Abstract

The effect of cellular crowding was examined from molecular dynamics simulations of chymotrypsin inhibitor 2 (CI2) in the presence of either lysozyme or bovine serum albumin (BSA) crowder molecules as a complement to recent experimental studies of the same systems (Miklos, A. C.; Sarkar, M.; Wang, Y.; Pielak, G. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 7116). The simulations confirm a destabilization and significantly slowed diffusion of CI2 in the presence of lysozyme and indicate that this observation is a result of extensive, non-specific protein-protein interactions between CI2 and lysozyme. CI2 interacts much less with BSA crowders corresponding to a weak effect of crowding. Energetic analysis suggests an overall favorable crowding free energy in the presence of lysozyme while weaker interactions with BSA appear to be unfavorable.

Keywords: protein-protein interactions, diffusion, free energy of crowding, molecular dynamics

INTRODUCTION

Crowding in biological cells exerts a modulating effect on biomolecular structure and dynamics1,2. Furthermore, cellular environments modulate kinetic properties such as diffusion3 and association rates4,5 that are of importance for understanding cellular dynamics6,7. Past studies of crowding have focused largely on volume exclusion by crowder molecules. Theoretically, this effect is often modeled with hard sphere crowders2, while polymer-based crowding agents are used in corresponding experimental work2. The main finding from these studies is that volume exclusion due to crowding favors compact states over extended states8,9 thereby destabilizing the denatured state and stabilizing the folded state as well as aggregates and complexes.

Recently, this entropy-centered view of crowding has been challenged by NMR, fluorescence, and mass spectrometry measurements of protein stability in concentrated protein solutions10–12 and biological cells13. The emerging view is that crowded biological environments tend to destabilize rather than stabilize native protein structures. This suggests that enthalpic contributions may be at least as important as the volume exclusion effect. Electrostatic interactions and effectively reduced dielectric response of the environment presumably play a dominant role14–16, but details remain unclear.

Particularly interesting is the recent study of chymotrypsin 2 (CI2) in concentrated solutions of bovine serum albumin (BSA) and lysozyme10. It was found that BSA marginally destabilized CI2 while lysozyme had a more pronounced destabilizing effect. It is not clear, though, why exactly CI2 is destabilized in the presence of the protein crowders and why there is a large difference between lysozyme and BSA crowders. Here, we follow up on this work with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the same systems with the specific goal to understand the molecular origins of how CI2 is destabilized differentially in the presence of the protein crowders. In particular, we relate the different nature of protein-protein interactions between CI2 and lysozyme vs. CI2 and BSA to different effects of crowding by proteins.

In the following, we will first describe the computational methodology followed by a presentation and discussion of the simulation results.

METHODS

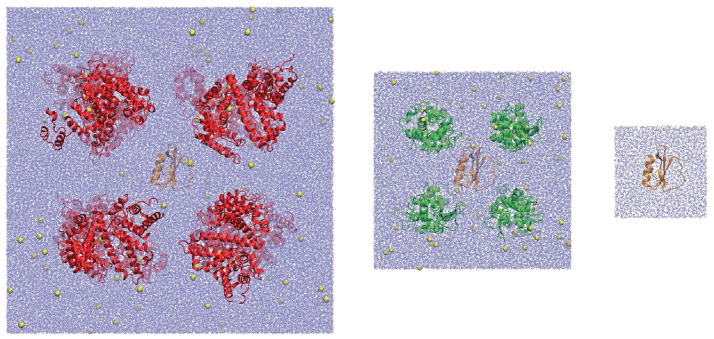

Three MD simulations (at 298K, 1 atm pressure) were set up to mimic the experimental conditions. In the first (referred to as CI2W), a single molecule of CI2 was simulated in explicit solvent, representative of infinite dilution. In the second and third simulations, CI2 was simulated in the presence of eight lysozyme (CI2LYS) and eight BSA (CI2BSA) molecules, respectively, also with explicit solvent and counterions for charge neutralization (cf. Fig. 1). The box size was set to match the experimental conditions of 100 g protein/L solution (cf. Table 1). The crowder volume and weight fractions are 7% and 10%, respectively, which are at the low end of typical cellular conditions.

Figure 1.

Simulated systems from left to right: CI2BSA, CI2LYS, and CI2W. CI2: orange; BSA: red; lysozyme: green; ions: yellow.

Table 1.

