Abstract

In Drosophila, a phospholipase C (PLC)-mediated signaling cascade, couples photo-excitation of rhodopsin to the opening of the transient receptor potential (TRP) and TRP-like (TRPL) channels. A lipid product of PLC, diacylglycerol (DAG), and its metabolites, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) may function as second messengers of channel activation. However, how can one separate between the increase in putative second messengers, change in pH, and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2) depletion when exploring the TRPL gating mechanism? To answer this question we co-expressed the TRPL channels together with the muscarinic (M1) receptor, enabling the openings of TRPL channels via G-protein activation of PLC. To dissect PLC activation of TRPL into its molecular components, we used a powerful method that reduced plasma membrane-associated PI(4,5)P2 in HEK cells within seconds without activating PLC. Upon the addition of a dimerizing drug, PI(4,5)P2 was selectively hydrolyzed in the cell membrane without producing DAG, inositol trisphosphate, or calcium signals. We show that PI(4,5)P2 is not an inhibitor of TRPL channel activation. PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis combined with either acidification or application of DAG analogs failed to activate the channels, whereas PUFA did activate the channels. Moreover, a reduction in PI(4,5)P2 levels or inhibition of DAG lipase during PLC activity suppressed the PLC-activated TRPL current. This suggests that PI(4,5)P2 is a crucial substrate for PLC-mediated activation of the channels, whereas PUFA may function as the channel activator. Together, this study defines a narrow range of possible mechanisms for TRPL gating.

Keywords: Drosophila, Electrophysiology, Fatty Acid, Phosphatidylinositol Signaling, Phospholipase C, Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids, Diacylglycerol, TRP Channels, Phototransduction, Second Messenger

Introduction

The Drosophila transient receptor potential (TRP)2-like (TRPL) channel is a 1124-amino acid-long membrane protein. It was discovered independently from the TRP channel in a screen for calmodulin-binding proteins (1). This protein is expressed predominantly in photoreceptor cells and is one of the two founding members of the TRP channel super family (for review, see Ref. 2). TRP channels detect changes in the environment in response to a myriad of stimuli, including light (3–6).

Drosophila visual transduction is a phosphoinositide-signaling cascade mediated by Gq and phospholipase C (PLC) (7). The activation of PLC by the Gq protein promotes the opening of the light activated channels, TRP and TRPL, which depolarize the cell (Refs. 8 and 9; see also supplemental Fig. S1).

The TRPL channel shows different activation states in different expression systems. Expression of TRPL channels in Sf9 (10, 11), S2 (12, 13), and COS (14) cells results in constitutively active channels. On the other hand, the expression of the channels in HEK cells results in channels that are in their closed state (14, 15), much like the situation in photoreceptor cells, in the dark (8). It is still unclear what leads to this spontaneous activity of the TRPL channel in these expression systems. This is a point that might be important for understanding channel activation.

Activation of PLC is crucial for the opening of the TRP and TRPL channels under physiological conditions (7, 16, 17) (see also supplemental Fig. S1). Several studies have reproduced this result in heterologous expression systems (10, 14, 18). Because PLC activation results in both reduction of PI(4,5)P2 levels and the production of DAG and inositol trisphosphate (IP3), it is not yet clear which of these events is key to TRPL channel gating. The gating can be explained by several possible mechanisms: 1) a reduction of PI(4,5)P2 level in a process of disinhibition with or without the synergistic effect of second messenger production (i.e. IP3 or DAG); 2) an action of a PLC-hydrolyzing product as a second messenger (i.e. IP3 or DAG); 3) an action of a DAG hydrolyzing product as a second messenger (i.e. PUFA (12); 4) a reduction of PI(4,5)P2 levels combined with a pH diminution (19); 5) a change in lipid packing at the plasma membrane (PM) due to conversion of PI(4,5)P2, with a large hydrophilic head group, into DAG, with a small hydrophilic head group (18, 20).

The possible gating mechanisms that involve PI(4,5)P2 have been extensively investigated both in the native and heterologous expression systems. An early study performed in Drosophila photoreceptors has shown that PI(4,5)P2 serves as a substrate for the activation process (21). Two studies have suggested that PI(4,5)P2 functions as an inhibitor of the TRPL channel in heterologous expression systems. These studies showed that PI(4,5)P2 sequestration by exogenous polylysine or PI(4,5)P2 addition enhanced or suppressed the activity of constitutively active TRPL channels, respectively (10, 18). These results contradict recent data showing that PI(4,5)P2 addition to excised patches of S2 cells expressing TRPL facilitated channel activity. This same study further showed that PI(4,5)P2 reduction together with intracellular acidification led to robust opening of the channels in the native system (19). Collectively, these results indicate a crucial role for PI(4,5)P2 in TRPL gating, although the underlying mechanism is not clear (i.e. activation or inhibition).

Previous studies have indicated that IP3 or the IP3 receptor and thus Ca2+ mobilization are not involved in the gating mechanism of TRPL (22–24). This conclusion was supported by intracellular photo-release of caged Ca2+ (25). Manipulation of cellular Ca2+ in S2 cells expressing TRPL showed that Ca2+ inhibits rather than activates TRPL by a divalent open channel block mechanism (13).

Several studies have shown that DAG analogues can activate the TRPL channel (10, 18, 26). Others have shown that DAG derivatives (i.e. PUFA) open (in photoreceptor cells) or enhance activity of constitutively active TRPL channels (in expression systems) (12, 18). It is still unclear what exact role these agents have in the gating mechanism of the TRPL channel. Furthermore, some of the proposed gating mechanisms highlight different downstream effects of PLC activation. However, the physiological relevance of these results remains elusive. Because TRPL shares many common features with other members of the TRP channel superfamily, advancing the understanding of TRPL gating has an important impact on understanding the gating mechanism and functional properties of other TRP channels as well.

In this study we explored the gating mechanism of the TRPL channel using a recently established technique that has not been previously used to investigate this specific issue. To this end we set up a TRPL expression system in which we could readily induce channel opening via PLC activation together with accurate monitoring of its hydrolyzing activity. PLC hydrolyzing activity was monitored via the reduction of PI(4,5)P2 and the resulting increase in DAG levels using translocation of GFP-tagged pleckstrin homology (PH) domain (see “Experimental Procedures”). Furthermore, we used enzymatic and pharmacological tools that enabled changing the content of specific phospholipids with or without PLC activation in a spatial and temporal-controlled manner. These powerful techniques enabled dissecting the process resulting from PLC activation into its separate components without PLC activation. Using these techniques, we reconstituted a TRPL activation system in mammalian HEK cells whereby activation of PLC by co-expressed Muscarinic 1 (M1) receptor led to the opening of the TRPL channel. We showed that PI(4,5)P2 is not an inhibitor of channel activation regardless of whether its hydrolysis was combined with the addition of DAG analogues or whether PI(4,5)P2 reduction was induced under extra or intracellular acidic conditions. In addition, we demonstrated that PI(4,5)P2 is a crucial substrate for PLC-induced activation of the TRPL channel and showed that DAG analogues do not activate the channel directly, whereas linoleic acid (LA, a specific PUFA), a derivative of DAG, does.

