Abstract

In the 50 United States and the District of Columbia law enforcement medical referrals are accepted by licensing agencies. This study assessed driving actions, medical concerns, and medical conditions in 486 police referrals to the Medical Advisory Board of the Maryland Motor Vehicle Administration during a 25-month period. Driving actions, medical concerns, and medical conditions were grouped into categories and entered into a database. These elements were analyzed relative to driver age and sex. In addition, the issuance of citations for driving violations was studied relative to age and sex. A greater percentage of drivers 60 years of age or greater (senior adults) were referred compared to the general population of licensed drivers that age, being 71.4% vs 20.6% (p <0.01). Crashing, the most common driving action, was not associated with age or sex. Among driving actions frequently mentioned relative to older drivers, only confusion of pedals was associated with senior adults drivers as compared to younger drivers (6.1% vs 0.1%, p <0.01). Of the most frequently mentioned medical concerns, confusion/disorientation was associated with being a senior adult (p <0.01), while loss of consciousness was associated with younger drivers (p <0.01). The most frequently mentioned medical conditions, diabetes and seizure, were associated with being under 60 years of age. All mentions of dementia were in senior adult drivers. Compared with younger drivers, drivers 60 years of age or older, were less often summoned for driving violations, being 33.0% vs 53.5% (p <0.01), respectively. The threshold for the issuance of fewer citations was lower for men (40 to 59 years of age) compared to women (60 years of age or greater). Studies are needed to correlate specific traffic violations and/or crashes to specific medical conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Over four decades have passed since Julian Waller’s (1965) seminal paper on chronic illness and medical fitness to drive was published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Excluding alcoholism, he noted that in 1963 that “at least” 15 percent of California drivers had one or more of the following medical conditions: “heart disease,” diabetes, epilepsy, “history of admission to a state mental hospital in past ten years,” “orthopedic handicaps,” impaired vision and/or impaired hearing. Waller estimated that five to ten percent of California crashes were associated with medical conditions.

In 2003, medical fitness to drive was the focus of two important initiatives. In March of that year the National Transportation Safety Board held a two-day public hearing on Medical Oversight of Noncommercial Drivers [NTSB, 2004]. This discussion was introduced by a presentation of six crashes involving drivers who had sudden medical emergencies. Five had suffered seizures and one a diabetic “black out.” In addition to the 2.5 million people with epilepsy and 18.2 million with diabetes, it was estimated that the numbers of Americans with the following other conditions “offer some perspective on the medical oversight issues that State licensing agencies face”: sleep disorders (50 to 70 million), cardiovascular disease (23.5 million); Alzheimer’s Disease (4.5 million), arthritis (40 million), eye diseases (5.5 million-cataracts, 2 million-glaucoma, 1.2 million-later stage macular degeneration), and 14 million with alcoholism [NTSB; 2004, pages vii and viii].

NTSB [2004] testimony indicated that the percentage of drivers with medical concerns who were referred to licensing agencies by the police varied widely by jurisdiction, ranging from 35 to 90 percent. Between the years 2000 and 2002, police referred 17,642 drivers in Florida and 43,340 drivers in North Carolina who were involved in crashes to the medical review units of the licensing agencies in those states.

A recent report of Meuser and colleagues (2009), documents referrals for medical fitness to drive among individuals 50 years of age or greater, two years after the introduction of a Missouri law allowing for voluntary reporting of drivers by physicians, police officers, and others. The statute provides for confidentiality of the reporter and for civil immunity protection if there is a breach of confidentiality. In the five calendar years of 2001 through 2005, a total of 5362 drivers were referred, 93% of whom were 50 years of age or older. For those in that age group for whom complete data were available, 30% of reports were from police, 27% by licensing agency staff, 20% by physicians, 16% by family members and 7% by others.

In June 2003, three months after the NTSB hearing on medical review, Lococo [2003] published her comprehensive survey, Summary of Medical Advisory Board Practices in the United States involving the 50 states and the District of Columbia. She documented that in all jurisdictions agencies accepted reports concerning medical fitness to drive from the police, and that as result of such reports, drivers could be subject to a medical review. Lococo also reported that in 35 of the 51 jurisdictions, licensing agencies had a functioning medical advisory board.

