Abstract

Background. The decline in influenza vaccine efficacy in older adults is associated with a limited ability of current split-virus vaccines (SVVs) to stimulate cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses required for clinical protection against influenza.

Methods. The Toll-like receptor 4 agonist glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant–stable emulsion (GLA-SE) was combined with SVV to stimulate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in vitro to determine the cytokine response in dendritic cell subsets. Stimulated PBMCs were then challenged with live influenza virus to mimic the response to natural infection following vaccination, using previously identified T-cell correlates of protection.

Results. GLA-SE significantly increased the proportion of myeloid dendritic cells that produced tumor necrosis factor α, interleukin 6, and interleukin 12. When combined with SVV to stimulate PBMCs in vitro, this effect of GLA-SE was shown to regulate a T-helper 1 cell response upon challenge with live influenza virus; interleukin 10 production was suppressed, thus significantly increasing the interferon γ to interleukin 10 ratio and the cytolytic (granzyme B) response to influenza virus challenge, both of which have been shown to correlate with protection against influenza in older adults.

Conclusions. Our findings suggest that a novel adjuvant, GLA-SE, combined with standard SVV has the potential to significantly improve vaccine-mediated protection against influenza in older adults.

Influenza virus infection can cause life-threatening complications in older adults. Annual vaccination is considered the best strategy to contain the virus and prevent its associated morbidity and mortality in this vulnerable population. However, the current seasonal split-virus influenza vaccines (SVVs) have limited effectiveness among people aged >65 years [1].

The activation of innate immune mechanisms is critical to stimulating adaptive immune responses against intracellular pathogens such as influenza virus. The well-known defects in innate and adaptive immune responses in older adults are major contributors to the poor vaccine efficacy in this population [2]. The age-related decline in innate immune function reduces antigen presentation by dendritic cells [3] and can substantially alter the activation of an already compromised adaptive immune response; defects in both memory and effector T-cell function further contribute to diminished T-cell responses to vaccination in older adults [4, 5].

A practical approach to designing new vaccines is to add adjuvants to the existing SVVs to overcome the defects in the aged immune system. Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists are currently being explored as vaccine adjuvants to enhance immunogenicity [6]. TLRs expressed on innate immune cells, including dendritic cells, recognize and bind to the conserved molecular patterns of viruses, bacteria, and fungi, a process that initiates the innate immune response. This response can be triggered by TLR agonists, which mimic these pathogens and stimulate dendritic cells to produce T-helper 1 (Th1) cell–promoting cytokines, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and interleukin 12 (IL-12) [7].

TLR agonists have been shown to activate dendritic cells from aged mice and to enhance their ability to stimulate priming of aged naive CD4+ T cells and their subsequent proliferation and differentiation to effector T cells [8]. Polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly I:C), a TLR3 agonist, has been shown to enhance the maturation of dendritic cells, which promote Th1-cell responses and antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activation [9, 10]. The TLR4 agonist monophosphoryl lipid A has also been shown to promote a Th1-cell response in mice [11, 12]. Because there is a shift from Th1 to Th2 cytokine responses with aging, TLR adjuvants offer the possibility of reversing this defect when added to influenza vaccine. A Th1 cell–mediated increase in the CTL response to vaccination could contribute to improved clinical protection against severe disease when antibodies fail to provide sterilizing immunity and prevent infection in older adults [13]. We have shown in this population that higher ratios of Th1:Th2 cytokines (interferon γ [IFN-γ]:IL-10) and higher levels of CTL (granzyme B [GrzB]) activity in influenza A/H3N2–stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) provide more-sensitive correlates of protection against influenza, compared with serologic responses to vaccination [14, 15].

To facilitate the translation of preclinical studies in animal models to phase I vaccine trials in older adults, we have developed a novel model for preclinical testing of adjuvants combined with SVV to determine their effect on T-cell responses to influenza virus challenge. In this study, we evaluated a novel TLR4 agonist, glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant–stable emulsion (GLA-SE), for its potential to enhance the Th1 cell–mediated CTL response to influenza virus in older adults. We found that GLA-SE can activate myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) to produce high levels of Th1 cell–promoting cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12. We further show that stimulation of PBMCs with the GLA-SE–adjuvanted SVV enhances the Th1-cell response to live influenza virus challenge by suppressing IL-10 production, thereby increasing the ratio of IFN-γ:IL-10 and GrzB activity produced in response to influenza virus challenge in young and older adults.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study Design and Participants

Healthy adult volunteers, of whom 12 were young (aged 20–30 years) and 15 were older (aged >65 years), were recruited by written informed consent from the community of Greater Vancouver, Canada. Subjects were studied before and after influenza vaccination to evaluate the in vitro effects of different adjuvants on cytokine production by dendritic cells and their combined effect with SVV on the response to influenza virus challenge. Blood samples obtained from study participants were de-identified at the time of collection. The study protocol and informed consent form were approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board, University of British Columbia.

