assayed by electrophoresis after DNA/protein interactions were disrupted by SDS/heat treatment. Without protein protection, the DNA is degraded and appears as a smear on the gel. (B) BfDPSL was evaluated for DNA binding activity by gel retardation assay, with EcDPS as a positive control. After addition of BfDPSL or EcDPS to supercoiled plasmid, samples were analyzed by electrophoresis without further treatment (B) or after DNA/protein interactions were disrupted by SDS/heat treatment (C). In panel B, ethidium bromide staining is visible in the well, indicating that the EcDPS/DNA complex does not migrate into the gel. In panel C, the DNA migrates at the expected mobility after the complex is disrupted. Bf, BfDPSL; Ec, EcDPS; −, no protein added; M, molecular mass standard.

Structural similarities between BfDPSL and SsDPSL.

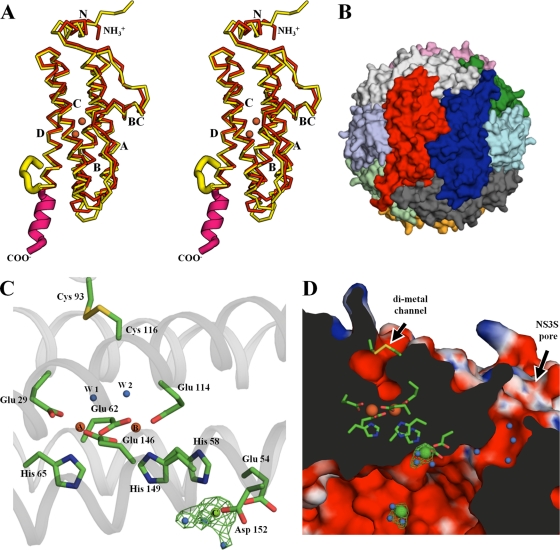

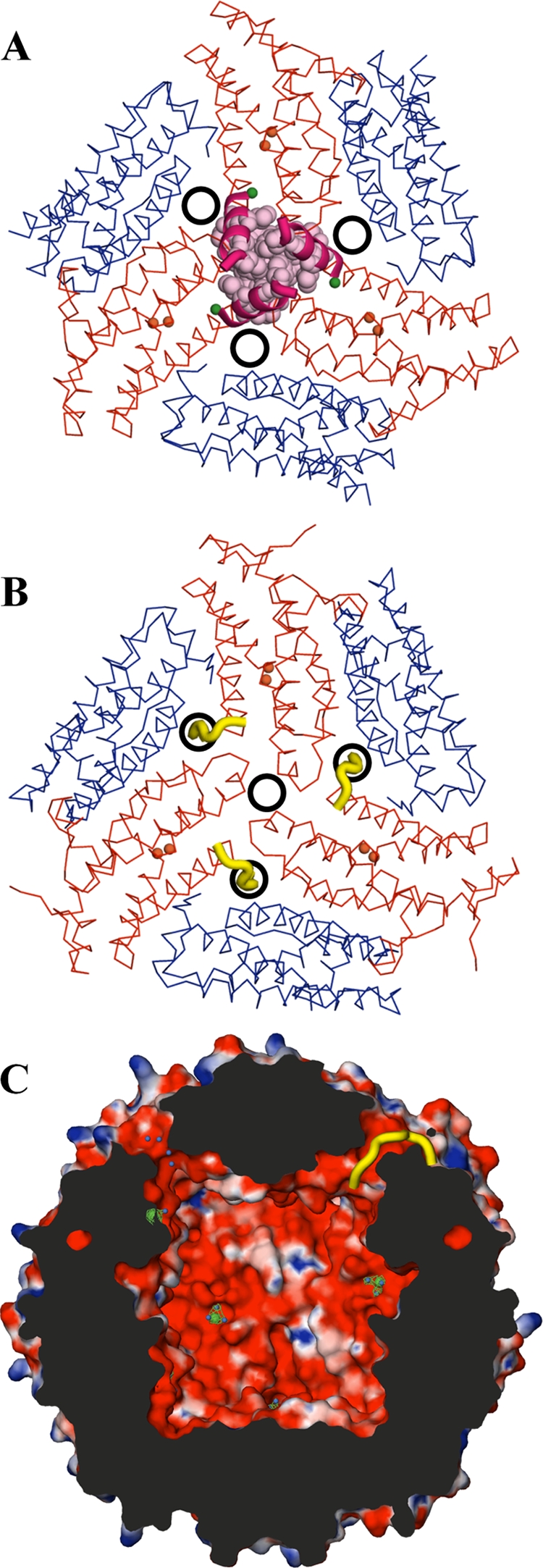

The purified BfDPSL was crystallized, with the crystals diffracting to 2.3-Å resolution. Consistent with the particles seen by electron microscopy (EM), self-rotation functions suggested the presence of a dodecameric DPS-like assembly. We thus used the SsDPSL protein as the molecular replacement search model to successfully phase the structure. As hypothesized, the resulting structure of BfDPSL (PDB accession number 2VZB) revealed a dodecameric assembly that is in many ways similar to SsDPSL. Superposition of the BfDPSL and SsDPSL subunits yields 155 equivalent C-α positions with a root mean square deviation of 1.2 Å. Like SsDPSL, the BfDPSL subunit folds into a four-helix bundle that is elaborated upon by the addition of the BC and N-terminal helices (Fig. 5A). Consequently, at the quaternary level, BfDPSL forms a hollow dodecameric shell (external diameter, ∼95 Å; Fig. 5B) with a 23-point group symmetry that encloses a negatively charged central cavity approximately 50 Å in diameter.

