Abstract

The ovarian peptide hormone, relaxin, circulates during pregnancy, contributing to profound maternal vasodilation through endothelial and nitric oxide (NO)–dependent mechanisms. Circulating numbers of bone marrow–derived endothelial cells (BMDECs), which facilitate angiogenesis and contribute to repair of vascular endothelium, increase during pregnancy. Thus, we hypothesized that relaxin enhances BMDEC NO production, circulating numbers, and function. Recombinant human relaxin-2 (rhRLX) stimulated PI3K/Akt B-dependent NO production in human BMDECs within minutes, and activated BMDEC migration that was inhibited by L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester. In BMDECs isolated from relaxin/insulin-like family peptide receptor 2 gene (Rxfp2) knockout and wild-type mice, but not Rxfp1 knockout mice, rhRLX rapidly increased NO production. Similarly, rhRLX increased circulating BMDEC number in Rxfp2 knockout and wild-type mice, but not Rxfp1 knockout mice as assessed by colony formation and flow cytometry. Taken together, these results indicate that relaxin effects BMDEC function through the RXFP1 receptor. Finally, both vascularization and incorporation of GFP-labeled BMDECs were stimulated in rhRLX-impregnated Matrigel pellets implanted in mice. To conclude, relaxin is a novel regulator of BMDECs number and function, which has implications for angiogenesis and vascular remodeling in pregnancy, as well as therapeutic potential in vascular disease.

Introduction

Dramatic changes in systemic and renal hemodynamics occur during pregnancy. There is a marked decrease in systemic vascular resistance and reciprocal increases in cardiac output and global arterial compliance, accompanied by a modest decline in mean arterial pressure. The renal circulation participates in this maternal vasodilatory response; consequently, renal plasma flow and glomerular filtration rate rise by 80% and 50%, respectively. Although understanding of the mechanisms underlying these maternal adaptations to pregnancy is incomplete, there is increasing evidence that the ovarian peptide hormone relaxin plays a key role.1 Originally isolated from the ovary by Hisaw,2 relaxin was named for its ability to relax the pubis symphysis in some species. In nonhuman primates, it was subsequently shown by the same investigators to cause morphologic changes in endothelial cells of endometrial blood vessels consistent with hypertrophy and hyperplasia, and enlargement of arterioles and capillaries.3

Humans have 3 relaxin genes, designated relaxin-1, -2, and -3.4 Rats and mice each have 2 relaxin genes designated relaxin-1 and -3. Human relaxin-2, as well as rat and mouse relaxin-1 gene products, are true orthologs, insofar as they are secreted by the corpus luteum during pregnancy and circulate. Humans, rats, and mice have 1 relaxin receptor, the LGR7 (leucine rich repeat-containing G protein coupled) receptor recently renamed relaxin/insulin-like family peptide 1 receptor, RXFP1. Although human relaxin may also bind to the LGR8 receptor (RXFP2), albeit with reduced affinity,5 the preferred ligand for RXFP2 is insulin-like 3 (INSL3). Recently, 2 new receptors have been described for relaxin-3, GPCR135 and 142,6 although GPCR142 is a pseudogene in rats.

Infusion of recombinant human relaxin-2 (rhRLX) in nonpregnant conscious female and male rats significantly decreases renal and systemic vascular resistances, and increases cardiac output, renal blood flow, glomerular filtration, and global arterial compliance, thus mimicking the circulatory changes of pregnancy.1 Conversely, administration of relaxin-neutralizing antibodies or ovariectomy inhibits the circulatory changes during midterm pregnancy in conscious rats.1 In addition to changes in arterial tone and remodeling, another potential mechanism for the decrease in systemic vascular resistance and increase in global arterial compliance observed during relaxin administration or in pregnancy is maternal angiogenesis.7 Because BM-derived endothelial cells (BMDECs) can contribute to these processes,8 and circulating BMDECs and relaxin are both increased during normal pregnancy,4,9,10 we hypothesized that the gestational effects of relaxin on sustained virologic response and global arterial compliance could in part be mediated by BMDECs. In this study, we begin to address this overarching hypothesis by investigating whether relaxin can affect circulating BMDEC numbers and function using mouse and human BMDECs, as well as an in vivo model of angiogenesis.

Methods

Reagents

All tissue culture reagents were obtained from Invitrogen and MediaTech. Stromal-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) and MK-2206 were obtained from R&D Systems and Selleck Chemicals, respectively. Recombinant human (rh)relaxin was a generous gift from Corthera. B-R13/17K H2 was kindly provided by Dr John D. Wade (Howard Florey Institute, Melbourne, Australia). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise indicated.

Isolation of CD34+ BMDECs

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Florida, and written, informed consent was obtained from each subject in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Blood was collected from healthy controls by routine venipuncture into cell preparation tube with heparin (BD Biosciences), centrifuged at room temperature in a swinging bucket rotor for 20 minutes at 1800g, the PBMCs diluted with PBS supplemented with 2mM EDTA (PBSE) and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 300g. After washing the cell pellet, centrifugation was repeated. A total of 3.3 × 107 PBMCs were resuspended in 100 μL of PBSE to which 33 μL of FcR-blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec) and 33 μL of magnetic microbeads conjugated with an anti-CD34 antibody was added. After incubation for 30 minutes at 4°C, the cells were diluted in 10 times the volume of PBSE supplemented with 0.1% BSA, and CD34+ BMDECs were positively selected using automated magnetic selection autoMACS (Miltenyi Biotec). The selected cells were confirmed to be CD34+ BMDECs by costaining with PE-conjugated anti-CD34 (Miltenyi Biotec) and FITC-conjugated anti-CD45.

SDF-1/relaxin-induced chemotaxis

CD34+ BMDECs chemotaxis was carried out by staining the cells with calcein-AM (Invitrogen) before loading them into a Boyden Chamber. SDF-1 or rhRLX was loaded in the bottom chamber, which was overlaid with a polycarbonate membrane (8-μm pores; Neuro Probe) coated with 10% bovine collagen, and the cells were introduced into the top chamber. After 4.5 hours at 5% CO2 at 37°C, the percentage of cells that migrated was determined by collecting the media in the lower chamber and determining the relative fluorescence using a Synergy HT (Bio-Tek Instruments) with an excitation of 485 ± 20 nm and an emission of 528 ± 20 nm. For chemokinesis experiments, rhRLX was also added to the top chamber with the cells. Migration was done in RPMI except in experiments with L-NAME when EGM-2 (Lonza Switzerland) media was used.

