Abstract

The disruption of ung, the unique uracil-DNA-glycosylase-encoding gene in Bacillus subtilis, slightly increased the spontaneous mutation frequency to rifampin resistance (Rifr), suggesting that additional repair pathways counteract the mutagenic effects of uracil in this microorganism. An alternative excision repair pathway is involved in this process, as the loss of YwqL, a putative endonuclease V homolog, significantly increased the mutation frequency of the ung null mutant, suggesting that Ung and YwqL both reduce the mutagenic effects of base deamination. Consistent with this notion, sodium bisulfite (SB) increased the Rifr mutation frequency of the single ung and double ung ywqL strains, and the absence of Ung and/or YwqL decreased the ability of B. subtilis to eliminate uracil from DNA. Interestingly, the Rifr mutation frequency of single ung and mutSL (mismatch repair [MMR] system) mutants was dramatically increased in a ung knockout strain that was also deficient in MutSL, suggesting that the MMR pathway also counteracts the mutagenic effects of uracil. Since the mutation frequency of the ung mutSL strain was significantly increased by SB, in addition to Ung, the mutagenic effects promoted by base deamination in growing B. subtilis cells are prevented not only by YwqL but also by MMR. Importantly, in nondividing cells of B. subtilis, the accumulations of mutations in three chromosomal alleles were significantly diminished following the disruption of ung and ywqL. Thus, under conditions of nutritional stress, the processing of deaminated bases in B. subtilis may normally occur in an error-prone manner to promote adaptive mutagenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Three of the four bases usually present in DNA (cytosine, adenine, and guanine) contain an exocyclic amino group. The loss of this group by deamination occurs spontaneously under physiological conditions via a hydrolytic reaction (33, 34, 53) and leads to the production of the highly mutagenic lesions uracil, hypoxanthine, and xanthine, respectively. This process is greatly enhanced by oxygen free radicals and other agents, such as UV radiation, heat, ionizing radiation, nitrous acid, nitric oxide (NO), and sodium bisulfite (SB) (8, 9, 55, 56).

The spontaneous or induced deamination of cytosine creates a promutagenic U/G mispair that results in G·C-to-A·T transitions. Uracil in DNA may also occur through DNA polymerase's incorporation of dUMP instead of dTMP during replication, creating a U/A base pair that is not directly mutagenic but may be cytotoxic (26, 28, 29). The major pathway to remove uracil from DNA is thought to be base excision repair (BER), initiated by uracil-DNA glycosylase (Ung), first discovered in Escherichia coli in 1974 (32). Ung hydrolyzes the N-glycosylic bond between uracil and deoxyribose, leaving an abasic site (AP site) that is further processed by an apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) endonuclease followed by DNA polymerase and DNA ligase (29, 33).

Ung is a ubiquitous enzyme that belongs to family 1 of the uracil-DNA glycosylases (UDGs) (39, 40, 67). UDGs are widely distributed among organisms of all domains of life and are grouped in at least eight families (15). For instance, in addition to Ung, E. coli possesses a UDG family 2 member designated mismatch-specific uracil-DNA glycosylase (Mug) (16). A similar situation is found for the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, whose genome encodes two UDGs belonging to families 1 and 2, respectively (15). The relevant role played by UDGs is clearly manifested in mammals and Archaea, where at least three and four different UDG activities, respectively, have been found for organisms of these kingdoms (15).

Endonuclease V (Endo V) from E. coli, encoded by the nfi gene, was also reported to be involved in an alternative excision pathway eliminating uracil and other deaminated bases from DNA (17, 22, 66). In silico analysis has revealed the existence of orthologs of this enzyme in several bacterial genomes, yeast, Archaea, and thermophilic organisms, and a homolog of this protein has even been identified in mammals (15). Endonuclease V activity is strictly dependent on MgCl2 and does not function as a DNA glycosylase; instead, it catalyzes the incision of the second phosphodiester bond 3′ to the substrate lesion, generating 3′ OH and 5′ phosphate termini (15). The completion of repair following this pathway is not well understood, but for E. coli, it was proposed previously that the exonuclease activity of XthA and the subsequent action of DNA polymerase I and DNA ligase may be involved (15).

The ability of stressed cell populations to acquire mutations that favor cell growth after applying a nonlethal selection pressure has been termed adaptive or stationary-phase mutagenesis (48). This type of mutagenesis has been reported to occur in E. coli and other prokaryotic and eukaryotic models, including Bacillus subtilis (5, 20, 25, 60). It has been shown that repair pathways that process oxidative stress-induced and mismatched DNA lesions are a key factor in generating potentially beneficial DNA alterations in nondividing B. subtilis cells (11, 41, 64).

B. subtilis relies on several repair mechanisms to counteract the adverse effects of intra- and extracellular factors that generate a myriad of insults to DNA (3, 7, 11, 24, 49, 64). DNA repair genes are differentially expressed during growth and/or sporulation, and the physiological roles played by their encoded products have been demonstrated in several cases (45, 47, 50, 62). Analysis of the genome of B. subtilis reveals the presence of a uracil-DNA-glycosylase-encoding gene (ung) that can be classified into family 1 of the UDGs. The biochemical properties of its encoding product were recently reported, showing that it is more active against uracil in single-stranded DNA than in double-stranded DNA and exhibits a greater preference for U/G than U/A mismatches (42). However, this microorganism lacks genes whose products have obvious homology to members of other UDG families. Here we report that the inactivation of the ung gene resulted in a moderate mutator phenotype, suggesting that additional mechanisms are involved in protecting the genome of B. subtilis from the mutagenic effects of uracil and/or other deaminated bases. In agreement with this suggestion, our results showed that in growing B. subtilis cells, Ung in collaboration with Endo V (YwqL) and the mismatch repair system (MutSL) counteracts the mutagenic effects of DNA base deamination. In contrast, in nondividing B. subtilis cells, Ung and YwqL were shown to exert a promutagenic role that may be important for generating adaptive mutations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. The procedures for the transformation and isolation of chromosomal and plasmid DNAs were described previously (4, 10, 51). The growth medium used routinely was Penassay broth (PAB) (antibiotic medium 3; Difco Laboratories, Sparks, MD). When required, chloramphenicol (Cm; 5 μg/ml), erythromycin (Er; 5 μg/ml), kanamycin (Kan; 10 μg/ml), neomycin (Neo; 10 μg/ml), rifampin (Rif; 10 μg/ml), or tetracycline (Tet; 10 μg/ml) was added to the medium. E. coli cultures were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (36) supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml). Liquid cultures were incubated at 37°C with vigorous aeration.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and/or descriptione | Source or referencef |

|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis strains | ||

| 168 | Wild type; trpC2 | Laboratory stock |

| 1A751 | eglSΔ102bglT/bglSΔEVnpraprhi | BGSC |

| YB955 | hisC952 metB5 leuC427 xin-1 SpβSENS | 60 |

| PERM640a | Δung::lacZ Emr | pPERM633→168d |

| PERM454a | Δnfo::neo ΔexoA::tet Neor Tetr | 49 |

| PERM738a | Δung::lacZ Δnfo::neo ΔexoA::tet Emr Neor Tetr | PERM454→PERM640c |

| MPRYB151 | YB955 carrying mutSL::neo | 41 |

| PERM739a | ΔmutSL::neo Neor | MPRYB151→168c |

| PERM737a | Δung::lacZ ΔmutSL::neo Emr Neor | MPRYB151→PERM640c |

| PERM791a | ΔywqL::lacZ Emr | pPERM800→168d |

| PERM793a | Δung::lacZ ΔywqL::lacZ Cmr Emr | pPERM788→PERM791d |

| PERM868a | Δung::lacZ ΔmutSL::neo with a Pspac-mutSL-lacI construct from pMPR002 inserted into the amyE locus; Emr Neor Spcr | pMPR002→PERM737d |

