Abstract

The role of autophagy, a catabolic lysosome-dependent pathway, has recently been recognized in a variety of disorders, including Pompe disease, which results from a deficiency of the glycogen-degrading lysosomal hydrolase acid-alpha glucosidase (GAA). Skeletal and cardiac muscle are most severely affected by the progressive expansion of glycogen-filled lysosomes. In both humans and an animal model of the disease (GAA KO), skeletal muscle pathology also involves massive accumulation of autophagic vesicles and autophagic buildup in the core of myofibers, suggesting an induction of autophagy. Only when we suppressed autophagy in the skeletal muscle of the GAA KO mice did we realize that the excess of autophagy manifests as a functional deficiency. This failure of productive autophagy is responsible for the accumulation of potentially toxic aggregate-prone ubiquitinated proteins, which likely cause profound muscle damage in Pompe mice. Also, by generating muscle-specific autophagy-deficient wild-type mice, we were able to analyze the role of autophagy in healthy skeletal muscle.

Keywords: Pompe disease, lysosome, muscle-specific autophagy deficiency, protein inclusions

The hallmark of macroautophagy (referred to as autophagy), a catabolic lysosome-dependent process responsible for the degradation of intracellular components, is the formation of a double-membrane autophagosome, which separates the material destined for lysosomal degradation from the rest of the cytoplasm (reviewed in ref. 1–3). The question of how to interpret the changes in autophagosome number in a particular system has recently become a hot topic in the field of autophagy.4-7 Accumulation of autophagic vacuoles could indicate an upregulation of autophagy or defects in autophagosome/lysosome fusion (incomplete autophagic flux). In a paper published in Human Molecular Genetics we demonstrate that both processes are at play in Pompe disease, a debilitating muscle disorder caused by a deficiency of the glycogen-degrading lysosomal enzyme acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA). What makes this combination of induced autophagy and incomplete flux in Pompe muscle more complex is that it occurs only in some muscle fiber types and is limited to some parts of muscle cells.

In Pompe disease, enlarged glycogen-filled lysosomes accumulate in multiple tissues, eventually resulting in organ destruction. Severe skeletal myopathy and cardiomyopathy are fatal in infants who succumb to the disease within the first year of life. Cardiac muscle is spared in patients with milder late-onset forms, but progressive skeletal muscle weakness eventually leads to premature death due to respiratory insufficiency.8 Our recent studies in a mouse model of Pompe disease have shown that in addition to the progressive enlargement of glycogen-filled lysosomes, extensive autophagic accumulation in fast but not in slow muscle fibers contributes significantly to muscle destruction.9,10 Not only does this autophagy-related pathology disrupt the contractile apparatus in the fibers, it interferes with enzyme replacement therapy by preventing the efficient delivery of the recombinant GAA to the lysosomes.11,12 This dramatic and disruptive autophagic accumulation is also observed in Pompe patients.13

To evaluate the relative contribution of autophagy and intralysosomal glycogen storage to muscle wasting in Pompe disease, we generated GAA KO mice, in which Atg5, a critical gene in autophagosome formation,14 is inactivated specifically in skeletal muscle (AD-GAA KO). These mice were also designed to address the question of whether macroautophagy is the route by which glycogen reaches the lysosomes in skeletal muscle. Autophagic delivery of glycogen to lysosomes occurs in neonatal liver tissues (reviewed in ref. 15 and 16). Earlier studies suggest that autophagic degradation and rapid mobilization of glycogen not only in liver, but also in skeletal muscle, is an important source of energy in the first critical period of extrauterine life in newborn rats.17 If indeed glycogen reaches the lysosomes by the autophagic pathway, then the suppression of autophagy might rescue the Pompe phenotype by preventing glycogen accumulation in this organelle.

However, we quickly realized that the accumulation of lysosomal glycogen in AD-GAA KO mice proceeded despite the suppression of autophagy. This indicates that macroautophagy is not the major route of glycogen delivery to the lysosome in muscle; microautophagy, the direct transport of substrates to the lysosome by invagination of the lysosomal membrane, may be a plausible alternative. Furthermore, far from rescuing the phenotype of the GAA KO mice by preventing lysosomal glycogen accumulation, the suppression of autophagy exacerbated muscle wasting and significantly shortened the life span of the mice.