Detection of NO produced by cells

CD34+ BMDECs or mouse BMDEC colonies were cultured on a 35-mm dish with a glass-bottom insert (MatTek). Bioavailable NO was determined as previously described.11 Briefly, BMDECs were incubated with 5μM 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluzorofluorescein (DAF-FM) diacetate (Invitrogen) for 30 minutes at 37°C in the dark. Excess extracellular probe was removed by washing in HBSS followed by incubation for 10 minutes at room temperature to allow for probe de-esterification. DAF-FM fluorescence increases by approximately 160-fold when it reacts with NO. Green fluorescence was measured in 20 to 30 cells per field in at least 6 fields per well from images captured as described in “Image acquisition and preparation.”

Mouse protocols

All animal procedures were performed according to protocols approved from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and complied with the standard laboratory animal procedures. Male Rxfp1−/− mice approximately 15 months of age12 and Rxfp2−/− mice 4 to 8 months of age,13 and their respective C57BL/6J and FVB wild-type littermates, as well as female C57BL/6J mice (the majority of which were 2-4 months of age) from Harlan were used.

Chimeric GFP mice were generated as previously described.14 Briefly, GFP transgenic mice (C57BL/6J background), obtained from The Jackson Laboratory, express GFP in every cell driven by chicken β-actin promoter and cytomegalovirus intermediate early enhancer. Wild-type C57BL/6J mice were irradiated with 950 rads and injected with BM cells (1 × 106) from GFP mice into the retro-orbital sinus. Chimeric mice were allowed to stably engraft for 6 to 10 months before subcutaneous injection of the Matrigel pellets. The mice were housed under standard conditions (12:12 light/dark cycle) with access to PROLAB RMH 2000 feed containing 0.32% sodium (PME Feeds) and water ad libitum.

Osmotic pump implantation

Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane using a portable anesthesia machine (Summit Medical). Alzet osmotic pumps (model 1007D 7-day infusion, or 1002 14-day infusion, Durect) containing rhRLX or vehicle (20mM sodium carbonate, pH 5.2) was then implanted subcutaneously on the back. The rate of infusion of rhRLX was 1 μg/hour. This yielded an average circulating concentration of 39.6 ± 4.1 ng/mL as determined by ELISA.

Mouse BMDEC enumeration

After 5 days of rhRLX or vehicle administration, the mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital and the whole peripheral blood was collected via cardiac perfusion with 2 to 3 mL heparin solution in saline (100 IU/mL).15 Blood collected from the mouse was layered onto Ficoll 400 and centrifuged at 400g for 30 minutes at 10°C. The buffy coat was collected, washed twice in PBS/2% FBS, resuspended in 3 mL Endocult Media (Stem Cell Technologies), and plated onto a 60-mm tissue culture plates coated with fibronectin and containing 3 mL of EGM-2. After 5 to 7 days, the number of colony-forming units were counted. They were identified as BMDECs based on their ability to stain with 1,1′-dioetadeeyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarboeyanine perchlorate acetylated low-density lipoprotein (DiI-AcLDL; Invitrogen) and Ulex europaeus 1 (Sigma-Aldrich).

Flow cytometry

A total of 3 mL of RBC lysis buffer (BD Biosciences PharMingen) was added to 20 μL of heparinized peripheral blood and, after 15 minutes in the dark, was centrifuged at 300g for 10 minutes, the supernate decanted, and cells resuspended in 100 μL of PBS. The antibodies PerCP anti–mouse Ly-6A/E (Sca-1; clone D7, BioLegend), PE anti–mouse CD117 (c-Kit; clone 2B8, BioLegend), and APC Mouse Lineage Antibody Cocktail (BD Biosciences) were added to the cells and incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature. The cells were washed with 2 to 3 mL of PBS, centrifuged at 300g for 10 minutes, and supernatant decanted. After resuspending in 300 μL of PBS/1%BSA/0.01% NaN3 and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, the cells were analyzed by FACSCaliber (BD Biosciences). Control staining with isotype-matched antibodies was carried out in parallel. Data analysis was performed using FCS Express Version 3.0 (De Novo Software).

Isolation of BM cells from mice

Mice were killed with pentobarbital, the femurs and tibias removed and placed in a 35-mm dish (on ice), and the bones sterilized with 70% ethanol for 20 seconds. After cutting the ends of both bones off with microsurgical scissors, the medullary cavities were flushed with PBS with a syringe with a 25-G 5/8” needle. To remove bits of bone and tissue clumps, the PBS containing the marrow was filtered through a sterile 40-μm nylon mesh (BD Biosciences), collected into a 15-mL of medium, and the cells centrifuged at 300g for 15 minutes at room temperature. The cells were washed twice with PBS/2% FBS, resuspended in EGM-2 medium (Lonza Switzerland), and plated onto a 60-mm tissue culture plate coated with fibronectin.

Plasma relaxin concentration

Plasma rhRLX concentrations were measured in duplicate using a commercially available ELISA that has been validated for mouse plasma (R&D Systems). The assay typically yielded a standard curve with R2 = 0.998 with a minimum detectable dose of less than 10 pg/mL. The intra-assay precision (average coefficient of variation of the unknowns) was less than 6.7% ± 1.3% and the interassay precision (average of coefficient of variation of the standards was 6.5% ± 2.1%. Plasma H2 relaxin was below the minimum detectable dose in vehicle-treated mice.

In vivo neoangiogenesis assay

Two 250-μL Matrigel implants were injected into each mouse: one injection containing 100 ng/mL relaxin and the other containing vehicle. Subcutaneous injections were made on the right (relaxin pellet) and left (vehicle pellet) sides of the midventral abdominal region. Seven days after injections, mice were anesthetized, perfused with saline and heparin, and blood was collected from the heart. After the blood was collected, the mice were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde and the Matrigel pellets were removed from the abdomen, placed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and stored at 4°C for 12 to 24 hours. The pellets were then washed 3 times with 1 times PBS, paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with anti-GFP and anti–MECA-32 antibodies. Average area of fluorescent cells was calculated from 3 fields per slide and 3 slides per pellet by summing all areas of fluorescence divided by total area analyzed from images captured as described in “Image acquisition and preparation.”