Fig 5.

Structure of BfDPSL subunit. (A) Stereo panel. BfDPSL (PDB accession number 2VZB, red/magenta) and SsDPSL (PDB accession number 2CLB, yellow) have been superimposed (36). The structures show significant similarity from the N-terminal helix through helix A, helix B, the BC loop with its short BC helix, helix C, and much of helix D. The structures show significant differences, however, at their C termini. Also shown are the positions of the metals in the BfDPSL dimetal binding site (orange spheres). (B) The BfDPSL dodecamer is shown colored by subunit. The red subunit is in the same orientation as in panel A. (C) The BfDPSL metal binding sites. Relative to panel A, the orientation in panel C has been rotated 90° about the y and z axes. Two iron atoms (A and B) are bound in a bacterioferritin-like dimetal binding site. Two conserved cysteine residues, present as a disulfide, are juxtaposed between the solvent channel (D) and the exterior of the particle. W1 and W2, two of the eight ordered waters in the channel, which are bound to iron A and iron B, respectively, and positioned 7.7 Å from the disulfide. At the lower right, a single magnesium atom (green, labeled C) is bound to the inner surface of the subunits facing the central cavity of the dodecamer (toward the bottom). The distance from metal B to metal C is 8.7 Å. The Fo − Fc electron density omit map is contoured at 4.0 σ. Three residues, His-58, Glu-54, and Asp-152, and three water molecules (blue) surround the magnesium in approximate octahedral geometry. (D) Cross section through dodecamer shell showing the relative positions of the metal binding sites, the channel to the dimetal binding site, and the major, or NS3S, pore. The channel to the dimetal binding site is immediately above the iron atoms (orange spheres) and connects to the exterior surface. The NS3S pore is to the right of the dimetal binding site, running at a 45° angle, and connecting the interior and exterior surfaces of the particle. Site C is shown on the inner surface of the dodecamer adjacent to the NS3S opening. To highlight the pore, the orientation is rotated slightly relative to panel C (30° about the y and x axes). The electrostatic surface is contoured from −15 kT/electron (red) to +15 kT/electron (blue). In the absence of metals, the channel to the dimetal binding site, the major pore (NS3S), and the interior of the particle all exhibit strong negative potential.

Structural similarity in the dimetal site.

Like SsDPSL, BfDPSL contains two metal atoms, A and B, at the center of each subunit that are coordinated by 2 histidine and 4 glutamate residues (His-65, His-149, Glu-29, Glu-62, Glu-114, and Glu-146) in a classical bacterioferritin-like dimetal binding motif (Fig. 5C; see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Distances between the two iron atoms range from 4.0 to 4.2 Å. Two waters, W1 and W2, are positioned 2.3 to 2.5 Å from the iron atoms, where they occupy the 6th ligand position and complete the approximate octahedral coordination geometry for each iron atom (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material).

Further similarity to SsDPSL is seen in a solvent-filled channel that leads from the dimetal binding site to the exterior surface of the dodecamer (Fig. 5D). This channel may allow water, hydrogen peroxide, oxygen, or iron to access the putative ferroxidase center. The channel is slightly larger in BfDPSL than in SsDPSL and contains eight ordered water molecules, including the two coordinated by the iron atoms. Also similar to SsDPSL, the two cysteine residues unique to DPSL proteins, Cys-93 and Cys-116, are juxtaposed between the exterior of the dodecameric shell and the channel leading into the dimetal binding site. There is clear electron density for a bridging disulfide bond in the B. fragilis crystal structure.

The structure of B. fragilis DPSL thus shows greater similarity to the archaeal DPSL proteins than it does to true bacterioferritins and provides definitive evidence for the existence of DPSL miniferritins in the bacterial domain of life. Hence, we chose to refer to the B. fragilis bfr gene product as B. fragilis DPSL, or BfDPSL. To our knowledge, BfDPSL is the first bacterial DPSL to be characterized and thus provides the opportunity to compare and contrast structural features of the bacterial and archaeal DPSL proteins.

Unique features of bacterial DPSL. (i) A third metal binding site.

In addition to the dimetal binding site discussed above, a third metal binding site is found in BfDPSL. This C-site metal, which is not found in SsDPSL, is located on the inner surface of the dodecamer, approximately 7 Å from where the major pore (discussed below) opens into the interior of the particle (Fig. 5D). Fo − Fc difference maps (Fig. 5C and D) show strong (10 σ) electron density at this position, suggestive of a cation with octahedral coordination by His-58, Glu-54, Asp-152, and 3 water molecules. An Mg2+ ion was modeled at this position because the crystallization solution contained 0.25 M MgCl2 and anomalous difference maps do not indicate any iron or zinc content at this site. Interestingly, these three C-site residues are strictly conserved in 44 bacterial DPSL-type sequences, while they are uniformly absent from the archaeal DPSL-type sequences (Fig. 6, green residues; see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). Notably, the relative location of the bacterial C-site metal seen in BfDPSL is reminiscent of the C-site iron position in E. coli ferritin (32, 37, 59) and the third iron site on the inner surface of bacterioferritin (22). Although the anomalous difference data rule out Fe at this site in the BfDPSL crystal structure, iron might access the site, in vivo, in several ways. The most obvious route is via the major pores in the BfDPSL dodecamer. Alternatively, as suggested by Macedo et al. (41) and others (10) for bacterioferritin, concerted movement of several side chains might allow iron to move between the B and C sites. In either event, the C site might serve to facilitate movement of iron through the protein shell and/or as a nucleation center for iron mineralization.