A review of Lococo’s (2003) report indicates that the oldest licensing agency Medical Advisory Board in the United States is the one established in Maryland in 1947. By law, the Administrator of the Maryland Motor Vehicle Administration (MVA) may appoint a Medical Advisory Board (MAB). Further, Administration may refer drivers to the MAB for “an advisory opinion, in the case of any licensee or applicant for a license, if the Administrator has good cause to believe that the driving of the vehicle by him would be contrary to public safety and welfare because of an existing or suspected mental or physical ability [Maryland Transportation Article §16–118, 2008].”

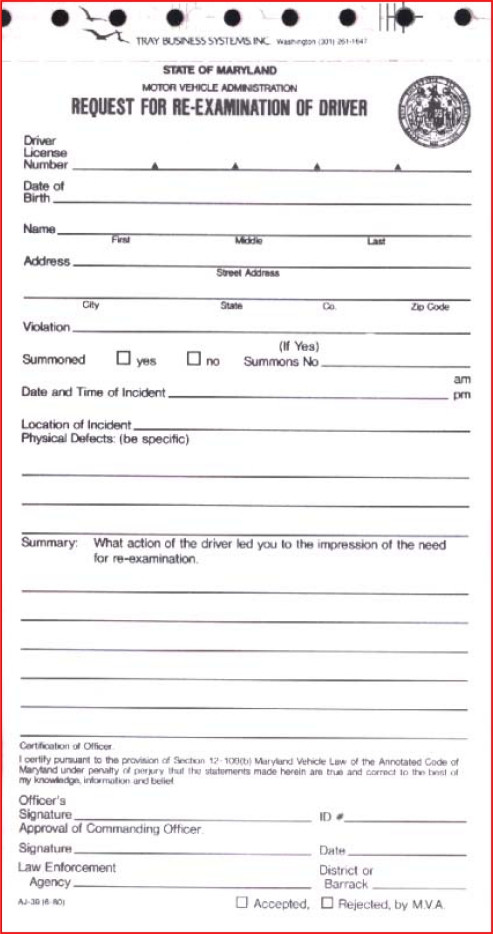

Over the past 60 plus years, the Maryland MVA and its Medical Advisory Board has developed a comprehensive system of referral and evaluation for medical fitness to drive [Soderstrom & Joyce, 2008]. In addition to the self-report of medical conditions by clients, and referrals from clinicians, the Maryland MVA accepts reports from police officers in the form of a Request for Re-examination (RRE) [Figure]. The vast majority of these reports voice concerns about medical fitness to drive stemming from encounters with drivers as the result of a traffic stop – including those involving a crash. In addition to fields for driver information; date, time and location of the traffic incident; violation/summons information, the RRE has space for the officer to provide verbiage concerning two elements. They are: “What action of the driver led you to the impression of the need for re-examination?” and “Physical Defects: (be specific).”

Request for Re-examination reports are submitted to the MVA’s Driver Wellness and Safety Division and reviewed by Administrative Nurse Case Reviewers or their Supervisor. If the RRE raises immediate concerns about fitness to drive, that report is referred to the Medical Advisory Board. Many of these referrals involve reports of significantly altered states of consciousness. These altered states may be the manifestation of an acute medical episode such as seizure, hypoglycemia in a person with insulin-dependent diabetes, or disorientation due to suspected dementia, medication effects, or alcohol/drug abuse. In addition, a report of severe physical limitations such as poor vision, extreme weakness and/or slow movement/reflexes, raise concerns that result in MAB review. As the result of such referrals, the MAB recommends suspension of the driving privilege in about two-thirds of cases until an evaluation for medical fitness to drive is conducted. A driver is afforded the option of an administrative hearing within seven days to appeal an emergency suspension. In the vast majority of cases where drivers choose that option, the suspensions are upheld by the administrative law judge.

STUDY PURPOSE AND HYPOTHESES

The purpose of this study was to review the reasons why police refer drivers for medical review. In addition, we wanted to gain an understanding of the demographic profile of referred drivers relative to age and sex. There were two study hypotheses: 1) the majority of referred drivers would be 60 years of age or older, and 2) when a driving violation was associated with the traffic encounter, compared with younger drivers, drivers 60 years of age or older would be less likely than younger drivers to have been issued a summons for that violation.

HUMAN SUBJECTS

This study was found to meet the criteria to be exempt from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) process by the University of Maryland IRB (Baltimore, MD).