Together, the data define a narrow range of possible mechanisms for TRPL gating. The results exclude several proposed gating mechanisms and reinforce others, especially those involving PI(4,5)P2.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression Constructs

The Drosophila TRPL construct used for experiments in HEK cells was kindly provided by Neil S. Millar (Dept. of Neuroscience, Physiology and Pharmacology, University College, London). The prmha3-TRPL plasmid provided was utilized for subcloning into Clontech C1 mammalian expression vector and used thereafter for all experiments. The mouse muscarinic receptor fused to cyan fluorescent protein at its C terminus was the kind gift of Neil M. Nathanson (Dept. of Pharmacology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA). The green fluorescent protein (GFP) pleckstrin homology fusion protein expression vector and TRPM8 mammalian expression vector were kindly provided by Sharona E. Gordon (Dept. of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington). All vectors used in the rapamycin system (Lyn11-FRB and cyan fluorescent protein-FKBP (FK506-binding protein)-Inp54p) were kindly provided by Tobias Meyer (Dept. of Molecular Pharmacology, Stanford University).

Cell Culture

HEK cells were grown at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% pen-strep (Biological Industries). Transfections were performed with the TransIt (Mirus) transfections reagent, with equal amounts of cDNA, according to the manufacturer's instructions and protocol.

Electrophysiology

HEK cells were seeded on polylysine coated coverslips at a confluence of 25%. 24–48 h before the experiment, cells were transfected to induce expression of the appropriate proteins. Single channel and whole-cell currents were recorded at room temperature using borosilicate patch pipettes of 3–5 megaohms and an Axopatch 200B (Molecular Devices) voltage-clamp amplifier. Voltage-clamp pulses were generated, and data were captured using a Digidata 1440A interfaced to a computer running the pClamp 10 software (Molecular Devices). Currents were filtered using 8-pole low pass Bessel filter at 5 kHz and sampled at 50 kHz. Series resistance compensation was performed <80% for currents above 1000 pA.

Solutions

The extracellular Tyrode solution was prepared as a Ca2+ nominal-based solution to which either 0.5 mm EGTA or 1.5 mm CaCl2 were added. In several experiments GdCl3 was added to nominal-based extracellular solution. The extracellular solution contained 145 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 15 mm HEPES, 10 mm glucose and titrated to pH 7.4. The intracellular pipette solution contained 130 mm CsCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm EGTA, 10 mm HEPES, 2 mm Na2ATP, 4.1 mm CaCl2 and titrated to pH 7.2. The experiments performed in Fig. 5 used extracellular acidic solution as indicated whereby the acidic pH was buffered using MES instead of HEPES, and all other ingredients were as mentioned above.

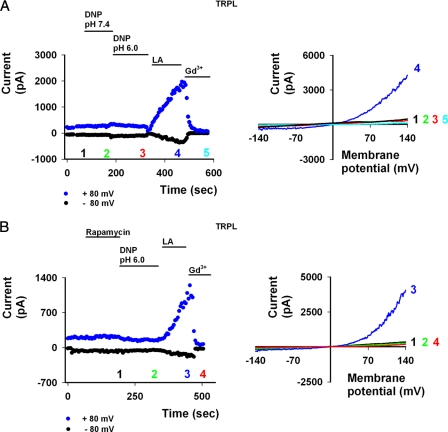

FIGURE 5.

PI(4,5)P2 depletion and further acidification do not activate TRPL in HEK cells. A, left, current values of TRPL as a function of time at +80 mV and −80 with DNP, extracellular acidic solution, and LA applications are shown. Numbers correspond to the curves presented to the right. A, right, representative I-V curves of TRPL activity in HEK cells in the presence of acidic (pH 6.0) extracellular solution are shown. No channel activity was observed in both pH 7.4 (green) and pH 6.0 (red) in the presence of DNP. Application of 60 μm LA opened the channel (blue), which was blocked by 1 mm Gd3+ (cyan). Note how acidic extracellular solution in itself has no effect on TRPL or endogenous currents in HEK cells. B, left, the current values of TRPL as a function of time at +80 and −80 mV with rapamycin, acidic solution, and LA applications is shown. Numbers correspond to the curves presented at the right. B, right, shown are representative I-V curves of TRPL activity in HEK cells after induced irreversible phosphatase activity by 500 nm rapamycin (black) and in addition to acidic (pH 6.0) extracellular solution with DNP (green). Note the absence of any effect on the closed channel. Application of 60 μm LA opened the channel (blue), which was blocked by 1 mm Gd3+ (red).

All cells were perfused via BPS-4 valve control system (Scientific Instruments) at a rate of ∼30 chamber volumes/min. Menthol and capsaicin were purchased from Sigma. 1,2-Oleoylacetylglycerol (OAG), 1-stearoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycerol (SAG), rapamycin, LA, and carbachol (CCH) were purchased from Calbiochem.

Confocal Imaging

Images of HEK cells expressing fluorescent proteins were acquired in a confocal microscope (Olympus Fluoview 300 IX70) using an Olympus UplanF1 60×/0.9 water objective. The cells were excited with an argon/krypton laser at 488 nm.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed and plotted using pClamp 10 (Molecular Devices) and Sigma Plot 8.02 (Systat software) software. Confocal images were imported as tiff single images into Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc.), where they were subsequently cropped and resized.

PI(4,5)P2 Quantification

The K-4500 competitive ELISA kit (Echelon) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. Absolute PI(4,5)P2 concentrations were calculated using the standard curve for which the change in PI(4,5)P2 levels was displayed.

Statistical Analysis

Student's paired t test was used for statistical analysis. All error bars are S.E.

