Abstract

The immune system responds to pathogens by a variety of pattern recognition molecules such as the Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which promote recognition of dangerous foreign pathogens. However, recent evidence indicates that normal intestinal microbiota might also positively influence immune responses, and protect against the development of inflammatory diseases1,2. One of these elements may be short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which are produced by fermentation of dietary fibre by intestinal microbiota. A feature of human ulcerative colitis and other colitic diseases is a change in ‘healthy’ microbiota such as Bifidobacterium and Bacteriodes3, and a concurrent reduction in SCFAs4. Moreover, increased intake of fermentable dietary fibre, or SCFAs, seems to be clinically beneficial in the treatment of colitis5-9. SCFAs bind the G-protein-coupled receptor 43 (GPR43, also known as FFAR2)10,11, and here we show that SCFA–GPR43 interactions profoundly affect inflammatory responses. Stimulation of GPR43 by SCFAs was necessary for the normal resolution of certain inflammatory responses, because GPR43-deficient (Gpr43−/−) mice showed exacerbated or unresolving inflammation in models of colitis, arthritis and asthma. This seemed to relate to increased production of inflammatory mediators by Gpr43−/− immune cells, and increased immune cell recruitment. Germ-free mice, which are devoid of bacteria and express little or no SCFAs, showed a similar dysregulation of certain inflammatory responses. GPR43 binding of SCFAs potentially provides a molecular link between diet, gastrointestinal bacterial metabolism, and immune and inflammatory responses.

