Abstract

Malformations of the kidney and lower urinary tract are the most frequent cause of end stage renal disease in children. Mutations in HNF1B and PAX2 commonly cause of syndromic urinary tract malformation. We searched for mutations in HNF1B and PAX2 in North American children with renal aplasia and hypodysplasia (RHD) enrolled in the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children Cohort Study (CKiD). We identified 7 mutations in this multiethnic cohort (10% of patients). In HNF1B, we identified a nonsense (p.R181X), a missense (p.S148L), and a frameshift (Y352fsX352) mutation, and one whole gene deletion. In PAX2, we identified one splice site (IVS4–1G>T), one missense (p.G24E), and one frameshift (G24fsX28) mutation. All mutations occurred in Caucasians, accounting for 14% of disease in this subgroup. The absence of mutations in other ethnicities is likely due to limited sample size. There were no differences in clinical parameters (age, baseline eGFR, blood pressure, body mass index, progression) between patients with or without HNF1B and PAX2 mutations. A significant proportion of North American Caucasian patients with RHD carry mutations in HNF1B or PAX2 genes. These patients should be evaluated for complications (e.g. diabetes for HNF1B mutations, colobomas for PAX2) and referred for genetic counseling.

Keywords: HNF1B, PAX2, renal hypodysplasia, chronic kidney disease, children

Introduction

Renal hypodysplasia (RHD), encompassing the diagnosis of renal aplasia, hypoplasia, and dysplasia, is the second leading cause of chronic renal insufficiency (eCreatinine clearance ≤75ml/min per 1.73m2) in the pediatric population [1]. In the North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies (NAPRTCS) database, RHD was the primary diagnosis in 17.3% of the children with chronic kidney disease (CKD), 14% of children on dialysis, and 15.9% of children with renal transplants (https://web.emmes.com/study/ped/annlrept/Annual%20Report%20-2008.pdf).

The incidence of renal aplasia is 1 in 1300 [2]. Unilateral dysplastic kidneys occur in 1 in 1000, and bilateral dysplasia in 1 in 5000 of the general population [3]. Infants with severe bilateral kidney disease often die in the neonatal period secondary to Potter's sequence (i.e pulmonary hypoplasia secondary to inadequate renal function and amniotic fluid during pregnancy, ref.[4]). The likelihood of developing chronic renal failure in patients with bilateral dysplasia has been correlated with a calculated GFR of <15ml/min per 1.73m2 at 6 months of age; children with calculated GFR >15ml/min per 1.73m2 at that age tend to show improvement in renal function at follow-up [5].

Hereditary factors are partly responsible for RHD, as evidenced by familial aggregation of disease. For example, Roodhooft et al found a 9% incidence rate of asymptomatic renal malformations in parents and siblings of patients with RHD [6]. Moreover, RHD is a feature of at least 73 syndromic disorders, such as renal cysts and diabetes syndrome (RCAD), due to HNF1B mutations (OMIM 137920) or renal-coloboma syndrome (RCS), due to PAX2 mutations (OMIM 120330, ref. [7]). Although most cases of RHD are attributed to sporadic, nonsyndromic disease, studies have discovered mutations in HNF1B and PAX2 in up to 19.9% of European children diagnosed with RHD [8–11]. These data suggest that compared to clinical diagnosis, genetic screening can more accurately identify these syndromes and permit counseling of patients and family members regarding specific renal and extra-renal complications, such as diabetes in HNF1B and eye abnormalities in PAX2. The prevalence of PAX2 and HNF1B mutations has however not been determined in North American populations.

Methods

Subjects

CKiD is an NIH sponsored prospective observational cohort study of children with chronic kidney disease in the United States [12]. Details of the CKiD study design have been previously published. Briefly, eligible children are aged 1 to 16 years and have a Schwartz-estimated GFR between 30 and 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 [13]. Exclusion criteria include: renal, other solid-organ, bone marrow, or stem cell transplantation, dialysis treatment within the past 3 months, cancer/leukemia diagnosis or HIV diagnosis/treatment within past 12 months, current pregnancy or pregnancy within past 12 months, history of structural heart disease, genetic syndromes involving the central nervous system, and history of severe to profound mental retardation. Children were enrolled at 46 participating tertiary care pediatric nephrology programs across the U.S. and 2 sites in Canada. Institutional Review Boards for each participating site approved the study protocol. Of the 586 CKiD participants, at the time of the analysis 87 children were categorized as having RHD. We examined DNA samples from the 73 RHD patients that consented for genetic studies. Data collected at the baseline visit include demographic information including age and race, the medical record recorded diagnosis causing CKD, family history of kidney and cardiovascular disease, blood chemistries, age at diagnosis with CKD, GFR via plasma disappearance of iohexol (iGFR). The CKiD consent did not include permission to contact patients again to obtain additional clinical data. The study was approved by the CKiD Steering Committee and the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at Montefiore Medical Center and Columbia University.

