Abstract

The taxonomic status and structure of Streptococcus dysgalactiae have been the object of much confusion. Bacteria belonging to this species are usually referred to as Lancefield group C or group G streptococci in clinical settings in spite of the fact that these terms lack precision and prevent recognition of the exact clinical relevance of these bacteria. The purpose of this study was to develop an improved basis for delineation and identification of the individual species of the pyogenic group of streptococci in the clinical microbiology laboratory, with a special focus on S. dysgalactiae. We critically reexamined the genetic relationships of the species S. dysgalactiae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus canis, and Streptococcus equi, which may share Lancefield group antigens, by phylogenetic reconstruction based on multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) and 16S rRNA gene sequences and by emm typing combined with phenotypic characterization. Analysis of concatenated sequences of seven genes previously used for examination of viridans streptococci distinguished robust and coherent clusters. S. dysgalactiae consists of two separate clusters consistent with the two recognized subspecies dysgalactiae and equisimilis. Both taxa share alleles with S. pyogenes in several housekeeping genes, which invalidates identification based on single-locus sequencing. S. dysgalactiae, S. canis, and S. pyogenes constitute a closely related branch within the genus Streptococcus indicative of recent descent from a common ancestor, while S. equi is highly divergent from other species of the pyogenic group streptococci. The results provide an improved basis for identification of clinically important pyogenic group streptococci and explain the overlapping spectrum of infections caused by the species associated with humans.

INTRODUCTION

The genus Streptococcus has been undergoing numerous taxonomic and nomenclature changes and currently includes more than 70 species (http://www.bacterio.cict.fr/s/streptococcus.html). An early classification of streptococci of different pathogenic potentials and host affiliations was made by Rebecca Lancefield (33), who reported that beta-hemolytic streptococci can be defined and differentiated according to a specific carbohydrate “group” antigen, which is an integrated part of the cell wall. Though this may be a reliable method for identification of Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococci) and, with certain exceptions, Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococci), group C, F, and G antigens may be expressed by species of distinct pathogenic potentials and ecological characteristics. The Lancefield antigens C and G are commonly expressed by human isolates of Streptococcus dysgalactiae and by Streptococcus equi and Streptococcus canis, which all belong to the pyogenic group, but also by several species of the anginosus group of streptococci. Yet, together with colony characteristics and hemolytic activity, the Lancefield group antigen is still the most commonly used marker for identification of beta-hemolytic streptococci in the clinical microbiology laboratory (33).

S. dysgalactiae has been the object of much confusion over the years. The name was first proposed for certain distinct bovine streptococci (22), while Streptococcus equisimilis was proposed for human beta-hemolytic streptococci with Lancefield group C antigen (24). Both names, however, lost standing in nomenclature in 1980 when they were not included in the Approved List of Bacterial Names (45). In 1983, the name S. dysgalactiae was revived for alpha-hemolytic bovine streptococci (25). Later, DNA-DNA hybridization data suggested that bovine strains of S. dysgalactiae, S. equisimilis, and so-called “large-colony-forming streptococci” with Lancefield group G and L antigens belonged to a single species, S. dysgalactiae (18). The most recent change in nomenclature was made in 1996, when Vandamme et al. (52), based on chemotaxonomic and phenotypic examination, divided S. dysgalactiae into two subspecies. The name Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis was proposed for human isolates, while Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae was proposed for animal isolates. However, the names S. dysgalactiae and S. equisimilis are still used in clinical settings, and it has been argued that it would be practical to maintain the two taxa as separate species (29). According to the proposal of Vandamme and coworkers (52), S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis contains human isolates of beta-hemolytic, large-colony-forming streptococci with Lancefield group C or G antigen. However, occasional isolates of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis with Lancefield group A antigen or with alpha-hemolysis on sheep blood agar have been described (7, 11, 21). Occasionally, beta-hemolytic animal strains of S. dysgalactiae are also referred to as S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (41, 50).

S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis colonizes the human upper respiratory, gastrointestinal, and female genital tracts and was previously considered nonpathogenic. However, more recent studies revealed that S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis overlaps with the infection spectrum of S. pyogenes, including localized infections such as tonsillitis and superficial skin infections (2, 12, 16, 51) and severe invasive infections such as arthritis, osteomyelitis, pleuropneumonia, peritonitis, intra-abdominal and epidural abscesses, meningitis, endocarditis, puerperal septicemia, neonatal infections, necrotizing fasciitis, myositis, and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, as well as the nonsuppurative sequelae and rheumatic fever (2, 4, 9, 12, 13, 26, 27, 36–38, 44). A proportional increase in human infections caused by S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis has been reported since the late 1970s and early 1980s, and studies have indicated that the disease burden of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis approximates or even exceeds that of S. pyogenes in some areas (10, 13). In Denmark, streptococci with Lancefield group C or G antigens are nearly as frequently isolated from blood cultures as is S. pyogenes (http://www.ssi.dk/Aktuelt/Nyhedsbreve/EPI-NYT/2011/). The overlap in infection spectrum between S. pyogenes and S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis is correlated with a significant overlap in the virulence properties of the two species, usually explained by horizontal gene transfer from S. pyogenes to S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (20, 42, 48). This includes the M-protein gene, which is of central importance in the pathogenesis of S. pyogenes infections and used for epidemiologic typing (emm typing) of this species (3, 6, 19). S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis is also emm typeable, but no clear relationship between emm type and genetic relatedness has been established in S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, as is the case for S. pyogenes. Based on multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA), significant interspecies recombination between S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. pyogenes was reported (1, 34).

The purpose of this study was to develop an improved basis for identification of the individual species of the pyogenic group of streptococci in the clinical microbiology laboratory and for understanding their clinical significance and reasons for current changes in their epidemiology. We critically reexamined the genetic relationships of the species S. dysgalactiae, S. pyogenes, S. canis, and S. equi, which may share Lancefield group antigens, using phylogenetic reconstruction based on multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) (34) and 16S rRNA gene sequences and emm typing, combined with phenotypic characterization. To obtain a comprehensive view of the population structure of S. dysgalactiae, we included isolates of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae, which usually is considered to be exclusively associated with animals. The results add to the phylogenetic picture of the genus, provide an improved basis for identification of clinically important species, and explain the overlap in the spectrum of infections caused by S. pyogenes and S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

A total of 95 Streptococcus strains were included in the study. (i) Fifty strains were human clinical isolates of large-colony-forming (>1 mm) beta-hemolytic Lancefield group C and G streptococci isolated during 2006 and 2007 at Viborg Hospital, Denmark. Twenty-three of these were isolated from blood, while the majority of the remaining isolates were from patients with tonsillitis. (ii) Twenty-six isolates of S. dysgalactiae came from the Culture Collection of the University of Gothenburg, Sweden (CCUG). (iii) Thirteen strains of S. equi representing all three subspecies and (iv) six S. canis isolates from CCUG were included because these two species share Lancefield group antigen with S. dysgalactiae and because of their potential involvement in zoonotic infections. A full list of the strains and their origins is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of isolates included in the study

| Strain | Identification based on MLSA (subcluster) | CCUG classification | Source | Lancefield antigen | emm type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCUG 27658 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae | Pig | C | NTa |

| CCUG 27659 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae | Pig | C | NT |

| CCUG 27664 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae | Horse | C | NT |

| CCUG 27665 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae | Dog | L | stL2764.0 |

| CCUG 28112 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (1) | S. equisimilis | Horse | C | NT |

| CCUG 28113 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae | Pig | C | NT |

| CCUG 28114 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (1) | S. equisimilis | Horse | C | stC210.0 |

| CCUG 28115 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae | Horse | C | NT |

| CCUG 28116 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae | Dog | C | NT |

| CCUG 28117 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (1) | S. equisimilis | Dog | C | NT |

