Abstract

The Neisseria meningitidis regulator NadR was shown to repress expression of the NadA adhesin and play a major role in NadA phase-variable expression. In this study, we identified through microarray analysis over 30 genes coregulated with nadA in the NadR mutant and defined members of the NadR regulon through in vitro DNA-binding assays. Two distinct types of promoter architectures (I and II) were identified for NadR targets, differing in both the number and position of NadR-binding sites. All NadR-regulated genes investigated were found to respond to 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (4HPA), a small molecule secreted in human saliva, which was previously demonstrated to induce nadA expression by alleviating NadR-dependent repression. Interestingly, two types of NadR 4HPA responsive activities were found on different NadR targets corresponding to the two types of genes identified by different promoter architectures: while NadA and the majority of NadR targets (type I) are induced, only the MafA adhesins (type II) are corepressed in response to the same 4HPA signal. This alternate behavior of NadR was confirmed in a panel of strains in response to 4HPA and after incubation in saliva. The in vitro NadR binding activity at type I and type II promoter regions is differentially affected by 4HPA, suggesting that the nature of the NadR binding sites may define the regulation to which they will be subjected. We conclude that NadR coordinates a broad transcriptional response to signals present in human saliva, mimicked in vitro by 4HPA, enabling the meningococcus to adapt to the relevant host niche.

INTRODUCTION

Neisseria meningitidis is a Gram-negative bacterium which colonizes the oropharynx mainly as a commensal, being carried asymptomatically by 5 to 10% of the healthy population (4, 39). For largely unknown reasons that are dependent on both the host and pathogen, in a small subset of carriers the meningococcus can invade the pharyngeal mucosal epithelium and, in the absence of bactericidal serum activity, disseminate into the bloodstream, causing septicemia. In a subset of cases, the bacteria can also cross the blood-brain barrier and infect the cerebrospinal fluid, causing meningitis.

Although extensive transcriptional regulation is expected to accompany the infection process of N. meningitidis, the role of only few of the transcriptional regulators in the pathogenic Neisseriae has been investigated to date. Two of the 36 putative transcriptional regulators in N. meningitidis strain MC58 (according to the Comprehensive Microbial Resource database, http://cmr.jcvi.org) are members of the MarR (multiple antibiotic resistance regulator) family of regulators, NMB1585 and NMB1843. The MarR family of prokaryotic transcriptional regulators includes proteins critical for control of virulence factor production, response to antibiotic and oxidative stresses, and catabolism of environmental aromatic compounds (45). Typically, MarR regulators bind to relatively short palindromic sequences consistent with the dimeric structure of the proteins, although the lengths of the inverted repeats and the spacing between half-sites are variable (45). The majority of the MarR family members are regulated by the noncovalent binding of low-molecular-weight signaling molecules (45). MarR family members typically act as repressors, although some have been shown to activate gene expression (9). The structure of the NMB1585-encoded protein has been resolved, and it was shown to bind to its own promoter DNA, but neither its target genes nor the signal to which it responds is known (26).

The NMB1843 transcriptional regulator is a homologue of FarR in gonococcus (with a sequence similarity of >98%), which was first described as a regulator of the farAB efflux pump that mediates gonococcal fatty acid resistance (19). The FarR regulator was shown to bind to three binding sites overlapping and upstream of the farAB promoter and repress expression of the efflux pump (18, 19). In contrast, NMB1843 has been reported to play no role in regulating fatty acid resistance in N. meningitidis, which exhibits high intrinsic fatty acid resistance (33, 34). Instead, NMB1843 was demonstrated to repress expression of the meningococcal adhesin NadA (neisserial adhesin A) (23, 33).

NadA is an important virulence factor of N. meningitidis implicated in colonization of the oropharynx, as it mediates bacterial adhesion to and invasion of mucosal cells (3, 5). NadA is one of the components of a recombinant vaccine currently in development against meningococcal serogroup B (11, 29). A knockout of the NMB1843 gene was unchanged in its sensitivity to fatty acids but adhered considerably more to epithelial cells than the wild type due to increased expression of nadA (33, 34). Due to the absence of a role in fatty acid resistance, the meningococcal FarR homologue NMB1843 was recently renamed NadR due to its main role in the regulation of NadA repression (23). A phase-variable repeat sequence, upstream of the nadA promoter region, alters the expression of NadA by controlling the transcriptional activity of the promoter (20, 21), and NadR was demonstrated to be the major mediator of this control (23). NadR binds to sequences flanking the variable repeat region, and changes in the number of repeats affect the ability of NadR to repress the promoter (23).

As is typical for MarR-like proteins, a small molecule ligand, 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (4HPA), was identified which is able to relieve the DNA binding activity of NadR and derepress/induce NadA expression (23). 4HPA is a catabolite of aromatic amino acids and is secreted in human saliva (43). This metabolite may act as a relevant niche signal to meningococci present in the oropharynx, which is bathed in saliva, for the induction of the NadA adhesin and other coregulated genes under NadR control. It has been in fact recently described that, even if being a highly specialized repressor of nadA, NadR can regulate, to a lesser extent, four other genes during exponential growth phase (35).

In order to identify genes that may be coregulated with nadA by NadR and the 4HPA molecule, in this study we analyze the global gene expression profile of the wild-type and the NadR null mutant strains. We elucidate the effect of the small molecule 4HPA in modulating NadR target gene expression. By characterizing the NadR regulon, we gain insights into a coordinated response in meningococcal expression that may be relevant during infection in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The N. meningitidis strains used in this study include MC58, 5/99, and 961-5945 and their respective NadR null mutant derivates MC-Δ1843, 5/99-Δ1843, and 961-Δ1843, described previously (23), and the LNP17094 and B3937 clinical isolates. N. meningitidis strains were routinely cultured, stocked, and transformed as previously described (16). When required, erythromycin and/or chloramphenicol antibiotics were added to culture media at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml, and 4HPA in aqueous solution was added to achieve final concentrations of 1 or 5 mM. Escherichia coli DH5α (14) and BL21(DE3) (41) cultures were grown in Luria–Bertani medium, and when required, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and/or isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) were added to achieve final concentrations of 100μg/ml, 20 μg/ml, and 1 mM, respectively.

Construction of NadR mutant and complementing strains.

DNA manipulations were carried out routinely as described for standard laboratory methods (32). The NadR mutants of the LNP17094 and B3937 strains were generated by transformation of the wild-type strains with pΔ1843ko::Cm (23) and selection on chloramphenicol, leading to the generation of LNP-Δ1843 and B39-Δ1843 strains, respectively. For complementation of the MC-Δ1843 NadR null mutant (23), the nadR gene under the control of the Ptac promoter was reinserted into the chromosome of MC-Δ1843 strain between the converging open reading frames (ORFs) NMB1428 and NMB1429, by transformation with pComEryPind-nadR. pCompEryPind-nadR is a derivative plasmid of the pSLComCmr (15), in which the nadR gene was amplified from the MC58 genome with the primer pair 1843-F and 1843-R2 and cloned as a 441-bp NdeI/NsiI fragment downstream of the Ptac promoter. The chloramphenicol resistance cassette of pSLComCmr was substituted with an erythromycin resistance cassette, amplified with primers EryXbaF and EryBamR, and cloned into the XbaI-BamHI sites (Table 1), generating pComEryPind-nadR. This plasmid was transformed into MC-Δ1843 for the generation of the ΔNadR_C complemented mutant strain, and transformants were selected on erythromycin. All transformants were tested by diagnostic PCR analysis for correct insertion by a double homologous recombination event, and the nadA promoter was amplified and sequenced in each transformant to ensure that the same numbers of repeats were present as in the derivative strain. The nadR gene in the complementation construct was expressed in an IPTG-inducible manner, and a final concentration of 10 μM resulted in expression levels similar to those of the wild type.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequencea | Site |