Simulated systems

| System Solute(s) | Waters | Ions | Average box length (cubic size) [Å] | Crowder concentration [g/L] | Crowder volume fraction [%] | Simulation length [ns] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI2W | CI2 | 5839 | - | 56.66 | - | - | 160 |

| CI2LYS | CI2 + 8 × lysozyme | 55656 | 64 Cl− | 121.55 | 105.9 | 6.97 | 244 |

| CI2BSA | CI2 + 8 × BSA | 253302 | 136 Na+ | 201.27 | 108.2 | 7.22 | 117 |

Structures of CI2 and lysozyme were taken from the PDB structures 1YPC and 6LYZ, respectively. The structure for BSA was built via homology modeling based on the structure for human serum albumin (1AO6) using MODELLER17. Initial systems were setup by first placing CI2 at the origin. In the CI2LYS and CI2BSA, crowder molecules were placed at the eight corners of a cube far enough from CI2 to avoid close contacts between either the crowder molecules or between the crowders and CI2. Each of the systems was then solvated with explicit solvent in a cubic box large enough to achieve a crowder concentration of about 100g/L (cf. Table 1). Water molecules were subsequently replaced randomly by counterions to achieve charge neutrality (cf. Table 1). The initial systems were then minimized with 1000 steps of conjugate gradient minimization and subsequently heated in multiple steps to 298K (4ps @ 50K, 4ps @ 100K, 4ps @ 200K, 4ps @ 250K, and 10 ps @ 298K). Of the following production runs, the first 30 ns were considered equilibration time.

All of the simulations were run in the NTP ensemble with a Langevin thermo- and barostat using a damping coefficient of 5 ps−1. Periodic boundaries were used. Electrostatic interactions were calculated from particle-mesh Ewald18 summation using a direct space cutoff of 12 Å (with a switching function becoming effective at 10 Å). The same cutoff was applied to Lennard-Jones interactions. A time step of 2 fs was used in combination with SETTLE19 to constrain heavy atom-hydrogen bond distances. The CHARMM27 force field20 was used to describe protein-protein interactions in combination with a CMAP-based correction map for φ/ψ-torsions21,22. The CMAP used here was improved from the originally published map to reduce the sampling of α-helical conformations while enhancing sampling of PPII conformations and improving the agreement with NMR J-coupling values for alanine-based peptides23. The modified CMAP is available from the authors upon request. The TIP3P model24 was used to describe water interactions. The CI2W simulation was carried out for 160 ns, CI2BSA for 117 ns, and CI2LYS for 244 ns. Averages were calculated for 30–115 ns to exclude an initial equilibration time and cover the same amount of sampling from all trajectories.

The free energy of crowding is given as:

| (1) |

Changes in enthalpy and solvation free energies were estimated via an MMGB/SA approach25 based on snapshots taken at 100 ps intervals from the CI2LYS and CI2BSA simulations:

| (2) |

| (3) |

The enthalpy term was calculated from vacuum molecular mechanics force field energies. The solvation energies were calculated with the GBMV model26 and γ=0.005 cal/mol/Å2. A dielectric constant of ε=65 was used to account for a reduced dielectric response of water due to moderate crowding14,15. ΔΔGsolvation between ε=80 and ε=65 is about 4 kcal/mol for CI2. SASA is the solvent-accessible surface area.

To estimate the change in entropy for CI2, sampling in CI2W was compared with CI2LYS and CI2BSA. To estimate the change in entropy upon crowding for CI2, vibrational, translational, and rotational contributions were analyzed separately. Vibrational contributions were determined from quasi-harmonic analysis after removing translations and rotations of CI2. Only little difference was found between CI2 in water and in the presence of the crowders (cf. Table 5). Translational entropies were estimated by comparing sampling in CI2W and CI2LYS/CI2BSA. In order to focus on the remaining translational freedom in the presence of the crowder molecules a procedure similar to previous calculations of translational entropies in the context of protein-ligand binding27 was followed. More specifically, for each snapshot the following steps were carried out: 1) the closest crowder molecule from CI2 was identified based on heavy atom distances; 2) the crowder/CI2 pair was aligned to a reference crowder structure; 3) the center of mass and orientation of CI2 after superposition of the crowder structure was counted with a histogram to determine sampling of space and angular directions. This procedure provides the sampling of CI2 relative to the crowders. An accurate estimate of absolute entropies requires complete conformational sampling, which would require much longer simulations. Instead, a differential approach was used here, where results for the CI2LYS and CI2BSA simulations were compared with results from artificial trajectories, where the CI2 coordinates were replaced with the coordinates from the CI2W trajectory. The latter essentially represents a simulation of CI2 in the presence of the crowders but with no effective interaction or volume exclusion. Hence, a comparison between the two gives a direct estimate of the effect of crowding on translational entropies. Volumes were obtained from counting visited positions of the CI2 center of mass on a 3 Å grid. Rotational entropies were analyzed with the same approach after removing translational motion and using the area on the unit sphere traced out by the normalized vector between the Cα atom of residue 17 – at the center of the long helix of CI2 – and the center of mass of CI2. The visited volume was found to decrease by about half for both lysozyme and BSA. This is in part a result of excluded volume and in part due to association with the crowders. However, with both crowders the full rotational freedom was maintained (cf. Table 5). The change in entropy of the crowder molecules was neglected.

