Abstract

Remarkably little is known about folliculogenesis in the dog. Objectives were to characterize (1) changes in follicle/oocyte diameter and granulosa cell number and (2) expression of Fibroblast Growth Factor -2 (FGF-2) and -7 (FGF-7) during ovarian follicle development in this species. Fourteen ovarian pairs were excised and processed for histological evaluation. Two to four serial sections/bitch were stained with hematoxylin, and follicle/oocyte diameters and granulosa cell number were determined at each developmental stage. Means follicle and oocyte size were compared among stages by ANOVA. Relationships between follicle diameter and oocyte size and granulosa cell number were determined using correlation and regression analysis, respectively. Another eight serial ovarian sections/bitch were processed for immuno-staining to determine FGF-2 and -7 expression. Primordial and primary follicles were similar in size (P < 0.05), but smaller than the progressively increasing (P < 0.05) diameters of later stage counterparts. Oocyte diameter gradually increased (P < 0.05) among oocytes derived from primordial, primary, secondary and early antral follicles with no difference (P > 0.05) thereafter. Oocyte size and granulosa cell number increased (P < 0.01) with follicular diameter. Except during anestrus, FGF-2 was detectable in oocytes and granulosa cells of primordial to secondary follicles. In adult bitches, FGF-7 was localized in granulosa cells of primary and secondary follicles and also occurred in the theca layer of antral follicles during proestrus and estrus. In summary, folliculogenesis in the domestic dog occurs in two phases with a preantral phase characterized by increasing follicle size in association with oocyte growth and granulosa cell proliferation. The subsequent antral phase is linked with marked granulosa cell proliferation and accumulation of antral cavity fluid. Finally, the temporal expression pattern of FGF-2 implies its role in follicular activation, whereas FGF-7 activities appear related to later folliculogenesis.

Introduction

For centuries, the domestic dog has served as a socially compatible companion species to humans (Patronek, 1994; Pennisi, 2002; O’Brien and Murphy, 2003). The dog also has been used for physiological and metabolic studies in biomedical research since the 17th century (Tsai et al., 2007) and, more recently, as a laboratory model for studying human genetic diseases and cancers (Patterson, 2000; Tsai et al., 2007). However, despite the value and commonality, this species continues to elude consistent, controlled reproduction either by natural or assisted breeding. This is mostly due to the lack of detailed information on dog reproductive biology, including on follicle and oocyte development.

Dog follicles generally have been categorized into five classes based on morphology, size, type/number of follicle cell layers and presence of follicular fluid: primordial, primary, secondary (also known as preantral), early antral and advanced antral (see review, Songsasen and Wildt, 2007). Primordial follicle formation occurs from 17 to 54 days after birth (Andersen and Simpson, 1973; Blackmore et al., 2004; Tesoriero, 1981) with each follicle of this type containing a small oocyte (~25 μm diameter) with a single layer of flattened granulosa cells (but no zona pellucida; ZP) (Durrant et al., 1998). By 120 days, each primary follicle contains a small, pale oocyte with a distinctive ZP and a single layer of cuboidal granulosa cells (Durrant et al., 1998; Barber et al., 2001). Secondary follicles have two or more layers of granulosa cells (Barber et al., 2001). Fully grown oocytes (>100 μm) with dark appearance (due to cytoplasmic lipid) can be observed in advanced (multi-layered) preantral follicles (Durrant et al., 1998). Early antral follicles are characterized by the formation of a fluid filled-cavity (Andersen and Simpson, 1973). Both preantral and early antral follicles can be observed initially in the ovarian cortex from 120 through 160 days after birth (Andersen and Simpson, 1973; Durrant et al., 1998; Blackmore et al., 2004). Thus, the recruitment interval from a primordial to early antral follicle requires a protracted 70 to 150 days in the prepubertal bitch. Advanced stage antral follicles (>2 mm diameter; also known as Graaffian follicles) can be found in bitches as young as 6 mo of age and shortly before proestrus (Wildt et al., 1977; England and Allen, 1989). Folliculogenesis has not been extensively studied in the adult dog. The only available information on duration of folliculogenesis in this age class is gleaned from a study in whole-body x-irradiated dogs, where the interval from the irradiation treatment to the first follicular maturation and ovulation were reported to be 110 and 170 days, respectively (Spanel-Borowski and Calvo, 1982).

