Background: P-glycoprotein is an ATP-binding cassette transporter involved in multidrug resistance.

Results: The two nucleotide binding domains are found to be in close association during the catalytic cycle as determined by fluorescence spectroscopy.

Conclusion: Small distance changes were observed during ATP hydrolysis supporting an alternating site mechanism.

Significance: Understanding the mechanism of P-glycoprotein is pertinent for developing inhibitors aimed at overcoming multidrug resistance.

Keywords: ABC Transporter, ATPases, Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), Membrane Proteins, Membrane Transport, Multidrug Transporters, Single Molecule Biophysics

Abstract

P-glycoprotein (Pgp), a member of the ATP-binding cassette transporter family, functions as an ATP hydrolysis-driven efflux pump to rid the cell of toxic organic compounds, including a variety of drugs used in anticancer chemotherapy. Here, we used fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) spectroscopy to delineate the structural rearrangements the two nucleotide binding domains (NBDs) are undergoing during the catalytic cycle. Pairs of cysteines were introduced into equivalent regions in the N- and C-terminal NBDs for labeling with fluorescent dyes for ensemble and single-molecule FRET spectroscopy. In the ensemble FRET, a decrease of the donor to acceptor (D/A) ratio was observed upon addition of drug and ATP. Vanadate trapping further decreased the D/A ratio, indicating close association of the two NBDs. One of the cysteine mutants was further analyzed using confocal single-molecule FRET spectroscopy. Single Pgp molecules showed fast fluctuations of the FRET efficiencies, indicating movements of the NBDs on a time scale of 10–100 ms. Populations of low, medium, and high FRET efficiencies were observed during drug-stimulated MgATP hydrolysis, suggesting the presence of at least three major conformations of the NBDs during catalysis. Under conditions of vanadate trapping, most molecules displayed high FRET efficiency states, whereas with cyclosporin, more molecules showed low FRET efficiency. Different dwell times of the FRET states were found for the distinct biochemical conditions, with the fastest movements during active turnover. The FRET spectroscopy observations are discussed in context of a model of the catalytic mechanism of Pgp.

Introduction

ATP-binding cassette (ABC)2 transporters constitute a superfamily of membrane proteins that couple the hydrolysis of MgATP to substrate translocation across a lipid bilayer (1–3). In bacteria, ABC transporters can function in either import or export of nutrients and toxic molecules, respectively, whereas in eukaryotes, transport occurs exclusively in the direction of export (4). The 48 human ABC transporters are responsible for the transmembrane transport of structurally diverse compounds such as bile acids, carbohydrates, nucleosides, sterols, peptides, inorganic ions, and environmental toxins (5). An important member of the mammalian ABC transporter family is P-glycoprotein, a 170-kDa plasma membrane protein that is involved in the export of a large variety of structurally unrelated organic molecules (6, 7). Human P-glycoprotein (Pgp; ABCB1; MDR1) is expressed in tissues that function in detoxification such as liver, placenta, and the blood-brain barrier. In certain cancers, high level expression of Pgp (along with other ABC transporters such as MRP1 and ABCG2) in the plasma membrane can result in the failure of chemotherapy by preventing the mostly hydrophobic anticancer drugs from entering the cytoplasm or the nucleus, resulting in what is known as multidrug resistance (8–10).

Many eukaryotic ABC transporters, including Pgp, are expressed as single polypeptides organized in four domains as follows: two 6 α-helix transmembrane domains (TMD) and two cytoplasmic nucleotide binding domains (NBDs). The four domains of Pgp are arranged in the order N-TMD1-NBD1-TMD2-NBD2-C with an ∼60-amino acid-long linker connecting NBD1 and TMD2 (11). To carry out productive MgATP hydrolysis coupled to drug transport, the two NBDs have to interact in a head-to-tail fashion, thereby sequestering the nucleotide(s) at the NBD1-NBD2 interface. In this so-called “sandwich” configuration, nucleotide is interacting with the phosphate binding loop (P-loop) of one NBD and the ABC signature motif (LSGGQ) of the other NBD and vice versa. High affinity binding of transport substrate (hereafter referred to as “drug”) occurs in an amphipathic cavity that is formed by the two TMDs toward the cytoplasmic side of the transporter (11). The drug-binding cavity can accommodate a large variety of structurally unrelated molecules and exhibits distinct (but overlapping) binding regions for different subsets of compounds (e.g. the “H” and “R” sites) (12); simultaneous binding of two drug molecules has been reported for Pgp (11–14).

Despite ongoing efforts, the mechanism by which transport of drug (from the inner to the outer leaflet of the membrane) is coupled to the hydrolysis of one or two molecules of ATP is still not fully understood. Several models have been proposed based on a combination of site-directed mutagenesis and biochemical experiments involving transport assays and trapping of catalytic intermediates using inorganic vanadate (Vi) or fluoroaluminate followed by photoaffinity labeling with 8-azido-nucleotide analogs (15–20). These studies revealed that the two NBDs act in a cooperative manner in that mutating of a catalytically essential residue in only one of the two NBDs resulted in virtually complete loss of drug-stimulated ATPase activity. However, some aspects of the mechanism such as the number of ATP molecules hydrolyzed for each transport event and whether the NBDs have to come apart to enable nucleotide and/or drug binding remain controversial.

Over the last few years, crystal structures have been determined for a number of bacterial ABC transporters, and these structural models have provided a molecular picture of some of the catalytic intermediates. According to the current mechanistic model for ABC transporter function (11, 21), Pgp can exist in at least two major conformations during the catalytic cycle as follows: an “inward”-facing conformation, with the drug binding pocket exposed to the cytoplasmic side and separated NBDs, and an “outward”-facing conformation with a low affinity drug-binding site exposed to the extracellular space and closely interacting NBDs. Conversion of the inward- to outward-facing conformation requires binding of MgATP, whereas subsequent ATP hydrolysis and/or product release involving one (or both) NBD resets the transporter to the ground state (the inward-facing conformation). More recently, the first crystal structures for Pgp (mouse Mdr3) have been reported that show the transporter in the inward-facing conformation (11). Interestingly, irrespective of whether drug (inhibitor) was bound or not, the overall structures were virtually identical, including a 20-Å separation of the NBDs (11).

To characterize the structure of Pgp in its natural environment, we previously generated two-dimensional crystals of the mouse and human protein reconstituted in the lipid bilayer. Electron microscopic projection structures of the two-dimensional crystals showed the two halves of the protein in close contact in projection (22). In the absence of drugs and/or nucleotides, a large cavity was observed in the center of the transporter, consistent with the 3.8-Å resolution crystal structure of detergent-solubilized apo-Pgp (11). Addition of various nucleotides with or without drug and inorganic vanadate to the two-dimensional crystals resulted in the disappearance of the central cavity and a sideways motion of the two halves of the transporter under some conditions but not others (23). However, because drugs and/or nucleotides were added after two-dimensional crystal formation, a clear correlation between substrate combination and structural changes could not be drawn.

Structural changes in Pgp were also investigated by chemical cross-linking via disulfide bonds involving naturally occurring cysteine residues in the P-loop or cysteines introduced into the signature motif by site-directed mutagenesis (24–26). In one study, disulfide bond formation is observed between the P-loop cysteines, and in another, the disulfide bonds were formed between a P-loop cysteine of one and the cysteine introduced into the signature sequence of the other NBD. In the latter study, efficiency of the cross-links was affected by the nature of the transport substrate with inhibitors resulting in little or no disulfide bond formation. It should be noted that formation of disulfide bonds under the experimental conditions employed in these studies is irreversible and that the resulting cross-linked species may represent conformations that are not found during the catalytic cycle because the cysteines used for cross-link formation are in the active site, and thus the cross-linked species is likely inactive. To investigate the movements of the NBDs during drug-stimulated ATP hydrolysis, we recently introduced cysteine residues into the C-terminal regions of the NBDs for disulfide cross-linking. The data showed that linking the C-terminal regions of the NBDs does not abolish drug-stimulated ATPase activity, suggesting that a large separation of the two NBDs at their C-terminal ends is not necessary for drug binding and ATP hydrolysis (27).