Age, eGFR, body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressure were compared between mutation carriers and non-carriers by two-sided ttest with equal variance, adjusted in R version 2.12.0 (http://www.r-project.org/). P-values less than 0.05 were considered as significant.

Mutation Screening

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using standard protocols. Reference sequences of HNF1B and PAX2 were downloaded from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (37.1 Build) and an alternatively spliced exon 9 of PAX2 from the Ensembl genome browser. Primers were designed for the nine exons of HNF1B and 12 exons of PAX2 (including one alternate exon). Amplified PCR products were subjected to Sanger sequencing (n=73). Sequence analysis was performed using Sequencer 4.8 software. All putative variants were confirmed by bidirectional sequencing.

On mutational screening of HNF1B and PAX2, we found a total SNP rate per base pair (bp) of 1 SNP in every 284 bases surveyed (1 SNP/376 bp in coding regions, and 1 SNP/247 bp in introns), which is comparable to the average SNP distribution rate in the human genome.

Evaluation of rare variants

We evaluated all variants for potential pathogenicity using four methodologies. First, we consulted public databases (dbSNP, 1000 genomes) to determine if the variants were previously detected in reference populations. Coding variants that were not present in public databases were further cross-referenced with prior publications and mutation databases, such as Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD, ref. [14]. Novel missense variants were evaluated for conservation among species using TCoffee [15] and for pathogenic potential using standard prediction programs (i.e Polyphen [16], SIFT [17], PhD-SNP [18]). Novel synonymous and noncoding variants were evaluated for conservation among other mammalian species (bl2seq feature); novel synonymous variants were also evaluated for potential aberrant splicing (Human Splice Finder and ESE Finder) [19–21]. Finally, the frequencies of selected new variants were determined in healthy controls (195 Italian Caucasians, 100 North American Caucasians or 74 African Americans) by Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) or direct sequencing.

Screening for genomic rearrangements in HNF1B

We used Multiplex Ligation-Dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA) assay to look for structural variants in HNF1B [22]; we used the SALSA® MLPA kit P241-B1 MODY (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) designed to evaluate genes implicated in Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY). Mutations in HNF1B have been implicated in MODY-5, and as such primer pairs for the exons of HNF1B were present in this kit. We also used a second kit (SALSA® MLPA kit P297-B1 Microdeletion-2), with 7 probes on chromosome 17q12 to verify findings. Amplified samples were fractionated on a capillary sequencer (ABI Prism 3130X Genetic Analyzer, Applied Biosystems). MLPA data was normalized to a normal diploid control; a deletion and a duplication in HNF1B, previously characterized in the lab were incorporated into each run as positive controls. Finally, in the patient found to have a whole gene deletion in HNF1B, we verified the 5' and 3' breakpoints of the 17q12 microdeletion region by Quantitative PCR (QPCR). Primers were designed for the left and right flanks of the 1.4Mb microdeletion region, encompassing HNF1B among 19 other genes [23].

Results

We studied 73 CKiD patients with RHD, of whom 22 had family history of kidney disease (Table 1), and discovered pathogenic HNF1B and PAX2 mutations in seven individuals (10% of the cohort, Table 2)

Table 1.