Folliculogenesis is a highly organized process involving proliferation and differentiation of follicle cells. Follicular activation and development have been extensively documented in the mouse (Eppig, 2001; Demeestere, et al., 2005), cow (Driancort et al., 2000) and human (Picton, 2001; see reviews Knight and Glister, 2006; van den Hurk and Zhao, 2005). Several factors has been identified to play important roles in follicle activation and maturation, including oncogenes, the transforming growth factor superfamily, gonadotropins and gonadal hormones and growth hormone and factors (see review van den Hurk and Zhao, 2005). Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) family members, including FGF 2, -7 and -10 are potential paracrine signaling molecules regulating follicle development (van den Hurk and Zhao, 2005) . FGF-2 has been shown to play roles in final preovulatory follicle growth in the cow (Berisha et al., 2004) and is known to promote activation of primordial follicles and subsequent growth of cultured goat follicles (Matos et al., 2007a,b). The level of FGF-7 expression in bovine theca cells increases as follicle development progresses, suggesting that this growth factor plays a role in cell proliferation during folliculogenesis (Parrott and Skinner, 1998). FGF-10 also is detected in oocytes and somatic cells of preantral and antral cow follicles, with expression level associated with follicle health (Buratini et al., 2007).

Although a classification scheme has been described for the dog follicle (see review Songsasen and Wildt, 2007), there surprisingly is no published information on the temporal characteristics associated with follicle and oocyte growth and granulosa cell proliferation. Furthermore, the expression and localization of ovarian FGF has not been explored for this species. For the present study, we hypothesized that (1) oocyte growth and granulosa cell proliferation are linked to ovarian follicular development in the dog, and (2) FGF-2 and -7 are expressed in follicles, albeit at different phases of the folliculogenic process. The objectives were to (1) characterize and interrelate changes in follicle/oocyte diameter and granulosa cell number while (2) developing a beginning understanding of the significance of growth factors, specifically the localization of FGF-2 and -7 during various stages of follicle development.

Materials and Methods

Ovarian tissue collection

Fourteen ovarian pairs were recovered from bitches (11 breeds; age, 5 mo to 7 yr) undergoing routine ovariohysterectomy at local veterinary clinics. Based on morphological criteria (i.e., number and size of follicles/corpora lutea) and animal age, the reproductive cycle of bitches was classified as pre-pubertal (n = 4), proestrous (n = 3), estrous (n = 3) or anestrous (n = 2). Upon arrival at the laboratory at the Conservation & Research Center, ovaries were washed in Tissue Culture Medium 199 plus HEPES, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS or formalin solution and forwarded to a commercial laboratory (Histoserve, Germantown, MD) for histological sectioning (5 μm thick).

Histological processing and follicle identification

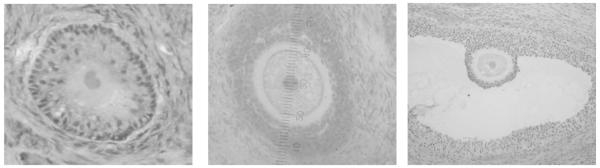

Histological sections of ovarian tissues were de-paraffinized in xylene, gradually hydrated through graded alcohol solutions (100-95-0%) and then stained with Gill’s formulation #2 hematoxylin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for follicle identification using light microscopy. Follicles were divided into five classes on the basis of morphology and number of follicular cells in the widest cross-section, as previous described (Songsasen and Wildt, 2007): 1) primordial (an oocyte without a zona pellucida [ZP] surrounded by a single layer of flattened granulosa cells; n = 16); 2) primary (oocyte with distinctive ZP surrounded by a single layer of cuboidal granulosa cells; n = 13); 3) secondary (oocyte surrounded by several layers of granulosa cells; n = 48); 4) early antral (space among granulosa cells or a segmented cavity with two or more compartments; n = 22); or 5) antral (one large, continuous cavity; n = 10) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Micrographs of dog (A) primordial, (B) primary, (C) secondary, (D) early antral and (D) antral follicles.