Image acquisition and preparation

Images were taken using an Axiovert 200 inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss), unless otherwise indicated. For image acquisition and analysis of fluorescence intensity of DAF-FM diacetate and for live imaging of NO in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) without Calcium, Magnesium, Phenol Red, we used the LD Achroplan 40×/0.60 Corr objective (Carl Zeiss), the AxioCam MRm charge-coupled device camera (CCD; Carl Zeiss), FITC filter (excitation 480/30 nm, emission 535/40 nm), and AxioVision (Version 4.5) image acquisition and analysis software. All optical filters were obtained from Chroma Technologies. The imaging of EPC colonies was done in the same fashion except with an A-Plan X10 objective (Carl Zeiss) was used.

Examination of neoangeogenesis of the implanted matrigel pellets was performed using an Axioplan 2 imaging system (Carl Zeiss) under Plan-Apochromat 10×/0.45 objective. The microscope was equipped with AxioCam MRm camera (CCD; Carl Zeiss) and image acquisition and analysis software Axio Vision (Version 4.5). Sections were additionally examined with a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM; 510 UV, Carl Zeiss). Images were acquired with a Plan-Neofluor 20X (N.A. = 0.75) and Plan-Fluor 63X oil (N.A. = 1.4) objectives and evaluated with Zeiss LSM 510 imaging software including 3D reconstruction. We used Adobe Photoshop CS4 for subsequent image editing and assembling of the figures.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was carried out using Student t test, Mann-Whitney rank-sum test, or 1-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons performed by the Holm-Sidak or Dunn method.

Results

Relaxin is a chemoattractant for human CD34+ BMDECs

To revisit the rationale: (1) circulating BMDEC numbers9,10 and relaxin4 increase during pregnancy; (2) relaxin contributes to the gestational decrease in systemic vascular resistance and increase in cardiac output and global arterial compliance at least in the gravid rat model1; and (3) maternal angiogenesis (perhaps mediated in part by BMDECs) may contribute to the cardiovascular adaptations observed in pregnancy.1,7 Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that relaxin can increase circulating BMDEC number, as well as BMDEC function (ie, migration and NO production). We used CD34 as a marker of progenitor populations, including BMDECs, that promote angiogenesis and take part in neovascularization because functional studies performed using purified BMDECs (the very rare CD34+/CD45−/VEGFR2+ or CD133+/CD45−/VEGFR2+ cells) would require a prohibitively large amount of blood.

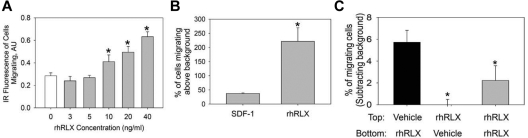

CD34+ BMDECs isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy volunteers migrated in response to increasing concentrations of rhRLX with a threshold dose of 10 ng/mL (P < .001 vs 0 ng/mL, Figure 1A). CD34+ BMDECs isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy volunteers migrated in response to rhRLX to a greater extent than to SDF-1, a major chemokine for CD34+ cells (Figure 1B). This stimulation of migration was not a chemokinetic effect because rhRLX added to the top well or both wells of the Boyden chamber did not increase migration (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Relaxin is a chemoattractant for CD34+ BMDEC migration. (A) CD34+ BMDECs migrate to increasing concentrations of rhRLX. *P < .001 versus 0 ng/mL rhRLX. Bar represents the mean (± SD) infrared (IR) fluorescence of migrating cells from 4 wells per rhRLX concentration. Shown is a representative of 4 experiments. (B) CD34+ BMDECs from 10 healthy persons that migrate to rhRLX (50 ng/mL) and SDF-1 (100nM) expressed as mean percentage (± SD) of cells in the lower chamber, above background migration. *P < .029 versus SDF-1. (C) CD34+ BMDECs were seeded in the upper Boyden chamber with either vehicle or 60 ng/mL of rhRLX in the top and/or bottom as indicated. Shown is mean percentage (± SD) of 3 wells of CD34+ BMDECs loaded to the top chamber that have migrated, after subtracting background. *P < .025 versus black bar.

Relaxin stimulates NO in human CD34+ BMDECs via PI3K/Akt

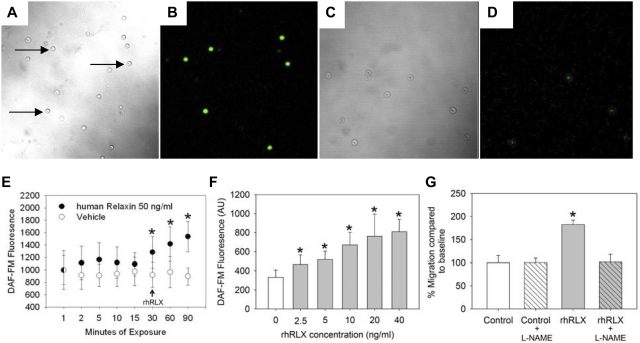

Previously, NO has been shown to be critical to BMDEC function16; we thus tested whether relaxin increased BMDEC NO levels using a method of single-cell fluorescence to measure bioavailable NO within individual cells17 (Figure 2A-D). Incubation with rhRLX leads to a rapid increase in intracellular NO concentrations (Figure 2E) with a threshold as low as 2.5 ng/mL rhRLX (Figure 2F). To determine whether stimulation of NO underlies the chemotactic effect of relaxin on BMDECs, we inhibited NOS with 10μM of the arginine analog L-NAME, a low concentration that does not lower basal levels of NO but effectively blocks agonist-induced increases in NO.18 The ability of relaxin to stimulate chemotaxis was blocked by low-level L-NAME, but importantly the basal level of migration was unaffected by these low levels of L-NAME (Figure 2G).

Figure 2.