Table 5.

Estimated changes in entropy due to crowding

| Volume [Å3] | ΔΔStrans | Area on unit sphere | ΔΔSrot | ΔSvib QHA | ΔΔSvib | ΔΔStotal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI2W | 30–160 ns | 10.82 | ||||||

| CI2W/CI2LYSa | 30–160 ns | 14985 | 12.6 | |||||

| CI2W/CI2BSAa | 30–115 ns | 7128 | 11.6 | |||||

| CI2LYS | 30–160 ns | 7668 | −1.31 | 12.3 | ≈0 | 10.50 | −0.32 | −1.64 |

| CI2BSA | 30–115 ns | 4158 | −1.05 | 10.8 | ≈0 | 10.76 | −0.06 | −1.11 |

Estimated change in entropy of CI2 between dilute solvent and crowded environments. All entropies are given in units of [cal/mol/K].

conformations from CI2W relative to crowder positions in CI2LYS/CI2BSA

RESULTS and DISCUSSION

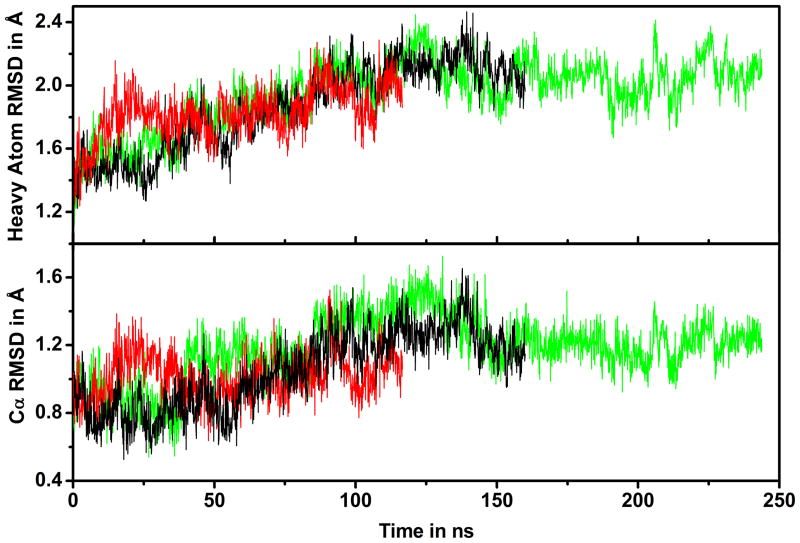

The CI2 structure remained stable during all of the simulations with average Cα-RMSDs of about 1 Å and heavy atom RMSDs of about 2 Å (cf. Table 2 and time series in Fig. 2). There was little difference between CI2 in dilute solvent and in the presence of BSA. The RMSD was slightly higher with lysozyme crowders (1.2 Å vs. 1.0 Å) and remained near that value during the entire CI2LYS simulation (cf. Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Root mean square deviations

| CI2 | Lysozyme | BSA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cα | Heavy | Cα | Heavy | Cα | Heavy | ||

| CI2W | 30–115 ns | 1.02 (0.19) | 1.85 (0.19) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 30-max | 1.11 (0.21) | 1.95 (0.21) | |||||

|

| |||||||

| CI2LYS | 30–115 ns | 1.18 (0.19) | 1.92 (0.17) | 1.06 (0.22) | 1.62 (0.20) | N/A | N/A |

| 30-max | 1.22 (0.16) | 2.01 (0.16) | 1.10 (0.32) | 1.68 (0.27) | |||

|

| |||||||

| CI2BSA | 30–115 ns | 1.01 (0.13) | 1.86 (0.14) | N/A | N/A | 3.45 (0.45) | 3.82 (0.41) |

| 30-max | 1.01 (0.13) | 1.86 (0.14) | 3.45 (0.44) | 3.83 (0.41) | |||

Average root mean square deviations (RMSD) in Å for CI2, lysozyme, and BSA with respect to initial structures. CI2 data is averaged over time. Lysozyme and BSA data is averaged over both time and multiple copies present in the CI2LYS and CI2BSA simulations, respectively. Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Figure 2.

Time series of Cα and heavy atom root mean square deviations (RMSD) for CI2 from initial structure after superposition for CI2W (black), CI2LYS (green), and CI2BSA (red) simulations.