Demographics of CKiD Cohort with diagnosis of aplasia, hypoplasia and/or dysplasia, with DNA samples stored (n=73).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age at entry into study (Yr, Range) | 9.3 (1.1–17.3) |

| Male (%) | 54.8 |

| Race (%) | |

| Caucasian | 71.2 |

| African American | 8.2 |

| American Indian | 2.7 |

| Asian | 1.4 |

| Other | 1.4 |

| >1 race excluding AA | 5.5 |

| >1 race including AA | 9.6 |

| Estimated GFR (ml/min/1.73m2, Range)* | 41.4 (18.7–131.7) |

| Systolic BP% (mmHg, Range)# | 59.2 (4.0–100.0) |

| Diastolic BP% (mmHg, Range)# | 61.4 (4.3–100.0) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2, Range) | 18.1 (11.8–28.1) |

| Family history of kidney disease (%) | 30.1 |

| of dialysis (Dx) (%) | 12.3 |

| of transplant (Tx) (%) | 5.5 |

eGFR based on new estimating formula derived by CKiD using Serum Cr, BUN and Cystatin C measured at first visit.

Blood pressure as percentile based on age, gender and height.

Table 2.

Mutations discovered in CKiD patients

| Gene | Exon | Base Change | Mutation | AA Change | Sex | Race | Age (y) | eGFR | FHx | Miscar |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HNF1B | 2 | c.444C>T | Missense | S148L | M | Cauc | 6.7 | 35 | - | + |

| HNF1B | 2 | c.543C>T | Nonsense | R181X | F | Cauc | 4.2 | 50 | - | - |

| HNF1B | 5 | c.1054_1055insA | Frameshift | Y352fsX352 | F | Cauc | 4.8 | 51.1 | +M | + |

| HNF1B | ALL | Chrom 17q12 | Whole gene deletion | NA | F | Cauc | 15.4 | 36.6 | - | - |

| PAX2 | 2 | c.71G>A | Missense | G24E | F | Cauc | 15.4 | 38 | +GP | - |

| PAX2 | 2 | c.69_70insG | Frameshift | G24fsX28 | M | Cauc | 7.7 | 29.6 | - | - |

| PAX2 | 5 | IVS4-1G>T | Splice site | NA | M | Cauc | 13.7 | 42.5 | +Cs | + |

Cauc= Caucasian. FHx= Family history (M=mother, GP= grandparent, Cs=cousin; kidney disease unknown in 3.) Miscar = Miscarriage in mother.

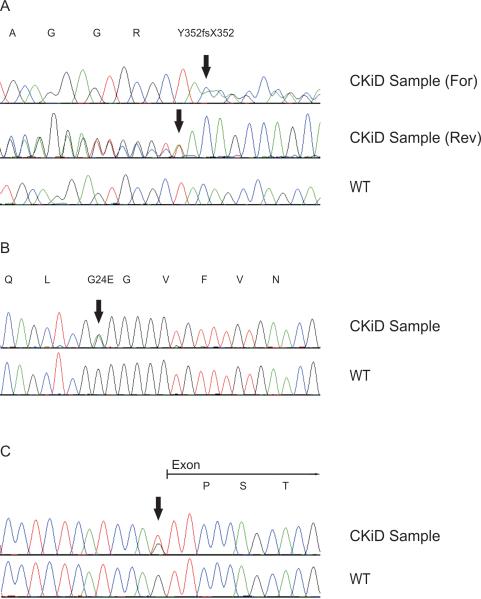

HNF1B Mutations

We detected one novel frameshift mutation in exon 5 where an insertion of an A shifts the reading frame from a tyrosine to a termination signal (c.1054_1055insA, Y352fsX352, Figure 1A). In a second patient, we found a missense mutation in exon 2 where a C>T transition results in a nonconservative amino acid change of a serine to a leucine (c.444C>T, pS148L). Not only is this mutation predicted to be pathogenic by multiple publicly available prediction programs (SIFT, Polyphen and PhD-SNP, Supplementary Table 1) but it has also been previously reported [16–18, 24]. A third patient had a nonsense mutation in exon 2 where a C>T transition results in the change of an arginine to a stop codon (c.543 C>T, pR181X). This mutation has also been previously reported [25]. Finally, one patient harbored ~1.4Mb deletion at the chromosome 17q12 locus, which includes the whole HNF1B gene detected by MLPA [22] (Supplementary Figure 1A). This result was confirmed using QPCR of the flanking regions of microdeletion on 17q12 (Supplementary Figure 1B, ref. [23]).

Figure 1.

Chromatograms of novel pathogenic mutations. The corresponding amino-acid sequences are indicated above each tracing. Arrows indicate the mutation.