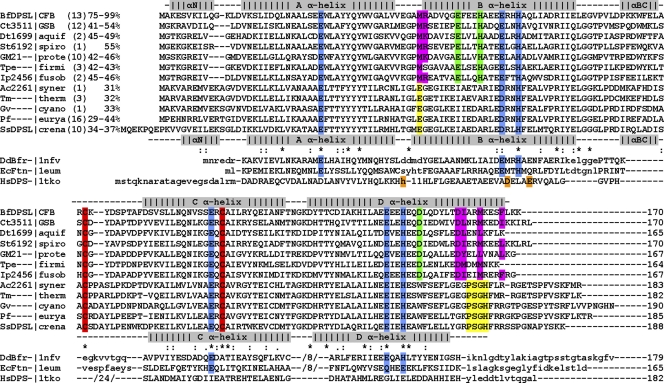

Fig 6.

Representative DPSL sequence alignment. A representative DPSL sequence from each of 12 different phyla was aligned with ClustalW (34, 65). The secondary structure elements in BfDPSL and SsDPSL are shown above and below the sequences, respectively, followed by ferritin (EcFtn), bacterioferritin (DdBfr), and DPS (HsDPS) sequences, where minor adjustments were made in order to align known secondary structural elements. The DPSL sequences clearly divide into two groups: one containing a short C-terminal tail and one containing a long C-terminal tail. The short-tailed sequences predominate in mesophilic bacteria, while long-tailed DPSLs predominate in archaea and thermophilic bacteria. Both groups share the conserved thioferritin motif; the 2 cysteines are in red, and the 6 residues in the dimetal binding site are in blue. The short-tailed DPSLs contain two additional distinguishing motifs. First, residues comprising metal binding site C are strictly conserved in this group (green). Second, a pattern of hydrophobic residues consistent with an amphipathic helix (3/4 spacing) is found in the short C-terminal tail; these residues, along with Met-47 from the AB loop, form a hydrophobic core that stabilizes the cap over the C-terminal 3-fold axis (magenta). In addition, Arg-48 (or Lys) forms an interchain salt bridge with Asp-159 that also stabilizes the cap (magenta). In contrast, the long-tailed DPSLs contain the conserved PSGH motif (yellow) that functions to transit the protein shell, and in place of the hydrophobic Met-47, they prefer a glutamate residue (E; yellow), which in SsDPSL is found at the opening of the 3-fold pore. Asterisks, conserved residues in the 74 proteins containing the thioferritin motif (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). Ferroxidase active-site residues are colored blue (EcFtn, DdBfr) or orange (HsDPS). The number of DPSL sequences in each phylum is in parentheses, followed by the range of amino acid identity with BfDPSL for each phyla. The abbreviations used are followed by organism and GenBank gene identifier: BfDPSL, Bacteroides fragilis gi60682741; Ct3511, Chloroherpeton thalassium gi193215108; Dt1699, Desulfurobacterium thermolithotrophum gi325294845; St6192, Spirochaeta thermophila gi307719855; GM21, Geobacter sp. strain M21 gi253701127; Tpe, Thermoanaerobacter pseudethanolicus gi167036853; Ip2456, Ilyobacter polytropus gi310780231; Ac2261, Aminobacterium colombiense gi294101498; Tm, Thermotoga maritima gi15643326; Gv, Gloeobacter violaceus gi37523861; Pf, Pyrococcus furiosus gi18977565, SsDPSL, Sulfolobus solfataricus gi15898865; DdBfr, Desulfovibrio desulfuricans (PDB accession number 1NFV) gi220904655; EcFtn, Escherichia coli (PDB accession number 1EUM) gi15802314; HsDPS, Halobacterium salinarum (PDB accession number 1TKO) gi15791220; CFB; Bacteroidetes, GSB, Chlorobi; aquif, Aquificae; spiro, Spirochaetes; prote, Proteobacteria; firmi, Firmicutes; fusob, Fusobacteria; syner, Synergistetes; therm, Thermotogae; cyano, Cyanobacteria; eurya, Euryarchaeota; crena, Crenarchaeota.

(ii) Conformation of the C-terminal tail.

In the DPS and SsDPSL dodecamers, the N-terminal ends of three subunits come together at one end of the 3-fold axis in a set of interactions that are similar to the 3-fold interactions in ferritin. In contrast, interactions at the opposite end of the 3-fold axis involve the C-terminal ends of three subunits, giving rise to 3-fold symmetric interactions that are unique to the DPS and DPSL dodecamers.