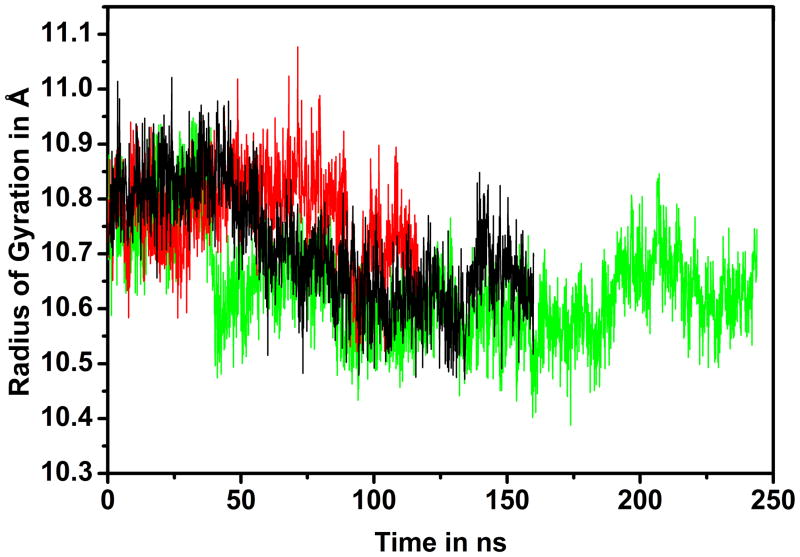

CI2 features an extended flexible loop for residues 35–45 that could potentially assume more compact conformations if constrained by the environment. To measure compaction of CI2, the radius of gyration was calculated. Without crowders, the average radius of gyration was 10.71 Å. We found a decrease in the presence of lysozyme to 10.64 Å but an increase with BSA crowders to 10.78 Å (cf. Fig. 3). The changes are small and essentially within the uncertainty given a standard deviation of 0.1 Å. Therefore, we cannot conclude clearly that crowding leads to compaction for this system.

Figure 3.

Time series of radius of gyration for CI2 for CI2W (black), CI2LYS (green), and CI2BSA (red) simulations.

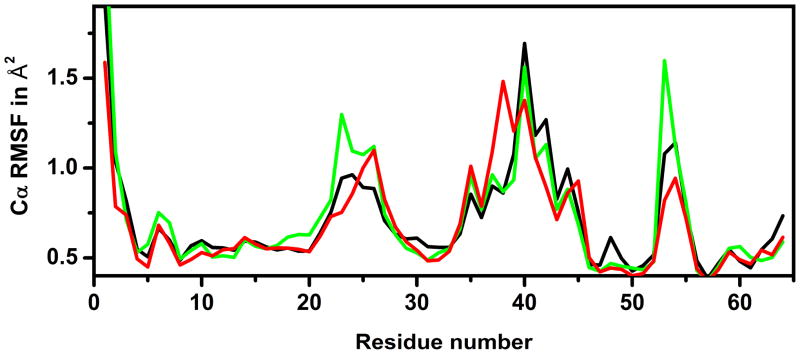

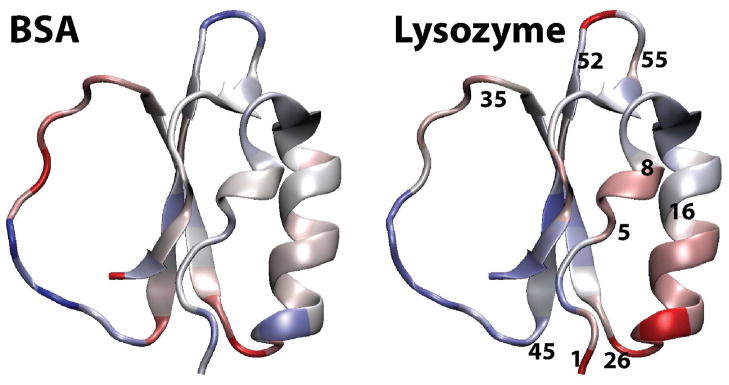

We subsequently examined root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) around the average structures from each of the simulations. Lysozyme crowding led to increased fluctuations in parts of the structure, in particular at residues 5–8, 16–26, and 52–55 (cf. Fig. 4). These residues map onto parts of the two N-terminal helices of CI2 (cf. Fig. 5) as well as the nearby loop connecting the strands of the central β-sheet. Interestingly, many of the same residues showed decreased thermodynamic stability in NMR experiments of the same system (cf. Fig. 1 in that work10). Hence, it appears that increased structural fluctuations around the native structure may partially explain the observed decrease in thermodynamic stability of the folded vs. the unfolded state. Additional residues of CI2 with decreased stability involve the central strand of the β-sheet. Since we did not see any significant increase in RMSF for this well-packed part of the CI2 structure, we hypothesize that reduced stability in this region is a result of partial unfolding on time scales not accessible by our sub-μs simulations.