METHODS

Information from Request for Re-examination report submitted for review by the Maryland MVA’s Medical Advisory Board for the 25-month period March 2005 through April 2007 was entered into a database. Data elements from the RREs included driver demographic information (date of birth, driver’s license number, address), traffic incident information (date, time and location of the event), violation codes, issuance of a summons (yes or no), and summons number. In addition, the officer’s narrative summary of the action(s) that led to the RRE and narrative comments about medical concerns (including “physical defects”), medical conditions mentioned at the traffic scene. Driving actions, medical concerns, and medical mentions were grouped into categories. Creation of data elements and categories for each of these data sets are discussed below.

Age groups

For the purposes of this study, drivers were divided into four age groups. They consisted of drivers 17 to 39 years of age, 40 to 59 years of age, 60 to 79 years of age, and 80 years of age or greater. The Maryland Department of Aging designates a person who has reached the age of 60 years as a “senior citizen.”

Driving Actions

Driving actions were derived from the officer’s narrative summary and violation code(s) recorded in the request. They were grouped into 11 categories as follows (parentheses provide examples of actions included in the category): 1) crashed, 2) drove too fast, 3) drove too slow (drove well below the posted speed and/or impeded the flow of traffic, 4) drove erratically (weaved, drove on the shoulder, tailgated, etc.), 5) left the scene of the incident, 6) ignored lights and siren, 7) ran a control (stop sign, traffic signal, controlled area such as police and rescue scenes), 8) drove the wrong way, 9) struck a pedestrian, 10) assault driving (drove with the apparent intent to strike a person, a vehicle, or an object, 11) confused pedals – this action was usually derived as the result of communication between the driver and the officer.

Medical Concerns

Medical concerns were derived from officer narrative information in the request for re-examination in which the officer noted functional medical concerns that may have contributed to the occurrence of the traffic event. Examples: the officer noted the driver appeared to be confused and/or disoriented, it was noted that the driver appeared to be shaky or weak or had trouble walking, the driver was unconscious, etc. Medical concerns were grouped into 13 categories as follows (parentheses provide examples of concerns included in the category): 1) loss of consciousness (this included seizure, “blackouts”, etc.), 2) problem with vision, 3) difficulty hearing, 4) slow reactions (including mentions of slow movements, being weak and shaky, etc.), 5) confusion (including mentions of disorientation, being lost, did not understand what happened or why, etc.), 6) difficulty with gait (including difficulty walking, problems with balance, use of cane or walker, etc.), 7) delusions (as the result of the driver reporting situational, visual, or auditory information that was not consistent with reality), 8) panic attacks (the driver mentioned a high degree of anxiety that precluded the ability to drive safely), 9) alcohol impairment, 10) drug impairment (including mention/evidence of possible use of illegal substances), 11) medication impaired (the driver mentioned untoward effects of medications or taking medication(s), or medications with psychoactive properties were mentioned or found in possession of the driver), 12) elderly age was mentioned, and 13) other concerns not included in 1 through 12.

Medical Conditions

Medical conditions were derived from officer narrative information in the Request for Reexamination about medical conditions related by the driver, an occupant with the driver, or in some cases, pre-hospital medical personnel called to the scene of the traffic event. Examples: there is mention of a particular medical diagnosis, such as insulin requiring diabetes, epilepsy, dementia, there is mention of being ill, or being in recovery from an illness or medical procedure. Medical conditions were grouped into 14 categories as follows (parentheses provide examples included in the category): 1) diabetes, 2) seizure (including epilepsy, and seizures resulting from medications and alcohol), 3) cardiac problems (including mentions of cardiac events such as myocardial infarction or cardiac syncope, taking of cardiac medications, cardiac procedures such as cardiac bypass surgery, coronary artery stenting or angioplasty, placement of a pacemaker), 4) psychiatric conditions (bipolar disorder, schizo-affective disorders, panic attacks, attention deficit disorder), 5) vision problems (cataract, macular degeneration, glaucoma, partial blindness), 6) multiple sclerosis, 7) Parkinson’s disease, 8) sleep disorders (obstructive sleep apnea, narcolepsy, etc.), 9) alcohol use problem, 10) drug use problem, 11) dementia, 12) being ill, 13) central nervous system (CNS) (stroke, “mini-strokes”, brain tumor), 14) other CNS problems (paraplegia), and 15) other medical problems. These conditions include reportable medical conditions, e.g., conditions that drivers in Maryland are expected to report to the MVA at the time of license application or renewal.