RESULTS

Opening of TRPL Channel by Activation of PLC

The HEK expression system was used to study TRPL gating because the channels are in their closed state and can be opened upon application of external signals. This property is reminiscence of TRPL channels in photoreceptor cells, which are closed in the dark (15, 27, 28). The closed state of the channels made it possible to recapitulate the enzymatic cascade leading to Drosophila TRPL channel activation in a similar manner to the native system. HEK cells have been shown to allow for robust activation of mammalian TRP channels downstream of expressed M1 receptor, which utilizes endogenous Gq and PLC (29). An additional advantage of this system is the negligible endogenous currents (15, 28). Importantly, using this system allowed careful monitoring of the relative amount and dynamic changes in phospholipid content. This was performed in an array of pharmacological and enzymatic assays designed to dissect the PLC-TRPL cascade into incremental steps. Fig. 1 shows that application of CCH (the M1 agonist) resulted in activation of the TRPL channel via endogenous Gq-activated PLC in a relatively fast and robust manner. PLC activity was monitored using translocation of a GFP-tagged PH domain (30, 31). This technique is based on the specific binding of the GFP-PH probe to PI(4,5)P2 at the plasma membrane. Hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2 resulted in the translocation of the GFP-PH probe to the cytosol. Fig. 1, A and B, shows the reversible enhanced translocation of GFP-PH to the cytosol in the presence of physiological Ca2+ concentrations upon CCH application. This demonstrates that the expressed M1 can activate endogenous PLC in the HEK cell expression system. Importantly, we showed that co-expression of M1 and TRPL resulted in TRPL channel opening from a closed state upon CCH application (Fig. 1C, n = 9). The channel could be further blocked by application of Gd3+ (Fig. 1C, right I-V curve in red). The activity of the TRPL channel observed, in terms of waveform and reversal potential, is comparable with that seen for the channel in the native photoreceptor cells (18) as well as other expression systems (14). This is the first demonstration of a mammalian expression system that reconstitutes the phosphoinositide cascade which activates TRPL via a G-protein-coupled receptor, a Gq protein, and PLC.

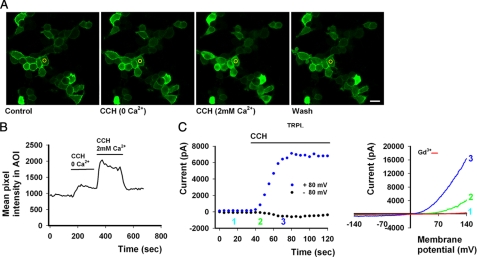

FIGURE 1.

M1-stimulated PLC activation of TRPL in HEK cells. A, shown is a representative series of confocal images of HEK cells co-expressing enhanced GFP-tagged PH domain, TRPL channels, and M1. Application of CCH to the bathing solution in a concentration that activated the TRPL channels (C, 100 μm CCH), induced movement of the enhanced GFP-tagged PH domain to the cell body (CCH) in a calcium-dependent manner, indicating the activation of PLC and hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2. A subsequent wash of CCH from the bathing solution resulted in reversible marking of the plasma membrane with enhanced GFP-tagged PH domain (scale 20 μm). B, the time course of the fluorescence changes measured in the cytosol AOI is presented (as marked in yellow). C, left, TRPL current at +80 and −80 mV as a function of time, extracted from continuous I-V curves, produced every 5 s along experiment is shown. This presentation appears for all figures. Numbers correspond to the selected I-V curves shown to the right, and their location on the time scale depict at which time point along experiment the I-V curves were produced. C, right, selected I-V curves before CCH (cyan), after CCH (green, blue), and after the addition of extracellular solution with 1 mm Gd3+ (red) are shown. Their numbers correspond to the numbers at the left and show when they were produced along the time line of the experiment.

LA Activates Drosophila TRPL

To further substantiate the competence of the HEK cell expression system to recapitulate results obtained for TRPL in other expression systems, including the native system, we explored the effect of PUFA on the channel. Several reports have implicated PUFA as a possible activator of the channel both in the native system (12, 18) and in several expression systems (10, 18). Fig. 2 demonstrates that LA (i.e. a PUFA) activated the TRPL channel both in the whole cell configuration (Fig. 2A, n = 10) and in the cell-attached mode (Fig. 2, C and D, n = 6), showing single channel activity. In both configurations, a Ca2+ open channel block results in outward rectification. However, a significant inward current can be observed at physiologically relevant potentials when LA is applied (Fig. 2B, see also Figs. 4C and 5, A and B) as observed also by others (12, 18). These results demonstrate that the HEK expression system effectively reproduces PUFA-based activation of the TRPL channel.

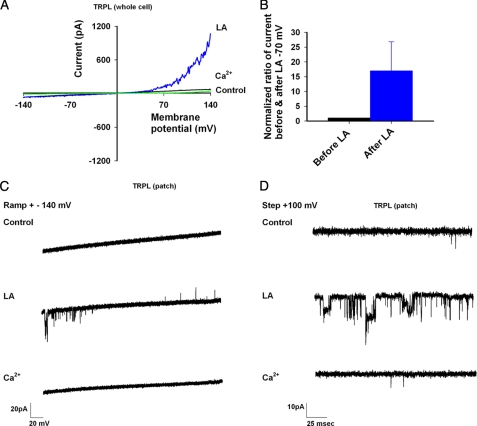

FIGURE 2.

LA activation of the TRPL channels in HEK cells. A, shown are representative I-V curves of TRPL activity in the whole cell mode as expressed in HEK cells. Note the absence of activity before LA application (black) versus robust activation after LA (blue), which is then blocked by calcium (green). B, shown is a histogram displaying normalized ratio of change in current at −70 mV with application of LA (the ratio change before LA is 1). Notice the >10-fold change in current with LA application at physiologically relevant membrane potentials. C, voltage ramps in the cell-attached mode show the level of activity of TRPL in HEK cells before and after LA and after application of Ca2+-containing solution, which blocks channel activity. D, shown is the same experiment and mode as in C, displaying the single channel activity at a voltage step of +100 mV before (control) and after LA application and after application of Ca2+ containing solution, which blocks channel activity.

FIGURE 4.

PI(4,5)P2 depletion and its effect on TRPL and TRPM8 channel activity. A, the graph shows mean pixel intensity of cells exhibiting GFP-PH translocation by Inp54p phosphatase-induced PI(4,5)P2 depletion as a function of time from the PM to the cytosol in an irreversible manner. Confocal images of the experiment at different stages are depicted by the numbering (area of interest marked by yellow circle, scale 10 μm). B, shown are line profile graphs before (black) and after rapamycin application (red) and the corresponding images shown below (scale 10 μm). C, left, shown are current values of TRPL as a function of time at +80 and −80 mV with rapamycin and LA applications. Numbers correspond to the curves presented to the right and depict the time points of each I-V curve along the time axis of the experiment. C, right, shown are representative I-V curves of TRPL activity before (black) and after induced phosphatase activity (blue) in HEK cells and after the application of LA 60 μm (red). Further addition of Gd3+ blocks channel activity (green). D, left, current values of TRPM8 as a function of time at +80 and −80 mV with menthol and rapamycin applications. Numbers correspond to the curves presented to the right. D, right, shown are representative I-V curves of TRPM8 activity before (red) and after menthol-induced activity (pink) and after induced phosphatase activity (blue) in HEK cells in the presence of 200 μm menthol. E, left, shown are current values of TRPM8 as a function of time at +80 and −80 mV with menthol and CCH applications. Numbers correspond to the curves presented to the right. E, right, shown are representative I-V curves of TRPM8 activity before (black) and after menthol-induced activity (blue) and after M1-induced PLC activation (green) in HEK cells in the presence of 200 μm menthol.