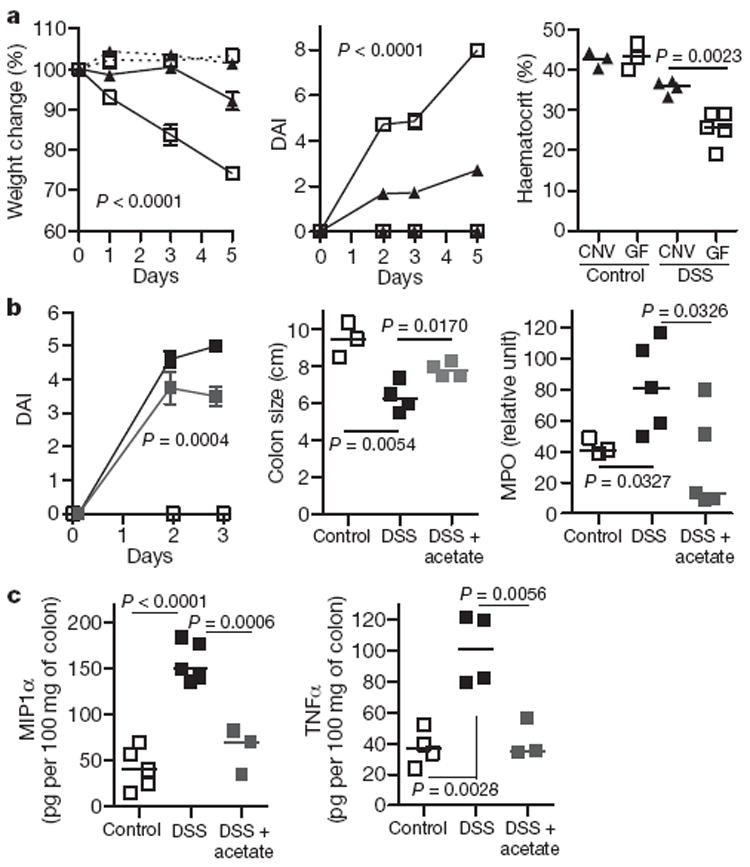

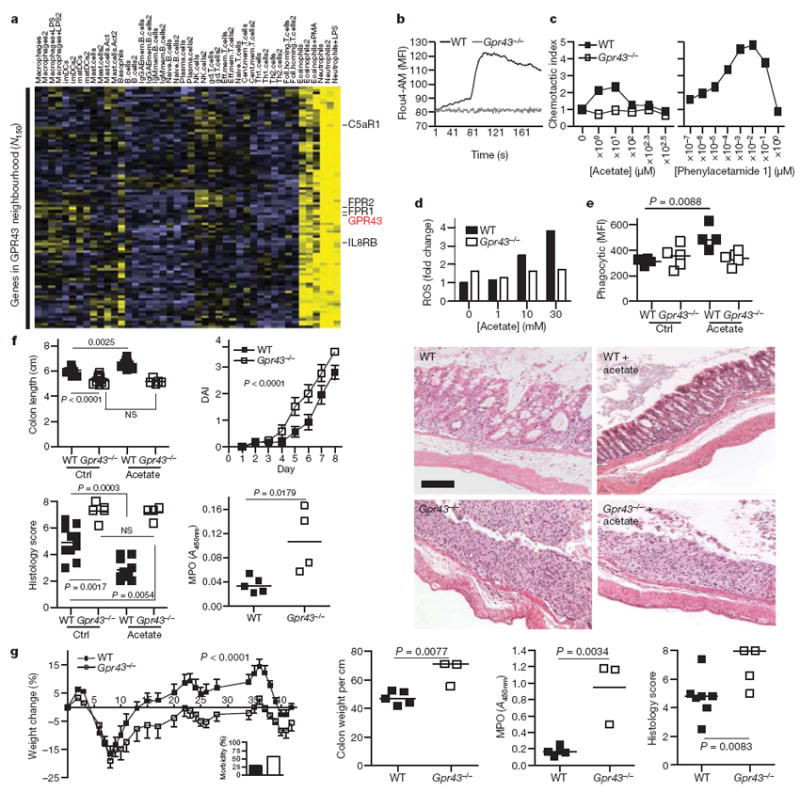

Recent evidence suggests that products of intestinal microbiota might positively influence inflammatory disease pathogenesis1,2. To identify factors produced by bacteria that might be beneficial to host immune responses, we induced colitis chemically by adding dextran sulphate sodium (DSS) to the drinking water of germ-free mice. The absence of bacteria from these mice, and the consequences this had on immune responses, resulted in significantly worse colonic inflammation, compared to conventionally raised (CNV) mice. Germ-free mice treated with DSS had decreased weight, an increased daily activity index (DAI; a combined measure of weight loss, rectal bleeding and stool consistency) and a decreased haematocrit (Fig. 1a). Germ-free mice re-colonized with gut microbiota, by gavaging with CNV faeces, showed a marked reduction in inflammation (Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating that the exacerbated response related to lack of bacterial colonisation of the gut. Products of bacteria that have been reported to show anti-inflammatory properties include SCFAs, which are produced by colonic bacteria after fermentation of dietary fibre. Bacteria of the Bacteroidetes phylum produce high levels of acetate and propionate, whereas bacteria of the Firmicutes phylum produce high amounts of butyrate12. Germ-free mice do not produce SCFAs owing to a lack of enteric microbes13. Treatment of germ-free mice with 150 mM acetate in the drinking water markedly improved disease indices, with an increase in colon length, decreased DAI and levels of the inflammatory mediator myeloperoxidase (MPO) (Fig. 1b), and decreased levels of TNFα and inflammatory MIP1α (also known as CCL3) (Fig. 1c). SCFAs have a well-characterized anti-inflammatory effect, on both colonic epithelium and immune cells14-17. Recently, SCFAs, particularly acetate (C2) and propionate (C3), have been found to bind and activate the G-protein-coupled receptor GPR43 (refs 10, 11). Using an extensive data set of human and mouse immune cell transcription profiles18 we found that transcripts for human GPR43 and mouse Gpr43 exhibited enhanced expression in neutrophils and eosinophils (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2). Using nearest-neighbour correlation analysis we found that GPR43 gene expression was closely regulated with receptors important for innate immunity, such as Toll-like receptors (TLR2 and TLR4), formyl peptide receptors (FPR1 and FPR2), IL8RB (also known as CXCR2) and C5aR (Fig. 2a). We constructed protein interaction networks for genes co-regulated with GPR43, and, using a molecular complex detection and a graph-theory-based clustering (MCODE)algorithm19, we identified densely connected local sub-network clusters, revealing modules associated with apoptosis and innate immunity-related processes (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 1. Exacerbated colitis in germ-free mice is ameliorated by acetate.

a, Germ-free (open squares) and CNV (closed triangles) mice were given DSS colitis (4%), n = 7 (experimental groups). Dashed lines, control mice; solid lines, DSS-treated mice. The percentage weight change (left), DAI (middle) and haematocrit (right) were measured. b, Germ-free mice were fed acetate (grey squares; 150 mM; n = 3) in the drinking water or water only (black squares; n = 5), 5 days before and during DSS administration. Control fed denotes no DSS (open squares). Daily activity score (left), colon length (middle) and colonic MPO (right) were determined. c, MIP1α and TNFα levels in acetate-fed mice. Data are median ± s.e.m., representative of two independent experiments.