CD34+ BMDECs produce NO in response to rhRLX. Human CD34+ BMDECs were isolated in the absence (A-B) and presence (C-D) of 100μM L-NAME and then incubated with DAF-FM before imaging by confocal microscopy. Panels A and C are brightfield images of panels B and D, respectively, the same fields imaged with 495 nm excitation and 515 nm emission. Arrows indicate some of the CD34+ BMDECs. Original magnification ×200. (E) CD34+ BMDECs were isolated from a healthy volunteer and labeled with DAF-FM for 30 minutes before removing probe and waiting 10 minutes for de-esterification. The cells were monitored for 30 minutes, to confirm a stable baseline of bioavailable NO before vehicle (○; arrow) or 50 ng/mL of rhRLX (●; arrow) was added to the CD34+ cells. Shown is the mean fluorescence (± SD) of at least 8 cells in which fluorescence was continuously monitored. *P < .01 versus last baseline value. (F) BMDEC-CFU were isolated from a healthy volunteer and labeled with DAF-FM. After 30 minutes to stabilize NO baseline, the indicated concentration of rhRLX was added and after 30 minutes fluorescence was determined. Data are mean ± SD. *P < .001 versus 0 ng/mL of rhRLX. (G) Cells were incubated with 10μM L-NAME before being placed in the Boyden chamber with 50 ng/mL of rhRLX. The mean percentage (± SD) of fluorescence of cells migrating relative to control is shown. *P < .001 versus all other treatments.

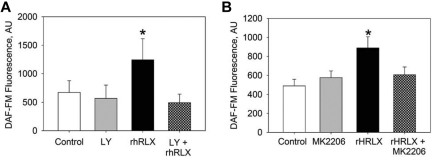

We previously demonstrated that the PI3K/Akt pathway is crucial to the rapid production of NO by endothelial cells and, as a consequence, rapid relaxation of small arteries.19 Thus, we used the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 to interrogate the role of PI3K in rhRLX-stimulated NO production in BMDECs. Pretreatment with LY294002 blocked rhRLX-stimulated increase in NO by CD34+ (Figure 3A). In addition, pretreatment with the Akt inhibitor MK220620 also prevented rhRLX stimulation of NO in BMDECs (Figure 3B). Taken together, these results suggest that the PI3K/Akt pathway is integral to relaxin-stimulated NO in CD34+ BMDECs.

Figure 3.

Relaxin stimulates NO production via PI3K/Akt. (A) Human CD34+ BMDECs were isolated from a healthy volunteer and pretreated with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (10μM) for 30 minutes as indicated before the addition of DAF-FM and continued incubation with LY294002 (LY). After 30 minutes of monitoring to confirm that bioavailable NO was stable, either vehicle (Control) or 100 ng/mL of rhRLX was added to the CD34+ BMDECs, and NO was measured again after 30 minutes. Fluorescence was determined for each condition in at least 30 cells within 2 separate wells. Data are mean ± SD. *P < .001 versus all other conditions. (B) CD34+ BMDECs were isolated from a healthy volunteer and pretreated with the Akt inhibitor MK2206 (20nM) for 30 minutes as indicated before the addition of DAF-FM and continued incubation with MK2206. After 30 minutes of monitoring, to confirm that bioavailable NO was stable, either vehicle (Control) or 50 ng/mL of rhRLX was added to the CD34+ BMDECs, and NO was measured again after 30 minutes. Fluorescence was determined for each condition in 2 wells for at least 30 cells per well. Data are mean ± SD. *P < .001 versus control. There is a significant difference between control and MK2206 (P = .025) but no difference between MK2206 and MK2206 + rhRLX-treated cells.

Relaxin increases circulating mouse BMDECs in vivo

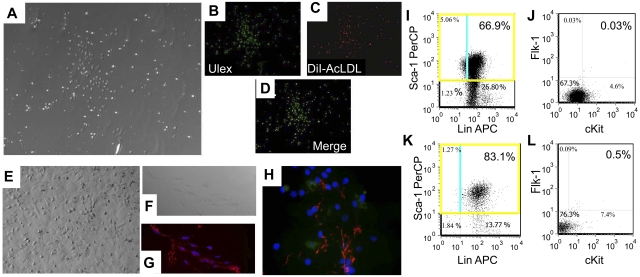

The effect of relaxin on circulating BMDECs in vivo was assessed by 2 different methods: (1) BMDEC colony assay; and (2) FACS analysis by determining the percentage of Sca+, Flk+, cKit+ cells in the peripheral blood.21 In the BMDEC colony assay, endothelial colonies from the peripheral blood that stain with Ulex europaeus 1 and DiI-AcLDL can be seen after 1 week in culture (Figure 4A-D). These colonies can be continuously cultured for more than 3 months when they take on a more endothelial appearance (Figure 4E) and express VWF and MECA-32 (Figure 4F-G), thus confirming their endothelial progenitor phenotype. Using the BMDEC colony assay, mice implanted with osmotic pumps containing rhRLX (n = 9 mice) had almost 2-fold more colony-forming units versus the vehicle-infused group (n = 9 mice; 14.6 ± 4.0 vs 7.8 ± 1.4 CFU/mice, respectively; P = .022).

Figure 4.

Relaxin increases circulating BMDECs in mice by colony assay and flow cytometry. (A) BMDEC-CFU stimulated by relaxin have characteristics of late outgrowth colonies. BMDEC-CFU are counted after 5 days of culture, and a brightfield view of colonies is shown (original magnification ×100). (B) True BMDEC-CFUs demonstrate Ulex europaeus 1 staining (original magnification ×200). (C) DiI-AcLDL uptake (original magnification ×200). (D) Dual staining in a merged image of Ulex and DiI-AcLDL staining (original magnification ×200). Instead of staining, the BMDEC-CFU cells can be propagated for months. (E) Brightfield view of cells after 3 months of propagation taking on a cobblestone, endothelial, monolayer appearance. (F) Brightfield view of propagated cells that were trypsinized and plated onto a coverslip for immunostaining with anti–VWF and/or anti–MECA-32. (G) Merged image of cells in panel F stained with anti-VWF (red) and the nuclear stain DAPI (blue; original magnification ×400). (H) Merged image of another coverslip stained with anti-VWF (red), anti–MECA-32 (green), and the nuclear stain DAPI (blue; original magnification ×630). (I-K) Mice were implanted with a osmotic pumps pump containing vehicle (I-J) or rhRLX (K-L), and after 5 days the peripheral blood was collected and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibody to mouse endothelial cell markers Lin, Sca1, cKit, and Flk1. The gated cells were analyzed for Sca-1 and Lin characteristics (I,K), and the subpopulation of Sca1+ cells was analyzed for Flk1 and cKit expression (J,L). Background staining was corrected by use of isotype controls for all markers. Percentages shown are percent of gated cells, not total lymphocytes.