Procedures

The study participants were recruited to the center in the fall of 2009. Blood samples (35 cm3 heparinized whole blood) were drawn for isolation and in vitro stimulation of PBMCs with different TLR agonists and SVV, followed by a live influenza virus challenge with influenza A/Victoria/3/75 (A/H3N2). Our previous studies have demonstrated no difference in the T-cell response to older (A/Victoria/3/75) compared with more recently circulating A/H3N2 strains [13], probably because of the conserved T-cell epitopes within the subtypes of influenza virus.

Materials

GLA is a synthetic lipid A derivative and a TLR4 agonist [16]. The GLA-SE is an oil-in-water emulsion formulation prepared by mixing aqueous GLA with squalene oil as previously described [17]. GLA-SE was a gift from Steve Reed (Immune Design). Poly I:C was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals.

SVV containing A/Solomon Islands/3/2006 (HIN1), A/Wisconsin/67/2005 (H3N2), and B/Malaysia/2506/2004 (2008–2009 preservative-free formulation) was purchased from Sanofi Pasteur. Live-virus preparations of A/Victoria/3/75 (sucrose-gradient purified) were purchased from Charles River.

Preparation and Stimulation of PBMC Cultures

PBMCs were prepared from heparinized whole blood (35 cm3) by Ficoll-Paque Plus (Amersham) gradient purification, treated with RBC lysis solution (Bio-Rad) to remove red blood cells, washed, and resuspended in AIM-V media (Gibco Laboratories). A total of 1 mL of suspended cells (2 × 106 cells/mL) was added to 24-well multiplates (Nalge Nunc) and cultured with different doses of adjuvant (poly I:C: 20 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, or 100 μg/mL; or GLA-SE: 5 μg/mL or 10 μg/mL) and SVV (0.1 μg/mL or 0.4 μg/mL) under standard conditions for 5 days, after which supernatants were removed. PBMCs were washed and then stimulated with A/Victoria/3/75 (multiplicity of infection, 2), in 0.6 mL of AimV media for 20 hours. Cell culture supernatants were removed for IFN-γ and IL-10 assays, and PBMC lysates were prepared for GrzB assays.

Multiplex Assays

Bio-Plex multiplex cytokine assays measuring IFN-γ and IL-10 (Bio-Rad Laboratories) were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, 50 μL of cell culture supernatant was incubated with antibody-coupled beads. Complexes were washed, incubated with biotinylated detection antibody, and, finally, incubated with streptavidin-phycoerythrin. Cytokine concentration was measured against human recombinant cytokine standards by multiplex array reader and software (Luminex Instrumentation System and Bio-Plex Workstation [Bio-Rad Laboratories]).

GrzB Assay

GrzB activity in PBMC lysates was measured as previously validated [18]. In brief, the influenza virus–stimulated PBMCs were lysed in 200 μL of lysis buffer, nuclear debris was pelleted after 3 freeze-thaw cycles, and the lysate was removed and frozen at −80ºC. GrzB activity in the lysate (20 μL) was measured by cleavage of the substrate IEPDpna (BACHEM). GrzB activity was measured against a commercially available GrzB standard (Biomol), adjusted for protein concentration in the lysate (BCA [Pierce]), and calculated as units per milligram of protein.

Flow Cytometry and Antibodies

Two million PBMCs were added to each well of 48-well multiplates (Nalge Nunc) and cultured in 1 mL of AIM V media containing GLA (10 μg/mL [Immune Design]), poly I:C (50 μg/mL [Alexis Biochemicals]), and/or SVV (0.1 μg/mL) for 6 hours. Brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) was added for 3 hours, and then the cells were harvested, fixed in BD FACS lysing solution, and stored at −80 C. Cells were prepared for flow cytometric analysis by resuspension in BD FACS permeabilization solution and staining as described previously [19]. Antibodies included anti–CD123-AmCyan, anti–CD11c-APC, anti–MHCII-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti–CD14-PE-Cy7, anti–IL6-APC-Cy7, and anti–TNF-α-Alexa700, from BD Pharmingen; and anti–IL12p40/70-Pacific Blue, from eBioscience. Data were acquired on a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Statistical Analysis

As the data were not normally distributed for all comparisons, nonparametric tests (ie, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired data) were used to detect differences in the response to different SVV/adjuvant combinations versus control PBMC cultures in young and older adults; differences in the response between the 2 age groups were evaluated using the Mann–Whitney U test (for unpaired data). Statistical significance was established at P < .05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 16.0 (IBM SPSS).