A common limitation of the available structural data is that they provide a static picture of a dynamic transport protein. To directly monitor the structural changes Pgp is undergoing during ATP hydrolysis-driven drug translocation, we designed a FRET spectroscopy-based system to monitor structural changes in real time via fluorescent dyes attached to cysteine residues introduced into equivalent regions of the N- and C-terminal NBDs using site-directed mutagenesis. For all double cysteine mutants tested, we observed that FRET efficiency increases upon addition of MgATP and transport substrate to apo-Pgp, suggesting NBD dimerization (NBD “sandwich” formation) under these conditions. Much smaller changes were seen in the presence of the nonhydrolyzable nucleotide analog ATPγS, and taken together, the data suggest that hydrolysis of ATP in at least one of the catalytic sites is required for efficient NBD sandwich formation. Further analysis of one the double cysteine mutants by single-molecule FRET spectroscopy revealed distance fluctuations in the NBDs with different dwell times. Three major conformations of catalytically active Pgp were characterized by fluctuations between high to medium and medium to low FRET efficiencies, respectively. Although drug-stimulated ATP hydrolysis populated both transitions about equally, trapping of ADP in the presence of inorganic vanadate shifted the population toward the higher FRET states, whereas in presence of the modulator cyclosporin, many molecules with low FRET efficiency transitions were observed. Dwell time analyses of the FRET states supported drug-dependent changes in NBD dynamics. The ensemble and single-molecule FRET spectroscopy data are discussed in context of the mechanism of drug-stimulated MgATP hydrolysis by Pgp.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construct Design and Site-directed Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using a cysteine-less construct of Mus musculus Mdr3 in which the seven native cysteines are changed to alanines with a six-histidine tag fused to the C terminus for affinity purification (pHILmdr3CLHis6 (28); DNA kindly provided by Gregory Tombline and Alan Senior, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed to change the following residue pairs: S375C/Q1020C, T492C/S1137C, H514C/D1159C, S586C/S1231C, and R613C/A1258C. These mutants are hereafter referred to as SQ, TS, HD, SS, and RA, respectively. Constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing (State University of New York Upstate DNA Sequencing Core Facility). The pHILmdr3His6 plasmid was then digested with NotI and transformed into Pichia pastoris using electroporation as described previously (29).

Protein Expression

Expression of cysteine-less and mutant mouse Pgp in P. pastoris was carried out essentially as described (27, 30). Briefly, 1 liter of 50% glycerol supplemented with 4.25 ml/liter Pichia trace metals (Pichia manual, Invitrogen) was fed to the inoculated fermenter over 24–48 h. Upon consumption of the glycerol, 100% methanol supplemented with 4.25 ml/liter Pichia trace metals was fed to induce expression with increasing flow rates over 36–48 h. Temperature was maintained at 29 °C. Dissolved oxygen content was monitored and maintained ≥35% with increased agitation and an oxygen feed. The pH was maintained between 4.7 and 5.0 with NH4OH. Cells were harvested with a final wet cell weight between 240 and 300 g/liter, resuspended 1:1 in mPIB (0.33 m sucrose, 0.3 m Tris/HCl, 0.05 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, pH 7.4, at 4 °C), and frozen at −80 °C in 87 g of cell/87 ml of buffer aliquots.

Protein Purification

Purification of double cysteine mutants was done as described (27, 30). All purification steps were carried out at 4 °C unless noted otherwise. 87 g of cells were thawed overnight at 4 °C. Cells were diluted by adding an equal volume of mPIB without sucrose in the presence of 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml pepstatin, and 0.5 μg/ml chymostatin. Cells were homogenized with a homemade bead beater with 0.5-mm zirconia beads (Biospec) with 12 1-min bursts, keeping the temperature of the cell suspension below 10 °C by cooling with a salt/ice mixture. After adding 1 mm fresh PMSF, the cells were then sonicated at a setting of 20 watts for 6 min in 1-min intervals on ice followed by the addition of 1 mm PMSF. The lysate was centrifuged at 3,500 × g for 15 min. The microsomal fraction was obtained by ultracentrifugation as described previously (27). Microsomes were resuspended at a protein concentration of 4 mg/ml in solubilization buffer (30% glycerol, 0.05 m NaCl, 0.05 m Tris/HCl, 0.01 m imidazole, pH 7.4) and extracted with 1.2% dodecyl maltopyranoside (DDM) in the presence of protease inhibitors. Solubilized membranes were incubated on ice for 10 min and centrifuged at 64,000 × g in a type 70Ti rotor. The supernatant was incubated for 2–4 h with co- nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose, loaded onto an AKTA FPLC with 20 column volumes of wash (0.01 m imidazole, 0.05 m NaCl, 0.05 m Tris/HCl, 30% glycerol, 0.1% DDM, 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.4), and eluted either with an imidazole gradient or directly with elution buffer (0.3 m imidazole, 0.05 m NaCl, 0.05 m Tris/HCl, 20% glycerol, 0.1% DDM, 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.4). The fractions were pooled and diluted 1:3 in DE52 buffer (0.01 m Tris/HCl, 20% glycerol, 0.1% DDM, 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.8) and applied to a 5-ml DE52 anion exchange column. The flow-through was collected, and fractions containing purified Pgp were pooled and concentrated. Protein was either used immediately after the last purification step or stored at −80 °C.

Labeling with Fluorescent Dyes for Ensemble Studies

For mutants SQ and HD, purified protein was applied to a Superdex 200 column (either 16/50 or 10/30; GE Healthcare) in labeling buffer (0.01 m MOPS/NaOH, pH 7.0, 0.05 m NaCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, 100 μm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine), 0.5% CHAPS (or 0.1% DDM for fluorescence experiments with detergent solubilized samples). Pgp-containing fractions were pooled, and protein concentration was determined by A280 with an extinction coefficient of 109,000 m−1 cm−1. Protein was incubated at 20 °C with the donor and acceptor dyes for 1 h; Alexa dyes (Molecular Probes) were used in a 2.5-fold excess, and Atto dyes (Atto-Tec) were used in a 15–16-fold excess. The reaction was quenched with 1 mm cysteine for at least 10 min at 20 °C. For samples in detergent solution, excess dye was removed with two sequential Sephadex G-50 spin columns equilibrated in labeling buffer with 0.1% DDM. Concentrations of protein and dyes were determined by absorbance for detergent-solubilized samples. For labeling of mutants TS and RA, protein was dialyzed against labeling buffer with a membrane of 3,500-Da MWCO for at least 20 h and one buffer change. Protein concentration was determined as above. The proteins were labeled with 2.5-fold excess of Alexa 488 and 21–30-fold excess of Atto 610 for 4 h at 20 °C in the dark. The labeling reaction was stopped with 1 mm cysteine for 10 min at 20 °C. Labeled protein was placed over Superdex 200 10/30 (GE Healthcare) in labeling buffer with 0.5% CHAPS. Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and Pgp-containing fractions were identified with a Typhoon Imager. Pooled fractions containing Pgp were analyzed by UV-visible spectroscopy to determine protein/donor/acceptor ratios. If necessary, labeled Pgp was concentrated using a 5,000-Da molecular mass cutoff VivaSpin concentrator.

Labeling with Fluorescent Dyes for Single Molecule Studies

Purified protein was applied to a Superdex 200 (10/30; GE Healthcare) column and eluted in labeling buffer with 0.5% CHAPS. The protein was reacted with a 2.5-fold excess of Alexa 488 and a 16-fold excess of Atto 610 for 1 h at 20 °C. Before lipid reconstitution, excess dye was quenched with 1 mm cysteine for 10 min.

Reconstitution into Proteoliposomes

A mixture of 19:1 phosphatidylcholine to phosphatidic acid (w/w) was dried under a stream of nitrogen. The dried lipid mixture was resuspended to 20 mg/ml in water, and 1-ml aliquots were frozen at −80 °C and lyophilized to remove residual solvent. The lyophilized lipids were then stored at −20 °C until use. Immediately preceding reconstitution, a 20-mg aliquot was resuspended into 0.5–1.0 ml of labeling buffer (no detergent) and sonicated with a vial tweeter until almost clear. The lipid preparation was then mixed with labeled protein in CHAPS at a 1:20 protein/lipid ratio (w/w) for ensemble studies and 1:1739 protein/lipid ratio (w/w) for single molecule observations. The protein/lipid/detergent mixture was placed over an 80-ml Sephadex G-50 column (46 × 1.5 cm) at room temperature, and 1-ml fractions were collected. Dye concentrations were determined by visible absorbance in the presence of 2% CHAPS. Samples were either used immediately or stored in aliquots at −80 °C.

Ensemble Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Fluorescence spectroscopy experiments were carried out in a FluoroLog3-21 spectrofluorometer (HORIBA Jobin Yvon) in a 3 × 3-mm quartz cuvette. Temperature was maintained at 37 °C. Excitation and emission slit settings were between 2 and 3 nm. Excitation for Alexa 488 was 493 nm and for Atto as follows: Atto 610, 615 nm; Atto 565, 563 nm; and Atto 655, 663 nm. Emission was recorded at each wavelength with 0.5-s integration time. Spectra were corrected for dilution factors. Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min before a 5-min incubation in the cuvette, which was maintained at 37 °C. Three emission scans were collected in the apo condition. Substrate was then added to the cuvette (200 μm verapamil (3.2 μl) or 5 mm MgSO4, 1 mm ATP (3.2 μl)) and incubated for 5 min, and three individual emission spectra were recorded. The second substrate was then added and recorded similarly. Multiple spectra were recorded for each condition, sequentially, to compose a set. After addition of 10 μm sodium orthovanadate, sequential emission scans were collected over a period of ∼20 min until the spectral changes were minimal between scans (the final emission scan was used for analysis). Mixing was executed by hand. Each set of each condition was averaged. At least two individual sets of experiments were completed. Experiments were not combined for averaging to prevent additional error from combining two independent sets of data.

