Abstract

This paper describes the injury patterns of pedestrians involved in collisions with cars, compares them with other road casualties and estimates the possible effect of car front profile on injury location. Injury patterns were identified using the Rhône Road Trauma Registry which covers all the casualties resulting from crashes in the Rhône Département (1.6 million inhabitants) who seek medical care in health facilities. Fatality rates were estimated from national police reports for the same years (1996–2007), and the two data sources were linked to obtain information on the front profile of the striking car. As with all groups of road users, most of the pedestrians involved in car crashes were young. However elderly people were overrepresented when the size of the exposed population was taken into account. The most frequently injured body regions were the lower extremities (50% of victims), the head/face/neck (38%) and the upper extremities (27%). Pelvic injuries were much more common for women. The most severe injuries (AIS4+) were mostly to the head and thorax, for all groups of road users. However, pedestrians sustained twice as many head injuries as thoracic injuries. When the front profiles were grouped together according to the most common car types in Europe, the risk of being killed was higher for MPVs. More specifically, the risk of sustaining an AIS2+ thoracic injury was higher in a collision with an MPV. Our study confirms that it is quite justified for the tests based on European Enhanced Vehicle-Safety Committee guidelines to be focused on the head and the lower extremities. However, no test procedure exists for thoracic injuries, which is the body region with the second highest number of severe or fatal injuries.

INTRODUCTION

The most recent WHO Global Status Report (Naci, Chilsholm and Baker 2009; WHO 2009) states that in low-income countries, pedestrians account for 45% of road fatalities, i.e. an annual number of over 200,000, and that in high-income countries pedestrians account for 18% of road fatalities, i.e. over 22,000 annually. These major differences are partly due to differences in exposure, as in some countries a major proportion of trips are made on foot. They also reflect differences in the safety of road user behaviour, in particular the extent to which road users take account of other persons using the road space. The existence in developed countries of specific pedestrian facilities such as crossings or sidewalks could also explain some of these differences. In all countries, the majority of pedestrians injured in a road traffic accident are struck by a motor vehicle, usually a car. The potential benefits of developing active and passive countermeasures for cars are thus clear.

The first objective of this research is to identify the injuries sustained by pedestrians in collisions with cars in order to evaluate the suitability of the test methods developed by the European Enhanced Vehicle-Safety Committee (EEVC 2002). The second objective is to see whether their location and severity are linked to the shape of the striking vehicle’s bonnet. This is prompted by two kinds of studies which have shown that the shape of the vehicle front may affect injury outcomes: Studies based on real world crash data, showing that injury outcomes differ depending on the striking vehicle (Fredriksson, Rosen and Kullgren 2010; Henary, Crandall, Bhalla et al. 2003; Roudsari, Mock and Kaufman 2005; Zhang, Cao, Hu et al. 2008), and studies based on in-depth studies or experimental data, describing the possible influence of wrap-round distances, contact points on the bonnet surface or bumper height on injury patterns (Fildes, Gabler, Otte et al. 2004; Matsui 2005; Mizuno and Ishikawa 2001; Otte and Haasper 2007; Van Rooij, Bhalla, Meissner et al. 2003).

METHODS

This analysis is principally based on data from the Rhône Département Road Trauma Registry. This Registry contains medical data on all the individuals who sustain injuries in road traffic accidents that occur in the Rhône Département. The data is collected in all the departments that administer care to road traffic accident casualties (from emergency departments to rehabilitation departments and including public and private care facilities). In addition to details about the general characteristics of the accident casualties (and in particular whether or not they were pedestrians) and a few details about the circumstances of the accident, the register contains full descriptions of the injuries sustained by each subject. These injuries are each coded using the Abbreviated Injury Scale 1990 (AAAM (Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine) 1994).

Following a brief comparison between crash-involved pedestrians and other crash-involved road users, the greater part of this paper will be concerned with a detailed description of the injuries sustained by pedestrians. The first part of our analysis involved the 10,703 pedestrians who were injured or killed in an accident involving a vehicle between 1996 and 2007. The analysis was then restricted to the 8,566 pedestrians who were struck by a car. The 47 children of under two years of age were then excluded, because of their low number and their unclear status as pedestrians (they are either carried or in a pushchair, etc.). Last, the detailed injury descriptions covered only the 3,289 pedestrians who had sustained at least one AIS 2 (MAIS 2+) injury.

We have attempted to identify the influence of age and gender on injury severity and location. With regard to regulatory measures concerning vehicles, the injuries to body regions such as the head, pelvis, knee and leg were described in full. The location of injuries was then examined in relation to the shape of the bonnet on the striking vehicle.