We next confirmed the effect of relaxin on BMDEC number by flow cytometry. Using the same rhRLX and vehicle treatment regimens, the number of Sca+, Flk+, cKit+ cells was determined. In mice treated with vehicle and rhRLX (n = 15 each), 0.002% ± 0.0001% and 0.032% ± 0.0005% of total lymphocytes were Sca+, Flk+, cKit+, respectively (P = .013). Representative FACS analyses are shown in Figure 4I-L.

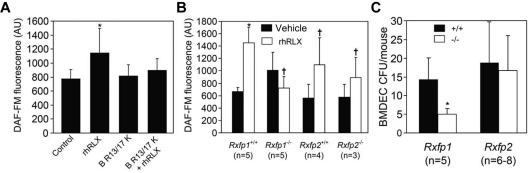

Relaxin-induced BMDEC mobilization and NO stimulation are mediated by the RXFP1 relaxin receptor

Relaxin increases CD34+ BMDEC NO production and migration in vitro and mobilizes BMDECs in vivo. To determine which of the RXFP receptors may mediate these effects of relaxin on BMDECs, we tested the newly developed human relaxin-2 antagonist, B-R13/17K H2.22 This heterodimeric peptide antagonist inhibited the increase in NO in response to rhRLX treatment (Figure 5A), consistent with a role for the RXFP1 receptor in mediating NO production by rhRLX.

Figure 5.

Relaxin activates BMDECs through the RXFP1 relaxin receptor. (A) The peptide B-R13/17K H2 (H2), a relaxin antagonist, was added as indicated to CD34+ BMDECs at a concentration of 1μM in the presence or absence of rhRLX (50 ng/mL). Shown is the DAF-FM fluorescence in arbitrary units (± SD) of 2 wells, 20 cells per well. *P < .002 versus all other treatments. Shown is a representative of 3 experiments. (B) BMDECs were isolated from the BM of wild-type littermates and Rxfp1 or Rxfp2 knockout mice and treated with vehicle (black bars) or rhRLX 50 ng/mL (white bars) for 10 minutes before the determining intracellular bioavailable NO by DAF-FM. The NO fluorescence from at least 20 cells was analyzed for each mouse. Shown is the mean DAF-FM fluorescence in arbitrary units (± SD). *P < .009 versus vehicle treated cells. †P < .05 versus untreated cells. n indicates the number of mice studied. (C) Wild-type (+/+) littermates and Rxfp1 and Rxfp2 knockout (−/−) mice were implanted with osmotic pumps containing rhRLX, and after 5 days their blood was collected and BMDEC-CFU were determined. Shown is the number of BMDECs (± SD). *P < .01 versus Rxfp1+/+. n indicates the number of mice studied.

To determine whether the RXFP1 receptor is responsible for mediating the effect of relaxin on BMDEC mobilization, we used Rxfp1 and Rxfp2 knockout mice. BM cells isolated from the Rxfp2 knockout and FVB wild-type littermates both showed a significant increase in NO in response to rhRLX (Figure 5B). However, BM cells from Rxfp1 knockout mice failed to demonstrate an increase in NO when treated with rhRLX in contrast to the C57BL/6J wild-type littermates (Figure 5B).

Consistent with these findings, infusion of rhRLX by osmotic pump led to an increase in circulating BMDEC-CFU in both Rxfp2 knockout and wild-type littermates (Figure 5C), whereas there were significantly less circulating BMDEC-CFU in rhRLX-infused Rxfp1 knockout mice versus their wild-type counterparts (Figure 5C). All wild-type and knockout mice treated with vehicle had comparable number of BMDECs-CFU (data not shown).

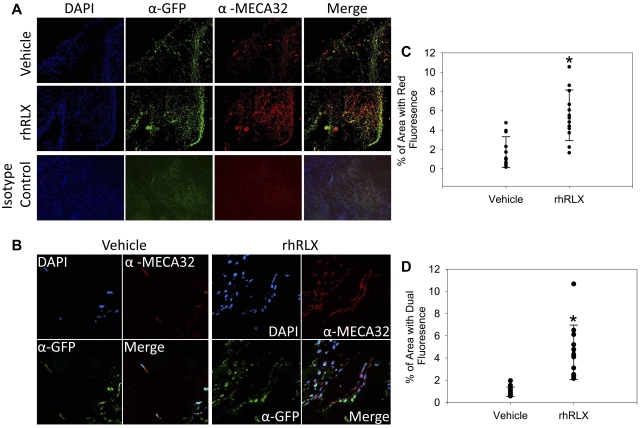

Relaxin stimulates vasculogenesis in vivo

To test whether relaxin will stimulate angiogenesis and enhance recruitment of BMDECs into sites of angiogenesis, we inserted Matrigel pellets containing rhRLX or its vehicle subcutaneously in GFP chimeric mice, in which BM cells and cells derived from the BM exclusively express GFP. Representative epifluorescent and confocal images are shown in Figures 6A and B, respectively. Pellets impregnated with rhRLX demonstrated a 3.2-fold increase in the mean area of red fluorescence (pan-endothelial cell antigen, α- MECA-32) versus pellets containing vehicle (mean area 5.5% ± 4.2% vs 1.7% ± 0.84%, respectively, P < .001, Figure 6C), indicating that rhRLX stimulated angiogenesis. Of note, pellets that contained rhRLX showed a 4.5-fold increase in the mean area of dual fluorescent areas: cells expressing both GFP and α-MECA-32 (4.5% ± 4.2% vs 0.99% ± 0.84%, respectively, P = .001, Figure 6D), indicating an increase in the number of cells derived from the BM that differentiated into endothelial cells (Figure 6A). Confocal imaging demonstrated blood vessels lined with GFP+ BMDECs (Figure 6B), although the different cell localization of the GFP (intracellular) and MECA-32 (cell surface) precluded detection of yellow in the merged image by confocal microscopy.