Data Analysis

The donor emission peak intensity, an average of the peak intensity over 3 nm, in counts/s (cps) was divided by the acceptor emission peak intensity, an average of the peak intensity over 3 nm in cps, to give the donor to acceptor ratio (D/A). Standard deviation was calculated for each condition, except for the vanadate-trapped data point (only the final scan after addition of vanadate was used). For comparison of data from different experiments, the D/A ratio for each experiment was normalized to the D/A ratio of the apo condition.

Single Molecule FRET

Samples were thawed at 4 °C, applied to a 1-ml Sephadex G-50 spin column equilibrated in 10 mm MOPS, 50 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2 pH 7.0, and diluted as necessary in buffer to obtain a maximum of one proteoliposome at any time in the confocal volume. Samples were then incubated for 5 min at 37 °C with the conditions as follows: “apo,” 5 mm MgCl2, no substrate; “verapamil transport,” 5 mm MgSO4, 1 mm ATP, 200 μm verapamil; “vanadate-trapped,” 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP, 200 μm verapamil, 237 μm sodium orthovanadate; “cyclosporin transport,” 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP, 5 μm cyclosporin A.

The home-built microscope with expanded confocal detection volume of about 10 fl was described previously (31, 32). Two lasers in duty cycle-optimized alternating fashion were used to excite the donor and acceptor (33). Briefly, the donor was excited with a blue pulsed laser (PicoTa 490, up to 80 MHz repetition rate, Picoquant) at 488 nm with 150 microwatts. The acceptor was excited with an orange continuous HeNe laser at 594 nm with 30 microwatts, switched by an acousto-optical modulator. The alternating laser sequence was set for four blue laser pulses at a 16-ns interval with a 60-ps pulse duration followed by a single 32-ns pulse of the orange laser 16 ns after the fourth blue pulse. Photons were detected by two avalanche photo diodes and detected between 497 and 567 nm (HQ 532/70, Advanced Harmonic Filter) for Alexa 488 and wavelengths longer than 595 nm for Atto 610 (LP 595, AHF). Recording of the photons with picosecond time resolution was achieved by synchronized TCSPC electronics (SPC 153, Becker & Hickl) in a computer for subsequent fluorescence lifetime analysis, fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, and FRET analysis.

Single Molecule Analysis

Bursts were automatically marked based on fluorescence intensity thresholds using the software Burst-Analyzer by N. Zarrabi (34, 35). Briefly, photon bursts had to exceed 20 counts per ms (cpms) in the acceptor channel when directly excited with 594 nm, as well as 10 cpms in the FRET donor channel and 10 cpms in the FRET acceptor channel upon 488 nm excitation. The duration of a burst was allowed to be in the range between 20 and 1,000 ms related to the mean diffusion time of 30 ms for the proteoliposomes. Background corrections of 11 and 5 cpms were subtracted for the FRET donor and acceptor intensities, respectively. FRET states within the photon bursts were identified manually. Each biochemical condition was compiled in a data file for further analysis using a series of MATLAB scripts to obtain FRET efficiency histograms, FRET transition density plots, and dwell time distributions.

RESULTS

Site-directed Mutagenesis

To address domain movement in Pgp using FRET spectroscopy, pairs of cysteines were placed at equivalent positions in the N- and C-terminal nucleotide binding domains of the transporter for covalent labeling with maleimide-linked fluorescent dyes. Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out with a cysteine-less version of Pgp (mouse Mdr3) that had previously been shown to exhibit near wild type levels of drug-stimulated ATPase activity (28). For structure-based placement of cysteine residues, we modeled the N- and C-terminal NBDs of Pgp using the crystal structure of MgADP-bound Sav1866 (36) as a template3 (Fig. 1). The locations of the cysteine pairs were chosen to get a sampling of the various subdomains of the NBDs in terms of distance from the membrane and across the putative NBD dimer interface. A further criterion for the chosen locations was to be able to detect both translation (y axis in Fig. 1A) and opening-closing (x axis) motion of the NBDs, motions predicted from a comparison of available crystal structures of ABC transporters adopting inward- and outward-facing conformations.

FIGURE 1.

Placement of cysteine mutants in the structural models of Pgp. A, residue placement in the crystal structure of Pgp in the apo-form (Protein Data Bank code 3g5u (11)) looking from the cytosol toward the membrane (top) and parallel to the membrane (bottom). B, same views as in A for the Pgp NBD homology model generated with Sav1866 (Protein Data Bank code 2hyd (36)) as template. The transmembrane domains were not modeled due to the low similarity between Pgp and Sav1866 in this region of the proteins. Residue locations for introducing cysteines were chosen that were not highly conserved and not part of secondary structure. Mutant pairs are S375C/Q1020C (SQ, black), T492C/S1137C (TS, yellow), H514C/D1159C (HD, pink), S586C/S1231C (SS, green), and R613C/A1258C (RA, cyan). Mutant SS, chosen before the release of the Sav1866 structure, could not be purified. C, predicted Cα distances between cysteines introduced by site-directed mutagenesis using the Pgp apo and homology model of the NBDs.

Protein Purification, Maleimide Labeling, and Reconstitution

Based on immunoblots, all five double cysteine mutants were expressed in P. pastoris following induction with methanol (data not shown). Although mutant SS was rapidly degraded upon extraction from the membrane, mutants TS, HD, RA, and SQ were stably expressed and could be purified according to established protocols. The typical yield was 3–4 mg of purified Pgp per 87 g of cells. Fig. 2A shows SDS-PAGE of purified mutant TS. Similar results were obtained for mutants SQ, HD, and RA (data not shown). Typical values for verapamil-stimulated specific ATPase activities for Cys-less (CL), TS, RA, SQ, and HD Pgp were 1.7, 2.1, 2.0, 1.3, and 2.2 μmol/(min·mg), respectively, close to published values for wild type and Cys-less Pgp expressed in P. pastoris (28).

FIGURE 2.

Protein purification, labeling, and reconstitution. A, Coomassie-stained 10% polyacrylamide gel. Lane 1, molecular weight marker; lane 2, 2.6 μg of purified mutant TS. Similar yields and purity were obtained for SQ, RA, and HD mutants (data not shown). B, SDS-PAGE of labeled HD proteoliposome fractions from Sephadex G-50 column, imaged with a fluorescence scanner at wavelengths for Alexa 488 (top) and Atto 610 (bottom). Lane 1, molecular weight marker, lanes 2–6, fractions 13–17. C, negative stain transmission electron microscopic image of labeled mutant SQ reconstituted into proteoliposomes.

Mutant proteins were labeled with donor and acceptor dyes selected based on the predicted distances of the two cysteines in the Pgp homology model of the outward facing conformation as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Dyes that stimulated Pgp ATPase activity in a manner seen for transport substrates, and/or bound nonspecifically to cysteine-less Pgp (e.g. Alexa Fluor 546), were not used for FRET experiments. Several labeling schemes were tested, including substoichiometric labeling with one dye followed by labeling with an excess of the second dye or labeling with mixtures of the dyes in a predetermined ratio, either before or after concentrating the protein. Most reproducible results were obtained by labeling dilute protein in the presence of 0.1% DDM with subsequent removal of excess dye and exchange of DDM by 0.5% CHAPS (for liposome reconstitution by size exclusion chromatography).

Labeled Pgp mutant proteins were reconstituted into proteoliposomes (phosphatidylcholine/phosphatidic acid 19:1) using gel filtration as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Turbid fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the presence of donor and acceptor fluorescent dyes in the proteoliposome-containing fractions was verified on a fluorescence scanner (Fig. 2B). The average size of the proteoliposomes as determined by negative stain transmission electron microscopy was around 50–150 nm (Fig. 2C). Labeling efficiency and donor/acceptor stoichiometry was determined by UV-visible spectroscopy. For mutants RA and TS, protein and dye concentrations were determined after excess dye was removed by Superdex 200 gel filtration, before liposome reconstitution. For mutants HD and SQ, dye concentrations were measured after liposome reconstitution. For these samples, protein concentration could not be determined reliably due to interference of the CHAPS used to solubilize the liposomes before UV-visible spectroscopy. The concentrations of the samples used in these experiments were as follows: RA, 4.1 μm protein, 1.98 μm Alexa 488, 5.02 μm Atto 610; TS, 2.35 μm protein, 0.31 μm Alexa 488, 0.59 μm Atto 610; HD 0.25 μm Alexa 488, 0.33 μm Atto 610; SQ, 0.34 μm Atto 565, 0.10 μm Atto 655. Column fractions containing liposome-reconstituted, double-labeled protein were pooled and used for fluorescence spectroscopy.

