Abstract

Background

Swelling, pain, and pruritus are the most relevant symptoms after insect bites/stings. Glucocorticoids and antihistamines are well established in insect sting treatment. Bite Away® is a CE-certified medical device of class 2A (noninvasive device intended for administration to the body, which exchanges energy with the patient in a therapeutic manner) to reduce swelling, pruritus, and pain after insect bites/stings via non-invasive administration of concentrated heat to the skin. We therefore performed a prospective, non-interventional, single-arm cohort study with 146 volunteers using the visual analog scale (VAS) for insect bites/stings to study the reduction of swelling, pruritus, and pain. Demographic data, time from insect sting to treatment, number and duration of administrations of concentrated heat, relevant symptoms, and the development of a VAS score of swelling, pruritus, and pain on baseline, after 2, 5, and 10 minutes after administration, were registered.

Results

In total 146 subjects with a mean age of 29.4 ± 20.7 years (range 2–81) were enrolled in the study. Ninety-three (63.7%) of the subjects were stung by wasps, 33 (22.6%) of the subjects were bitten by mosquitoes, and eight suffered bee stings (5.3%). VAS score swelling decreased with statistical significance after the use of Bite Away® from 4 before treatment to 2 and 1 after 2–5 and 10 minutes, respectively. VAS pain score was 6 before treatment, 2 after 2 minutes, 1 after 5 minutes, and 0 after 10 minutes (median). VAS pruritus score was only available for 52 (35.2%) of the patients. The score decreased from 5 before treatment, to 2 after 2 minutes, and 0 after 5 and 10 minutes.

Conclusions

Locally administrated concentrated heat leads to fast amelioration of symptoms. Usually an absence of symptoms is noticeable 10 minutes after administration. Pain reduction is the dominant effect. Compared with alternatives of pruritus and pain treatment after insect bites/stings, Bite Away® seems to be the fastest treatment option available.

Keywords: insect bites/stings, swelling, pain, pruritus, concentrated heat, VAS

Introduction

Swelling, pruritus, and pain are the most relevant symptoms after insect bites/stings.1 Insects inject a pruritic and/or pain-inducing substance through the epidermis into the dermis with their saliva. Allergic reactions are mediated by immunoglobulins that target specific antigens in hymenopteran venoms.2 A cascade of activation of histamine receptors, followed by neurogene inflammation and edema, erythema, and itching is induced.3,4 The prevalence of stinging insect hypersensitivity reactions ranges from 0.4% to 3.3%5–7 and causes approximately 40 to 100 deaths in the US each year.8,9 Insect stings are regularly treated with removal of the stingers, cooling, and over-the-counter medications. Most common are topical glucocorticoids, and topical or systemic antihistamines. Only in cases of acute anaphylaxis is epinephrine an essential drug for emergency therapy.8,10,11 Several domestic remedies are used such as onions, lemons, saliva, vinegar, or tea tree oil with no evidence for effectiveness in insect sting therapy.

Bite Away® (RIEMSER Arzneimittel AG, Greifswald, Germany) is a CE-certified medical device of class 2A (non-invasive device intended for administration to the body, which exchanges energy with the patient in a therapeutic manner) for noninvasive administration to the skin to reduce swelling, pruritus, and pain after insect bites/stings. Its microchip- controlled time-heat-constant guarantees a maximum temperature of 51°C on a 38.5-mm2 gold-covered plate for either 3 or 6 seconds. Patients individually choose the 3-second button (this modus is recommended for anxious people or children) or the 6-second button (for anybody else, who can accept the duration of treatment), which activates the device.

So far, the effects of concentrated heat on skin after insect bites/stings have not been evaluated in any single study. We therefore performed a prospective, non-interventional, single-arm cohort study with 146 volunteers to study the reduction of the visual analog scale (VAS) score of swelling, pain, and pruritus after insect bites/stings at German beaches and bathing lakes.

Methods

Bite Away® was used in collaboration with the German Life Saving Federation and the German Red Cross, section Baywatch (Wasserwacht), near bathing lakes and beaches in north east Germany. First aiders received a detailed briefing on insect bites/stings management with Bite Away®, handling of patient recruitment, and documentation within the questionnaire by Lutz Fischer, MD. The observation period was from March to October 2009.