RESULTS

GLA-SE Stimulates Th1 Cell–Promoting Cytokines by mDCs

PBMCs were stimulated with poly I:C (TLR3 agonist; positive control) or the oil-in-water emulsion GLA-SE (TLR4 agonist), alone or in combination with SVV, and compared with an unstimulated control. Poly I:C was selected as it had been previously shown to induce Th1 cell–promoting cytokine production through TLR3 ligation [20] and to effectively stimulate mDCs from aged mice [21]. GLA-SE has been shown to stimulate a Th1-cell response through TLR4 ligation in mouse and nonhuman primate models [22]. We had previously shown a dose-response increase in TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 levels in supernatants of PBMCs stimulated with poly I:C/SVV; the levels of these cytokines were similar in young and older adults (unpublished data). Thus, we were interested in determining the source of these Th1 cell–promoting cytokines.

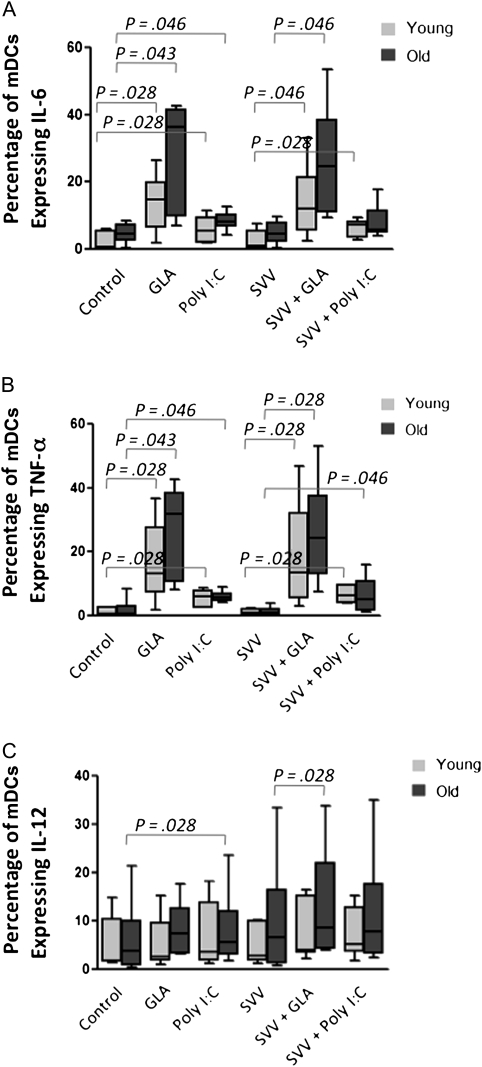

Our preliminary studies showed that only mDCs were activated by poly I:C and GLA-SE, consistent with the fact that plasmacytoid dendritic cells do not express either TLR3 or TLR4 [7]. As a result, we focused on cytokine production by mDCs in all subsequent studies. As shown in Figure 1, GLA-SE significantly enhanced the percentage of mDCs expressing IL-6 and TNF-α in young (Figure 1A; P = .028) and older (Figure 1B; P = .043) subjects. Poly I:C also increased the percentage of mDCs expressing IL-6 and TNF-α in samples from young (P = .028) and older (P = .046) subjects, respectively. The proportion of mDCs expressing IL-1 was below the limits of detection under these conditions. Stimulation with SVV alone did not have any effect on TNF-α or IL-6 production by mDCs, thus demonstrating that SVV does not contribute to the stimulation of mDCs. Furthermore, the addition of adjuvants plus SVV did not provide a further increase in the levels of these cytokines, compared with the adjuvants alone (Figure 1A and 1B). Poly I:C significantly increased the percentage of mDCs expressing IL-12 in older subjects, as did the addition of GLA-SE to SVV (Figure 1C; P = .028).

Figure 1.

Glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant–stable emulsion (GLA-SE) increased the percentage of myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) expressing interleukin 6 (IL-6; A), tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα; B), or interleukin 12 (IL-12; C). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were treated for 6 hours with GLA-SE or polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly I:C), with or without split-virus vaccine (SVV), and intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) was used to determine the proportion of mDCs expressing these cytokines. Mean proportions of ICS-positive mDCs are shown for each of the conditions (samples are from 6 young subjects and 6 older subjects). Box plots show median values and interquartile ranges, and error bars represent the range of values. P values indicate the levels of significance in nonparametric comparisons.

GLA-SE Added to SVV Enhances the GrzB Response to Influenza Virus Challenge

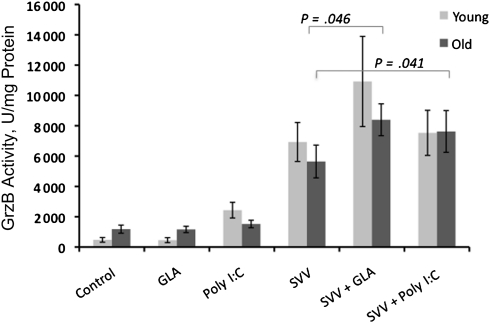

GrzB activity as a measure of CTL activity in PBMCs challenged ex vivo (for 20 hours) with live influenza virus has been shown to correlate with protection against influenza in vaccinated older adults [14, 15]. We used this 20-hour live-virus challenge following in vitro exposure to different adjuvant/SVV combinations, to determine whether the Th-cell (IFN-γ:IL-10 ratio) and CTL (GrzB) responses to influenza virus were altered by the adjuvant/SVV. Consistent with our preliminary studies, treatment with SVV enhanced GrzB activity in response to virus challenge in PBMCs from young and older subjects. The adjuvant/SVV effect on IFN-γ:IL-10 and GrzB responses was demonstrated both before and after vaccination but were not as robust before vaccination. Prevaccination data are presented to demonstrate that the enhanced response could be stimulated in the absence of recent vaccination and that it was less likely to have been confounded by subject exposure to pandemic H1N1 during the 2009–2010 influenza season.

Treatment with SVV plus GLA-SE and with SVV plus poly I:C significantly enhanced this increase in GrzB activity in samples from older subjects (Figure 2; P = .046 and .041, respectively). Treatment with GLA-SE or poly I:C in the absence of SVV showed minimal background levels of GrzB activity, similar to untreated controls. We additionally tested 2 other adjuvants, an aqueous GLA formulation (GLA-AF) and a TLR 7/8 adjuvant (R848) and showed that, under similar experimental conditions, neither of these adjuvants enhanced SVV-mediated GrzB activity (data not shown). Interestingly, a cocktail of TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 added to the PBMC cultures at similar concentrations to those induced by the adjuvants completely suppressed the GrzB response to SVV (unpublished data). These results contrast with those in aged mice, in which this cocktail reversed the age-related decline in CD4+ cognate T-cell function [23]. This result suggests that the requirements for restimulating influenza virus–specific T-cell memory in older people may be different from those needed to stimulate a naive T-cell response in aged mice.

Figure 2.

Glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant–stable emulsion (GLA-SE) enhanced the split-virus vaccine (SVV)–mediated increase in granzyme B (GrzB) activity in response to live influenza virus challenge. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were cultured with GLA-SE or polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly I:C), with or without SVV, for 5 days, followed by challenge with live influenza virus for 20 hours. Mean levels of GrzB activity measured in PBMC lysates are shown (young subjects, n = 11; old subjects, n = 14). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. P values indicate the levels of significance in nonparametric comparisons.