The injury tables show the proportion of casualties with at least one injury of AIS2 or greater (AIS2+) for each of the body regions defined in the AIS code. This means that a subject with two injuries featured twice in the tables that set out the injured body regions if the injuries were to different body regions but only once if the injuries were to the same body region.

The second part of the analysis uses data from national police accident reports for the same years. The large sample size (N=204,990) meant the proportion of fatalities among those sustaining injuries (i.e. the lethality) could be used as a severity criterion. Lethality estimates were thus derived according to the type of striking vehicle, to the part of the car striking the pedestrian or to the type of car.

A large number of the records (N=92,564) contained the Vehicle Identification Number of the car involved in the pedestrian accident which made it possible to construct two typologies for most of cars (N=72,134):

- One which classified cars in the conventional way, according to their market segment (supermini, small family car, large family car and multi purpose vehicles, i.e. MPV) as done by EuroNCAP,

- Another which distinguished between the front profiles of the vehicles on the basis of the length of the bonnet, according to whether this short, medium or long), as well as the category that consists of MPVs with “sloping bonnets”. These categories were therefore very much based on the theoretical ability of the front profile of the vehicle to mitigate an impact. They were defined by the motor vehicle part manufacturers who were partners in the project.

In this way we investigated the location of injuries with reference to the type of bonnet on the striking vehicle. As the Registry does not contain any information about the make and type of the vehicle, the records it contains were linked to those in the police data. This process considerably reduced the size of the sample, for two main reasons. The first is that the police data are not exhaustive for various reasons that have been explained elsewhere (Amoros, Martin, Lafont et al. 2008; Amoros, Martin and Laumon 2006); the second is that the two databases do not share a common identifier. The records in the two databases were deemed to refer to the same casualties when the data on the date, time and location of the crash, the date of birth and gender of the road user and the type of road user corresponded. The location of injuries with reference to the type of bonnet on the striking vehicle can only thus be idenified for 940 MAIS2+ pedestrians.

In addition to the injury tables, the effects of variables such as age, gender, and type of vehicle were tested using logistic regression. The effect of each variable was tested by means of a maximum likelihood ratio test at the 5% significance level. The relative risks were estimated using odds ratios (OR) with their 95% confidence intervals. An OR was judged to be significantly different from 1 when its confidence interval did not include the value 1. The calculations were performed with version 9.2 of the SAS software (SAS 2008).

RESULTS

The Rhône Registry contains a total of 115,501 casualties with AIS 1+ injuries sustained between 1996 and 2007. Pedestrians are the fourth largest group among these casualties (9.3%), after car occupants (49.6%), motorized two-wheeler users (20.7%) and cyclists (13.5%). Lethality is higher for pedestrians (2.0%) compared to other road casualties.

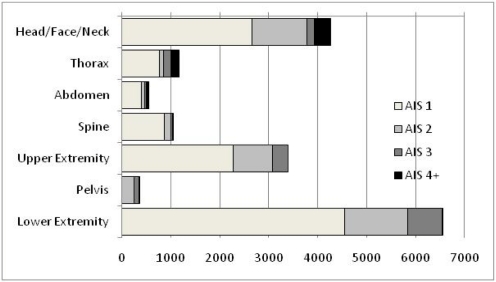

Figure 1 shows the number of casualties with at least one injury to the body region in question, distinguishing between AIS 1, 2, 3 and 4 and greater injuries. The most common pedestrian injuries were to the lower extremities, with the head in second place. These were followed by upper extremity injuries. The most severe injuries (AIS 4+) were to the head and thorax for all road user types. Pedestrians nevertheless sustained twice as many severe injuries to the head as to the thorax whereas these injuries were observed in similar numbers among motorists and motorized two-wheeler users.

Figure 1:

Pedestrian injury pattern. Rhône Trauma Registry, 1996–2007 (N=10,703)

The characteristics of the crash-involved pedestrians

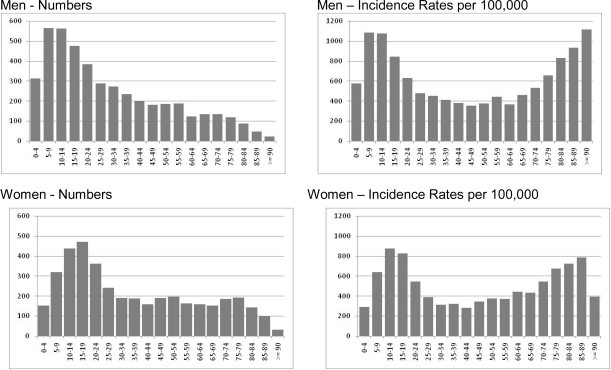

Figure 2 shows the observed numbers (on the left) and the estimated incidence rates (on the right) obtained by dividing the number of casualties by the Département’s population belonging to each age class and gender.