Figure 2. GPR43 expression and role in inflammatory responses.

a, Immune expression signature of genes encoding cellular receptors across a large panel of leukocyte subsets. Clustering of receptor genes exhibiting enriched expression in neutrophils and eosinophils reveals GPR43, along with other receptors important for innate immunity and chemoattractant-induced responses. Correlation analysis across a wider set of genes in this immune panel identified a rank-ordered list of the top 150 genes (N150) in the co-expression neighbourhood of GPR43. b–e, Comparison of wild-type (WT) and Gpr43−/− bone marrow neutrophils with respect to acetate-induced Ca2+ flux (b; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity), chemotaxis (c, left panel), ROS production (d), and phagocytosis of fluorescently labelled S. aureus (e). The right panel of c shows the GPR43 synthetic agonist phenylacetamide 1 in human neutrophil chemotaxis. f, DSS colitis (2.5% (w/v)) in wild-type and Gpr43−/− mice, fed with acetate or control water (Ctrl). Shown are colon length, the DAI, histology score and colon MPO levels. NS, not significant. The far right panels show representative histological sections from wild-type or Gpr43−/− mice as indicated (scale bar, 50 μm). g, Chronic DSS-induced colitis (n = 7 per group, median ± s.e.m.). The inset shows the percentage morbidity. Shown are the percentage change in weight, colon weight per cm of colon, colonic MPO, and histological score, for wild-type and Gpr43−/− mice.

To demonstrate that GPR43 was the relevant receptor for SCFA effects on immune cells, we sourced Gpr43−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 4), and found that T- and B-cell numbers were normal, and their blood neutrophil numbers were in the normal range (not shown). Acetate induced a robust calcium flux in mouse neutrophils (as well as in human neutrophils and eosinophils, not shown), but not in neutrophils from Gpr43−/− mice (Fig. 2b), indicating that GPR43 is the sole functional receptor for SCFAs on neutrophils. GPR43 has previously been reported to act as a chemoattractant receptor for acetate11, and we found that neutrophils from wild-type, but not Gpr43−/− mice, responded chemotactically to acetate, but only at very high concentrations (~100–1,000 μM), and with a relatively low chemotactic index (Fig. 2c). This may relate to the low affinity of GPR43 for SCFAs20, the high concentrations of SCFAs normally present in tissues (0.1–10 mM in serum, and 200 mM in the colon)11,13, and the need for chemoattractant receptors to sense a gradient. However, a recently reported synthetic agonist specific for human GPR43 with > 100-fold potency over SCFAs20 was much more robust in chemotaxis assays (Fig. 2c). In neutrophils from wild-type mice, but not Gpr43−/− mice, SCFAs induced release of ROS and increased phagocytic activity (Fig. 2d, e) similar to activities reported for certain other chemoattractant receptors.

The characteristic expression pattern of GPR43 to cell types involved in innate immunity and inflammation, and the GPR43-dependent effects of SCFA neutrophil function suggested that GPR43 may be the relevant receptor on immune cells for the regulation of inflammatory responses by SCFAs. We induced colitis by adding DSS to the drinking water of Gpr43−/− and wild-type litter-mate mice. In the acute phase (7 days), Gpr43−/− mice showed a marked increased in their inflammatory response, compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 2f), including a reduced colon length, and an increased DAI, more severe inflammation by histological analysis and increased MPO activity in the colon, indicating increased neutrophil infiltration/activation (Fig. 2f). We next determined whether acetate protected against colitis in the acute DSS model, in a GPR43-dependent manner. Mice fed 200 mM acetate in their drinking water showed a substantial decrease in inflammation, as judged by longer colon length, a reduced DAI, reduced inflammatory infiltrate and less tissue damage, when compared to wild-type mice not fed acetate (Fig. 2f). Notably, this protection occurred by acetate binding to GPR43, because acetate had no beneficial effect in Gpr43−/− mice (Fig. 2f).

