Background: Hed1 attenuates the activity of Rad51 during meiotic recombination to allow Dmc1-dependent formation of interhomolog crossovers.

Results: Hed1 possesses DNA binding and self-association activities and stabilizes Rad51 presynaptic filament.

Conclusion: DNA binding, Rad51 interaction, and self-association are essential for Hed1 function as a key regulator of meiotic recombination.

Significance: Our results shed light on the mechanism of interhomolog bias in meiotic recombination.

Keywords: Chromosomes, DNA-binding Protein, DNA Damage, Homologous Recombination, Meiosis, Rad51 and Dmc1 Recombinases, Double-strand Breaks, Presynaptic Filament

Abstract

During meiosis, recombination events that occur between homologous chromosomes help prepare the chromosome pairs for proper disjunction in meiosis I. The concurrent action of the Rad51 and Dmc1 recombinases is necessary for an interhomolog bias. Notably, the activity of Rad51 is tightly controlled, so as to minimize the use of the sister chromatid as recombination partner. We demonstrated recently that Hed1, a meiosis-specific protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, restricts the access of the recombinase accessory factor Rad54 to presynaptic filaments of Rad51. We now show that Hed1 undergoes self-association in a Rad51-dependent manner and binds ssDNA. We also find a strong stabilizing effect of Hed1 on the Rad51 presynaptic filament. Biochemical and genetic analyses of mutants indicate that these Hed1 attributes are germane for its recombination regulatory and Rad51 presynaptic filament stabilization functions. Our results shed light on the mechanism of action of Hed1 in meiotic recombination control.

Introduction

During meiosis, programmed DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs)3 introduced by the Spo11-associated protein complex trigger genome-wide homologous recombination (HR) (1, 2). The repair of these meiotic DSBs is specifically geared toward the formation of crossovers between homologous chromosomes. These crossover events are crucial for the establishment of proper connections between the homologues, so as to facilitate their attachment to the spindle apparatus and their faithful disjunction in the first meiotic division (2–4). In contrast, HR repair events in vegetative cells mostly involve the sister chromatid as information donor, and the generation of crossover products is actively suppressed (5, 6).

Meiotic DSB repair is catalyzed by two highly conserved recombinases, Rad51 and Dmc1, orthologs of the bacterial RecA protein. While Dmc1 is meiosis-specific, Rad51 is also essential for mitotic DNA repair (7–9). The catalytically active form of these recombinases comprises a right-handed protein polymer on ssDNA. The recombinase-ssDNA filament, commonly referred to as the presynaptic filament, is assembled on 3′ ssDNA tails generated via the nucleolytic resection of DSB ends (5, 7, 8, 10). A class of ancillary factors called “mediators,” such as yeast Rad52 and Rad55-Rad57, and human BRCA2 facilitate presynaptic filament assembly. The efficiency of the DNA strand invasion step that leads to formation of a displacement loop (D-loop) is greatly enhanced by the DNA motor proteins Rad54 and Rdh54/Tid1 (2, 8, 9) and by the meiosis-specific Hop2-Mnd1 complex (11–13).

Genetic studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have furnished evidence for the existence of two distinct meiotic recombination pathways, with one being dependent on Rad51 alone (Rad51-only pathway) and the other on both Rad51 and Dmc1 (Dmc1-dependent pathway) (14). The coordinated action of Rad51 and Dmc1 in the Dmc1-dependent pathway is required to achieve the optimal level of interhomolog crossovers (4). Both rad51Δ and dmc1Δ mutants exhibit defects in the repair of meiotic DSBs (15). However, Rad51 overexpression overcomes the sporulation defect and spore inviability in dmc1Δ cells (14, 16). This observation and the fact that Rad51 alone is well capable of catalyzing efficient recombination in vegetative cells suggest that the activity of Rad51 is specifically down-regulated in meiosis, so as to ensure the proper level of Dmc1-dependent interhomolog recombination (4, 17).

The meiosis-specific Red1/Hop1/Mek1 protein complex, associated with the axial elements of meiotic chromosomes, has been shown to attenuate inter-sister recombination that is primarily mediated by Rad51 (16, 18, 19). Mutations that compromise the functional integrity of this complex thus lower the frequency of meiotic inter-homolog crossovers and impair chromosome disjunction. A genetic screen for multi-copy suppressors of a hypomorphic red1 mutant allele, red1–22, identified a novel meiosis-specific factor, HED1 (high-copy suppressor of red1). Deletion of HED1 efficiently overcomes the sporulation and DSB repair defects caused by the dmc1Δ mutation, akin to RAD51 overexpression. Likewise, HED1 deletion alleviates the meiotic defects of the hop2Δ mutant. These suppressor attributes of the HED1 deletion are dependent on Rad51. Thus, Hed1 attenuates the Rad51-only HR pathway in meiotic cells. In fact expression of Hed1 in vegetative cells leads to sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents such as methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) due to suppression of Rad51-mediated DNA repair. Hed1 associates with Rad51 (but not with Dmc1) and is targeted to meiotic DSBs in a Rad51-dependent manner (17).

By studying biochemical properties of purified Hed1 in combination with chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), we found that Hed1 does not interfere with Rad51 presynaptic filament assembly but it restricts access of the Swi2/Snf2-related motor protein Rad54 to the Rad51 presynaptic filament. Consequently, Hed1 prevents functional synergy between Rad54 and the Rad51 presynaptic filament in the HR reaction (20). The importance of attenuating Rad51-Rad54 complex activity during meiotic recombination is underscored by the recent finding that phosphorylation of Rad54 on threonine 132 by the meiosis-specific kinase Mek1 reduces the affinity of Rad54 for Rad51. Companion genetic analysis has revealed that the Mek1-mediated regulation of the Rad51-Rad54 complex acts in parallel with the Hed1 regulatory pathway (21).

In this study, we found and characterized several novel biochemical properties of Hed1. Through the isolation of hed1 mutants selectively impaired for the various functional attributes and their biochemical and genetic analyses, we are able to explain how this HR regulator fulfills its biological role. Our results shed light on how budding yeast cells achieve meiotic HR control to favor crossover formation via the Dmc1-dependent pathway.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and Plasmids

Yeast strains used are listed in supplemental Table S1. In Fig. 2, strains PJ69–4A and TBR4606 were used. In Fig. 4A strain PJ69–4A was used. In Fig. 7A, strains TBR2164, 2166, 2168, 2170, 2172, 2182, and 4467 were used. In Fig. 7C, strains TBR4964, 4966, 4970, 4972, 4974, and 4986 were used.

FIGURE 2.