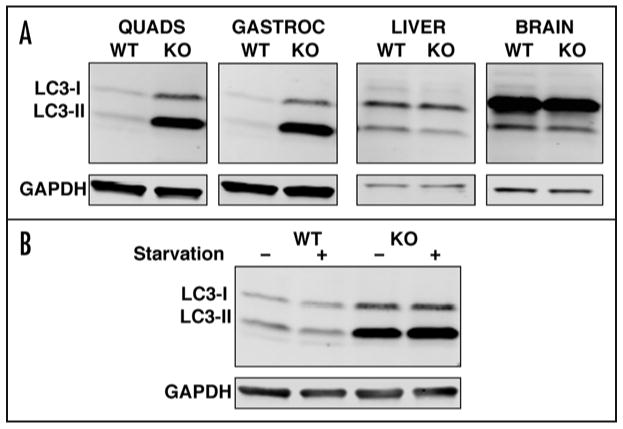

This outcome questioned the assumption that autophagy is induced in the GAA KO mice. However, the autophagic accumulation in the core of fast GAA KO fibers, a significant upregulation of genes involved in the formation and maturation of autophagosomes (class III PI3-kinase, Beclin 1, Atg12 and Gabarap),18 as well as a striking increase in the total amount of LC3 in Pompe muscle, all indicate that indeed autophagy is induced. Furthermore, our most recent observations indicate that this induction is specific to skeletal muscle since no changes in the level of LC3 were observed in the GAA KO liver and brain, two organs that also accumulate lysosomal glycogen (Fig. 1A). Paradoxically, then, the phenotypic defect in fast fibers arises not from an induction but rather from a functional deficiency of autophagy. Starvation experiments provided a clue regarding this deficiency. In fast GAA KO muscle, unlike wild-type muscle, the amount of LC3-II, an autophagosomal marker,19 after starvation is greater than the baseline level (Fig. 1B), suggesting that there is a block in autophagosomal turnover in the diseased muscle. The direct evidence of an autophagic block comes from experiments showing the accumulation of autophagic substrates, such as ubiquitinated (Ub) proteins and p62/SQSTM1.20-22 The accumulation of Ub-proteins in the GAA KO preceded the development of clinical symptoms, increased with age, and was most dramatic for nonsoluble proteins, suggesting that the formation of ubiquitin-positive protein aggregates parallels the progression of the disease.

Figure 1.

(A) Basal level of autophagy in fast muscles (quadriceps and white gastrocnemius), liver, and brain from 5-month-old wild-type and GAA KO mice. Western blotting of protein lysates with LC3 antibody shows a dramatic increase in the levels of both LC3-I and LC3-II in muscle, but not in liver or brain from GAA KO mice. (B) Western blotting of protein lysates (white gastrocnemius) with LC3 antibody from 1-month old wild-type and GAA KO mice after 48-hour starvation. Analysis of the amount of LC3-II by densitometry showed an ∼60% increase in the GAA KO after starvation. GAPDH serves as a loading control.

An unusual feature of this functional deficiency is that it manifests in only a part of the fast GAA KO fibers as shown, for example, by the confinement of the potentially toxic Ub-protein inclusions to limited areas in the core of the fibers. In contrast, the ubiquitin-positive inclusions in fast AD-GAA KO fibers are dispersed throughout the fibers, and are more numerous than in GAA KO muscle. Thus, the additional burden imposed by complete genetic deficiency of autophagy exaggerates the problem already present in the GAA KO and exacerbates the phenotypic expression of the disease.

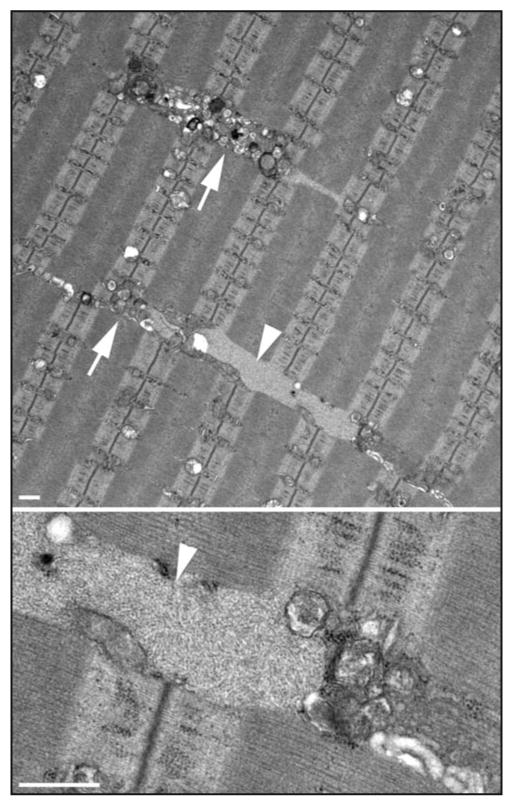

Finally, we also analyzed muscle-specific autophagy-deficient wild-type mice (AD-WT); this strain provided an opportunity to explore the role of autophagy in healthy skeletal muscle, of which little is known. These mice remained clinically unaffected during seven months of observation despite the mild atrophy of the fast fibers, and the accumulation of autophagic substrates (Fig. 2). This accumulation is also observed in autophagy-deficient brain and liver,20,21,23 thus illustrating a remarkable similarity among diverse tissues in their response to the lack of autophagy. Of interest is the finding of an increase in the lysosomal size and density in AD-WT fast fibers (Fig. 2), possibly in an attempt to compensate for the loss of macroautophagy by the upregulation of chaperone-mediated autophagy. Also, there is a strikingly altered distribution and proliferation of microtubules in the AD-WT compared to the wild type, indicating that intact autophagy is essential for the normal disposition of microtubules in skeletal muscle.

Figure 2.