Enhancement of CTL Activity by GLA-SE Is Associated With Suppression of IL-10

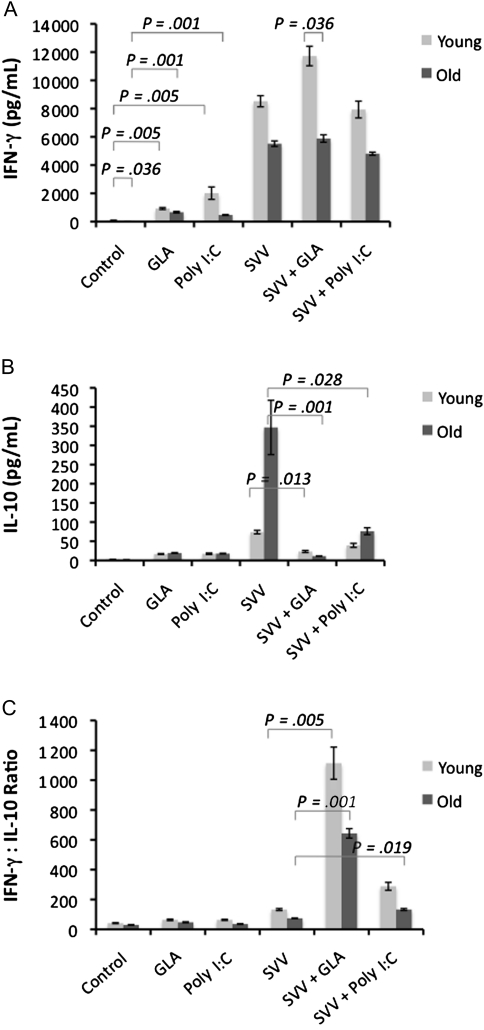

As with GrzB, the IFN-γ:IL-10 ratio in influenza virus–stimulated PBMCs has been shown to correlate with protection in older adults [14]. To investigate the adjuvant effect of GLA-SE or poly I:C on the T-cell response to SVV, we examined how the levels of IFN-γ relative to IL-10 were altered in the response to influenza virus. Following stimulation with different SVV/adjuvant combinations for 5 days, cytokines were measured in PBMC supernatants following a 20-hour live-virus challenge. SVV significantly increased the levels of IFN-γ in response to influenza virus challenge, compared with unstimulated controls (Figure 3A); the addition of adjuvants to SVV did not alter this response. There was a small but significant increase in IFN-γ levels in PBMCs treated with adjuvant alone in young (P = .005) and older (P = .001) subjects; this result could be attributed to direct stimulation of natural killer cells by adjuvants. In general, IFN-γ levels were low in older compared with younger subjects; the difference was statistically significant in untreated control PBMCs and GLA-SE/SVV–treated samples (Figure 3A; P = .036).

Figure 3.

Glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant–stable emulsion (GLA-SE) significantly reduced the split-virus vaccine (SVV)–mediated increase in the interleukin 10 (IL-10) response to influenza virus challenge, increasing the ratio of interferon γ (IFN-γ) to IL-10. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were cultured with GLA-SE or poly I:C, with or without SVV, for 5 days, followed by challenge with live influenza virus for 20 hours. Mean IFN-γ (A) and IL-10 (B) levels and the IFN-γ:IL-10 ratio (C) in PBMC culture supernatants (young subjects, n = 11; old subjects, n = 14) are shown. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. P values indicate the levels of significance in nonparametric comparisons.

The most dramatic effect of the adjuvants was the reduction in the IL-10 response to live-virus challenge in older adults (Figure 3B). IL-10 levels were 5-fold higher in older compared with young adults in PBMCs that had been stimulated with SVV alone prior to influenza virus challenge the addition of GLA-SE to SVV resulted in a >10-fold reduction in IL-10 levels relative to SVV alone in older adults (P = .001) and a 4-fold reduction in younger subjects (P = .013) in response to influenza virus challenge. Poly I:C also suppressed SVV-mediated IL-10 production but was significant only in older subjects (P = .028). As shown in Figure 3C, the reduction in IL-10 resulted in significantly higher ratios of IFN-γ:IL-10 in GLA-SE/SVV–treated PBMCs, compared with SVV alone, in young (P = .005) and older (P = .001) subjects. Similarly, the IFN-γ:IL10 ratio was increased by poly I:C/SVV in PBMCs from older subjects (P = .019).

Thus, the net adjuvant effect is the increase in TLR-mediated production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12, which results in suppression of IL-10 in response to influenza virus challenge and the associated increase in the IFN-γ:IL-10 ratio and GrzB activity.

DISCUSSION

Innate and adaptive cell-mediated immune responses are essential players in the elimination of viral pathogens. Successful vaccine formulations should activate these responses to optimize protection against influenza. SVVs provide a weak stimulus, particularly to innate immune mechanisms that could restimulate CTL memory, thus contributing to the limited efficacy of these vaccines in older people. In this study, we show that these shortcomings of SVV can be overcome by adding TLR agonists to SVV. Our results suggest that GLA-SE and poly I:C activate mDCs to produce Th1 cell–promoting cytokines and, when combined with SVV, suppress IL-10 production with an associated increase in the IFN-γ:IL-10 ratio (Th1/Th2) and GrzB activity. The increase in IL-10 production in older relative to young adults is age-related and not due to differences in prior influenza exposure [24]. These results complement findings in animal models and suggest that GLA-SE could be added to SVV to improve influenza vaccine efficacy in older adults.