Violations

Determining if there was a driving violation associated with the traffic event was ascertained by the presence in the Request for Re-examination of any of the following: 1) the officer’s narrative described the driver as performing an illegal action (examples: drove through a control device or signal, drove too slow for conditions, speeding, etc), 2) a traffic code violation number was cited, 3) “yes” was checked for summons was issued, and 4) a summons number was provided. Note: While the request has the appearance of a summons [Figure], no charge or points against the driver results from a RRE referral to the MVA.

Analyses

Chi-square analysis was used with a p value of <0.05 being considered significant.

RESULTS

Demographics

A total of 486 Request for Re-examination reports submitted by law enforcement to the Maryland MVA were referred for review to the Medical Advisory Board. Sex and age information is presented in Table 1. As noted 57.8% were men and 72.4% were 60 years of age or greater. Ages ranged from 17 years to 100 years of age. Six per cent of the drivers were ninety years of age or greater, of whom 10 (0.9%) were 95 years of age or older.

Table 1.

Demographics of Drivers Referred for Re-examination Compared with all Noncommercial Licensed Drivers in Maryland for 2007

| RRE Referred [n=486] |

All Noncommercial Licensed MD Driversa [n=3,440,110] |

P |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Percent | No. | Percent | ||

| Sex: | |||||

| Men | 281 | 57.8 | 1,534,774 44.6 | ||

| Women | 205 | 42.2 | 1,905,336 55.4 | <.01b | |

| Age Groups: | |||||

| 17–39 years | 53 | 10.9 | 1,069,182 | 31.1 | |

| 40–59 years | 86 | 17.7 | 1,661,779 | 48.3 | |

| 60–79 years | 166 | 34.2 | 599,382 | 17.4 | |

| 80 years and older | 181 |

37.2 |

109,767 |

3.2 |

<.01c |

| 486 | 100.0 | 3,440,110 | 100.0 | ||

Data Courtesy: Ms. Jennifer Hine, Maryland MVA, Driver Services; Glen Burnie, MD; April 6, 2009.

Comparison of percent of women in the medically referred group with percent of all women with noncommercial driver licenses.

Comparison of percent of drivers 60 years of age or older in the medically referred group with all noncommercial licensed drivers 60 years of age or older.

Driving Actions

Overall, 762 driving actions were noted for the 486 drivers referred to the MAB. These actions are summarized in Table 2. By far the most common action was crashing, with almost 60% of drivers being involved in a collision. The percentage of drivers crashing in the various age categories ranged from 53.6% among those 60 to 79 years of age to 67.4% among those 40 to 59 years of age. There was no significant difference in the percent of referred drivers who crashed relative to sex, with 61.5% of women and 57.3% of men, respectively being involved in collisions. After crashing, the most common actions noted by the police were driving erratically (35.8%), running a control device (13.5%) and leaving the scene of the traffic stop (11.9%).

Table 2.

Driving Actions of Drivers Referred for Re-examination

| Action | No. | Percent of Drivers with Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Crashed | 287 | 59.1 |

| 2. Fast driving | 26 | 5.3 |

| 3. Slow driving | 22 | 4.5 |

| 4. Erratic Driving | 174 | 35.8 |

| 5. Left the scene | 58 | 11.9 |

| 6. Ignored lights & sirens | 26 | 5.3 |

| 7. Ran a control | 66 | 13.5 |

| 8. Drove the wrong way | 37 | 7.6 |

| 9. Struck a pedestrian | 20 | 4.1 |

| 10. Drove to assault | 6 | 1.2 |

| 11. Confused pedals | 22 | 4.5 |

| 12. Other | 18 |

3.7 |

| 762 |

Particular driving actions, which are often cited as being associated with a decrease in cognitive function as a result of the aging process in senior drivers, were assessed. Overall, we found that compared with younger drivers, a greater percentage of these actions were noted among drivers 60 years of age or older. They were as follows: confused pedals, 6.1% vs 0.1% (p<0.01); ignored lights and sirens, 6.3% vs 2.8% (NS); drove too slow for conditions, 5.2% vs 2.9% (NS); ran a control, 15.0% vs 10.1% (NS); and drove erratically 37.8% vs 30.9% (NS). As noted, only confusion of pedals was an action that was significantly associated with senior adult drivers.