Figure 4.

Cα root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) for CI2 during 30–115ns in CI2W (black), CI2LYS (green), and CI2BSA (red).

Figure 5.

Increased (red) and decreased (blue) Cα-RMSF of CI2 in the presence of BSA (left) and lysozyme (right).

In the case of BSA crowders, structural fluctuations were more similar to the non-crowded case and involved both increased and decreased fluctuations at different parts of CI2, which is generally in agreement with the experimental data10. The largest changes in the presence of BSA were seen in the extended loop, for which experimental data is not available10.

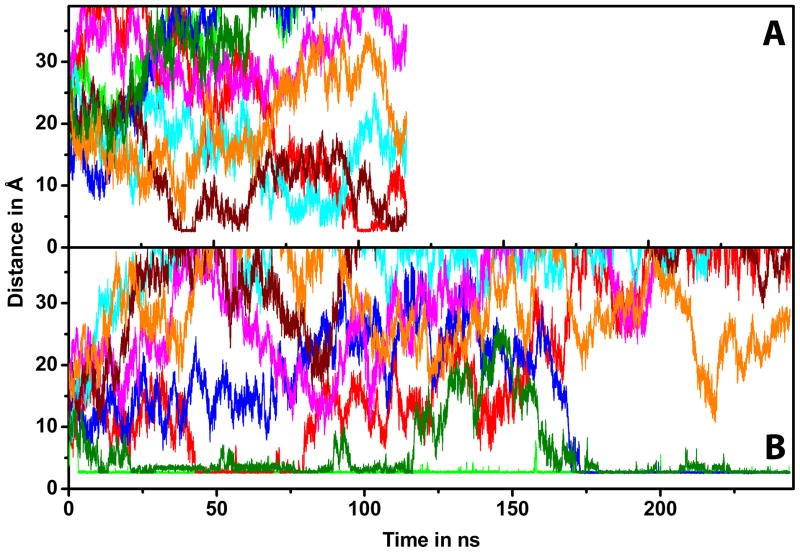

We now turn to an analysis of CI2-crowder interactions. On average, CI2 interacted with 2.6 lysozyme molecules but only 1.1 BSA molecules (cf. Table 3). CI2-crowder interactions involved different molecules coming on and off during the course of the simulations (cf. Fig. 6) but contacts were maintained much longer with lysozyme (>20 ns) than with BSA (<20 ns). A smaller number of interacting BSA molecules may simply be a consequence of the larger size of BSA, but the shorter contact times with BSA indicate that CI2-BSA interactions are inherently weaker. Moreover, BSA-BSA interactions were more extensive than lysozyme-lysozyme interactions with 1.9 average BSA-BSA contacts vs. 1.4 lysozyme-lysozyme contacts (cf. Table 3). Taken together, this data suggests that BSA favors other BSA molecules over CI2 while lysozyme seems to favor CI2 over interactions with other lysozyme molecules.

Table 3.

Average number of contacted crowder molecules

| CI2LYS | CI2BSA | |

|---|---|---|

| CI2 | 2.59 (0.51) | 1.11 (0.59) |

| Lys.-Lys. | 1.36 (0.50) | N/A |

| BSA-BSA | N/A | 1.85 (0.78) |

Averaged over 30–115 ns with standard deviations in parentheses. Contacts have a minimum heavy atom distance of less than 10 Å.

Figure 6.

Minimum distance between CI2 and BSA (A) or lysozyme (B) crowders based on heavy atom distances as a function of simulation time. Different colors indicate different crowder atoms.