Figure 6.

Relaxin recruits BMDECs into areas of neovascularization. (A) Chimeric mice (wild-type mice with GFP BM) were implanted with Matrigel pellets impregnated with vehicle or rhRLX, as indicated, and after 7 days the pellets were isolated, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with DAPI, a pan-endothelial cell antigen monoclonal antibody MECA-32, anti-GFP, or isotype control antibodies as indicated and imaged using conventional fluorescent microscopy. (B) Same as panel A, except that slides were imaged using confocal microscopy. (C) Percentage of area that fluoresces red (by epifluorescence) indicating MECA-32 staining. Shown is average area of 3 fields from 6 different sections from 9 pellets for each treatment. *P < .001 by paired t test. (D) Percentage of area that expresses dual fluorescence (by epifluorescence) indicating dual MECA-32 and GFP staining. Shown is average area of 3 fields from 6 different sections from 9 pellets. *P < .001 by paired t test.

Discussion

The major new finding of this work is that the pregnancy hormone, relaxin, regulates the biology of BM derived endothelial cells in several ways: (1) relaxin increases intracellular NO in BMDECs; (2) the hormone is a chemoattractant for the cells; (3) it mobilizes BMDECs into the circulation; and (4) it enhances their integration into sites of vasculogenesis. In addition, these effects of relaxin are mediated by the major relaxin receptor, RXFP1, and not the RXFP2 receptor. Finally, these findings were derived from both mouse and human studies.

Unemori et al previously reported enhanced vessel in-growth of Matrigel plugs containing rhRLX that were implanted subcutaneously in rodents.23 However, their study did not delineate the potential contribution of BMDECs. In contrast, our results clearly show that rhRLX stimulated integration of BMDECs into sites of vasculogenesis using the same model because GFP+ BM cells were detected in the blood vessel walls and many costained for a mature endothelial marker (Figure 6). In the same report, Unemori et al also demonstrated enhanced blood vessel growth in response to circulating rhRLX using the Hunt-Schilling wound chamber.23 It will be important for us in future studies to adopt this methodology in GFP chimeric mice, to demonstrate the contribution of BMDECs to vasculogenesis in response to circulating rhRLX.

Relaxin is a peptide hormone emanating from the corpus luteum that circulates at low levels in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle (∼ 100 pg/mL) and peaks during the first trimester of pregnancy (∼ 1.0 ng/mL) falling to intermediate levels thereafter (∼ 0.5 ng/mL).4 Although the level of relaxin during human pregnancy ranges from 0.5 to 1 ng/mL, the majority of the experiments performed herein used rhRLX in the 10- to 30-ng/mL range, although an rhRLX concentration as low as 2.5 ng/mL significantly increased NO production by human BMDECs (Figure 2). In mice, the higher levels are the best estimate of early to midterm pregnancy concentrations based on extrapolating from 2 studies.24,25 In addition, concentrations of 10 to 40 ng/mL produced significant changes in hemodynamics during the phase 1 and 2 trials of relaxin in heart failure,26 and another goal of the present work is to evaluate relaxin as a potential therapeutic agent via its actions on BMDECs.

Previously, relaxin was shown to augment MCP-1–induced monocyte chemotaxis but was not a monocyte chemoattractant by itself.27 The chemokinetic effect on monocytes was dose-dependent and in proportion to relaxin-induced cAMP accumulation.27 In this study, we demonstrate that relaxin is a chemoattractant, but not chemokinetic agent, increasing directional CD34+ BMDEC migration in a NO-dependent manner (Figure 1).

Relaxin is emerging as a major player in the maternal hemodynamic alterations that occur during normal pregnancy: decrease in systemic and renal vascular resistances with reciprocal increases in cardiac output, renal blood flow, and in glomerular filtration rate.1 In addition, the hormone can increase arterial compliance.28 Our overarching hypothesis, is that relaxin contributes to maternal angiogenesis during pregnancy, in part by mobilizing, activating, and incorporating BMDECs into sites of vasculogenesis. In turn, maternal angiogenesis and vasculogenesis abet the profound gestational decrease in systemic vascular resistance and increase in global arterial compliance. We are currently investigating a role for BMDECs in these physiologic adaptations to pregnancy.

BMDECs integrate into the vascular wall either differentiating into endothelial cells (vasculogenesis) or serving a paracrine role in stimulating local angiogenesis or endothelial repair. Of note is that the number of CD34+ BMDECs expressing VEGFR-2 that circulate in the bloodstream is an independent predictor of early subclinical atherosclerosis in healthy subjects,29 inversely proportional to the risk factors for atherosclerosis,30 and predicts future cardiovascular events.31 Although there may be some need for enhancing endothelial repair because of endothelial injury because of a systemic inflammatory response32 and hemodynamic mechanical stresses, which accompany normal gestation, another possibility is that, in addition to maternal angiogenesis, placental and fetal angiogenesis is also abetted by circulating maternal BMDECs during pregnancy. Indeed, fetal endothelial progenitor cells contribute to maternal angiogenesis during pregnancy.33 Moreover, it is also possible that BMDECs participate in uterine vascular remodeling during gestation. Robb et al hypothesized that because BMDECs may have a homeostatic role in maintaining both the maternal systemic and uterine vasculature, BMDECs may be the link between preexisting cardiovascular risk factors in women, and their increased risk of preeclampsia.34

Several studies have indirectly addressed the role of circulating BMDECs in postnatal vasculogenesis.35 Pregnancy is clearly associated with marked angiogenesis in the fetus and placenta, but presumably in the mother as well. For example, the accretion of maternal fat,36 expansion of mammary tissue,37 and B-cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia38 during pregnancy all necessitate the formation of new blood vessels, and there are probably other sites of maternal neovascularization yet to be delineated. In the mouse, sprouting angiogenesis occurring in the first third of pregnancy is one mechanism for the capillary expansion in mammary tissue.37 In addition, optimal uterine implantation and subsequent placentation require robust endometrial vascular development,39 and relaxin has been implicated in this process.3,40,41 Angiogenesis plays such a critical role in implantation that a single dose of an anti–angiogenic compound (AGM-1470) administered before or shortly after implantation will result in resorption of all embryos in mice.42 In humans, umbilical blood flow velocity, as measured by Doppler ultrasound, increases and resistance decreases throughout the last half of gestation,43 in part reflecting the formation of new blood vessels. Embryonic death and blighted ova have been demonstrated to occur when chorionic villous vascularization is deficient44 and increased uterine vascular resistance and reduced uterine blood flow are predictors of high-risk pregnancies.45 Thus, the role of maternal BMDECs in all of these processes requiring new blood vessel formation or remodeling clearly needs investigation.