Police Concerns

Police mentioned 580 medical concerns which are presented in Table 3. One notes that altered states of consciousness either as confusion/disorientation (n=196, 40.3%) or as loss of consciousness (n=85, 17.5%) were the most common concerns, followed by possible vision problems (n=70, 14.4%). Confusion/disorientation concerns were over four times more frequent among drivers 60 years of age or greater compared with younger drivers; being 48.1% versus 11.1% (p<0.01). In contrast, loss of consciousness (LOC) concerns were over four times higher among drivers less than 60 years of age compared with older drivers; being 38.1% versus 9.2% (p<0.01). It is important to note that while 59.1% of all referred drivers were involved in a crash, almost 90% of all drivers with a LOC were involved in collisions. There was no significant difference in the percent of drivers under the age of 60 (5.8%) and those 60 years of age or greater (10.1%) with mentions of slow reaction times.

Table 3.

Medical Concerns Mentioned by Police of Drivers Referred for Re-examination

| Medical Concern | No. | Percent of Drivers with Concern Mentioned |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Loss of consciousness | 85 | 17.5 |

| 2. Vision problem | 70 | 14.4 |

| 3. Hearing problem | 20 | 4.1 |

| 4. Slow reaction/weak | 43 | 8.8 |

| 5. Confused/disoriented | 196 | 40.3 |

| 6. Walking/gait problem | 37 | 7.6 |

| 7. Delusional | 10 | 2.1 |

| 8. Panic/anxiety | 5 | 1.0 |

| 9. Alcohol impaired | 7 | 1.4 |

| 10. Drug impaired | 6 | 1.2 |

| 11. Medication impaired | 31 | 6.4 |

| 12. Elderly | 34 | 6.9 |

| 13. Other. | 36 |

7.4 |

| 580 |

Medical Conditions

Medical conditions mentioned by the driver, a family member or a friend, or a pre-hospital provider at the traffic scene are summarized in Table 4. As noted, the most common specific medical conditions were seizure/epilepsy (6.0%) and diabetes (5.8%). The percentage of mentions of these conditions were over two and seven greater among the drivers under the age of 60, compared with the older drivers; being 9.4% versus 4.3% for diabetes (p<0.03) and 15.8% versus 2.0% for seizure/epilepsy (p<0.01), respectively. While the vast majority of mentions for psychiatric conditions were among drivers under 60 years of age compared with older drivers (n=15, 10.2% vs n=3, 0.9%), all 15 mentions of dementia involved senior adult drivers.

Table 4.

Medical Conditions of Drivers Mentioned in Request for Re-examination Reports

| Medical Condition | No. | Percent of Drivers with Condition Mentioned |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Diabetes | 28 | 5.8 |

| 2. Seizure/epilepsy | 29 | 6.0 |

| 3. Cardiac problem | 7 | 1.4 |

| 4. Psychiatric problem | 18 | 3.7 |

| 5. Vision problem | 13 | 2.7 |

| 6. Parkinson’s disease | 3 | 0.6 |

| 7. Sleep disorder sleep | 1 | 0.2 |

| 8. Alcohol use problem | 3 | 0.6 |

| 9. Drug use problem | 1 | 0.2 |

| 10. Dementia | 15 | 3.1 |

| 11. CNS problema | 11 | 2.3 |

| 12. CNS, other problemb | 7 | 1.4 |

| 13. Currently ill | 41 | 8.4 |

| 14. Other | 28 |

5.8 |

| 205 |

CNS = central nervous system: stroke, “mini-stroke,” brain tumor

CNS, other problem: paraplegia, etc.

Note: The study database had a field for multiple sclerosis, a “reportable condition” in Maryland. There were no mentions of multiple sclerosis in the Request for Re-examinations.

Violations

Over 80% of the 486 drivers committed one or more driving violations. The percent of drivers with a least one violation was similar for those less than 60 years of age and for senior drivers, being 80.6% and 82.1% respectively. Overall, 38.5% of the drivers committing violations were issued citations. Table 5 presents violations and citation data for each of the four age groups. Of the drivers less than 60 years of age who committed violations, 53.5% were issued citations. In contrast, only 33.0% of drivers 60 years of age or older were issued citations (p<0.01).

Table 5.

Driving Violations and Traffic Citations Issued by Age Among Driver Referred to the Medical Advisory Board

| Age Group | Violation Committed | Citation Issued (Percent) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17–39 years | 42 | 25 (60.0) | |

| 40–59 years | 72 | 36 (50.0) | |

| 60–79 years | 134 | 45 (33.4) | |

| 80 years or older | 151 |

49 (32.4) |

<.01a |

| 155 (38.8) |

Comparison of citations issued to drivers less than 60 years of age with older drivers.