|---|---|---|

| 1843-F | attcacatATGCCTACCCAATCAAAACATGCG | NdeI |

| 1843-R2 | attcatgcatCGGCGTATTACGAGTTCAACGCATCCTCG | NsiI |

| Ery-XbaF | attcgtctagaGCAAACTTAAGAGTGTGTTGATAG | XbaI |

| ERI R BAM | atatatggatccGGGACCTCTTTAGCTTCTTGG | BamHI |

| 119rt-F | TGGCGTTACGACAATACGAT | |

| 119rt-R | AGTGTTGCCCTGTGTAGCAG | |

| 120rt-F | GCATGGATTATAACCTATCGATCTAA | |

| 120rt-R | TACGCTTGCTGTTCCCTGT | |

| 207rt-F | TGACCAAATTCGACACCGT | |

| 207rt-R | ATCGACACCGAGTTCTTTCC | |

| 401rt-L | AGGTATCGGTTTCGTTGTCC | |

| 401rt-R | TTGATTTCGCTGTCCCAATA | |

| 652-375rt-F | CGAATATTTCGCCGTTGAC | |

| 652-375rt-R | AAAGGGCGTATTGTTCTTGG | |

| 702rt-F | GATTTGCTGCTGTCGGACTA | |

| 702rt-R | GCCTATCCCGTTGGATAATG | |

| 865rt-F | ACCGCTGGTGGTATGATAGG | |

| 865rt-R | GCACCATTTGCACGAATAAC | |

| 955rt-F | TGTGCCGGTCAGGTTTACTA | |

| 955rt-R | GTTCGGATATTTCGCCAGTT | |

| 978rt-F | AAACACAAGCTCAACGCACT | |

| 978rt-R | GGGCAATCAGGGTCATAATC | |

| 980rt-F | TTTGAAACCGTTGTCGAAAG | |

| 980rt-R | GGCGCGTTGACCTTATAAAT | |

| 1277rt-F | AGACGCAGGAGCAGGATATT | |

| 1277rt-R | CCGTATTCTTCCGAAAGCTC | |

| 1476rt-F | ACGTTGCCATTTACAACGAA | |

| 1476rt-R | GTTCGGCGTTGGTAATTTCT | |

| 1478rt-F | CATCGGCAAACTGGTTCA | |

| 1478rt-R | CTCAAATGGTCGCGGTAGTA | |

| 1609rt-F | TACTACACCGGATTGTCCGA | |

| 1609rt-R | CTTCTTGATCGGCAACTTCA | |

| 1841rt-F | CCTTTGACCGATACCACTCC | |

| 1841rt-R | ATGACGATTTCGGTAAACCC | |

| 1842rt-F | TTTCAAACTTCGTTCCGTGA | |

| 1842rt-R | CCGTCATTGTAATGCCGTAA | |

| 1843rt-F | AGGGCGAGAAGCTGTATGAG | |

| 1843rt-R | CAGGTCTTTAAGCAGCAGCA | |

| 1844rt-F | ATGCGGTTTATAGCGTATTG | |

| 1844rt-R | TTAAGTCTCCAAGTTATCG | |

| 1994rt-F | GCTGGCACAGCTAATACTGC | |

| 1994rt-R | TCAGCTTTGTTCGTAGCGAT | |

| 2099rt-F | ACCTGCCTTATATCGAACCG | |

| 2099rt-R | AGGTTCAAATCATGCACACG | |

| 16S_F | ACGGAGGGTGCGAGCGTTAATC | |

| 16S_R | CTGCCTTCGCCTTCGGTATTCCT | |

| P207-F2 | CTCAAACAATACAAAGCCAAACAGG | |

| P207-R | GCCCATGGTTTGTTCCTTTGTTGAGGG | |

| P375-F | CCGCAATGGGTGGAAGCCGCCGC | |

| P652-F | ACAGTCAAAATGCCGTCTGAAAGCC | |

| P375-652R | GGAGGAGCAGGGTTTTCATAGCGGGG | |

| P401-F3 | GCCGACGCAGATTACCGCGCC | |

| P401-R | GCCGGAAATGCAAAATGAAACATTTTTTGG | |

| P0430-F | CAAAGGAACATTACTATGAAACC | |

| P0430-R | GTGTTGACTCATCATATTTCTCC | |

| P0535-F | CGGGCATACGACATTCTTTCCGC | |

| P0535-R | GACATTTCTTAACGGCAATGC | |

| P0702-F | CCCTGAGTCCTAGATTCCCGC | |

| P0702-R | CCGAAAAACCGTCATAACAAGATTTG | |

| P0955-F2 | TACCGGTTCGGAACGCCGCG | |

| P0955-R | CGTCCATCATGGCGTGCGC | |

| P0978-F2 | CGGCACACGCAACCGGCAATGCGGCGC | |

| P0978-R | CGAGTCCTGAAGACATAGAAATTCTCCG | |

| P0980-F2 | CGGCAAAGAATGTTACGGCGGGCGG | |

| P0980-R | CGCGTGGGATACCGATTTTCATCTCTG | |

| P1205-F | CCAACGAAGAACATATAGACTGGCTGG | |

| P1205-R | CAAGCACCCTGAATTTCATATCGG | |

| P1277-F | CCGGCGTTAAACGCCCCG | |

| P1277-R | CAGACAGGGACAAACCTTCTCACTCC | |

| P1476-F2 | GCAAATCCCGGCGCCGTTCC | |

| P1476-R | GGGCTTCAGACATTTTGCTTCC | |

| P1478-F2 | CAAGCCGCACGGAATCCGTCTG | |

| P1478-R | CGATGGCTGCATTCATAATCCGG | |

| P1609-F | CCTATCAGCTCCAGCAGATGC | |

| P1609-R | GCTCATCGGTGATTCCTCGG | |

| P1843-F2 | GAGCCGACGCGCCTGCCGATG | |

| P1843-sR2 | GGTAGGCATTGTTTAAGTCTC | |

| 1844-F | GGGAAAGAGCCGACGCGCCTG | |

| 1844-R | GCTATAAACCGCATCGGACGACTGG | |

| P2099-F | CCGCCTGTTCCTGCTGCC | |

| P2099-R | CCTCGTTCCTCATTTCAGACGGCC | |

| farA-S1 | CGGTATCTGTGTAGgaTcCTTCAGACGGCATGG | |

| farA-S2 | CGAACAGCAGCGTCAATGCCGTCAGG | |

| Nad-N1 | attcagatgcatGACGTCGACGTCCTCGATTACGAAGGC | NsiI |

| Nad-B1 | attcaggatcctacGCTCATTACCTTTGTGAGTGG | BamHI |

Capital letters indicate N. meningitidis-derived sequences; small letters indicate sequences added for cloning purposes. Underlined letters indicate the reported restriction sites.

Preparation of saliva samples.

Human saliva was obtained from healthy nonsmoking donors in the morning at least 10 h after eating and after rinsing the mouth with water. In order to minimize the degradation of the proteins, the sample was kept on ice during the collection process. Immediately after collection, the sample of human saliva was stored at −20°C.

Western blot analysis.

N. meningitidis colonies from overnight plate cultures were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1. Samples of 1 to 2 ml were harvested and the concentration normalized in 1× SDS-PAGE loading buffer (50 mM Tris Cl [pH 6.8], 2.5% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 10% glycerol, 5% beta-mercaptoethanol, 50 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) to a relative OD600 of 5. To prepare protein extracts from bacteria incubated with either 5 mM 4HPA or human saliva, N. meningitidis colonies from overnight GC plate cultures were resuspended in GC to an OD600 of 0.05. Liquid cultures were grown until mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.4), harvested, and resuspended in either GC, GC + 5 mM 4HPA, or 10%, 50%, or 90% human saliva in GC containing EDTA-free protease inhibitors cocktail (Roche). Bacteria were then incubated for 1 h with agitation at 37°C. A 1-ml sample of each liquid culture was harvested and resuspended in 100 ml of SDS-PAGE loading buffer. For Western blot analysis, 10 μg (roughly equivalent to 10 μl at an OD600 of 5) of each total protein sample in 1× SDS-PAGE loading buffer was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane using an iBlot Dry Blotting System (Invitrogen). Membranes were blocked overnight at 4°C by agitation in blocking solution (10% skim milk, 0.05% Tween 20, in PBS) and incubated for 90 min at 37°C with anti-NadA (5), anti-NadR (23), or anti-Maf (13) polyclonal sera in blocking solution. After being washed, the membranes were incubated in a 1:2,000 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Bio-Rad) or anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Dako), in blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature, and the resulting signal was detected using the Supersignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce).

RNA preparation.

Bacterial cultures were grown in liquid medium to an OD600 of 0.5 and then added to the same volume of frozen medium to bring the temperature immediately to 4°C. Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) as described by the manufacturer. RNA pools for microarray experiments were prepared from three independent cultures of bacteria; total RNA was extracted separately from each bacterial pellet, and 15-μg samples of each preparation were pooled together. Three independent pools were prepared for each strain.

Microarray procedures.

DNA microarray analysis was performed using an Agilent custom-designed oligonucleotide array as previously described (10). cDNA probes were prepared from RNA pools (5 μg) obtained from MC58 wild-type and MC-Δ1843 null mutant cells (see above) and hybridized as described by Fantappiè et al. (10). Three hybridizations were performed using cDNA probes from three independent MC58 and MC-Δ1843 pools, respectively, and the corresponding dye swap experiments (with MC58 and MC-Δ1843 pools inversely labeled with the Cy3 and Cy5 fluorophores) were also performed. Differentially expressed genes were assessed by grouping all log2 ratios of the Cy5 and Cy3 values corresponding to each gene, within experimental replicas and spot replicas, and comparing them against the zero value by Student's t test statistics (one tail).

RT-PCR.

Approximately 4 μg of the total RNA preparation was treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega). RNA was then reverse transcribed using random hexamer primers and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega) as recommended by the manufacturer. For negative controls, all RNA samples were also incubated without reverse transcriptase. Primer pairs for each target gene were designed and optimized and are listed in Table 1 named with the number according to their NMB annotation and rt to denote real-time PCR (RT-PCR). Primers 16S_F and 16S_R were used for the 16S rRNA normalization control (Table 1). All RT-PCRs were performed in triplicate using a 25-μl mixture containing cDNA (5 μl of a 1/5 dilution), 1× brilliant SYBR green quantitative PCR master mixture (Stratagene), and approximately 5 pmol of each primer. Amplification and detection of specific products were performed with an Mx3000 real-time PCR system (Stratagene) using the following procedure: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 30 s, and then a dissociation curve analysis. The 16S rRNA gene was used as the endogenous reference control, and relative gene expression was determined using the 2−ΔΔCT relative quantification method.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

For gel shift experiments, a probe corresponding to the respective promoter region (150 to 280 bp) of the first gene in probable operons containing NadR target genes was amplified using primers listed in Table 1 and named with P (for promoter) and a number according to the NMB annotation. Two pmol of each fragment was then radioactively labeled at the 5′ end with 30 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol; NEN) using 10 U of T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England BioLabs). The unincorporated radioactive nucleotides were removed using TE-10 Chroma Spin columns (Clontech).