Hed1 self-associates in the presence of Rad51. Yeast two-hybrid analysis of the Hed1-Rad51 and Hed1-Hed1 interactions in wild type and rad51 strains. Medium lacking tryptophan and leucine was used to maintain the DBD fusion plasmid (marked with TRP1) and the AD fusion plasmid (marked with LEU2). Growth on medium lacking adenine or histidine reflects the expression levels of the ADE2 and HIS3 reporters and is thus a measure of the interaction between two fusion proteins. Shown on the right is growth on medium lacking tryptophan and leucine as a reference.

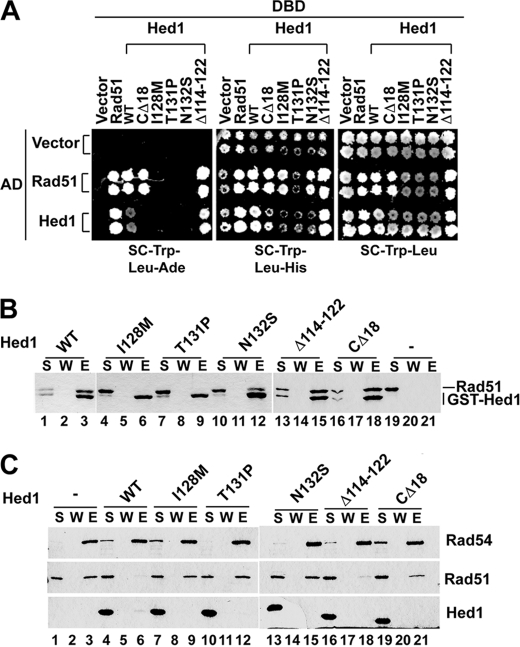

FIGURE 4.

Generation of hed1 mutants defective in Rad51 interaction and self-association. A, yeast two-hybrid analysis of the Hed1-Rad51 and Hed1-Hed1 interactions using wild type and HED1 mutants defective in Rad51 binding (hed1-I128M, hed1-T131P, and hed1-N132S), DNA binding (hed1-Δ114–122), and self-association (hed1-CΔ18). The experiments were performed in PJ69–4A strain (supplemental Table S1). B, Rad51 was incubated with GST-Hed1, the indicated GST-hed1 mutant, or GST. Protein complexes were captured on glutathione-Sepharose beads, which were treated with SDS to elute bound proteins. The supernatant (S), wash (W), and SDS eluate (E) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. C, Rad51 and S-protein tagged Rad54 (27) were incubated with or without (His)6-tagged Hed1 or the indicated hed1 mutant. Protein complexes were captured with S-protein agarose beads. The fractions were analyzed as in B.

FIGURE 7.

Effects of HED1 mutations on mitotic DNA damage sensitivity and meiotic DSB repair. A, cells that harbored either HED1 or the indicated hed1 mutant under the control of the galactose-inducible promoter were serially diluted (5-fold dilutions) and spotted on complete medium containing either dextrose (YPD) or galactose (YPGal) and with the indicated concentration of MMS or phleomycin. B, structure of the HIS4LEU2 recombination hot spot (46). Note that the two species arising from inter-homolog reciprocal recombination are omitted, because they overlap with parental bands and cannot be detected under the electrophoresis conditions employed in C. C, effect of various HED1 mutations on meiotic DSB repair was examined in the dmc1-null mutant. Cells were collected at the indicated times upon entry into meiosis, genomic DNA was extracted, digested with XhoI, subjected to electrophoresis and Southern blotting using the probe shown in B.

Protein Expression Constructs

Various HED1 mutations were introduced using the Quick-Change Site Directed Mutagenesis kit (Agilent technologies) into the following plasmids: pET11-Hed1-(His)6 to generate His-tagged Hed1; pGEX-6P1-Hed1-(His)6 to generate GST-(His)6-tagged Hed1; pTB326-FLAG-Hed1 to generate expression plasmids for ChIP analysis. All of the plasmids were described previously (20).

Generation of Mutant Strains and Plasmids

Gene knock-out and integration of GAL1 promoter right before the HED1 ORF were done as previously described (22). HED1 point mutants were introduced into yeast strains by using the pCORE cassette (23). Specifically, nucleotides from 382 to 447 of the HED1 ORF (the first nucleotide of the first codon is one) were replaced with markers carrying both URA3 and KAN first. Then the strain was transformed with DNA fragments carrying mutated HED1 genes, selected for the loss of the URA3 and KAN markers by using 5-FOA plates, followed by checking G418 sensitivity. DNA fragments carrying mutated HED1 genes were PCR-amplified with the plasmids isolated from the yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) screening (described below) as templates. The pOAD and pOBD2 plasmids (24) carrying the HED1 and RAD51 genes were described before (17). Expression of Hed1 was evaluated by Western blot with affinity purified rabbit polyclonal anti-Hed1 antibody raised against full-length recombinant Hed1.

Screening for HED1 Mutants That Affect Interaction with Itself and Rad51

The DNA fragment carrying the HED1 ORF was randomly mutagenized by PCR and inserted between the PvuII and NcoI sites of the vector pOBD2 (24, 25). The pool of PJ69–4A transformants carrying both a mutagenized HED1 gene in pOBD2 and either RAD51 gene or wild type HED1 gene in the vector pOAD were examined for the activation of the reporter genes ADE2 and HIS3. Clones that failed to or reduced the activation of these reporters were picked for further study. Plasmids were recovered from yeast and used to retransform the PJ69–4A strain along with pOAD-RAD51 or pOAD-HED1 to examine the reproducibility of the phenotypes. The recovered plasmids were sequenced to determine the mutation sites.

Mutagen Sensitivity

To test mutagen sensitivity of the strains carrying galactose-inducible wild type or mutant Hed1 the following strains were used: TBR2182, 2164, 2168, 2170, 2172, and 4467. Overnight cultures in YP+3% glycerol media were diluted to 0.2 at OD660. 5-fold serial dilutions of each strain were spotted (5 μl) on YPD or YP-galactose plates containing indicated amounts of MMS or phleomycin (Sigma). To test mutagen sensitivity of the ChIP strains, JKM179 cells harboring the pTB326 vector with FLAG-tagged wild type or mutant Hed1 (see below) were grown in SC-Trp overnight, diluted (10-fold serial dilutions) in SC-Trp and spotted on SC-Trp plates containing the indicated amount of MMS.

Protein Purification

Expression and purification of wild type and mutant Hed1 proteins that were either tagged with (His)6 or with both GST and (His)6 were performed as described (20). Purification of Rad51 and S protein-tagged (S-tagged) Rad54 followed our published procedures (26, 27). RecA was purchased from New England Biolabs (NEB).