In a chronic model of DSS-induced colitis, Gpr43−/− mice showed greater morbidity (at day 8, Fig. 2g, inset), and a marked reduction in the ability to regain weight compared to wild-type littermates (Fig. 2g). By day 42, Gpr43−/− mice showed reduced colon length, increased colon histology score, as well as increased MPO levels in the colon. In a T-cell-dependent model of colitis, the TNBS (trinitrobenzoic sulphonic acid)-induced model, Gpr43−/− mice also had more severe disease with decreased colon length and increased colon histological scores (Supplementary Fig. 5). CD44+IL17+ T cells in the mesenteric lymph nodes in this model were increased in Gpr43−/− mice, as were transcripts for IL17A, IL6, IL1β, IFNγ and CCL2 in colon tissue (Supplementary Fig. 5).

GPR43 is also expressed on colonic epithelium, and SCFAs affect several functions of these cells including proliferation, and epithelial barrier function21 and butyrate is a major source of energy for colonocytes. We determined the contribution of immune and non-immune cells to the colitis phenotype we observed in Gpr43−/− mice by using bone marrow chimaeras (Supplementary Fig. 6). After 7 weeks of bone marrow reconstitution, colitis was induced by DSS in the drinking water. Wild-type mice reconstituted with Gpr43−/− bone marrow showed a similar exacerbated inflammatory response in the colon, compared to Gpr43−/− mice receiving Gpr43−/− bone marrow, demonstrating that immune cells were largely responsible for the phenotype observed in Gpr43−/− mice.