Patient selection

Lifeguards on their lifeguard towers or headquarters were the first contact persons to treat insect bites/stings. Because Bite Away® was used in routine treatment at all study sites, every case of an insect sting was enrolled in this study after provision of a brief explanation to the patient, and the patient giving informed consent. There was no selection of subjects with a known hypersensitivity to insect bites/stings. A questionnaire created in advance was filled in by the first aider. Demographic data, time from insect sting to treatment, number and duration of administrations, relevant symptoms, and the development of VAS for swelling, pruritus, and pain on baseline, 2, 5, and 10 minutes after administration, were registered. Patients voted their individual swelling, pruritus, and pain perception on a scale of 0 (none) to 10 (worst imaginable perception). In general, children selected the 3-second modus, and adults selected the 6-second modus. Depending on the area of the bites/stings and the pain perception of the patient, both first aider and patient made the decision on the number of treatments.

Data management

An Excel spreadsheet was used for single data entry. The structure of the database was adapted from the questionnaire. All analyses were performed using SAS software (v 9.2; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Data are expressed as mean, standard deviation, median (with interquartile range [IQR]), minimum and maximum. Comparisons of VAS scores were evaluated using the Wilcoxon test (P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant). Statistical tests only have descriptive character. For missing data the last observation carried forward method was used.

Results

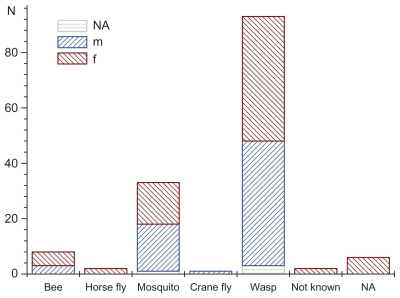

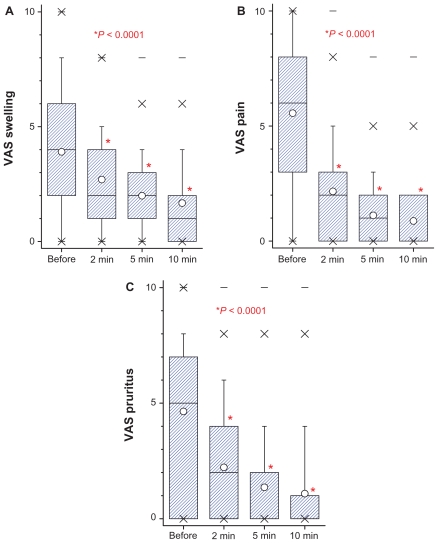

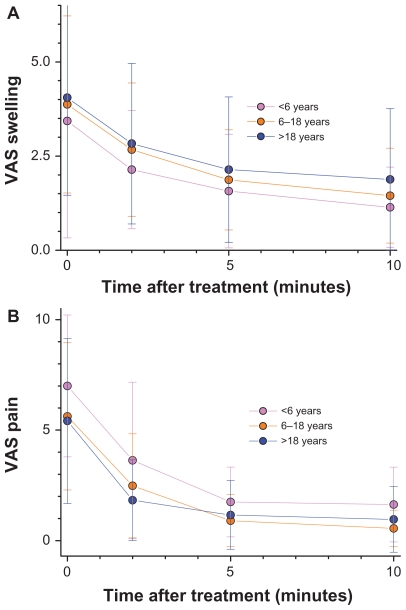

In total, 146 subjects (67 male, 72 female: for five subjects sex was not specified) were enrolled in the study. The mean age of the patients was 29.4 ± 20.7 years (range 2–81 years). Wasp stings were observed in 93 (63.7%) subjects, mosquito stings in 33 (22.6%) subjects, and bee stings in 8 (5.3%) subjects (Figure 1). Among all the patients, 108 (74%) had swelling, 85 (58.2%) had pain, 84 (57.5%) had erythema (reddening of the skin), 52 (35.6%) had pruritus, and two (1.4%) had dyspnea. The frequency of symptoms as well as the number and duration of Bite Away® administrations are all listed in Table 1. In general, patients contacted the lifeguards immediately (72.6% of patients within 15 minutes). Although swelling was registered for 108 patients, only 95 data sets for a VAS score swelling were available. VAS score swelling decreased with statistical significance after the use of Bite Away® from 4 before treatment to 2 and 1 after 2–5 and 10 minutes, respectively (Figure 2A). VAS pain score was 6 before treatment, 2 after 2 minutes, 1 after 5 minutes, and 0 after 10 minutes (Figure 2B). By observing the pain perception of the subgroup of patients with wasp bites, an 86% reduction of VAS was visible (VAS 7.32 ± 2.45 before treatment to VAS 1.03 ± 1.21; P < 0.0001). Because of the high rate of wasp stings, VAS pruritus score was only available for 52 (35.2%) patients. Stratifying the cohort by age, there was a comparable reduction of VAS score swelling over time for children (under 6 years), for adolescents (from 6 to 18 years), and for adults (above 18 years) (Figure 3A and B)..