| PERM942a | Δung::lacZ ΔmutSL::neo with a Phs-ung-lacI construct from pPERM924 inserted into the amyE locus; Emr Neor Spcr | pPERM924→PERM737d |

| PERM944a | Δung::lacZ ΔywqL::lacZ with a Phs-ywqL-lacI construct from pPERM925 inserted into the amyE locus; Cmr Emr Spcr | pPERM925→PERM793d |

| PERM1047a | Δung::lacZ ΔywqL::lacZ with a Phs-ung-lacI construct from pPERM924 inserted into the amyE locus; Cmr Emr Spcr | pPERM924→PERM793d |

| PERM956a | Δung::lacZ ΔywqL::lacZ with a Phs-lacI construct inserted into the amyE locus; Cmr Emr Spcr | pdr111 amyE-hyper-SPANK→PERM793d |

| PERM992a | Δung::lacZ ΔmutSL::neo with a Phs-lacI construct inserted into the amyE locus; Emr Neor Spcr | pdr111 amyE-hyper-SPANK→PERM737d |

| PERM1055b | IA751 carrying Δung::lacZ Cmr | pPERM788→1A751d |

| PERM1056b | 1A751 carrying ΔywqL::lacZ Emr | pPERM800→1A751d |

| PERM1057b | 1A751 carrying Δung::lacZ ΔywqL::lacZ Cmr Emr | pPERM800→PERM1055d |

| PERM1028 | YB955 carrying Δung::lacZ ΔywqL::lacZ Cmr Emr | PERM793→YB955c |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMUTIN4 | Integration vector; Ampr Emr | 63 |

| pJF751 | Integration vector; Ampr Cmr | 14 |

| pdr111 amyE-hyper-SPANK | Hyper-SPANK expression vector; Ampr Spcr | 44 |

| pMPR002 | pDG364 containing the Pspac-mutSL-lacI construct; Ampr Cmr | 64 |

| pPERM270 | pDG148 containing the Pspac-cel9-lacI construct; Ampr Kanr | 1 |

| pPERM633 | 561-bp NotI-BamHI fragment (internal region of ORF) of ung cloned into pMUTIN4; Ampr Emr | This study |

| pPERM788 | 312-bp EcoRI-BamHI fragment (internal region of ORF) of ung cloned into pJF751; Ampr Cmr | This study |

| pPERM800 | 375-bp EcoRI-BamHI fragment (internal region of ORF) of ywqL cloned into pMUTIN4; Ampr Emr | This study |

| pPERM924 | 904-bp B. subtilis ung open reading frame cloned into the SalI-NheI sites of pdr111 amyE-hyper-SPANK; Ampr Spcr | This study |

| pPERM925 | 943-bp B. subtilis ywqL open reading frame cloned into the HindIII-SphI sites of pdr111 amyE-hyper-SPANK; Ampr Spcr | This study |

The background for this strain is 168.

The background for this strain is IA751.

Chromosomal DNA from the strain to left of the arrow was used to transform the strain to the right of the arrow.

DNA of the plasmid to the left of the arrow was used to transform the strain to the right of the arrow.

Amp, ampicillin; Cm, chloramphenicol; Er, erythromycin; Kan, kanamycin; Neo, neomycin; Spc, spectinomycin; Tet, tetracycline.

BGSC, Bacillus Genetic Stock Center.

Construction of mutant strains and integration of ung-lacZ and ywqL-lacZ fusions.

The construction of ung and ywqL mutant strains and transcriptional ung-lacZ and ywqL-lacZ fusions was performed with the integrative vector pMUTIN4 (63). To this end, a 561-bp NotI-BamHI internal fragment of the ung gene (from bp 99 to 660 downstream of the ung translational start codon) and a 375-bp EcoRI-BamHI internal fragment of the ywqL gene (from bp 154 to 529 downstream of the ywqL translational start codon) were amplified by PCR with Vent DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) using chromosomal DNA from B. subtilis 168 (a gift from Wayne Nicholson). The oligonucleotide primers used for the amplification of the ung fragment were 5′-GGCGCGGCCGCGGAGCAAACGATTTATCG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCGGGATCCAATCAATCGGCGCCTC-3′ (reverse), and those used for the amplification of the ywqL fragment were 5′-CCGAATTCCAGGATGGAGAACCATACGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCGGATCCGTCCATATACCTCGCCGTC-3′ (reverse) (restriction sites are underlined). The ung and ywqL PCR fragments were inserted between the NotI and BamHI and the EcoRI and BamHI sites of pMUTIN4, respectively. The resulting constructs, designated pPERM633 (ung::lacZ) and pPERM800 (ywqL::lacZ), were propagated in E. coli DH5α cells. Plasmids pPERM633 and pPERM800 were independently used to transform B. subtilis 168, generating strains PERM640 (ung-lacZ Err) and PERM791 (ywqL-lacZ Err), respectively (Table 1). To obtain a ung ywqL double mutant, a 312-bp EcoRI-BamHI internal fragment of the ung gene (from bp 100 to 396 downstream of the ung translational start codon) was amplified by PCR with Vent DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) using chromosomal DNA from B. subtilis 168 and oligonucleotide primers 5′-GCGAATTCGCGGAGCAAACGATTTATCCG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCGGATCCCTGTCCGCGCCTTACTGTCAG-3′ (reverse) (restriction sites are underlined). The PCR ung fragment was inserted into pJF751 (14) digested with EcoRI and BamHI. The resulting construct, pPERM788, was propagated in E. coli DH5α cells and was used to transform B. subtilis strain PERM791 (ΔywqL Err), generating strain B. subtilis PERM793 (Δung ywqL Cmr Err). Strains deficient in MutSL (mismatch repair [MMR]) were generated by transforming B. subtilis strains 168 (wild type [WT]) and PERM640 (Δung Err) with chromosomal DNA isolated from B. subtilis MPRYB151 (ΔmutSL Neor) (41), generating strains PERM739 (ΔmutSL Neor) and PERM737 (Δung mutSL Err Neor), respectively. The nfo and exoA genes of B. subtilis PERM640 (Δung Err) were interrupted by the transformation of this strain with chromosomal DNA isolated from strains PERM454 (Δnfo exoA Neor Tetr); this procedure generated strain PERM738 (Δung nfo exoA Err Neor Tetr).

To assay DNA base deamination repair in vivo, the ywqL and ung mutations were transferred into B. subtilis 1A751 (eglSΔ102 bglT/bglSΔEV npr apr his), a strain deficient in the production of extracellular cellulase and protease activities (Bacillus Genetic Stock Center, Columbus, OH). To accomplish this, competent cells of B. subtilis 1A751 were independently transformed with plasmids pPERM788 and pPERM800, generating strains PERM1055 (Δung Cmr) and PERM1056 (ΔywqL Err), respectively. To construct the ung ywqL double mutant in the same genetic background, plasmid pPERM800 was used to transform competent cells of B. subtilis PERM1055, generating strain PERM1057 (Δung ywqL Cmr Err) (Table 1).

To carry out stationary-phase-associated-mutagenesis assays, the ung and ywqL mutations were transferred into B. subtilis strain YB955 (a prophage-“cured” strain that carries the hisC952, metB5, and leuC427 alleles) (60). Strain YB955 was transformed with genomic DNA isolated from B. subtilis PERM793 (Δung ywqL), generating strain PERM1028 (Table 1). For all the strains generated, the single or double recombination events leading to the inactivation of the appropriate genes were confirmed by PCR using specific oligonucleotide primers (data not shown).

Constructs to overexpress ung, ywqL, and the mutSL operon.