Relative to sex and issuance of citations for driving violations, women 60 years of age or older were less likely to be issued citations compared with younger drivers; being, 27.9% vs 67.4% (p<0.01), respectively. In contrast, among male drivers the lower rate of citation issuance occurred at 40 years of age or greater, being 34.1% for those 40 to 59 years of age, 34.3% for those 60 to 79 years of age, and 39.5% for men 80 years of age or greater (p<0.01).

While a number of reasons may explain the significantly lower rate of issuance of citations for violations among senior adult drivers (see discussion), the one that most readily comes to mind is that officers did not want to cite a person for whom they felt compassion. To explore this possibility, citation rates were assessed among younger and older drivers who had any indication of possible frailty (physical or mental). Citation rates were analyzed for younger and older drivers who had any mention of the following police concerns: confused/disoriented, slow reaction time/weak, or older age. There were a total of 186 drivers with violations without mentions of the “frailty” concerns and 213 for whom one or more of these concerns were mentioned. Overall, the significant difference in the issuance of citations for drivers less than 60 years of age compared to older drivers with and without “frailty” concerns remained. For those without “frailty” concerns, the citation rate was 53.6% among drivers younger than 60 years vs 31.7% among older drivers (p<0.01). Similarly, among drivers in which “frailty” concerns were mentioned, 53.1% of drivers less than 60 years of age were summoned compared with 33.7% of older drivers (p<0.04).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the reasons that prompt police officers to refer drivers to a Medical Advisory Board relative to specific driving actions and specific medical concerns and conditions. The reasons for referral focused on driving actions, concerns about physical/cognitive function observed by the officer, and medical conditions/diagnoses of concern mentioned at the time of the traffic encounters.

Our first significant finding of note is that, compared with the overall population of licensed noncommercial drivers in Maryland, drivers 60 years of age and greater were over represented in those referred to the Medical Advisory Board. Considering that the aging process is associated with the emergence of, or the worsening of physical and mental problems that can affect the ability to drive safely, this finding is not surprising [NTSB, 2004].

During the period of study there was a similar majority of women senior adult drivers in Maryland (56.2% of drivers over 60 of age) and the 2007 U.S. population (57.2% of those 65 years of age or greater) [U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2009]. The reason that men were over represented among the referred drivers compared to the general noncommercial licensed population may be a matter of exposure. According to the 2001 National Household Travel Survey [Hu & Reuscher, 2004], compared to men, women took 20% fewer vehicle trips per day, and they traveled 29% fewer miles per day.

It appears that the reasons that prompted law enforcement to refer drivers to the Medical Advisory Board were based on driving actions observed and observed medical concerns. Overall for the 486 drivers referred, 762 driving actions and 580 observed medical concerns were mentioned. There were a total of 281 mentions of confusion/disorientation (n=196) and loss of consciousness (n=85), and another 80 mentions involving either slow action/reactions (n=43) or problems with gait (n=37). In contrast, there were only 205 medical conditions/diagnoses mentioned in the narrative summaries.

While almost 60% of the 486 drivers were referred because of concerns about medical fitness to drive, this study could not determine whether medical conditions were related to crash causation. Indeed, while there is an expanding body of literature on medical conditions and driving [Dischinger et al, 2000; Sheth et al, 2004; Dobbs, 2005], we are not aware of any prospective controlled studies linking individual crashes with specific medical conditions. This includes a review of the considerable efforts of Charlton and colleagues [2004] and Dobbs [2005]. This dearth of information was noted in the NTSB medical oversight hearing which reached the following conclusion, “A system is needed for the collection of accident data on a national basis to comprehensively evaluate the extent to which medical conditions play a role in accident causation [NTSB, 2004, page 54].”

As noted, while in this study and others it is not possible to conclude that a specific medical condition was the cause of a crash, a loss of consciousness (LOC) is highly correlated with crash causation. The two most common causes of LOC associated with crashes is seizure, most commonly occurring in individuals with a diagnosis of epilepsy [Sheth et al, 2004], and severe hypoglycemia in individuals with diabetes who require insulin to control their blood glucose levels [Cox et al, 2003; Songer, 2006]. Of note, while 59.1% of the 486 drivers in this study who were involved in collisions, almost 90% of all drivers who had a LOC crashed. This finding is consistent with Dischinger and colleagues’ [2000] study of associated medical conditions among injured Maryland drivers who required hospitalization. In that study in which police reports attributed crash culpability, by far the condition with highest odds ratio that was associated with crash culpability was syncope (the same as LOC), being 4.06.