FRET Spectroscopy of Reconstituted Pgp

FRET spectroscopy was carried out to investigate the conformational changes that occur in response to drugs (verapamil), nucleotide, and vanadate as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The dyes used for each mutant, excitation wavelength, and excitation and emission slit widths are summarized in Table 1. Fig. 3 shows FRET spectra obtained for bilayer reconstituted mutant TS labeled with Alexa 488 (donor) and Atto 610 (acceptor), normalized to the apo-donor peak for comparison. Comparing the donor to acceptor (D/A) ratio between the spectra is an established method of estimating relative distance changes between two fluorophores (37–39). An increase in D/A ratio would indicate a decrease in FRET efficiency and an increase in the distance between the donor and acceptor molecules. A decrease in D/A ratio would indicate a decrease in distance. As can be seen, addition of the ATPase stimulator verapamil (Fig. 3, green trace) to liposome-bound apo-Pgp (blue trace) does not lead to a significant decrease of the D/A fluorescence ratio, suggesting that binding of the drug alone does not induce a conformational change in the NBDs. A more significant decrease of the D/A ratio (∼12%) is observed upon addition of MgATP (Fig. 3, red trace), suggesting that verapamil-stimulated hydrolysis of MgATP increases the population of molecules with closely interacting NBDs.

TABLE 1.

Parameters for ensemble fluorescence spectroscopy data collection

| Mutant | Donor | Acceptor | Excitation slit | Emission slit | Excitation wavelength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | nm | nm | |||

| SQ | Atto 565 | Atto 655 | 3 | 3 | 563 |

| TS | Alexa 488 | Atto 610 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 493 |

| RA | Alexa 488 | Atto 610 | 2 | 2 | 493 |

| HD | Alexa 488 | Atto 610 | 2–2.5 | 2–2.5 | 493 |

FIGURE 3.

Fluorescence spectroscopy of reconstituted mutant TS. Shown are fluorescence spectra from one experiment with TS proteoliposomes, labeled with Alexa 488 and Atto 610. All spectra are taken at 37 °C. Excitation wavelength is 493 nm. Three sequential spectra are recorded for each condition. After the apo-spectra were collected, 200 μm verapamil was added, and the cuvette was incubated for at least 5 min; three sequential fluorescence wavelength scans from 503 to 730 nm were then recorded. The same sequence was repeated after addition of 1 mm MgATP. After that, 10 μm sodium orthovanadate was added, and wavelength scans were recorded until emission was stabilized. Each trace is representative of at least three emission scans averaged, except the condition for vanadate where the last scan is shown. For ease of viewing, the spectra have been normalized to the donor peak recorded for the apo condition.

In control experiments using a mixture of free dyes (see supplemental material), we found that excitation of the donor dye (Alexa 488) did not produce significant acceptor (Atto 610) fluorescence at similar dye concentrations as present in the protein samples. The observed acceptor fluorescence in double-labeled Pgp must therefore be due to energy transfer from the donor dye. Pgp molecules with one or two donor dyes only (no acceptor) will produce donor fluorescence signal along with the donor fluorescence from Pgp molecules having both donor and acceptor bound. The excess donor fluorescence will result in a larger D/A ratio than would be expected from uniformly donor- and acceptor-labeled Pgp. An overall increase in D/A ratio due to excess donor labeling will therefore only “dilute” the observable change in the D/A ratio but not change its direction. Pgp molecules having two acceptor dyes bound will not contribute to the signal in any way and will thus be invisible in the experiment.

Vanadate Trapping

Vanadate has been shown to inhibit drug-stimulated ATPase activity of Pgp by trapping ADP at one catalytic site (presumably in the “nucleotide sandwich” conformation) (20). Thus, vanadate trapping was carried out as described under “Experimental Procedures” to investigate changes in FRET efficiency upon inducing this transition state conformation. As can be seen, addition of 10 μm sodium orthovanadate (Fig. 3, black trace) resulted in a final overall drop of the D/A ratio of ∼20%. The decrease of the D/A ratio was time-dependent with stable fluorescence emission reached after about 15–20 min after addition of vanadate.

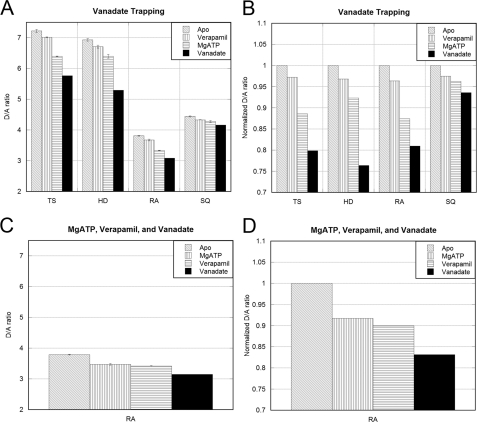

Similar experiments as the ones described above for mutant TS were carried out for mutants HD, RA, and SQ, and the substrate-dependent changes in D/A fluorescence for all four mutants tested are summarized in Fig. 4. Spectra for SQ, HD, and RA displayed an overall similar appearance with varying D/A fluorescence intensity ratios and changes in the ratio upon addition of drugs and/or nucleotides. As can be seen from the barographs in Fig. 4, mutant HD shows the overall largest decrease in D/A ratio upon vanadate inhibition (∼24%), closely followed by TS (∼20%) and RA (∼19%). The smallest change (∼6%) is seen for mutant SQ, consistent with the prediction form the comparison of apo- and ADP-bound structures shown in Fig. 1.

FIGURE 4.

D/A ratios of vanadate-trapped Pgp. A, comparison of the D/A fluorescence emission ratios in response to verapamil, MgATP, and vanadate. Verapamil (200 μm) and MgATP (1 mm) traces are averages of a minimum of three scans, whereas the D/A ratio for vanadate (10 μm) is from the final scan of the experiment. B, normalized D/A ratios from A. The D/A ratio of each mutant in the apo condition was used to normalize the D/A ratio of the substrate conditions. C, using mutant RA, addition of 1 mm MgATP was followed by 200 μm verapamil and then 10 μm vanadate to test whether the order of adding drug or nucleotide had an influence on the final D/A ratio. D, normalized D/A ratio of RA as in B.

To test if the magnitude of the overall FRET efficiency change is a function of the order of substrate addition, we performed experiments in which MgATP was added first followed by verapamil. The result is shown in Fig. 4, C and D, for mutant RA. As can be seen, the D/A ratio of RA decreased by 17% when MgATP was added before verapamil compared with a 19% decrease when verapamil was added first (followed by vanadate trapping under both conditions).

Although the changes in D/A ratios for the different mutants are not necessarily comparable on a quantitative level due to the aforementioned differences in labeling ratios and efficiencies, the observation that the overall D/A ratio changes are similar and independent of the order of addition of drug and MgATP suggests that the resulting steady state is likely the same.

MgATPγS and Verapamil

Previously, it had been shown that the magnesium-bound form of the nonhydrolyzable ATP analog, ATPγS, binds Pgp with higher affinity compared with MgATP (16, 18, 20). We therefore investigated whether binding of MgATPγS would lead to a similar decrease in D/A ratio as MgATP. Observation of a similar change in FRET efficiency upon MgATPγS binding would indicate that the nonhydrolyzable ATP analog was able to induce NBD sandwich formation. As is seen in Fig. 5, the addition of 200 μm verapamil followed by 5 mm MgSO4 and 1 mm ATPγS yielded only minor changes in the D/A ratio, independent of whether verapamil or MgATPγS was added first. Generally, there is even less change in the overall D/A ratio when MgATPγS is present before addition of verapamil. Using HD as an example, the normalized D/A ratio when adding verapamil first decreases by 2% followed by essentially no change with the addition of MgATPγS. However, when MgATPγS is added to HD followed by verapamil, the D/A increases by 1% followed by a 3% decrease. Details of all mutants in the presence of MgATPγS and verapamil are shown in Fig. 5. Overall, the MgATPγS binding experiments seem to suggest that binding of the nonhydrolyzable ATP analog does not produce a significant population of Pgp molecules with closed NBDs. This result is surprising considering the higher affinity of MgATPγS compared with MgATP (16, 18, 20). It is possible that MgATPγS was not able to induce the occluded state under the conditions of the FRET experiment, but it cannot be ruled out that MgATPγS binds differently compared with MgATP.

FIGURE 5.

Substrate-induced changes in donor to acceptor ratio. A, comparison of the ratio of donor to acceptor emissions in response to addition of 200 μm verapamil, followed by 1 mm MgATPγS (5 mm MgSO4, 1 mm ATPγS). B, D/A ratio for each mutant was normalized to the apo condition. B is the normalized D/A ratio for A. C, comparison of the donor to acceptor emission in response to MgATPγS followed by verapamil (concentrations as in A). D, normalized D/A ratios as in B for C.