| CCUG 48477 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae | Dog | C | stL1929.0 |

| CCUG 7977A | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae | Dog | L | NT |

| CCUG 11663 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (2) | S. dysgalactiae | Cow | C | NT |

| CCUG 27301T | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (2) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae | Cow | C | NT |

| CCUG 27439 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (2) | S. dysgalactiae | Cow | C | NT |

| SK 1397 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (2) | Human, blood | G | stC74a.0 | |

| SK 1400 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (2) | Human, blood | G | stG485.0 | |

| SK 1425 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (2) | Human, blood | G | stG485.0 | |

| SK 1406 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (2) | Human, blood | G | stG485.0 | |

| SK 1407 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (2) | Human, blood | G | stG480.0 | |

| SK 1408 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (2) | Human, blood | G | stG480.0 | |

| SK 1420 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (2) | Human, blood | G | stC74a.0 | |

| SK 1421 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (2) | Human, blood | G | stG652.1 | |

| CCUG 45841 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (2) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis | Human, throat | A | stG840.0 |

| CCUG 45898 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (2) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis | Human, throat | A | stG840.0 |

| SK 1361 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stC839.0 | |

| SK 1328 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Perianal | C | stG62647.0 | |

| SK 1332 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stC839.0 | |

| SK 1381 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stC839.0 | |

| SK 1382 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | emm57.4 | |

| SK 1354 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | emm57.3 | |

| SK 1353 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stG62647.0 | |

| SK 1370 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stC839.0 | |

| SK 1339 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | emm57.4 | |

| SK 1376 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stC839.0 | |

| SK 1351 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stG62647.0 | |

| SK 1352 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stG62647.0 | |

| SK 1371 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | emm57.4 | |

| SK 1398 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Urine | G | stG480.0 | |

| SK 1394 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, blood | C | stG643.1 | |

| SK 1409 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, blood | G | stG480.0 | |

| SK 1413 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, blood | G | stG480.0 | |

| SK 1405 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, blood | G | stG480.0 | |

| SK 1391 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, blood | C | stG652.0 | |

| SK 1392 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, blood | C | stG643.1 | |

| CCUG 18742 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis | Human | C | stC839.2 |

| CCUG 32017 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis | Human | C | stC839.0 |

| CCUG 33645 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis | Human, blood | G | stG6792.0 |

| CCUG 48101 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis | Human, throat | C | stC839.0 |

| CCUG 502 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis | Human | G | stG643.0 |

| SK 1386 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, impetigo | G | stG166b | |

| SK 1387 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, impetigo | G | stG166b | |

| SK 1367 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stG653.0 | |

| SK 1336 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stC36.4 | |

| SK 1346 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | emm57.4 | |

| SK 1333 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stC36.4 | |

| SK 1365 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stC36.4 | |

| SK 1329 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stC36.4 | |

| SK 1338 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stC36.0 | |

| SK 1378 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stC36.4 | |

| SK 1379 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stC1400 | |

| SK 1410 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | G | stG643.0 | |

| SK 1411 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | G | stG643.0 | |

| SK 1372 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stC36.4 | |

| SK 1373 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, throat | C | stC36.4 | |

| SK 1412 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, blood | G | stG840.0 | |

| SK 1404 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, blood | G | stG6.4 | |

| SK 1389 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, blood | G | stG6.1 | |

| SK 1423 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, blood | G | stG245.0 | |

| SK 1415 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, blood | G | stG507.1 | |

| SK 1418 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, blood | G | stG643.0 | |

| SK 1419 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | Human, blood | G | stG6.4 | |

| CCUG 36637T | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis | Human | C | st652.2 |

| CCUG 4211 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis | Human, vagina | C | stG652.2 |

| CCUG 50442 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | S. constellatus | Human, vagina | C | stC36.0 |

| CCUG 7216 | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (1) | S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis | Human, blood | G | stG6.1 |

| SK 1388 | S. equi | Human, blood | C | —b | |

| CCUG 23010A | S. equi | S. equi subsp. equi | Horse | C | — |

| CCUG 23255T | S. equi | S. equi subsp. equi | Unknown animal source | C | — |

| CCUG 23256T | S. equi | S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus | Cow | C | — |

| CCUG 23257 | S. equi | S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus | Unknown animal source | C | — |

| CCUG 27366 | S. equi | S. equi subsp. equi | Horse | C | — |

| CCUG 27662 | S. equi | S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus | Cow | C | — |

| CCUG 27663 | S. equi | S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus | Horse | C | — |

| CCUG 27363 | S. equi | S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus | Horse | C | — |

| CCUG 47520T | S. equi | S. equi subsp. ruminatorum | Sheep | C | — |

| CCUG 49310 | S. equi | S. equi subsp. ruminatorum | Sheep | C | — |

| CCUG 49311 | S. equi | S. equi subsp. ruminatorum | Sheep | C | — |

| CCUG 54867 | S. equi | S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus | Human, cerebrospinal fluid | C | — |

| CCUG 27481 | S. canis | S. canis | Cow | G | — |

| CCUG 27492 | S. canis | S. canis | Dog | G | — |

| CCUG 27493 | S. canis | S. canis | Cat | G | — |

| CCUG 27496 | S. canis | S. canis | Dog | G | — |

| CCUG 27661T | S. canis | S. canis | Cow | G | — |

| CCUG 37321 | S. canis | S. canis | Cow | G | — |

NT, not typeable.

—, isolate was not screened for the presence of emm types.

Phenotypic characterization.

Phenotypic analyses were carried out on all S. dysgalactiae isolates and on all S. equi isolates, as they are frequently isolated from zoonotic human infections. Colony size and beta-hemolysis were determined on 5% horse blood agar plates (Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark) after incubation in an anaerobic chamber for 24 h. All isolates with no hemolysis on blood agar were incubated for 24 h on chocolate agar plates for detection of alpha-hemolysis (liberation of hydrogen peroxide) observed as green zones around colonies due to oxidation of hemoglobin. Growth patterns in Todd-Hewitt broth were observed after 24 h of incubation in 5% CO2-enriched air. Growth was considered either flocculent or diffuse.

The Lancefield group antigen was identified by Streptex (Oxoid A/S, Denmark), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Hyaluronidase activity was demonstrated as described by Smith and Willett (46). Acid production from sorbitol and salicin, hydrolysis of esculin- and d-arginine, and production of acetoin from glucose (Voges-Proskauer test) were detected as described by Kilian et al. (30), with the exception that the presence of esculin- and d-arginine hydrolysis were detected after anaerobic growth for 7 days, as some isolates did not grow in these substrates under aerobic conditions. The presence of β-glucuronidase, α-galactosidase, neuraminidase, β-d-glucosidase, β-galactosidase (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside [ONPG]), N-acetyl-β-galactosaminidase, and β-fucosidase was detected using synthetic fluorogenic substrates as described by Whiley et al. (54). Pyrrolidonyl arylamidase (PYR) activity was tested using the O.B.I.S.-PYR test kit (Oxoid A/S, Denmark), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Bacitracin susceptibility was tested on blood agar using sterile paper discs containing 0.04 units of bacitracin (Oxoid A/S, Denmark) and overnight incubation at 37°C.

DNA extraction.

DNA was extracted from isolates grown on blood agar for 24 h in a CO2-enriched environment. Using a 1-μl inoculation loop, colonies were collected from the agar plate and suspended in PCR-grade water. A volume of 20 μl of this suspension was mixed with 80 μl of 0.05 M NaOH and incubated for 45 min at 60°C. After incubation, 9.2 μl of 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7, was added. This crude DNA preparation was diluted 100 times for PCR analysis.

PCR and sequencing of housekeeping genes.