To overexpress ung or ywqL in the ung ywqL and ung mutSL genetic backgrounds, the open reading frames (ORFs) of the ung and ywqL genes were amplified by PCR with Vent DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) using chromosomal DNA from B. subtilis 168 and oligonucleotide primers 5′-GCGTCGACGTTCGTAAGGAGGCCTGAATC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGGCTAGCTATTTGCCATTCGGCGGCGTC-3′ (reverse) for the ung gene and 5′-GCAAGCTTGGTCGAGAGTGAGCAATCGTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCGCATGCGAACTCAATTGGCAGAGCGAT-3′ (reverse) for the ywqL gene (restriction sites are underlined). The ORFs of ung (905 bp) and ywqL (943 bp) were cloned between the SalI-NheI and HindIII-SphI sites, respectively, of pdr111-amyE-hyper-SPANK (a gift from David Rudner, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA), placing the genes under the control of the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible Phs promoter, generating plasmids pPERM924 (Phs-ung-lacI) and pPERM925 (Phs-ywqL-lacI). A construct termed pMPR002 (Pspac-mutSL-lacI) that overexpresses mutSL from the IPTG-inducible Pspac promoter was previously described (64). Plasmids pPERM924 and pPERM925 were introduced by transformation into B. subtilis strain PERM793 (Δung ywqL), generating strains PERM1047 and PERM944, respectively (Table 1). Plasmids pPERM924 and pMPR002 (Pspac-mutSL-lacI) were independently transformed into competent cells of B. subtilis PERM737 (Δung mutSL) to generate strains PERM942 and PERM868, respectively (Table 1).

β-Galactosidase assays.

Strains PERM640 (ung-lacZ) and PERM791 (ywqL-lacZ) were grown in liquid PAB medium. Samples of 1 ml were collected every 30 min until 4 h after the cessation of exponential growth and washed with 0.025 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), and the cell pellet was stored at −20°C. Cell extracts were obtained by disruption with lysozyme followed by centrifugation, and the β-galactosidase activity in the supernatant fluid was determined according to a previously described protocol, using ortho-nitro-phenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) as a substrate (35, 38). The basal values of the ONPGase activity expressed by the parental strain during the logarithmic and stationary phases of growth were subtracted from the β-galactosidase values of the ywqL-lacZ- and ung-lacZ-containing strains at each time point.

RT-PCR experiments.

Total RNA from exponentially growing or stationary-phase B. subtilis 168 cells grown in PAB medium was isolated by using Tri reagent (RNA/DNA/Protein Isolation reagent; Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH). Reverse transcription-PCRs (RT-PCRs) were performed with the RNA samples and the Master AMP RT-PCR kit (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, WI) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. The primers used for RT-PCR were 5′-GGCGCGGCCGCGGAGCAAACGATTTATCG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCGGGATCCAATCAATCGGCGCCTC-3′ (reverse), which amplified a 561-bp ung fragment encompassing bp 99 to 660 downstream of the ung translational start codon. The primers used to generate a 375-bp RT-PCR product of ywqL encompassing bp 154 to 529 downstream of the ywqL translational start codon were 5′-CCGAATTCCAGGATGGAGAACCATACGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCGGATCCGTCCATATACCTCGCCGTC-3′ (reverse). The absence of chromosomal DNA in the RNA samples was assessed by PCRs carried out with Vent DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) and the set of primers described above. The size of the RT-PCR product was assessed with reference to the migration of a 1-kbp Plus DNA ladder (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) during agarose gel electrophoresis.

Analysis of spontaneous mutation frequencies.

Spontaneous mutations to rifampin resistance (Rifr) in cultures were determined as follows. Strains were grown for 24 h at 37°C in PAB medium supplemented with the proper antibiotics, and aliquots of cells were plated onto six LB plates containing 10 μg/ml rifampin. Rifr colonies were counted after 2 days of incubation at 37°C. The number of cells used to calculate the frequency of mutation to Rifr was determined by plating aliquots of appropriate dilutions onto LB medium plates without rifampin and incubating the plates for 24 h at 37°C. Selection medium for strains overexpressing ung, ywqL, or mutSL was supplemented with 2 mM IPTG. Mutation frequencies are reported as the average numbers of Rifr colonies per 109 viable cells, and all these experiments were repeated at least three times.

Analysis of mutagenesis induced by SB.

Mutations to Rifr in B. subtilis cells treated with agents that promote the deamination of bases in DNA were determined as follows. To determine the mutagenesis generated by SB, PAB cultures of each strain grown overnight were inoculated into flasks containing fresh PAB medium to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5, each culture was divided in half, and the two halves were transferred into different flasks. One of the cultures was untreated, and the other was treated with 0.25 mM SB. The flasks of untreated and SB-treated cultures were shaken at 37°C for 12 h. Mutation frequencies were determined by plating aliquots of each culture onto six LB plates containing 10 μg/ml rifampin as well as plating aliquots of appropriate dilutions onto LB plates without rifampin. Rifr colonies were counted after 24 h of incubation at 37°C.

DNA base deamination repair assay.

Assays of the repair of deaminated DNA bases in vivo were performed as follows. Plasmid pPERM270 containing an IPTG-inducible spac-cel9 construct (Pspac-cel9) (1, 46, 61) was mutagenized, as previously described (12), by dilution 10-fold into 4 M NaHSO3-40 mM mercaptoethanol (pH 5.8) and incubation at 37°C for 120 min. The treated plasmid was dialyzed at 4°C against 2,000 volumes of 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0)–20 mM MgSO4-1 mM mercaptoethanol for 24 h with three buffer changes. The isogenic strains B. subtilis 1A751, B. subtilis PERM1055 (Δung), B. subtilis PERM1056 (ΔywqL), and B. subtilis PERM1057 (Δung ywqL) were transformed to Kanr with either SB-treated or untreated pPERM270, and transformants were screened by using Congo red for the production of cellulase activity as previously described (6, 18). In brief, the transformed colonies were grown at 37°C on LB agar plates supplemented with Kan, 0.2% carboxymethyl-cellulose (CMC) as a substrate, and 5 mM IPTG. The presence of cellulolytic activity was indicated by the formation of a clear zone on the agar plate after staining with 0.2% Congo red for 10 min and two destaining washes with 0.5 M NaCl. The DNA repair activities of the different strains were determined by calculating the mutation frequency as the number of colonies that lost the ability to produce cellulase activity among the total Kanr colonies.

Stationary-phase mutagenesis assays.

The stationary-phase mutagenesis assays were performed as previously described (41, 60). Briefly, 10 ml of cells was grown with vigorous aeration in PAB medium at 37°C to 90 min after the cessation of exponential growth (designated T90). Cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature and then resuspended in 10 ml of Spizizen minimal salts (SMS). One hundred microliters of cells was plated in sextuplicates onto solid Spizizen minimal medium (SMM) (58) (1× Spizizen salts supplemented with 0.5% glucose and either 50 μg or 200 ng of the required amino acid/ml and 50 μg each of isoleucine and glutamic acid/ml). The concentration of the amino acid used depended on the reversion that was being selected. For instance, when selecting for His+ revertants, 50 μg of methionine and leucine/ml was added to the medium, and 200 ng of histidine/ml was added. Isoleucine and glutamic acid were added as described previously (59), in order to maintain the viability of the cells. The number of revertants was scored daily. The initial number of bacteria plated for each experiment was determined by the serial dilution of the bacterial cultures and plating of the cells onto LB plates. The number of colonies was then determined following 48 h of growth at 37°C. These experiments were repeated at least three times.

The survival rates of the bacteria plated onto the minimal selective medium were determined as follows. Three agar plugs were removed from each selection plate every 2 days. The plugs were removed with sterile Pasteur pipettes and taken from areas of the plates where no growth was observed. The plugs were suspended in 1 ml of 1× Spizizen salts, diluted, and plated onto LB plates. Again, the number of colonies was determined following 48 h of growth at 37°C.