The oil-in-water emulsion GLA-SE adjuvant is a novel TLR4 agonist previously shown to be safe and well tolerated in human subjects in a phase I clinical trial [6]. GLA combined with Fluzone (SVV) was also shown (in hemagglutination-inhibition assays) to effectively enhance the antibody response and to shift the immune response toward a Th1-cytokine response in a mouse model [6]. Recently, Coler et al [25] have shown in vitro that GLA can induce the maturation of murine and human dendritic cells with a concomitant release of Th1 cell–promoting cytokines and chemokines by these cells. In vivo, GLA produced a shift toward a Th1 cell–mediated response to the coadministered vaccine antigen with a reduction in the IL-10 response to live-virus challenge. Our in vitro experiments in human PBMC reproduced this effect of GLA-SE resulting in a substantial shift toward a Th1 cytokine response and increased GrzB activity. These results suggest that substantial benefit could be gained from adding GLA-SE to seasonal SVV.

A cocktail of TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 was shown to overcome age-related defects in the cognate function of naive CD4+ T cells in mouse models [23]. However, we demonstrated in PBMCs from older adults that this cocktail, when added to SVV, suppressed the IFN-γ:IL-10 ratio and GrzB response to influenza virus challenge relative to SVV alone, consistent with the well-described association between increased levels of inflammatory cytokines and immune suppression in older people [26]. Similar to our results, TLR agonists coadministered with antigen increased dendritic cell production of these cytokines and improved cognate function in naive CD4+ T cells in young and aged mice [8]. The improvement in aged CD4+ T-cell response was further shown in vitro to be dependent on IL-6 production by antigen-presenting cells, because addition of anti–IL-6 blocking antibody abolished the boost in the aged CD4+ T-cell response [8]. This result suggests that IL-6 is key to boosting T-cell stimulation with SVV. Auray et al [27] showed that the expression of IL-6 and TNF-α was significantly increased on stimulation of porcine monocyte–derived dendritic cells with lipopolysaccharide (TLR4) or poly I:C (TLR3). Further, Makela et al [28] showed that TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12 were synergistically induced upon stimulation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells with lipopolysaccharide and poly I:C. By use of TNF knockout mice, Trevejo et al [29] showed that maturation of dendritic cells by TNF-α was required for activation of both Th cells and CTLs. IL-12 augments the Th1-cell response by increasing IFN-γ production, which is key for clearance of intracellular pathogens [30]. Thus, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12 appear to be important in driving the Th1 cell–mediated responses observed in our study.

CTLs eliminate virus-infected cells through a mechanism that involves GrzB-mediated apoptosis of infected cells. In this study, GrzB activity was used as a measure of CTL activation. Of the 4 TLR agonists, only GLA-SE and, to a lesser degree, poly I:C were able to enhance the SVV-mediated increase in GrzB activity, while the other 2 adjuvants, the aqueous GLA formulation (GLA-AF) and the TLR 7/8 agonist R848, had no effect. Our finding that SVV adjuvanted with GLA-SE significantly enhanced GrzB activity in PBMC samples from older subjects may be highly relevant to enhancing the effect of current SVV in the older population because low GrzB activity in influenza virus–stimulated PBMCs directly correlates with development of influenza in vaccinated older adults [14]. The possibility of direct stimulation by GLA-SE on T cells expressing TLR4 is being explored in our ongoing experiments.

It is important to note that SVV rather than subunit influenza vaccine (SuV) was used in our study. A major difference between SVV and SuV is the protein composition: SVV contains all the virus proteins, whereas SuV contains only hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. The number of CTL epitopes on the various influenza A virus proteins has been predicted to be 167, using sequence comparison to identify conserved regions on influenza virus proteins [31, 32]. Of these epitopes only 1 is on hemagglutinin and 7 are on neuraminidase. Nucleoprotein contains 17 putative epitopes, and an additional 142 epitopes were on the polymerase or matrix proteins, which are not present in SuV. When stimulating PBMCs with SVV, all influenza virus proteins are present and could theoretically restimulate a large number of CTL clones induced by earlier infections and specific for any of the influenza virus proteins. Accordingly, the number of CTL clones, which potentially could be activated and produce GrzB, is much lower for SuV than for SVV.