DNA Binding Assay

Wild type or mutant (His)6-tagged Hed1 (0.6, 0.8, 1.2, and 1.5 μm) was incubated with pBluescript SK viral (+) strand DNA (30 μm nucleotides) and pBluescript II SK (+) duplex DNA linearized with BamHI (30 μm base pairs) in buffer A (25 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mm KCl, 100 μg/ml BSA, 5 mm MgCl2) for 10 min at 37 °C. Where indicated, the reactions were de-proteinized with SDS (1% final concentration) and proteinase K (100 μg/ml final concentration). DNA species were resolved by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel in TAE buffer (40 mm Tris acetate, pH 7.4, 0.5 mm EDTA) and stained with ethidium bromide.

BLAST Analysis of Hed1

Homology searches were performed using NCBI BLAST. Hed1 fragments were aligned with T4 endonuclease and HhoI sequences using the T-Coffee software (28, 29).

Rad51 Filament Stabilization Assays

The filament stabilization assay was performed essentially as described (13) with several modifications. To assemble the presynaptic filament biotinylated 83-mer oligo dT (15 μm nucleotides) was incubated with Rad51 (3 μm) or RecA (supplemental Fig. S1C, 6 μm) and with or without wild type or mutant Hed1 (0.75, 1.25, 1.9, and 2.5 μm) in buffer A (25 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mm KCl, 100 μg/ml BSA, 5 mm MgCl2) supplemented with 2.5 mm ATP for 5 min at 37 °C. Then, 83-mer oligo dT (150 μm nucleotides) was added in 1 μl as Rad51 trap, followed by a 20-min incubation. After being mixed with 0.75 μl of Streptavidin magnetic beads (Roche) for 5 min, the Magnetic separator (NEB) was used to capture the beads. Proteins bound to the magnetic beads were eluted in 20 μl of 2% SDS. The supernatant and bead fractions were analyzed by 15% SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining. To verify that the DNA trap remained in the supernatant, the supernatant and bead fractions were incubated with 100 μg/ml of proteinase K at 37 °C for 30 min and then analyzed in a 6% polyacrylamide gel in TBE (89 mm Tris, 89 mm boric acid, pH 8.3, 2 mm EDTA) followed by ethidium bromide staining of DNA. The experiment to examine whether Hed1 stabilizes Rad51-dsDNA filaments was performed as above, except that the streptavidin magnetic beads were coated with biotinylated dsDNA (5 μm base pairs; 600 bp pBluescript II SK (+) PCR product) and non-biotinylated dsDNA (50 μm base pairs; pBluescript II SK (+) DNA linearized with BamHI) was used as the Rad51 trap.

Gel Filtration

Hed1 (60 μg) was analyzed in a 20 ml Sephacryl S-200 column equilibrated in buffer K (20 mm KH2PO4, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mm EDTA, 0.01% Igepal, and 1 mm dithiothreitol) containing 500 mm KCl. Fractions (0.5 ml) were subjected to TCA precipitation followed by SDS-PAGE analysis in 12% polyacrylamide gels and staining with Coomassie Blue.

SAXS Data Collection and Evaluation

SAXS data were collected at the ALS beamline 12.3.1 at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (30). Data were collected at a wavelength λ of 1.0 Å and sample-to-detector distances of 1.5 m, resulting in scattering vectors, q, ranging from 0.01 Å−1 to 0.31 Å−1. The scattering vector is defined as q = 4π sinθ/λ, where θ is the scattering angle. All experiments were performed at 20 °C and data were processed as described (30). Briefly, data were acquired at short and long time exposure (0.5 s, 5 s) for both protein, at a concentration between 0.4 and 4 mg/ml, and relevant buffer. Scattering profiles were generated by subtracting buffer from protein exposures and analysis of Guinier plots (31) at the various protein concentrations showed no signs of aggregation. Data from short and long exposures were then merged to generate SAXS data that include the entire scattering spectrum, which were used for subsequent analyses. The radius of gyration Rg was derived by the Guinier approximation I(q) = I(0) exp(−q2Rg2/3) with the limits qRg<1.3. The program GNOM (32) was used to compute the electron pair-distance distribution function, P(r). This approach also provided the maximum dimension of the macromolecule, Dmax. The overall shapes were restored from the experimental data using the program DAMMIN (33).

MALS Data Collection and Evaluation

Light scattering was performed with a micro volume size-exclusion chromatographic system (Ettan LC, GE Healthcare) connected inline to an 18-angle light scattering and refractive index detector (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara CA) where detector 12 was modified for quasi-elastic light scattering detection. Briefly, 50 μl of Hed1 sample at 3 mg/ml was injected into a 2.4 ml Superdex 75 PC 3.2 column pre-equilibrated in buffer (50 mm KH2PO4 pH 8.0, 0.4 m KCl, 5% glycerol, 2% sucrose, and 2 mm Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) and run at 0.04 μl/min. Band broadening and detector calibration were performed with 10 mg/ml glucose isomerase (Hampton Research) using a refractive index increment of 0.178.

ChIP Assay

Yeast strain JKM179 (34, 35) with C-terminally 13myc-tagged RAD54 (36) was transformed with pTB326 (2μ, ADH1, TRP1) or pTB326 containing wild type or mutated HED1 gene with an N-terminal FLAG tag (pTB326-FLAG-HED1). The expression of Hed1 was verified by Western blot with anti-FLAG-HRP antibody (Sigma). The ChIP experiments were performed as described (20).

Other Assays

Detection of meiotic DSBs was performed as described (17). Affinity pulldown, ATPase, and D-loop assays were performed as described (20, 27).

RESULTS

Stabilization of the Rad51 Presynaptic Filament by Hed1

In our earlier study Hed1 showed no overt negative effect on Rad51 presynaptic filament assembly and, in fact, a significant enhancement of the homologous DNA pairing activity of Rad51 was seen (20). We used a previously devised assay (13) to determine whether Hed1 influences the stability of the Rad51 presynaptic filament. Briefly, the presynaptic filament was assembled with Rad51 (3 μm) on a biotinylated ssDNA oligonucleotide with or without Hed1, and then an excess of free, non-biotinylated oligonucleotide was added to trap Rad51 that had dissociated from the original presynaptic filament. The biotinylated oligo and bound proteins were isolated using streptavidin magnetic resin and analyzed (Fig. 1A). The results showed that Hed1 exerts a strong stabilizing effect on the presynaptic filament, such that greater than 80% of Rad51 remained associated with the magnetic resin in the presence of 2.5 μm Hed1, whereas without Hed1 essentially all of Rad51 had dissociated and was trapped on the non-biotinylated DNA (Fig. 1B). We verified that (a) Rad51 did not associate with the magnetic resin in the absence of the biotinylated oligonucleotide (Fig. 1B), (b) the DNA trap stayed in the supernatant fraction (supplemental Fig. S1A), (c) without the DNA trap, Rad51 remained bound to the biotinylated ssDNA even in the absence of Hed1 (supplemental Fig. S1B), and, importantly, (d) Hed1 did not stabilize the RecA-ssDNA filament (supplemental Fig. S1C).