The growth-dependent reversion rates for His+, Met+, and Leu+ revertants were measured by fluctuation tests with the Lea-Coulson formula, r/m − ln(m) = 1.24 (31). Three parallel cultures were used to determine the total number of CFU plated onto each plate (Nt) by titration. The mutation rates were calculated as previously described, with the formula m/2Nt (41, 60).

Statistical analyses.

Statistical tests were performed by using Statistica 8 for Windows (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK). Wilcoxon tests were performed during the analysis of mutagenesis induced by SB. For analyses of spontaneous mutation frequencies, a generalized model (GLM) was carried out, employing a Poisson distribution of data and long-link function. When we had unequal n's between treatments, we used the likelihood type 3 test in the model, and we used likelihood type 1 for equal n's between treatments. Differences with P values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Spontaneous mutation rates in a B. subtilis ung null mutant.

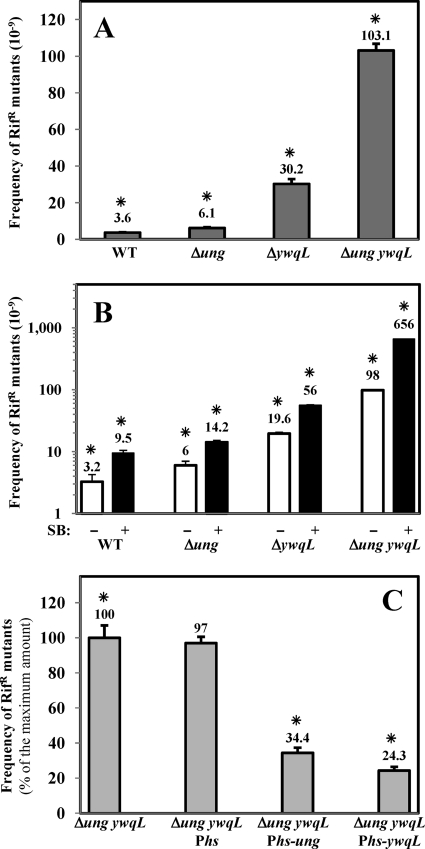

The deamination of cytosine occurs spontaneously in cells generating U/G promutagenic mispairs that are processed by the BER pathway with the aid of uracil-DNA glycosylases. The genome of B. subtilis contains only a single uracil-DNA-glycosylase-encoding gene, termed ung. Therefore, it was expected that a ung disruption should induce a strong mutator phenotype in this microorganism. Surprisingly, in comparison with the wild-type parental strain, the loss of ung function increased the spontaneous mutation frequency to Rifr by only ∼2-fold (Fig. 1A). As expected, the mutation frequency of the Ung-deficient strain was significantly increased by SB treatment (Fig. 1B). In addition, a modest increase (∼2.5-fold) in the Rifr mutation frequency was observed when null mutations in nfo and exoA, encoding the major AP endonucleases in B. subtilis (50, 57), were introduced into the Δung genetic background (data not shown). Therefore, we investigated whether, in addition to the BER pathway that employs Ung, B. subtilis has additional mechanisms to contend with the mutagenic effects of uracil and other deaminated bases.

Fig 1.

Frequencies of spontaneous mutation to Rifr of different B. subtilis strains. (A) B. subtilis strains 168 (parental strain), PERM640 (Δung), PERM791 (ΔywqL), and PERM793 (Δung ywqL) were grown overnight in PAB medium, and frequencies of mutation to Rifr were determined as described in Materials and Methods. A GLM revealed significant differences between compared values (χ2 = 1,997.549; df = 3; P < 0.0001). (B) Frequencies of mutation to Rifr of different B. subtilis strains treated with SB. B. subtilis strains 168 (parental strain), PERM640 (Δung), PERM791 (ΔywqL), and PERM793 (Δung ywqL) were grown at 37°C in PAB medium to an OD600 of 0.5 and then divided into two Erlenmeyer flasks; one of the flasks was left as an untreated control (white bars), and the other was supplemented with 0.25 mM SB (black bars). Cultures were shaken for 12 additional hours at 37°C, and frequencies of mutation to Rifr were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as averages ± standard deviations (SD) from at least two independent experiments. Mutation frequencies of untreated and SB-treated strains were compared with a Wilcoxon test, revealing significant differences (P < 0.027). (C) Effects of ung or ywqL overexpression on the frequency of spontaneous mutation to Rifr of a Δung ywqL strain. B. subtilis strains PERM793 (Δung ywqL), PERM956 (Δung ywqL Phs), PERM1047 (Δung ywqL Phs-ung), and PERM944 (Δung ywqL Phs-ywqL) were grown overnight at 37°C in PAB medium supplemented with the proper antibiotics and IPTG (2 mM), when required. Frequencies of mutation to Rifr were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as percentages of the maximum value calculated for the Δung ywqL strain. Values are expressed as averages ± standard deviations from at least two independent experiments. A GLM revealed significant differences between compared values (χ2 = 240.3844; df = 3; P < 0.0001). Asterisks indicate values that were significantly different.

Antimutagenic role of YwqL.

Although B. subtilis seems to possess a single UDG, the results of a BLAST analysis revealed the existence of a genomic open reading frame, designated ywqL, that encodes a putative ortholog of endonuclease V (Endo V) of E. coli (30). Amino acid sequence analysis revealed that YwqL is 31% identical and 51% homologous to E. coli Endo V, encoded by the nfi gene (data not shown). The product of nfi has been associated with the processing of a wide spectrum of DNA lesions and structures, including uracil, hypoxanthine, xanthine, base mismatches, AP sites, hairpins, unpaired loops, and pseudo-Y and flap structures (17, 22, 65, 66).

To investigate the contribution of YwqL to DNA repair in B. subtilis, a null ywqL mutant was generated and used to study the prevention of deamination-induced DNA damage. The frequencies of spontaneous mutation to Rifr in the ywqL strain were ∼8-fold higher than those in the YwqL-proficient strain; this response was significantly exacerbated in the YwqL-deficient strain by SB treatment (Fig. 1A and B). Together, these results strongly suggest that in addition to Ung, B. subtilis YwqL prevents mutagenic effects of cytosine (and perhaps guanine and adenine) deamination through the so-called alternative excision repair pathway (15, 27).

Base-deamination-induced mutagenesis is enhanced in a Ung YwqL-deficient B. subtilis strain.

Instead of relying on additional UDGs, B. subtilis uses Ung and YwqL to prevent the genotoxic effects of base deamination. To investigate whether both proteins operate on the same type of lesions, a ung ywqL strain was constructed. Notably, the mutation frequencies expressed by strains with single defects in ung and ywqL were significantly lower than those exhibited by the strain with defects in both genes, as the mutation frequency of this strain was ∼3-fold higher than the additive values of the single ung or ywqL strain (Fig. 1A and B). These results suggest that Ung and YwqL counteract the mutagenic effects of the base analog uracil. Two experimental approaches were undertaken in attempts to further support this suggestion. First, the ung ywqL strain was treated with the base deamination inducer SB, and the effects of this agent on mutation frequencies were determined (9, 21, 54). With respect to a control culture, SB increased the mutation frequency of the ung ywqL strain ∼6-fold (Fig. 1B). Significantly, the effect of SB in the ung ywqL mutant was several times greater than that observed for strains harboring single ung or ywqL mutations (Fig. 1B). We also generated constructs to overexpress ung or ywqL from the IPTG-inducible Phs promoter. These constructs were used to recombine single copies of the Phs-ung and Phs-ywqL cassettes into the amyE locus of the ung ywqL strain. Consistent with their suggested antimutagenic roles, the overexpression of either Ung or YwqL from the Phs promoter significantly decreased the mutation frequency of the ung ywqL strain, while the Phs vector alone did not (Fig. 1C).