A. Frameshift mutation: HNF1B c.1054_1055insA

B. Missense mutation: PAX2 c.71G>A

C. Splice site mutation: PAX2 (IVS4-1G>T)

For= Sequencing in the forward direction. Rev= Sequencing in the reverse direction. WT= wild type.

PAX2 Mutations

We discovered one patient with a novel missense mutation in exon 2 where a G>A transition results in a nonconservative amino acid change from glycine to a glutamic acid (c.71G>A, G24E, Figure 1B). This variant, which is located in a highly conserved region encoding the DNA binding domain of PAX2, is predicted to be pathogenic by SIFT, Polyphen and PhD-SNP (Supplementary Table 1, and Supplementary Figure 2A. Moreover, this sequence variant was not found in 350 Caucasian control chromosomes.

We also detected a novel splice site variant at the canonical acceptor splice site of exon 5 where a G>T transversion in the intron 4 at position -1 from exon 5 (IVS4–1G>T) is predicted to result in aberrant splicing (Figure 1C, ref. [26].

Finally, we identified a frameshift mutation in a polyguanine tract where an insertion of a guanine results in a shift in the reading frame to a termination signal (c.69_70insG, G24fsX28). This seven base pair polyguanine tract, in the DNA binding region of PAX2, has been reported previously to be highly susceptible to mutations due to contractions or expansions, likely due to slippage during DNA replication [14, 23, 27–31].

Rare HNF1B and PAX2 variants of unknown significance

We identified 22 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Of these, 12 have been previously annotated (10 noncoding and 2 synonymous coding, Supplementary Table 2) and ten were novel (9 noncoding and 1 synonymous coding, Supplementary Table 3). We determined the frequency of two rare PAX2 SNPs (IVS1–48G>C and c.889G>C, Leu>Leu) in healthy controls because both produced substitutions at nucleotides that were highly conserved in Pan troglodytes, Canis lupus familiaris, Mus musculus, Rattus norvegicus, and Gallus gallus (Supplementary Figure 2B and 2C.) Both SNPs were confirmed to be absent or extremely rare in the general population (frequency ≤ 0.003).

Clinical correlations

Of interest, all seven patients with pathogenic mutations were Caucasian (7 of 52), resulting in a 14% mutation rate in this subset. (Fisher exact p-value=0.08, for differences in mutation prevalence between Caucasians and non-Caucasians). We found no significant differences between the RHD patients with mutations compared to those without mutations, in relation to age, eGFR, systolic or diastolic blood pressure, BMI or progression of these factors at one year (Supplemental Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, we identified pathogenic HNF1B or PAX2 mutations in 14% of Caucasian individuals in a North American cohort of children with RHD. The mutation prevalence is consistent with previous studies of European and Japanese children with RHD [8–10, 27, 32]. Interestingly, we did not identify any mutations among non-Caucasian children. These differences may be due to variation in sampling and ascertainment methods, but may also reflect true differences in the prevalence of HNF1B and PAX2 mutations among different populations.

Horiwaka et al first discovered HNF1B mutations in patients with Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY5), an autosomal dominant form of diabetes mellitus frequently associated with renal cysts [33–36]. HNF1B is expressed in the kidney, pancreas, liver, gonads, gut, lung and thymus. HNF1B mutations produce diabetes at a mean age 17 – 25.8 yrs (30– 66%), genital malformations (12–62.5%), RHD, pancreas atrophy, hyperuricemia and abnormal liver function tests [11, 24, 25, 37, 38]. In women, genital malformations include bicornuate uterus, vaginal aplasia, or absent uterus [34, 39]. In men, asthenospermia, bilateral epidydimal cysts, and atresia of the vas deferens have been reported [25].

HNF1B is a critical regulator of a genetic cascade that is essential to controlling the proliferation and differentiation of renal tubular epithelial cells. It also controls the expression of the PKHD1 gene (the gene mutated in recessive polycystic kidney disease), accounting for the cystic renal phenotype in mutation carriers [40, 41]. The 1.4Mb region of chromosome 17 containing HNF1B is highly susceptible to copy number variation as it is flanked by areas of segmental duplications, which are sites for recurrent rearrangements [23, 42]. Accordingly, in the one patient in this study who harbored a heterozygous whole gene deletion in HNF1B, we found that the entire 1.4Mb critical region was deleted [23].