FIGURE 1.

Rad51 filament stabilization and DNA binding activities of Hed1. A, schematic of the Rad51 presynaptic filament stabilization assay. Black circle represents biotin, gray oval with white center represents streptavidin magnetic beads. B, Rad51 (3 μm) was incubated with or without biotinylated ss oligo-dT (83-mer, 15 μm nucleotides) and (His)6-tagged Hed1 (0.75, 1.25, 1.9, and 2.5 μm). An excess of non-biotinylated ssDNA was added followed by incubation with streptavidin magnetic beads. The supernatant (SN) and bead fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. C, (His)6-tagged Hed1 (0.6, 0.8, 1.2, and 1.5 μm) was incubated with pBluescript ssDNA (30 μm nucleotides) or linear dsDNA (30 μm base pairs) or the mixture of the DNAs. After electrophoresis in an agarose gel the DNA was stained with ethidium bromide. The asterisk (*) denotes treatment with SDS and proteinase K. D, alignment of Hed1 against HhoI (top panel) and T4 endonuclease (bottom panel) revealed sequence similarity. Identical and related residues are indicated by (*) and (:), respectively. The Hed1 region chosen for mutagenesis is boxed. E, purified (His)6-tagged Hed1 and hed1-Δ114–122 were incubated with pBluescript ssDNA and analyzed as in C.

DNA Binding by Hed1 and Mutant Isolation

Recombination accessory and regulatory factors often have an ability to bind DNA (9), so we tested Hed1 for such an attribute. In a DNA mobility shift assay, Hed1 clearly bound ssDNA but was less capable of binding dsDNA (Fig. 1C). We note that while discrete nucleoprotein species were formed at low Hed1 concentrations, nucleoprotein complexes made at the higher protein concentrations were retained in the well of the gel, indicating that Hed1 either promotes the formation of DNA networks or binds DNA cooperatively.

A BLAST analysis helped identify sequence similarity of a Hed1 region to Hho1 (the yeast Histone H1 ortholog) and T4 endonuclease (Fig. 1D). Accordingly, an internally truncated mutant deleting residues 114–121 predicted to be critical for DNA binding was constructed, expressed, and purified as for the wild type counterpart in either GST-(His)6-tagged or (His)6-tagged form (supplemental Fig. S2A). Importantly, the hed1-Δ114–122 mutant protein is attenuated for DNA binding (Fig. 1E) but proficient in Rad51 interaction (see below).

Hed1 Self-association in Yeast Cells Is Rad51-dependent

We previously found Hed1-Rad51 and Hed1-Hed1 interactions in the Y2H system (17). Interestingly, the Hed1 self-association was lost upon deletion of RAD51 from the host strain (Fig. 2), suggesting that the interaction between Hed1 molecules occurs when Hed1 is bound to Rad51. As we will document later, the isolation of specific HED1 mutants has allowed us to conclude that self-association and Rad51 interaction are mediated by different regions of Hed1.

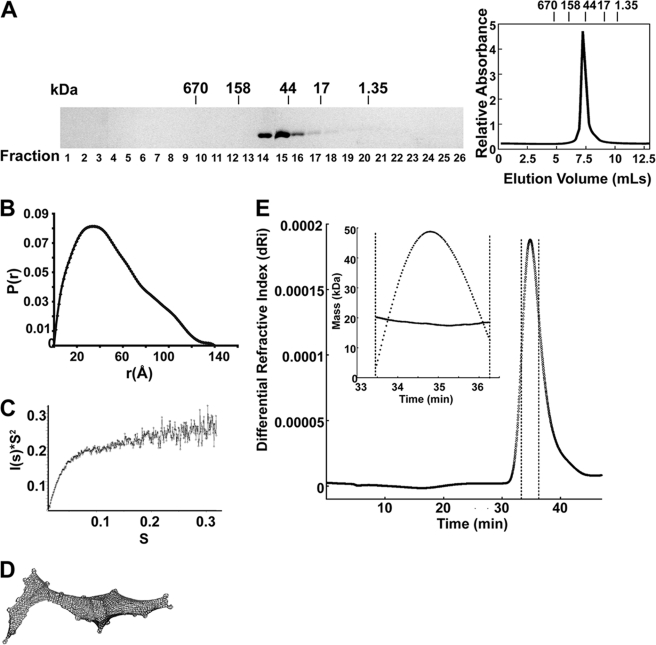

Structural Analysis of Purified Hed1

Hed1 (19.2 kDa predicted size) elutes from a gel filtration column with an apparent size of >40 kDa, suggesting that it is either dimeric or an elongated monomer (Fig. 3A). To distinguish between these possibilities, we performed SAXS analysis of purified Hed1 (Fig. 3, B–D). Using Primus Porod analysis (37) the molecular weight of Hed1 was estimated to be 20 kDa, which corresponds to a monomer. The electron pair distribution plot of Hed1 (Fig. 3B) gives a radius of gyration (Rg) = 39.9 Å and maximum distance (Dmax) = 180 Å. These measurements are large for a 20 kDa globular protein, suggesting that Hed1 is elongated in solution (38). This conclusion is further supported by both the plateau observed in the Kratky plot (Fig. 3C), which is characteristic of extended proteins (38), and the extended shape observed from ab initio shape reconstruction using the DAMMIN software (37) (Fig. 3D). Multi-angle light scattering (MALS) analysis also found the size of Hed1 to be 20 kDa (Fig. 3E). Overall, our analyses of Hed1 indicate that it is an elongated monomer. These data support the Y2H results showing that Hed1 self-associates only in the presence of Rad51.

FIGURE 3.