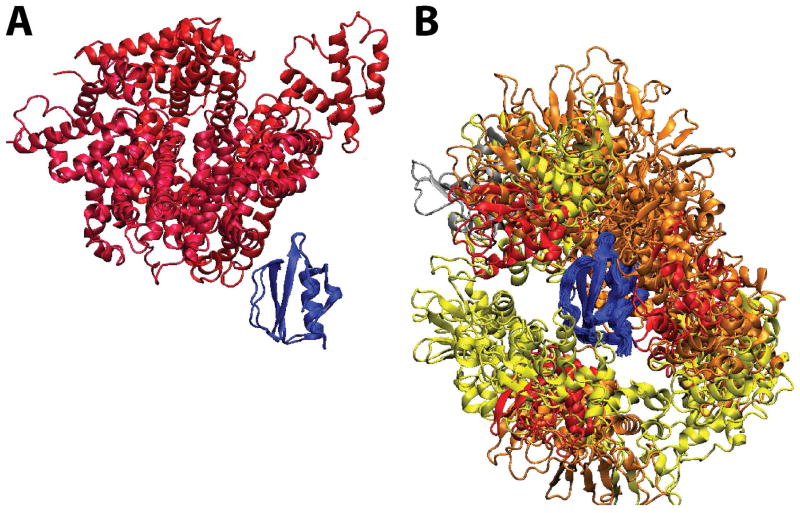

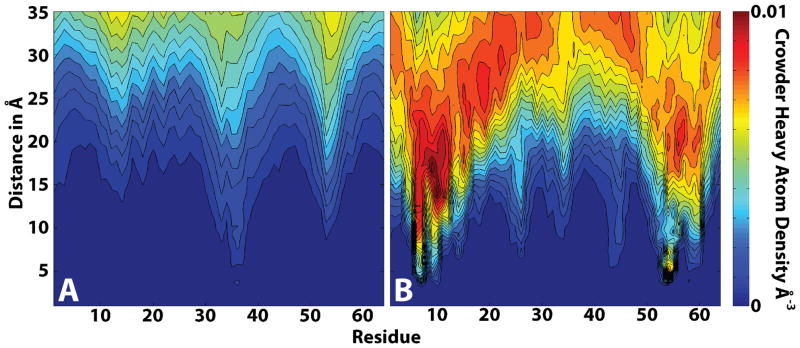

Representative CI2-crowder interactions are shown in Fig. 7. There are extensive close-range interactions with lysozyme in contrast to only few interactions with BSA. This is further illustrated with time-averaged radial distributions of crowder heavy atoms around each residue of CI2 (cf. Fig. 8). Again, there are extensive interactions between CI2 and lysozyme that were strongest near the N- and C-termini of CI2, but involved the entire structure of CI2. The picture is entirely different for CI2-BSA interactions with few close contacts, mostly near the extended loop. Comparing Fig. 8 with Fig. 4, one finds that most residues with the closest crowder contacts also exhibited increased RMSF. This suggests that direct protein-protein contacts are responsible for the destabilization of the CI2 structure in the presence of lysozyme.

Figure 7.

Representative structures of CI2 contacts with BSA (A) and lysozyme (B) crowder molecules obtained via K-means clustering (15 Å radius) of complexes with minimum contact distance of less than 10 Å during 30–115ns. Structures closest to the cluster centers for clusters with contact distances below 6 Å are shown. Coloring indicates cluster size relative to total number of structures (red: >5%; orange: <5%, >1.5%; yellow: <1.5%).

Figure 8.

BSA (A) and lysozyme (B) crowder heavy atom radial densities around Cα atoms of CI2 residues during 30–115 ns. Color coding indicates number densities according to color bar.

The free energy of crowding (i.e. transfer from aqueous solvent to a crowded environment) was calculated as described in the Methods section. There are significant changes in enthalpy and solvation free energies due to crowding, especially in the case of lysozyme due to more extensive interactions (cf. Table 4), but enthalpy and solvation changes largely cancel each other. The CI2 entropy is reduced modestly, mostly resulting from a partial loss of translational entropy (cf. Table 5). The overall crowding free energy is estimated to be negative with lysozyme and positive with BSA with a difference of 9.1 kcal/mol. An intriguing conclusion from this data is that in a heterogeneous cellular environment a solute would be drawn to an environment where more extensive protein-protein contacts are possible even if there is no strong specific binding. This may suggest a thermodynamic driving force towards spatial organization of proteins in cellular environments.

Table 4.

Estimated free energies of crowding

| ΔΔH | ΔΔGsolv | −TΔΔS | ΔΔG80/65 | ΔΔGcrowding | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSA | −21.3 (1.6) | 22.9 (1.54) | 0.3 (0.1) | 4.2 (0.9) | 6.1 (0.3) |

| Lys | −194.0 (2.0) | 186.2 (1.95) | 0.5 (0.1) | 4.3 (0.6) | −3.0 (0.5) |

[kcal/mol] with statistical errors given in parentheses; T=298K. Averages over the trajectories exclude the first 30 ns.

Our calculation of the free energy of crowding based on simulations of a solute in the presence of crowder molecules accounts for conformational responses resulting from solute-crowder interactions but is limited to folded states of the solute and may suffer from poor statistics due to slow kinetics of sampling different solute-crowder interactions. Alternatively, estimates of free energies of crowding can also be obtained with a post-processing approach where only the crowder molecules are simulated first and free energies for insertion of solute molecules are then obtained with a Widom-type particle insertion method16,28. The advantage of this approach that very different solute conformations can be readily tested, in particular folded and unfolded states but at the expense of neglecting changes in solute or crowder conformations due to solute-crowder interactions because the systems are not simulated together. However, the general conclusions of such studies that non-specific protein-protein interactions are capable of destabilizing native solutes16 are in agreement with our findings.