The expression and purification of the NadR recombinant protein were carried out as fully described previously (23). For each binding reaction, 40 fmol of labeled probe was incubated with recombinant NadR in a 25-μl final volume of Gelshift binding buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol) with 2 μg salmon sperm DNA as a nonspecific competitor, in the presence or absence of 4HPA, for 15 min at room temperature, and run on 6% native polyacrylamide gels buffered with 0.5× TBE, at 100 V for 90 to 180 min at 4°C. Gels were dried and exposed to autoradiographic films at −80°C and radioactivity was quantified using a phosphorimager and the Image Quant software (Molecular Dynamics).

3C mutation scanning.

To perform the 3C mutation scanning of the single NadR binding sites on the nadA and mafA1 promoters, DNA oligonucleotides corresponding to the forward and reverse strands of either the wild-type NadR-protected sequences from DNAI footprints or mutated sequences, in which sequential triplicate nucleotides were substituted with CCC, were ordered from Sigma. A 100-pmol portion of each oligonucleotide pair was annealed in annealing buffer (10 mM Tris HCl [pH 8], 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) by using a standard thermal cycler. The mix was heated to 95°C and left at this temperature for 5 min, followed by ramp cooling to 25°C over a period of 45 min. The annealed oligonucleotides were stored at −20°C, 5′ end labeled, and submitted to EMSA analysis as described in the previous section.

DNase I footprint.

The nadR, putA, and mafA1 promoter regions were amplified with the primer couples P1843-F2/P1843-sR2, P401-F3/P401-R, and P375-F/P375-652R, respectively. The PCR products were purified and cloned into pGEMT vector (Promega) as 258-, 280-, and 267-bp fragments generating pGEMT-P1843, pGEMT-P401, and pGEMT-P375. A 2-pmol sample of each plasmid was 5′ end labeled by T4 polynucleotide kinase with [γ-32P]ATP after digestion at either the NcoI or SpeI site of the pGEMT polylinker. Following a second digestion with either SpeI or NcoI, the labeled probes were separated from the linearized vector by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) as described previously (23). DNA-protein binding reactions were carried out for 15 min at room temperature in footprint buffer (10 mM Tris HCl [pH 8], 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.05% NP-40) containing 40 fmol of labeled probe, 200 ng of sonicated salmon sperm as the nonspecific competitor, and concentrations of NadR-purified protein as indicated in the figures. Samples were then treated with 0.03 U of DNase I (Roche) for 1 min at room temperature. DNase I digestions were stopped, and samples were purified, loaded, and run on 8 M urea–6% polyacrylamide gels as described previously (7). A G+A sequence reaction was performed (22) for each probe and run in parallel to the footprinting reactions.

Computational analysis.

Quantification of the signals from Western blot bands was performed by using a PhosphorImager and ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics).

Microarray data accession numbers.

The array layout was submitted to the EBI ArrayExpress and it is available with the identifier A-MEXP-1967. The entire set of supporting microarray data has been deposited in the ArrayExpress public database under the accession number E-MTAB-803.

RESULTS

Global analysis of gene expression in the NadR mutant.

In order to identify NadR-regulated genes in N. meningitidis we used a custom-made Agilent oligonucleotide microarray to compare the transcriptional profiles of MC58 wild-type and MC-Δ1843 NadR mutant strains grown until mid-exponential phase. Three independent two-color microarray experiments were performed comparing pooled RNA from triplicate cultures of each strain, as well as three dye swap experiments. The results obtained from these experiments were averaged after slide normalization, and 28 differentially expressed genes were identified with a log2 ratio of >0.9 transcriptional change and a t test P value of ≤0.01 (Table 2). When we reduce the criterion to a log2 ratio of >0.6 in the original three experiments (excluding the dye swap), we can select another nine differentially upregulated genes in the NadR mutant with a P value of ≤0.01 (Table 2). RT-PCR analyses were consistent with the microarray data (Table 2) confirming the putative NadR-regulated genes identified in this global gene expression analysis. A total of 31 genes were upregulated, whereas 6 were downregulated in the NadR mutant. The contiguous genes that are in the same orientation and exhibiting similar regulation have been grouped into likely operons (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Differentially regulated genes in NadR null mutant

| Gene name | Oria | Function | Microarray results, Δ1843 vs. MC58wt |

RT-PCR fold change |

Gel shifte | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg (fold change) | P | Δ1843 vs. MC58 | NadR_C vs. Δ1843 | ||||

| NMB0119 | ↑ | Hypothetical protein | −4.5b | 1.8E−14 | −2.7 | 1.1 | |

| NMB0120 | | | Hypothetical protein | −8.4b | 2.3E−06 | −4.4 | 1.1 | ND |

| NMB0207 | ↑ | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, gapA | 4.0b | 8.5E−07 | 5.4 | −5.9 | + |

| NMB0375 | | | MafA1 adhesin, mafA1 | 2.1b | 4.4E−05 | 2.3 | −2.3 | + |

| NMB0374d | ↓ | MafB1 adhesin, mafB1 | 1.3b | 4.7E−02 | ND | ND | |

| NMB0401 | ↓ | Proline dehydrogenase, putA | 1.9b | 1.2E−04 | 2.4 | −3.1 | + |

| NMB0429 | | | Hypothetical protein, putative regulatory protein | 1.9b | 3.1E−06 | ND | ND | + |

| NMB0430 | | | Putative carboxyphosphonoenolpyruvate phosphonomutase, prpB | 1.9b | 9.6E−04 | ND | ND | |

| NMB0431 | ↓ | Methylcitrate synthase/citrate synthase 2, prpC | 1.9b | 1.6E−04 | ND | ND | |

| NMB0652 | | | MafA2 adhesin, mafA2 | 2.0b | 1.4E−04 | 2.3 | −2.3 | + |

| NMB0653 | | | MafB-related protein, mafB2 | 1.9b | 6.8E−07 | ND | ND | |

| NMB0654 | ↓ | Hypothetical protein | 2.1b | 3.6E−03 | ND | ND | |

| NMB0865 | ↑ | Hypothetical protein | 1.9b | 4.0E−05 | 2.8 | −5.5 | ND |

| NMB0866 | | | Hypothetical protein | 2.0b | 8.9E−03 | ND | ND | |

| NMB0955 | | | 2-Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, E1 component, sucA | 1.9b | 2.7E−07 | 2.9 | −3.2 | + |

| NMB0956d | ↓ | 2-Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, sucB | 1.6b | 2.7E−02 | ND | ND | |

| NMB1205 | ↓ | Hypothetical protein | 2.4b | 8.4E−04 | ND | ND | + |

| NMB1277 | ↑ | Transporter, BCCT family | 1.9b | 1.2E−06 | 1.7 | −4.5 | + |

| NMB1299 | ↓ | Sodium- and chloride-dependent transporter | 2.2b | 3.2E−03 | ND | ND | − |

| NMB1476 | ↑ | Glutamate dehydrogenase, NAD specific, gluD | 4.1b | 2.3E−11 | 7.9 | −11.1 | + |

| NMB1477 | | | Hypothetical protein, comA competence protein | 2.3b | 7.0E−03 | ND | ND | |

| NMB1478 | | | Phosphoglycolate phosphatase | 2.3b | 3.6E−05 | 3.7 | −2.6 | − |

| NMB1479 | ↓ | Regulatory protein RecX | 2.2b | 2.1E−06 | ND | ND | |

| NMB1841 | ↑ | Mannose-1-phosphate guanyltransferase-related protein | −8.5b | 1.1E−16 | −3.8 | 1.0 | |

| NMB1842 | | | Putative 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-hydroxylase | −14.1b | 0.0E + 00 | −5.6 | 0.9 | |

| NMB1843 | | | Transcriptional regulator | −25.5b | 8.3E−09 | −12.3 | ND | + |

| NMB1844 | | | Hypothetical protein | −3.0b | 4.3E−06 | −1.6 | 1.1 | − |

| NMB1994 | ↓ | Putative adhesin/invasin, nadA | 59.6b | 0.0E + 00 | 97.3 | −133 | + |

| NMB0535 | ↓ | Glucose/galactose transporter, gluP | 1.9c | 3.6E−04 | ND | ND | − |

| NMB0702 | ↓ | Competence protein ComA | 1.8c | 1.1E−03 | 1.9 | −7.1 | − |

| NMB0978 | ↑ | NAD(P) transhydrogenase, beta subunit, pntB | 1.7c | 6.4E−03 | 4.3 | −2.9 | |

| NMB0979d | | | Hypothetical protein | 1.6c | 1.3E−01 | ND | ND | |

| NMB0980d | | | NAD(P) transhydrogenase, alpha subunit, pntA | 1.6c | 2.8E−02 | 1.8 | −1.2 | + |

| NMB1609 | ↑ | trans-Sulfuration enzyme family protein, metZO-succinylhomoserine sulfhydrolase | 1.7c | 2.2E−06 | 2.3 | −4.0 | + |

| NMB2097 | ↑ | Hypothetical protein, pykA pyruvate kinase | 1.5c | 2.0E−04 | ND | ND | |

| NMB2098 | | | Conserved hypothetical protein | 1.6c | 4.1E−03 | ND | ND | |

| NMB2099 | | | Conserved hypothetical protein, putative 5-formyltetrahydrofolate cyclo-ligase | 1.7c | 4.7E−03 | 2.4 | −4.3 | + |

Ori, orientation. Genes are grouped into likely operons as predicted by their similar orientation and proximity. Vertical solid lines represent the first and following genes in the predicted operon. Arrows pointing up represent the last gene in the operon in the reverse strand of the genome. Arrows pointing down represent the last gene in the operon in the forward strand of the genome.