Figure 2 :

Age distribution for each gender of the numbers (on the left) and incidences per 100,000 population in the Rhône Département (on the right). Rhône Trauma Registry 1996–2007.

For pedestrian casualties, the most represented age groups were 5–14 year-olds among males and 10–19 year-olds among females. As with other road user categories, the injured pedestrians were predominantly young and more frequently male. In terms of incidence rates, the oldest age category, namely the over 70s, was very highly represented, to the extent they accounted for over 50% of casualties among the over 85 year-olds.

Table 1 shows that the severity of pedestrian injuries increased with age, particularly after 64 years, both in terms of lethality and the percentage of MAIS 2+ casualties.

Table 1:

Age distribution of the number of pedestrians involved in collisions with a car. Rhône Trauma Registry 1996–2007.

| Age | N | Col % | Lethality | MAIS2+ (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | 47 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 23.4 |

| 2–4 | 419 | 4.9 | 1.2 | 28.2 |

| 5–10 | 1062 | 12.4 | 0.4 | 33.9 |

| 11–16 | 1195 | 14.0 | 0.4 | 34.1 |

| 17–39 | 2740 | 32.0 | 0.6 | 30.3 |

| 40–64 | 1751 | 20.4 | 2.2 | 44.3 |

| > 64 | 1352 | 15.8 | 5.7 | 59.1 |

| Total | 8566 | 100 | 1.7 | 38.5 |

As can be seen in Table 2, the most affected body regions were, in order, the lower extremities (50% of casualties), the head/face/neck zone (38%) and the upper extremities (27%).

Table 2 :

The nature of the injury, the injured body region part of body region among pedestrian casualties of over 2 years of age (both survivors or fatalities) with at least one AIS2+ injury. Rhône Trauma Registry 1996–2007. (N=3289)

| Injured body region | Number of casualties with at least one AIS 2+ injury | % victims | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head, face or Neck | 1252 | 38.07 | |

| Loss of consciousness | 839 | 25.51 | |

| Cranium | 171 | 5.2 | |

| Intracranial injury | 267 | 8.12 | |

| Neck | 6 | 0.18 | |

| Scalp, face, eyes | 178 | 5.41 | |

| Thorax | 281 | 8.54 | |

| Rib cage | 196 | 5.96 | |

| Sternum | 19 | 0.58 | |

| Diaphragm | 2 | 0.06 | |

| Respiratory tract | 99 | 3.01 | |

| Circulatory system | 8 | 0.24 | |

| Œsophagus | 2 | 0.06 | |

| Abdomen | 98 | 2.98 | |

| Genitourinary system | 30 | 0.91 | |

| Digestive system | 39 | 1.19 | |

| Spleen | 36 | 1.09 | |

| Spine | 139 | 4.23 | |

| Cervical Spine | 50 | 1.52 | |

| Thoracic Spine | 47 | 1.43 | |

| Lumbar Spine | 55 | 1.67 | |

| Upper extremities | 870 | 26.45 | |

| Shoulder or arm | 512 | 15.57 | |

| Elbow or forearm | 275 | 8.36 | |

| Wrist or hand | 121 | 3.68 | |

| Pelvis | 289 | 8.79 | |

| Lower extremities | 1630 | 49.56 | |

| Hip | 84 | 2.55 | |

| Thigh | 117 | 3.56 | |

| Hip/Thigh Other | 36 | 1.09 | |

| Knee | 463 | 14.08 | |

| Leg | 657 | 19.98 | |

| Ankle | 282 | 8.57 | |

| Foot | 159 | 4.83 | |

The most frequently injured parts of the lower extremities were the leg (20%) and knees (14%). Loss of consciousness was the commonest head injury (25%). The pedestrians who sustained injuries to the upper extremities most often had shoulder/arm injuries (16%). The relatively high proportion of pelvic injuries (9%) is also noteworthy. With regard to nature of the injuries, 73% of the pedestrian casualties who had sustained at least one AIS 2 injury had a fracture.

On average, males were more seriously injured, sustaining significantly more internal organ injuries (OR=1.70; 95% C.I.: 1.35–2.04). They more frequently had injuries to the head/face/neck zone (OR=1.35; 95% C.I.: 1.16–1.56), or the thorax (OR=2.08; 95% C.I.: 1.59–2.70), and the legs (OR=1.45; 95% C.I.: 1.22–1.72).