Follicle diameter and granulosa cell numbers

Two to four ovarian sections from each bitch were stained with hematoxylin as described above and evaluated under a light microscope equipped with an ocular micrometer (Olympus BX40, Olympus America Inc., Central Valley, PA). Diameter of the oocyte and its follicle were determined by averaging two measurements at the widest cross section of follicles that contained an oocyte nucleolus (Griffin et al., 2006). Follicles were measured from the outer wall of the theca cells (if present) or from the outer layer of the granulosa cells (when theca cells were absent). Oocytes were measured to exclude the ZP. Numbers of granulosa cells in each developmental stage were counted manually under light microscopy (40X).

FGF-2 and FGF-7 expression and localization

Eight serial ovarian sections from each bitch were processed for immuno-staining using polyclonal rabbit and goat antibodies against FGF-2 and -7, respectively (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) according to manufacturer’s directions. For each set, four sections were incubated with anti-growth factor antibodies and two with the primary antibody with the remainder serving as negative controls (primary antibody omitted). Localization of growth factors was visualized using bright-field microscopy (40X) after color development using an immunoperoxidase kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and counter-staining with Gill’s hematoxylin to observe cell nuclei.

Data analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) values. Comparisons in mean follicle and oocyte diameter as well as numbers of granulosa cells among follicle stages were performed by Kruskal-Wallis One Way Analysis of Variance on Ranks using Sigma Stat (SigmaStat, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison. The relationship between follicle diameter and oocyte size was determined using Pearson Product Moment correlation analysis. The association between follicle diameter and granulosa cell number was determined using polynomial regression analysis. The level of significance was set at 95%.

Results

Changes in follicle and oocyte diameters and granulosa cell numbers during follicle development

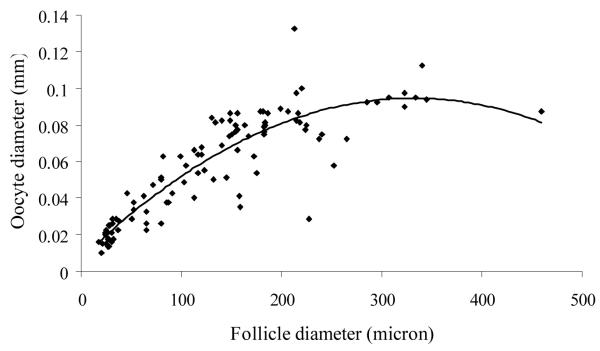

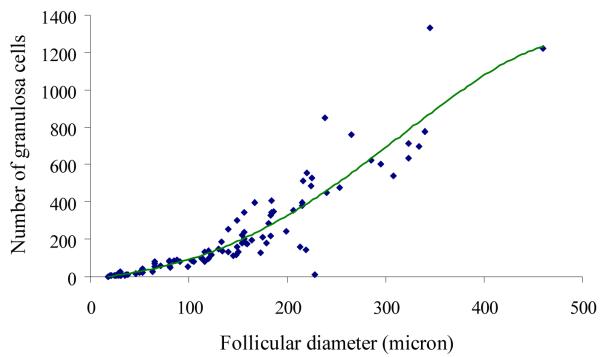

Although number of dogs per breed was low, there was no apparent difference in follicle/oocyte size among various races (data not shown). Primordial and primary follicles were similar (P > 0.05) in size and smaller than the progressively increasing (P < 0.05) diameters of secondary and early antral, respectively (Table I). However, there were no significant differences (P > 0.05) in the size of early and antral follicles (Table I). Diameter differed (P < 0.05) among oocytes derived from primordial, primary, secondary and early antral follicles with no difference (P > 0.05) thereafter (Table I). Follicle diameter correlated highly (P < 0.01; r2 = 0.83) with oocyte diameter (Fig. 2). Quadratic regression analysis revealed that granulosa proliferation increased with progressive folliculogenesis (P < 0.01; r2 = 0.87) (Fig. 3).

Table I.

Follicle and oocyte diameters at different developmental stages in the domestic dog. Different superscripts (a,b) within the same column indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05).

| Developmental stage |

Mean ± SEM diameter (micron) (range) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Follicle | Oocyte | |

| Primordial | 25 ± 0.8 (17.5 - 31)a | 18.5 ± 1.0 (10 - 26)a |

| Primary | 59.0 ± 13.8 (20 – 98)ab | 31.0 ± 3.1 (16 – 62.5)b |

| Secondary | 131.2 ± 6.0 (80 -218)b | 60.5 ± 2.7 (35 -88)c |

| Early antral | 229.8 ± 11.1 (153 -333)c | 83.6 ± 2.6 (57 -110)d |

| Antral | 492.0 ± 42.1 (322-665)c | 91.2 ± 3.8 (70-110)d |

Figure 2.