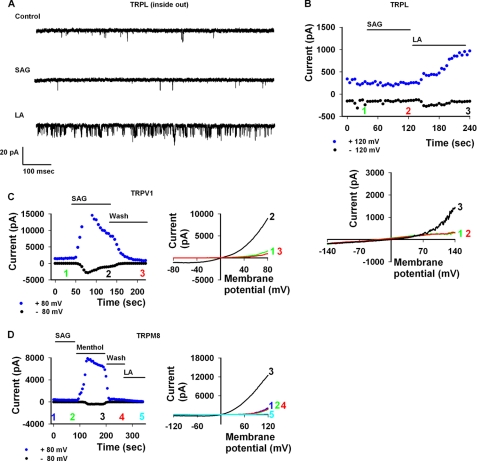

A DAG Analog Does Not Activate TRPL Channel Directly

There is a consensus that IP3 (a product of PLC activity) has a negligible if any effect on TRPL and TRP activation in the native Drosophila photoreceptors as well as in the Drosophila S2 cell expression system (22–24). In contrast, the role of DAG (the other product of PLC hydrolysis) in TRPL gating is still not clear (10, 12, 18, 26, 32). Our results (see Fig. 6, see below) showed that direct application of OAG, a DAG analog, did not lead to channel opening (Fig. 6A). This result is consistent with studies in the native photoreceptor cell (3), but not with other reports, for reasons which we do not fully comprehend. To further investigate this issue, we applied SAG, a more typical DAG analog. Application of SAG to either inside-out patches or in the whole cell configuration did not lead to opening of the TRPL channel. As a positive control we used LA, which readily activated the TRPL channel (Fig. 3, A and B, n = 4). To demonstrate that SAG application was effective, we applied SAG to expressed and constitutively open TRPV1 channels. We observed a robust and reversible facilitation under the same conditions (Fig. 3C, n = 4) as previously reported (33). Based on these results and on results obtained for TRPL in S2 (18) and in the Sf9 cell expression systems (10), we explored the possibility that the SAG effect on the TRPV1 channel represents enhanced activity of various TRP channels, which are already in their open state. To this end, we applied SAG to constitutively open TRPM8 channels, expressed in HEK cells, and found no effect (Fig. 3D, n = 4). However, menthol did facilitate further channel opening in a robust and reversible manner, as previously described (34). LA further inhibited channel activity, as previously reported (35). These results suggest that the SAG effect is channel-specific and that DAG does not gate the TRPL channel directly.

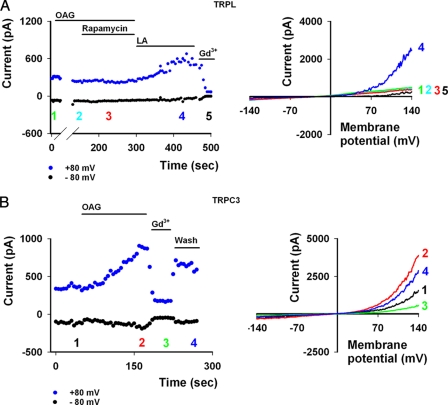

FIGURE 6.

OAG application and PI(4,5)P2 depletion do not activate TRPL channels in HEK cells. A, left, current values of TRPL as a function of time at +80 and −80 mV with OAG, rapamycin, and LA applications are shown. Numbers correspond to the I-V curves to the right. A, right, selected I-V curves of TRPL activity in HEK cells show only a marginal leak (green). Application of 100 μm OAG (cyan) and 500 nm rapamycin (red) has no effect. Application of 60 μm LA (blue) opens the channel, which can be further blocked by application of 1 mm Gd3+ (black). B, left, current values of TRPC3 as a function of time at +80 and −80 mV with OAG application are shown. Numbers correspond to the curves presented to the right. B, right, shown are representative I-V curves of TRPC3 activity before (black) and after OAG application (red). Subsequent addition of 1 mm Gd3+ blocked the channel (green) in a reversible manner (blue).

FIGURE 3.

A DAG analog does not activate TRPL in HEK cells. A, shown are representative traces of single channel activity of TRPL at a holding potential of +100 mV in the inside-out configuration. Notice negligible activity in control as well as with the application of SAG 10 μm as compared with TRPL activity after LA application. B, top, shown are current values of TRPL channel activity as a function of time at +120 and −120 mV extracted from continuous I-V curves produced along the experiment with application of SAG and LA. Numbers correspond to the selected I-V curves shown at the bottom, and their location on the time scale depict at which time point along experiment the I-V curves were produced. B, bottom, representative I-V curves of TRPL activity in HEK cells in the presence of SAG 10 μm (red) are shown. Application of LA 60 μm opened the channel (black). Note the absence of effect when applying SAG to the bathing solution (red trace). The numbers to the right of each curve correspond to the numbers at the top and show when they were produced along the time line of the experiment. C, left, shown are the current values of TRPV1 as a function of time at +80 and −80 mV with SAG application. Numbers correspond to the curves presented at the right. C, right, representative I-V curves of TRPV1 activity in HEK cells before (green) and after application of 10 μm SAG (black) and after wash (red) are shown. D, left, shown are the current values of TRPM8 as a function of time at +80 and −80 mV with SAG, menthol, and LA applications. Numbers correspond to the curves presented to the right. D, right, shown are representative I-V curves of TRPM8 activity in HEK cells before (blue) and after application of 10 μm SAG (green). Note that there is no effect. Application of 200 μm menthol increased the current (black) in a reversible manner (red). Subsequent addition of 60 μm LA decreased the current to near zero values (cyan).