The findings herein also provide potential mechanistic insights into the impaired reduction in systemic vascular resistance and increase in global arterial compliance that occurs in preeclampsia46 or in pregnant women with diabetes.47 Although not all studies are in agreement, decreased circulating BMDECs have been reported in preeclampsia.9,48 Similarly, the number of circulating BMDECs in patients with both type I (quantified by CFU) and type II (CD34+, VEGFR2+ cells measured by flow cytometry) diabetes is significantly reduced compared with healthy subjects.49 Thus, a defect in the number and function of BMDECs may in part be responsible for the lack of reduction in systemic vascular resistance and increase in global arterial compliance in preeclamptic and diabetic pregnancies.46,47

In conclusion, another potentially novel feature of relaxin is its ability to mobilize and activate BMDECs without being pro-inflammatory; indeed, the hormone may be anti-inflammatory.50 This would make relaxin the only cytokine known to positively impact BMDECs number and function without being pro-inflammatory, which may offer a distinct advantage for relaxin as a potent therapeutic in cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr Agustin Barbara for technical assistance.

This work was supported by Gatorade Research (M.S.S.), National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL067937 (K.P.C.), R01 HD037067 (A.I.A.), and R01 EY12601 and EY07739 (M.B.G.).

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: M.S.S. designed the research, analyzed the data, interpreted the data, and prepared the manuscript; L.S. performed the research and analyzed the data; S.L. and Y.P.D. performed the research; A.I.A. supplied the knockout mice; J.K. performed an experiment; J.T.M. performed experiments, analyzed the data, and helped prepare the manuscript; M.B.G. designed an experiment and prepared the manuscript; and K.P.C. designed the research, interpreted the data, and prepared the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.P.C. and M.S.S. hold and/or have submitted patents for relaxin. K.P.C. received honoraria from the pharmaceutical industry for consultation on relaxin. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mark S. Segal, PO Box 100224, Gainesville, FL, 32610-0267; e-mail: segalms@medicine.ufl.edu.