Females, in contrast, sustained more injuries to the upper extremities (OR=1.28; 95% C.I.: 1.09–1.50), the knees (OR=1.36; 95% C.I.: 1.11–1.67), and, particularly, the pelvis, for which the risk was twice as high as for males (OR=2.39; 95% C.I.: 1.84–3.11).

Taking the 17–39 year-olds as a reference group, the risk of sustaining at least one fracture was 1.7 times higher for the 40–64 year olds (OR=1.70; 95% C.I.:1.36–2.11), and 2.6 times higher for persons of 65 years of age and over (OR=2.57; 95% C.I.: 2.03–3.25). The risk of an internal organ injury, with or without a fracture, was also higher for the older age groups. The frequency of AIS 2+ injuries to the thorax, spine, pelvis and knees was significantly higher among pedestrians of over 40 years of age. The youngest pedestrians (2–4 year-olds) had three times more abdominal injuries than the 17–39 year-olds (OR=3.37; 95% C.I.: 1.54–7.37). The under 17 year-olds had fewer spinal injuries. The injuries to the leg sustained by this group (particularly those aged under 11 years) were more frequently to the thigh and less frequently to the knee.

We can make the following observations about the body regions that are targeted by regulatory test procedures:

- Most of the AIS 2+ injuries to the head other than mere loss of consciousness, involved the brain (15%), followed by the cranium (5%). The commonest injury was subarachnoid haemorrhage.

- The commonest pelvic injury was a closed (simple) fracture (5%). The probability of sustaining a pelvic injury increased markedly with age after 40 years.

- The commonest thigh injury was an open/displaced/multifragmentary fracture. The probability of sustaining a thigh injury was considerably higher between 2 and 10 years of age.

- The most frequent knee injury was a fractured tibial plateau, followed by a sprain. Tibial plateau fractures were more frequently observed among males, but this was not the case for sprains. The proportion of knee injuries involving a bone injury was higher for males and increased with age for both genders. The majority of ligament injuries were observed among the young, which may be due to the fact that ligament injuries could be less often coded in case of fracture. It is also possible that the older persons, who more often suffer from fracture injuries, sustain fewer ligament injuries because a fracture reduces the stresses on the ligaments.

- With regard to the leg, the commonest injury was a fracture of the fibula (16%). Males more frequently sustained a tibial shaft fracture.

Fatality rates from police reports

Between 1996 and 2007, 204,990 pedestrian casualties were listed in the national police accident reports. Table 3 displays the lethality according to the type of vehicle that struck the pedestrian.

Table 3 :

Distribution of crash-involved pedestrians and lethality according to the type of striking vehicle. Accidents involving a single vehicle and a single pedestrian. National police reports 1996–2007.

| Type of vehicle striking the pedestrian | N | Col % | Lethality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclist | 3,334 | 1.6 | 1.0 |

| Motorized two wheeler | 27,205 | 13.3 | 2.3 |

| Car | 154,704 | 75.5 | 4.2 |

| Light Utility Vehicle | 8,136 | 4.0 | 5.4 |

| Truck | 3,688 | 1.8 | 24.8 |

| Other | 7,923 | 3.9 | 6.0 |

| Total | 204,990 | 100.0 | 4.4 |

It is interesting to note that lethality was very much higher in the case of a collision with a truck than a car, and slightly higher in the case of a collision with a commercial vehicle category, which mostly consists of minivans whose front profile is fairly vertical.

In addition, when the vehicle identification number was correctly recorded in police reports, Table 4 shows, in the case of cars only, the part of the vehicle on which the main impact occurred.

Table 4:

Part of the car striking the pedestrian and lethality. National police reports 1996–2007.

| Part of the car striking the pedestrian | N | Col % | Lethality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Front | 45,949 | 49.6 | 3.6 |

| Right front | 18,708 | 20.2 | 6.7 |

| Left front | 11,597 | 12.5 | 5.9 |

| Rear | 6,369 | 6.9 | 1.9 |

| Side impact | 4,776 | 5.2 | 2.7 |

| Other | 5,165 | 5.6 | 2.1 |

| Total | 92,564 | 100.0 | 4.3 |

As one would expect, most of the impacts involved the front of the vehicle, but it is interesting to note that the lethality was significantly higher in the case of an off-centre than a central frontal impact.