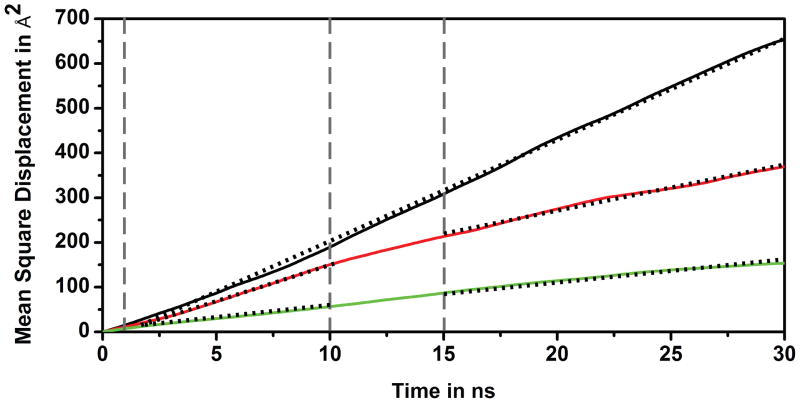

Finally, we will discuss translational diffusion constants as a function of crowding. A comparison of MSD as a function of time shows that diffusion was slowed down in the presence of the crowder molecules (cf. Fig. 9). Furthermore, diffusion constants with BSA appear to be significantly different for short times (<10 ns) vs. longer times (>15 ns). Hence, we determined diffusion constants from the slope of MSD vs. time according to the Einstein relationship for two regimes: 1–10 ns and 15–30 ns (cf. Table 6). The long-time diffusion constant is reduced by half in the presence of BSA and to about one fourth with lysozyme. These results are in reasonable agreement with experimental data29 but there is a general overestimation of diffusion rates, especially in dilute solvent. This is likely a result of the TIP3P water model used here, which is known to result in overestimated diffusion rates30.

Figure 9.

Mean square displacement (MSD) for CI2 center of mass in CI2W (black), CI2LYS (green), and CI2BSA (red) simulations using all data after 30 ns. Vertical lines indicate short (1–10 ns) and long (15–30 ns) time regimes. Dashed lines indicate linear fits used to estimate diffusion coefficients.

Table 6.

Diffusion constants of CI2

| 1–10 ns | 15–30 ns | Experiment29 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 31.8 | 31.7 | 15.5 |

| BSA | 26.6 | 14.2 | 8.2 |

| Lysozyme | 8.8 | 7.4 | 5.1 |

[μm2/s] obtained according to Einstein relationship from slope of mean square displacement vs. time

A significant difference in diffusion rates for different time regimes is an indication of anomalous diffusive behavior. Anomalous diffusion is expected for dynamics in crowded and confined media31, where motions over short distances are presumed to be less affected by the crowder obstacles than long-range diffusion. Diffusion of CI2 with BSA crowders fits this picture. The short-time diffusion rate is close to the rate in aqueous solvent but long-time diffusion is significantly slowed down. In contrast, diffusion in the presence of lysozyme does not seem to involve significant anomalous behavior. The diffusion rates were reduced significantly already for short time motions and changed little between the short- and long-time regimes. This fundamental difference in diffusive behavior in the presence of BSA and lysozyme can be explained by the difference in CI2 interactions between lysozyme and BSA. With BSA, there are few interactions so that CI2 can essentially move around freely until occasionally colliding with a BSA molecule. This is similar to the diffusive behavior seen in the presence of noninteracting hard sphere crowders. With lysozyme, CI2 is always involved in a complex with one or more crowder molecules. The larger complexes are expected to diffuse slower than CI2 alone. Furthermore, since there is little evidence of anomalous diffusion, it appears that these complexes act effectively like a larger molecule diffusing in dilute solvent.

CONCLUSIONS

The MD simulations provide a detailed view of how protein-protein interactions give rise to crowding effects in biological environments. The results directly complement recent experimental studies of the same systems10. The use of atomistic detail and full explicit solvent provides a more realistic description of crowding effects than in previous studies of crowding. In particular, protein-protein and protein-water interactions are described in a realistic fashion and hydrodynamic effects are fully included through the behavior of the explicit water molecules. However, the use of full atomistic detail limits accessible time scales to the sub-μs time regime.