A report by McGwin and Brown [1999] provide some evidence that illness is linked to crash causation, particularly among older drivers. In their study of over 236,00 drivers involved in crashes in Alabama, they found that 8.4% of those 55 years of age or greater were noted to be “ill” on the police report compared to 3.3% of drivers 35–54 years of age and 1.4% of drivers less than 35 years of age (p<0.001). In this study the police indication of “ill” did not designate any specific medical conditions.

A key finding of this study is that police summoned senior adult drivers who committed traffic violations significantly less than younger drivers, i.e., those less than 60 years of age. As part of our analyses, we explored as a possible explanation for this finding that observable characteristics associated with frailty could have played a role. Results did not support empathy for frailty as an explanation. Another plausible explanation is noted in the recently published National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s training manual for police officer interacting with senior adult drivers [NHTSA 2006]. It is noted that it may be difficult for an officer to ticket someone “who may remind them of their parents or grandparents.” This empathy may result in referral for a possible medical concern to the licensing agency, without issuance of a summons for a traffic violation.

It is not uncommon that issuance of a summons for a violation that is associated with referral to the Medical Advisory Board may be the first blemish on a senior driver’s record, or their first involvement in a crash [McGwin & Brown, 1999; McGwin et al, 2000; Ball et al, 2006]. When a summons is not issued, the driver may indicate to family members and their doctor that the traffic stop prompting medical referral was of little concern noting, “I wasn’t even given a ticket.”

As noted earlier, two independent initiatives in 2003 focused on medical fitness to drive as an important matter deserving national attention. As a result of the first initiative, the National Transportation Safety Board report (2004) on Medical Oversight of the Non-Commercial Driver noted that while police routinely encounter “unsafe driving behaviors and incapacitated drivers,” they have little training in recognizing medical problems during traffic stops, including the investigation of crashes. Noting that police often receive training to recognize drivers impaired as the result of alcohol and other drugs, training in the recognition of other medical impairments is rare. Recognizing this absence of training, the NTSB recommended that a program be developed “to help police identify common medical conditions that can impair a driver’s ability to operate a motor vehicle and then promote this training to all new and veteran officers [page 45].” A response to that recommendation has been the Older Driver Law Enforcement Course [NHTSA, 2006].

A possible limitation of the current study is bias in the drivers referred to the MAB by law enforcement. While the Request for Re-examination report form has been universally available for use by Maryland police officers for many years, until recently they were provided with little training regarding assessing medical concerns and submission of Request for Reexamination reports. It is not known if there are individual officer biases in the referral process. Relative to biases, it is not known if officer referrals varied by severity of crash, including crashes which involved personal injury. Overall, reports indicated that there were personal injuries sustained in 24 (8.4%) of the 287 crashes. There were six personal injury crashes in each age group. It is possible that for a crash involving a medical condition and transport to hospital, that an officer assumed the treating physician would make a referral to the MAB. Although police officers may not be aware that physicians are not required to report medically impaired drivers in Maryland, state law allows for reporting with immunity from civil and criminal action provided confidentiality is not violated and the referral is done in good faith.

It is important to note that the amount of information provided by officers on the RRE reports varied from sparse comments to detailed descriptions. It was not unusual for an officer to use two report forms to provide pertinent information for one traffic incident. In some cases officers included the crash investigation reports.

A specific limitation of this study is that we did not assess prior crashes and violations among those who were referred to the MAB. In their recent report, Meuser and colleagues [2009] found that among the drivers 55 years of age who were referred to the licensing agency because of medical concerns by police, physicians and others, 33% of the referred drivers has a recent prior crash compared to 12% of controls.

There is another limitation of this study worth noting. Of no surprise we found that loss of consciousness was associated with crashing about 90% of time. However, because of the relatively small number of referred drivers (n=486) compared with long lists of specific medical concerns and conditions in this study, we could not assess which were associated with specific driving actions and crashing. As noted above, McGwin and Brown [1999] in their study of a very large cohort of drivers who crashed in Alabama found that being “ill” was significantly associated with the oldest drivers, i.e., those 55 years of age or older. While “ill” was not linked to specific conditions, they found that compared with younger drivers, older drivers were more often involved in intersection crashes, and those involving running of controls, not yielding the right of way, changing lanes and making turns.