Structural analysis of purified Hed1 in solution. A, gel filtration profile of Hed1. Hed1 (60 μg) was loaded onto a 20 ml Sephacryl S-200 column. The molecular weight standards were: bovine thyroglobulin (670 kDa), bovine γ-globulin (158 kDa), chicken ovalbumin (44 kDa), horse myoglobin (17 kDa), and Vitamin B12 (1.35 kDa). B–D, SAXS analysis of Hed1. B, electron pair-distribution functions P(r) of Hed1, r(Å) - electron distance, Angstroms. C, Kratky plot analysis of Hed1, I, intensity, s, momentum transfer calculated as s = (4πsinθ)/λ, where λ − wavelength of incident x-ray beam, and θ − scattering angle. D, ab initio shape prediction of Hed1 calculated using the DAMMIN software (37). E, MALS analysis of Hed1. Major plot: differential refractive index (dRi) versus time. The Hed1 peak is highlighted. Inset: Hed1 peak area zoomed: solid line shows molecular weight calculated by MALS versus time.

Isolation of hed1 Mutants Defective in Y2H Self-association and Rad51 Interaction

We made use of the Y2H system as a tool to isolate four HED1 point mutants defective in Rad51 interaction. Interestingly, these mutations are clustered within a narrow region spanning residues 128 to 132, corresponding to the following amino acid changes: I128M, T131P, N132S, and N132I. These point mutants are also deficient in Hed1-Hed1 self-association (Fig. 4A, right panel), which again supports the premise that Hed1 self-associates upon complex formation with Rad51. One Hed1 self-association mutant was isolated, which corresponds to a truncation mutation deleting the last 18 residues of the protein. Importantly, this mutant (hed1-CΔ18) retains the ability to interact with Rad51. We note that the DNA binding mutant hed1-Δ114–122 is proficient in both Rad51 interaction and self-association (Fig. 4A, right panel).

In Vitro Validation of HED1 Mutations That Ablate Rad51 Interaction

The point mutations and CΔ18 truncation mutation from the Y2H mutagenic screen were introduced into GST-(His)6 and (His)6-tagged forms of Hed1. While the I128M, T131P, N132S, and CΔ18 mutant proteins could be purified with a similar yield as the wild type counterpart (supplemental Fig. S2A), we could obtain only a small amount of either tagged form of the N132I mutant, and the purified protein aggregated readily. For this reason, the N132I mutant was not included in our biochemical analyses. By affinity pulldown through the GST tag, we found that hed1-I128M and hed1-T131P are defective in Rad51 interaction, while hed1-N132S retains residual Rad51-interacting activity. We also verified that hed1-Δ114–122 and hed1-CΔ18 are proficient in Rad51 interaction (Fig. 4B). Importantly, we showed that, unlike Δ114–122 (Fig. 1C), all the other Hed1 mutants possess DNA binding activity, even though hed1-CΔ18 is much less adept at producing nucleoprotein complexes that are retained in the gel well (supplemental Fig. S2B).

Effects of HED1 Mutations on the Formation of the Rad51-Rad54 Complex

We showed previously that Hed1 prevents the assembly of the Rad51-Rad54 complex (20). We used affinity pulldown to evaluate the ability of the purified hed1 mutants to interfere with Rad51-Rad54 complex formation (Fig. 4C). Importantly, the results revealed that all three Rad51-interaction deficient mutants (i.e. I128M, T131P, and N132S) and also the self-association hed1-CΔ18 mutant are incapable of interfering with Rad51-Rad54 complex formation (Fig. 4C). We found, however, that the DNA binding hed1-Δ114–122 mutant is proficient in this regard (Fig. 4C).

Effects of HED1 Mutations on the Functionality of the Rad51-Rad54 Complex

Rad51 enhances the ATPase activity of Rad54 and the ability of Rad51 to make D-loops is stimulated by Rad54 (39, 40). By preventing Rad51-Rad54 complex formation, Hed1 suppresses the functional synergy between Rad51 and Rad54 (20). Consistent with results from the affinity pulldown assay, the hed1 mutants that are impaired for Rad51 interaction (I128M, T131P, and N132S) or self-association (CΔ18) did not interfere with Rad51-Rad54 synergy in either the ATPase (Fig. 5A) or D-loop reaction (Fig. 5, B and C). Interestingly, the DNA binding Δ114–122 mutant was able to partly diminish ATP hydrolysis by the Rad54-Rad51 complex, with more pronounced effects seen at higher concentrations of the mutant (Fig. 5A). In the D-loop reaction also, a partial inhibition by hed1-Δ114–122 was seen when a higher Hed1 to Rad54 ratio was used (Fig. 5D).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of HED1 mutations on Rad51-Rad54 complex activity. A, ATP hydrolysis by Rad54 (5.3 nm) was examined with or without Rad51 (130 nm) and either (His)6-tagged Hed1 or the indicated hed1 mutant (100 nm, left panel; 400 nm, right panel). Quantifications were based on three independent experiments, with error bars representing S.E. B, schematic of the D-loop reaction (27). C, D-loop formation by Rad51 and Rad54 with or without (His)6-tagged Hed1 or the indicated hed1 mutant. Rad51 (1.3 μm) was incubated with radiolabeled ss 90-mer oligo (3 μm nucleotides) followed by the addition of Rad54 (400 nm) and wild type or mutant Hed1 (0.5, 1, and 1.5 μm) as indicated. pBluescript SK replicative form I DNA (45 μm base pairs) was added to start the reaction. Quantifications were based on three independent experiments, with error bars representing S.E. D, D-loop reactions performed as in C but with 83 nm of Rad54 and 1.5 μm of Hed1 or the indicated hed1 mutant. Quantifications were based on three independent experiments, with error bars representing S.E.

Dependence of Rad51 Filament Stabilization on the Functional Attributes of Hed1

We asked how the various HED1 mutations affect the ability of Hed1 to stabilize the Rad51 presynaptic filament. The results showed that impairing any of the functional attributes of Hed1, i.e. Rad51 interaction, DNA binding, or self-association, abolishes Hed1's ability to stabilize the Rad51 presynaptic filament (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Effects of HED1 mutations on Rad51 filament stabilization. Rad51 filament stabilization by (His)6-tagged Hed1 or the indicated hed1 mutant. The experiment was performed as in Fig. 1B. Quantifications (right panel) were based on three independent experiments, with error bars representing S.E.

Genetic Effects of HED1 Mutations

Expression of Hed1 in vegetative cells inhibits Rad51-dependent HR (17). To test the HED1 mutations, we placed the mutant genes under the control of the galactose-inducible promoter, so that only cells growing on galactose-containing media would express the mutant. By immunoblotting, we established that all the mutant proteins were present at a level similar to that of the wild type counterpart (supplemental Fig. S3A). While Hed1 expression sensitized cells to MMS and phleomycin, the expression of hed1 mutants defective in either Rad51 interaction (I128M, T131P, and N132S) or in self-association (CΔ18) had little or no effect. Interestingly, mild DNA damage sensitization was seen upon expression of the DNA binding mutant, hed1-Δ114–122 (Fig. 7A).