Single-molecule FRET

The ensemble FRET experiments described above suggest that in presence of verapamil and MgATP, the two NBDs (as observed by way of the attached dye molecules) get on average closer to each other (and even more so in presence of vanadate). However, due to the nature of the ensemble experiments, it is not possible to distinguish between a situation where all the molecules have semi-closed NBDs or where subpopulations of molecules exist at any given time that either have tightly associated, semi-open, or completely open NBDs, a situation as could be expected for active turnover. To overcome the limitation of ensemble FRET, we therefore decided to employ single-molecule FRET spectroscopy to further analyze the conformational changes associated with drug-stimulated ATP hydrolysis. Using mutant TS stochastically labeled with Alexa 488 and Atto 610, fluorescence was recorded from single Pgp molecules reconstituted into liposomes using a confocal single-molecule FRET (smFRET) setup as described (33). In the smFRET setup, proteoliposomes diffuse freely through a confocal excitation volume of about 10 fl (calculated by fitting the autocorrelation function of rhodamine 110 in buffer for FCS analysis). Two pulsed lasers were focused on the confocal volume in a droplet of proteoliposomes containing buffer to either excite Alexa 488 for the FRET measurement or Atto 610 to verify the existence of both fluorophores at one protein, respectively, in an optimized interleaved excitation scheme (40, 41). Photon counts were binned to 1-ms intervals. The resulting time trajectories exhibited bursts of photons indicating that a double-labeled Pgp had traversed the confocal volume. The lasers generated also some background of scattered light. Background corrections between 11 cpms for Alexa 488 and 5 cpms for Atto 610 were subtracted. The proximity factor P was calculated per data point in the time trace by Equation 1,

with IA and ID intensity of the acceptor and donor, respectively. To determine FRET efficiencies, the γ correction factor accounting for detection efficiencies of the instruments and quantum yields of the donor and acceptor was calculated. Using quantum yields of 0.6 and 0.7 for Alexa 488 and Atto 610, respectively, the γ correction factor was calculated to be 0.79 (quantum yields as given by the supplier of the dyes).

FRET efficiencies were calculated by Equation 2,

A total of four conditions was tested in the smFRET spectroscopy setup as follows: (i) apo (5 mm MgCl2 in the buffer but no nucleotide or drug added); (ii) verapamil transport (1 mm MgATP + 200 μm verapamil); (iii) vanadate-trapped (1 mm MgATP + 200 μm verapamil + 237 μm orthovanadate); and (iv) cyclosporin transport (1 mm MgATP + 5 μm cyclosporin A). Here, 1 mm MgATP refers to 5 mm MgCl2 (already present in the buffer) plus 1 mm ATP. Although considered a transport substrate, cyclosporin A has been shown to activate Pgp ATPase barely above basal levels (27). We therefore included the cyclosporin transport condition with the expectation that the steps of the catalytic cycle that are slowed down compared with verapamil, for example, would be noticeable in the single molecule measurements. For each condition, several time traces of 10 min each were collected. Photon bursts were automatically identified using threshold criteria in the software “Burst-Analyzer” (34, 35), followed by manually screening for artifacts and verifying the presence of both donor and acceptor dyes. Individual FRET steps, i.e. distinguishable different levels of proximity factors or FRET efficiencies, were marked within each burst manually. Photon bursts with marked steps were then analyzed with MATLAB scripts to generate FRET efficiency histograms, FRET 1–2 transition density plots and dwell time distributions.

Photon bursts of single Pgp for different biochemical conditions are shown in Fig. 6. In the lower panels of Fig. 6, the fluorescence intensities of FRET donor (green trace) and acceptor (red trace) with 1-ms binning are depicted. In the upper trace of Fig. 6, the corresponding fluorophore-fluorophore distances are plotted based on photon probabilities using the software “FRET-TRACE” (42). MgATP-driven transport of verapamil (Fig. 6, A–C) resulted in relative intensity changes of FRET donor and acceptor within a photon burst. To ensure that both fluorophores were attached, a third fluorescence intensity trace was recorded using direct excitation of the acceptor with 594 nm (see supplemental Fig. S1). To illustrate the process of single-molecule FRET data analysis, we will discuss Fig. 6A briefly. At about 25 ms, both fluorescence intensities increased above the thresholds indicating that the FRET-labeled Pgp had entered the confocal detection volume. This photon burst ended at about 190 ms because the transporter was leaving the confocal volume, and the intensities drop below the threshold. Within this photon burst at about 35 ms, the FRET distance increased from 6.0 to 6.5 nm but switched back after about 20 ms. At about 90 ms, the distance increased again to 6.5 nm, followed by a decrease to 5.5 nm for 20 ms. At 125 ms, the fluorophore distance increased to 6.0 nm and switched back to 5.5 nm after 10 ms. Around 150 ms, the distance decreased even further. Manual assignment of FRET levels in this burst based on the proximity factor trace is shown in the supplemental Fig. S1. The other two photon bursts (Fig. 6, B and C) showed also strong fluctuations of the FRET distances during MgATP-driven transport conditions.

FIGURE 6.

Example bursts from smFRET spectroscopy for mutant TS. A–C are for condition verapamil transport (1 mm ATP, 5 mm MgCl2, and 200 μm verapamil). D–F are for conditions apo (no substrate, 5 mm MgCl2 in the buffer), vanadate-trapped (1 mm ATP, 5 mm MgCl2, 200 μm verapamil, and 237 μm vanadate), and cyclosporin transport (1 mm ATP, 5 mm MgCl2, and 5 μm cyclosporin A), respectively. For details, see text.

In contrast, bursts for the apo condition (Fig. 6D) exhibited a nearly constant large distance between 6.5 and 7 nm throughout the observation time. In the presence of vanadate (vanadate-trapped condition), the FRET distances within a photon burst fluctuated mostly around lower distances between 5.0 and 5.5 nm, as seen in Fig. 6E. In the presence of MgATP and cyclosporin A (cyclosporin transport), similar FRET distances changes were observed as in the case of MgATP-driven verapamil transport. The photon burst in Fig. 6F illustrates the large changes of the fluorophore distances between 4.5 and 6 nm with slower transition for the shorter distances.

Of the 80 bursts analyzed for the apo condition, 55% showed a constant FRET efficiency and 37% three and more distinguishable FRET levels. In contrast, for verapamil transport, 74% of the 216 bursts analyzed exhibited three and more FRET levels with only 7% of the bursts with constant FRET distances. For the vanadate-trapped, 16% of 249 burst remained in a constant FRET level, with 61% fluctuating between three and more levels. For cyclosporin transport, 33% from 224 bursts showed one constant FRET level and 38% exhibited three and more FRET levels.

To analyze the observed distance distributions, the assigned FRET efficiency levels were plotted in histograms. Fig. 7 shows FRET efficiency histograms (with corresponding FRET distances as the upper axis in the panel) for the four conditions tested for mutant TS. As can be seen in the apo condition, FRET efficiencies varied from 0.18 to 0.72 centered near 0.5. In the verapamil transport condition, the FRET efficiencies ranged from 0.22 to 0.88 with the center near 0.6. For vanadate-trapped, FRET efficiencies ranged from 0.18 to 0.88 with the center shifting to near 0.7. Under the cyclosporin transport condition, sampled FRET efficiencies ranged from 0.22 to 0.82 centered near 0.5.

FIGURE 7.

Single molecule histograms for mutant TS. The FRET efficiencies of single molecule trajectories of mutant TS are shown. The conditions are as follows. A, apo (5 mm MgCl2 in the buffer); B, verapamil transport (1 mm ATP, 5 mm MgCl2, and 200 μm verapamil); C, vanadate-trapped (1 mm ATP, 5 mm MgSO4, 200 μm verapamil, and 237 μm vanadate); and D, cyclosporin transport (1 mm ATP, 5 mm MgCl2, and 5 μm cyclosporin A).