Strains lacking Ung and/or YwqL are also deficient in repair of deaminated DNA.

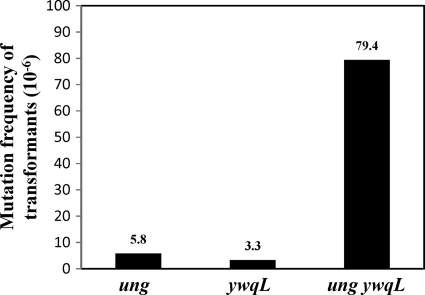

The strains that lacked Ung and/or YwqL exhibited increased frequencies of mutation to Rifr. Therefore, we investigated whether the mutagenic phenotypes exhibited by these strains were correlated with a deficiency in the repair of deaminated DNA in vivo. We treated in vitro plasmid preparations of pPERM270, which can direct the synthesis of an extracellular cellulase in B. subtilis in an IPTG-dependent manner (1, 46), with the deamination inducer SB (21, 54). Both the treated and untreated plasmids were transformed into cellulase-deficient B. subtilis 1A751 (eglSΔ102 bglT/bglSΔEV npr aprE his) lacking Ung and/or YwqL. Deficiencies in the repair of deaminated bases in the different strains were then determined by calculating the mutation frequency from the number of colonies that had no cellulase activity among the total Kanr colonies. As shown in Fig. 2, the absence of Ung or YwqL decreased the capability of B. subtilis to process deaminated DNA, and the absence of both repair proteins increased this effect even further. In contrast, no deficiencies in the processing of the deaminated plasmid were found for the Ung YwqL-proficient strain (data not shown). From these results, we conclude that the increased Rifr mutagenesis in strains lacking Ung and/or YwqL is due to deficiencies in the repair of uracil and presumably other deaminated bases in DNA.

Fig 2.

Abilities of different B. subtilis strains to repair a deaminated Pspac-cel9 expression plasmid. Competent cells of B. subtilis strains 1A751 (parental strain), PERM1055 (Δung), PERM1056 (ΔywqL), and PERM1057 (Δung ywqL) were transformed with a Pspac-cel9 construct treated or not with SB as described in Materials and Methods. Around 300 Kanr colonies of each strain were tested for the ability to produce cellulase activity in situ, as previously described (6, 18). The DNA repair activity is expressed as the mutation frequency of transformant colonies that lost the ability to produce cellulase activity among the total Kanr colonies analyzed.

Analysis of ung and ywqL expression during B. subtilis growth.

As noted above, Ung and YwqL may both act to prevent the genotoxic effects of uracil. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that ung and ywqL will exhibit similar patterns of expression. To investigate this notion, we utilized B. subtilis strains PERM640 and PERM791, which harbor single copies of transcriptional ung-lacZ and ywqL-lacZ fusions, respectively. To avoid sporulation, the temporal patterns of expression of both lacZ fusions in PAB medium were analyzed. Under these conditions, ywqL-directed β-galactosidase activity was detected in exponentially growing cells, and levels remained constant during the transition from the exponential to the stationary phase and until at least 4.5 h beyond the latter point (Fig. 3A). Under the same conditions, the ung-lacZ transcriptional fusion showed a similar pattern of expression (Fig. 3B).

Fig 3.

(A and B) Levels of β-galactosidase from B. subtilis strains containing ung-lacZ (A) or ywqL-lacZ (B) transcriptional fusions. B. subtilis strains PERM640 and PERM791 were independently grown at 37°C in PAB medium. Cell samples were collected at the indicated times and treated with lysozyme, and the extracts were assayed for β-galactosidase activity as described in Materials and Methods. Shown are averages of data from triplicate independent experiments ± SD of the β-galactosidase specific activity (■) and A600 (●). (CI and II) RT-PCR analysis of ung (I) and ywqL (II) transcription during vegetative and stationary phases of growth. RNA samples (∼1 μg) isolated from a B. subtilis 168 PAB culture, at the times indicated, were processed for RT-PCR analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Arrowheads show the sizes of the expected RT-PCR products. (III) 16S and 23S rRNA bands. T0 is the time point for the culture when the slopes of the logarithmic and stationary phases of growth intercepted. T2 and T4 indicate the times in hours after T0. Veg, vegetative growth.

To further show that ywqL and ung exhibited similar patterns of gene expression, total RNA samples isolated from different stages of the B. subtilis life cycle were analyzed by qualitative RT-PCR to detect the mRNAs of these two genes. As shown in Fig. 3C, the temporal patterns of expression exhibited by the ung- and ywqL-lacZ fusions were paralleled by the RT-PCR results, since mRNAs of both ywqL and ung were detected not only in exponentially growing cells but also during the transition and stationary phases of growth.

Ung and MutSL counteract the mutagenic effects of base deamination.

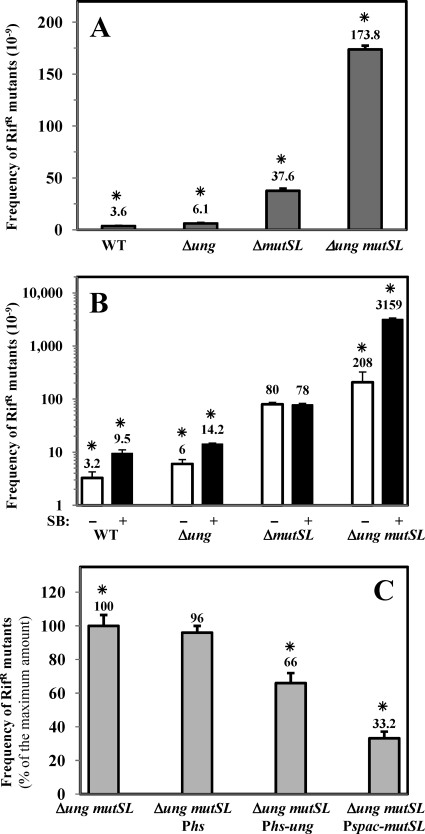

Previous studies also implicated the mismatch repair (MMR) pathway in the processing of U/G mispairs in mammals (52). To investigate if this DNA repair pathway also contributes to the prevention of the mutagenic effects of uracil on B. subtilis DNA, a null mutSL mutation was recombined into the genome of the ung strain to generate a ung mutSL strain, and the mutation frequency of these strains was determined (Fig. 4A). The spontaneous mutation frequency of the ung mutSL strain was ∼4-fold higher than the sum of the frequencies for the single mutant strains. These results suggest that in addition to Ung, the MMR pathway also prevents the mutagenic effects of base deamination. In support of the latter contention, a dramatic increase in the mutation frequency of the ung mutSL strain was observed following its treatment with SB (Fig. 4B), an agent that preferentially promotes cytosine deamination (21, 54). To further investigate the contribution of Ung and MutSL to counteracting the mutagenic effects observed for the ung mutSL strain, we independently inserted Phs-ung or Pspac-mutSL cassettes into the amyE locus of the ung mutSL strain. The IPTG induction of either ung or mutSL from the Phs or Pspac promoter, respectively, partially complemented the mutagenic phenotype of the ung mutSL strain, although a higher level of complementation was obtained with the Pspac-mutSL cassette (Fig. 4C). Together, these results suggest that U/G promutagenic mispairs not only are subject to Ung processing but also are corrected with the participation of the MMR pathway.

Fig 4.