Correlation between follicle and oocyte diameter from primordial to small antral stage in the domestic dog. Oocyte diameter increased (P < 0.01) with follicular size.

Figure 3.

Regression analysis of follicle diameter compared to granulosa cell number from primordial to small antral stage in the domestic dog. Granulosa cell proliferation increased (P < 0.01) with follicular size.

Expression and localization of FGF-2 and -7

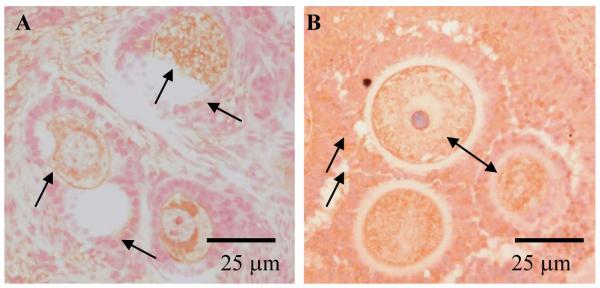

Immunohistochemistry analysis indicated that both FGF-2 and -7 were expressed in dog ovaries, with patterns varying with stage of (1) follicular development and (2) the reproductive cycle. Specifically, FGF-2 was detectable in oocytes and granulosa cells derived from primordial, primary and secondary follicles in all reproductive stages except during anestrus (Fig. 4). FGF-7 widely expresses in ovarian stroma (Fig. 5). Furthermore, it was localized in granulosa cells of primary follicle and in both granulosa and theca cells of secondary follicles in all reproductive stages and in only the theca layer of antral follicles in proestrous and estrous bitches (Fig. 5), but was not observed in ovarian sections of pre-pubertal counterparts.

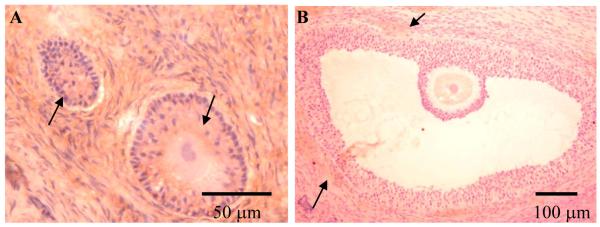

Figure 4.

FGF-2 protein expression in dog ovarian follicles (arrows). No specific staining was observed for the negative control (not shown). For ovarian sections exposed to primary antibody, FGF-2 expression occurred in oocytes and granulosa cells of primordial (not shown), primary (A) and secondary follicles (B) in all stage of reproductive cycle except during anestrus.

Figure 5.

FGF-7 protein expression in dog ovarian follicles (arrows). No specific staining was observed for the negative control (not shown). For ovarian sections exposed to primary antibody, FGF-7 expression occurred in granulosa cells of primary (not shown) and granulosa and theca cells of secondary follicles (A) in all reproductive cycle stages as well as in antral follicle theca cells (B) during proestrus and estrus.

Discussion

This study was the first to fill the knowledge gap in characterizing the temporal development profile of ovarian follicles, oocytes and granulosa cell numbers in the domestic dog. Classification of ovarian follicles and representative sizes at each developmental stage have been reported earlier for this species (Andersen and Simpson, 1973; Durrant et al., 1998; Barber et al., 2001). However, it was somewhat surprising that no effort had been directed at interrelating changes in follicle and oocyte diameter as well granulosa cell number over time and in the context of stages of the reproductive cycle. Such basic information is critical as science is advanced to effectively recover, mature and fertilize intraovarian oocytes, either by conventional in vitro maturation (IVM) of oocytes (Otoi et al., 2001; Songsasen and Wildt, 2005) or novel approaches such as culturing follicles (Xu et al., 2006). Knowing normative values and relationships in ovarian tissues unperturbed by hormones or other estrous synchronizing protocols is essential scholarly knowledge that has considerable, eventual practical application. From the primordial to antral stage, there was an overall four-fold increase in oocyte diameter and ~18-fold enhancement in follicle size. More specifically, there was a two phase development pattern, the first being ‘preantral’ (primordial to secondary) where follicle size increased along with the greatest enlargement of the oocyte combined with initiation and then significant granulosa cell proliferation. During the second, or ‘antral’ phase (early antral to antral), follicle size nearly redoubled mostly because of a further marked increase in granulosa cell number and vast accumulation of antral cavity fluid. At this time, the data suggested that the oocyte had achieved maximal growth with a barely perceptible increase in size.