A transition from one FRET efficiency to another FRET efficiency within a burst, or a step to step, gives information regarding the conformational changes sampled by the fluorescence burst. This is displayed by plotting FRET distance 1 in a burst against the subsequent FRET distance 2 in the same burst (Fig. 8). The FRET 1–2 transition plot for condition apo revealed only few transitions (out of 119 FRET levels), mostly in the 5.5- to 6.5-nm range, because most photon bursts did not show the required distance changes between at least four FRET levels (see above). A different picture was obtained for verapamil transport, with two dominating transitions between 5.0 and 5.5 nm and back, as well as between 6.0 and 5.5 nm and back. However, also transitions at larger distances as well as shorter distances were observed within 809 FRET levels. Under conditions of vanadate trapping, only the transitions between 5.0 and 5.5 nm were densely populated (based on 621 FRET levels), consistent with the ensemble experiments that showed the highest mean FRET efficiency for this condition. Conversely, the condition cyclosporin transport appeared to shift the population to several transitions, one at higher FRET efficiency centered at 4.8 nm (that is present but barely detected under condition verapamil transport), one around intermediate efficiency (5.0 to 5.5 nm), and one at a lower efficiency FRET centered on 6 nm (367 FRET levels in total). Cyclosporin A is one of the larger transport substrates that barely activates ATP hydrolysis above basal levels in biochemical ensemble measurements, and it is possible that conformations that are too short lived to be observed in significant numbers under condition verapamil transport were stabilized with cyclosporin A bound.

FIGURE 8.

FRET transition plots for mutant TS. After marking bursts and steps within the bursts, FRET transition plots were created by calculating the first FRET level of the burst (x axis) and plotting that distance against the second FRET level (y axis). If there were more than two FRET levels in each burst, then level two was plotted against level three, etc. The panels follow the same layout as Fig. 7.

Furthermore, information about how long the molecule spends in each level or conformational state can be gained by examining the dwell times. This is shown in Fig. 9. The longer the dwell time, the longer the molecule stays in one conformation with no change in FRET efficiency. Therefore, photon bursts had to show at least three FRET levels, because only the intermediate dwell could be used for the dwell time distribution. The length of the first and the last FRET level in a burst remains unknown because they were limited by entering or leaving the confocal detection volume. In the apo condition, the average dwell time was ∼36 ms using a mono-exponential decay fitting. Under condition verapamil transport, the dwell time was reduced significantly to around 7.4 ms, although under condition vanadate-trapped, the average life time was prolonged and close to 35 ms. Finally, under conditions of cyclosporin transport, the dwell time was close to 10 ms similar to the transport condition in presence of verapamil.

FIGURE 9.

Dwell time histograms for mutant TS. After marking bursts and steps within the bursts, the first and last step of each burst was discarded since the amount of time the protein had been in that level before entry into the confocal volume and remains in the final level after exiting the confocal volume is unknown. The duration that Pgp spent in each “middle” level was then recorded and plotted to give the dwell time. The panels follow the same layout as Figs. 7 and 8.

Taken together, the smFRET data show that condition apo is characterized by low FRET efficiencies and long dwell times with few observed transitions in the FRET 1–2 plot. At least three major conformations are observed under conditions of verapamil transport with a much shorter dwell time of 7 to 8 ms. Vanadate trapping shifts the population to transitions at higher FRET efficiencies with slower transitions, although cyclosporin transport populates high, intermediate, and low FRET efficiencies with shorter dwell times.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we have studied the structure- and ligand-induced structural changes of the lipid bilayer-bound Pgp by transmission electron microscopy of two-dimensional crystals (22, 23). The data showed that although apo-Pgp displayed a large central cavity in projection, addition of nucleotide and/or drug resulted in projections in which the two halves of the transporter appeared to interact more closely, thereby closing the central cavity. However, because of the limited resolution of the projection data and the static nature of the protein in the two-dimensional crystals, questions remained as to the order and magnitude of the structural changes induced by addition of drugs and nucleotides. Consistent with the EM data, a large central cavity is also seen in the recent crystal structure of apo- and drug-bound Pgp (11); however, a high resolution structure of nucleotide-bound Pgp that would provide insight into how the NBDs are interacting upon nucleotide binding is currently not available. However, there is now ample evidence that the catalytic cycle of Pgp includes formation of a so-called ATP sandwich conformation characterized by dimerization of the N- and C-terminal NBDs with nucleotide sandwiched by the P-loop of one and the ABC signature motif of another NBD. Such a nucleotide sandwich configuration can be seen in a variety of x-ray crystal structures of either isolated NBDs (43, 44) or intact bacterial ABC transporters (36, 45, 46), and these structures have provided a detailed picture of the interface in the symmetric NBD-NBD dimer.

What is currently not known with certainty is how much the NBDs have to come apart (dissociate) during the catalytic cycle to allow release of inorganic phosphate (Pi) and exchange of ADP with ATP as well as opening of the cytoplasmic drug binding pocket. Considering the recent crystal structure of apo-Pgp that shows the NBDs separated by up to 30 Å, the authors of that study suggested that the NBDs will likely have to come apart during catalysis to allow for binding of especially bulky drug molecules (11).

From studies with mutant Pgp or vanadate-trapping experiments, it is well established that the two catalytic sites in Pgp act in a cooperative fashion in that inactivating one catalytic site by mutation or vanadate binding abolishes drug-stimulated ATPase activity (15, 47). Furthermore, it has been shown that nucleotide can be trapped in catalytic sites given that hydrolysis cannot proceed because essential residues involved in catalysis have been mutated (47), or by using a nonhydrolyzable nucleotide analog such as ATPγS (16, 17, 20), or by replacing phosphate with e.g. orthovanadate or beryllium fluoride to stabilize the ADP-bound post- or prehydrolysis state (20, 48). Taken together, the mutagenesis and nucleotide-trapping experiments suggest that drug-stimulated ATP hydrolysis in Pgp occurs in an alternating fashion with the NBDs staying associated for at least two hydrolysis events (18).

In this study, we have designed a system in which structural changes involving the NBDs are detected in real time using double cysteine mutants labeled with donor and acceptor fluorescent dyes for FRET spectroscopy using bulk samples as well as single molecules. FRET spectroscopy is a powerful tool for studying relative distance changes in biological macromolecules, and the technique has previously been applied to estimate distances and distance changes in Pgp using fluorescently labeled lipid molecules and nucleotide analogs (49–51). We used a combination of secondary structure prediction and homology modeling to identify pairs of residues in the two NBDs that were predicted to undergo large distance changes when going from an outward-facing (such as seen in the ADP-bound structure of Sav1866 (36)) to the inward-facing conformation (such as seen in the recent crystal structure of mouse Pgp (11)). Site-directed mutagenesis was conducted using a Cys-less background of mouse Pgp (Mdr3), and four of the five mutants that were generated could be expressed in P. pastoris and purified to homogeneity (double mutant S586C/S1231C was expressed but could not be purified due to rapid degradation). For the four mutant proteins that could be purified, the introduced cysteines did not compromise the drug-stimulated ATPase activity compared with the Cys-less Pgp background (see “Results”). Mutants, SQ, TS, HD, and RA were subsequently used in FRET spectroscopy.

In the first part, we analyzed FRET efficiency changes in bulk samples as a function of nucleotide and drug binding. Generally, the overall magnitude of the FRET signal depends on the distance of donor and acceptor dyes but also a number of other factors, including how close the actual distance is to the optimum distance for the dye pair used (R0) as well as the labeling efficiencies, fluorescence lifetimes, and quantum yields. The measured FRET efficiency of bulk samples will also depend on the amplitudes of the various catalytic intermediates under turnover conditions: in other words, what fraction of one catalytic cycle the NBDs of Pgp spend in close association (in the ATP sandwich), partly dissociated association (during Pi/ADP release), or fully dissociated association (as in the crystal structure of apo-Pgp). For example, if the NBD dimer (or ATP sandwich) is only a transient intermediate (short lived), its amplitude during steady state ATP hydrolysis will be small. If, however, the ATP hydrolysis reaction is the rate-limiting step, the ATP sandwich will be the predominant species.

Starting with lipid bilayer-reconstituted apo-Pgp, we showed that addition of drug alone resulted in only a small (2–3%) decrease of the D/A ratio, consistent with the recent crystal structures of Pgp, which showed the same separation of the NBDs in the apo- and drug-bound models (11). A larger increase in FRET efficiency, however, was seen upon addition of MgATP, consistent with a decrease of the average distance separating the donor and acceptor dyes as would be expected for NBD dimer formation. Although the absolute changes in D/A ratio for the different mutants cannot be compared in a straightforward manner because of the above-mentioned variables, the observation that mutant SQ produced the smallest increase in FRET efficiency is consistent with the predicted distance change for this residue pair when going from inward- to outward-facing conformations as shown in Fig. 1. It should also be noted that irrespective of whether verapamil or MgATP was added first, the final D/A ratio was approximately the same (as shown for mutant RA in Fig. 4), suggesting that binding of drug and nucleotides are independent and additive events.

It is known that inorganic vanadate traps ADP in one catalytic site with concomitant loss of ATPase activity (20). Furthermore, it has been postulated that the vanadate-inhibited state requires NBD dimerization so that one catalytic site can be closed (52). For all four mutants, we observed a further decrease of the D/A ratio upon addition of orthovanadate (most pronounced for HD followed by TS and RA). This increase in FRET efficiency upon vanadate inhibition could be either due to a further decrease of the NBD-NBD distance (with approximately constant amplitude of the NBD dimer intermediate) or an increase of the population of Pgp molecules with closely associated NBDs (compared with the state of drug-stimulated ATP hydrolysis before vanadate inhibition). Considering the smFRET analysis discussed below, it appears that the latter possibility is the more likely explanation.

