Abstract

This paper models the effects on crash fatalities and costs of 20 years of legislative actions resulting from Federal and state advocacy efforts. We catalogued road safety laws passed between 1990 and 2009 and motorcycle helmet law repeals that advocacy efforts narrowly defeated. We used NHTSA’s estimates of lives saved by airbags and published estimates of the percentage reduction in related crash fatalities associated with each type of law. State by state and year by year, from the actual fatality count for the year, we modeled how many fatalities each state's laws averted. We assumed, somewhat shakily, that the percentage reduction in nonfatal injury costs would mirror the fatality reduction. We used crash cost estimates for 10 years between 1990 and 2008 to estimate total crash costs from 1990–2009. The costs were built from NHTSA’s estimates of cost per crash. The state laws passed included 113 occupant protection laws, 131 impaired driving laws, and 76 teen driving laws, plus a Federal airbag mandate. These laws saved an estimated 120,000 lives. The life-saving benefits accelerated as the number of laws in force grew. By 2009, they resulted in 25% fewer crash fatalities. The largest life-saving benefits sprang from airbag, belt use, and impaired driving laws. Laws that affect narrow subpopulations had more modest impacts. The laws reduced insurance costs by more than $210 billion and saved government an estimated $42 billion. Including the value of lost quality of life, estimated savings exceeded $1.3 trillion. Legislative advocacy is truly a spark plug in the safety engine.

INTRODUCTION

The venerable Haddon matrix (1970) identifies the social environment as one of the four ways we can influence the chance for and outcomes of injury. The social environment revolves around community norms. Those norms determine the range of safety laws, regulations, policies, and enforcement that are politically feasible.

Advocacy is the trumpet that leads the public policy charge. It regularly prompts changes in norms, laws, and implementing policies and enforcement. Formally, advocacy is defined as giving public support to an idea, a course of action or a belief (Oxford University Press, 2011). U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglass (1980) wrote that “freedom of expression as used in the First Amendment” protects all shades of advocacy from lukewarm endorsement to partisan promotion,” not merely “teaching in the abstract.” It “can come so close to the line where action commences that the two become brigaded.”

Formation of Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) in 1980 and Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety (Advocates) late in 1989 ushered in an era of focused legislative advocacy aimed at changing societal norms and passing Federal and State road safety legislation. Advocates’ power base and focus are broader than MADD’s, a national alliance of insurance companies and consumer, health, and safety organizations who partner with victims to make road users safer.

This paper evaluates the success of 20 years of highway safety legislation that advocacy helped to pass or protect from repeal. It counts the State laws passed from 1990 to 2009. Then it estimates the lives and money saved by those laws and one key Federal law that took effect in 1995.

METHODS

The first step in our evaluation was to catalog State highway safety laws passed between 1990 and 2009. Much of that catalog was available on the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration web sites (http://www.iihs.org/laws/default.aspx; http://www.nhtsa.gov/Laws-Regs) or in data sets colleagues at our institution had compiled to evaluate highway safety laws (Fell, Fisher, Voas, et al., 2008). We also relied on an unpublished history that Advocates compiled listing all the laws they helped to pass (http://www.saferoads.org/2011-roadmap-state-highway-safety-laws). That history also identified motorcycle helmet law repeals that major advocacy efforts narrowly defeated.

Effectiveness of the Laws

We used NHTSA’s (2009, 2010) estimates of lives saved by airbags, a safety device mandated by a 1991 Federal law. We relied on published evaluations of average reductions in fatalities to analyze the State laws. The effectiveness sources and our choices for laws governing driver licensing and qualifications follow.

(1) Administrative license revocation from estimates of a 9% reduction in nighttime fatal crashes in Illinois, Mississippi and Nevada (Lacey, Jones and Stewart, 1991); a 5%–9% reduction in nighttime crashes in New Mexico (Ross, 1987); a 6% reduction in fatal single-vehicle nighttime crashes in eight States (Zador, Lund, Field, et al., 1988); and a 6% reduction in the rate of fatal crash alcohol involvement (Klein, 1989). Following Miller, Lestina and Spicer (1998), the analysis uses a 6.5% reduction in alcohol-involved fatalities.