Meiotic DSBs made by Spo11 are repaired poorly in the dmc1Δ mutant. Deletion of HED1 in the dmc1Δ background, however, restores efficient DSB repair by allowing the use of the Rad51-dependent HR pathway (17). We evaluated the impact of the various HED1 mutations on the ability of Hed1 to attenuate the Rad51-dependent pathway by monitoring the repair kinetics of Spo11-made breaks at the HIS4LEU2 meiotic recombination hotspot (Fig. 7B). As expected, while DSBs persisted in dmc1Δ cells even after 11 h, they were efficiently repaired in the dmc1Δ hed1Δ double mutant (Fig. 7C). Importantly, dmc1Δ cells that harbored any one of the three Hed1 mutations that abolish Rad51 binding or the CΔ18 self-association mutation were as proficient in DSB repair as the dmc1Δ hed1Δ mutant (Fig. 7C). As in the case of the mitotic drug sensitivity test above (Fig. 7A), the hed1-Δ114–122 DNA binding mutant showed an intermediate phenotype: the breaks were repaired but with delayed kinetics (Fig. 7C). Immunoblot analysis revealed that all hed1 mutant proteins were expressed at a similar level as the wild type protein (supplemental Fig. S3B).

Effects of HED1 Mutations on the DSB Recruitment of Rad54

Our cytological analysis had revealed that Hed1 is recruited to meiotic DSBs in a Rad51-dependent manner (17). By ChIP, we had also demonstrated that, when expressed in mitotic cells, Hed1 is targeted to a site-specific DSB made by the HO endonuclease in a Rad51-dependent manner and it prevents Rad54 recruitment (20). In this study, we carried out ChIP in mitotic cells to analyze the targeting of the various hed1 mutant proteins to the HO break and also their effects on Rad54 recruitment. As determined by immunoblotting, all the mutants were expressed to a similar level as the wild type protein in the yeast strain used (supplemental Fig. S4A). There was a varying degree of impairment in the DSB targeting of mutant hed1 proteins defective in the Rad51 interaction (I128M, T131P, and N132S), with the strongest effect seen for the T131P mutant (Fig. 8). However, the DNA binding and self-association hed1 mutants (Δ114–122 and CΔ18, respectively) were recruited at nearly the wild type level (Fig. 8). Consistent with our previous report (20), Rad54 recruitment was suppressed strongly by Hed1, but, of the five hed1 mutants, only hed1-Δ114–122 was able to reduce Rad54 recruitment (Fig. 8). We note that only wild type Hed1 and, to a lesser degree, hed1-Δ114–122 sensitized the ChIP yeast strain to MMS (supplemental Fig. S4B).

FIGURE 8.

Effects of Hed1 mutations on DSB targeting of Rad54. JKM179 cells that express Myc-tagged Rad54 (36) were transformed with the pTB326 vector (ADH promoter), with pTB326-FLAG-HED1, or pTB326-FLAG-hed1 mutants as indicated. The DSB recruitment of Hed1 and Rad54 to MAT Z was evaluated at 4 h after the induction of an HO break. The MAT Z signal was quantified as described (36). Quantifications were based on three independent experiments, with error bars representing S.E.

DISCUSSION

Multiple mechanisms help ensure that the proper level of inter-homolog bias is achieved in the repair of programmed meiotic DSBs by HR (16, 18, 19). Moreover, the recombinases Dmc1 and Rad51 act together to direct the repair of DSBs using the homologous chromosome, rather than the sister chromatid, as partner (4). In the absence of Dmc1, Rad51-dependent recombination is inhibited via two parallel mechanisms: (a) phosphorylation of Rad54 by the Mek1 kinase weakens its interaction with Rad51; (b) prevention of Rad51-Rad54 complex formation by Hed1 (17, 20, 21). As discussed below, by examining wild type Hed1 and several separation-of-function hed1 mutants, we have uncovered novel attributes of Hed1 and provided mechanistic insights into the meiotic HR regulatory role of this interesting molecule.

Notable Properties of Hed1

We have provided evidence that Hed1 is an elongated monomer in solution. Moreover, we have found that Hed1 binds DNA, and that it stabilizes the Rad51 presynaptic filament. In the Y2H test, Hed1 undergoes self-association. Two lines of evidence suggest that Hed1-Hed1 intermolecular contact is dependent on Rad51. First, Hed1 self-association no longer occurs when RAD51 is deleted, and second, mutations that compromise the ability of Hed1 to interact with Rad51 also ablate Hed1 self-association. The C terminus of Hed1 is important for self-association, as deletion of the last 18 residues, as in the CΔ18 mutation, abolishes self-association without a negative impact on either DNA binding or Rad51 interaction. Whether Hed1 self-association occurs upon interaction with Rad51 in the absence of DNA or only when Rad51 is DNA-bound remains to be established. Likewise, we do not yet know if the Hed1-Hed1 complex possesses a fixed stoichiometry.

Relevance of the Hed1-Rad51 Complex, Hed1 Self-association, and Hed1 DNA Binding

We have isolated several HED1 point mutations within residues 128–132 that impair the ability of Hed1 protein to undergo Y2H and in vitro interaction with Rad51. None of the three hed1 mutants is able to prevent Rad51-Rad54 complex formation or functional synergy, and, accordingly, the expression of these HED1 mutants in vegetative cells fails to sensitize cells to DNA-damaging agents and exerts a lesser inhibitory effect on the recruitment of Rad54 to a HO-made DSB than does wild type Hed1. Moreover, in meiosis, dmc1Δ cells harboring these hed1 alleles repair Spo11-made DSBs just as efficiently as dmc1Δ hed1Δ cells. Our ChIP analysis revealed significant association of these mutant hed1 proteins with the HO-made DNA break. Because the DSB association of Hed1 is Rad51-dependent, it appears that these mutant hed1 proteins possess a residual affinity for Rad51 and/or the Rad51 presynaptic filament in cells. Alternatively, the ChIP analysis may be sensitive enough to detect even a small amount of DSB-associated hed1 mutants.

We note that Hed1 self-association is also indispensable for biological activity, as the hed1-CΔ18 mutant fails to interfere with the physical and functional interactions of the Rad51-Rad54 pair in vitro or the DSB recruitment of Rad54 in cells. Likewise, expression of this mutant does not sensitize cells to DNA-damaging treatment, nor does it prevent dmc1Δ hed1Δ cells from repairing Spo11-made DSBs in meiosis. Thus, Hed1 self-association appears to reinforce the Rad51-Hed1 complex stability. As revealed by ChIP, this hed1 mutant can associate with DSBs in cells.