(A) Frequencies of spontaneous mutation to Rifr of different B. subtilis strains. B. subtilis strains 168 (parental strain), PERM640 (Δung), PERM739 (ΔmutSL), and PERM737 (Δung mutSL) were grown overnight in PAB medium, and frequencies of mutation to Rifr were determined as described in Materials and Methods. A GLM revealed significant differences between compared values (χ2 = 3,791.829; df = 3; P < 0.0001). (B) Frequencies of mutation to Rifr of different B. subtilis strains treated with SB. B. subtilis strains 168 (parental strain), PERM640 (Δung), PERM739 (ΔmutSL), and PERM737 (Δung mutSL) were grown at 37°C in PAB medium to an OD600 of 0.5 and then divided into two flasks, one left as an untreated control (white bars) and the other supplemented with 0.25 mM SB (black bars). Cultures were shaken for 12 additional hours at 37°C, and frequencies of mutation to Rifr were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as averages ± standard deviations from at least two independent experiments. Except for the ΔmutSL strain, a Wilcoxon test revealed significant differences (P < 0.027) between mutation frequencies of untreated and SB-treated strains. (C) Effects of ung or mutSL overexpression on the frequency of spontaneous mutation to Rifr of a Δung mutSL strain. B. subtilis strains PERM737 (Δung mutSL), PERM992 (Δung mutSL Phs), PERM942 (Δung mutSL Phs-ung), and PERM868 (Δung mutSL Pspac mutSL) were grown overnight at 37°C in PAB medium supplemented with the proper antibiotics and IPTG (2 mM), when required. Frequencies of mutation to Rifr were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as percentages of the maximum value calculated for the Δung mutSL strain. Values are expressed as averages ± standard deviations from at least two independent experiments. A GLM revealed significant differences between compared values (χ2 = 1,120.381; df = 3; P < 0.0001). Asterisks indicate values that were significantly different.

Adaptive mutagenesis in B. subtilis cells lacking Ung and YwqL.

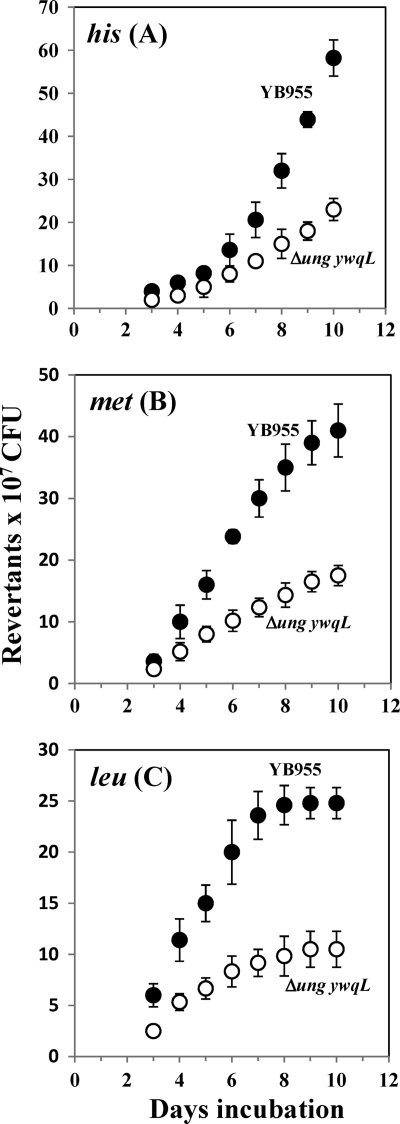

As demonstrated in this work, Ung, YwqL, and MMR are all involved in protecting the genome of growing B. subtilis cells from the mutagenic effects induced by DNA base deamination. However, as noted above, ung and ywqL exhibited high levels of expression during the stationary phase of growth as well, suggesting that their protein products may protect cells from base-deamination-induced mutagenesis under conditions of no actual growth. To test this idea, the ung and ywqL mutations were transferred into B. subtilis strain YB955, a model system widely employed to understand how mutations are generated in amino-acid-starved cells (11, 41, 60, 64). This strain is auxotrophic for three amino acids due to the mutations hisC952 (amber), metB5 (ochre), and leuC427 (missense) (60). Surprisingly, the results of the stationary-phase-associated experiments revealed that with respect to parental strain YB955, there was a significant reduction in the number of His+, Met+, and Leu+ revertants generated by the Ung YwqL-deficient strain (Fig. 5). Thus, with respect to the parental strain, during day 8, the level of production of revertants in the three alleles tested was around three times lower for the ung ywqL mutant (Fig. 5). Importantly, during the course of the experiment, there were no significant differences in the survival rates of the two strains (data not shown). Thus, the decrease in the number of His+, Met+, and Leu+ revertant colonies observed for the ung ywqL strain was not due to differences in growth or survival with respect to the parental strain. The growth-dependent mutation rates of the ung ywqL strain for the generation of His+, Met+, and Leu+ colonies were also determined and compared with those of parental strain YB955. The results revealed that in exponentially growing cells, the his, met, and leu reversion rates were not significantly different between the Ung YwqL-deficient strain and parental strain YB955 (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that the processing of uracil and perhaps other deaminated bases in nondividing B. subtilis cells takes place in an error-prone manner and further suggest that Ung and/or YwqL is involved in determining the error frequency of this process.

Fig 5.

Stationary-phase-induced reversions for the his (A), met (B), and leu (C) mutant alleles of B. subtilis strains YB955 (●) and PERM1028 (Δung ywqL) (■), as described in Materials and Methods. Results are the average numbers of accumulated revertants in six different selection plates. This experiment was performed at least three times.

DISCUSSION

E. coli and other organisms rely on redundant UDGs to counteract the mutagenic effects of uracil generated from cytosine deamination (16, 23, 37, 39). The disruption of ung in E. coli increases spontaneous Rifr mutations ∼5-fold (13), although a UDG (Mug) can compensate for the loss of the Ung function in this microorganism to some degree. In contrast, a previously reported analysis of the B. subtilis genome revealed the existence of a single open reading frame encoding a uracil-DNA glycosylase termed ung (30). Unexpectedly, the disruption of this gene increased the spontaneous Rifr mutation frequency of B. subtilis cells only 1.7-fold, although this effect was enhanced by the uracil inducer SB. These results suggest that the BER pathway that employs Ung plays a minor role in eliminating uracils that are spontaneously generated in the B. subtilis genome. As noted above, the B. subtilis genome lacks additional UDG-encoding genes; therefore, we speculated that alternative DNA repair proteins that may recognize a broader spectrum of DNA lesions could participate in counteracting the mutagenic effects of base deamination in B. subtilis. This appears to be the case, as the disruption of ywqL, which encodes a putative endonuclease V (30), induced a stronger Rifr phenotype, increasing its mutation frequency ∼8-fold in comparison with that of the parental strain. It was reported previously that Endo V works as a promiscuous enzyme in E. coli, as in addition to processing uracils, it is also involved in the repair of hypoxanthine, xanthine, and AP sites, among other types of lesions (17, 22, 65, 66). Our results suggest that YwqL plays a similar role in B. subtilis, as the mutation frequency of a ywqL strain was enhanced by the base deamination promoter SB. Thus, the higher level of Rifr mutagenesis exhibited by the ΔywqL mutant than that exhibited by the Δung strain is in agreement with its promiscuous ability to process several types of DNA damage, in addition to U/G mispairs.