(2) Zero tolerance laws from multi-State analyses estimating reductions of 17% (Hingson, Heeren and Winter, 1994) to 24% (Voas, Tippetts and Fell, 2003) in alcohol-related fatal crashes involving youth. The analysis uses a 20% reduction, which equates to a 4% reduction in all DUI fatalities because these laws only affect drivers under age 21.

(3) .08 laws from a meta-analysis that estimated a 14.8% reduction across 18 states and the District of Columbia (Tippetts, Voas, Fell, et al., 2005). An earlier systematic review of studies on effectiveness concluded the average reduction in alcohol-related fatalities is 7% (Shults, Elder, Sleet, et al., 2001) with considerable variability between States.

(4) Graduated driver licensing (GDL) for ages 16–17 from an evaluation of the impact on involvement of these drivers in fatal crashes nationally (11%–21%, Baker, Chen and Li, 2006). The analysis uses a conservative 11% reduction, in part because some states did not adopt all components of the model GDL law. Shults (2010) finds the average fatal crash with a driver age 16–17 involved 1.14 fatalities.

(5) Required ignition interlock for impaired drivers from data in Voas, Marques, Tippetts et al. (1999). An interlock is estimated to have a specific deterrence effect on the sanctioned driver of 44% relative to hard suspension, or approximately 72%–78% relative to no sanction. Analysis of 1999–2000 Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) crash fatality census data shows that 9.35% of alcohol-related fatal crashes involved recidivists. These estimates suggest that if widely implemented, an interlock program would reduce alcohol-involved fatalities by 6%–10% while on the car. The analysis uses a conservative 7% reduction (9.35% * 75%).

The effectiveness estimates for occupant protection laws were modeled in two stages. They are the product of the percentage increase in usage and the percent effective against fatalities when used. Our effectiveness estimates for these laws are:

(6) For primary safety belt laws, an 8% reduction in fatalities from a systematic review (Dinh-Zarr TB,. Sleet DA, Shults RA, et al., 2001). As a check on that estimate, the same meta-analysis estimates a primary law raises belt use by an average of 14 percentage points. With roughly 45% belt effectiveness across seating positions (Glassbrenner and Starnes, 2009), that suggests fatalities would be reduced by 6.3% (45% effectiveness * 14% belt use increase).

(7) Secondary safety belt laws. A 33 percentage point increase in use from the meta-analysis by Dinh-Zarr TB,. Sleet DA, Shults RA, et al. (2001). The estimated reduction in occupant fatalities (used in our analysis) is 15% (45% effective * 33% rise in use). The meta-analysis, however, finds only a 9% fatality reduction actually occurs, a number we used in sensitivity analysis. The smaller reduction suggests that airbags reduce the safety gains from belt use, some risk compensation is occurring with people trading restraint benefits for higher speeds, and/or those who laws induce to buckle up are occupants with below-average fatality risks.

(8) Motorcycle helmets from Deutermann (2004) which estimates that helmets reduce fatality risk by 37%. Motorcycle helmet laws consistently raise helmet usage by 40 to 50 percentage points (Ulmer and Preusser, 2003). With a conservative 40 percentage point rise, the fatality reduction is 14.8% (40% * 37%).

(9) Booster seat laws from Farmer, Howard, Rothman, et al. (2009) which estimates a 20% reduction in fatalities of front seat occupants ages 4–8 and a 38% increase in seat use in potentially fatal crashes. Another evaluation of booster seat use using on-site crash investigation data found that children 4 to 7 in States with booster seat laws were 39% more likely to be in appropriate restraints than in States without these laws (Winston, Kallan, Elliott, et al., 2007). Observational studies found laws were associated with a more modest 9% to 15% surge in booster seat use.