Interestingly, the hed1-Δ114–122 DNA binding mutant retains partial Hed1 activity in various biochemical assays designed to test for physical and functional interactions of the Rad51-Rad54 pair. Accordingly, in ChIP experiments, concomitant with the targeting of this hed1 mutant to DSBs, the recruitment of Rad54 is diminished. Moreover, expression of this mutant in mitotic cells engenders moderate mutagen sensitivity and the repair of meiotic DSBs in dmc1Δ strain becomes delayed in the presence of hed1-Δ114–122 as the only HED1 allele. Overall, it appears that DNA binding plays a secondary role in reinforcing the complex of Hed1 with the Rad51 filament. The Hed1 DNA binding activity seems to be important for Rad51 filament stabilization (see next section).

Possible Function and Mechanism of Hed1-mediated Rad51 Presynaptic Filament Stabilization

Hed1 exerts no adverse effect on the assembly of the Rad51 presynaptic filament (20) and, in fact, a presynaptic filament stabilization function has been revealed for Hed1 herein. Thus, Hed1 appears to keep the Rad51 presynaptic filament in a stable but inactive or “idle” status. There are at least two possible functional implications for this Hed1 attribute. First, a Hed1-Rad51-ssDNA co-filament might serve as a platform for subsequent loading of Dmc1 onto DNA, since the association of Dmc1 with meiotic chromosomes largely depends on Rad51 (41). Moreover, it has been proposed that, while the first end of a resected DSB invades a homologous duplex, the second end of the same break must remain quiescent until its capture that results in the formation of a double Holliday structure. Hed1 has been suggested to play a role in the maintenance of the second-end quiescence (42). In this scenario, Hed1 would help maintain the Rad51 presynaptic filament on the second DNA end while preventing the recruitment of Rad54 and the invasion of the sister chromatid.

While ATP binding by Rad51 is required for presynaptic filament assembly, the hydrolysis of ATP prompts the turnover of Rad51 protomers from the filament (43, 44). Hed1 does not affect the rate of ATP hydrolysis by Rad51 (20), so what is the mechanism of the presynaptic stabilization activity of Hed1? One possibility is that, because of the ability of Hed1 to simultaneously interact with both Rad51 and ssDNA, Rad51 protomers that have dissociated from ssDNA remain tethered to the Hed1-ssDNA complex, thus facilitating the re-assembly of the presynaptic filament.

Interestingly, we have found that Hed1 also stabilizes Rad51 filaments assembled on dsDNA (supplemental Fig. S1D). This attribute of Hed1 may limit the amount of Rad51 available for HR by sequestering the recombinase on bulk chromatin. Alternatively, or in addition, Hed1 may prevent the dissociation of Rad51 from the primer end in the nascent D-loop, so as to delay the initiation of repair DNA synthesis.

Concluding Remarks

The Hop2-Mnd1 complex and Rad54 protein have been shown to stabilize the Rad51 presynaptic filament. We note, however, that these Rad51 accessory factors serve to upregulate the recombinase activity of Rad51 (9). In contrast, the presynaptic filament stabilization function of Hed1 enhances the ability of Hed1 to preclude access by Rad54, and as we have speculated, may keep the Rad51 presynaptic filament assembled on the second DNA end of a DSB in a quiescent state. Moreover, stabilization of Rad51-dsDNA filaments by Hed1 may impose another layer of regulatory control over the activity of Rad51.

In meiosis, an excess of DSBs are introduced by Spo11 to ensure that at least one crossover occurs between every pair of homologous chromosomes. A large fraction of these Spo11-made DSBs are eventually eliminated via the Rad51-dependent HR pathway, as revealed in studies done in fission yeast (45). It will be of considerable interest to investigate how the Hed1-mediated block is alleviated to allow the completion of meiotic DSB repair via the Rad51-only pathway.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Research Grants R01ES07061, R01ES015632, and R01GM57814 (to P. S.) and R01GM098510 (to M. G. S.), Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award GM079816 (to V. B.), Marie Curie Cancer Care Transitional Programme Grant (to H. T.), and by Clemson University (to M. G. S.).

This article contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S4.