PAX2, a member of the “paired box” transcription factor gene family, is one of the earliest genes expressed during fetal kidney development, and is mutated in renal-coloboma syndrome (OMIM 120330, ref. [43, 44]). PAX2 is expressed in the optic and otic vesicles, the mesonephros (which later give rise to the male and female genital tracts), kidney and parts of the central nervous system [45]. PAX2 mutations lead to multiorgan defects including RHD (68%), ocular abnormalities in nearly 100% of children, high frequency hearing loss (16%) which can be subtle and often missed, and associated vesicoureteral reflux (26%) [30] [27]. The typical ocular association with renal-coloboma syndrome is bilateral optic nerve coloboma; however, ocular manifestations have also included optic nerve or disc dysplasia, retinal coloboma, micropthalmia, morning glory anomaly, optic nerve cysts, scleral staphloma, myopia, nystagmus and cataracts [46, 47]. Visual acuity is variable, ranging from near normal to severely impaired, with a reduction in vision acuity of one or both eyes in 75% of affected individuals [46, 47].

There are several important clinical implications from our findings. Although HNF1B and PAX2 mutations classically affect multiple organs, many organ defects may be subtle or subclinical, complicating diagnosis by standard clinical methods. As illustrated in this study, the patients with PAX2 or HNF1B mutations were not readily distinguishable from the patients with no mutations. Mutation screening can therefore provide the correct diagnosis, and also motivate surveillance for extra-renal manifestations and potential future complications. Detailed information about extrarenal manifestations is now being collected in the follow-up phase of the CKiD study to pursue these findings. Our data, in combination with prior studies, provide a strong rationale for mutation screening of all children with RHD. Clinical genetic testing is available for PAX2 or HNF1B (information available at Genetics Home Reference, http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/).

Mutation identification may aid in genetic counseling. Previous reports have indicated that as many as half of the mutations in HNF1B and PAX2 occur de novo [8, 9, 11]. Knowing whether the mutation was inherited or occurred de novo would therefore have consequences for screening siblings as well as advising parents who would like to conceive further [48]. In this cohort, only one child reported a family history of RHD (in a cousin), but we did not find any pathogenic mutations in this patient. However, it is noteworthy that there was a history of miscarriage in the mothers of two patients with HNF1B mutations, suggesting that these mothers may have uterine abnormaiities and be mutation carriers [39].

The majority of children (particularly non-Caucasians) in the CKiD cohort did not have mutations in HNF1B and PAX2; mutations in other genes such as SALL1, SIX1, EYA1 are also exceeding rare in all reported studies [8–10, 27, 32]. These data suggest that there are other, yet undiscovered genes that may cause RHD. In the past few years, the introduction of high-density oligonucleotide arrays and Next-gen sequencing methods has enabled detection of rare mutations associated with human disease, leading to the identification of new clinical entities. These methods have been particularly successful in studies of developmental disorders. For example, studying patients with multiple complex malformations, Unger et al found a mutation in the cyclin family member FAM58A to be the cause of an X-linked dominant disorder characterized by syndactyly, telecanthus and anogenital and renal malformations (“STAR syndrome”[49]. Similarly, exome sequencing has recently identified mutations in MLL2 as a cause of Kabuki syndrome, a multiorgan developmental disorder [50]. Our findings thus support application of these novel methodologies to detect novel genes producing RHD in the CKiD cohort.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients for their participation in this study. We thank Catarina Quinzii and Michio Hirano at The H. Houston Merritt Center for Neuromuscular and Mitochondrial Disorders at Columbia University for assistance with MLPA. This study was supported by 1R01DK080099 (AGG). Rosemary Thomas is supported by the T32 NIH training grant. Simone Sanna-Cherchi is supported by the American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (0930151N) and the American Society of Nephrology Career Development Grant. Data in this manuscript were collected by the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children prospective cohort study (CKiD) with clinical coordinating centers (Principal Investigators) at Children's Mercy Hospital and the University of Missouri – Kansas City (Bradley Warady, MD) and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (Susan Furth, MD, PhD), central laboratory (Principal Investigator) at the Department of Pediatrics, University of Rochester Medical Center (George Schwartz, MD), and data coordinating center (Principal Investigator) at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (Alvaro Muñoz, PhD). The CKiD is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, with additional funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U01 DK066143, U01 DK066174, U01 DK082194, U01 DK066116). The CKiD website is located at http://www.statepi.jhsph.edu.