TLR agonists operate through the innate immune system. In contrast to the well-established decline in T-cell–mediated immunity, innate immune function with respect to the expression of TLR on mDCs appears to be preserved with aging [21], but TLR function may need to be restimulated by TLR ligands before it can be fully functional [33]. We have shown that the preserved function of mDCs in older adults can be exploited using TLR agonists to stimulate mDCs to produce higher levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12. Our findings agree with those of Agrawal et al [34, 35], who showed that TLR agonists stimulated higher levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IFN-α in monocyte-derived dendritic cells from older compared with young adults. Similarly, other studies showed no significant differences in the number, phenotypic markers, and activation in response to TLR agonists between dendritic cells from older versus young subjects [21, 34, 36, 37]. Panda et al [21] have recently shown that an age-associated defect in transcription and posttranslational mechanisms in TLR gene expression contributes to decreased activation of both mDCs and plasmacytoid dendritic cells in response to different TLR agonists. However, TLR4-mediated activation was not investigated in their study. Thus, the reversibility of age-related changes in mDCs may be limited to particular TLRs.

In summary, GLA-SE is a stable oil-in-water emulsion adjuvant that has been shown to be safe and well tolerated in humans. Our study shows that GLA-SE effectively stimulates mDCs to promote a Th1-cell response to SVV by suppressing IL-10 production and enhancing the CTL (GrzB) response to influenza virus challenge. The next step is to determine whether these results translate to ex vivo T-cell responses to influenza virus challenge in clinical trials of SVV/GLA-SE, to demonstrate its potential for enhanced protection against influenza in older people.

Notes

Acknowledgments.

We thank Gale Tedder for her outstanding commitment to study recruitment and coordination; David Chai and Dominica Kwok for their excellent technical assistance; and Alison Kleppinger from the Center on Aging, University of Connecticut Health Center (Farmington), for performing the statistical analysis.

Financial support.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (U01 AI074449). The Network of Centres of Excellence in Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics in Canada supported the development of the GrzB assay, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research supported the validation of the GrzB activity and cytokine assays, according to International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines. The study was conducted through the VITALiTY Research Unit, Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute (Vancouver, BC, Canada).

Potential conflicts of interest.