With regard to the association between the type of car and the injuries sustained by pedestrians, Table 5 sets out the estimated odds ratios adjusted for age and gender, and for some variables that are linked to impact severity for the two selected groupings of cars. The vehicle registration year is taken as a proxy for the design year.

Table 5:

Estimated adjusted odds ratios according to type of car (on the left) and front profile (on the right). National police reports 1996–2007 (N=72,134)

| Type of car | col% | Lethality | Adjusted OR* | 95% C.I. | Type of front profile (bonnet) | col% | Lethality | Adjusted OR* | 95% C.I. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supermini | 53.0 | 3.8 | 1 | Short | 1.1 | 2.8 | 0.75 | (0.47–1.19) | ||

| Small Family Car | 27.6 | 4.6 | 1.17 | (1.07–1.28) | Medium | 68.7 | 4.3 | 1 | ||

| Large Family Car | 14.4 | 4.5 | 1.17 | (1.05–1.31) | Long | 25.2 | 3.7 | 0.92 | (0.84–1.01) | |

| MPV | 5.0 | 4.9 | 1.38 | (1.16–1.63) | Sloping bonnet | 5.0 | 4.9 | 1.24 | (1.05–1.47) | |

| Total | 100.0 | 4.2 | Total | 100.0 | 4.2 | |||||

adjusted for pedestrian gender and age, road category, day of the week, year of crash and car registration year

The risk of being killed was significantly higher in the case of an impact with an MPV/Sloping bonnet, in comparison both with superminis when vehicle type was considered (on the left), and with cars with a “medium bonnet” (on the right of the table). It should be noted that the “short bonnet” category has the lowest lethality, but the number of vehicles was very small.

The location of injuries according to the type of car and its front profile

The injury descriptions that follow relate only to the 940 casualties in the Registry who had sustained at least one AIS 2+ injury and for whom we were able to determine the type of striking vehicle and its front profile by making a linkage with police data.

Table 6 sets out the estimated odds ratios for each body region adjusted for age and gender, using the same vehicle and front profile typologies as in the preceding table.

Table 6 :

Injury risk according to body region and type of car or type of front profile, with Odds Ratio estimates, adjusted for age and gender, for each body region obtained by logistic regression. Linkage between the Rhône Registry and National Police Reports 1997–2008 (N=940)

| Type of car | % of casualties with at least one AIS2 + injury | OR | 95% C.I. | P-value | Type of front profile (bonnet) | % of casualties with at least one AIS2 + injury | OR | 95% C.I. | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head/Face/Neck | NS | NS | |||||||||

| Supermini | 41.2% | 0.77 | (0.56–1.05) | Short | 40.0% | 0.97 | (0.38–2.43) | ||||

| Small Family car | 46.9% | 1 | Medium | 42.0% | 1 | ||||||

| Large Family Car | 41.1% | 0.76 | (0.50–1.17) | Long | 45.1% | 1.18 | (0.87–1.60) | ||||

| MPV | 40.3% | 0.76 | (0.43–1.35) | Sloping bonnet | 40.3% | 0.96 | (0.56–1.65) | ||||

| Thorax | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| Supermini | 8.5% | 0.62 | (0.37–1.01) | Short | 10.0% | 0.85 | (0.18–3.95) | ||||

| Small Family car | 13.0% | 1 | Medium | 9.3% | 1 | ||||||

| Large Family Car | 9.9% | 0.72 | (0.36–1.43) | Long | 11.8% | 1.19 | (0.73–1.93) | ||||

| MPV | 24.2% | 2.41 | (1.17–4.95) | Sloping bonnet | 24.2% | 3.42 | (1.75–6.70) | ||||

| Abdomen | NS | NS* | |||||||||

| Supermini | 3.3% | 0.67 | (0.31–1.46) | Short | 0. | 0 | (0.00–4.40) | ||||

| Small Family car | 4.7% | 1 | Medium | 3.8% | 1 | ||||||

| Large Family Car | 2.1% | 0.42 | (0.11–1.52) | Long | 3.3% | 0.86 | (0.33–2.03) | ||||

| MPV | 3.2% | 0.65 | (0.14–3.02) | Sloping bonnet | 3.2% | 0.85 | (0.09–3.60) | ||||

| Spine | NS | NS | |||||||||

| Supermini | 7.2% | 1.79 | (0.89–3.61) | Short | 5.0% | 0.88 | (0.11–6.99) | ||||

| Small Family car | 4.3% | 1 | Medium | 4.7% | 1 | ||||||

| Large Family Car | 3.5% | 0.80 | (0.27–2.38) | Long | 8.5% | 1.69 | (0.94–3.06) | ||||