PI(4,5)P2 Does Not Function as Inhibitor of TRPL Channel Activation

Several studies have shown that PI(4,5)P2 has a crucial role in TRPL channel activation, as expected from it being the substrate of PLC enzymatic activity. However, these studies have been a subject of controversy over the years due to the inconsistent observations pertaining to the PI(4,5)P2 modulatory role in this process, as mentioned above. To resolve this issue, we adapted the Inp54p phosphatase rapamycin system (Ref. 31; see supplemental Fig. S2) to explore whether PI(4,5)P2 plays an inhibitory role on Drosophila TRPL channel gating. In this paradigm, PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis is attained by translocation of expressed Inp54p yeast PI(4,5)P2-specific phosphatase to the plasma membrane upon the addition of rapamycin. Rapamycin acts as a heterodimerization agent that dimerizes the FKBP (FK506-binding protein) part of FK506, conjugated to the Inp54p phosphatase, to a membrane anchor possessing the FRB part of mTOR. Inp54p phosphatase specifically converts PI(4,5)P2 into PI(4)P at the plasma membrane (31). To monitor the specific hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2 at the plasma membrane, we utilized the translocation of the GFP-PH probe from the plasma membrane to the cytosol upon decrease of PI(4,5)P2 levels at the PM. The addition of rapamycin led to a reduction of PI(4,5)P2 levels in an irreversible manner at the PM, as monitored by the translocation of GFP-PH from the plasma membrane to the cytosol (Fig. 4, A and B). Importantly, application of rapamycin to cells, which co-expressed the Inp54p system, GFP-PH, and TRPL did not lead to opening of the TRPL channel despite PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis at the PM (Fig. 4C). As a positive control, we co-applied LA to cells, which underwent rapamycin-induced activation of Inp54p (and, therefore, PI(4,5)P2 depletion) and observed channel activation (Fig. 4C, n = 5). Moreover, there was no observable difference in TRPL current amplitude after LA addition in the presence or absence of PI(4,5)P2 depletion (data not shown). This suggests that PI(4,5)P2 does not play a positive modulatory role with respect to TRPL, as is true for TRPM8 (36), in which it was shown to be critical for menthol-induced activation (37). In contrast to the null effect on TRPL, PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis by the Inp54p phosphatase dramatically reduced menthol-activated TRPM8 channel activity (Fig. 4D) as previously shown (36). This indicates that PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis by the Inp54p-rapamycin system can affect other TRP channels (Ref. 36 and Fig. 4D) and that the system we have set up is robust and can be tuned to manipulate PI(4,5)P2 levels in a spatial and timely manner. To further characterize the effect of the Inp54p-rapamycin system on TRPM8, we performed similar experiments in which we achieved PI(4,5)P2 depletion by M1-induced PLC activation in the presence of menthol. We observed a similar effect on current amplitude (Fig. 4E, n = 4). Fig. 4, thus, shows directly for the first time that PI(4,5)P2 does not act as an inhibitor of the TRPL channel.

PI(4,5)P2 Hydrolysis Combined with Cellular Acidification Does Not Activate TRPL Channels

A new model has been put forward recently suggesting that a reduction of PI(4,5)P2 together with intracellular acidification leads to opening of the Drosophila light-activated channels. It is established that PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis and production of protons (H+) are both the consequence of PLC enzymatic activity (19). We, therefore, expected that intracellular acidification together with selective PI(4,5)P2 reduction should lead to opening of the TRPL channel. Our experimental system described above has the advantage of directly testing the reduction of PI(4,5)P2 without activation of PLC, whereas previous studies depleted PI(4,5)P2 by PLC activation. PI(4,5)P2 depletion by way of PLC activation could lead to accumulation of DAG and its metabolites, to Ca2+ mobilization, and to phosphorylation (19). Fig. 5A shows that extracellular as well as intracellular acidification, by applying a protonophore, the 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP), using an acidic extracellular solution, has no apparent effect on the activation state of TRPL. We proceeded to utilize the Inp54p phosphatase-rapamycin system to selectively hydrolyze PI(4,5)P2 at the PM in an irreversible manner together with intracellular acidification in TRPL-expressing HEK cells. Fig. 5B shows that reduction of PI(4,5)P2 together with intracellular acidification does not open the TRPL channels, whereas LA readily activated the channels, serving as a positive control (Fig. 5B, n = 4). Moreover, PI(4,5)P2 depletion by the rapamycin system led to irreversible translocation of GFP-PH from the plasma membrane to the cytosol. In these experiments, washout with DNP in extracellular acidic solution had no reversible effect on the distribution of GFP-PH (data not shown). These results clearly show that PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis combined with cellular acidification does not activate the TRPL channels expressed in HEK cells.

PI(4,5)P2 Hydrolysis Combined with Application of DAG Analogues Does Not Activate TRPL Channels

To further characterize the gating mechanism of TRPL, we explored the possibility that this gating is a synergy between PI(4,5)P2 depletion and DAG production, as previously suggested for the TRP channels (38). According to this model, both events must take place to gate the channel. Fig. 6 shows that application of a DAG analog (OAG) together with a reduction in PI(4,5)P2 levels, induced by activation of the Inp54p rapamycin system, did not lead to TRPL channel opening. Subsequent application of LA did open the channels, which were blocked by the addition of Gd3+ (Fig. 6A). As an additional positive control, we showed that OAG facilitated constitutively active TRPC3 channels (Fig. 6B), as previously reported (39). These results indicate that PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis combined with exogenous application of a DAG analog does not activate the TRPL channels expressed in HEK cells.

PI(4,5)P2 Functions as Substrate for PLC Enzymatic Activity in Gating Mechanism of TRPL Channels

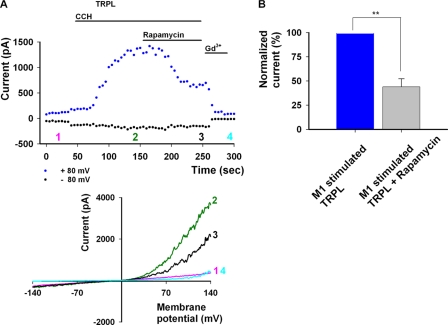

The results shown above could not demonstrate a direct modulatory role for PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis in the gating mechanism of TRPL. This is in spite of reports demonstrating a direct role for PI(4,5)P2 in the gating mechanism of TRP channels from the TRPM and TRPV subfamilies that was reproduced in the present study. Nonetheless, PLC-dependent hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2 activated the TRPL channel (Fig. 1C). Based on the results of Zuker and co-workers (21), we tested whether PI(4,5)P2 functions solely as a substrate for PLC enzymatic activity in the opening of the TRPL channel. Zuker and co-workers (21) showed that in the cds1 mutant fly (which lacks the CDP-diacylglycerol synthase (CDS)-converting phosphatidic acid into phosphatidylinositol), there is a reduction in the amplitude of the light-induced current compared with WT flies. Furthermore, recovery of light responsiveness fails in cds1 mutant flies after light-induced PI(4,5)P2 depletion, whereas exogenous application of PI(4,5)P2 (under the same conditions) restores the light-induced current (21). These results indicate that the role of PI(4,5)P2 is to serve as a substrate for light-induced PLC activity. We, therefore, tested whether activation of the TRPL channel by PLC stimulation in conjunction with reduction of PI(4,5)P2 in a timely controlled manner would reduce the TRPL current. Fig. 7 shows rapamycin-induced attenuation of TRPL-dependent current induced by activation of M1 and PLC (Fig. 7, A and B, n = 4). Sustained stimulation of the M1 receptor resulted in sustained TRPL activation and, therefore, the reduction in TRPL current is the result of rapamycin-induced reduction in PI(4,5)P2 concentrations (see Fig. 1C). We also excluded the possibility that under these specific conditions PI(4,5)P2 had a positive modulatory role on the TRPL channel, as shown for TRPV1 (40) and TRPM8 (36). This is because the channel could be readily opened in a robust manner by LA after significant reduction in PI(4,5)P2 levels (see Fig. 4C). From the above experiments we conclude that PI(4,5)P2 serves as a substrate for PLC enzymatic activity, which is required for TRPL activation under physiological conditions. The experiment of Fig. 7 thus shows that PI(4,5)P2 is necessary but not sufficient for gating the TRPL channel.