J. E. M. has participated on advisory boards for GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur, Novartis, and Med-Immune and on data-monitoring boards for Sanofi Pasteur; has received research grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and GlaxoSmithKline; has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and Sanofi Pasteur; and has received honoraria and travel and accommodation reimbursements for presentations sponsored by Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and Sanofi Pasteur, as well as travel and accommodation reimbursements for participation on a publication steering committee for GlaxoSmithKline. S. G. R. is founder and director of Immune Design. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Monto AS, Ansaldi F, Aspinall R, et al. Influenza control in the 21st century: Optimizing protection of older adults. Vaccine. 2009;27:5043–53. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sambhara S, McElhaney JE. Immunosenescence and influenza vaccine efficacy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;333:413–29. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-92165-3_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grewe M. Chronological ageing and photoageing of dendritic cells. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:608–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haynes L. The effect of aging on cognate function and development of immune memory. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:476–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou X, McElhaney JE. Age-related changes in memory and effector T cells responding to influenza A/H3N2 and pandemic A/H1N1 strains in humans. Vaccine. 2011;29:2169–77. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coler RN, Baldwin SL, Shaverdian N, et al. A synthetic adjuvant to enhance and expand immune responses to influenza vaccines. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schreibelt G, Tel J, Sliepen KH, et al. Toll-like receptor expression and function in human dendritic cell subsets: implications for dendritic cell-based anti-cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59:1573–82. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0833-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones SC, Brahmakshatriya V, Huston G, Dibble J, Swain SL. TLR-activated dendritic cells enhance the response of aged naive CD4 T cells via an IL-6-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2010;185:6783–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams M, Navabi H, Jasani B, et al. Dendritic cell (DC) based therapy for cervical cancer: use of DC pulsed with tumour lysate and matured with a novel synthetic clinically non-toxic double stranded RNA analogue poly [I]:poly [C(12)U] (Ampligen R) Vaccine. 2003;21:787–90. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00599-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navabi H, Jasani B, Reece A, et al. A clinical grade poly I:C-analogue (Ampligen) promotes optimal DC maturation and Th1-type T cell responses of healthy donors and cancer patients in vitro. Vaccine. 2009;27:107–15. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore A, McCarthy L, Mills KH. The adjuvant combination monophosphoryl lipid A and QS21 switches T cell responses induced with a soluble recombinant HIV protein from Th2 to Th1. Vaccine. 1999;17:2517–27. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldridge JR, McGowan P, Evans JT, et al. Taking a Toll on human disease: Toll-like receptor 4 agonists as vaccine adjuvants and monotherapeutic agents. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:1129–38. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.7.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shahid Z, Kleppinger A, Gentleman B, Falsey AR, McElhaney JE. Clinical and immunologic predictors of influenza illness among vaccinated older adults. Vaccine. 2010;28:6145–51. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McElhaney JE, Xie D, Hager WD, et al. T cell responses are better correlates of vaccine protection in the elderly. J Immunol. 2006;176:6333–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McElhaney JE, Ewen C, Zhou X, et al. Granzyme B: correlates with protection and enhanced CTL response to influenza vaccination in older adults. Vaccine. 2009;27:2418–25. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coler RN, Bertholet S, Shaverdian N, et al. A synthetic adjuvant to enhance and expand immune responses to influenza vaccine. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox CB, Anderson RC, Dutill TS, Goto Y, Reed SG, Vedvick TS. Monitoring the effects of component structure and source on formulation stability and adjuvant activity of oil-in-water emulsions. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2008;65:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gijzen K, Liu WM, Visontai I, et al. Standardization and validation of assays determining cellular immune responses against influenza. Vaccine. 2010;28:3416–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kollmann TR, Crabtree J, Rein-Weston A, et al. Neonatal innate TLR-mediated responses are distinct from those of adults. J Immunol. 2009;183:7150–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang CC, Duffy KE, San Mateo LR, Amegadzie BY, Sarisky RT, Mbow ML. A pathway analysis of poly(I:C)-induced global gene expression change in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Physiol Genomics. 2006;26:125–33. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00002.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tesar BM, Walker WE, Unternaehrer J, et al. Murine [corrected] myeloid dendritic cell-dependent toll-like receptor immunity is preserved with aging. Aging Cell. 2006;5:473–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coler RN, Bertholet S, Moutaftsi M, et al. Development and characterization of synthetic glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant system as a vaccine adjuvant. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haynes L, Eaton SM, Burns EM, Rincon M, Swain SL. Inflammatory cytokines overcome age-related defects in CD4 T cell responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2004;172:5194–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skowronski DM, Hottes TS, McElhaney JE, et al. Immuno-epidemiologic correlates of pandemic H1N1 surveillance observations: higher antibody and lower cell-mediated immune responses with advanced age. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:158–67. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coler RN, Bertholet S, Moutaftsi M, et al. Development and characterization of synthetic glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant system as a vaccine adjuvant. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, et al. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Auray G, Facci MR, van Kessel J, Buchanan R, Babiuk LA, Gerdts V. Differential activation and maturation of two porcine DC populations following TLR ligand stimulation. Mol Immunol. 2010;47:2103–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makela SM, Strengell M, Pietila TE, Osterlund P, Julkunen I. Multiple signaling pathways contribute to synergistic TLR ligand-dependent cytokine gene expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages and dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:664–72. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0808503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trevejo JM, Marino MW, Philpott N, et al. TNF-alpha-dependent maturation of local dendritic cells is critical for activating the adaptive immune response to virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12162–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211423598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a cytokine produced by antigen-presenting cells with immunoregulatory functions in the generation of T-helper cells type 1 and cytotoxic lymphocytes. Blood. 1994;84:4008–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jameson J, Cruz J, Terajima M, Ennis FA. Human CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocyte memory to influenza A viruses of swine and avian species. J Immunol. 1999;162:7578–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang M, Lamberth K, Harndahl M, et al. CTL epitopes for influenza A including the H5N1 bird flu; genome-, pathogen-, and HLA-wide screening. Vaccine. 2007;25:2823–31. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agius E, Lacy KE, Vukmanovic-Stejic M, et al. Decreased TNF-alpha synthesis by macrophages restricts cutaneous immunosurveillance by memory CD4+ T cells during aging. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1929–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agrawal A, Agrawal S, Cao JN, Su H, Osann K, Gupta S. Altered innate immune functioning of dendritic cells in elderly humans: a role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase-signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2007;178:6912–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agrawal A, Tay J, Ton S, Agrawal S, Gupta S. Increased reactivity of dendritic cells from aged subjects to self-antigen, the human DNA. J Immunol. 2009;182:1138–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steger MM, Maczek C, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Morphologically and functionally intact dendritic cells can be derived from the peripheral blood of aged individuals. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:544–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-790.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lung TL, Saurwein-Teissl M, Parson W, Schonitzer D, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Unimpaired dendritic cells can be derived from monocytes in old age and can mobilize residual function in senescent T cells. Vaccine. 2000;18:1606–12. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00494-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]