The Lococo [2003] initiative reviewing medical advisory practices led to review of appropriate strategies for medical advisory boards and license agency review [Lococo & Staplin, 2005]. As part of that effort, “key licensing officials and medical staff” in 45 jurisdictions were asked to complete a Relative Value Assessment exercise concerning practices which deserve priority. Of 16 components, “use of external, non-medical triggers for review,” was ranked seventh. Of the four external triggers (law enforcement/courts, family, social services, general public), law enforcement/courts was rated the highest.

CONCLUSIONS

Law enforcement serves as a valuable resource in the referral of drivers to licensing agencies with significant medical concerns that affect their ability to drive safely. This is particularly true of drivers who suffer losses of consciousness. Among referred drivers who commit driving violations, there are low citations rates among senior adult drivers. This may be the result of empathy/respect for senior citizens. Studies are needed to correlate specific traffic violations and/or crashes to specific medical conditions.

Figure 1.

State of Maryland police officer Request for Re-examination of Driver report form for referral to the Motor Vehicle Administration.

Note: The officer is provided space to present narrative information for 1) “Physical Defects: (be specific),” and “Summary: What action of the driver led you to the impression of the need for re-examination?”

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Albert L. Liebno Jr, Lieutenant retired Maryland State Police, for our education and insights into Maryland police training for medical fitness to drive. Mr. Liebno is the Skills Training Administrator for the Maryland Police & Correctional Training Commissions in charge of training police officers in skill/performance related training, including assessment and referral of drivers with medical concerns to the MVA.

REFERENCES

- Ball KK, Roenker DL, Wadley VG, et al. Can high-risk older drivers be identified through performance-based measures in a department of motor vehicles setting? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton J, Koppel S, O’Hare, et al. Influence of chronic illness on crash involvement of motor vehicle driversMonash University Accident Research Center, Report No. 213; Melbourne, Australia: Monash University; April2004 [Google Scholar]

- Cox DJ, Penberthy JK, Zrebiec J, et al. Diabetes and driving mishaps, frequency and correlations from a multinational study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2329–2334. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dischinger PC, Ho SM, Kufera J. Medical conditions and car crashes. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med. 2000;44:335–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs BM.Medical conditions and driving: a review of the scientific literature (1960–2000). Technical report for the National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration and the Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine Project. Report DOT HS 809 690; Washington (DC); 2005

- Hu PS, Reuscher TR. Summary of Travel Trends, 2001 National Household Travel Survey. Federal Highway Administration, U. S. Department of Transportation; Washington, DC: Dec, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lococo KH. Summary of Medical Advisory Board Practices. Transanalytics; Kulpsville, PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lococo KH, Staplin L.Strategies for Medical Advisory Boards and Licensing Review National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; Washington, DC: DOT HS 809 874; July2005 [Google Scholar]

- McGwin G, Jr, Brown DB. Characteristics of traffic crashes among young, middle-aged, and older drivers. Accid Anal Prev. 1999;31:181–198. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(98)00061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGwin G, Jr, Sims RV, Pulley L, et al. Relations among chronic medical conditions, medications, and automobile crashes in the elderly: a population-based case-control study. Am J Epidemiology. 2000;152:424–431. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.5.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuser TM, Carr DB, Ulfarsson GF. Motor-vehicle crash history and licensing outcomes for older drivers reported as medically impaired in Missouri. Accid Anal Prev. 2009;41:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) Older Driver Law Enforcement Course, Participant Manual NHTSA; Washington, DC: HS 00577 R7/06, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- National Transportation Safety Board: Highway Special Investigation Report: Medical Oversight of Noncommercial Drivers. NTSB; Washington, DC: NTSB/SIR-04/01, PB2004-917002, November92004

- Sheth SG, Krauss G, Krumholz A, Li G. Mortality in epilepsy: driving fatalities vs other causes of death in patients with epilepsy. Neurology. 2004;63:1002–1007. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000138590.00074.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom CA, Joyce JJ. Medical review of fitness to drive in older drivers: the Maryland experience. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2008;9:341–348. doi: 10.1080/15389580801895301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songer TJ, Dorsey RR. High-risk characteristics for motor vehicle crashes in persons with diabetes by age. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med. 2006;50:335–351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transportation Article , §16–118, The Maryland Vehicle Law Annotated — 2008 Edition Maryland Vehicle Administration; Glen Burnie, MD [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census The 2009 Statistical Abstract, The National Data Book, Table 33. Available at http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/population.html Last accessed April 19, 2009.

- Waller JA. Chronic medical conditions and traffic safety: a review of the California experience. N Eng J Med. 1965;273:1413–1420. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196512232732605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]