An MLSA scheme originally developed by Bishop et al. (8) based on sequences of seven housekeeping genes to study the phylogenetic relationships and to enable identification of isolates of the genus Streptococcus with a particular focus on mitis group streptococci was used. Fragments of the housekeeping genes map, pfl, ppaC, pyk, rpoB, sodA, and tuf were amplified by PCR and sequenced using degenerate primers as described previously (8): map-up, 5′-GCWGACTCWTGTTGGGCWTATGC; map-dn, 5′-TTARTAAGTTCYTTCTTCDCCTTG; pfl-up, 5′-AACGTTGCTTACTCTAAACAAACTGG; pfl-dn, 5′-ACTTCRTGGAAGACACGTTGWGTC; ppaC-up, 5′-GACCAYAATGAATTYCARCAATC; ppaC-dn, 5′-TGAGGNACMACTTGTTTSTTACG; pyk-up, 5′-GCGGTWGAAWTCCGTGGTG; pyk-dn, 5′-GCAAGWGCTGGGAAAGGAAT; rpoβ-up, 5′-AARYTIGGMCCTGAAGAAAT; rpoβ-dn, 5′-TGIARTTTRTCATCAACCATGTG; sodA-up, 5′-TRCAYCATGAYAARCACCAT; sodA-dn, 5′-ARRTARTAMGCRTGYTCCCARACRTC; tuf-up, 5′-GTTGAAATGGAAATCCGTGACC; tuf-dn, 5′-GTTGAAGAATGGAGTGTGACG. Briefly, 1 μl of each primer (10 μM), 10 μl of DNA, and 13 μl of H2O were added to Illustra PuReTaq Ready-To-Go PCR beads (GE Healthcare, Brøndby, Denmark). The annealing temperature was 55°C for map, pfl, and ppaC and 50°C for pyk, rpoB, sodA, and tuf with 30 cycles of amplification for both annealing temperatures. Purified PCR products were sequenced from both directions at the Beijing Genomics Institute, China, using standard procedures.

Data analysis.

Sequences of the seven housekeeping genes were edited, aligned, and subjected to phylogenetic analysis using MEGA5 (49). Trimmed sequences from the work of Bishop et al. (8) were used as template for trimming and alignment. After alignment, the trimmed sequences for each of the housekeeping genes as well as a concatenated sequence of all seven genes were subjected to phylogenetic analysis using the minimum evolution algorithm. Bootstrap tests were performed with 500 replicates for minimum evolution trees based on each of the seven housekeeping genes and on the concatenated sequence. The sequences of 420 Streptococcus strains from the study by Bishop et al. (8), including 17 strains of S. pyogenes, were included in the phylogenetic analysis. In addition, sequences of the corresponding housekeeping genes from the following genomes were extracted and included in the analysis: S. pyogenes MGAS 10750 (NC_008024), S. pyogenes MGAS 2096 (NC_008023), S. pyogenes MGAS 10270 (NC_008022), S. pyogenes MGAS 9429 (NC_008021), S. pyogenes MGAS 5005 (NC_007297), S. pyogenes MGAS 6180 (NC_007296), S. pyogenes MGAS 10394 (NC_006086), S. pyogenes MGAS 6180 (CP000056.1), S. pyogenes MGAS 10394 (NC_006086), S. pyogenes ATCC 10782 (NZ_AEEO00000000), S. pyogenes SSI-1 (NC_004606), S. pyogenes MGAS 315 (NC_004070), S. pyogenes MGAS 8232 (NC_003485), S. pyogenes M1 (NC_002737), S. pyogenes Manfredo (NC_009332), Streptococcus equi subsp. equi 4047 (NC_012471), Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus MGCS 10565 (NC_011134), S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis ATCC 12394 (CP002215.1), S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis GGS 124 (NC_012891), S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae ATCC 27957 (CM001076). For a more detailed analysis of genetic relationships, we extracted sequences of 82 housekeeping genes from the same genomes plus Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis SK1250 (AFUL01000001.1), and Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis SK1249 (AFIN00000000.1).

Genetic distances were calculated in MEGA5 using the Kimura 2-parameter model. The average frequencies of synonymous substitutions per potential synonymous site (ds) and nonsynonymous substitutions per potential nonsynonymous site (dn) were calculated by the method of Nei and Gojobori in MEGA5.

16S rRNA gene analyses.

16S rRNA gene sequences were amplified and sequenced using the universal eubacterial primers 27f, 5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′, and 1492r, 5′-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′. The reaction mix consisted of 3 μl of each primer (10 μM), 5 μl of DNA, and 14 μl of H2O added to Illustra PuReTaq Ready-To-Go PCR beads (GE Healthcare, Brøndby, Denmark). The annealing temperature was 55°C, and 30 cycles were run. Purified PCR products were sequenced on both strands using the same primers at GATC-Biotech, Konstanz, Germany, using standard procedures. A total of 1,268 bases were included for phylogenetic analysis. In addition, 16S rRNA sequences of S. dysgalactiae isolates were downloaded from the Ribosomal Database Project (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/hierarchy/hb_intro.jsp) (17), to cover the maximal phylogenetic diversity within S. dysgalactiae. Furthermore, 16S rRNA gene sequences from type strains of other pyogenic group streptococci were included in the phylogenetic analysis.

S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis specific PCR assay.

To test if the MLSA clustering of S. dysgalactiae was consistent with the accepted subdivision of the two recognized subspecies, a PCR assay described as specific for S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis was applied (35). The PCR assay was run as a duplex PCR with S. dysgalactiae species-specific 16S rRNA primers and performed as described by Preziuso et al. (41).

emm typing.

emm typing was performed as described by Beall et al. (5, 6). Each sequence was subjected to a homology search (Streptococci Group A Subtyping Request Form, BLAST 2.0 server [http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/strep/strepblast.htm]), and the emm type was determined.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences determined in this study were submitted to GenBank with the accession numbers indicated: map, JN632385 to JN632479; pfl, JN632290 to JN632384; ppaC, JN632195 to JN632289; pyk, JN632100 to JN632194; rpoβ, JN632005 to JN632099; sodA, JN631910 to JN632004; tuf, JN631815 to JN631909; 16S, JN639380 to JN639445.

RESULTS

MLSA.

The seven primer pairs, initially developed for amplification of housekeeping genes from viridans streptococci (mitis, anginosus, mutans, and salivarius groups), successfully amplified the relevant sequences from all isolates included in this study. The trimmed sequences were all of same length, as is the case for viridans streptococci.