- DSB

- DNA double-strand break

- Hed

- high copy suppressor of red

- MMS

- methyl methanesulfonate

- Y2H

- yeast two-hybrid

- SAXS

- small angle x-ray scattering

- MALS

- multi-angle light scattering.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bishop D. K., Zickler D. (2004) Early decision; meiotic crossover interference prior to stable strand exchange and synapsis. Cell 117, 9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neale M. J., Keeney S. (2006) Clarifying the mechanics of DNA strand exchange in meiotic recombination. Nature 442, 153–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Keeney S., Giroux C. N., Kleckner N. (1997) Meiosis-specific DNA double-strand breaks are catalyzed by Spo11, a member of a widely conserved protein family. Cell 88, 375–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sheridan S., Bishop D. K. (2006) Red-Hed regulation: recombinase Rad51, though capable of playing the leading role, may be relegated to supporting Dmc1 in budding yeast meiosis. Genes Dev. 20, 1685–1691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sung P., Klein H. (2006) Mechanism of homologous recombination: mediators and helicases take on regulatory functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 739–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu L., Hickson I. D. (2006) DNA helicases required for homologous recombination and repair of damaged replication forks. Annu. Rev. Genet. 40, 279–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bianco P. R., Tracy R. B., Kowalczykowski S. C. (1998) DNA strand exchange proteins: a biochemical and physical comparison. Front Biosci. 3, D570–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Symington L. S. (2002) Role of RAD52 epistasis group genes in homologous recombination and double-strand break repair. Microbiol Mol. Biol. Rev. 66, 630–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. San Filippo J., Sung P., Klein H. (2008) Mechanism of eukaryotic homologous recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 229–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pâques F., Haber J. E. (1999) Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol. Biol. Rev. 63, 349–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen Y. K., Leng C. H., Olivares H., Lee M. H., Chang Y. C., Kung W. M., Ti S. C., Lo Y. H., Wang A. H., Chang C. S., Bishop D. K., Hsueh Y. P., Wang T. F. (2004) Heterodimeric complexes of Hop2 and Mnd1 function with Dmc1 to promote meiotic homolog juxtaposition and strand assimilation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 10572–10577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Petukhova G. V., Pezza R. J., Vanevski F., Ploquin M., Masson J. Y., Camerini-Otero R. D. (2005) The Hop2 and Mnd1 proteins act in concert with Rad51 and Dmc1 in meiotic recombination. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 449–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chi P., San Filippo J., Sehorn M. G., Petukhova G. V., Sung P. (2007) Bipartite stimulatory action of the Hop2-Mnd1 complex on the Rad51 recombinase. Genes Dev. 21, 1747–1757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tsubouchi H., Roeder G. S. (2003) The importance of genetic recombination for fidelity of chromosome pairing in meiosis. Dev. Cell 5, 915–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rockmill B., Sym M., Scherthan H., Roeder G. S. (1995) Roles for two RecA homologs in promoting meiotic chromosome synapsis. Genes Dev. 9, 2684–2695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bishop D. K., Nikolski Y., Oshiro J., Chon J., Shinohara M., Chen X. (1999) High copy number suppression of the meiotic arrest caused by a dmc1 mutation: REC114 imposes an early recombination block and RAD54 promotes a DMC1-independent DSB repair pathway. Genes Cells 4, 425–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tsubouchi H., Roeder G. S. (2006) Budding yeast Hed1 down-regulates the mitotic recombination machinery when meiotic recombination is impaired. Genes Dev. 20, 1766–1775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schwacha A., Kleckner N. (1997) Interhomolog bias during meiotic recombination: meiotic functions promote a highly differentiated interhomolog-only pathway. Cell 90, 1123–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu L., Weiner B. M., Kleckner N. (1997) Meiotic cells monitor the status of the interhomolog recombination complex. Genes Dev. 11, 106–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Busygina V., Sehorn M. G., Shi I. Y., Tsubouchi H., Roeder G. S., Sung P. (2008) Hed1 regulates Rad51-mediated recombination via a novel mechanism. Genes Dev. 22, 786–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Niu H., Wan L., Busygina V., Kwon Y., Allen J. A., Li X., Kunz R. C., Kubota K., Wang B., Sung P., Shokat K. M., Gygi S. P., Hollingsworth N. M. (2009) Regulation of meiotic recombination via Mek1-mediated Rad54 phosphorylation. Mol. Cell 36, 393–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Longtine M. S., McKenzie A., 3rd, Demarini D. J., Shah N. G., Wach A., Brachat A., Philippsen P., Pringle J. R. (1998) Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14, 953–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Storici F., Lewis L. K., Resnick M. A. (2001) In vivo site-directed mutagenesis using oligonucleotides. Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 773–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hudson J. R., Jr., Dawson E. P., Rushing K. L., Jackson C. H., Lockshon D., Conover D., Lanciault C., Harris J. R., Simmons S. J., Rothstein R., Fields S. (1997) The complete set of predicted genes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae in a readily usable form. Genome Res. 7, 1169–1173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tsubouchi H., Roeder G. S. (2002) The Mnd1 protein forms a complex with hop2 to promote homologous chromosome pairing and meiotic double-strand break repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 3078–3088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sung P., Stratton S. A. (1996) Yeast Rad51 recombinase mediates polar DNA strand exchange in the absence of ATP hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 27983–27986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Raschle M., Van Komen S., Chi P., Ellenberger T., Sung P. (2004) Multiple interactions with the Rad51 recombinase govern the homologous recombination function of Rad54. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 51973–51980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Notredame C., Higgins D. G., Heringa J. (2000) T-Coffee: A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 302, 205–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Poirot O., O'Toole E., Notredame C. (2003) Tcoffee@igs: A web server for computing, evaluating, and combining multiple sequence alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3503–3506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hura G. L., Menon A. L., Hammel M., Rambo R. P., Poole F. L., 2nd, Tsutakawa S. E., Jenney F. E., Jr., Classen S., Frankel K. A., Hopkins R. C., Yang S. J., Scott J. W., Dillard B. D., Adams M. W., Tainer J. A. (2009) Robust, high-throughput solution structural analyses by small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). Nat. Methods 6, 606–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guinier A., Fournet G. (1955) Small-angle Scattering of X-rays, Wiley, New York [Google Scholar]

- 32. Svergun D. I. (1992) Determination of the regularization parameter in indirect-transform methods using perceptual criteria. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 25, 495–503 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Svergun D. I., Petoukhov M. V., Koch M. H. (2001) Determination of domain structure of proteins from X-ray solution scattering. Biophys. J. 80, 2946–2953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moore J. K., Haber J. E. (1996) Capture of retrotransposon DNA at the sites of chromosomal double-strand breaks. Nature 383, 644–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sugawara N., Wang X., Haber J. E. (2003) In vivo roles of Rad52, Rad54, and Rad55 proteins in Rad51-mediated recombination. Mol. Cell 12, 209–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wolner B., van Komen S., Sung P., Peterson C. L. (2003) Recruitment of the recombinational repair machinery to a DNA double-strand break in yeast. Mol. Cell 12, 221–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Svergun D. I. (1999) Restoring low resolution structure of biological macromolecules from solution scattering using simulated annealing. Biophys. J. 76, 2879–2886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Putnam C. D., Hammel M., Hura G. L., Tainer J. A. (2007) X-ray solution scattering (SAXS) combined with crystallography and computation: defining accurate macromolecular structures, conformations, and assemblies in solution. Q Rev. Biophys. 40, 191–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Petukhova G., Stratton S. A., Sung P. (1999) Single strand DNA binding and annealing activities in the yeast recombination factor Rad59. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 33839–33842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Van Komen S., Petukhova G., Sigurdsson S., Stratton S., Sung P. (2000) Superhelicity-driven homologous DNA pairing by yeast recombination factors Rad51 and Rad54. Mol. Cell 6, 563–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bishop D. K. (1994) RecA homologs Dmc1 and Rad51 interact to form multiple nuclear complexes prior to meiotic chromosome synapsis. Cell 79, 1081–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim K. P., Weiner B. M., Zhang L., Jordan A., Dekker J., Kleckner N. (2010) Sister cohesion and structural axis components mediate homolog bias of meiotic recombination. Cell 143, 924–937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chi P., Van Komen S., Sehorn M. G., Sigurdsson S., Sung P. (2006) Roles of ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis in human Rad51 recombinase function. DNA Repair 5, 381–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen Z., Yang H., Pavletich N. P. (2008) Mechanism of homologous recombination from the RecA-ssDNA/dsDNA structures. Nature 453, 489–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hyppa R. W., Smith G. R. (2010) Crossover invariance determined by partner choice for meiotic DNA break repair. Cell 142, 243–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hunter N., Kleckner N. (2001) The single-end invasion: an asymmetric intermediate at the double-strand break to double-holliday junction transition of meiotic recombination. Cell 106, 59–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.