Average values from three separate microarray experiments and three dye swap experiments.

Average values of three separate microarray experiments.

Genes with values outside the criteria used are included when contiguous and oriented similarly to upstream or downstream coregulated genes.

ND, not determined.

In order to confirm that the regulation is NadR dependent, we complemented the MC-Δ1843 mutant by reintroducing the nadR gene under the control of an inducible Ptac promoter in a different locus in the genome, generating the strain ΔNadR_C. By altering the concentration of IPTG in the growth medium of the ΔNadR_C strain, we obtained a level of NadR expression in the complemented strain comparable to that of the wild type (data not shown) and prepared total RNA from this strain under the same conditions used for the microarray experiments. We measured the transcriptional levels of the target genes by RT-PCR in the complemented ΔNadR_C strain and observed that for all of the genes tested that were upregulated in MC-ΔNadR (MC-ΔNadR versus MC58), complementation of the mutant (NadR_C versus MC58) restored their expression to levels similar to or slightly lower than the wild-type level. In contrast, none of the downregulated genes was restored to wild-type level through complementation of the mutant, suggesting that these effects were not dependent on the activity of the NadR protein. Among the six downregulated genes, NMB1844, NMB1842, and NMB1841 are contiguous and in the same orientation to the NadR-encoding gene NMB1843 and may be polarly affected by the insertion of the antibiotic resistance cassette for the generation of the mutant. The lack of complementation of deregulation of NMB0119 and NMB0120 is instead likely to be due to a NadR-independent effect such as phase variation or secondary mutations.

These data suggest that NadR functions solely as a repressor protein, negatively regulating multiple loci. Through global gene analysis we identify at least 18 hypothetical operons/transcriptional units coding for 31 genes whose expression was repressed by NadR.

Functional classification of the NadR-regulated genes.

Among all NadR-regulated genes, the NadA adhesin shows the most altered expression profile in the Δ1843 mutant. Interestingly, two of the three mafA (multiple adhesin family A) loci were also repressed by NadR. The NadR-regulated MafA1 and MafA2 (encoded by NMB0375 and NMB0652) are expressed in MC58, while mafA3 is a pseudogene containing a frameshift. The maf loci, similarly to the locus of the type IV pili, consist of downstream silent cassettes of the expressed genes and are thought to undergo antigenic variation through recombination of the coding sequences with the silent cassettes (2). The maf genes encode a family of variable lipoproteins originally identified as glycolipid-binding proteins in pathogenic Neisseria (2, 25, 28), which have been shown to adhere to glycolipid receptors on human cells (6, 40) and thus predicted to be adhesins. While only approximately 40% of circulating meningococcal strains carry the nadA gene, which is thought to have been acquired by horizontal gene transfer, all meningococcus strains carry multiple loci expressing the Maf adhesins.

In addition to outer membrane adhesins, NadR is able to repress the expression of a number of genes coding for inner membrane transporters, including those involved in transport of sugars (NMB0535, glucose/galactose transporter), compatible solutes (NMB1277, encoding a putative glycine betaine transporter), transporters of unknown substrates (NMB1299, encoding an Na- and Cl-dependent transporter), and even DNA (NMB0702, encoding the ComA protein). NadR also regulates genes involved in energy metabolic pathways, including the NMB0401 (putA encoding proline dehydrogenase), NMB1476 (gluD encoding glutamate dehydrogenase), and NMB0955-957 (sucAB-lpdA1 encoding 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase) genes involved in sequential steps of l-proline and glutamate catabolism, along with other genes that may be involved in amino acid metabolism (NMB1609, NMB1842) and other energy metabolic processes [NMB0207, gapA1 encoding a glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; NMB0430-431 coding for a putative 2-methylcitrate pathway; NMB1478, gph encoding phosphoglycolate phosphatase; and NMB0978-980, pntAB encoding NAD(P) transhydrogenase] as well as a number of hypothetical genes (NMB0865/0866, NMB1477, NMB2099-2097) whose function is unknown. Included also in the list are two possible regulators of gene expression: NMB1479, coding for a putative transcriptional regulator, and NMB1205, which synthesizes a small noncoding regulatory RNA recently named AniS (10).

Binding of NadR to its targets.

It has been previously demonstrated that NadR binds to the nadA and farAB promoter regions (23, 33), although no transcriptional regulation of farAB is thought to occur in meningococcus (33). Moreover, it has been recently reported that NadR-regulated genes were not directly bound by the protein (35), suggesting an indirect NadR regulation. To determine which of the NadR-repressed genes are under direct regulation of NadR, we amplified by PCR the upstream promoter regions of identified target genes and performed gel shift analysis with purified recombinant NadR. We found that out of 19 target promoter regions tested, 14 are bound by the NadR recombinant protein (Table 2). Interestingly, NadR binds its own promoter, suggesting a possible autoregulation. The five promoter regions not directly bound by NadR were those of NMB0535, NMB0702, NMB1299, NMB1844, and gph (NMB1478), although we cannot exclude the possibility that the promoters and therefore the NadR regulatory sites are further upstream than the regions tested.

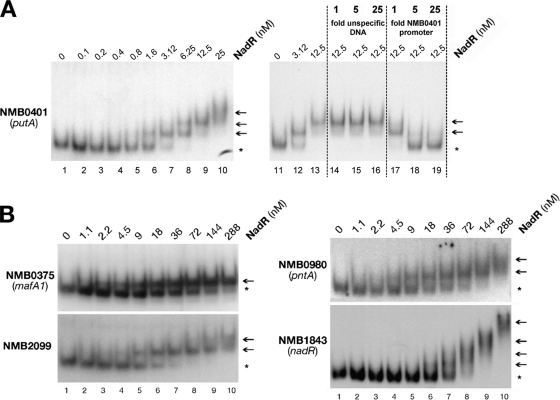

In order to demonstrate the specificity of NadR binding on its targets, a gel shift experiment on the promoter region of NMB0401 (putA) was performed in the presence of increasing concentrations of sonicated salmon sperm DNA (nonspecific competitor) or cold putA promoter (specific competitor) (Fig. 1A). One slow-migrating radioactive complex is formed by adding approximately 3 nM NadR protein to the labeled putA promoter. A second complex appears by increasing the concentration of NadR to 12.5 nM. A 1-fold portion of cold putA promoter probe is sufficient to abolish the higher complex, and 5-fold completely prevents the binding of NadR to the labeled probe. Instead, up to 25-fold of nonspecific competitor had no effect on protein-DNA complex formation, showing that NadR binds specifically to this promoter gene.

FIG 1.

NadR binds to its target genes in a specific way. (A) Gel shift analysis of NMB0401 (putA) promoter region. In the left panel 40 fmol of labeled probe was incubated with increasing amounts of NadR protein corresponding to the indicated concentrations. To test the specificity of NadR binding at the NMB0401 promoter region, in the right panel the same amount of probe was incubated either without or with increasing amounts of nonspecific (sonicated salmon sperm DNA) or specific competitor DNA (not radioactively labeled NMB0401 promoter probe), in the presence of the indicated concentrations of NadR protein. (B) A representative panel of gel shift experiments reported in Table 2 is shown. Promoter regions of indicated targets were amplified by PCR and radioactively end labeled. A 40-fmol sample of labeled probe was incubated with 2 μg of nonspecific competitor DNA and increasing amounts of NadR. Asterisks indicate free probes, and arrows indicate DNA-protein complexes.

A panel of representative gel shift experiments from Table 2 is shown in Fig. 1B. All these gel shifts were performed in the presence of a more than 10-fold excess of nonspecific competitor DNA in order to avoid nonspecific NadR binding. It is worth noting that with the exception of the promoter regions of NMB0375 (Fig. 1B) and NMB0652 (data not shown) genes, coding for MafA1 and MafA2, respectively, all other promoters exhibit multiple DNA-protein complexes and therefore are likely to contain multiple binding sites for NadR.

We conclude that NadR can bind to the upstream promoter region in vitro of at least 14 transcriptional units consisting of 26 genes, confirming that these genes are members of the NadR regulon. NadR regulation of the other genes may occur through indirect mechanisms such as the regulation of an intermediate regulating factor.

NadR binding to the farAB promoter.