Previous reports using MgATPγS showed that the nonhydrolyzable ATP analog binds Pgp with significantly higher affinity compared with MgATP (16, 18, 20). Furthermore, it has recently been shown that MgATPγS can be trapped in one catalytic site, and much like with vanadate trapping, it has been assumed that the resulting “nucleotide occluded state” requires closing of one of the two catalytic sites, although the other site is open and can exchange nucleotide freely (16, 18). It was therefore surprising to see that addition of MgATPγS to doubly labeled Pgp did not result in a significant increase in FRET efficiency beyond the small increase seen with verapamil, irrespective of which mutant was used and in which order nucleotide and drug were added. Interestingly, when adding MgATPγS followed by MgATP (or vice versa), the same FRET efficiency change was observed as with MgATP alone (data not shown). There are conflicting reports whether ATPγS is turned over by Pgp and whether at least one turnover is required for reaching the occluded state (16, 18). Given that at least one turnover is required, it is possible that under the conditions of the FRET spectroscopy experiment no turnover and therefore no ATPγS occlusion occurred. However, because there is currently no high resolution structure showing that the MgATPγS-occluded state resembles the ATP sandwich, it cannot be ruled out that the nonhydrolyzable ATP analog is bound in a configuration that is different compared with the e.g. ADP-Vi-trapped state. This finding would be consistent with EM projections that showed ADP-Vi-trapped Pgp without a central cavity (outward facing) in contrast to MgATPγS-bound Pgp that had a central cavity between the two halves similar to the apo-form of the transporter (23).

In summary, we have shown that FRET spectroscopy can be applied to obtain information regarding the motions the NBDs are undergoing upon binding of substrates starting from the apo-form of the transporter. However, in the so-far described ensemble FRET, catalytic turnover of the Pgp molecules is not synchronized, which means that, as mentioned above, an average distance of the dye molecules is measured, and that the magnitude of the FRET change will not only depend on the distance between the dye molecules but also on lifetimes and amplitudes of the reaction intermediates.

To extend the information obtained from analyzing bulk samples by ensemble FRET, we have monitored real time conformational changes in one mutant, TS, by single-molecule FRET spectroscopy. Mutant TS was diluted and reconstituted into lipid vesicles at a high lipid/protein ratio to ensure that each liposome contained on average less than one double-labeled transporter. Four conditions were tested by single-molecule FRET as follows: (i) apo (no nucleotide or drug added); (ii) verapamil transport (MgATP plus verapamil); (iii) vanadate-trapped (MgATP plus verapamil plus orthovanadate); and (iv) cyclosporin transport (MgATP plus cyclosporin A). For each condition, a similar number of fluorescence photon bursts was collected. However, only relatively few transitions for the apo condition could be included in the statistics because of the large fraction of Pgp transporters that remained in a stable nonfluctuating conformation according to the FRET signal under this condition. The observed low FRET efficiencies are likely due to the large distance of the dye molecules (bound to the NBDs) in the apo condition, consistent with the ensemble FRET experiments where the lowest mean FRET efficiency was observed for apo-Pgp. Despite the differences in the number of observations, all four conditions show a relatively broad distribution in the FRET efficiency histograms, indicating that Pgp is a highly dynamic protein that is constantly sampling a range of NBD conformations. As expected from the ensemble measurements, the average FRET efficiency increased in conditions verapamil transport and vanadate-trapped. Cyclosporin A, which is considered a transport substrate but activates ATPase to a much lesser degree than verapamil, showed an intermediate average of FRET efficiencies centered on 0.5. When looking at the single-molecule FRET histograms for all four conditions, it is obvious that Pgp can adopt more than two major conformations (compared with the histograms of a three FRET-level system like F0F1-ATP synthase (53, 54)).

Detailed information about the number of distinguishable conformations is obtained from the two-dimensional FRET transition density plot (55). The FRET 1–2 transition plot for condition apo revealed only a few transitions, mostly in the 5.5–6.5-nm range. A different picture was obtained for verapamil transport, with two dominating transitions between 5.0 and 5.5 and 5.5 and 6.0 nm. A large number of forward and backward fluctuations with small distance changes in the range of 0.5 nm was observed. As the precision of FRET-based distance calculation is in a similar range given the number of detected photons per FRET level, we had to exclude possible fluorescence anisotropy artifacts. The single molecule anisotropy values measured for FRET donor and acceptor bound to Pgp were in the range of r = 0.1 (see supplemental Fig. S2). Therefore, an orientational fluorophore dipole moment artifact seems to be unlikely to cause the small FRET distance changes (42). The turnover number for ATP hydrolysis by Pgp under the conditions of the smFRET experiments is about one/s, which means that the average fluorescence burst (100–250 ms) will likely capture only substeps of one catalytic cycle. It is therefore possible that the two transitions centered on 5.2 and 5.8 nm represent distinct conformational changes and that, due to the slow turnover, only very few full transport cycles were observed.

Under conditions of vanadate trapping, the transition centered on 5.2 nm is most populated, again consistent with the ensemble experiments that showed the highest mean FRET efficiency for this condition. Considering that the nucleotide-binding site not occupied by ADP-Vi is still able to exchange nucleotide freely (51, 55), it is possible that the small transitions between 5 and 5.5 nm under this condition are due to motions in the helical subdomains of the NBDs (which contain the cysteines in mutant TS), motions that may be part of opening and closing of the unoccupied catalytic site.

The condition cyclosporin transport appears to shift the populations to several states, one with high FRET efficiency centered on 4.8 nm (that is present but barely populated under condition verapamil transport), one with intermediate efficiency (5.4 nm), and a low efficiency FRET state centered on 6 nm. As mentioned under “Results,” cyclosporin A is a relatively large transport substrate that activates ATP hydrolysis only a little above basal levels, and it is possible that conformations that are too short lived to be observed in significant numbers under condition verapamil transport are stabilized or prolonged with cyclosporin bound and could be identified as separate FRET levels.

The dwell time histograms in Fig. 9 show a long dwell time or average lifetime of each step to be 36 ms for the apo condition based on only a few detectable FRET level transitions. Verapamil transport has the shortest lifetime of all four conditions of 7.4 ms, consistent with rapid changes that would occur during ATP binding, hydrolysis, and drug translocation in a transport-stimulating condition. However, all FRET transitions were added into the dwell time histograms without sorting according to the respective FRET efficiencies. To correlate dwell times with sequential biochemical states of catalysis, future analysis will require longer time trajectories of the conformational changes as well as models to assign FRET levels to biochemical states, for example using Hidden Markov Models (35, 56). Two conditions known biochemically to slow down ATP hydrolysis compared with verapamil, vanadate-trapped and cyclosporin transport, have longer dwell times, meaning that the transitions between two different FRET efficiencies are slower under these conditions compared with verapamil transport. In an ATPase assay, vanadate binding reduces the activity to around ∼3% of drug stimulated activity. Although the dwell time for the vanadate-trapped enzyme is similar to the apo condition, more frequent FRET transitions occurred with vanadate, possibly due to rapid closing and opening of the unoccupied catalytic site (see above). Cyclosporin A exhibited a relatively short dwell time averaged over all FRET transitions, but these transitions were less frequent than for the verapamil transport condition.

Taken together, we have shown here that Pgp can sample a range of conformations that are populated differentially as a function of substrate conditions. Going from the apo conformation of Pgp as seen in the crystal structure to an outward-facing conformation as seen in ADP-bound Sav1866, for example, we were expecting at least one transition for mutant TS moving between 7 and 5 nm. However, the lack of such large conformational transitions (as evidenced by the absence of off-diagonal transitions in Fig. 8) lead us to believe that the catalytic cycle of Pgp instead proceeds via a series of relatively small steps. The small transitions we see support a model where the NBDs are never completely dissociated from one another during steady state catalysis (Fig. 10). However, the model presented in Fig. 10 is different from alternating site models proposed previously (16, 18, 57) in several aspects as follows.

FIGURE 10.