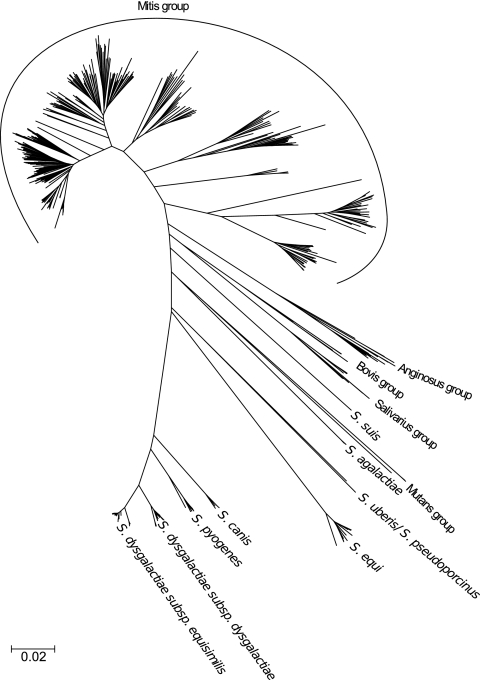

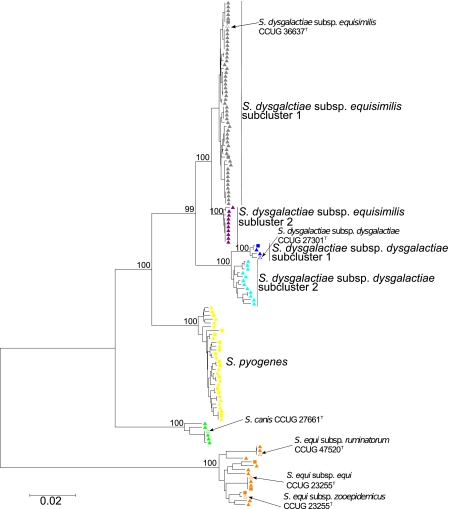

A minimum evolution tree based on concatenated sequences determined in this study combined with sequences of a selection of Streptococcus species represented in the MLSA viridans streptococcus database (http://viridans.emlsa.net/) is shown in Fig. 1. The tree shows considerably more genetic homogeneity within clusters of pyogenic group streptococci than within clusters constituting commensal species such as Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus oralis, and Streptococcus infantis. The detailed structure of S. dysgalactiae and its relationships to S. pyogenes, S. canis, and S. equi are shown in Fig. 2. In addition to the sequences generated in this study, the analysis included sequences retrieved from genome-sequenced strains of the respective species. Both trees illustrate that the species S. dysgalactiae, S. pyogenes, and S. canis are closely related and that they form a separate clade within the pyogenic group, while S. equi is only distantly related.

Fig 1.

Radial minimum evolution tree based on concatenated sequences of seven housekeeping genes that shows the phylogenetic positions of the species groups within the Streptococcus genus. The tree was constructed from concatenated sequences of the 95 strains from this study combined with sequences of 420 strains, primarily from the mitis group, from the study by Bishop et al. (8), and sequences extracted from the whole genomes of 40 Streptococcus strains.

Fig 2.

Minimum evolution tree based on concatenated sequences of seven housekeeping genes and showing the position of the 112 strains of S. dysgalactiae, S. equi, S. canis, and S. pyogenes. The strains within the defined clusters are color labeled: S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis subcluster 1, gray; S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis subcluster 2, purple; S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae subcluster 1, blue; S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae subcluster 2, turquoise; S. pyogenes, yellow; S. canis, green; S. equi subspecies, orange. Open symbols, arrows, and designations indicate the positions on the tree of the type strains. S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae are both divided into two subclusters. Triangles indicate isolates from this study, while squares indicate sequences extracted from whole-genome sequences. Bootstrap values for major branches are shown.

Whereas isolates clustering with the type strains of S. canis and S. pyogenes clearly constitute monophyletic clusters, the S. dysgalactiae cluster divides into a cluster of human S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates and a cluster of animal S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates (Fig. 2). These two clusters include the type strains of the subspecies S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae, respectively, thus supporting these two distinct taxa. Both S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae and S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis further segregated into two subclusters. The clustering of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates is in agreement with their hemolytic activity. While all strains in subcluster 1, including the type strain of the species, were alpha-hemolytic, strains clustering in subcluster 2 were beta-hemolytic. Whether this difference between alpha-hemolytic and beta-hemolytic S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae strains applies to the entire population of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae requires a more extensive examination of isolates from different animal hosts. Notably, three isolates from subgroup 2 are erroneously listed as S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis in the CCUG database, presumably based on their beta-hemolytic activity (Table 1).

These findings indicate that beta-hemolytic isolates of animal origin currently assigned to S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis belong to S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae and that S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis is most likely exclusively associated with humans, while S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae is associated with certain animal species. To further evaluate this, the previously published PCR assay (34, 40) for the specific detection of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis was applied to the strains. Interestingly, only the four beta-hemolytic isolates of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae from horses were positive in the assay. No other strain of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae and none of the human isolates of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis were positive in the assay.

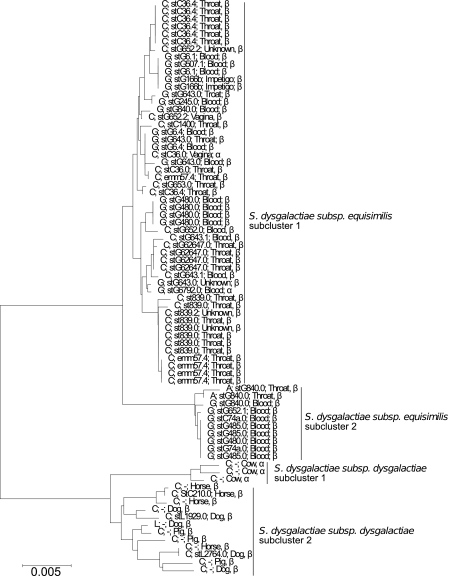

Among S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis strains, subcluster 1 included both Lancefield group C and G isolates and the type strain of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (CCUG 36637T) (Fig. 2 and 3), while subcluster 2 included eight strains with Lancefield group G antigen and two isolates with Lancefield group A antigen. With the exception of a single strain (CCUG 50442, stC36, vagina), each lineage in the tree was associated with a particular group antigen. Apart from the two group A isolates, all strains from subcluster 2 of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae were from invasive infections (isolated from blood) (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Minimum evolution tree of concatenated sequences of the seven housekeeping genes of the S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates with relation to Lancefield antigen, emm type, isolation site, and hemolysis. Bootstrap values for major branches are shown.

Strains of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae were of Lancefield group C or group L, but a clear association between phylogenetic lineage and group antigen was not discernible.

Single-locus phylogenetic analysis.

The topology of the tree based on concatenated sequences of the seven housekeeping genes showed well-separated clusters supported by significant bootstrap values (99 to 100%) (Fig. 2). However, none of the individual housekeeping genes reproduced the same clustering supported by significant bootstrap values (see Fig. S1a to g in the supplemental material). Strikingly, the clusters of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae, S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, and S. pyogenes showed several examples of overlapping. This is especially evident in the trees based on the sodA and tuf genes, where S. pyogenes shares alleles with S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae, respectively. Likewise, one strain of S. pyogenes clusters with S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis in the tree based on pyk gene sequences.

Even though strains of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and subsp. dysgalactiae cluster closely together in trees based on some genes, no identical alleles were observed in the two subspecies. The separation of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae into two subclusters was evident in trees based on most of the individual genes. In contrast, the subclustering of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis based on concatenated sequences was a result of differences in a single gene, rpoB, with subcluster 2 having an allele that is closely related to those of S. pyogenes.

Analysis of various combinations of housekeeping genes showed that any pair of the three genes ppaC, pfl, and map was able to separate the species and subspecies of S. dysgalactiae in clusters supported by significant bootstrap values. However, S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis subcluster 2, which is distinct solely because of a single very distant rpoB allele, was detected in its correct position only in analyses based on concatenated sequences of a minimum of rpoB, pfl, ppaC, and map. The combination of rpoB, sodA, pyk, and tuf identified S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis subcluster 2 as a subcluster of the S. pyogenes cluster. Concatenated sequences of five or more genes always yielded tree topologies concordant with the seven-gene tree.

Sequence characteristics of housekeeping genes.

Characteristics for concatemers and the individual genes for the S. dysgalactiae isolates are shown in Table 2. The mean genetic distance for the concatemers was 0.0056 and 0.011 for S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae and S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, respectively. The number of different alleles ranged from three in the tuf and pfl genes to 13 in the rpoB gene for S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae and from five in the tuf and pfl genes to 11 in the ppaC gene for S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis. The ratios (dn/ds) of nonsynonymous (dn) to synonymous (ds) substitutions were well below 1, indicating purification as normally observed for housekeeping genes.

Table 2.