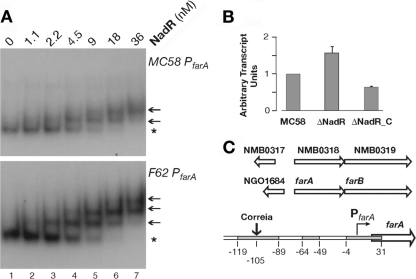

The farAB promoter region has been reported to be a target for binding but not regulation by NadR (33). In the microarray analysis we did not find the farAB genes among the NadR-regulated genes; nonetheless, we evaluated the binding of NadR to the farAB promoter region, and we found that it binds with a relative high affinity to this region (Fig. 2A). We also performed RT-PCR to measure levels of farAB transcript in total RNA extracts from the MC58 wild-type, MC-ΔNadR mutant, and ΔNadR_C complemented strains. The results in Fig. 2B show that the farAB transcript was upregulated by 1.6-fold in the mutant and was restored to slightly below wild-type levels through complementation. This suggests that NadR represses farAB to a very low level. Lee and colleagues (18) have shown through DNase I footprinting that gonococcal FarR, the homologue of NadR, binds to two high-affinity and one low-affinity binding sites in the farAB promoter, similar to the promoter architecture that was described for NadR binding on the nadA meningococcal promoter (reference 23 and schematic representation in Fig. 3B). Comparison of the sequence of the farAB promoter region in MC58 and gonococcus reveals high conservation of the promoters (95% nucleotide identity) apart from the insertion of a Correia element that disrupts one of the putative analogous FarR binding sites in MC58 (Fig. 2C). We performed gel shift analysis of NadR and probes of the farAB promoter regions of meningococcus and gonococcus. Figure 2A shows that NadR binds to both promoter regions, exhibiting three distinct DNA-protein complexes with the gonococcal farAB promoter and two distinct complexes with the MC58 farAB probe.

FIG 2.

Analysis of NadR binding to farAB. (A) Binding of NadR to the meningococcal and gonococcal farAB sequences. The farAB promoter was amplified from MC58 or F62 genomic DNA with FarAS1 and FarAS2 primers and end labeled. Labeled probes (20 to 40 fmol) were incubated with increasing amounts of NadR protein corresponding to 0, 1.1, 2.2, 4.5, 9, 18, or 36 nM for lanes 1 to 7, respectively. Asterisks indicate free probe, and arrows indicate DNA-protein complexes. (B) RT-PCR analysis of farA transcripts from total RNA of the MC58 wild-type strain (MC58), the MC-Δ1843 NadR mutant strain (Δ1843), and the complemented mutant strain (ΔNadR_C). RT-PCR was performed in triplicate on three independent biological replicates, and the average values are shown. The P values determined by Student's t test are ≤0.05 for all strains. (C) Diagram indicating the arrangement of the farAB locus and promoter in MC58 and N. gonococcus F62 from the published genome sequences. The gray boxes show the region of the farAB promoter protected by FarR in footprinting experiments (18), with numbers referring to the transcriptional start of the mapped farAB promoter (indicated as a bent arrow). The MC58 sequence is 95% identical to that of gonococcus, except for the insertion of a Correia element in the upstream binding site.

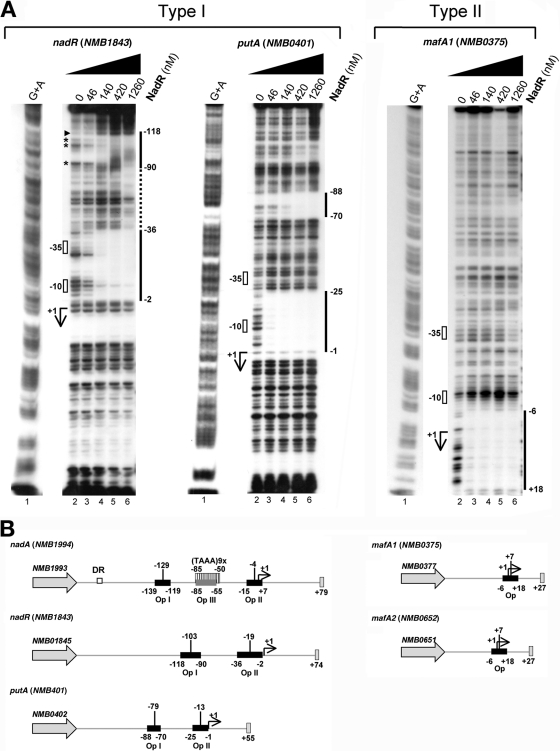

FIG 3.

Type I and type II genes have different promoter architectures. (A) DNase I footprint analyses of NadR on a representative panel of the promoter regions of its target genes. A 40-fmol sample of each probe was incubated with increasing amounts of NadR purified protein as indicated and then cleaved with DNase I. Regions of protection are indicated with vertical unbroken lines. Regions of nonspecific protection, possibly due to multimerization of NadR purified protein, are indicated with vertical dotted lines. Hypersensitive bands are marked by an arrowhead; protected disappearing bands are indicated with asterisks. The predicted +1, −10, and −35 locations of each promoter region were deduced from the DNA sequences and are properly located with respect to the G+A sequences. The positions of NadR protected regions are also indicated. Two classes of promoter architectures are indicated as type I and type II. (B) Schematic representations of type I and type II promoter regions. The structure of the nadA promoter is reported as previously described (20, 21, 23). The low-affinity operator III (Op III) at the TAAA repeats tract is represented by a dark gray box. Regions bound and protected by NadR in DNase I footprint analysis are represented by black boxes. The putative +1 regions of putA, nadR, mafA1, and mafA2 promoters are shown. The center of each NadR binding site is reported as well. DR, direct repeat (border of region of horizontal transfer).

Taken together, these observations suggest that the Correia element may interfere with NadR repression of the farAB promoter either by disrupting NadR binding at one site or by altering the structure and regulation of the meningococcal farAB promoter through the introduction of other sequences. It has been recently demonstrated (38) that Correia elements may drive transcription by inserting strong promoter sequences. Therefore, the insertion of the Correia element, providing a new promoter sequence, may override the NadR regulation of farAB and fatty acid resistance in meningococcus. Interestingly, a similar occurrence, the insertion of a Correia element within the promoter of the mtrCDE operon, has rendered the mtrCDE-encoded efflux pump of meningococcus independent of the MtrA and MtrR regulation that is observed in gonococcus (31).

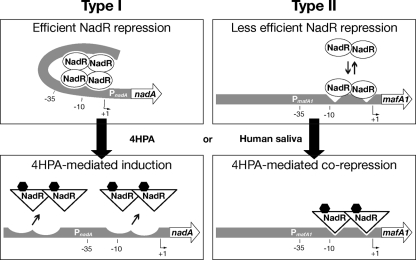

The NadR target genes can be classified in two types regarding their promoter architecture.

The previously described promoter region of nadA includes two distally spaced high-affinity binding sites for NadR (named OpI and OpII) and one with lower affinity interposing the others (named OpIII) (reference 23 and schematic representation in Fig. 3B). The presence of multiple NadR binding sites was suggested by gel shift analysis on all NadR identified targets except for NMB0375 and NMB0652. To better understand possible differences between promoter architectures of NadR-regulated genes, we performed DNase I footprint analysis of NadR purified protein on a representative panel of promoter regions (Fig. 3A). Both the promoter region of nadR (NMB1843) and putA (NMB0401) display two distally spaced NadR protected regions, one overlapping the predicted promoter sequences and the second upstream. This promoter architecture is comparable to that of the well-known promoter region of NadA (Fig. 3B) where the OpII overlaps the −10 box of the promoter and the OpI is distally spaced. On the other hand, the promoter region of mafA1 (NMB0375) (Fig. 3A and schematic representation in Fig. 3B) comprises only one binding site for NadR which overlaps the +1 and is downstream of the promoter.

Taken together, these data suggest the existence of two types of promoter architecture for NadR-regulated genes. Type I genes, including nadA and the majority of genes of the regulon, have multiple NadR binding sites and in particular two high-affinity sites, one overlapping the promoter (centered at −4, −19, and −13 positions for nadA, nadR, and putA, respectively) and one distally upstream (centered at −129, −103, and −79, respectively); type II genes, including the mafA coding genes NMB0375 and NMB0652, have one single NadR binding site centered at the +7 position of the promoter region.

Ligand-responsive regulation of NadR target gene expression by 4HPA.

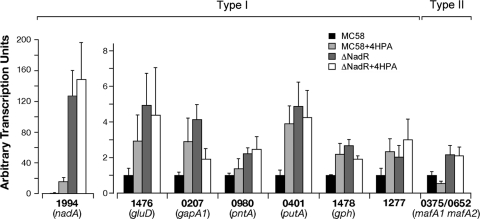

We have previously shown that a small molecule, 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (4HPA), regulates NadR-mediated repression of NadA expression in meningococcus (23). Therefore, we investigated the 4HPA-responsive regulation of the genes belonging to the NadR regulon. To understand the in vivo effect of the small molecule on target gene expression, we quantitatively analyzed the transcriptional level of selected target genes in the MC58 wild-type and NadR null mutant in the presence or absence of 5 mM 4HPA, using RT-PCR (Fig. 4). Surprisingly, we found that not all targets respond in a similar fashion to the 4HPA inducer molecule and two classes of gene targets could be defined, corresponding to the two types of genes identified due to their promoter region architectures. We found that the expression of most genes was induced by the 4HPA molecule (type I genes), either partially (i.e., nadA) or fully (i.e., putA, gph, nmb1277) with respect to the maximal derepression achieved in the NadR mutant. Interestingly the farA transcript was also induced in MC58 by 4HPA to levels similar to those of the mutant (data not shown); however, it is likely that these subtle differences are not biologically significant, as previous reports have clearly shown that NadR (named FarR in those studies) is not involved in fatty acid resistance mediated by the FarAB efflux pump in meningococcus which exhibits high intrinsic fatty acid resistance (33, 34). Intriguingly, we found that only the mafA genes (type II genes) expression responds in the opposite way to 4HPA, with mafA transcription being repressed in the presence of 4HPA and suggesting that this small molecule acts as a corepressor of NadR at the mafA1 and mafA2 promoters. In the NadR mutant strain, 4HPA-dependent regulation is largely absent, indicating that NadR is the mediator of the 4HPA transcriptional responses.