| MPV | 6.5% | 1.48 | (0.45–4.89) | Sloping bonnet | 6.5% | 1.28 | (0.43–3.61) | ||||

| Upper extremities | NS | NS | |||||||||

| Supermini | 25.7% | 0.77 | (0.55–1.08) | Short | 20.0% | 0.66 | (0.21–2.04) | ||||

| Small Family car | 30.7% | 1 | Medium | 26.8% | 1 | ||||||

| Large Family Car | 19.1% | 0.53 | (0.32–0.87) | Long | 24.8% | 0.85 | (0.60–1.20) | ||||

| MPV | 25.8% | 0.79 | (0.42–1.49) | Sloping bonnet | 25.8% | 0.95 | (0.52–1.73) | ||||

| Pelvis | NS | NS | |||||||||

| Supermini | 11.2% | 0.82 | (0.52–1.33) | Short | 5.0% | 0.41 | (0.05–3.19) | ||||

| Small Family car | 13.8% | 1 | Medium | 9.8% | 1 | ||||||

| Large Family Car | 7.8% | 0.57 | (0.27–1.18) | Long | 15.9% | 1.65 | (1.05–2.58) | ||||

| MPV | 11.3% | 0.79 | (0.33–1.94) | Sloping bonnet | 11.3% | 1.10 | (0.47–2.59) | ||||

| Lower extremities | NS | NS | |||||||||

| Supermini | 51.8% | 1.19 | (0.87–1.62) | Short | 45.0% | 0.70 | (0.28–1.71) | ||||

| Small Family car | 47.6% | 1 | Medium | 52.5% | 1 | ||||||

| Large Family Car | 51.8% | 1.17 | (0.77–1.78) | Long | 46.3% | 0.76 | (0.56–1.02) | ||||

| MPV | 50.0% | 1.07 | (0.61–1.87) | Sloping bonnet | 50.0% | 0.86 | (0.51–1.47) | ||||

univariate exact confidence limits

The only body region for which these analyses revealed a significant difference according to type of vehicle and front profile was the thorax.

Thus the risk of sustaining an AIS 2+ thoracic injury appeared to be significantly higher in the case of an impact with a MPV/sloping bonnet than a car with a “medium-length” bonnet (OR=3.42; 95% C.I.: 1.75–6.70) or a small family car (OR=2.41; 95% C.I.: 1.17–4.95). Moreover, we did not observe that the type of bonnet affected the percentage of casualties with fractures or internal organ injuries with or without a fracture.

DISCUSSION

Pedestrians are marked out from other crash-involved road users by their very high frequency of injuries to the lower extremities with the head/face/neck region zone coming in second position. These are followed by injuries to the upper extremities. The most severe (potentially fatal) AIS 4+ injuries are to the head and thorax for all types of road user. Pedestrians nevertheless sustain twice as many severe injuries to the head as to the thorax, while the risks of these types of injury are similar for motorists and users of motorized two-wheelers.

As with the other categories of road users, most crash-involved pedestrians are young. In terms of incidence rates, older road users (over 70 years of age) are highly represented, to the extent that more than 50% of casualties of over 85 years of age are pedestrians. The severity of pedestrian injuries increases with age, particularly over 64 years both in terms of lethality and the percentage of MAIS 2+ injuries.

In general, males are more severely and more often injured in road traffic accidents than females. This has already been observed in other studies (Assailly 1997; Fontaine and Gourlet 1997). However, in the case of car accidents, a comparison between drivers who are involved in the same accident has shown that the risk of being killed is higher for women when the configuration of the crash and the characteristics of the vehicles are taken into account (Martin and Lenguerrand 2008), as a result of women’s greater “fragility”. It is therefore surprising that male pedestrians are more severely injured than females. Part of the explanation for this doubtless lies in the behaviour of male pedestrians which means their accidents take place in circumstances that are associated with higher impact speeds. Some studies reveal an excess risk among young boys which is the result of their more impulsive behaviour and greater risk exposure (Assailly 1997; Fontaine et al. 1997; Lynam and Harland 1992).

The effect of age on injury severity, in particular the age-related increase in the percentage of fractures has been observed for all types of road user (Henary, Ivarsson and Crandall 2006). It is thus apparent for pedestrians over 40 and above all over 65 years of age, who are more frequently killed or seriously injured. In particular, they sustain more AIS 2+ injuries to the thorax, spine and pelvis. This is no doubt due to a reduction in their capacity to withstand impacts. This over-representation in pedestrian accidents when one takes account of the size of the population in each age group is primarily due to their higher exposure, particularly in the case of the oldest groups for whom walking is the most frequent transport mode, and perhaps also because of their poorer reflexes and slower speed when crossing a road (OCDE 1985).