It is here, in the C-terminal residues, that the structure of BfDPSL differs significantly from that of SsDPSL. The B. fragilis and S. solfataricus protomers superimpose well only up to Thr-158 in the D helix (Tyr-168 in SsDPSL). After this point they adopt very different conformations. In BfDPSL, the last 12 residues (Asp-159 through Lys-170) are used to extend the D helix (Fig. 5A), with all but the last C-terminal residue visible in the electron density. The BfDPSL D helix is thus significantly longer than the D helix in SsDPSL and runs along the exterior surface of the particle, toward the 3-fold axis, where it interacts with the D helices in symmetry-related subunits to form a 3-fold symmetric cone or tepee-shaped structure (Fig. 7A; see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). At the analogous position in SsDPSL, we find the entrance to the major pore (the C-terminal 3-fold pore) allowing access to the interior of dodecameric shell (Fig. 7B) (28). In BfDPSL, however, the symmetry-related D helices come together on the outside surface of the particle to cap the C-terminal 3-fold axis, preventing access to the interior of the particle via the C-terminal 3-fold pore.

Fig 7.

Conformation of the C-terminal tail, pore number, and location in DPSL subtypes. (A) Six subunits of bacterial BfDPSL are viewed looking down the C-terminal 3-fold axis. The extended D helices (magenta) come together at the center to cap the 3-fold axis. The locations of the nonsymmetric three-subunit (NS3S) pores are indicated by the three black circles surrounding the C-terminal 3-fold axis. With 4 C-terminal 3-fold axes per particle, this gives a total of 12 NS3S pores. The locations of the A and B metal sites are shown as orange spheres within the red subunits, and metal site C is shown as a green sphere. (B) Archaeal SsDPSL in the same orientation. The C-terminal tail (yellow) is in a markedly different conformation and transits the protein shell at a location equivalent to that of the NS3S pores in bacterial DPSL. While this opens a single pore at the C-terminal 3-fold, it plugs the 3 potential NS3S pores surrounding the 3-fold axis. The net result is only 4 major pores in the archaeal SsDPSL, as opposed to 12 pores in the bacterial BfDPSL. (C) Cross section from a surface representation of the BfDPSL particle colored by electrostatic potential as in Fig. 5D. Two NS3S pores transit the protein shell (top left and top right), connecting the interior and exterior surfaces of the particle. The tail of a single superpositioned SsDPSL subunit (yellow) transits the protein shell, demonstrating how a C-terminal tail in this conformation would plug any potential NS3S pore (top right of panel C).

This BfDPSL cap is stabilized by a central core of buried hydrophobic side chains, with polar and charged residues projecting outward (Fig. 7A; see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). Each helix contributes 3 residues to this hydrophobic core: Ile-160, Met-163, and Phe-167. This hydrophobic core is well conserved among bacterial DPSLs. Using PSI-BLAST (2, 56) seeded with protein sequences containing the DPSL thioferritin motif (the two conserved cysteines plus the dimetal site residues), we identified 74 DPSL proteins in the current sequence database. Figure 6 shows a representative alignment of sequences containing the thioferritin motif from 12 different phyla (a complete alignment of all sequences containing the thioferritin motif is provided in Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). The sequence alignment shows that mesophilic bacterial sequences retain hydrophobic residues at these positions, whereas the archaeal proteins do not.

The cap appears to be further stabilized by Ala-46, Met-47, and Arg-48, which are contributed by the A-B loop (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). Ala-46 and Met-47 lie at the base of the cap, where they join the hydrophobic core, while Arg-48 forms an intersubunit salt bridge with Asp-159. In contrast, SsDPSL and the other archaeal proteins do not utilize the intersubunit salt bridge and generally substitute Glu or Asp for Met-47, which adds an additional ring of negative charge to the external opening of their 3-fold C-terminal pores. In all, the conserved features of these bacterial sequences, coupled with the role of these residues in BfDPSL, suggest that the extended D helix and the cap at the C-terminal 3-fold axis are common features of these bacterial DPSL proteins.

While the long D helix in BfDPSL forms a cap, the D helix of SsDPSL is shorter and is followed by a 21-residue tail (28). This shorter D helix and extended C-terminal tail appear to be characteristic features of the archaeal DPSL proteins (Fig. 5 and 6; see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). In SsDPSL, the first seven residues of the C-terminal tail adopt a random coil structure that turns away from the 3-fold axis and passes through the protein shell into the interior of the dodecamer (Fig. 7B), where the last 14 C-terminal residues are disordered. As the tail extends into the interior, four ordered residues, Pro-Ser-Gly-His, are involved in transiting the protein shell (yellow highlights in Fig. 6 and 7B). Strikingly, these residues are conserved in the archaeal-type proteins but are absent from the bacterial sequences. This longer C-terminal tail with the embedded Pro-Ser-Gly-His sequence thus appears to be a hallmark of proteins with an internal tail.

(iii) Number and location of major pores.