References

- 1.Conrad KP. Emerging role of relaxin in the maternal adaptations to normal pregnancy: implications for preeclampsia. Semin Nephrol. 2011;31(1):15–32. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hisaw F. Experimental relaxation of the public ligament of the guinea pig. Proc Exp Biol Med. 1926;23:661–663. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hisaw FL, Hisaw FL, Jr, Dawson AB. Effects of relaxin on the endothelium of endometrial blood vessels in monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Endocrinology. 1967;81(2):375–385. doi: 10.1210/endo-81-2-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherwood O. Relaxin. New York, NY: Raven; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sudo S, Kumagai J, Nishi S, et al. H3 relaxin is a specific ligand for LGR7 and activates the receptor by interacting with both the ectodomain and the exoloop 2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(10):7855–7862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212457200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Kuei C, Sutton SW, et al. Pharmacological characterization of relaxin-3/INSL7 receptors GPCR135 and GPCR142 from different mammalian species. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312(1):83–95. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.073486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conrad KP, Debrah DO, Novak J, Danielson LA, Shroff SG. Relaxin modifies systemic arterial resistance and compliance in conscious, nonpregnant rats. Endocrinology. 2004;145(7):3289–3296. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, et al. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275(5302):964–966. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugawara J, Mitsui-Saito M, Hoshiai T, Hayashi C, Kimura Y, Okamura K. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells during human pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(3):1845–1848. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gussin HA, Bischoff FZ, Hoffman R, Elias S. Endothelial precursor cells in the peripheral blood of pregnant women. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2002;9(6):357–361. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(02)00188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah R, Beem E, Sautina L, Zharikov SI, Segal MS. Mitomycin- and calcineurin-associated HUS, endothelial dysfunction and endothelial repair: a new paradigm for the puzzle? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(2):617–620. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamat AA, Feng S, Bogatcheva NV, Truong A, Bishop CE, Agoulnik AI. Genetic targeting of relaxin and insulin-like factor 3 receptors in mice. Endocrinology. 2004;145(10):4712–4720. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorlov IP, Kamat A, Bogatcheva NV, et al. Mutations of the GREAT gene cause cryptorchidism. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(19):2309–2318. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.19.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diao Y, Guthrie S, Xia SL, et al. Long-term engraftment of bone marrow-derived cells in the intimal hyperplasia lesion of autologous vein grafts. Am J Pathol. 2008;172(3):839–848. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diao Y, Xue J, Segal MS. A novel mouse model of autologous venous graft intimal hyperplasia. J Surg Res. 2005;126(1):106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimmeler S, Dernbach E, Zeiher AM. Phosphorylation of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase at Ser-1177 is required for VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration. FEBS Lett. 2000;477(3):258–262. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01657-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sautina L, Sautin Y, Beem E, et al. Induction of nitric oxide by erythropoietin is mediated by the β common receptor and requires interaction with VEGF receptor 2. Blood. 2010;115(4):896–905. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-216432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schuler A, Sautina L, Zharikov S, et al. Philadelphia, PA: American Society of Nephrology; 2005. Epoetin alfa enhances chemotaxis of circulating endothelial progenitor cells to SDF-1 and stimulates intracellular nitric oxide production [abstract]. p. 48A. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGuane J, Debrah J, Sautina L, et al. Relaxin induces rapid dilation of rodent small renal and human subcutaneous arteries via PI3 kinase and nitric oxide. Endocrinology. 2011;152(7):2786–2796. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirai H, Sootome H, Nakatsuru Y, et al. MK-2206, an allosteric Akt inhibitor, enhances antitumor efficacy by standard chemotherapeutic agents or molecular targeted drugs in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(7):1956–1967. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemarie CA, Shbat L, Marchesi C, et al. Mthfr deficiency induces endothelial progenitor cell senescence via uncoupling of eNOS and downregulation of SIRT1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300(3):H745–H753. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00321.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hossain MA, Samuel CS, Binder C, et al. The chemically synthesized human relaxin-2 analog, B-R13/17K H2, is an RXFP1 antagonist. Amino Acids. 1994;39(2):409–416. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0454-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Unemori EN, Lewis M, Constant J, et al. Relaxin induces vascular endothelial growth factor expression and angiogenesis selectively at wound sites. Wound Repair Regen. 2000;8(5):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475x.2000.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherwood OD, Crnekovic VE, Gordon WL, Rutherford JE. Radioimmunoassay of relaxin throughout pregnancy and during parturition in the rat. Endocrinology. 1980;107(3):691–698. doi: 10.1210/endo-107-3-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Byrne EM, Steinetz BG. Radioimmunoassay (RIA) of relaxin in sera of various species using an antiserum to porcine relaxin. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1976;152(2):272–276. doi: 10.3181/00379727-152-39377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teerlink JR, Metra M, Felker GM, et al. Relaxin for the treatment of patients with acute heart failure (Pre-RELAX-AHF): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-finding phase IIb study. Lancet. 2009;373(9673):1429–1439. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60622-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Figueiredo KA, Mui AL, Nelson CC, Cox ME. Relaxin stimulates leukocyte adhesion and migration through a relaxin receptor LGR7-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(6):3030–3039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506665200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Debrah DO, Debrah JE, Haney JL, et al. Relaxin regulates vascular wall remodeling and passive mechanical properties in mice. J Appl Physiol. 2011;111:260–271. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00845.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fadini GP, Coracina A, Baesso I, et al. Peripheral blood CD34+KDR+ endothelial progenitor cells are determinants of subclinical atherosclerosis in a middle-aged general population. Stroke. 2006;37(9):2277–2282. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000236064.19293.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vasa M, Fichtlscherer S, Aicher A, et al. Number and migratory activity of circulating endothelial progenitor cells inversely correlate with risk factors for coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2001;89(1):e1–e7. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.093953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt-Lucke C, Rossig L, Fichtlscherer S, et al. Reduced number of circulating endothelial progenitor cells predicts future cardiovascular events: proof of concept for the clinical importance of endogenous vascular repair. Circulation. 2005;111(22):2981–2987. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.504340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Redman CW, Sargent IL. Immunology of pre-eclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63(6):534–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen Huu S, Oster M, Uzan S, Chareyre F, Aractingi S, Khosrotehrani K. Maternal neoangiogenesis during pregnancy partly derives from fetal endothelial progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(6):1871–1876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606490104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robb AO, Mills NL, Newby DE, Denison FC. Endothelial progenitor cells in pregnancy. Reproduction. 2007;133(1):1–9. doi: 10.1530/REP-06-0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crosby JR, Kaminski WE, Schatteman G, et al. Endothelial cells of hematopoietic origin make a significant contribution to adult blood vessel formation. Circ Res. 2000;87(9):728–730. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.9.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinoshita T, Itoh M. Longitudinal variance of fat mass deposition during pregnancy evaluated by ultrasonography: the ratio of visceral fat to subcutaneous fat in the abdomen. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;61(2):115–118. doi: 10.1159/000089456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Djonov V, Andres AC, Ziemiecki A. Vascular remodelling during the normal and malignant life cycle of the mammary gland. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;52(2):182–189. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20010115)52:2<182::AID-JEMT1004>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johansson M, Mattsson G, Andersson A, Jansson L, Carlsson PO. Islet endothelial cells and pancreatic beta-cell proliferation: studies in vitro and during pregnancy in adult rats. Endocrinology. 2006;147(5):2315–2324. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torry DS, Leavenworth J, Chang M, et al. Angiogenesis in implantation. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2007;24(7):303–315. doi: 10.1007/s10815-007-9152-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldsmith LT, Weiss G, Palejwala S, et al. Relaxin regulation of endometrial structure and function in the rhesus monkey. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(13):4685–4689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400776101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dallenbach-Hellweg G, Dawson AB, Hisaw FL. The effect of relaxin on the endometrium of monkeys: histological and histochemical studies. Am J Anat. 1966;119(1):61–77. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klauber N, Rohan RM, Flynn E, D'Amato RJ. Critical components of the female reproductive pathway are suppressed by the angiogenesis inhibitor AGM-1470. Nat Med. 1997;3(4):443–446. doi: 10.1038/nm0497-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gadelha Da Costa A, Mauad Filho F, Spara P, Barreto Gadelha E, Vieira Santana Netto P. Fetal hemodynamics evaluated by Doppler velocimetry in the second half of pregnancy. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2005;31(8):1023–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meegdes BH, Ingenhoes R, Peeters LL, Exalto N. Early pregnancy wastage: relationship between chorionic vascularization and embryonic development. Fertil Steril. 1988;49(2):216–220. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59704-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu CK, Smith GC, Papageorghiou AT, Cacho AM, Nicolaides KH. An integrated model for the prediction of pre-eclampsia using maternal factors and uterine artery Doppler velocimetry in unselected low-risk women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(1):330. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hibbard JU, Korcarz CE, Nendaz GG, Lindheimer MD, Lang RM, Shroff SG. The arterial system in pre-eclampsia and chronic hypertension with superimposed pre-eclampsia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;112(7):897–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Airaksinen KE, Ikaheimo MJ, Salmela PI, Kirkinen P, Linnaluoto MK, Takkunen JT. Impaired cardiac adjustment to pregnancy in type I diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1986;9(4):376–383. doi: 10.2337/diacare.9.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buemi M, Allegra A, D'Anna R, et al. Concentration of circulating endothelial progenitor cells (EPC) in normal pregnancy and in pregnant women with diabetes and hypertension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(1):e61–e66. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loomans CJM, de Koning EJP, Staal FJT, et al. Endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction: a novel concept in the pathogenesis of vascular complications of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53(1):195–199. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brecht A, Bartsch C, Baumann G, Stangl K, Dschietzig T. Relaxin inhibits early steps in vascular inflammation. Regul Pept. 2011;166(1):76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]