Footnotes

Wed resources:

NAPRTCS 2008 Annual Report:

https://web.emmes.com/study/ped/annlrept/Annual%20Report%20-2008.pdf

Genetics Home Reference: http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/

http://uswest.ensembl.org/index.html

References

- 1.Warady BA, Chadha V. Chronic kidney disease in children: the global perspective. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:1999–2009. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0410-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hiraoka M, Tsukahara H, Ohshima Y, Kasuga K, Ishihara Y, Mayumi M. Renal aplasia is the predominant cause of congenital solitary kidneys. Kidney Int. 2002;61:1840–1844. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winyard P, Chitty LS. Dysplastic kidneys. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;13:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klaassen I, Neuhaus TJ, Mueller-Wiefel DE, Kemper MJ. Antenatal oligohydramnios of renal origin: long-term outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:432–439. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ismaili K, Schurmans T, Wissing KM, Hall M, Van Aelst C, Janssen F. Early prognostic factors of infants with chronic renal failure caused by renal dysplasia. Pediatr Nephrol. 2001;16:260–264. doi: 10.1007/s004670000539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roodhooft AM, Birnholz JC, Holmes LB. Familial nature of congenital absence and severe dysgenesis of both kidneys. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1341–1345. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198405243102101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanna-Cherchi S, Caridi G, Weng PL, Scolari F, Perfumo F, Gharavi AG, Ghiggeri GM. Genetic approaches to human renal agenesis/hypoplasia and dysplasia. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:1675–1684. doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0479-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heidet L, Decramer S, Pawtowski A, Moriniere V, Bandin F, Knebelmann B, Lebre AS, Faguer S, Guigonis V, Antignac C, Salomon R. Spectrum of HNF1B mutations in a large cohort of patients who harbor renal diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1079–1090. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06810909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber S, Moriniere V, Knuppel T, Charbit M, Dusek J, Ghiggeri GM, Jankauskiene A, Mir S, Montini G, Peco-Antic A, Wuhl E, Zurowska AM, Mehls O, Antignac C, Schaefer F, Salomon R. Prevalence of mutations in renal developmental genes in children with renal hypodysplasia: results of the ESCAPE study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2864–2870. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ulinski T, Lescure S, Beaufils S, Guigonis V, Decramer S, Morin D, Clauin S, Deschenes G, Bouissou F, Bensman A, Bellanne-Chantelot C. Renal phenotypes related to hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta (TCF2) mutations in a pediatric cohort. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:497–503. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005101040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edghill EL, Oram RA, Owens M, Stals KL, Harries LW, Hattersley AT, Ellard S, Bingham C. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta gene deletions--a common cause of renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:627–635. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furth SL, Cole SR, Moxey-Mims M, Kaskel F, Mak R, Schwartz G, Wong C, Munoz A, Warady BA. Design and methods of the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children (CKiD) prospective cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1006–1015. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01941205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz GJ, Furth SL. Glomerular filtration rate measurement and estimation in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:1839–1848. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stenson PD, Ball EV, Howells K, Phillips AD, Mort M, Cooper DN. The Human Gene Mutation Database: providing a comprehensive central mutation database for molecular diagnostics and personalized genomics. Hum Genomics. 2009;4:69–72. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-4-2-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J. T-Coffee: A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:205–217. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramensky V, Bork P, Sunyaev S. Human non-synonymous SNPs: server and survey. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3894–3900. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capriotti E, Calabrese R, Casadio R. Predicting the insurgence of human genetic diseases associated to single point protein mutations with support vector machines and evolutionary information. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2729–2734. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang C, Li WH, Krainer AR, Zhang MQ. RNA landscape of evolution for optimal exon and intron discrimination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5797–5802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801692105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desmet FO, Hamroun D, Lalande M, Collod-Beroud G, Claustres M, Beroud C. Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cartegni L, Wang J, Zhu Z, Zhang MQ, Krainer AR. ESEfinder: A web resource to identify exonic splicing enhancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3568–3571. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen Y, Wu BL. Designing a simple multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) assay for rapid detection of copy number variants in the genome. J Genet Genomics. 2009;36:257–265. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(08)60113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mefford HC, Clauin S, Sharp AJ, Moller RS, Ullmann R, Kapur R, Pinkel D, Cooper GM, Ventura M, Ropers HH, Tommerup N, Eichler EE, Bellanne-Chantelot C. Recurrent reciprocal genomic rearrangements of 17q12 are associated with renal disease, diabetes, and epilepsy. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1057–1069. doi: 10.1086/522591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edghill EL, Bingham C, Ellard S, Hattersley AT. Mutations in hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta and their related phenotypes. J Med Genet. 2006;43:84–90. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.032854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bellanne-Chantelot C, Chauveau D, Gautier JF, Dubois-Laforgue D, Clauin S, Beaufils S, Wilhelm JM, Boitard C, Noel LH, Velho G, Timsit J. Clinical spectrum associated with hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta mutations. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:510–517. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cartegni L, Chew SL, Krainer AR. Listening to silence and understanding nonsense: exonic mutations that affect splicing. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:285–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amiel J, Audollent S, Joly D, Dureau P, Salomon R, Tellier AL, Auge J, Bouissou F, Antignac C, Gubler MC, Eccles MR, Munnich A, Vekemans M, Lyonnet S, Attie-Bitach T. PAX2 mutations in renal-coloboma syndrome: mutational hotspot and germline mosaicism. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:820–826. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porteous S, Torban E, Cho NP, Cunliffe H, Chua L, McNoe L, Ward T, Souza C, Gus P, Giugliani R, Sato T, Yun K, Favor J, Sicotte M, Goodyer P, Eccles M. Primary renal hypoplasia in humans and mice with PAX2 mutations: evidence of increased apoptosis in fetal kidneys of Pax2(1Neu) +/− mutant mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1–11. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schimmenti LA, Shim HH, Wirtschafter JD, Panzarino VA, Kashtan CE, Kirkpatrick SJ, Wargowski DS, France TD, Michel E, Dobyns WB. Homonucleotide expansion and contraction mutations of PAX2 and inclusion of Chiari 1 malformation as part of renal-coloboma syndrome. Hum Mutat. 1999;14:369–376. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(199911)14:5<369::AID-HUMU2>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eccles MR, Schimmenti LA. Renal-coloboma syndrome: a multi-system developmental disorder caused by PAX2 mutations. Clin Genet. 1999;56:1–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.1999.560101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schimmenti LA, Cunliffe HE, McNoe LA, Ward TA, French MC, Shim HH, Zhang YH, Proesmans W, Leys A, Byerly KA, Braddock SR, Masuno M, Imaizumi K, Devriendt K, Eccles MR. Further delineation of renal-coloboma syndrome in patients with extreme variability of phenotype and identical PAX2 mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:869–878. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakayama M, Nozu K, Goto Y, Kamei K, Ito S, Sato H, Emi M, Nakanishi K, Tsuchiya S, Iijima K. HNF1B alterations associated with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:1073–1079. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1454-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horikawa Y, Iwasaki N, Hara M, Furuta H, Hinokio Y, Cockburn BN, Lindner T, Yamagata K, Ogata M, Tomonaga O, Kuroki H, Kasahara T, Iwamoto Y, Bell GI. Mutation in hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 beta gene (TCF2) associated with MODY. Nat Genet. 1997;17:384–385. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindner TH, Njolstad PR, Horikawa Y, Bostad L, Bell GI, Sovik O. A novel syndrome of diabetes mellitus, renal dysfunction and genital malformation associated with a partial deletion of the pseudo-POU domain of hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2001–2008. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.11.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kolatsi-Joannou M, Bingham C, Ellard S, Bulman MP, Allen LI, Hattersley AT, Woolf AS. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta: a new kindred with renal cysts and diabetes and gene expression in normal human development. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2175–2180. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12102175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montoli A, Colussi G, Massa O, Caccia R, Rizzoni G, Civati G, Barbetti F. Renal cysts and diabetes syndrome linked to mutations of the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 beta gene: description of a new family with associated liver involvement. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:397–402. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.34538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bingham C, Hattersley AT. Renal cysts and diabetes syndrome resulting from mutations in hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:2703–2708. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zaffanello M, Brugnara M, Franchini M, Fanos V. TCF2 gene mutation leads to nephro-urological defects of unequal severity: an open question. Med Sci Monit. 2008;14:RA78–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oram RA, Edghill EL, Blackman J, Taylor MJ, Kay T, Flanagan SE, Ismail-Pratt I, Creighton SM, Ellard S, Hattersley AT, Bingham C. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta (HNF1B) gene are common with combined uterine and renal malformations but are not found with isolated uterine malformations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:364, e361–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gresh L, Fischer E, Reimann A, Tanguy M, Garbay S, Shao X, Hiesberger T, Fiette L, Igarashi P, Yaniv M, Pontoglio M. A transcriptional network in polycystic kidney disease. EMBO J. 2004;23:1657–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hiesberger T, Bai Y, Shao X, McNally BT, Sinclair AM, Tian X, Somlo S, Igarashi P. Mutation of hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta inhibits Pkhd1 gene expression and produces renal cysts in mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:814–825. doi: 10.1172/JCI20083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharp AJ, Hansen S, Selzer RR, Cheng Z, Regan R, Hurst JA, Stewart H, Price SM, Blair E, Hennekam RC, Fitzpatrick CA, Segraves R, Richmond TA, Guiver C, Albertson DG, Pinkel D, Eis PS, Schwartz S, Knight SJ, Eichler EE. Discovery of previously unidentified genomic disorders from the duplication architecture of the human genome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1038–1042. doi: 10.1038/ng1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weaver RG, Cashwell LF, Lorentz W, Whiteman D, Geisinger KR, Ball M. Optic nerve coloboma associated with renal disease. Am J Med Genet. 1988;29:597–605. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320290318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanyanusin P, Schimmenti LA, McNoe LA, Ward TA, Pierpont ME, Sullivan MJ, Dobyns WB, Eccles MR. Mutation of the PAX2 gene in a family with optic nerve colobomas, renal anomalies and vesicoureteral reflux. Nat Genet. 1995;9:358–364. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dressler GR, Deutsch U, Chowdhury K, Nornes HO, Gruss P. Pax2, a new murine paired-box-containing gene and its expression in the developing excretory system. Development. 1990;109:787–795. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.4.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schimmenti LA, Manligas GS, Sieving PA. Optic nerve dysplasia and renal insufficiency in a family with a novel PAX2 mutation, Arg115X: further ophthalmologic delineation of the renal-coloboma syndrome. Ophthalmic Genet. 2003;24:191–202. doi: 10.1076/opge.24.4.191.17229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheong HI, Cho HY, Kim JH, Yu YS, Ha IS, Choi Y. A clinico-genetic study of renal coloboma syndrome in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:1283–1289. doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0525-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martinovic-Bouriel J, Benachi A, Bonniere M, Brahimi N, Esculpavit C, Morichon N, Vekemans M, Antignac C, Salomon R, Encha-Razavi F, Attie-Bitach T, Gubler MC. PAX2 mutations in fetal renal hypodysplasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:830–835. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Unger S, Bohm D, Kaiser FJ, Kaulfuss S, Borozdin W, Buiting K, Burfeind P, Bohm J, Barrionuevo F, Craig A, Borowski K, Keppler-Noreuil K, Schmitt-Mechelke T, Steiner B, Bartholdi D, Lemke J, Mortier G, Sandford R, Zabel B, Superti-Furga A, Kohlhase J. Mutations in the cyclin family member FAM58A cause an X-linked dominant disorder characterized by syndactyly, telecanthus and anogenital and renal malformations. Nat Genet. 2008;40:287–289. doi: 10.1038/ng.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ng SB, Bigham AW, Buckingham KJ, Hannibal MC, McMillin MJ, Gildersleeve HI, Beck AE, Tabor HK, Cooper GM, Mefford HC, Lee C, Turner EH, Smith JD, Rieder MJ, Yoshiura K, Matsumoto N, Ohta T, Niikawa N, Nickerson DA, Bamshad MJ, Shendure J. Exome sequencing identifies MLL2 mutations as a cause of Kabuki syndrome. Nat Genet. 2010;42:790–793. doi: 10.1038/ng.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.