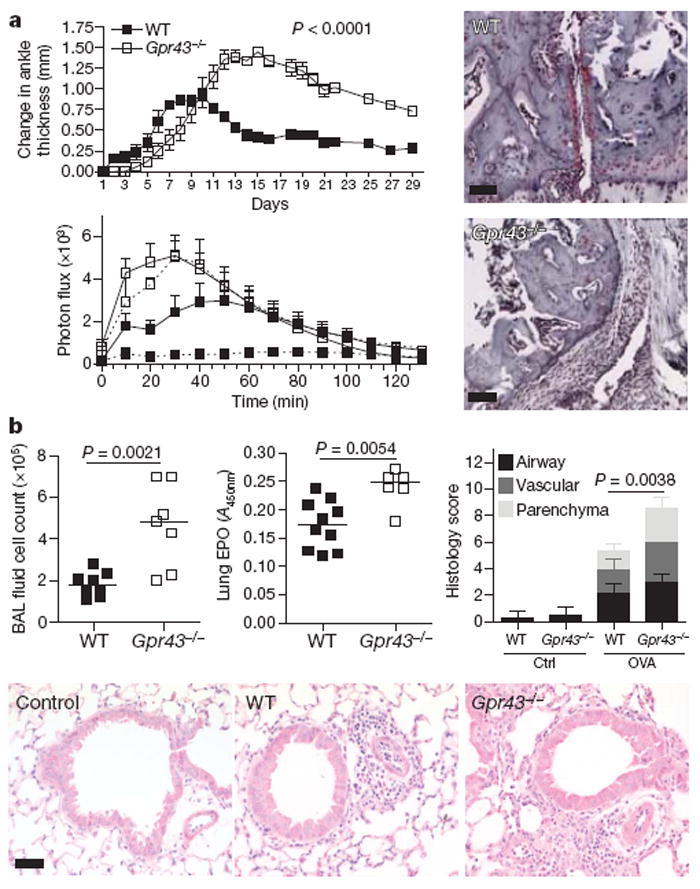

SCFA levels in the colon can be high, particularly after ingestion of large amounts of fibre, and SCFAs are rapidly absorbed and distribute systemically through the blood22. We therefore assessed peripheral inflammatory responses in Gpr43−/− mice using the K/BxN serum-induced model of inflammatory arthritis and an ovalbumin (OVA)-induced model of allergic airway inflammation. In the inflammatory arthritis model Gpr43−/− mice showed a slight delay in the onset of symptoms, but by day 11 inflammation in Gpr43−/− mice was markedly more severe than in wild-type littermates, clinically and histologically, and did not resolve over the 28 days of study (Fig. 3a). Gpr43−/− mice showed increased levels of MPO production by peripheral blood cells (Fig. 3a). Acetate in the drinking water 1 week before, and during, the induction of inflammatory arthritis reduced inflammation (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Germ-free mice given K/BxN serum also showed increased inflammation and a much slower resolution of inflammation when compared to CNV housed mice (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Gpr43−/− mice also showed more severe inflammation compared with wild-type littermates in an acute allergic airway inflammation model, with increased numbers of cells in the broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, as well as greater levels of eosinophil peroxide and inflammatory cells in the lung tissue (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. Inflammatory arthritis and allergic airway disease and GPR43 deficiency.

a, Inflammatory arthritis (K/BxN serum injection on day 0 and 2) in Gpr43−/− mice (n = 5) versus wild-type littermates (n ≥ 3). Scores shown are mean ± s.e.m. for each time point, representative of three independent experiments. Wild-type mice are represented with closed squares, Gpr43−/− mice with open squares, controls with dashed lines, and arthritic mice with solid lines. Change in ankle thickness (top) and measurement of MPO in the peripheral blood (bottom) showed that both naive and arthritic Gpr43−/− mice had higher MPO production when stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; bottom), indicating greater neutrophil activation (P < 0.001 Gpr43−/− control compared to wild-type control, P = 0.0019 Gpr43−/− compared to wild-type arthritic). Histological assessment at day 18 (right) (scale bars, 50 μm). b, OVA-induced allergic airway inflammation. BAL fluid cell counts (left), eosinophil peroxidase (EPO) activity in lung tissue (middle), and inflammation as scored by histology (right). The bottom panel shows representative haematoxylin-and-eosin-stained lung sections from wild-type and Gpr43−/− mice, and control (no OVA) mice. Scale bar, 50 μm.

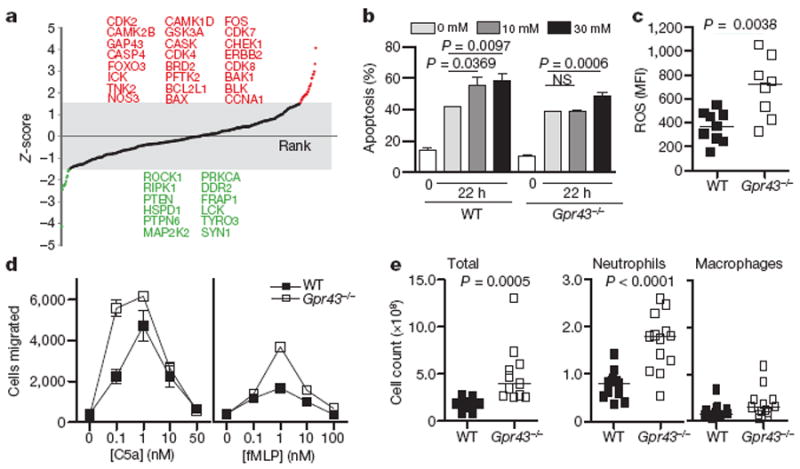

The cellular and molecular basis for GPR43–SCFA effects on inflammatory responses was studied using Kinexus protein microarrays that interrogate more than 600 proteins and phosphoproteins. Because SCFAs also inhibit histone deacetylases and thereby affect cell transcription and functions23, we made direct comparisons between wild-type and Gpr43−/− neutrophils, to identify GPR43-related signalling pathways affected by SCFAs. Protein–protein interaction networks were constructed from the set of top-ranked proteins exhibiting greatest positive or negative differential shifts (Z-scores≥1.5 and≤1.5; Fig. 4a). We applied the MCODE clustering algorithm to identify highly connected local sub-networks, which revealed interesting modules such as the apoptosis-associated BAX–BAK1–BCL2L1 cluster and the PRKCA–PTPN6–LCK cluster (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Consistent with the changes in apoptosis-related signalling molecules, acetate induced apoptosis in neutrophils in a dose-dependent and a GPR43-dependent manner (Fig. 4b), except at very high concentrations (30 mM). There were also differences between wild-type and Gpr43−/− neutrophils with respect to several other signalling pathways associated with inflammation, cell migration or apoptosis in mouse, and in human (Supplementary Figs 9 and 10). Granulocytes from Gpr43−/− mouse blood showed an increase in levels of ROS (Fig. 4c) and MPO (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, macrophages from germ-free mice also show increased production of ROS24. Gpr43−/− neutrophils also showed increased chemotaxis to the N-formyl peptide f-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP) and to the complement fragment C5a (Fig. 4d), compared to wild-type cells. Furthermore, heat-inactivated Staphylococcus aureus injected into the peritoneum of Gpr43−/− mice yielded a greater recruitment of neutrophils after 1 h, compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 4e). Acetate stimulation of human neutrophils markedly reduced surface expression of pro-inflammatory receptors such as C5aR and CXCR2 (Supplementary Fig. 11), presumably through agonist-mediated receptor heterodimerization and internalisation.