FIG 4.

Effect of 4HPA on gene expression. RT-PCR analysis of NadR target transcripts in total RNA prepared from the wild-type (MC58) and MC-ΔNadR mutant strains (ΔNadR) after growth in the presence or absence of 5 mM 4HPA. RT-PCR was performed in duplicate on three independent biological replicates, and the average values are shown. The primers used in qRT-PCR for mafA1 and mafA2 genes cannot distinguish between the NMB0375 and NMB0652 genes, as the sequences are identical. Two types of transcriptional patterns can be detected, type I (4HPA induced) and type II (4HPA repressed). It is worth noting that 4HPA results in the reduction of expression of the nmb0207 (gapA1) gene in the NadR null mutant, suggesting that gapA1 is subjected to a NadR-independent regulation that is also 4HPA responsive.

This analysis suggests that while NadR represses all genes in its regulon, 4HPA may act as an inducer (type I genes) or a corepressor (type II genes), resulting in alternative NadR-mediated responses in vivo, which can be at least partially due to the differential promoter architectures of the two types of NadR targets.

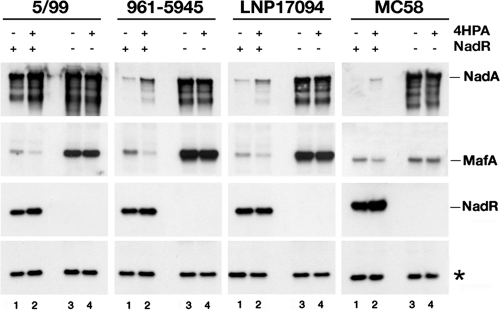

The NadR-dependent regulation of NadA, MafA, and NadR itself is common among meningococcal strains.

In order to investigate whether NadR-dependent regulation of NadA and MafA protein expression was exhibited by other strains, we extended our studies to a larger panel of meningococcal strains. Western blot analyses were carried out on the wild-type strains and their respective NadR mutant strains grown in the presence or absence of 4HPA (Fig. 5). Expression of NadA and MafA is variable between strains, while NadR is expressed to essentially the same level (lanes 1). All NadR null mutants exhibited higher levels of NadA and MafA than their respective wild types (lanes 3 versus 1), confirming the NadR repression of both nadA and mafA genes. In all the wild-type strains, the 4HPA molecule results in induction of both NadA and, to a lesser extent, NadR and corepression of MafA (lane 2 versus lane 1), while it had no effect on NadA or MafA expression in the NadR mutants (lane 4 versus lane 3), indicating that the effects of 4HPA are NadR dependent.

FIG 5.

NadR-regulated adhesin responses in a broad panel of meningococcal strains. Western blot analysis of wild-type (lanes 1 and 2) and corresponding NadR knockout (lanes 3 and 4) cultures of the indicated strains grown in the presence (lanes 2 and 4) and absence (lanes 1 and 3) of 1 mM 4HPA as indicated, showing NadA, MafA, and NadR protein levels. The nadA promoters in the 5/99, 961-5945, LNP17094, and MC58 strains exhibit 8, 12, 12, and 9 copies, respectively, of the phase-variable TAAA repeat, between the two high-affinity NadR binding sites, which affects the ability of NadR to repress NadA expression (23). The NadA protein migrated at a molecular mass of 98 kDa and corresponds to the trimeric form of the protein (5) (all coinduced faster-migrating bands are NadA dependent, as they are absent in the isogenic NadA mutant [data not shown]), and the MafA band migrates at 36 kDa and corresponds to both MafA1 and MafA2 proteins coded for by the NMB0375 and NMB0652 genes whose sequences are 100% identical. This band is absent in Western blots of extracts from the NMB0375 and NMB0652 double mutant (13) (data not shown). A nonspecific band indicated with an asterisk is reported as a loading control.

Taken together, these results suggest that both the NadR-dependent regulation of NadA and MafA and the 4HPA activity as an inducer of nadA and a corepressor of mafA are not restricted to the MC58 strain but are common throughout different meningococci. Furthermore, it would appear that the level of NadR itself is induced by 4HPA, most probably through alleviation of autoregulatory repression of its own promoter.

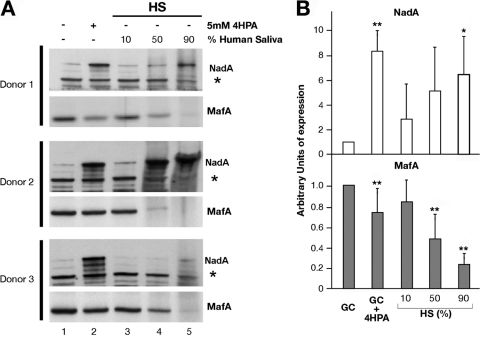

Incubation with human saliva has the same effect on NadA and MafA expression as 4HPA.

It has been previously demonstrated that the 4HPA molecule is a catabolite of aromatic amino acids secreted in human saliva (43). To test whether the effects due to 4HPA in vitro may have biological relevance, we tried to achieve similar results with human saliva. Mid-log cultures of MC58 were incubated for 1 h either with 4HPA or with increasing amount of human saliva from three different donors. Total protein extracts were obtained, and the expression levels of NadA and MafA were analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 6A). The Western blots show the induction of NadA and the repression of MafA following incubation with 4HPA (compare lanes 2 and 1 of each blot), and, even if with much greater experimental variability, the same results are obtained following incubation with increasing concentrations of human saliva from three donors (compare lanes 3, 4, and 5 to lane 1).

FIG 6.

Human saliva has the same activity of 4HPA on NadA and MafA expression. (A) Western blot analyses of total protein of mid-log cultures of MC58 incubated for 1 h either with 4HPA (lane 1) or with increasing amount of human saliva (HS) from three different donors (lanes 3, 4, and 5), as indicated. The levels of NadA and MafA proteins are shown. (B) Histogram representing the average expression levels of NadA (above) and MafA (below). The average values were calculated by quantification of Western blot bands signals from two independent experiments with human saliva of each donor (six experiments in total). Expression levels of NadA and MafA of cultures grown solely in GC medium were set to 1 arbitrary unit. To note that for the quantification, Western blot bands were normalized for a nonspecific band, indicated with an asterisk in panel A, in order to avoid non 4HPA- or NadR-dependent effects due to possible protein degradation in saliva. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, both versus the growth in GC.

Figure 6B shows a histogram with average values of quantified signals of Western blot bands from six independent experiments. While NadA is induced by 4HPA as well as by 90% human saliva, MafA expression is corepressed by both 4HPA and saliva at 50% and 90% concentrations, in a statistically relevant manner with respect to its basal level in GC growth.

This analysis suggests that the 4HPA molecule used in our experiments mimics a signal present in the human saliva, which produces the same regulatory effects on nadA and mafA expression.

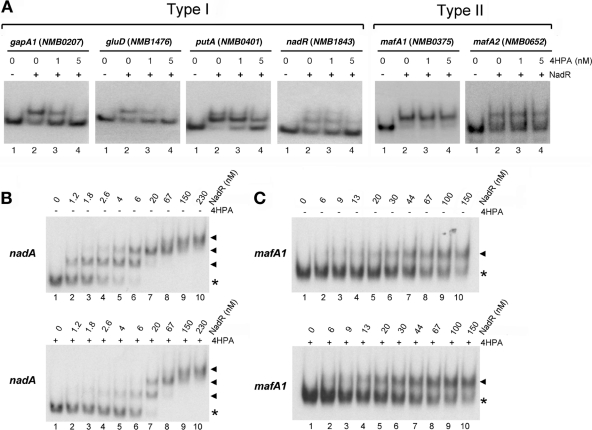

4HPA has differential activity on NadR binding to type I and type II promoters in vitro.

We previously reported that the 4HPA molecule can attenuate the binding of NadR to the nadA promoter in vitro (23), supporting the idea that it interacts with the protein and alters its DNA-binding activity. To investigate the role of 4HPA on the in vitro activity of NadR in binding to both type I and type II promoters, we performed gel shift analysis in the presence of NadR and increasing amounts of 4HPA on a selected panel of target promoter regions (Fig. 7A).We demonstrate that for type I (gapA1, gluD, putA, nadR) promoters, 4HPA is able to inhibit the NadR-DNA binding in vitro in a dose-dependent manner, similarly to what we reported for nadA (23). However, the addition of 4HPA had no significant effect on binding of NadR at the type II (mafA1 and mafA2) promoters. In a parallel and complementary set of experiments, we performed gel shift analysis on the promoters of nadA and mafA1 with increasing amounts of NadR purified protein in the presence or absence of 5 mM 4HPA (Fig. 7B and C). While 4HPA has no effect on NadR binding activity on the promoter of mafA1 (Fig. 7C), in order to have the same amount of DNA-protein complexes on nadA promoter, more NadR is required in the presence of 4HPA (Fig. 7B), indicating that 4HPA alleviates the binding of NadR on nadA. The same effect of 4HPA on NadR binding activity was also observed on distinct NadR binding sites of the nadA promoter (data not shown). In agreement with this, footprinting experiments on the putA and mafA promoter probes in the presence or absence of 5 mM 4HPA indicated that while NadR protection of the putA binding sites was significantly decreased by the addition of 4HPA to the binding reaction, NadR protection of the mafA binding site remained unaffected by 4HPA (data not shown).