Sequence characteristics of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae

| Locus |

S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis |

S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean genetic distance between isolates (SE) | No. of alleles | dn/ds ratio | Mean genetic distance between isolates (SE) | No. of alleles | dn/ds ratio | |

| Concatemer | 0.006 (0.0009) | 29 | 0.03 | 0.01 (0.001) | 15 | 0.06 |

| map | 0.004 (0.002) | 5 | —a | 0.02 (0.006) | 7 | 0.03 |

| pfl | 0.001 (0.0005) | 3 | — | 0.01 (0.007) | 5 | 0.08 |

| ppaC | 0.0004 (0.0002) | 5 | 0.04 | 0.001 (0.003) | 11 | 0.2 |

| pyk | 0.005 (0.002) | 10 | 0.02 | 0.009 (0.002) | 7 | 0.009 |

| rpoB | 0.02 (0.004) | 13 | 0.03 | 0.008 (0.002) | 7 | — |

| sodA | 0.005 (0.003) | 9 | 0.2 | 0.01 (0.005) | 8 | 0.09 |

| tuf | 0.0001 (0.0001) | 3 | — | 0.002 (0.001) | 5 | — |

—, either dn or ds was zero.

Although only 15 isolates of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae compared to 61 isolates of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis were analyzed, it appears from the genetic distance and the number of distinct alleles of the genes for the two subspecies (Table 2) that S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis is a more genetically conserved taxon than S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae. Whether this reflects a true difference or is a consequence of the selection of isolates included in this study has to be evaluated.

Overall genetic relationship between species.

Table 3 shows the genetic distance between the individual taxa examined in the study. As shown by the distances given in Table 3 and reflected in Fig. 2, the two subclusters of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis are nearly as closely related to S. pyogenes as they are to S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae. The species S. canis, S. pyogenes, and S. dysgalactiae form a separate clade within the pyogenic group of streptococci, whereas S. equi isolates clustered together in a deeply branching cluster far from the other pyogenic species included in the study. Among the S. equi subspecies, only Streptococcus equi subsp. ruminatorum was clearly distinct from representatives of the two other subspecies of the species.

Table 3.

Mean genetic distances between clusters defined by concatenated sequences of seven housekeeping genesa

| Cluster | Mean distance between clusters |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | |

| S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis subcluster 1 (a) | 0.003 | 0.007 (0.004) | 0.008 | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.02 | 0.04 (0.05) | |

| S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis subcluster 2 (b) | 0.01 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | |

| S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae subcluster 1 (c) | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.04 | 0.004 | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.02 | 0.04 (0.05) | |

| S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae subcluster 2 (d) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | |

| S. pyogenes (e) | 0.06 (0.12) | 0.05 | 0.08 (0.14) | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.04 (0.05) | |

| S. canis (f) | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.04 | |

| S. equi (g) | 0.2 (0.34) | 0.2 | 0.2 (0.34) | 0.2 | 0.2 (0.34) | 0.2 | |

Standard errors are shown in the upper triangle. Values in parentheses are genetic distances based on 82 housekeeping genes extracted from genomes of 15 S. pyogenes strains, four S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis strains (including SK1249 and SK1250 from this study), one S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae strain, two S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus strains, and one S. equi subsp. equi strain. The strains are listed in Materials and Methods.

To further analyze the genetic relationships between the two subspecies of S. dysgalactiae and S. pyogenes based on a more comprehensive sample of the genome, we extracted sequences of 82 (28,835 bp) housekeeping genes common to and distributed over the entire genomes from the genome database at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/genome) of 15 S. pyogenes strains, one strain of S. equi subsp. equi, two strains of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus, four strains of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, and one strain of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae. The genetic distances are shown in Table 3.

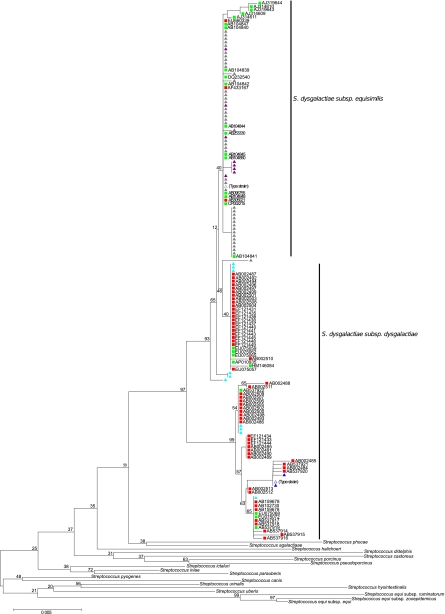

16S rRNA gene sequences.

Figure 4 shows a phylogenetic tree of the S. dysgalactiae strains constructed from 16S rRNA sequences determined in this study and combined with sequences extracted from the rRNA Database Project 10. S. dysgalactiae isolates clustered into two main clusters. While one cluster included only isolates of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae, the other cluster contained both S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates. Several sequences of isolates that were from animals but were classified as S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis in the Ribosomal Database Project 10 clustered with the S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates, illustrating the current problems associated with correct identification of these taxa. (These inconsistencies were reported to the curator of the RDP-II database.)

Fig. 4.

Minimum evolution tree of the 16S rRNA gene sequences from the 76 strains of S. dysgalactiae from this study as well as 79 sequences from both subspecies of S. dysgalactiae extracted from the Ribosomal Database Project 10 (RDP10) database. Sequences from this study are shown as triangles: S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis subcluster 1, gray; S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis subcluster 2, purple; S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae subcluster 1, blue; S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae subcluster 2, turquoise. Sequences from GenBank assigned as S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis are shown as green squares, while sequences assigned to S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae are shown as red squares. Bootstrap values for major branches are shown.

It is remarkable that the close phylogenetic relationship between S. dysgalactiae and S. pyogenes revealed by the MLSA is not reflected by a distance-based tree of the 16S rRNA sequences, where both S. dysgalactiae and S. pyogenes are more closely related to other Streptococcus species of the pyogenic group than to each other.

emm typing.

All 76 strains assigned to both S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae were screened for the presence of the emm gene. In the emm-specific PCR, all strains of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis produced a single band. Two different sizes were observed, one was approximately 1,200 bp and the other was approximately 1,400 bp, and all amplicons resulted in a readable sequence. Among the 15 strains of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae, eight beta-hemolytic strains yielded a band with a size of approximately 1,200 bp with the initial PCR, but only three isolates gave readable sequences with the sequencing primer. A total of 21 different emm types were found. Some emm types were correlated with specific alleles of the concatenated sequences like stG485, stC839, and stG62647 (Table 4 and Fig. 3). Furthermore, an association between invasive isolates and noninvasive isolates and emm type was observed for some emm types. Thus, 17 strains of stC36 and stC839 were all throat isolates while the 10 strains of stG480 and stG6 were exclusively blood isolates (Fig. 3). Three emm types were associated with more than one Lancefield antigen. A novel emm type was discovered in one strain assigned to S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae subcluster 1 and was designated stC210.

Table 4.

List of emm types found in the 76 strains of S. dysgalactiae included in this study

| emm type | No. of associated alleles | No. of isolates | Isolation site |

|---|---|---|---|

| stL2764a | 1 | 1 | Dog |

| stL1929a | 1 | 1 | Dog |

| stC210a,b | 1 | 1 | Horse |

| stG485 | 1 | 3 | Blood |

| stC74a | 1 | 2 | Blood |

| stG480 | 2 | 6 | Blood |

| stG840 | 3 | 3 | Blood/throat |

| stG652 | 3 | 3 | Blood/vagina |

| stC36 | 3 | 9 | Throat |

| stC839 | 1 | 8 | Throat |

| emm57 | 2 | 5 | Throat |

| stG62647 | 2 | 4 | Throat |

| stG6 | 2 | 4 | Blood |

| stG643 | 6 | 6 | Throat/blood |

| stG166b | 1 | 2 | Impetigo |

| stG6792 | 1 | 1 | Blood |

| st652 | 1 | 1 | Unknown |

| stC1400 | 1 | 1 | Throat |

| stG245 | 1 | 1 | Blood |

| stG507 | 1 | 1 | Blood |

| stG653 | 1 | 1 | Throat |

emm types are found in S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae.

stC210 is a novel emm type.