Working model of Pgp catalytic mechanism. The model is based on the alternating site mechanism (2, 16, 18, 57), and the data obtained are presented as FRET spectroscopy study. The cycle starts with addition of drug (verapamil) and MgATP to apo-Pgp (left) resulting in a transporter with two molecules of ATP sandwiched at the NBD-NBD interface (state A). If catalysis could not continue because of e.g. mutation in one or both catalytic sites, this state would represent the symmetric nucleotide sandwich seen in crystal structures. We speculate that binding of two MgATPs brings the two TMDs close together with a high affinity drug-binding site that may or may not be exposed to the cytoplasm or inner leaflet. A more closed TMD domain (compared with what is seen in the x-ray structure of apo-Pgp (11)) is still compatible with drug-stimulated ATP hydrolysis as shown in a recent cross-linking study (58). The presence of drug in the (possibly sequestered) TMD-binding site acts to stabilize the subsequent transition state in one catalytic site (here site 1) with tightly bound ATP in site 2. Collapse of the transition state in site 1 (leading to ADP-Pi in state B) converts the high affinity drug-binding site to low affinity by means of helix rotation in the TMDs (21), ultimately resulting in release of drug to the extracellular milieu. Helix rotation may be assisted by the free energy drop of Pi release leading to state C. ADP bound in site 1 is released (one of the rate-limiting steps) and replaced by ATP. Subsequent closing of site 1 allows the tightly bound ATP in site 2 to enter the transitions state to form state A′. Once state A′ is formed, the cycle repeats except that ATP hydrolysis now occurs in site 2. In presence of Vi, stage C or C′ will result in the vanadate-trapped state. For further details, see text.

Recent cross-linking studies from our laboratory and others (27, 58) showed that both the NBDs and the TMDs can be cross-linked without significant loss of drug-stimulated ATPase activity, suggesting that the wide separation of the NBDs and TMDs (at the cytoplasmic side) as seen in the crystal structure (11) is a conformation that may not be adopted during every cycle of steady state turnover. We therefore postulate that drug and nucleotide bindings result in a state with more closely associated TMDs and pseudo-symmetric ATP sandwich, in which one of the catalytic sites is poised for hydrolysis (state A in Fig. 10). This state is still inward-facing with a high affinity drug-binding site, but because the TMDs have a different conformation in this state compared with the apo-form, it may explain why photo-affinity labeling points to a reduced affinity for drugs under this condition (59). In the next step, hydrolysis of ATP in site 1 followed by collapse of the transition state (and Pi release) results in helix rotation in the TMDs (21), thus converting the high affinity drug-binding site to low affinity with subsequent dissociation of the drug (Fig. 10, state B). Although site 1 then opens just enough to allow release of ADP and binding of ATP, site 2 remains closed with occluded ATP (Fig. 10, state C). If vanadate is present, state C is converted to state D with ADP-Vi trapped in site 1. Note that as a result of vanadate trapping, the formerly occluded site 2 needs to convert back to a site that can exchange nucleotide freely (51, 55) with concomitant formation of the high affinity drug-binding site (60). During steady state turnover, ADP release and binding of ATP and drug converts state C to state A′, which is a mirror conformation of state A and another half-cycle starts leading back to state A.

The model presented here is supported by the FRET spectroscopy data in several ways. From the bulk measurements, the vanadate-trapped state displays the smallest D/A ratio, consistent with close association of the two NBDs. In the presence of an excess of MgATP, the nucleotide exchanging site 2 in state D is likely predominantly in a closed conformation with loosely bound ATP. Structurally, this state may resemble the symmetric nucleotide sandwich seen in crystal structures most closely. An intermediate D/A ratio was seen for all mutants under conditions of drug-stimulated ATP hydrolysis, consistent with the alternating opening and closing of catalytic sites. Note that mutant pairs TS and HD are located within the helical subdomain of the NBDs. The helical subdomain has been shown to undergo significant motions relative to the RecA-like domain in response to nucleotide binding in the maltose transporter from Escherichia coli (61). The ensemble FRET data also support the notion that drug binding alone does not result in a significant structural rearrangement that would affect the spatial arrangement of the two NBDs. The single-molecule FRET data support and extend the information gained from the ensemble measurements. For mutant TS, two major transitions are seen in distance 1–2 plots for condition verapamil transport, one between 5.5 and 6 nm and one between 5.5 and 5 nm, whereas upon vanadate trapping, the predominant transition is between 5 and 5.5 nm. We speculate the following: (i) the small transition in the presence of vanadate corresponds to small fluctuations of the helical domain of either NBD, similar to what has been observed in molecular dynamics simulations of AMPPNP-bound Sav1866 in which one nucleotide was removed from one catalytic site before performing the calculations (62); and (ii) the larger transitions under conditions of verapamil transport correspond to the collapse of the transition state in either NBD with concomitant opening of the catalytic site for nucleotide exchange.

However, it should be noted that the FRET data would also be consistent with a model in which hydrolysis of the first ATP results in drug transport, although the free energy gained from hydrolyzing the second ATP is utilized for an efficient resetting of the transporter to the ground state (2, 63–65). Such a model would still require cooperativity of the two NBDs (for which there is ample experimental evidence) but at the same time would allow complete dissociation of the NBDs between some or all catalytic cycles.

Here, we have shown that ensemble and single-molecule FRET spectroscopy can be applied to study the catalytic mechanism of mammalian P-glycoprotein. We showed that drug and nucleotide binding makes the NBDs come together, a state further promoted by trapping of ADP and vanadate in catalytic sites. With the vast substrate classes of Pgp, it would be of great interest to find a molecule that precludes the NBDs from close association, thereby inhibiting the transporter's interference with drug treatment. We have described a system that will allow future investigations of the dynamics of Pgp during its transport cycle. Further studies, especially in real time, are needed to visualize all the conformations that Pgp is undergoing during drug-stimulated ATP hydrolysis (66). Such studies will require D/A pairs not only located within the NBDs but also in the TMDs and intracellular loops or “coupling helices” to further the understanding of the communication between the TMDs, NBDs, ATP hydrolysis, and drug extrusion. Ultimately, these studies will require trapping Pgp in the laser focus for prolonged observations. Such longer observation times have recently been achieved with the “Anti-Brownian Electrokinetic” (ABEL) trap method (67, 68), which is in developmental stages (69) in our laboratories for future Pgp dynamics analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The cysteine-less mouse Mdr3 construct was kindly provided by Drs. Gregory Tombline and Alan Senior, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY. We thank Drs. Tom Duncan and Stewart Loh for the use of the fluorimeter and for many helpful discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants CA100246 and GM058600 (to S. W.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

We used Sav1866 (Protein Data Bank code 2hyd (36)) as a template because a crystal structure of Pgp was not available at the time.

- ABC

- ATP-binding cassette

- cps

- counts/s

- Pgp

- P-glycoprotein

- NBD

- nucleotide binding domain

- TMD

- transmembrane domain

- D/A

- donor to acceptor

- ATPγS

- adenosine 5′-O-(3-thio)triphosphate

- DDM

- n-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside

- TCEP

- tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- CHAPS

- 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propane sulfonate/N,N-dimethyl-3-sulfo-N-[3-[[3α,5β,7α,12α)-3,7,12-trihydroxy-24-oxocholan-24-yl]amino]propyl]-1-propanaminium hydroxide

- PC

- phosphatidylcholine

- PA

- phosphatidic acid

- cpms

- counts/ms

- smFRET

- single-molecule FRET

- AMPPNP

- adenosine 5′-(β,γ-imino)triphosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rees D. C., Johnson E., Lewinson O. (2009) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 218–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jones P. M., O'Mara M. L., George A. M. (2009) Trends Biochem. Sci. 34, 520–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kos V., Ford R. C. (2009) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 3111–3126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holland I. B., Blight M. A. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 293, 381–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dean M., Hamon Y., Chimini G. (2001) J. Lipid Res. 42, 1007–1017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Juliano R. L., Ling V. (1976) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 455, 152–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gottesman M. M., Ling V. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 998–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sharom F. J. (2008) Pharmacogenomics 9, 105–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gottesman M. M., Fojo T., Bates S. E. (2002) Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 48–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Higgins C. F. (2007) Nature 446, 749–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aller S. G., Yu J., Ward A., Weng Y., Chittaboina S., Zhuo R., Harrell P. M., Trinh Y. T., Zhang Q., Urbatsch I. L., Chang G. (2009) Science 323, 1718–1722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dey S., Ramachandra M., Pastan I., Gottesman M. M., Ambudkar S. V. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 10594–10599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Loo T. W., Bartlett M. C., Clarke D. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 39706–39710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lugo M. R., Sharom F. J. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 643–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Urbatsch I. L., Tyndall G. A., Tombline G., Senior A. E. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 23171–23179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sauna Z. E., Kim I. W., Nandigama K., Kopp S., Chiba P., Ambudkar S. V. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 13787–13799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Al-Shawi M. K., Omote H. (2005) J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 37, 489–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Siarheyeva A., Liu R., Sharom F. J. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 7575–7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Delannoy S., Urbatsch I. L., Tombline G., Senior A. E., Vogel P. D. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 14010–14019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Urbatsch I. L., Sankaran B., Weber J., Senior A. E. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 19383–19390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gutmann D. A., Ward A., Urbatsch I. L., Chang G., van Veen H. W. (2010) Trends Biochem. Sci. 35, 36–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]