The different conformations of the C-terminal tail in the SsDPSL and BfDPSL subunits result in a major difference in the structures of their respective dodecameric particles. While the major pores in SsDPSL lie at the C-terminal 3-fold, the C-terminal tail of the BfDPSL subunit caps these C-terminal 3-fold pores. However, as the 12 D helices are extended in the BfDPSL dodecamer to close the four, 3-fold C-terminal pores, 12 alternate pores are created (Fig. 7). This is because the paths taken by the 12 C-terminal tails that transit the shell in the SsDPSL dodecamer are now vacant. This is demonstrated by superposition of the S. solfataricus and B. fragilis DPSL dodecamers; the C-terminal residues in archaeal SsDPSL (yellow) superimpose on the hydrophilic pores of the bacterial BfDPSL dodecamer (Fig. 7C). These positions appear to be the major pores in BfDPSL and are located at a nonsymmetric junction of three subunits (Fig. 7A). We thus designate these nonsymmetric three-subunit (NS3S) pores. Two of the three subunits forming this pore are related by a 2-fold rotation axis, while the third subunit is positioned against the end of the first two, resulting in a pore with a minimal diameter of 4.3 Å (Fig. 7A and viewed in cross section in Fig. 5D and 7C). The relative positions of the C-terminal 3-fold, the NS3S pores, and the channels to the dimetal binding sites are shown in a surface representation of the BfDPSL dodecamer in Fig. S8 in the supplemental material. Importantly, compared to the four C-terminal 3-fold pores in SsDPSL, there are now 12 NS3S pores in the BfDPSL dodecamer (Fig. 7).

Interestingly, a similar set of NS3S pores is seen for at least one member of the DPS family, the dodecameric DpsA from Halobacterium salinarum (70). Analysis of the iron-loaded DpsA structure identifies 3 iron atoms within the H. salinarum NS3S pore (PDB accession number 1TKO), suggesting that this pore allows iron to enter the central cavity of the DpsA dodecamer. In addition, despite assembling to form a 24-mer, analogous pores are found in a bacterioferritin and several bacterial ferritins. More specifically, the NS3S pore in BfDPSL is equivalent to the B (37, 41) or MC (10) pore in the bacterioferritins from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans and Azotobacter vinelandii (38, 62) and similar pores in the ferritins from E. coli (59) and Thermotoga maritima (PDB accession number 1Z4A; S. Steinbacher et al., unpublished data).

Similar to H. salinarum DpsA, residues lining the NS3S pore in BfDPSL are largely hydrophilic and several ordered water molecules are found within the pore (Fig. 5D). Additional electron density within the pore is also consistent with the presence of a molecule of bis-Tris, the buffer used during protein purification. Surrounding the opening to the pore on the exterior surface of the dodecamer are Lys-3, Glu-77, and Val-79 from subunit A; Glu-44 and Phe-101 from subunit B; and Thr-158 from subunit C. A higher density of charged side chains surrounds the opening where it exits into the interior of the dodecamer: Gln-67, Asp-71, and Glu-75 from subunit A; Arg-48, Gln-52, and Glu-56 from subunit B; and Glu-54, Glu-148, and Asp-152 from subunit C. In conjunction with the main-chain carbonyl groups that line the wall of the pore, there is a strong net negative charge that may function to draw ferrous iron through the pore (25). Importantly, metal binding site C is present on the interior surface of the dodecamer, only 7 Å from the central axis of the NS3S pore (Fig. 5D and 7A and C).

DISCUSSION

Regulation of bfr expression.

The structural similarity between SsDPSL and BfDPSL suggests that they may have analogous functions in vivo. In this regard, an important role in the oxidative stress response is supported by transcriptional analysis of both genes. The SsDPSL transcript is upregulated in response to H2O2, whereas the BfDPSL transcript is increased 35-fold during exposure to air. Notably, there was no increase in BfDPSL mRNA during H2O2 exposure, but this may be due to the rapid induction of catalase, which is a part of the OxyR regulon in B. fragilis. Consistent with this idea, a previous expression microarray study showed a modest 4-fold induction of bfr by H2O2 in an oxyR mutant which has greatly reduced catalase activity (61). In contrast to oxidative stress, there did appear to be a difference in the response to iron levels. In S. solfataricus, the DPSL gene is induced by iron limitation. In contrast, B. fragilis bfr expression increased during growth with excess iron levels during oxidative stress, but this was not found in anaerobic cells.

The difference in the response to iron does not necessarily indicate mechanistic differences between SsDPSL and BfDPSL. The presence of 3 members of the ferritin family in the B. fragilis genome (dps, ftnA, and bfr), combined with differences in gene regulation, may simply allow the optimal deployment of a set of related activities under a variety of different conditions. Consistent with this is the observation that the bfr and ftnA mutants and the bfr ftnA double mutant displayed somewhat different phenotypes, depending on the type of oxidative stress tested in the assays (Fig. 3). In addition, the bfr and ftnA genes are regulated differently, and deletion of the ftnA gene did not directly affect expression of BfDPSL under conditions of aerobic stress or stationary phase. Differential expression of ferritin superfamily members has also been observed in other organisms, including Bacillus subtilis (5, 16, 26), Bacillus anthracis (3, 39, 45), Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (66), and Pseudomonas putida (17). Thus, as the B. fragilis dps gene is extremely responsive to peroxide or oxygen (49, 61), B. fragilis may hold the activity of BfDPSL in reserve for iron storage and/or DNA protection during the transition to stationary phase or for prolonged O2 exposure. This would be consistent with the phenotype observed for the bfr mutant in the extended aerobic exposure assay (Fig. 3B).

DNA binding, protection, and mineralization.