Interestingly, in reference to the single ung and ywqL strains, a significant increase in the spontaneous mutation frequency of the Ung YwqL-deficient strain was observed, confirming that both proteins contend with the mutagenic effects of DNA base deamination. The results supporting this notion were that SB, which primarily induces cytosine deamination, significantly increased the mutation frequency of the ung ywqL strain. In addition, the ability to repair uracils in vivo that were generated by SB in a plasmid in vitro was significantly diminished in the strain that lacked both Ung and YwqL. Together, these results strongly suggest that the repair of uracils in B. subtilis occurs with the participation of both Ung and YwqL. However, YwqL may process not only uracils but also other types of DNA lesions, including AP sites. In support of this notion, our results showed that the Rifr phenotype exhibited by the ung ywqL strain was complemented not only by the overexpression of ung but also by the increase of the transcription of ywqL in this genetic background. Therefore, the specificity of Ung to repair uracils and the ability of YwqL to process a wider spectrum of DNA lesions, including deaminated bases, may explain the partial complementation generated by the Phs-ung and Phs-ywqL cassettes. As the elimination of uracils from DNA with the participation of Ung proceeds through the BER pathway, it remains to be investigated how YwqL processes uracil and other deaminated bases through this alternative excision repair pathway (27). As previously shown (15), Endo V catalyzes the rupture of the second phosphodiester bond 3′ to the damaged base; however, the factors that complete this repair process are poorly understood. For instance, the 3′→5′ exonuclease activities of Xth and DNA polymerase I in E. coli and AP endonuclease I (APEX I) together with a 3′ flap endonuclease in mammals have been implicated in postincisional events (15).

It was reported previously that the Msh2/Msh6 heterodimer (MutSα) is able to recognize U/G mispairs (52), although this type of lesion may not be processed by the MMR machinery in human cells (52). However, analyses of Rifr mutation frequencies in ung, mutSL, and ung mutSL strains suggested that MMR and Ung are both involved in the processing of uracils. Therefore, in contrast to mammals, the MMR system of B. subtilis seems to be involved in the repair of U/G mispairs; this idea was supported by the increase in the mutation frequency of the Ung MMR-deficient strain by SB and the complementation of the Rifr phenotype of this strain by the overexpression of either ung or mutSL.

The ability of the MMR system to interact with components of the BER pathway has been demonstrated to occur in human cells as well as in bacteria (2, 43). For instance, the interference between Ung and MMR during the processing of adjacent U/G mispairs was proposed previously to control somatic hypermutation (SHM) in lymphocytes (52). Similarly, a physical interaction between MutS and MutY was demonstrated to occur in E. coli and human cells (2, 19). The possibility of a physical interaction between Ung and MutS that may regulate the antimutagenic activity of both pathways is under investigation in our laboratory.

The results described in this work revealed that in growing B. subtilis cells, the action of not only Ung but also YwqL minimizes the mutagenic effects of base deamination. Consistent with this idea, our results revealed that ung and ywqL are expressed during the exponential growth of this bacterium. However, both genes maintained high levels of expression during stationary phase. Therefore, we investigated the impact of base deamination in stationary-phase-associated mutagenesis by utilizing B. subtilis strain YB955 (hisC952 metB5 leuC427) deficient in both Ung and YwqL. A significant reduction in the his, met, and leu reversion frequencies was observed for the ung ywqL mutant with respect to the values for the strain containing both Ung and YwqL. These results suggest that the processing of deaminated bases and perhaps other AP sites contributes to adaptive mutagenesis in nutritionally stressed, nondividing B. subtilis cells. However, during growth, the his, met, and leu reversion rates of the ung ywqL mutant did not differ from those calculated for the parental strain, suggesting that another DNA repair system(s) avoids the mutagenic effects of base deamination in this strain. In support of this notion, the results described in this work indicate that the MMR pathway is involved in counteracting the mutagenic effects of uracil. In contrast, in nondividing cells, where a saturation of the MMR system occurs (11, 41, 64), a different situation was found to occur. Therefore, experiments aimed at an understanding of the mechanism(s) involved in the generation reversions in B. subtilis YB955 due to the actions of YwqL and Ung under conditions of no cell growth are currently in progress. The promutagenic effect of Ung and YwqL described in this work is not unprecedented, as it was postulated previously that in pathogen-activated B cells, the repair of uracils occurs in an error-prone manner (52). Moreover, it was recently proposed that in starved B. subtilis cells, the saturation of the MMR system may induce the expression of mutY, disturbing the balance between MutY and MMR proteins to produce adaptive Leu+ revertants (11). An inspection of the B. subtilis genome indicated that ung and ywqL are the distal cistrons of the putative ywdDEF-ung and ywqGHIJKL operons, respectively (30). Therefore, the phenotypic effects exhibited by the single and double ung and ywqL mutants cannot be due to polar effects caused by the integration mutagenesis of these genes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the University of Guanajuato and by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT) (grant 84482) of México. K.L.-O. and M.P.H. were supported by scholarships from the CONACYT.

We are grateful for the excellent technical assistance of Norma Ramírez-Ramírez.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 November 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Avitia CI, et al. 2000. Temporal secretion of a multicellulolytic system in Myxobacter sp. AL-1. Molecular cloning and heterologous expression of cel9 encoding a modular endocellulase clustered in an operon with cel48, an exocellobiohydrolase gene. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:7058–7064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bai H, Lu AL. 2007. Physical and functional interactions between Escherichia coli MutY glycosylase and mismatch repair protein MutS. J. Bacteriol. 189:902–910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barraza-Salas M, et al. 2009. Effects of forespore-specific overexpression of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease Nfo on the DNA-damage resistance properties of Bacillus subtilis spores. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 302:159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boylan RJ, Mendelson NH, Brooks D, Young FE. 1972. Regulation of the bacterial cell wall: analysis of a mutant of Bacillus subtilis defective in biosynthesis of teichoic acid. J. Bacteriol. 110:281–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cairns J, Overbaugh J, Miller S. 1988. The origin of mutants. Nature 335:142–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Castellanos-Juárez FX, Sandoval AA, Urtiz-Estrada N, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2006. Obtención de variantes hiperactivas e inactivas de la endocelulasa Cel9 de Myxobacter sp. AL-1. Acta Univ. 16:22–28 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Castellanos-Juárez FX, et al. 2006. YtkD and MutT protect vegetative cells but not spores of Bacillus subtilis from oxidative stress. J. Bacteriol. 188:2285–2289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen H, Shaw BR. 1993. Kinetics of bisulfite-induced cytosine deamination in single-stranded DNA. Biochemistry 32:3535–3539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chernikov AV, Gudkov SV, Shtarkman IN, Bruskov VI. 2007. Oxygen effect in heat-induced DNA damage. Biophysics 52:185–190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cutting SM, Vander Horn PB. 1990. Genetic analysis, p 27–74 In Harwood CM, Cutting SM. (ed), Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons, Sussex, England [Google Scholar]