We were unable to estimate the savings from some laws. We could not estimate the usage increase for laws that closed gaps in child safety seat laws. We lacked effectiveness estimates for laws restricting teen cell phone use while driving and for impaired driving laws adopted by just one or two States.

Fatality Reductions

We computed the fatality reductions resulting from the laws state by state and year by year. If a law was in effect in a state in a given year, we computed the associated fatality reduction as

| (1) |

where F is the number of fatalities in state y and E is the effectiveness of the law (Glassbrenner and Starnes, 2009). As appropriate, we applied this formula to all fatalities or to fatalities among targeted subsets like motorcyclists or children aged 5–9.

When multiple impaired driving laws passed, we used a multiplicative formula (Glassbrenner and Starnes, 2009) to compute combined effectiveness as 1 − .(1 – Ei) where Ei is the effectiveness of the ith law. So, for example, if a state implemented an administrative license revocation law laws and a 0.08 maximum driver blood alcohol content (BAC) law, the combined effectiveness in equation 1 would be 1 – (1- 0.065 effective) * (1- 0.145 effective) = 0.20. This formula assumes the second law only would reduce fatalities not already prevented by the first law. As discussed further below, we applied the effectiveness estimates to fatality counts in all alcohol-involved crashes with sensitivity analysis to crashes where drivers were above a legislated BAC.

Cost Savings

We made the somewhat shaky assumptions that the percentage reduction in crash costs would mirror the fatality reduction and conservatively, that the laws would not affect property damage costs. We started from crash costs computed at a 4% discount rate for 1990 (Miller and Blincoe, 1994), 1993 (Miller, Lestina and Spicer, 1998; using an unpublished sensitivity analysis at a 4% discount rate), 1994 (Blincoe, 1996), 1999–2001 (Zaloshnja, Miller, Council, et al. 2006), 2006 (Zaloshnja and Miller, 2009), and 2005–2008 (an unpublished estimate we ran for this paper). By interpolating costs for the unpublished years, we estimated total crash costs by cost category from 1990–2009. The costs were built from NHTSA’s estimates of cost per crash. They include medical, other resource, and work loss costs, as well as the value of pain, suffering, and lost quality of life. We applied the payer matrix from Blincoe, Seay, Zaloshnja, et al. (2002) to the cost estimates.

RESULTS

Over the 20 year period, the 50 States and the District of Columbia passed at least 330 traffic safety laws. As Table 1 shows, the total includes 113 occupant protection laws, 141 impairing driving laws, and 76 other teen driving laws. Due in part to legislated Federal incentives, virtually every State implemented a booster seat use law, a 0.08 maximum driver blood alcohol level, zero tolerance for alcohol for drivers under 21, and some type of nighttime driving or passenger restriction for young novice drivers. Some States tightened their graduated licensing laws two and even three times. A fairly steady flow of road safety laws became effective each year (Figure 1).

Table 1.

State and District of Columbia highway safety laws passed in 1990 to 2009

| Type of Law | # of States | # of Laws |

|---|---|---|

| State Laws Passed | 51 | 330 |

| Occupant Protection | 51 | 113 |

| Secondary Safety Belt | 18 | 18 |

| Primary Safety Belt | 24 | 24 |

| Booster Seat | 48 | 50 |

| Other Child Occupant Protection | 14 | 17 |

| Motorcycle Helmet | 4 | 4 |

| Impaired Driving | 51 | 141 |

| 0.08 Maximum BAC | 48 | 48 |

| Zero Tolerance for Youth | 50 | 55 |

| Administrative License Revocation/Per Se | 18 | 19 |

| Mandatory Ignition Interlock | 3 | 3 |

| Other | 12 | 16 |

| Other | 50 | 76 |

| Graduated Driver Licensing | 50 | 71 |

| Teen Cell Phone Restriction | 5 | 5 |

| State Law Repeals Averted or Delayed | 16 | 18 |

| Motorcycle Helmet | 16 | 18 |

N/A = Savings not available.

Figure 1.