While we are unable to offer a satisfying explanation for DNA protection by BfDPSL, we note that E. coli DPS is thought to protect DNA in two ways. First, as discussed in the introduction, it can sequester iron oxide inside the dodecamer, reducing the concentration of both iron and reactive oxygen species. Second, as it binds and sequesters DNA, it may provide a physical barrier that limits damage. In this light, we note that dimeric forms of DPS from two other organisms have demonstrated DNA protection activity. In the first example, the dimeric form of DPS from Mycobacterium smegmatis protects DNA without apparent DNA binding (14). Ceci et al. (14) attributed the DNA protection to iron oxidation at the two ferroxidase sites which remain intact at the subunit interface of dimeric Mycobacterium DPS. Similarly, the intact ferroxidase sites within each subunit of the dimeric form of BfDPSL may provide protection in our assay. Alternatively, in the unassembled form, the negatively charged inner surface of the dimer might act to chelate a significant portion of the iron, reducing the production of reactive oxygen species. In a second example, dimeric DPS from Deinococcus radiodurans is able to protect DNA in a similar assay, but in this case the protection may be facilitated by DNA binding (30). Thus, we also consider the possibility of protective BfDPSL-DNA interactions that are not apparent in our assay; these interactions might be disrupted during electrophoresis and are therefore not visible on the gel. On the other hand, protective activity in the absence of DNA binding has been observed for several dodecameric DPS proteins, for example, DPS proteins from Listeria innocua, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and Streptococcus mutans (13, 60, 68).

In the E. coli DPS dodecamer, DNA binding activity is mediated by positively charged residues present on a flexible extension at the N terminus of the subunits (11). While the BfDPSL subunit has three lysines near the N terminus and two near the C terminus, these residues are present in helix N, the αN-αA loop, and the extension to helix D. The N and D helices in the BfDPSL dodecameric assembly do not appear to be sufficiently exposed to insert within the DNA major groove. In addition, the electrostatic surface of the dodecamer (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material) does not appear to be sufficiently positive to promote strong electrostatic interactions with the ribose phosphate backbone. These observations may explain the lack of DNA binding activity. Alternatively, BfDPSL may lack DNA binding activity under our assay conditions due to its predominantly dimeric state.

Quaternary structure.

Interestingly, while BfDPSL was predominantly a dimer in solution, it was found to assemble into a dodecamer both within the crystal and on the EM grids. Based on its similarity to other ferritins and its importance in the B. fragilis oxidative stress response, we presume that the dodecameric assembly is physiologically relevant. Importantly, recent literature for several other members of the ferritin superfamily also indicates easy dissociation into dimers or monomers in vitro (4, 8, 12, 14, 20, 30). One possible explanation for BfDPSL is that assembly might be facilitated by other proteins in vivo. For example, Sulfolobus DPSL is reported to be a part of a larger supramolecular complex (40) that also contains superoxide dismutase (SOD) and peroxiredoxin, two proteins upregulated under oxidative stress in Sulfolobus. Perhaps a similar complex may occur in Bacteroides, where SOD and several peroxidases are also upregulated following exposure to oxygen (61).

DPSL subclasses and role of C-terminal tail in ferritin superfamily.

Significant structural differences between SsDPSL and BfDPSL include differences in sequence and structure at the C terminus, the number and location of the major pores, differing sequence motifs within the A-B loop, and the presence or absence of the C-site metal binding residues. Considered together, it becomes clear that there are at least two distinct structural subclasses among DPSL proteins. We note that the division between subclasses falls largely along the boundary between the archaeal (SsDPSL) and bacterial (BfDPSL) domains, although DPSLs from the thermophilic bacteria group with the archaeal sequences.

Role of C-terminal residues in ferritin superfamily.

One of several examples of the role of the C-terminal residues in modulating the assembly and activity of ferritins is the distinctly different conformations of the C-terminal tail in SsDPSL and BfDPSL. In the 24-subunit ferritins and bacterioferritins, the C-terminal residues are present as an additional α helix that mediates interactions at the 4-fold axis (31, 41). In dodecameric DPS proteins, this short C-terminal helix is lost, with the C-terminal tail adopting a random coil arrangement on the outside of the particle (29), where, along with the N-terminal tail, it may play a role in modulating nonspecific interactions with DNA (54). In addition, the C-terminal tail in DPS has also been shown to play a critical role in stabilizing the dodecamer (54, 55). Now, in the SsDPSL and BfDPSL dodecamers, we see that the C-terminal tail can adopt two additional conformations. In the case of SsDPSL, the C-terminal tail extends through the NS3S pore into the interior of the particle. In contrast, the C-terminal residues in BfDPSL extend the D helix and cap the C-terminal 3-fold pore. In both cases, these C-terminal tails are involved in intersubunit interactions and are thus likely to stabilize their dodecameric assemblies.

Relationships in ferritin superfamily.

It is also interesting to consider the position of bacterial DPSL within the ferritin superfamily from an evolutionary point of view. It is relatively easy to imagine the loss of the disulfide and dimetal binding sites within the four-helix bundle, coupled with the appearance of metal binding sites at the subunit interfaces of the dodecameric assembly, giving rise to a bacterial DPS. Alternatively, small changes in the subunit interfaces and loss of the disulfide could give rise to a ferritin-like 24-mer, as opposed to the dodecameric DPSL. In turn, the ferritin subunit interface could be further modified to accommodate the intersubunit heme found in bacterioferritin. The DPSL structure thus seems to be a logical evolutionary intermediate within the ferritin superfamily, one that seemingly connects the bacterial DPS proteins to the larger (bacterio)ferritins (see Fig. S10 in the supplemental material). It is not clear, however, in which directions these evolutionary events might have proceeded.