Overall, we determined that progressive oocyte size was tightly linked with growing follicular diameter, an observation that has been made earlier in the pig (Mobeck et al., 1992). It also is known that the freshly ovulated dog oocyte measured without the ZP is 84.4 ± 0.6 μm (range 58.5 to 107.7; Reynald et al., 2005) in size, which is similar to the gamete derived from early and antral follicles observed in this study. Based on the finding observed in the present study and that of previous investigation, it is likely that dog oocytes achieve the maximum size when the antral cavity is formed. However, finding from our earlier work indicates that few oocytes recovered from small antral (< 1 mm) follicles had the capacity to complete in vitro nuclear maturation compared to a high proportion collected from large (> 2 mm) counterparts (Songsasen and Wildt, 2005). This suggests that although the oocyte recovered from growing antral follicles have achieved their optimal size, they have not acquired functional competency. We suspect that the oocyte requires intracellular modification during subsequent stages (i.e. advanced antral and preovulatory) of follicle development before it can be fully capable of completing nuclear maturation, fertilization and forming an embryo.

Follicle/oocyte growth patterns have been investigated in other mammals. It is clear that profiles of follicle development vary temporally among taxa, and that final follicle size ultimately is related to body mass for each species. For example, initially the mean size of the dog primordial follicle (25.0 μm, range 17.5 to 31 μm, this study) was similar to that of the hamster and pig (26 and 29.1 μm, respectively), but slightly smaller than that of the human (44 μm) (Griffin et al., 2006). However, as the follicle grows to near maturity, species body mass appears more related to final follicle size. For example, mean diameter of the early antral dog follicle (229.8, range, 153 to 333 μm) was much smaller than that of the pig (600 μm) or human (~900 μm) (Griffin et al., 2006). Unlike variations in antral follicle size, there is less overall comparative differences in final mature oocyte diameter (dog, 113 μm, Reynald et al., 2005; pig, 105 μm, Griffin et al., 2006; human and cow, 120 μm, van den Hurk and Zhao, 2005). However, interestingly there are species variations in the pattern of how these cells grow. For example, pig and human oocytes reach maximal size at the onset of antral cavity formation (Mobeck et al., 1992; Griffin et al., 2006), whereas rodent oocytes achieve the maximal size at the multi-layered preantral stage (van den Hurk and Zhao, 2005). Similar to the pig and human, dog oocyte reached their maximal size at the early antral stage.

The present study also demonstrated that granulosa cell proliferation was tightly linked to follicle diameter in a polynomial fashion, an observation also made earlier in other mammals, including the pig and human (Mobeck et al., 1992; Griffin et al., 2006). Granulosa cells were first perceptible associated with dog oocytes in primordial follicles, with the most marked increase in density occurring after antral cavity formation (> six-fold increase from the secondary to late antral stage). We suspect this later surge was likely due to the influence of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) that is known to be vital for terminating anestrus and initiating folliculogenesis in the dog (Kooistra and Okkens, 2001). Small growing follicles are FSH-responsive (McGee and Hsueh, 2000; Richards, 2001) with this hormone influencing granulosa cell proliferation by altering gene expression (Richards, 2001). Although not yet determined in the dog, FSH also promotes follicle growth and survival in other species by interacting with insulin like growth factor that, in turn, stimulates FSH receptor synthesis to enhance granulosa cell sensitivity to gonadotropin (Richards, 2001; Quirk et al., 2004; van den Hurk and Zhao, 2005). Further study aiming at examining expression of FSH-receptor in the granulosa cell of various follicle stages is needed to confirm the role of FSH on granulosa cell proliferation in the dog.