Figure 4. GPR43 signalling and immune cell functions.

a, Protein expression analysis using Kinex antibody microarrays. Z-score-transformed values reflecting positive or negative shifts in differential protein expression fold-changes after acetate treatment of neutrophils from wild-type mice compared to that from Gpr43−/− mice. Proteins highlighted in red or green indicate those with Z-scores above +1.5 or below −1.5, respectively. b, Apoptosis in wild-type and Gpr43−/− bone marrow cells, with or without acetate stimulation (apoptotic cells are annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) double positive). c, Chemotactic response to fMLP and C5a by wild-type and Gpr43−/− bone marrow granulocytes. d, Recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages to the peritoneum in wild-type and Gpr43−/− mice, injected with 1 × 106 heat-inactivated S. aureus particles. e, Reactive oxygen species production by peripheral blood granulocytes.

Commensal bacteria and vertebrate immune systems form a symbiotic relationship and have co-evolved25 such that proper immune development and function relies on colonisation of the gastrointestinal tract by commensal bacteria2,26. SCFA–GPR43 signalling is one of the molecular pathways whereby commensal bacteria regulate immune and inflammatory responses. GPR43 resembles another anti-inflammatory chemoattractant receptor, ChemR23 (ref. 27), although this receptor binds endogenous rather than bacterially produced ligands. Any agents that affect gastrointestinal microbiota, and the production of SCFAs, might be expected to influence immune and inflammatory responses. It is possible that high levels of SCFAs such as acetate may, in addition to its direct effects on the GPR43 response, affect the biosynthesis of endogenous fatty acids, such as resolvins, that modulate leukocyte functions. Levels of SCFAs in the gastrointestinal tract vary significantly depending on the amount of non-digestible fibre in the diet, and also relate to the composition of the gut microbiota12. For instance, the relative proportion of Bacteroidetes is decreased in obese people compared to lean people28. Indeed an altered composition of the gut microbiota, brought on by western diet, or by use of antibiotics, has been suggested as a reason for the increased incidence of allergies and asthma in humans29. SCFA–GPR43 interactions could represent a central mechanism to account for affects of diet, prebiotics and probiotics on immune responses, and may represent new avenues for understanding and potentially manipulating immune responses.

METHODS SUMMARY

RNA extraction, preparation, hybridization and expression analysis using U133A and B Affymetrix GeneChips (Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) accession GSE3982) were performed as previously described, using an extensive collection of immune cell data sets18. Protein expression and phosphorylation were assessed using Kinex antibody microarrays (Kinexus Bioinformatics) (http://www.kinexus.ca/services). Gpr43−/− mice on a C57Bl/6 background were obtained from Deltagen (http://wwww.deltagen.com). The K/BxN inflammatory arthritis model, the DSS and TNBS models of colitis, and the OVA allergic airway inflammation followed standard published procedures. Statistical analyses were conducted using a Student’s two-way t-test, or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Graphpad Prism software.

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank P. Silvera and S. Tangye for supply of certain Genechip data sets, L. Tsai for help with heatmaps, and D. Kobuley, J. Nicoli and M. Abt for help in the germ-free animal facilities. K.M.M. and C.R.M. are supported by the Australian NHMRC, and the CRC for Asthma and Airways. A.N. is a recipient of a Fellowship award from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. F.S. and D.Y. are Cancer Institute NSW Fellows.