Number of State highway safety laws added by year they became effective

Lobbying also kept motorcycle helmet use mandates from being repealed in 16 states. Other relevant Federal laws were an airbag mandate, the 1991 surface transportation act reauthorization that combined vehicle safety, traffic safety and roadway safety issues for the first time, and a cornucopia of laws governing truck safety.

Lives Saved

The laws we were able to evaluate saved an estimated 120,000 lives (Table 2). That equals an average crash fatality reduction of 14.5% over the past 20 years.

Table 2.

Crash fatality reductions in 1990–2009 resulting from selected State laws and the Federal airbag mandate

| Laws | Fatalities Prevented | % Reduction in Related Fatalities* |

|---|---|---|

| Safety Belts | 32,700 | 5% |

| Airbags | 30,200 | 5% |

| Booster Seats | 300 | 19% |

| Motorcycle Helmets | 3,000 | 4.5% |

| Impaired Driving | 52,100 | 16% |

| Graduated Licensing | 3,100 | 6% |

| TOTAL | 120,000 | 14.5% |

Computed as fatalities averted/fatalities remaining

The largest life-saving benefits sprang from impaired driving laws. Airbag and belt use laws also accounted for large shares of the savings. Booster seat, graduated driver licensing, and helmet laws had more modest impacts because they affect narrow subpopulations.

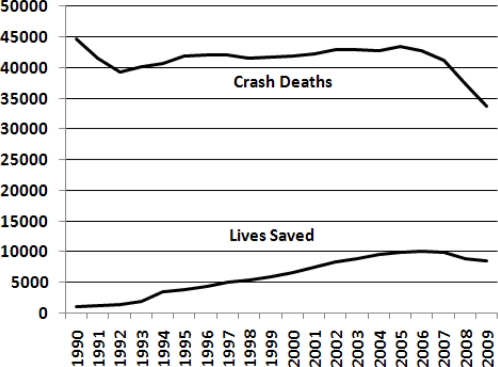

The life-saving benefits accelerated as the number of laws in force grew (Figure 2). By 2009, the laws resulted in 25% fewer crash fatalities. The reduction in crash deaths (and driving) associated with the recession of 2008–2009 caused a presumably temporary downturn in lives saved by the laws (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Growth over time in the percentage fatality reduction due to highway safety laws passed in 1990–2009

Figure 3.

Lives saved by highway safety laws passed in 1990–2009, by year

The estimate of lives saved was moderately sensitive to the effectiveness estimate used for secondary belt laws and to the choice to apply the impaired driver effectiveness estimates to all alcohol-related crashes rather than those with drivers above the legal limit. With either alternative calculation, estimated fatality savings over the 20 year period would decline by 7,000–8,000 (6%–6.5%).

Cost Savings

The laws reduced insurance claims payments and claims processing costs by more than $210 billion (Table 3). They saved government an estimated $42 billion, with Medicaid and Medicare claims payments dominating the government savings.

Table 3.

Cost savings by payer resulting from highway safety laws passed or kept in force through advocacy, 1990–2009 (inflated to 2010 dollars)

| Payer | Savings |

|---|---|

| Auto Insurance | $128 billion |

| Workers’ Compensation Insurance | 8 billion |

| Private Health Insurance | 70 billion |

| Life Insurance | 5 billion |

| Sub-total: Private Insurance | $211 billion |

| Government | 42 billion |

| Employers | 8 billion |

| Taxpayers | 343 billion |

| Total Economic Costs | $604 billion |

| Quality of Life (Taxpayers) | $758 billion |

| GRAND TOTAL | $1,362 Billion |

Overall, the monetary cost savings exceeded $600 billion including $135 billion in medical care spending (not tabulated). If we add the value of lost quality of life, the savings were more than $1.3 trillion.

The reductions grew annually because the fatality and crash reductions rose. In 2009 alone, the laws saved an estimated $125 billion including $12.5 billion in medical spending and $4 billion in government cost savings.