Differences between populations, sampling and methodology aside, the injury descriptions of crash involved pedestrians we have given in this paper appear to be consistent with those reported in other studies (Demetriades, Murray, Martin et al. 2004; Kramlich, Langwieder, Lang et al. 2002; Mizuno et al. 2001; Peng and Bongard 1999). Demetriades and Schmucker, for example, highlight the high incidence of subarachnoid heamorrhage. among pedestrians with severe head injuries (Demetriades et al. 2004; Schmucker, Beirau, Frank et al. 2010).

With regard to the association between the type of vehicle and pedestrian injury patterns, we have considered two groupings in this study, one based on market segment and the other on the type of vehicle front, in particular the size of the bonnet. These two typologies coincide for MPVs, which both have sloping bonnets. MPVs are the only type of vehicle that differs significantly from the others. An analysis of the location of AIS 2+ injuries shows that the risk of sustaining an AIS 2+ thoracic injury is significantly higher (OR=3.4) in the case of an impact with a sloping bonnet than other types, while no significant difference is observed for other body regions, including the lower extremities. As with MVPs the pedestrian wrap-around distance on the car front tends to be different compared to other cars, direct contact with the thoracic region could be more frequent, which could partly explain the higher frequency and greater severity of thoracic injuries.

Of course, parameters that play a decisive role in the kinematics of the impact, such as impact speed (Helmer, Samaha, Scullion et al. 2010), the position of the pedestrian at the time of the impact and the point of impact are unknown and indubitably have a greater impact on the severity and location of the sustained injuries than the type of front on the striking vehicle. However, even research based on much more detailed data has not convincingly shown that the dimensional characteristics of the vehicle such as the height of the bumper influence the location of injuries (Otte et al. 2007).

In addition, some of the categories are only present in a very small number, for example cars with short bonnets whose design should reduce the occurrence or severity of some injuries. Readers should note that we also tried to characterize vehicles in another way, namely by taking separate account of the principal dimensions of their front such as the height of the radiator grille or the distance between the foremost point on the vehicle and the base of the windscreen, but none of the dimensions in question favoured any injury location.

In fact, differences in the severity of pedestrian injuries can be observed in national accident data with more “generic” vehicle categories and using fatality rates which are the only available severity criterion. Lethality is extremely high when the striking vehicle is a truck (a fatality rate of almost 25%) and it is also higher for commercial vehicles than for light vehicles. This last difference is consistent with the excess severity we have observed for MPVs. Another interesting finding from the same data is that the lethality is higher when the front left or front right of the vehicle strikes the pedestrian than when the impact is central. This may be due to the fact that the sides of the bonnet are more rigid, or because the pedestrian often ‘falls off’ the side of the bonnet and hits the ground violently.

CONCLUSION

The regulatory tests for pedestrian injuries relate to the head, pelvis and lower limb. Head injuries account for the majority of fatal injuries and a large proportion of severe injuries. All age groups are affected, and males slightly more than females, probably because of the circumstances of the accident. Females are much more susceptible to pelvic injuries, which may be extremely incapacitating, perhaps as a result of differences in morphology and fracture resistance. Injuries to the lower extremities, which are usually the location of the pedestrian’s first impact (Fildes et al. 2004; Hannon, Hadjizacharia, Chan et al. 2009), are mostly to the leg and the knee, which are the zones the most at risk of receiving a direct impact from the vehicle.

Thus, with regard to injury frequencies, the regulatory tests appear to be appropriate. In connection with severe injuries, as Fildes has already concluded (Fildes et al. 2004), it is unfortunate that the thorax is not covered by any test as, after the head, this is the body region which sustains the most severe or fatal injuries.

Acknowledgments

This work has been done in the framework of the ASP project, managed by two IFSTTAR researchers, Pierre-Jean Arnoux and Catherine Masson, and partially financed by “la Fondation pour la Sécurité Routière”.