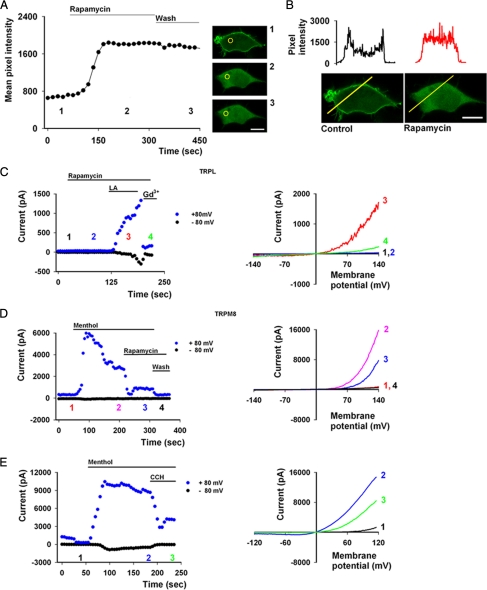

FIGURE 7.

PLC-mediated TRPL activity is attenuated in the presence of phosphatase activity, converting PI(4,5)P2 into PI(4)P. A, top, current values of TRPL as a function of time at +80 and −80 mV with CCH and rapamycin applications are shown. Numbers correspond to the curves presented at the bottom. A, bottom, shown are representative I-V curves of TRPL activity in HEK cells after induced PLC activity and additional phosphatase activity, which depletes PI(4,5)P2. In control conditions, no activity was seen for TRPL (pink). Activation of PLC via M1 by 100 μm CCH led to robust activity (dark green), which is attenuated by rapamycin 500 nm (black) and further blocked by 1 mm Gd3+ (cyan). B, shown is a histogram depicting the extent of decrease in current at +80 mV in response to rapamycin application.

PUFA Is Possible Endogenous Activator of TRPL Channels

A previous detailed study by Pak and co-workers (41) has suggested the involvement of DAG lipase in light excitation. In addition, it has been well established that exogenous application of PUFAs robustly activates Drosophila TRP and TRPL channels in the native photoreceptor cells (12, 18) as well as in several heterologous expression systems (10, 18). Moreover, it was shown that activation of the channels by PUFA is direct and does not require activation of PLC (18). Together these studies suggest that a DAG lipase enzyme, which converts DAG into PUFA, is involved in the activation of these channels under physiological conditions.

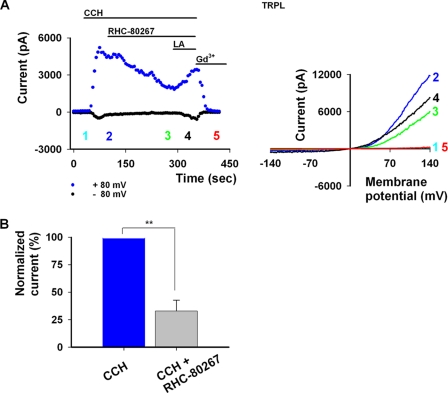

We, therefore, expected that activation of the TRPL channel via PLC stimulation combined with inhibition of DAG conversion into PUFA by a DAG lipase inhibitor would decrease the TRPL-dependent current. This is based on PUFA activation of the channels and the inhibitory effects of the DAG lipase mutants on the channels. Fig. 8 shows that this expectation was realized. A significant reduction in TRPL-dependent current was seen after application of DAG lipase inhibitor RHC-80267 in the presence of CCH-dependent PLC activation. Because sustained PLC activation resulted in sustained TRPL activity (see also Fig. 1, B and C), the observed reduction in TRPL current during application of the DAG lipase inhibitor RHC-80267 is the consequence of delimiting a TRPL activator (i.e. a decrease in PUFA). Subsequent application of LA reopened the TRPL channel, in the presence of the DAG lipase inhibitor, indicating that the production of PUFA is the limiting factor in the activation of the TRPL channels (Fig. 8, n = 4). Previous reports have shown that application of RHC-80267 resulted in increased activity of TRPC6 (39) and TRPC3 (42) channels, presumably due to DAG accumulation. For these channels, DAG has been shown to be an activator and PLC, an essential mediator. These reports indicate that RHC-80267 does not inhibit PLC activity and, therefore, does not account for the observed reduction in TRPL activity. Together our present results and other previous reports support the hypothesis that a DAG lipase product activates the TRPL channels.

FIGURE 8.

PLC-mediated TRPL activity is attenuated in the presence of DAG-lipase inhibitor RHC-80267. A, left, shown are current values of TRPL as a function of time at +80 and −80 mV with CCH, RHC-80267, and LA applications. Numbers correspond to the curves presented at the right. A, right, shown are representative I-V curves of TRPL activity in HEK cells after induced PLC activity and application of RHC-80267. In control conditions no activity was seen for TRPL (cyan). Activation of PLC via M1 by 100 μm CCH led to robust activity (blue), which was attenuated by RHC-80267 100 μm (green). Further application of LA 60 μm increased channel activity (black) and was further blocked by 1 mm Gd3+ (red). B, shown is a histogram depicting the extent of decrease in current at + 80 mV in response to RHC-80267application.

DISCUSSION

In this work TRPL gating was studied for the first time in an expression system whereby the channels are in their closed state. This simulates the native channels of the photoreceptor cells in the dark. Moreover, the TRPL channels were activated by a PLC-mediated cascade as in the native system. Therefore, the gating mechanism of TRPL could be better addressed as compared with previous studies. The drawback of most previous studies using heterologously expressed and constitutively active TRPL channels is that the gating mechanism was already in operation and the various manipulations only modulated the already active channels. This consideration may help explain the difference between the results of this work and previous studies obtained in different expression systems.

PI(4,5)P2 Does Not Act as Inhibitor, Whereas PUFA Acts as Activator of the TRPL Channel

The main results obtained in the present study are as follows. (i) The only role of PI(4,5)P2 in TRPL channel gating is to function as a substrate for PLC enzymatic activity (Fig. 7). ii) PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis per se does not activate the TRPL channels, indicating that it does not act as an inhibitor of the TRPL channel. This result was also demonstrated for PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis combined with acidification (Figs. 4 and 5). (iii) Application of DAG analogues either in isolation or in combination with PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis does not have a direct role in TRPL gating (Figs. 3 and 6). However, hydrolysis of DAG and the ensuing production of PUFA did activate the TRPL channels as shown by direct PUFA activation of the TRPL channels in both the native cells and expression systems (Ref. 12 and Figs. 2–6). (iv) Activation of the TRPL channel via PLC stimulation together with inhibition of DAG conversion into PUFA by a DAG lipase inhibitor decreases the TRPL-dependent current. This result is consistent with PUFA acting as an activator of the channels (Fig. 8).