The results presented here challenge the traditional view of biological crowding as being primarily a volume exclusion effect. Instead we propose that variable interactions between protein crowders and a given biomolecular solute are the key factor for understanding the effect of crowding in cellular environments. At one end of the spectrum, if a solute does not interact strongly with protein crowders, as in the CI2-BSA example, the solute structure and dynamics remains largely unaffected. The only significant effect was a moderate reduction in long-time diffusion rates due to the crowders acting as obstacles. On the other hand, strong interactions with protein crowders, as in the CI2-lysozyme example, lead to perturbations of the solute structure, experimentally measurable destabilization, and significant reduction in diffusion rates due to long-time association with crowders. The effect of crowding in real biological environments, where protein-protein interactions span a wide range, is therefore expected to dependent strongly on the local environment of a particular solute. Future studies will expand on the present work to a wider range of systems and different concentrations of crowder molecules.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ryuhei Harada for helpful discussions. Funding from NIH GM092949 (to M.F.), RIKEN-QBIC, and MEXT SPIRE Supercomputational Life Science (to YS) as well as computational resources at RIKEN-RICC are acknowledged.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CHARMM

Chemistry at Harvard molecular mechanics program

- CI2

chymotrypsin inhibitor 2

- CI2W

CI2 simulation in water

- CI2LYS

CI2 simulation with lysozyme

- CI2BSA

CI2 simulation with BSA

- CMAP

cross-correlation map for torsion angles

- MD

molecular dynamics

- MSD

mean-square displacement

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NTP

constant number, temperature, and pressure

- RMSD

root mean square deviation

- RMSF

root mean square fluctuation

- SASA

solvent-accessible surface area

- TIP3P

transferable intermolecular potential 3 point water model

Contributor Information

Michael Feig, Email: feig@msu.edu.

Yuji Sugita, Email: sugita@riken.jp.

References

- 1.Minton AP. Biopolymers. 1981;20:2093. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou HX, Rivas G, Minton AP. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dix JA, Verkman AS. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kozer N, Schreiber G. J Mol Biol. 2004;336:763. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wieczorek G, Zielenkiewicz P. Biophys J. 2008;95:5030. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.136291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ridgway D, Broderick G, Lopez-Campistrous A, Ruaini M, Winter P, Hamilton M, Boulanger P, Kovalenko A, Ellison M. Biophys J. 2008;94:3748. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.116053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi K, Arjunan SNV, Tomita M. Febs Letters. 2005;579:1783. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheung MS, Klimov D, Thirumalai D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409630102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou HX. J Mol Recognit. 2004;17:368. doi: 10.1002/jmr.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miklos AC, Sarkar M, Wang Y, Pielak GJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7116. doi: 10.1021/ja200067p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ignatova Z, Krishnan B, Bombardier JP, Marcelino AMC, Hong J, Gierasch LM. Biopolymers (Pept Sci) 2007;88:157. doi: 10.1002/bip.20665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghaemmaghami S, Oas TG. Nature Struct Biol. 2001;8:879. doi: 10.1038/nsb1001-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inomata K, Ohno A, Tochio H, Isogai S, Tenno T, Nakase I, Takeuchi T, Futaki S, Ito Y, Hiroaki H, et al. Nature. 2009;458:106. doi: 10.1038/nature07839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanizaki S, Clifford JW, Connelly BD, Feig M. Biophys J. 2008;94:747. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.116236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Despa F, Fernandez A, Berry RS. Phys Rev Lett. 2004:93. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.228104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGuffee SR, Elcock AH. PLoS Computational Biology. 2010;6:e1000694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanchez R, Sali A. Proteins. 1997;(Supplement 1):50. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(1997)1+<50::aid-prot8>3.3.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darden TA, York D, Pedersen LG. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:10089. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyamoto S, Kollman PA. J Comput Chem. 1992;13:952. [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacKerell AD, Jr, Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack JD, Evanseck MJ, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, et al. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:3586. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacKerell AD, Jr, Feig M, Brooks CL., III J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1400. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacKerell AD, Jr, Feig M, Brooks CL., III J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:698. doi: 10.1021/ja036959e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graf J, Nguyen PH, Stock G, Schwalbe H. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:1179. doi: 10.1021/ja0660406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:926. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gohlke H, Case DA. J Comput Chem. 2003;25:238. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee MS, Feig M, Salsbury FR, Jr, Brooks CL., III J Comput Chem. 2003;24:1348. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swanson JMJ, Henchman RH, McCammon JA. Biophys J. 2004;86:67. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74084-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qin SB, Minh DDL, McCammon JA, Zhou HX. J Phys Chem Lett. 2010;1:107. doi: 10.1021/jz900023w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Li C, Pielak GJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:9392. doi: 10.1021/ja102296k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Makarov VA, Feig M, Pettitt BM. Biophys J. 1998;75:150. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77502-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saxton MJ. Biophys J. 1994;66:394. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(94)80789-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]