REFERENCES

- AAAM (Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine) Abbreviated Injury Scale, 1990 Revision. Des Plaines; Illinois, USA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Amoros E, Martin JL, Lafont S, Laumon B. Actual incidences of road casualties, and their injury severity, modelled from police and hospital data, France. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18(4):360–365. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckn018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoros E, Martin JL, Laumon B. Under-reporting of road crash casualties in France. Accid Anal Prev. 2006;38(4):627–635. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assailly JP. Characterization and prevention of child pedestrian accidents : An overview : Focus : Children's road safety. J Appl Dev Psychol. 1997;18(2):257–262. [Google Scholar]

- Demetriades D, Murray J, Martin M, Velmahos G, Salim A, Alo K, Rhee P. Pedestrians injured by automobiles: relationship of age to injury type and severity. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(3):382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EEVC 2002. www.eevc.org, Improved test method to evaluate pedestrian protection afforded by passenger cars,

- Fildes B, Gabler HC, Otte D, Linder A, Sparke L. Pedestrian impact priorities using real-word crash data and harm. 2004. In: IRCOBI, Graz (Australia),

- Fontaine H, Gourlet Y. Fatal pedestrian accidents in France: a typological analysis. Accid Anal Prev. 1997;29(3):303–312. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(96)00084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson R, Rosen E, Kullgren A. Priorities of pedestrian protection--A real-life study of severe injuries and car sources. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2010;42(6):1672–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon M, Hadjizacharia P, Chan L, Plurad D, Demetriades D. Prognostic significance of lower extremity long bone fractures after automobile versus pedestrian injuries. J Trauma. 2009;67(6):1384–1388. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31819ea3e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmer T, Samaha RR, Scullion P, Ebner A, Kates R. Kinematical, physiological, and vehicle r elated influences on pedestrian injury in frontal vehicle crashes: Multivariate analysis and cross-validation. 2010. In: Ircobi Proceedings, Hanover,

- Henary B, Crandall J, Bhalla K, Mock C, Roudsari B. Child and adult pedestrian impact: the influence of vehicle type on injury severity. 47th annual proceedings of the Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine; 2003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henary BY, Ivarsson J, Crandall JR. The influence of age on the morbidity and mortality of pedestrian victims. Traffic Inj Prev. 2006;7(2):182–190. doi: 10.1080/15389580500516414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramlich T, Langwieder K, Lang D, Hell W. IRCOBI; Munich, Germany: 2002. Accident characteristics in car-to-pedestrian impact. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam D, Harland D. Road Safety in Europe; Berlin, Germany: 1992. Child pedestrian safety in the UK; pp. 183–199. [Google Scholar]

- Martin J-L, Lenguerrand E. A population based estimation of the driver protection provided by passenger cars: France 1996–2005. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2008;40:1811–1821. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui Y. Effects of vehicle bumper height and impact velocity on type of lower extremity injury in vehicle-pedestrian accidents. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2005;37(4):633–640. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno Y, Ishikawa H. “Summary of IHRA Pedestrian Safety Working Group activities proposed test methods to evaluate pedestrian protection afforded by passenger cars,”. 17th ESV (Int. Tech. Conf. on the Enhanced Safety of Vehicles).2001. [Google Scholar]

- Naci H, Chilsholm D, Baker TD. Distribution of road traffic deaths by road user group: a global comparison. Inj Prev. 2009;15:55–59. doi: 10.1136/ip.2008.018721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OCDE “La sécurité des personnes âgées dans la circulation routière,”. OCDE with OMS cooperation 1985 [Google Scholar]

- Otte D, Haasper C. Characteristics on fractures of tibia and fibula in car impacts to pedestrians and bicyclists - influences of car bumper height and shape. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med; Melbourne, Australia. 2007. pp. 63–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng RY, Bongard FS. Pedestrian versus motor vehicel accidents: an analysis of 5,000 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189(4):343–348. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roudsari BS, Mock CN, Kaufman R. An evaluation of the association between vehicle type and the source and severity of pedestrian injuries. Traffic Inj Prev. 2005;6(2):185–192. doi: 10.1080/15389580590931680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS “92, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA..” 2008.

- Schmucker U, Beirau M, Frank M, Stengel D, Matthes G, Ekkernkamp A, Seifert J. Real-world car-to-pedestrian-crash data from an urban centre. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2010;4(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1752-2897-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooij L, Bhalla K, Meissner M, Ivarsson J, Crandall J, Longhitano D, Takahashi Y, Dokko Y, Kikuchi Y. “Pedestrian crash reconstruction using multibody modeling with geometrically detailed, validated vehicle models and advanced pedestrian injury criteria,”. 2003. p. 19.

- WHO 2009. Global status report on road safety, time for action. WHO library cataloguing-in-Publication data.

- Zhang G, Cao L, Hu J, Yang KH. A field data analysis of risk factors affecting the injury risks in vehicle-to-pedestrian crashes. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med; San Diego, USA. 2008. pp. 199–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]