Phenotypic analysis.

The phenotypic characteristics of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae, and S. equi are summarized in Table 5. All strains of S. dysgalactiae were PYR negative, rendering the PYR test useful for differentiation between S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, including strains with the group A antigen, and S. pyogenes. Susceptibility to bacitracin has been widely used to identify S. pyogenes. However, several strains of S. dysgalactiae were bacitracin susceptible, including one of the Lancefield group A S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis strains, indicating that this test is unreliable for identification of S. pyogenes.

Table 5.

Phenotypic characteristics of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae, and S. equi

| Characteristic | % of isolates positive |

Resulta |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis |

S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae |

S. equi (n = 13) | S. canis | S. pyogenes | |||

| Subcluster 1 (n = 51) | Subcluster 2 (n = 10) | Subcluster 1 (n = 12) | Subcluster 2 (n = 3) | ||||

| Lancefield group antigen | |||||||

| A | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | − | + |

| C | 65 | 0 | 83 | 100 | 100 | − | − |

| G | 35 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | − |

| L | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | − | − |

| Growth in TH mediumb | |||||||

| Flocculent | 88 | 100 | 100 | 67 | 54 | ND | ND |

| Diffuse | 12 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 46 | ND | ND |

| Colony diam >1 mm | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 92 | + | + |

| β-hemolysis | 96 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | + | + |

| α-hemolysis | 4 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | − | − |

| Hyaluronidase | 98 | 100 | 92 | 100 | 0 | − | + |

| Salicin | 90 | 10 | 50 | 0 | 77 | + | + |

| Sorbitol | 2 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 100 | − | − |

| Esculin hydrolysis | 69 | 50 | 25 | 0 | 77 | + | d |

| Arginine hydrolysis | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | + | + |

| Voges-Proskauer (VP) | 10 | 10 | 8 | 0 | 8 | − | − |

| β-Glucuronidase | 73 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | d | d |

| α-Galactosidase | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | d | − |

| β-d-Glucosidase | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 | ND | − |

| Neuraminidase | 0 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 54 | ND | d |

| β-Galactosidase (ONPG) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | + | − |

| N-Acetyl-β-galactosaminidase | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | ND | ND |

| β-Fucosidase | 78 | 90 | 50 | 0 | 0 | ND | ND |

| Pyrrolidonyl arylamidase (PYR) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | − | + |

| Bacitracin susceptibility | 14 | 20 | 17 | 0 | 23 | − | + |

Data are from Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (55); d, different strains give different reactions; ND, not determined.

TH, Todd-Hewitt broth.

In general, none of the tested biochemical reactions could distinguish between S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae or between the four subclusters identified by MLSA. Some interesting tendencies, however, were observed. No Lancefield group C isolates were found in subcluster 2 of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, while all beta-hemolytic and all alpha-hemolytic isolates of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae were found in subclusters 1 and 2, respectively. Furthermore, most of the isolates in subcluster 1 of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis were positive for salicin fermentation while only 1 out of 10 isolates from subcluster 2 was positive. S. equi strains were all positive in the sorbitol fermentation test, which differentiated them from S. dysgalactiae isolates, of which only 2 of 76 isolates were positive. No differences in phenotypic characteristics were observed between the three subspecies of S. equi (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Correct identification of pyogenic streptococci is a crucial prerequisite for understanding the pathogenic potential of the individual species of this clinically important group of bacteria and the implications of and reasons for the current changes in infection epidemiology. The current use of Lancefield grouping as an almost exclusive identification tool is clearly not satisfactory. In this study, we demonstrated the value of the application of an MLSA scheme initially developed for viridans streptococci (8) on pyogenic group streptococci. All the isolates and reference strains included in the study yielded useful sequences, and by analysis of concatenated sequences of all seven genes, we were able to distinguish robust and coherent clusters. Results of this study and our parallel work on the anginosus group (A. Jensen and M. Kilian, unpublished data) further emphasize the potential of the MLSA scheme for identification of isolates and for detection and delineation of new species. The results illustrate the problems of current identification procedures by showing several misclassified strains from recognized culture collections and in the rRNA project database. Incorrect labeling of sequences in the latter database has important implications because of its extensive use in the annotation of sequence data generated in molecular studies of complex microbiotas in human and animals.

Our results also demonstrate that identification of Streptococcus species using a one-gene approach is problematic. The genes rpoB and sodA have been suggested as the genes of choice for identifying streptococci to species level (23, 40). However, we show that S. pyogenes and S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis share alleles of the sodA gene and that at least one lineage of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis has a sodA allele that is more closely related to S. pyogenes than to other alleles found among S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis strains. These results, which are analogous to observations reported for mitis group streptococci (28, 31), also emphasize the problems of evaluating identification schemes with only a few isolates from each species.

After many years of debate and reclassifications, the current definition of the species S. dysgalactiae is that it consists of two subspecies, S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae and S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, of which the first is associated with certain animal species while the latter is associated with humans (52). One case of zoonosis with S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae has been reported from Japan, where a chef was assumed to be infected by a fish strain of the species (32). Moreover, the name S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis is used in the veterinary literature for beta-hemolytic isolates of S. dysgalactiae found in animals (41, 50). According to our results, based on analysis of concatemers of seven housekeeping genes, isolates of S. dysgalactiae of animal origin and of human origin are clearly distinct and constitute two clusters that correspond to the two subspecies dysgalactiae and equisimilis (Fig. 3). Thus, S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae includes both alpha- and beta-hemolytic lineages of animal origin. Interestingly, the three alpha-hemolytic isolates of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae included in this study constituted a separate subcluster within the subspecies according to analysis of both housekeeping and 16S rRNA gene sequences. Whether this reflects a true phylogenetic difference between beta-hemolytic and alpha-hemolytic lineages of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae or is a consequence of the small number of isolates included in this study needs to be investigated.

Also, S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis includes bacteria with both types of hemolysis, but two alpha-hemolytic isolates were otherwise indistinguishable from the remaining isolates of the subspecies.

Our findings provide several examples of strains previously misidentified presumably due to primary emphasis on hemolytic activity: of the two alpha-hemolytic isolates of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, one is listed as Streptococcus constellatus, while three of the beta-hemolytic isolates of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae are listed as S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis in the CCUG database. The potential problem of identification based on hemolytic activity was previously noted in a study by Dierksen and Tagg (21), in which they showed that isolates of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis with alpha-hemolytic activity on sheep blood are common and may be overlooked in the clinical laboratory. To further evaluate if S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis is found only in humans, we applied a PCR assay based on the streptokinase gene, which was reported as an S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis-specific test (35). Interestingly, the assay was positive only for S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates from horses, suggesting that the assay may be specific for S. dysgalactiae isolates from horses rather than for S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis. This conclusion is supported by the fact that the assay is based on a streptokinase gene sequence of a horse isolate with very little homology with the streptokinase gene sequence of human isolates (14).