In summary, we have examined the expression of the B. fragilis bfr transcript in response to oxidative stress and show that deletion of the bfr gene decreases oxygen tolerance. We have also shown that the bfr gene product, BfDPSL, protects DNA against oxidative stress in vitro. In addition, our structural studies show that BfDPSL contains many of the structural elements of the archaeal DPSL protein, including a dodecameric assembly that harbors the thioferritin motif. This extends the observation of this new class of miniferritin to the bacterial domain, where it is found in at least seven different phyla. However, the structure also highlights significant differences between the short-tailed bacterial DPSL proteins and their longer-tailed archaeal homologs. Importantly, these structural differences are clearly manifested in their respective primary sequence motifs, and these may be used to differentiate the two structural subclasses. This should facilitate proper reannotation of these bacterial DPSL proteins, which are frequently mistaken for bacterioferritins. Combined, these studies confirm a role for BfDPSL in the oxidative stress response of B. fragilis, the most commonly isolated anaerobic human pathogen. As resistance to oxidative stress is a virulence factor for B. fragilis, BfDPSL might be an attractive target for development of antibiotics against B. fragilis and other members of the Bacteroidetes, particularly since DPSL proteins have not been found in eukaryotic organisms.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the R. Gerlach, B. Bothner, and J. Peters laboratories for assistance with ICP-MS, liquid chromatography/MS, and anaerobic techniques. The assistance of Anita Parker with the Western blotting is gratefully acknowledged.

This work was supported by grants from the Public Health Service (AI40599 to C.J.S. and AI079183 to E.R.R.), by the Human Frontier Science Program (RGP61/2007 to T.D.), and by the National Institutes of Health (GM084326 to C.M.L.). Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL), a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The Macromolecular Diffraction Laboratory at Montana State University was supported, in part, by a grant from the Murdock Foundation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 October 2011

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Allen M, Willits D, Mosolf J, Young M, Douglas T. 2002. Protein cage constrained synthesis of ferrimagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 14:1562–1565 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Altschul SF, et al. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Altuvia S, Almiron M, Huisman G, Kolter R, Storz G. 1994. The dps promoter is activated by OxyR during growth and by IHF and sigma S in stationary phase. Mol. Microbiol. 13:265–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andrews SC, et al. 1993. Overproduction, purification and characterization of the bacterioferritin of Escherichia coli and a C-terminally extended variant. Eur. J. Biochem. 213:329–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Antelmann H, et al. 1997. Expression of a stress- and starvation-induced dps/pexB-homologous gene is controlled by the alternative sigma factor sigmaB in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 179:7251–7256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. 2001. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:10037–10041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ball V, Ramsden JJ. 1998. Buffer dependence of refractive index increments of protein solutions Biopolymers 47:489–492 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bhattacharyya G, Grove A. 2007. The N-terminal extensions of Deinococcus radiodurans Dps-1 mediate DNA major groove interactions as well as assembly of the dodecamer. J. Biol. Chem. 282:11921–11930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carrondo MA. 2003. Ferritins, iron uptake and storage from the bacterioferritin viewpoint. EMBO J. 22:1959–1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ceci P, et al. 2004. DNA condensation and self-aggregation of Escherichia coli Dps are coupled phenomena related to the properties of the N-terminus. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:5935–5944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ceci P, Forte E, Di Cecca G, Fornara M, Chiancone E. 2011. The characterization of Thermotoga maritima ferritin reveals an unusual subunit dissociation behavior and efficient DNA protection from iron-mediated oxidative stress. Extremophiles 15:431–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ceci P, Ilari A, Falvo E, Chiancone E. 2003. The Dps protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens does not bind to DNA but protects it toward oxidative cleavage: X-ray crystal structure, iron binding, and hydroxyl-radical scavenging properties. J. Biol. Chem. 278:20319–20326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ceci P, Ilari A, Falvo E, Giangiacomo L, Chiancone E. 2005. Reassessment of protein stability, DNA binding, and protection of Mycobacterium smegmatis Dps. J. Biol. Chem. 280:34776–34785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, et al. 2005. Extensive DNA inversions in the B. fragilis genome control variable gene expression. Science 307:1463–1465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen L, Keramati L, Helmann JD. 1995. Coordinate regulation of Bacillus subtilis peroxide stress genes by hydrogen peroxide and metal ions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:8190–8194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen S, Bleam WF, Hickey WJ. 2009. Simultaneous analysis of bacterioferritin gene expression and intracellular iron status in Pseudomonas putida KT2440 by using a rapid dual luciferase reporter assay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:866–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chiancone E. 2008. Dps proteins, an efficient detoxification and DNA protection machinery in the bacterial response to oxidative stress. Rendiconti Lincei 19:261–270 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chiancone E, Ceci P, Ilari A, Ribacchi F, Stefanini S. 2004. Iron and proteins for iron storage and detoxification. Biometals 17:197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chiaraluce R, et al. 2000. The unusual dodecameric ferritin from Listeria innocua dissociates below pH 2.0. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:5733–5741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 1994. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50:760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Crow A, Lawson TL, Lewin A, Moore GR, Le Brun NE. 2009. Structural basis for iron mineralization by bacterioferritin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131:6808–6813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Davis IW, et al. 2007. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:W375–W383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. DeLano WL. 2002. The PyMOL user's manual. http://www.pymol.org DeLano Scientific, Palo Alto, CA [Google Scholar]