Footnotes

Author Contributions C.R.M. conceived and supervised the project, and K.M.M. performed the vast majority of the in vitro and in vivo experiments (other than those detailed below) and provided intellectual input to scientific direction and interpretations. A.T.V., M.M.T. and D.A. contributed to experiments with germ-free mice. F.M., M.S.R. and F.S. identified GPR43 as a receptor with an interesting transcript expression, and A.N. and R.J.X. were responsible for all of the subsequent bioinformatic analyses. H.C.S., D.Y. and J.K. provided general support for many of the experiments.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Wen L, et al. Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development of Type 1 diabetes. Nature. 2008;455:1109–1113. doi: 10.1038/nature07336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazmanian SK, Round JL, Kasper DL. A microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestinal inflammatory disease. Nature. 2008;453:620–625. doi: 10.1038/nature07008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank DN, et al. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13780–13785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706625104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Treem WR, Ahsan N, Shoup M, Hyams JS. Fecal short-chain fatty acids in children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1994;18:159–164. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199402000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harig JM, Soergel KH, Komorowski RA, Wood CM. Treatment of diversion colitis with short-chain-fatty acid irrigation. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:23–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901053200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanauchi O, et al. Treatment of ulcerative colitis by feeding with germinated barley foodstuff: first report of a multicenter open control trial. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37(suppl 14):67–72. doi: 10.1007/BF03326417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breuer RI, et al. Rectal irrigation with short-chain fatty acids for distal ulcerative colitis. Preliminary report. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:185–187. doi: 10.1007/BF01300754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheppach W. Treatment of distal ulcerative colitis with short-chain fatty acid enemas. Aplacebo-controlled trial. German-Austrian SCFA Study Group. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:2254–2259. doi: 10.1007/BF02071409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vernia P, et al. Short-chain fatty acid topical treatment in distal ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:309–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown AJ, et al. The Orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11312–11319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Poul E, et al. Functional characterization of human receptors for short chain fatty acids and their role in polymorphonuclear cell activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25481–25489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macfarlane S, Macfarlane GT. Regulation of short-chain fatty acid production. Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62:67–72. doi: 10.1079/PNS2002207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Høverstad T, Midtvedt T. Short-chain fatty acids in germfree mice and rats. J Nutr. 1986;116:1772–1776. doi: 10.1093/jn/116.9.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tedelind S, Westberg F, Kjerrulf M, Vidal A. Anti-inflammatory properties of the short-chain fatty acids acetate and propionate: a study with relevance to inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2826–2832. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i20.2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavaglieri CR, et al. Differential effects of short-chain fatty acids on proliferation and production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines by cultured lymphocytes. Life Sci. 2003;73:1683–1690. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00490-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Segain JP, et al. Butyrate inhibits inflammatory responses through NFκB inhibition: implications for Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2000;47:397–403. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.3.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lührs H, et al. Butyrate-enhanced TNFα-induced apoptosis is associated with inhibition of NF-κB. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:1561–1568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeffrey KL, et al. Positive regulation of immune cell function and inflammatory responses by phosphatase PAC-1. Nature Immunol. 2006;7:274–283. doi: 10.1038/ni1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bader GD, Hogue CW. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee T, et al. Identification and functional characterization of allosteric agonists for the G protein-coupled receptor FFA2. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1599–1609. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.049536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki T, Yoshida S, Hara H. Physiological concentrations of short-chain fatty acids immediately suppress colonic epithelial permeability. Br J Nutr. 2008;100:297–305. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508888733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pomare EW, Branch WJ, Cummings JH. Carbohydrate fermentation in the human colon and its relation to acetate concentrations in venous blood. J Clin Invest. 1985;75:1448–1454. doi: 10.1172/JCI111847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grunstein M. Histone acetylation in chromatin structure and transcription. Nature. 1997;389:349–352. doi: 10.1038/38664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mørland B, Midtvedt T. Phagocytosis, peritoneal influx, and enzyme activities in peritoneal macrophages from germfree, conventional, and ex-germfree mice. Infect Immun. 1984;44:750–752. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.3.750-752.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ley RE, et al. Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes. Science. 2008;320:1647–1651. doi: 10.1126/science.1155725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nature Rev Immunol. 2008;8:349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444:1022–1023. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shreiner A, Huffnagle GB, Noverr MC. The “Microflora Hypothesis” of allergic disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;635:113–134. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09550-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.