DISCUSSION

The 330 State laws passed between 1990 and 2009 are an average of 6.5 laws per State. On average, States passed a new highway safety law every 3 years. Often States passed a cluster of laws at once. Nevertheless, the steady stream of laws required sustained advocacy and enlistment of elected officials who became lasting champions of road safety.

New traffic safety laws saved an estimated 120,000 lives over the past 20 years. By 2009, they reduced crash deaths by 25%. Annual crash costs including the value of lost quality of life currently total about $500 billion. Over the 20 year period, the reduction due to safety legislation – and the advocacy that prompted its passage – exceeded 2.5 full years of crash costs.

This analysis has obvious limitations. Some relate to the quality and scope of available effectiveness data. Evaluations only existed for 90% of the state laws and none of the Federal truck safety laws. In general, we had to assume that the effects on fatalities were proportional to the effects on fatal crashes.

None of our State estimates consider how differences in enforcement and other factors will cause effectiveness to vary between States. It was difficult to evaluate graduated licensing laws that did not match the model law or incrementally changed to match the model. Also, the Dinh-Zarr, et al. (2001) effectiveness estimate for primary belt laws may not match recent experience because a higher baseline usage rate means a law is likely to produce less new users, but conversely, the hard core resisters who do convert are likely to include many high-risk drivers.

We were unable to overlay the effectiveness estimates for interacting occupant protection and driver behavior laws. That probably caused some modest overestimation of the fatality reduction. A major barrier to an overlay arises because impaired drivers face above-average risks but at the same time, laws may be less likely to induce them to use safety belts or motorcycle helmets.

Despite these limitations, the estimated fatality impact should be a conservative lower bound. The analysis is stronger because it does not estimate the savings with a times series regression. We estimated the fatality reductions each year from the number of fatalities in that year, not from the trend in fatalities over time. Therefore, we correctly project less lives are saved in years when economic conditions reduced driving and consequently the number of road deaths. Avoiding a regression approach also means our estimates are not confounded with fatality reductions due to improved vehicle crashworthiness, vehicle occupant protection, road design, or infrastructure.

Our cost savings estimates are less reliable than the estimates of lives saved. They rely on the questionable assumption that nonfatal injury crash costs fell by the same percentage as fatalities. That assumption is reasonably well-supported for crashes with serious injury but not for crashes involving only minor injury. Fatal and serious crashes, however, account for more than 85% of all injury crash costs. At least partially offsetting the aggressive assumption about minor injuries, we assumed property damage costs (27% of economic costs and 14% of total crash costs) would not be affected by the laws. Thus, the cost estimate would not be hugely affected by different assumptions about the effects on minor crashes and property damage.

CONCLUSION

The results convincingly demonstrate that legislative action and the advocacy that spawns it can have a major influence on highway safety. They are spark plugs in the safety engine.

The research community plays a critical role in the advocacy process. Indeed, research is a pedestal of successful legislative advocacy. In the words of Millie Webb (2001), a former president of MADD, “In order to advocate effectively for lifesaving legislation, advocates must have clear and compelling scientific evidence to provide a basis for policy change.”

That evidence helps to set the advocacy agenda. It provides the facts needed to overcome well-funded efforts to stall or reject controversial laws that can yield large benefits. “Traffic safety advocates rely on research to advance” their “cause and provide ... credibility ... with policymakers and the media.” They “weave research findings into every piece of” their “advocacy efforts.” As this papers shows, those advocacy efforts pay healthy legislative and safety dividends.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was funded in part by Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety and by the Children’s Safety Network, U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration. Neither funder reviewed this paper.