Our study also demonstrated the temporal expression pattern of two growth factors known to play important roles in folliculogenesis in other mammal species (van den Hurk and Zhao, 2005). Both FGF-2 and FGF-7 were discovered in dog ovarian follicles, but in a pattern that indicative of differentiated roles. FGF-2 expressed in oocytes and granulosa cells of primordial and primary follicles, suggesting that this growth factor is involved in activating the dog follicle. Our finding is consistent to with reports in other mammalian species supporting the contention that this growth factor probably has a highly conserved purpose among mammals. Specifically, FGF-2 expresses in granulosa cells and oocytes in primordial follicles of the rat (Nilsson et al., 2001) and cow (van Wezel et al., 1995), indicating its wide-spread role in initiating folliculogenesis (van den Hurk and Zhao, 2005). More recently, FGF-2 has been shown to activate in vitro primordial follicle growth in the goat (Matos et al., 2007a,b) and is strongly expressed in the granulosa and theca cells of multi-layered preantral and antral human follicles (Yamamoto et al., 1997). Finally, FGF-2 appears to assist in developing the vasculature of the human (Yamamoto et al., 1997) and cow (Robinson et al., 2007) corpus luteum. To date, we have obtained too few ovaries from diestrus bitches to adequately study the function of FGF-2 on angiogenesis of the dog corpus luteum, which continues to be a priority. Overall, it appears that FGF-2 probably exerts its primary effect early in dog folliculogenesis and has a minimal impact in antral cavity formation.

In contrast, FGF-7 expressed in both preantral and antral stage dog follicles. Specifically, this growth factor was found in the granulosa cells of primary follicle and both granulosa and theca cells of secondary follicles in all reproductive stages and also was only localized in theca cells of antral follicles during proestrus and estrus. FGF-7 has been found to be produced by theca cells of multi-layered preantral follicles, whereas its receptor localize in the granulosa cell in cows (Parrott and Skiner, 1998). This growth factor suppresses apoptosis and promotes in vitro growth of secondary rat follicles (McGee et al., 1999) and stimulates primordial follicle activation by upregulating kit ligand expression (Kezele et al., 2005). Expression of FGS-7 is hormone sensitive with estrogen and human chorionic gonadotropin stimulating production of this growth hormone in theca cells (Parrot and Skinner, 1998), whereas progesterone also is known to be a potent regulator (Koji et al., 1994). These observations are consistent with what is known about detailed periovulatory endocrine relationships (Wildt et al., 1977, 1979, review Concannon et al., 1989) as well as from present observations. For example, although estrogen is a dominant characteristic of proestrus, estrus is characterized by elevated (but declining) circulating estrogen and rising progesterone along with visible changes in follicular luteinization (Wildt et al., 1977, 1979). Therefore, it is reasonable to suspect that the elevated steroid concentrations observed in the bitch during proestrus and estrus probably are related to the enhanced FGF-7 expression measured in the present study in dog theca cells. Regardless, it was apparent that this particular growth hormone appeared to play its most significant role in the later stages of dog folliculogenesis.

In summary, there are some consistencies in ovarian follicle/oocyte development compared to other mammals, including the rather remarkable increase in sheer follicle size that occurs in parallel by a simultaneous, significant (albeit less robust) increase in oocyte diameter. We also demonstrate that dog oocytes derived from early antral stages have reached maximal physical size; thus their incapability to complete in vitro nuclear maturation (as demonstrated in earlier study) is not due to an inadequate physical size, but rather to the lack of essential intracellular components. In the present study, we demonstrate temporal expression pattern of FGF-2 and -7 in dog ovarian follicles; however other approaches, such as in vitro follicle culture may be essential to define regulatory roles of these growth factors in folliculogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the contributing veterinary hospitals in Front Royal, Stephens City, Harrisonburg and Winchester, VA areas for providing dog ovaries for the study. This study was supported by NIH-KO1RR020564.