FIG 7.

NadR responds differentially to 4HPA on type I and type II promoter regions. (A) Gel shift analysis of selected NadR targets in the presence of increasing concentrations of 4HPA. Radioactively labeled promoter regions of the indicated genes were incubated with 0 (lane 1) or 36 nM NadR (lanes 2–4) and 4HPA was added at final concentrations of 1 mM (lanes 3) and 5 mM (lanes 4). (B and C) In vitro NadR response to 4HPA on the promoter region of nadA (B) and mafA1 (C) studied by gel shift. The nadA and mafA1 promoter regions were amplified with primer pairs Nad-N1/Nad-B1 and P375-F/P375-652R, respectively. A 40-fmol sample of end-labeled probe was incubated with increasing amounts of NadR protein (nM), either with or without 5 mM 4HPA, as indicated. Free probes are indicated by asterisks, and DNA bound by NadR is indicated by arrowheads.

This analysis suggests that 4HPA affects and decreases the NadR DNA binding affinity only to type I promoters that are induced by 4HPA in vivo, while not having any in vitro effect on NadR binding activity on type II promoters that are corepressed in vivo. This indicates that the nature of the binding site at the type II promoters may be different from those of the type I promoters and that these intrinsic differences of the NadR operators may define the regulation to which they will be subjected.

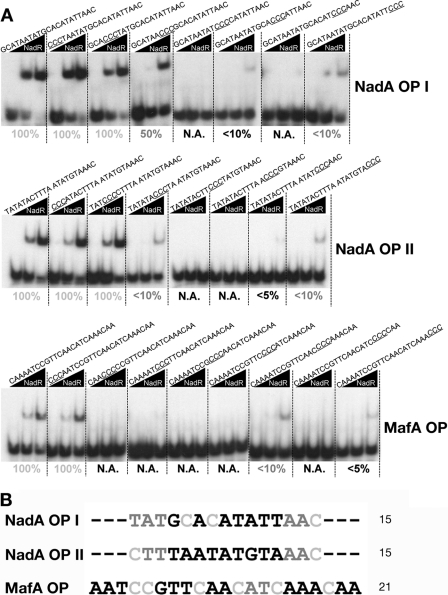

3C scanning mutagenesis reveals extended NadR binding sequence in the operator of mafA promoter region.

In order to elucidate intrinsic differences between single NadR operators at the nadA and mafA1 promoters and the role of nucleotides on NadR binding activity, we generated DNA probes corresponding to the sequences of the high-affinity binding sites of the nadA (OpI and OpII) and mafA1 promoters, identified by DNase I footprint. For each probe we designed a set of mutants, in which three nucleotides were sequentially substituted with CCC. To detect the results of the 3C scanning mutagenesis on NadR binding activity, the probes were submitted to EMSA analysis (Fig. 8A). By identifying the residues whose mutations do not alter the binding of NadR, we defined the minimal binding site (MBS) required for NadR binding on each operator (Fig. 8B). Mutation of nucleotide triplets within the MBS results in either reduced (dark gray residues) or absent (black residues) NadR binding activity. Interestingly, the definition of MBS clearly shows that the operator on the promoter of mafA1 is significantly extended with respect to the high-affinity binding sites in promoter of nadA.

FIG 8.

3C scanning mutagenesis of nadA and mafA single binding sites. (A) DNA probes corresponding to the wild-type NadR-protected sequences from DNAI footprints or to mutated sequences, in which sequential triplicate nucleotides were substituted with CCC, were submitted to gel shift analysis with increasing amounts of NadR purified protein (0, 36, and 360 nM, respectively). The mutated nucleotides are in italics and underlined in the sequences above each gel shift. The NadR binding activity to each probe is reported below each experiment as a percentage of the binding activity shown by NadR on the wild-type sequence. Values given in black are associated with a mutation(s) causing loss or highly compromised NadR binding activity; dark gray values, with less affected NadR binding activity; light gray values, with unaffected NadR binding activity. N.A., not active in binding. (B) The minimal binding sequence (MBS) of each binding site is shown, with nucleotide substitutions essential for binding in black, affecting affinity in dark gray, and with no effect in NadR binding activity in light gray.

These observations suggest a differential mode of NadR binding between the nadA and mafA1 operator, which could be partially responsible for the alternative 4HPA responsive activity of NadR at the two promoters.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we dissect the role of NadR, a member of the MarR family of transcriptional regulators, in N. meningitidis and define its regulon. Here we show that NadR coordinately regulates many genes that all respond to the small signaling molecule 4HPA, a metabolite of amino acid catabolism that is secreted in human saliva. Of the genes with an altered expression profile, NadR had the greatest effect on the nadA gene, which exhibited a >60-fold derepression in the NadR mutant. All other genes in the NadR regulon display much lower expression rate changes, in accordance with the previously described NadR targets (35).

Interestingly, in addition to the NadA adhesin, NadR represses two mafA (multiple adhesin family A) loci of MC58 (NMB0375 and NMB0652), encoding putative adhesins. We have demonstrated that NadR controls the expression of NadA and the MafA1 and MafA2 adhesins in opposing ways in response to the 4HPA inducer molecule. While 4HPA induces NadA expression, it results in corepression of the MafA1 and MafA2 adhesins in a panel of meningococcal strains. Interestingly, human saliva has the same effect of 4HPA on NadA and MafA expression, suggesting that in vitro 4HPA could mimic physiologically relevant signaling molecules in vivo. The presence of differential regulatory responses mediated by one unique regulatory protein suggests that the roles of the NadA and MafA adhesins are mutually exclusive. This regulatory response may indicate an important molecular switch enabling the adaptation of meningococcus to changing niches: as a consequence of the external changing niche-specific signals, a dedicated group of adhesins (i.e., NadA or MafA) relevant for the colonization of that niche will be expressed.

Moreover, the NadR-repressed glycolytic enzyme encoded by the gapA1 gene was recently shown to play a role in adhesion in meningococcus (44) and its homologues in many other systems are well known to function as surface-exposed adhesins (1, 8, 12, 17, 24, 27). Therefore, GapA1 may represent a third adhesin under the control of NadR that will be coexpressed with NadA in response to niche signals.

We have demonstrated that the nadA and other 4HPA-induced promoters (type I) comprise multiple NadR binding sites while the mafA1 and mafA2 promoters (class II) consist of only one binding site for NadR, centered downstream of the promoter sequence. In addition, 4HPA alters the DNA binding activity of NadR at only type I promoters in vitro, without affecting the NadR binding at type II. Therefore, both the architecture of the promoter and the nature of the NadR operators at the promoter may direct the response that NadR will effect to the same signal.

We propose a model (Fig. 9) in which the apo-NadR can bind to and repress nadA and other 4HPA-induced genes (type I) through a looping mechanism, which may result in steric hindrance of RNA polymerase access to the promoter, possibly through dimer-dimer interactions on multiple binding sites. This model has been previously proposed for both the gonococcal farAB promoter (18) and the meningococcal nadA promoter (23) and is supported by the binding at these promoters of the integration host factor (IHF), a histone-like protein which was demonstrated to bend DNA upon binding (42) and could facilitate the interaction between NadR dimers bound at different operators. Following the binding of 4HPA or other biologically relevant signals (Fig. 9, lower panel), the NadR protein can be stabilized in a conformational state which is not able to efficiently bind to type I operators, thus causing the induction of type I genes.

FIG 9.

Model of NadR regulation on type I and type II gene promoters. The promoters of nadA and mafA1 are schematically illustrated and represent the type I and type II promoters, respectively. The top panels show NadR-mediated repression of its different targets. The lower panels show the activity of 4HPA on NadR binding at type I versus type II promoters.

On the other hand, the mafA1 promoter (type II) could be less efficiently repressed by the apo-NadR. However, the 4HPA-bound NadR can still bind at type II binding sites, resulting in a more effective repression of type II genes in vivo. The interaction of a small molecule with a MarR regulator is normally associated with disruption of DNA binding; however, it is not new that ligand binding enhances the DNA binding activity of MarR homologues. The Comamonas testosteroni CbaR is a repressor of the cbaABC operon, which can be induced by 3-chlorobenzoate (30). The binding of 3-hydroxybenzoate and 3-carboxybenzoate increases CbaR DNA binding affinity, thus repressing gene repression (30). In the case of NadR on type II promoters, the 4HPA molecule does not directly increase the affinity of the protein for its binding site (Fig. 7B). Therefore, we suggest that the 4HPA-mediated corepression of type II genes is the result of either a less-efficient promoter clearance in the presence of the binding of the 4HPA-bound NadR or different binding kinetics at type II operators between the apo- and the 4HPA-bound NadR forms.

All these considerations suggest that, rather than different signals, it seems to be the different natures of operators and promoters to decide the kind or regulation performed by the NadR protein on its different targets.

In addition to regulating adhesins, NadR also coordinates many other cellular functions in response to 4HPA or similar signals present in saliva, controlling a generalized adaptation of the meningococcus to the host niche colonization. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that maltodextrins produced in human saliva by α-amylase are crucial for group A streptococcus to successfully infect the oropharynx (36, 37), suggesting that signals present in saliva, other than 4HPA, could be used by bacteria to modulate the gene expression and adapt to the host niche.