Use of Inp54p-Rapamycin System for Depleting PI(4,5)P2

A major theme in the present study is the question of the role of PI(4,5)P2 in the activation and opening of the TRPL channels, which also serves as a model for TRP channels in general. Many groups have attempted to tackle the question of TRP channel gating and over the years have received conflicting results. In this study we chose to use the Inp54p-rapamycin system to help resolve this issue. We showed that depletion of PI(4,5)P2 using the Inp54p-rapamycin system leads to no apparent opening of the channels (Fig. 4C). Two lines of evidence support the validity of this observation. 1) We used the Inp54p-rapamycin system to show the effect for menthol-activated TRPM8 channel, which resulted in a large and robust decrease in current (Fig. 4D), as also shown by others (36). Moreover, the fact that we observed a robust decrease in TRPM8 current for both M1 stimulation and Inp54p activation (Fig. 4, D and E) indicates that the Inp54p-rapamycin system we used depletes PI(4,5)P2 robustly. Other investigators have also shown that from several phosphoinositides incorporated into planar lipid bilayers, PI(4,5)P2 is the most effective in allowing activation of TRPM8 by menthol, validating a prominent role for PI(4,5)P2 in TRPM8 activation (37). 2) We found that the sole role of PI(4,5)P2 is to serve as a substrate for PLC activation and the production of a downstream TRPL activator. In this experiment we observed that depletion of PI(4,5)P2 with the Inp54p-rapamycin system significantly reduced the M1 receptor-induced TRPL current, validating again the effectiveness of the Inp54p-rapamycin system. Together, the above observations demonstrate the efficiency of the Inp54p-rapamycin system in reducing PI(4,5)P2 levels.

The well established Inp54p-rapamycin system has been extensively used in effectively reducing PI(4,5)P2 levels when exploring a variety of ion channels that were used as PI(4,5)P2 biosensors. 1) It was first shown by the pioneering studies of Hille and co-workers (31) that the Inp54p-rapamycin system induced PI(4,5)P2 depletion in conjunction to KCNQ channel inhibition. 2) In parallel, Balla and Varnai (36) also developed the same strategy and demonstrated its power for the PI(4,5)P2-dependent TRPM8 channels. This paved the way for other groups to use and validate this system as a means to reduce PI(4,5)P2 without production of IP3, DAG, and calcium mobilization as occurs when activating PLC (40, 43–45). The above investigators only used strategies similar to ours to validate the use of the Inp54p-rapamycin system in reducing PI(4,5)P2 levels in a significant near-null manner.

In an attempt to further characterize this system, we tried to quantify directly and for the first time PI(4,5)P2 levels before and after activating the rapamycin-Inp54p system and also after M1 stimulation of PLC activation using a biochemical assay. We found that there was up to a 40% reduction in total PI(4,5)P2 levels after activation of the rapamycin-Inp54p system. A similar extent of decrease in PI(4,5)P2 levels (up to 55%) was also observed when depleting PI(4,5)P2 by M1 stimulation and PLC activation. We suggest that the biochemically monitored reduction of PI(4,5)P2 levels observed for both strategies is an underestimate of the true extent for the following reasons. The great advantage of the imaging combined with the electrophysiology experiments is the use of single living cells measuring PI(4,5)P2 levels dynamically. On the other hand, the biochemical quantification, which paralleled exactly the conditions used for imaging and electrophysiology, entailed the use of a heterogeneous population in terms of transfection efficiency and gives only an average static measurement of PI(4,5)P2 levels.

Possible Models for TRPL Gating

Over the years a large volume of data exploring TRPL-gating mechanisms has been obtained both in the native system and in several heterologous expression systems. These results have been used to formulate several possible models for TRPL gating. Among them are 1) the store-operated model in which the product of PLC enzymatic activity, IP3, mobilizes Ca2+ from the internal Ca2+ stores and opens the channel via Ca2+ store depletion (15, 46, 47). This model could not be supported experimentally (22, 24). 2) The second model is activation of the channel by the additional product of PLC enzymatic activity, DAG, or its metabolite PUFA (10, 12, 26, 48). 3) The third model is PI(4,5)P2 acting as an inhibitor of the channel whereby PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis by PLC activity would lead to relief of inhibition on the channel (10, 18, 19).

A question arises as to whether DAG is the physiological activator of the channels. In support of DAG being the native activator are the results showing that in DAG kinase mutants, in which inactivation of DAG is impaired, the channels are constitutively active (32). In addition, exogenous application of DAG analogues to excised patches from native photoreceptor cells activated the channels, although with unusually slow kinetics (26). However, exogenous application of DAG to intact photoreceptor cells in the whole cell configuration had no effect (Ref. 3 see also Figs. 3 and 6). Furthermore, DAG kinase was found to be localized outside the signaling compartment of the photoreceptor cells (49), which is inconsistent with the expected rapid inactivation of DAG, required for fast turnoff of the light response. Our results are consistent with the previously proposed idea that a DAG metabolite (i.e. PUFA) is an alternative candidate for a physiological activator of the channels. In support of this possibility, application of LA to both the native and expressed TRPL channels robustly activated the channels (Ref. 12; see also Fig. 2). Furthermore, the constitutive activity of the channels in the DAG kinase mutant (32) could arise from DAG conversion into PUFA. Indeed, recent studies have isolated a DAG lipase mutant shown to be necessary for TRP channel regulation (41). Our data showing that inhibition of DAG conversion into PUFA by a DAG lipase inhibitor results in decreased TRPL-dependent current are consistent with the results of the above mutant. However, the localization of the DAG lipase enzyme (mainly outside the signaling compartment) together with the need for an additional step in the activation cascade is not consistent with the known fast kinetics of the light response.

In general, a major difficulty in exploring the gating mechanism of TRP channels is the poly-modal nature of channel activation (4, 5). Accordingly, it is not clear if many of the possible ways to activate the channels are relevant to the physiological mechanism of activation. Even exploration of TRP and TRPL gating in the native system of the photoreceptor cells suffers from the ability to activate the channels in several manners. This is exemplified by activation of the channels by anoxia in the living intact fly (50). Therefore, detailed knowledge of the native enzymatic cascade leading to channel activation is crucial for elucidating the physiological mechanism underlying TRP and TRPL gating. In fly phototransduction, it has been well established that activation of PLC is absolutely essential for TRPL activation. Having this vital information in hand makes it possible to reconstitute in heterologous expression systems the enzymatic cascade and auxiliary molecular tools capable of dissecting the several possible pathways diverting from signal activated PLC. It is also essential that the expressed TRPL channels stay in their closed state in the absence of activating signals, as gating is defined as a transition from the closed to the open state of the channel.

The results of the present study define a narrow range of possible mechanisms for TRPL gating. Accordingly, the results are consistent with a DAG product, PUFA, acting as an activator of the channels. In such a model PUFA may gate the channels in at least two ways; either as a second messenger, which directly binds to the channel, leading to its opening, or as a specific modulator, which affects the interactions of the channel with its membrane lipid environment. To separate between these two models, PUFA binding and its binding site on the channel should be demonstrated. Alternatively, the effects of PUFA on PM lipid-channel interactions should be demonstrated.