Previous studies of the population structure of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis used a multilocus sequence typing (MLST) scheme originally developed for S. pyogenes (1, 34). In agreement with our study based on other genes, both previous studies showed a close relationship between S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. pyogenes and examples of closely related alleles or even identical alleles previously assumed to be due to interspecies homologous recombination. In our study, related alleles and allele sharing were observed between the two taxa in the genes rpoB, tuf, pyk, and especially sodA. Indeed, when translated to amino acid sequences, only sequences of Map and PpaC could distinguish S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. pyogenes (data not shown). Likewise, S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae and S. pyogenes showed very closely related alleles in the pyk and rpoB genes and identical alleles of the tuf gene. The very close genetic relationship between the two latter taxa was also evident from our analysis of a comprehensive sampling of housekeeping genes throughout the genome in agreement with recently reported results based on presence or absence of genes in complete genomes of both subspecies of S. dysgalactiae and S. pyogenes (48). Interestingly, this close relationship is not reflected in the phylogenetic tree generated from 16S rRNA gene sequences, which suggests a close relationship of S. dysgalactiae to Streptococcus agalactiae and Streptococcus phocae rather than to S. pyogenes (Fig. 4). This indicates that 16S rRNA sequences are inadequate for determining finer details of the interspecies relationships within the genus Streptococcus.

The 12 isolates of S. equi were initially included because of the Lancefield antigen sharing with S. dysgalactiae and the zoonosis caused by S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus. We found a very weak, if any, separation between the two subspecies equi and zooepidemicus, and some subspecies zooepidemicus isolates were more closely related to subspecies equi than to other subspecies zooepidemicus isolates. This is in agreement with the findings of Webb et al. (53), who found that some isolates of subspecies equi had the same ST as isolates of subspecies zooepidemicus. These findings suggest that the separation between the two subspecies should be reconsidered. In contrast, S. equi subsp. ruminatorum is clearly distinct from the two other subspecies.

As demonstrated in Table 5, phenotypic identification of S. dysgalactiae and its subspecies remains problematic, as is the case for many mitis group streptococci (28). Detection of Lancefield group antigen is helpful but may not allow unequivocal separation from S. pyogenes. However, a negative PYR test may distinguish Lancefield group A S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis strains from PYR-positive S. pyogenes strains. Our findings clearly demonstrated that the bacitracin susceptibility test is unreliable for differentiation of these species. Several of the Lancefield group antigens (C, G, and A) are also expressed by members of the distantly related anginosus group, although in experienced hands such streptococci may be differentiated by colony size and smell. Exact identification requires sequencing of multiple housekeeping genes, whereas identification based on single loci, including 16S rRNA genes, is problematic. Although currently not realistic in the clinical setting, the use of the MLSA scheme described by Bishop et al. (8) and used in this study offers an accurate means of identification, which eventually will provide a unique picture of the genus Streptococcus and its species. Of practical use for the clinical laboratory, we found that for the species of interest a phylogenetic tree based on concatenated sequences of the two housekeeping genes ppaC and pfl was concordant with the tree based on concatemers of seven housekeeping genes. In contrast, separate or concatenated sequences of rpoB, sodA, tuf, and pyk were unable to separate isolates of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis subcluster 2 from S. pyogenes. Alternatively, the combination of sodA sequencing, used by many clinical laboratories, and the PYR test appears to be suitable for species identification of S. dysgalactiae, including both subspecies, and S. pyogenes.

Virulence factors shared by S. dysgalactiae and S. pyogenes include the antiphagocytic M protein. The emm gene was detected in all strains of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, in agreement with previous observations (34, 39, 43, 47). An association between noninvasive and invasive isolates and certain emm types was observed. Thus, stG485, stG480, and stG6 were strongly associated with invasive infections. However, in the study reported by Sunaoshi et al. (47) only stG480 was associated with invasive infections. In the study reported by Pinho et al. (39), none of these three emm types was associated with invasive isolates. In contrast, the observed association of stC839 with noninvasive infection is in agreement with two previous reports (39, 47). More isolates must be analyzed to draw a definitive conclusion as to the association between emm type and disease, as has been shown in S. pyogenes.

Three emm types were found in S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae: one new emm type, designated stC210, and two emm types previously found in S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates of Lancefield group L. This is to our knowledge the first report of emm types found in S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae and shows that the emm gene is present in the genome of beta-hemolytic strains of the species. In accordance with the study reported by Rato et al. (42), who tested only alpha-hemolytic S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates, we were unable to amplify the emm gene from alpha-hemolytic strains of this subspecies. Whether this reflects a lack of the gene in alpha-hemolytic strains of subsp. dysgalactiae or is due to sequence divergence in the target sequence remains to be shown.

Ahmad et al. (1) found that isolates of S. pyogenes with the same emm type were often highly related, whereas S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates with identical or closely similar STs often exhibited multiple unrelated emm types, which differed from S. pyogenes. McMillan et al. (34) found that more than half (60%) of the S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates studied had a unique combination of emm type, ST, and Lancefield antigen and therefore concluded that this subspecies shows a very high level of genetic diversity. However, according to our phylogenetic tree-based concatenated sequences of the seven housekeeping genes, S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae appear very homogenous compared to most other Streptococcus species, although it is unlikely that our collection of strains represents the full genetic diversity in the two subspecies.

DNA-DNA hybridization has shown more than 70% similarity between the two subspecies of S. dysgalactiae, which is the reason for the proposal to give them subspecies status (52). However, in our study, the mean sequence distance between the two subspecies did not strikingly exceed that between S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. pyogenes (Table 3). It would be impractical to combine the two subspecies of S. dysgalactiae and S. pyogenes in one species. The alternative solution, which takes the distinct habitats of the two current subspecies of S. dysgalactiae into consideration, would be to recognize the two as separate species, which is in agreement with the traditions in many clinical microbiology laboratories. However, a study including a more comprehensive collection of isolates from the whole spectrum of potential habitats is needed to draw any definitive conclusions regarding the delineation of the two taxa.

The distinct habitats of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (animals) and S. pyogenes and S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (humans) may suggest that the observed allele relationships are due to recombination events that took place before habitat separation, or simply reflect their common ancestry, which is supported also by the fact that most of the isolates of S. pyogenes and S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (in the sodA gene) and isolates of S. pyogenes and S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (in the tuf gene) have related alleles with minor diversification due to accumulation of point mutations over time. We favor the latter scenario, which also offers an adequate explanation of the sharing of multiple virulence genes and overlapping of clinical significance of the human taxa of S. dysgalactiae and S. pyogenes. The prevalence and clinical consequences of infections due to S. pyogenes have always been fluctuating (15), presumably as a result of the contributions to virulence of mobile genetic elements carried by phages. The virulence of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis is likely to be governed by similar genetic events, which conceivably explain the current relative increase in the proportions of infections due to this taxon.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a stipend from the Faculty of Health Sciences, Aarhus University, to A.J. and by a project grant to M.K. from the Danish Medical Research Council (271-08-0808).

Clinical isolates used in the study were kindly provided by Jørgen Prag, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Viborg Hospital, Denmark.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 November 2011