- 25. Douglas T, Ripoll DR. 1998. Calculated electrostatic gradients in recombinant human H-chain ferritin. Protein Sci. 7:1083–1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dowds BC. 1994. The oxidative stress response in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 124:255–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Finegold SM, George WL. 1998. Anaerobic infection in humans. Academic Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gauss GH, et al. 2006. Structure of the DPS-like protein from Sulfolobus solfataricus reveals a bacterioferritin-like dimetal binding site within a DPS-like dodecameric assembly. Biochemistry 45:10815–10827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grant RA, Filman DJ, Finkel SE, Kolter R, Hogle JM. 1998. The crystal structure of Dps, a ferritin homolog that binds and protects DNA. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5:294–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grove A, Wilkinson SP. 2005. Differential DNA binding and protection by dimeric and dodecameric forms of the ferritin homolog Dps from Deinococcus radiodurans. J. Mol. Biol. 347:495–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harrison PM, Arosio P. 1996. The ferritins: molecular properties, iron storage function and cellular regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1275:161–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hempstead PD, et al. 1994. Direct observation of the iron binding sites in a ferritin. FEBS Lett. 350:258–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Herren CD, Rocha ER, Smith CJ. 2003. Genetic analysis of an important oxidative stress locus in the anaerobe Bacteroides fragilis. Gene 316:167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jeanmougin F, Thompson JD, Gouy M, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. 1998. Multiple sequence alignment with Clustal x. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23:403–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jogl G, Tao X, Xu Y, Tong L. 2001. COMO: a program for combined molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 57:1127–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Krissinel E, Henrick K. 2004. Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60:2256–2268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lewin A, Moore GR, Le Brun NE. 2005. Formation of protein-coated iron minerals. Dalton Trans., issue 22, p 3597–3610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu HL, et al. 2004. 2.6 Å resolution crystal structure of the bacterioferritin from Azotobacter vinelandii. FEBS Lett. 573:93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu X, Kim K, Leighton T, Theil EC. 2006. Paired Bacillus anthracis Dps (mini-ferritin) have different reactivities with peroxide. J. Biol. Chem. 281:27827–27835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maaty WS, et al. 2009. Something old, something new, something borrowed; how the thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus responds to oxidative stress. PLoS One 4:e6964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Macedo S, et al. 2003. The nature of the di-iron site in the bacterioferritin from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10:285–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marchler-Bauer A, et al. 2009. CDD: specific functional annotation with the Conserved Domain Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D205–D210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Niviere V, Fontecave M. 2004. Discovery of superoxide reductase: an historical perspective. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 9:119–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Otwinowski Z, Minor W. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode, p 307–326 In Carter C, Sweet R. (ed), Macromolecular crystallography, part A, vol 276 Academic Press, New York, NY: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Papinutto E, et al. 2002. Structure of two iron-binding proteins from Bacillus anthracis. J. Biol. Chem. 277:15093–15098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pfaffl MW. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ramsay B, et al. 2006. Dps-like protein from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Inorg. Biochem. 100:1061–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reott MA, Parker AC, Rocha ER, Smith CJ. 2009. Thioredoxins in redox maintenance and survival during oxidative stress of Bacteroides fragilis. J. Bacteriol. 191:3384–3391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rocha ER, Herren CD, Smalley DJ, Smith CJ. 2003. The complex oxidative stress response of Bacteroides fragilis: the role of OxyR in control of gene expression. Anaerobe 9:165–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rocha ER, Owens G, Jr, Smith CJ. 2000. The redox-sensitive transcriptional activator OxyR regulates the peroxide response regulon in the obligate anaerobe Bacteroides fragilis. J. Bacteriol. 182:5059–5069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rocha ER, Smith CJ. 1998. Characterization of a peroxide-resistant mutant of the anaerobic bacterium Bacteroides fragilis. J. Bacteriol. 180:5906–5912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rocha ER, Smith CJ. 2004. Transcriptional regulation of the Bacteroides fragilis ferritin gene (ftnA) by redox stress. Microbiology 150:2125–2134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rocha ER, Tzianabos AO, Smith CJ. 2007. Thioredoxin reductase is essential for thiol/disulfide redox control and oxidative stress survival of the anaerobe Bacteroides fragilis. J. Bacteriol. 189:8015–8023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Roy S, et al. 2004. X-ray analysis of Mycobacterium smegmatis Dps and a comparative study involving other Dps and Dps-like molecules. J. Mol. Biol. 339:1103–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Roy S, et al. 2007. Role of N and C-terminal tails in DNA binding and assembly in Dps: structural studies of Mycobacterium smegmatis Dps deletion mutants. J. Mol. Biol. 370:752–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schaffer AA, et al. 2001. Improving the accuracy of PSI-BLAST protein database searches with composition-based statistics and other refinements. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:2994–3005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Snydman DR, et al. 2007. National survey on the susceptibility of Bacteroides fragilis group: report and analysis of trends in the United States from 1997 to 2004. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1649–1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Snydman DR, et al. 1999. Multicenter study of in vitro susceptibility of the Bacteroides fragilis group, 1995 to 1996, with comparison of resistance trends from 1990 to 1996. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2417–2422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]