This study makes significant progress in understanding TRPL gating not by proposing new models but by using new tools that explore modalities in a unique manner. The present study also provides important insight on PLC-mediated activation/modulation of other proteins including other TRP channels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Tobias Meyer for all vectors used for the rapamycin system, Neil S. Millar for the prmha3-TRPL plasmid, Neil M. Nathanson for the M1 muscarinic receptor plasmid, and Sharona E. Gordon for the GFP-PH and the TRPM8 plasmids. We also thank Maximilian Peters, Daniela Dadon, and David Zeevi for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 EY 03529. This work was also supported by the Israel Science Foundation, the United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation, and the German-Israel Foundation.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- TRP

- transient receptor potential

- TRPL

- TRP-like

- PI(4,5)P2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-diphosphate

- PLC

- phospholipase C

- IP3

- inositol trisphosphate

- PM

- plasma membrane

- M1

- Muscarinic 1

- LA

- linoleic acid

- OAG

- 1,2-oleoylacetylglycerol

- SAG

- 1-stearoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycerol

- CCH

- carbachol

- DNP

- 2,4-dinitrophenol

- DAG

- diacylglycerol

- PH

- pleckstrin homology.

REFERENCES

- 1. Phillips A. M., Bull A., Kelly L. E. (1992) Neuron 8, 631–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Minke B. (2010) J. Neurogenet. 24, 216–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hardie R. C. (2007) J. Physiol 578, 9–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Minke B. (2006) Cell Calcium 40, 261–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramsey I. S., Delling M., Clapham D. E. (2006) Annu. Rev. Physiol 68, 619–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Venkatachalam K., Montell C. (2007) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 387–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Devary O., Heichal O., Blumenfeld A., Cassel D., Suss E., Barash S., Rubinstein C. T., Minke B., Selinger Z. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 6939–6943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hardie R. C., Minke B. (1992) Neuron 8, 643–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Niemeyer B. A., Suzuki E., Scott K., Jalink K., Zuker C. S. (1996) Cell 85, 651–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Estacion M., Sinkins W. G., Schilling W. P. (2001) J. Physiol. 530, 1–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harteneck C., Obukhov A. G., Zobel A., Kalkbrenner F., Schultz G. (1995) FEBS Lett. 358, 297–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chyb S., Raghu P., Hardie R. C. (1999) Nature 397, 255–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Parnas M., Katz B., Minke B. (2007) J. Gen. Physiol. 129, 17–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hambrecht J., Zimmer S., Flockerzi V., Cavalié A. (2000) Pflugers Arch. 440, 418–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu X. Z., Li H. S., Guggino W. B., Montell C. (1997) Cell 89, 1155–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bloomquist B. T., Shortridge R. D., Schneuwly S., Perdew M., Montell C., Steller H., Rubin G., Pak W. L. (1988) Cell 54, 723–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Minke B., Selinger Z. (1991) Progress in Retinal Research (Osborne N. A., Chader G. J., eds) pp. 99–124, Chapter 5, Pergamon Press Ltd., Oxford, U.K [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parnas M., Katz B., Lev S., Tzarfaty V., Dadon D., Gordon-Shaag A., Metzner H., Yaka R., Minke B. (2009) J. Neurosci. 29, 2371–2383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huang J., Liu C. H., Hughes S. A., Postma M., Schwiening C. J., Hardie R. C. (2010) Curr. Biol. 20, 189–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Katz B., Minke B. (2009) Front. Cell Neurosci. 3, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu L., Niemeyer B., Colley N., Socolich M., Zuker C. S. (1995) Nature 373, 216–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Acharya J. K., Jalink K., Hardy R. W., Hartenstein V., Zuker C. S. (1997) Neuron 18, 881–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hardie R. C., Raghu P. (1998) Cell Calcium 24, 153–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Raghu P., Colley N. J., Webel R., James T., Hasan G., Danin M., Selinger Z., Hardie R. C. (2000) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 15, 429–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hardie R. C. (1995) J. Neurosci. 15, 889–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Delgado R., Bacigalupo J. (2009) J. Neurophysiol. 101, 2372–2379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hardie R. C., Mojet M. H. (1995) J. Neurophysiol. 74, 2590–2599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lev S., Minke B. (2010) Methods Enzymol. 484, 591–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Runnels L. W., Yue L., Clapham D. E. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 329–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Balla T., Varnai P. (2002) Sci. STKE 2002, l3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Suh B. C., Inoue T., Meyer T., Hille B. (2006) Science 314, 1454–1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Raghu P., Usher K., Jonas S., Chyb S., Polyanovsky A., Hardie R. C. (2000) Neuron 26, 169–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Woo D. H., Jung S. J., Zhu M. H., Park C. K., Kim Y. H., Oh S. B., Lee C. J. (2008) Mol. Pain 4, 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peier A. M., Moqrich A., Hergarden A. C., Reeve A. J., Andersson D. A., Story G. M., Earley T. J., Dragoni I., McIntyre P., Bevan S., Patapoutian A. (2002) Cell 108, 705–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Parnas M., Peters M., Minke B. (2009) Channels 3, 164–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Varnai P., Thyagarajan B., Rohacs T., Balla T. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 175, 377–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zakharian E., Cao C., Rohacs T. (2010) J. Neurosci. 30, 12526–12534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hardie R. C., Raghu P., Moore S., Juusola M., Baines R. A., Sweeney S. T. (2001) Neuron 30, 149–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hofmann T., Obukhov A. G., Schaefer M., Harteneck C., Gudermann T., Schultz G. (1999) Nature 397, 259–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lukacs V., Thyagarajan B., Varnai P., Balla A., Balla T., Rohacs T. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 7070–7080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Leung H. T., Tseng-Crank J., Kim E., Mahapatra C., Shino S., Zhou Y., An L., Doerge R. W., Pak W. L. (2008) Neuron 58, 884–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Venkatachalam K., Zheng F., Gill D. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 29031–29040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klein R. M., Ufret-Vincenty C. A., Hua L., Gordon S. E. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26208–26216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Suh B. C., Leal K., Hille B. (2010) Neuron 67, 224–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yao J., Qin F. (2009) PLoS. Biol. 7, e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hardie R. C., Minke B. (1993) Trends Neurosci. 16, 371–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vaca L., Sinkins W. G., Hu Y., Kunze D. L., Schilling W. P. (1994) Am. J. Physiol. 267, C1501–C1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hardie R. C., Martin F., Cochrane G. W., Juusola M., Georgiev P., Raghu P. (2002) Neuron 36, 689–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Masai I., Suzuki E., Yoon C. S., Kohyama A., Hotta Y. (1997) J. Neurobiol. 32, 695–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Agam K., von Campenhausen M., Levy S., Ben-Ami H. C., Cook B., Kirschfeld K., Minke B. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 5748–5755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.