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ahmad Y, et al. 2009. Genetic relationships deduced from emm and multilocus sequence typing of invasive Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. canis recovered from isolates collected in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:2046–2054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barnham M, Kerby J, Chandler RS, Millar MR. 1989. Group C streptococci in human infection: a study of 308 isolates with clinical correlations. Epidemiol. Infect. 102:379–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barroso V, et al. 2009. Identification of active variants of PARF in human pathogenic group C and group G streptococci leads to an amended description of its consensus motif. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 299:547–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barson WJ. 1986. Group C streptococcal osteomyelitis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 6:346–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beall B, Facklam R, Hoenes T, Schwartz B. 1997. Survey of emm gene sequences and T-antigen types from systemic Streptococcus pyogenes infection isolates collected in San Francisco, California; Atlanta, Georgia; and Connecticut in 1994 and 1995. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1231–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beall B, Facklam R, Thompson T. 1996. Sequencing emm-specific PCR products for routine and accurate typing of group A streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:953–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bert F, Lambert-Zechovsky N. 1997. Analysis of a case of recurrent bacteraemia due to group A Streptococcus equisimilis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Infection 25:250–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bishop CJ, et al. 2009. Assigning strains to bacterial species via the internet. BMC Biol. 7:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bradley SF, Gordon JJ, Baumgartner DD, Marasco WA, Kauffman CA. 1991. Group C streptococcal bacteremia: analysis of 88 cases. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13:270–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bramhachari PV, et al. 2010. Disease burden due to Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (group G and C streptococcus) is higher than that due to Streptococcus pyogenes among Mumbai school children. J. Med. Microbiol. 59:220–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brandt CM, Haase G, Schnitzler N, Zbinden R, Lutticken R. 1999. Characterization of blood culture isolates of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis possessing Lancefield's group A antigen. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:4194–4197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brandt CM, Spellerberg B. 2009. Human infections due to Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:766–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Broyles LN, et al. 2009. Population-based study of invasive disease due to beta-hemolytic streptococci of groups other than A and B. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:706–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caballero AR, Lottenberg R, Johnston KH. 1999. Cloning, expression, sequence analysis, and characterization of streptokinases secreted by porcine and equine isolates of Streptococcus equisimilis. Infect. Immun. 67:6478–6486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carapetis JR, Steer AC, Mulholland EK, Weber M. 2005. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 5:685–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cimolai N, Morrison BJ, MacCulloch L, Smith DF, Hlady J. 1991. Beta-haemolytic non-group A streptococci and pharyngitis: a case-control study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 150:776–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cole JR, et al. 2009. The Ribosomal Database Project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D141–D145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Collins MD, Farrow JAE, Katic V, Kandler O. 1984. Taxonomic studies on streptococci of serological group E, group P, group U, and group V—description of Streptococcus porcinus sp. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 5:402–413 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cunningham MW. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:470–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davies MR, et al. 2007. Virulence profiling of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis isolated from infected humans reveals 2 distinct genetic lineages that do not segregate with their phenotypes or propensity to cause diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:1442–1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dierksen KP, Tagg JR. 2000. Haemolysin-deficient variants of Streptococcus pyogenes and S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis may be overlooked as aetiological agents of pharyngitis. J. Med. Microbiol. 49:811–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Diernhofer K. 1932. Aesulinbouillon as Hilfmittel für die Differenzierung von Euter- and Milchstreptokokken bei Masseuntersuchungen. Milchwirtenschaftlige Forsch. 13:368–374 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Drancourt M, Roux V, Fournier PE, Raoult D. 2004. rpoB gene sequence-based identification of aerobic Gram-positive cocci of the genera Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Gemella, Abiotrophia, and Granulicatella. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:497–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Frost WD, Engelbrecht MA. 1940. The streptococci: their descriptions, classification, and distribution, with special reference to those in milk. Willdof Book Company, Madison, WI [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garvie EI, Farrow JAE, Bramley AJ. 1983. Streptococcus dysgalactiae (Diernhofer) nom. rev. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 33:404–405 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Haidan A, et al. 2000. Pharyngeal carriage of group C and group G streptococci and acute rheumatic fever in an Aboriginal population. Lancet 356:1167–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hashikawa S, et al. 2004. Characterization of group C and G streptococcal strains that cause streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:186–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hoshino T, Fujiwara T, Kilian M. 2005. Use of phylogenetic and phenotypic analyses to identify nonhemolytic streptococci isolated from bacteremic patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:6073–6085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kilian M. 2005. Streptococcus and Lactobacillus, p 833–881 In Borriello SP, Murray PR, Funke C. (ed), Topley and Wilson microbiology and microbial infection, vol. 2 Hodder Arnold, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kilian M, Mikkelsen L, Henrichsen J. 1989. Taxonomic study of viridans streptococci—description of Streptococcus gordonii sp. nov. and emended descriptions of Streptococcus sanguis (White and Niven 1946), Streptococcus oralis (Bridge and Sneath 1982), and Streptococcus mitis (Andrewes and Horder 1906). Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 39:471–484 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kilian M, et al. 2008. Evolution of Streptococcus pneumoniae and its close commensal relatives. PLoS One 3:e2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koh TH, et al. 2009. Streptococcal cellulitis following preparation of fresh raw seafood. Zoonoses Public Health 56:206–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lancefield RC. 1933. A serological differentiation of human and other groups of hemolytic streptococci. J. Exp. Med. 57:571–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McMillan DJ, et al. 2010. Population genetics of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis reveals widely dispersed clones and extensive recombination. PLoS One 5:e11741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nakamura M, Honda K, Tun Z, Ogura Y, Matoba R. 2001. Application of in situ PCR to diagnose pneumonia in medico-legal autopsy cases. Leg. Med. (Tokyo) 3:127–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nielsen SV, Kolmos HJ. 1993. Bacteremia due to different groups of beta-hemolytic streptococci—a 2-year survey and presentation of a case of recurring infection due to Streptococcus equisimilis. Infection 21:358–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nitta AT, Kuritzkes DR. 1991. Pyomyositis due to group C streptococci in a patient with AIDS. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13:1254–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ortel TL, Kallianos J, Gallis HA. 1990. Group C streptococcal arthritis: case report and review. Rev. Infect. Dis. 12:829–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pinho MD, Melo-Cristino J, Ramirez M. 2006. Clonal relationships between invasive and noninvasive Lancefield group C and G streptococci and emm-specific differences in invasiveness. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:841–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Poyart C, Quesne G, Coulon S, Berche P, Trieu-Cuot P. 1998. Identification of streptococci to species level by sequencing the gene encoding the manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:41–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Preziuso S, Laus F, Tejeda AR, Valente C, Cuteri V. 2010. Detection of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis in equine nasopharyngeal swabs by PCR. J. Vet. Sci. 11:67–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rato MG, et al. 2011. Virulence gene pool detected in bovine group C Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae by use of a group A Streptococcus pyogenes virulence microarray. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:2470–2479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Reissmann S, et al. 2010. Contribution of Streptococcus anginosus to infections caused by groups C and G streptococci, southern India. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:656–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sing A, Trebesius K, Heesemann J. 2001. Diagnosis of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis (group C streptococci) associated with deep soft tissue infections using fluorescent in situ hybridization. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. 20:146–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. 1980. Approved lists of bacterial names. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 30:225–420 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Smith RF, Willett NP. 1968. Rapid plate method for screening hyaluronidase and chondroitin sulfatase-producing microorganisms. Appl. Microbiol. 16:1434–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sunaoshi K, et al. 2010. Molecular emm genotyping and antibiotic susceptibility of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolated from invasive and non-invasive infections. J. Med. Microbiol. 59:82–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Suzuki H, et al. 2011. Comparative genomic analysis of the Streptococcus dysgalactiae species group: gene content, molecular adaptation, and promoter evolution. Genome Biol. Evol. 3:168–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tamura K, et al. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Timoney JF. 2004. The pathogenic equine streptococci. Vet. Res. 35:397–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Turner JC, Hayden FG, Lobo MC, Ramirez CE, Murren D. 1997. Epidemiologic evidence for Lancefield group C beta-hemolytic streptococci as a cause of exudative pharyngitis in college students. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vandamme P, Pot B, Falsen E, Kersters K, Devriese LA. 1996. Taxonomic study of Lancefield streptococcal groups C, G, and L (Streptococcus dysgalactiae) and proposal of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis subsp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46:774–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Webb K, et al. 2008. Development of an unambiguous and discriminatory multilocus sequence typing scheme for the Streptococcus zooepidemicus group. Microbiology 154:3016–3024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Whiley RA, Fraser H, Hardie JM, Beighton D. 1990. Phenotypic differentiation of Streptococcus intermedius, Streptococcus constellatus, and Streptococcus anginosus strains within the “Streptococcus milleri group.” J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:1497–1501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Whiley RA, Hardie JM. 2009. Family VI. Streptococcaceae, p 655–735 InDe Vos P, et al. (ed), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 2nd ed, vol 3 The Firmicutes Springer, Heidelberg, Germany [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.