NadR is able to repress the expression of various genes implicated in transport of a range of known and unknown substrates, suggesting that it is involved in controlling the substrate-uptake machinery of meningococcus during infection. In addition, it also regulates genes involved in energy metabolic pathways, supporting the idea that it can reroute the metabolism of the cell in response to niche signals. In particular, the ability of NadR of inducing the pathways for amino acid catabolism, such as proline and glutamate utilization, in response to the presence of 4HPA, which is itself an amino acid metabolite, suggests that the environmental availability of amino acid metabolites signals to the cell that amino acids may be abundantly available and NadR adapts the cell metabolism accordingly. Furthermore, NadR links into other regulatory circuits within the cell by affecting expression levels of transcriptional or posttranscriptional regulators, thus indirectly regulating other targets. In addition, NadR binds to its own type I promoter via a 4HPA-dependent mechanism and autoregulates its own expression in a probable negative-feedback loop. Negative autoregulation of FarR has been previously demonstrated in gonococcus (19).

In identifying the NadR regulon and the signals to which it responds, we have gained insights into a coordinated response of the meningococcus which may be relevant during colonization of the oropharynx. While NadR in meningococcus has evolved away from regulating fatty acid resistance, maintaining only residual repressive ability at the farAB promoter, it coordinates a number of seemingly unrelated functions within the cell in response to a niche-specific small molecule signal. It is tempting to speculate that during colonization of the oropharynx, NadR controls the adhesion properties of the cell while also adapting metabolism and other physiologically relevant processes to the competitive host niche.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Maurizio Comanducci and Stefania Bambini for providing meningococcal isolates and Barbara Nesta for providing F62 gonococcal genomic DNA. Strain 5/99 was kindly provided by Dominique A. Caugant. We thank Erika Bartolini for antisera against the MafA proteins and the donation of the mafA1 mafA2 double knockout strain. We thank Alessandro Muzzi for the design of the microarray. We thank Giorgio Corsi for artwork, Kate Seib for critical reading of the manuscript, and Matteo Metruccio and Ana Antunes for helpful discussion.

L.F. is the recipient of a Novartis fellowship from the Ph.D. program in Functional Biology of Molecular and Cellular Systems of the University of Bologna. E.P. is the recipient of a Novartis fellowship from the Ph.D. program in Cellular Biology of the University of Padova.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 November 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Alvarez RA, Blaylock MW, Baseman JB. 2003. Surface localized glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of Mycoplasma genitalium binds mucin. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1417–1425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bentley SD, et al. 2007. Meningococcal genetic variation mechanisms viewed through comparative analysis of serogroup C strain FAM18. PLoS Genet. 3:e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Capecchi B, et al. 2005. Neisseria meningitidis NadA is a new invasin which promotes bacterial adhesion to and penetration into human epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 55:687–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cartwright KA, Stuart JM, Jones DM, Noah ND. 1987. The Stonehouse survey: nasopharyngeal carriage of meningococci and Neisseria lactamica. Epidemiol. Infect. 99:591–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Comanducci M, et al. 2002. NadA, a novel vaccine candidate of Neisseria meningitidis. J. Exp. Med. 195:1445–1454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Deal CD, Krivan HC. 1990. Lacto- and ganglio-series glycolipids are adhesion receptors for Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Biol. Chem. 265:12774–12777 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Delany I, Spohn G, Rappuoli R, Scarlato V. 2001. The Fur repressor controls transcription of iron-activated and -repressed genes in Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1297–1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Egea L, et al. 2007. Role of secreted glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in the infection mechanism of enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: interaction of the extracellular enzyme with human plasminogen and fibrinogen. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39:1190–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ellison DW, Miller VL. 2006. Regulation of virulence by members of the MarR/SlyA family. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fantappiè L, et al. 2011. A novel Hfq-dependent sRNA that is under FNR control and is synthesized in oxygen limitation in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol. 80:507–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Giuliani MM, et al. 2006. A universal vaccine for serogroup B meningococcus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:10834–10839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gozalbo D, et al. 1998. The cell wall-associated glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of Candida albicans is also a fibronectin and laminin binding protein. Infect. Immun. 66:2052–2059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grifantini R, et al. 2002. Previously unrecognized vaccine candidates against group B meningococcus identified by DNA microarrays. Nat. Biotechnol. 20:914–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hanahan D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ieva R, et al. 2005. CrgA is an inducible LysR-type regulator of Neisseria meningitidis, acting both as a repressor and as an activator of gene transcription. J. Bacteriol. 187:3421–3430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ieva R, et al. 2008. OxyR tightly regulates catalase expression in Neisseria meningitidis through both repression and activation mechanisms. Mol. Microbiol. 70:1152–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kinoshita H, et al. 2008. Cell surface Lactobacillus plantarum LA 318 glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) adheres to human colonic mucin. J. Appl. Microbiol. 104:1667–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee EH, Hill SA, Napier R, Shafer WM. 2006. Integration host factor is required for FarR repression of the farAB-encoded efflux pump of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol. Microbiol. 60:1381–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee EH, Rouquette-Loughlin C, Folster JP, Shafer WM. 2003. FarR regulates the farAB-encoded efflux pump of Neisseria gonorrhoeae via an MtrR regulatory mechanism. J. Bacteriol. 185:7145–7152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martin P, Makepeace K, Hill SA, Hood DW, Moxon ER. 2005. Microsatellite instability regulates transcription factor binding and gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:3800–3804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martin P, et al. 2003. Experimentally revised repertoire of putative contingency loci in Neisseria meningitidis strain MC58: evidence for a novel mechanism of phase variation. Mol. Microbiol. 50:245–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maxam AM, Gilbert W. 1977. A new method for sequencing DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 74:560–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Metruccio MM, et al. 2009. A novel phase variation mechanism in the meningococcus driven by a ligand-responsive repressor and differential spacing of distal promoter elements. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Modun B, Morrissey J, Williams P. 2000. The staphylococcal transferrin receptor: a glycolytic enzyme with novel functions. Trends Microbiol. 8:231–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Naumann M, Rudel T, Meyer TF. 1999. Host cell interactions and signalling with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:62–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nichols CE, et al. 2009. The structure of NMB1585, a MarR-family regulator from Neisseria meningitidis. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 65:204–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pancholi V, Fischetti VA. 1992. A major surface protein on group A streptococci is a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase with multiple binding activity. J. Exp. Med. 176:415–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Paruchuri DK, Seifert HS, Ajioka RS, Karlsson KA, So M. 1990. Identification and characterization of a Neisseria gonorrhoeae gene encoding a glycolipid-binding adhesin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:333–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pizza M, et al. 2000. Identification of vaccine candidates against serogroup B meningococcus by whole-genome sequencing. Science 287:1816–1820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Providenti MA, Wyndham RC. 2001. Identification and functional characterization of CbaR, a MarR-like modulator of the cbaABC-encoded chlorobenzoate catabolism pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3530–3541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rouquette-Loughlin CE, Balthazar JT, Hill SA, Shafer WM. 2004. Modulation of the mtrCDE-encoded efflux pump gene complex of Neisseria meningitidis due to a Correia element insertion sequence. Mol. Microbiol. 54:731–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schielke S, et al. 2009. Expression of the meningococcal adhesin NadA is controlled by a transcriptional regulator of the MarR-family. Mol. Microbiol. 72:1054–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schielke S, et al. 2010. The transcriptional repressor FarR is not involved in meningococcal fatty acid resistance mediated by the FarAB efflux pump and dependent on lipopolysaccharide structure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:3160–3169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schielke S, et al. 2011. Characterization of FarR as a highly specialized, growth phase-dependent transcriptional regulator in Neisseria meningitidis. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 301:325–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shelburne SA, III, et al. 2008. Molecular characterization of group A Streptococcus maltodextrin catabolism and its role in pharyngitis. Mol. Microbiol. 69:436–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shelburne SA, III, et al. 2006. Maltodextrin utilization plays a key role in the ability of group A Streptococcus to colonize the oropharynx. Infect. Immun. 74:4605–4614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Siddique A, Buisine N, Chalmers R. 2011. The transposon-like Correia elements encode numerous strong promoters and provide a potential new mechanism for phase variation in the meningococcus. PLoS Genet. 7:e1001277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stephens DS. 1999. Uncloaking the meningococcus: dynamics of carriage and disease. Lancet 353:941–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stromberg N, et al. 1988. Identification of carbohydrate structures that are possible receptors for Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:4902–4906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Studier FW, Moffatt BA. 1986. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J. Mol. Biol. 189:113–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Swinger KK, Rice PA. 2004. IHF and HU: flexible architects of bent DNA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14:28–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Takahama U, Oniki T, Murata H. 2002. The presence of 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid in human saliva and the possibility of its nitration by salivary nitrite in the stomach. FEBS Lett. 518:116–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tunio SA, Oldfield NJ, Ala'Aldeen DA, Wooldridge KG, Turner DP. 2010. The role of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GapA-1) in Neisseria meningitidis adherence to human cells. BMC Microbiol. 10:280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wilkinson SP, Grove A. 2006. Ligand-responsive transcriptional regulation by members of the MarR family of winged helix proteins. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 8:51–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]