Electron microscopy images of fast muscle (psoas) from a 5-month-old muscle-specific autophagy-deficient wild-type mouse. The upper image shows clusters of vesicles (arrows), which likely represent lysosomes; also shown are electron-light, irregularly shaped inclusions (arrowhead), which likely represent polyubiquitinated protein aggregates. A filamentous inclusion (arrowhead) is clearly seen at higher magnification (lower). Bar: 0.5 micron.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Judith Melki (Molecular Neurogenetics Laboratory, INSERM, U798, Evry, France) and Dr. Steven Burden (New York University Medical School, NY) for the HSA-Cre: Atg5flox/+ mice.

Financial support: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Takikita was supported in part by a CRADA between the NIH and Genzyme Corporation (Framingham, MA).

Footnotes

Addendum to: Raben N, Hill V, Shea L, Takikita S, Baum R, Mizushima N, Ralston E, Plotz P. Suppression of autophagy in skeletal muscle uncovers the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and their potential role in muscle damage in Pompe disease.

References

- 1.Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004;6:463–77. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–75. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: from phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:931–7. doi: 10.1038/nrm2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klionsky DJ, Abeliovich H, Agostinis P, Agrawal DK, Aliev G, Askew DS, Baba M, Baehrecke EH, Bahr BA, Ballabio A, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy. 2008;4:151–75. doi: 10.4161/auto.5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T. How to interpret LC3 immunoblotting. Autophagy. 2007;3:542–45. doi: 10.4161/auto.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanida I, Minematsu-Ikeguchi N, Ueno T, Kominami E. Lysosomal turnover, but not a cellular level, of endogenous LC3 is a marker for autophagy. Autophagy. 2005;1:84–91. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.2.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuma A, Matsui M, Mizushima N. LC3, an autophagosome marker, can be incorporated into protein aggregates independent of autophagy: caution in the interpretation of LC3 localization. Autophagy. 2007;3:323–8. doi: 10.4161/auto.4012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engel Andrew G, Hirschhorn Rochelle, Huie Maryanne L. In: Myology. Engel Andrew G, Franzini-Armstrong Clara., editors. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2003. pp. 1559–86. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukuda T, Ewan L, Bauer M, Mattaliano RJ, Zaal K, Ralston E, Plotz PH, Raben N. Dysfunction of endocytic and autophagic pathways in a lysosomal storage disease. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:700–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.20807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukuda T, Roberts A, Plotz PH, Raben N. Acid alpha-glucosidase deficiency (Pompe disease) Curr Neurl Neurosci. 2007;7:71–7. doi: 10.1007/s11910-007-0024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raben N, Fukuda T, Gilbert AL, de Jong D, Thurberg BL, Mattaliano RJ, Meikle P, Hopwood JJ, Nagashima K, Nagaraju K, Plotz PH. Replacing acid alpha-glucosidase in Pompe disease: recombinant and transgenic enzymes are equipotent, but neither completely clears glycogen from type II muscle fibers. Mol Ther. 2005;11:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuda T, Ahearn M, Roberts A, Mattaliano RJ, Zaal K, Ralston E, Plotz PH, Raben N. Autophagy and mistargeting of therapeutic enzyme in skeletal muscle in Pompe disease. Mol Ther. 2006;14:831–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raben N, Takikita S, Pittis MG, Bembi B, Marie SKN, Roberts A, Page L, Kishnani PS, Schoser BGH, Chien YH, Ralston E, Nagaraju K, Plotz PH. Deconstructing Pompe disease by analyzing single muscle fibers. Autophagy. 2007;3:546–52. doi: 10.4161/auto.4591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. Autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. Cell Struct Funct. 2002;27:421–9. doi: 10.1247/csf.27.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotoulas OB, Kalamidas SA, Kondomerkos DJ. Glycogen autophagy in glucose homeostasis. Pathol Res Pract. 2006;202:631–8. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiaffino S, Mammucari C, Sandri M. The role of autophagy in neonatal tissues: Just a response to amino acid starvation? Autophagy. 2008;4:727–30. doi: 10.4161/auto.6143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiaffino S, Hanzlikova V. Autophagic degradation of glycogen in skeletal muscles of the newborn rat. J Cell Biol. 1972;52:41–51. doi: 10.1083/jcb.52.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukuda T, Roberts A, Ahearn M, Zaal K, Ralston E, Plotz PH, Raben N. Autophagy and lysosomes in Pompe disease. Autophagy. 2006;2:318–20. doi: 10.4161/auto.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19:5720–8. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komatsu M, Waguri S, Chiba T, Murata S, Iwata J, Tanida I, Ueno T, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Kominami E, Tanaka K. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441:880–4. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hara T, Nakamura K, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakahara Y, Suzuki-Migishima R, Yokoyama M, Mishima K, Saito I, Okano H, Mizushima N. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441:885–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun JA, Outzen H, Øvervatn A, Bjørkøy G, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Komatsu M, Waguri S, Ueno T, Iwata J, Murata S, Tanida I, Ezaki J, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Uchiyama Y, Kominami E, Tanaka K, Chiba T. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:425–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]