REFERENCES

- Baker SP, Chen LH, Li G. National Evaluation of Graduated Driver Licensing Programs (DOT HS 810 614) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blincoe LJ. The Economic Costs of Motor Vehicle Crashes, 1994 (DOT HS 808 425) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Blincoe LJ, Seay A, Zaloshnja E, et al. The Economic Impact of Motor Vehicle Crashes, 2000 (DOT HS 809 446) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; May, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Deutermann W. Motorcycle Helmet Effectiveness Revisited Report (HS 809 715) Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Adminstration; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh-Zarr TB, Sleet DA, Shults RA, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to increase the use of safety belts. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(4 Suppl):48–65. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas WO. The Court Years, 1939–1975: The Autobiography of William O. Douglas. New York: NY: Random House; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer P, Howard AL, Rothman L, et al. Booster seat laws and child fatalities: A case–control study. Inj Prev. 2009;15(5):348–350. doi: 10.1136/ip.2008.021204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell JC, Fisher DA, Voas RB, et al. The relationship of underage drinking laws to reductions in drinking drivers in fatal crashes in the United States. Accid Anal Prev. 2008;40:1430–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassbrenner D, Starnes M. Lives Saved Calculations for Seat Belts and Frontal Air Bags (DOT HS 811 206) Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Adminstration; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Haddon W., Jr On the escape of tigers: An ecologic note. Am J Public Health. 1970;60:2229–2234. doi: 10.2105/ajph.60.12.2229-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M. Lower legal blood alcohol limits for young drivers. Public Health Rep. 1994;109(6):739–744. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein TM. Changes in Alcohol-Involved Fatal Crashes Associated with Tougher State Alcohol Legislation (DOT HS 807 511) Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lacey JH, Jones RK, Stewart JR. Cost-benefit analysis of administrative license suspensions (DOT HS 807 689) Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; Jan, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Miller TR, Lestina DC, Spicer RS. Highway crash costs in the United States by driver age, blood alcohol level, victim age, and restraint use. Accid Anal Prev. 1998;30(2):137–150. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(97)00093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration . Traffic Safety Facts 2007: A Compilation of Motor Vehicle Crash Data from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System and the General Estimates System (DOT HS 811 002) Washington, DC: National Center for Statistics and Analysis, U.S. Department of Transportation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration . Lives Saved in 2009 by Restraint Use and Minimum-Drinking-Age Laws (DOT HS 811 383) Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford University Press . Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ross HL. Administrative license revocation in New Mexico: An evaluation. Law and Policy. 1987;9(1):5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Shults RA. Drivers aged 16 or 17 years involved in fatal crashes-United States, 2004–2008. JAMA. 304(21):2355–2377. [Google Scholar]

- Shults RA, Elder RW, Sleet DA, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce alcohol-impaired driving. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(4 Suppl):66–88. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tippetts AS, Voas RB, Fell JC, et al. A meta-analysis of .08 BAC laws in 19 jurisdictions in the United States. Accid Anal Prev. 2005;37(1):149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmer RG, Preusser DF. Evaluation of the Repeal of Motorcycle Helmet Laws in Kentucky and Louisiana (DOT HS 809 602) Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Voas RB, Marques PR, Tippetts AS, et al. The Alberta Interlock Program: The evaluation of a province-wide program on DUI recidivism. Addiction. 1999;94(12):1849–1859. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9412184910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voas RB, Tippetts AS, Fell J. Assessing the effectiveness of minimum legal drinking age and zero tolerance laws in the United States. Accid Anal Prev. 2003;35(4):579–587. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(02)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb M. Research as an advocate's toolkit to reduce motor vehicle occupant deaths and injuries. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(4(Supplement 1)):7–8. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston FK, Kallan MJ, Elliott MR, et al. Effect of booster seat laws on appropriate restraint use by children 4 to 7 years old involved in crashes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;(161):270–275. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zador PK, Lund AK, Field M, et al. Alcohol-Impaired Driving Laws and Fatal Crash Involvement. Washington, DC: Insurance Institute for Highway Safety; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Zaloshnja E, Miller TR, Council F, et al. Crash costs in the United States by crash geometry. Accid Anal Prev. 2006;38(4):644–651. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaloshnja E, Miller TR. Costs of crashes related to road conditions, United States, 2006. Ann Adv Automot Med. 2009;53:141–153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]