References

- Andersen AC, Simpson ME. The Ovary and Reproductive Cycle of the Dog (Beagle) Geron-X Inc.; Los Altos: 1973. p. 290. [Google Scholar]

- Barber MR, Lee SM, Steffens WL, Ard M, Fayrer-Hosken RA. Immunolocalization of zona pellucida antigens in the ovarian follicle of dogs, cats, horses and elephants. Theriogenology. 2001;55:1705–1717. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(01)00514-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berisha B, Sinowatz F, Schams D. Expression and localization of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family members during the final growth of bovine ovarian follicles. Mol Reprod Dev. 2004;67:162–171. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore DG, Baillie LR, Holt JE, Dierkx L, Aitken RJ, McLaughlin EA. Biosynthesis of the canine zona pellucida requires the integrated participation of both oocytes and granulosa cells. Biol of Reprod. 2004;71:661–668. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.028779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buratini J, Pinto MGL, Castilho AC, Amorim RL, Giometti IC, Portel VM, Nicola ES, Price CA. Expression and function of fibroblast growth factor 10 and its receptor, fibroblast growth factor 2B, in bovine follicles. 2007. pp. 743–750. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Concannon PW, McCann JP, Temple M. Biology and endocrinology of ovulation, pregnancy, and parturition in the dog. J Reprod Fertil (Suppl) 1989;39:3–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demeestere I, Centner J, Gervy C, Englert Y, Delbaere A. Impact of various endrocrine and paracrine factors on in vitro culture of preantral follicles in rodents. Reproduction. 2005;130:147–156. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driancourt MA, Reynaud K, Cortvridt R, Smith AJ. Roles of kit and kit ligand in ovarian function. Rev Reprod. 2000;5:143–152. doi: 10.1530/ror.0.0050143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant BS, Pratt NC, Russ KD, Bolamba D. Isolation and characterization of canine advanced preantral and early antral follicles. Theriogenology. 1998;49:917–932. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(98)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England GCW, Allen WE. Real-time ultrasonic imaging of the ovary and uterus of the dog. J Reprod Fertil (Suppl) 1989;39:91–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppig JJ. Oocyte control of ovarian follicular development and function in mammals. Reproduction. 2001;122:829–838. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kezele P, Nilsson EE, Skinner MK. Keratinocyte growth factor acts as a mesenchymal factor that promotes ovarian primordial to primary follicle transition. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:967–973. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.043117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight PG, Glister C. Focus on TGF-b signaling. Reproduction. 2006;132:191–206. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.01074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koji T, Chedid M, Rubin JS, Slayden OD, Csaky KG, Aaronson SA, Brenner RM. Progesterone-dependent expression of keratinocyte growth factor mRNA in stromal cells of the primate endometrium: keratinocyte growth factor as a progestomedin. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:393–401. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin J, Emery BR, Huang I, Peterson CM, Carrell DT. Comparative analysis of follicle morphology and oocyte diameter in four mammalian species (mouse, hamster, pig and human) J Exp Clin Assisted Reprod. 2006;3:2. doi: 10.1186/1743-1050-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooistra HS, Okkens AC. Role of changes in the pulsatile secretion pattern of FSH in initiation of ovarian folliculogenesis in bitches. J Reprod Fertility (Suppl) 2001;57:11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos MH, van den Hurk R, Lima-Verde IB, Luque MC, Santos KD, Martins FS, Báo SN, Lucci CM, Figueiredo JR. Effects of fibroblast growth factor-2 on the in vitro culture of caprine preantral follicles. Cells Tissues Organs. 2007a;186:112–120. doi: 10.1159/000103016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos MH, Lima-Verde IB, Bruno JB, Lopes CA, Martin FS, Santos KD, Rocha RM, Silva JR, Bao SN, Fiqueiredo JR. Follicle stimulating hormone and fibroblast growth factor-2 interact and promote goat primordial follicle development in vitro. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2007b;19:677–684. doi: 10.1071/rd07021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee EA, Hsueh JW. Initial and cyclic recruitment of ovarian follicles. Endocrine Rev. 2000;21:200–214. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.2.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee EA, Chun SY, Lai S, He Y, Hsueh AJ. Keratinocyte growth factor promotes the survival, growth and differentiation of preantral follicles. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:732–738. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00547-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobeck DE, Esbenshade K, Flowers WL, Britt JH. Kinetics of follicle growth in the prepubertal gilt. Biol Reprod. 1992;47:485–491. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod47.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson E, Parrott JA, Skinner MK. Basic fibroblast growth factor induces primordial follicle development and initiates folliculogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;175:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00391-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien SJ, Murphy WJ. A dog’s breakfast? Science. 