- 11. Debora BN, et al. 2011. Mismatch repair modulation of MutY activity drives Bacillus subtilis stationary-phase mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol. 193:236–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duncan BK, Weiss B. 1982. Specific mutator effects of ung (uracil-DNA glycosylase) mutations in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 151:750–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Duncan BK, Rockstroh PA, Warner HR. 1978. Escherichia coli K-12 mutants deficient in uracil-DNA glycosylase. J. Bacteriol. 134:1039–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferrari E, Haward SMH, Hoch JA. 1985. Effect of sporulation mutations on subtilisin expression assayed using a subtilisin-β-galactosidase gene fusion, p 180–184 In Hoch JA, Setlow P. (ed), Molecular biology of microbial differentiation. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 15. Friedberg EC, et al. 2006. DNA repair and mutagenesis, 2nd ed American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gallinari P, Jiricny J. 1996. A new class of uracil-DNA glycosylases related to human thymine-DNA glycosylase. Nature 383:735–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gates FT, Linn S. 1977. Endonuclease V of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 252:1647–1653 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gilkes NR, Langsford ML, Kilburn DG, Miller RC, Warren RAJ. 1984. Mode of action and substrate specificities of cellulases from cloned bacterial genes. J. Biol. Chem. 259:10455–10459 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gu Y, et al. 2002. Human MutY homolog, a DNA glycosylase involved in base excision repair, physically and functionally interacts with mismatch repair proteins human MutS homolog 2/human MutS homolog 6. J. Biol. Chem. 277:11135–11142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Halas A, Baranowska H, Policinska Z. 2002. The influence of the mismatch repair system on stationary-phase mutagenesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 42:140–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hayatsu H, Wataya Y, Kai K, Iida S. 1970. Reaction of sodium bisulfite with uracil, cytosine, and their derivatives. Biochemistry 7:2858–2865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. He B, Qing H, Kow YW. 2000. Deoxyxanthosine in DNA is repaired by Escherichia coli endonuclease V. Mutat. Res. 459:109–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hendrich B, Bird A. 1998. Identification and characterization of a family of mammalian methyl-CpG binding proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:6538–6547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ibarra JR, et al. 2008. Role of the Nfo and ExoA apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases in repair of DNA damage during outgrowth of Bacillus subtilis spores. J. Bacteriol. 190:2031–2038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kasak L, Horak R, Kivisaar M. 1997. Promoter-creating mutations in Pseudomonas putida: a model system for the study of mutation in starving bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:3134–3139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kouzminova EA, Kuzminov A. 2006. Fragmentation of replicating chromosomes triggered by uracil in DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 355:20–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kow YW. 2002. Repair of deaminated bases in DNA. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 33:886–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Krokan HE, Drablos F, Slupphaug G. 2002. Uracil in DNA—occurrence, consequences and repair. Oncogene 21:8935–8948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krokan HE, Standal R, Slupphaug G. 1997. DNA glycosylases in the base excision repair of DNA. Biochem. J. 325:1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kunst F, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the Gram positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390:249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lea DE, Coulson CA. 1949. The distribution of the numbers of mutants in bacterial populations. J. Genet. 49:264–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lindahl T. 1974. An N-glycosidase from Escherichia coli that releases free uracil from DNA containing deaminated cytosine residues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 71:3649–3653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lindahl T. 1979. DNA glycosylases, endonucleases for apurinic/apirimidinic sites and base excision repair. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 22:135–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lindahl T. 1993. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature 362:709–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mason JM, Hackett RH, Setlow P. 1988. Regulation of expression of genes coding for small, acid-soluble proteins of Bacillus subtilis spores: studies using lacZ gene fusions. J. Bacteriol. 170:239–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 37. Neddermann P, Jiricny J. 1994. Efficient removal of uracil from GU mispairs by the mismatch-specific thymine DNA glycosylase from HeLa cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:1642–1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nicholson WL, Setlow P. 1990. Sporulation, germination and outgrowth, p 391–550 In Harwood CR, Cutting SM. (ed), Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons, Sussex, England [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nilsen H, et al. 2001. Excision of deaminated cytosine from the vertebrate genome: role of the SMUG1 uracil-DNA glycosylase. EMBO J. 20:4278–4286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Olsen LC, Aasland R, Krokan HE, Helland DE. 1991. Human uracil-DNA glycosylase complements E. coli ung mutants. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:4473–4478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pedraza-Reyes M, Yasbin RE. 2004. Contribution of the mismatch DNA repair system to the generation of stationary-phase-induced mutants of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 186:6485–6491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pérez-Lago L, et al. 2011. Characterization of Bacillus subtilis uracil-DNA glycosylase and its inhibition by phage ϕ29 protein p56. Mol. Microbiol. 80:1657–1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pitsikas P, Polosina YY, Cupples CG. 2009. Interaction between the mismatch repair and nucleotide excision repair pathways in the prevention of 5-azacytidine-induced CG-to-GC mutations in Escherichia coli. DNA Repair 8:354–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pybus C, et al. 2010. Transcription-associated mutation in Bacillus subtilis cells under stress. J. Bacteriol. 192:3321–3328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ramírez MI, Castellanos FX, Yasbin RE, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2004. The ytkD (mutTA) gene of Bacillus subtilis encodes a functional antimutator 8-oxo-(dGTP/GTP)ase and is under dual control of sigma A and sigma F RNA polymerase. J. Bacteriol. 186:1050–1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ramírez-Ramírez N, et al. 2008. Expression, characterization and synergistic interactions of Myxobacter sp. AL-1 Cel9 and Cel48 glycosyl hydrolases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 9:247–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rivas-Castillo AM, Yasbin RE, Robleto E, Nicholson WL, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2010. Role of the Y-family DNA polymerases YqjH and YqjW in protecting sporulating Bacillus subtilis cells from DNA damage. Curr. Microbiol. 60:263–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rosenberg SM, Thunlin C, Harris RS. 1998. Transient and heritable mutators in adaptative evolution in the lab and in nature. Genetics 148:1559–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Salas-Pacheco JM, Setlow B, Setlow P, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2005. Role of the Nfo (YqfS) and ExoA apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases in protecting Bacillus subtilis spores from DNA damage. J. Bacteriol. 187:7374–7381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Salas-Pacheco JM, Urtiz-Estrada N, Martínez-Cadena G, Yasbin RE, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2003. YqfS from Bacillus subtilis is a spore protein and a new functional member of the type IV apurinic/apyrimidinic-endonuclease family. J. Bacteriol. 185:5380–5390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schanz S, Castor D, Fischer F, Jiricny J. 2009. Interference of mismatch and base excision repair during the processing of adjacent UG mispairs may play a key role in somatic hypermutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:5593–5598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shapiro R. 1981. Damage to DNA caused by hydrolysis, p 3–12 In Seeberg E, Kleppe K. (ed), Chromosome damage and repair. Plenum Publishing Corp, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shapiro R, Weisgras JM. 1970. Bisulfite-catalyzed transamination of cytosine and cytidine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 24:839–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shapiro R, Pohl SH. 1968. The reaction of ribonucleosides with nitrous acid. Side products and kinetics. Biochemistry 7:448–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shapiro R, Shiuey SJ. 1969. Reaction of nitrous acid with alkylaminopurines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 174:403–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shida T, Ogawa T, Ogasawara N, Sekiguchi J. 1999. Characterization of Bacillus subtilis ExoA protein: a multifunctional DNA-repair enzyme similar to the Escherichia coli exonuclease III. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 63:1528–1534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Spizizen J. 1958. Transformation of biochemically deficient strains of Bacillus subtilis by deoxyribonucleate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 44:1072–1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sung HM, Yasbin RE. 2000. Transient growth requirement in Bacillus subtilis following the cessation of exponential growth. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1220–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sung HM, Yasbin RE. 2002. Adaptative, or stationary-phase, mutagenesis, a component of bacterial differentiation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 184:5641–5653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Téllez-Valencia A, Sandoval AA, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2003. The non-catalytic amino acid Asp446 is essential for enzyme activity of the modular endocellulase Cel9 from Myxobacter sp. AL-1. Curr. Microbiol. 46:307–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Urtiz-Estrada N, Salas-Pacheco JM, Yasbin RE, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2003. Forespore-specific expression of Bacillus subtilis yqfS, which encodes type IV apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease, a component of the base excision repair pathway. J. Bacteriol. 185:340–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vagner V, Dervyn E, Ehrlich D. 1998. A vector for systematic gene inactivation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 144:3097–3104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Vidales LE, Cárdenas LC, Robleto E, Yasbin RE, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2009. Defects in the error prevention oxidized guanine system potentiate stationary-phase mutagenesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 191:506–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yao M, Kow YW. 1996. Cleavage of insertion/deletion mismatches, flap and pseudo-Y DNA structures by deoxyinosine 3′-endonuclease from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 271:30672–30676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yao M, Hatahet Z, Melamede RJ, Kow YW. 1994. Purification and characterization of a novel deoxyinosine-specific enzyme, deoxyinosine 3′ endonuclease, from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 269:16260–16268 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yonekura S, Nakamura N, Yonei S, Zhang-Akiyama Q. 2009. Generation, biological consequences and repair mechanisms of cytosine deamination in DNA. J. Radiat. Res. 50:19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]