2003;301:1854–1855. doi: 10.1126/science.1090531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otoi T, Fujii M, Tanaka M, Ooka A, Suzuki T. Canine oocyte diameter in relation to meiotic competence and sperm penetration. Theriogenology. 2000;54:535–542. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(00)00368-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otoi T, Ooka A, Murakami M, Karja N. W. Kurniani, Suzuki T. Size distribution and meiotic competence of oocytes obtained from bitch ovaries at various stages of the oestrous cycle. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2001;13:151–155. doi: 10.1071/rd00098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott JA, Skinner MK. Developmental and hormonal regulation of keratinocyte growth factor expression and action in the ovarian follicle. Endocrinology. 1998;139:228–235. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.1.5680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patronek GI. Development of a model for estimating the size and dynamics of the pet dog population. Anthrozoos. 1994;7:25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DF. Companion animal medicine in the age of medical genetics. J Vet Intern Med. 2000;14:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennisi E. A shaggy dog history. Science. 2002;298:1540–1542. doi: 10.1126/science.298.5598.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picton HM. Activation of follicle development: the primordial follicle. Theriogenology. 2001;55:1193–1210. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(01)00478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk SM, Cowan RG, Harman RM, Hu C-L, Porter DA. Ovarian follicular growth and atresia: the relationship between cell proliferation and survival. J Anim Sci (Suppl) 2004;82:E40–E52. doi: 10.2527/2004.8213_supplE40x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynaud K, Fontbonne A, Marseloo N, Thoumire S, Chebrout M, de Lesegno CV, Chastant-Maillard S. In vivo meiotic resumption, fertilization and early embryonic development in the bitch. Reproduction. 2005;130:193–201. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JS. The ovarian follicle-a perspective in 2001. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2184–2193. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.6.8223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson RS, Nicklin LT, Hammond AJ, Schams D, Hunter MG, Mann GE. Fibroblast growth factor 2 is more dynamic than vascular endothelial growth factor A during the follicle-luteal transition in the cow. Biol Reprod. 2007;77:28–36. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.055434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songsasen N, Wildt DE. Size of the donor follicle, but not stage of reproductive cycle or seasonality, influences meiotic competency of selected domestic dog oocyte. Mol Reprod Dev. 2005;72:113–119. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songsasen N, Wildt DE. Oocyte biology and challenges in developing in vitro maturation systems in the domestic dog. Anim Reprod Sci. 2007;91:2–22. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanel-Borowski K, Calvo W. Short- and long-term response of the adult dog ovary after 1200 R whole body X-irradiation and transfusion of mononuclear leukocytes. Inter J Radiation and Biol. 1982;41:657–670. doi: 10.1080/09553008214550751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesoriero JV. Early ultrastructural changes of developing oocytes in the dog. J Morph. 1981;168:171–179. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051680206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai KL, Clark LA, Murphy KE. Understanding hereditary diseases using the dog and human as companion model systems. Mamm Genome. 2007;18:444–451. doi: 10.1007/s00335-007-9037-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Hurk R, Zhao J. Formation of mammalian oocytes and their growth, differentiation and maturation within ovarian follicles. Theriogenology. 2005;63:1717–1751. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wezel IL, Umapathysivam K, Tilley WD, Rodgers RJ. Immunohistochemical localization of basic fibroblast growth factor in bovine ovarian follicles. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1995;115:133–140. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(95)03678-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildt DE, Levinson CJ, Seager SWJ. Laparoscopic exposure and sequential observation of the ovary of the cycling bitch. 1977. pp. 443–449. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wildt DE, Panko WB, Chakraborty P, Seager SWJ. Relationship of serum estrone, estradiol-17b and progesterone to LH, sexual behavior and time of ovulation in the bitch. Biol Reprod. 1979;20:648–658. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod20.3.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Kreeger PK, Shea LD, Woodruff TK. Tissue engineered follicles produce live fertile offspring. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2739–2746. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Konishi I, Nanbu K, Komatsu T, Mandai M, Kuroda H, Matsushita K, Mori T. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1997;11:223–230. doi: 10.3109/09513599709152538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]