Figure 1.

Frequency and type of insect bite/sting presented for subgroups of male (m) and female (f).

Abbreviation: NA, data not available.

Table 1.

Symptoms of insect bites/stings and mode of administration of Bite Away®

| N | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ||

| Swelling | 108 | 74 |

| Pain | 85 | 58.2 |

| Pruritus | 52 | 35.6 |

| Dyspnea | 2 | 1.4 |

| Duration of administration | ||

| 3 seconds | 62 | 42.5 |

| 6 seconds | 75 | 51.4 |

| Number of administrations | ||

| Once | 66 | 45.2 |

| Twice | 36 | 24.7 |

| Three times | 13 | 8.9 |

| Four times | 6 | 4.1 |

| Five times | 5 | 3.4 |

| NA | 20 | 13.7 |

| Time of administration after insect bite | ||

| Within 5 minutes | 73 | 50 |

| Within 15 minutes | 106 | 72.6 |

| More than 1 hour | 19 | 13 |

| NA | 15 | 10.3 |

Abbreviation: NA, data not available.

Figure 2.

Box-plot of VAS values (on a scale of 10 = maximum severity) of swelling (A), pain (B) and pruritus (C). Results are given for development of symptoms after 2, 5, and 10 minutes after administration of Bite Away® compared with situation before treatment.

Note: Significantly different P values of Wilcoxon test for comparison between time-points are presented.

Abbreviation: VAS, visual analog scale.

Figure 3.

Reduction of swelling (A) and pain (B) is presented as VAS (on a scale of 10 = maximum severity) for each time-point of measurement stratified by age of patients.

Note: Wilcoxon tests show no statistical differences between subgroups (P > 0.05) for 0, 2, 5, and 10 minutes.

Abbreviation: VAS, visual analog scale.

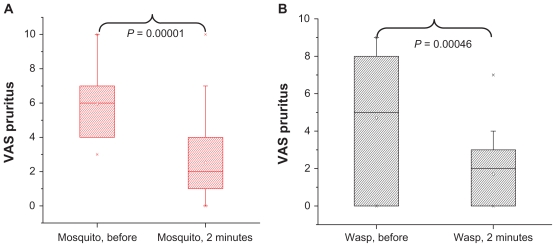

Similarly, a statistical significant decrease of the VAS pruritus score was visible from 5 before treatment, to 2 after 2 minutes, and 0 after 5 and 10 minutes (Figure 2C). The decrease of VAS pruritus of the two subgroups’ patients with wasps or mosquito bites is comparable. Immediately after administration of Bite Away®, there was a significant decrease of pruritus whether the patient was stung/bitten by a wasp or a mosquito (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The reduction of VAS pruritus (on a scale of 10 = maximum severity) is presented as box-plot stratified for insect type. A highly significant reduction of pruritus is visible for mosquitos (A) and wasps (B) before treatment, to 2 minutes after treatment with Bite Away®.

Note: P values of the Wilcoxon test for comparison between time-points are presented, (wasp N = 20; mosquito N = 32).

Discussion

In this realistic field study, we found a rapid effect after Bite Away® administration on VAS score for swelling, pain, and pruritus after insect bites/stings. Locally administered, concentrated heat, which was recognized by the patients as a very short and targeted induction of almost painful high temperature on the skin, led to a fast improvement of symptoms. The symptoms usually faded away after 10 minutes. Pain reduction, especially for patients with wasp stings, was the dominant effect. In the context of a non-interventional trial in 2009, an alternative topical treatment with hydrocortisone also showed a reduction of pain, itch, erythema, and swelling after insect stings, but the symptom scores decreased slowly over a period of 7 days.12 In an experimental setting, 12 atopic dermatitis patients received a focal histamine stimulus (20 mC) given by iontophoresis, which was treated with anesthetics ( lidocaine, prilocaine, xylocaine) and antihistamines (dimetindene maleate). None of the antihistaminic and anesthetic agents reduced the pruritus intensity significantly, when applied for 15 minutes.13 In contrast, a placebo-controlled, cross-over study in 27 mosquito- bite-sensitive subjects showed that prophylactically given cetirizine 10 mg and ebastine 10 mg daily had a significant effect on wheals and pruritus caused by Aedes aegypti laboratory mosquitoes.14 When cetirizine 10 mg was given prophylactically alone, only VAS scores of pruritus differed significantly from the placebo group after 15 and 60 minutes but not after 12 and 24 hours, in a field study in southern Finland, with Aedis communis mosquitos.15 An explanation of the mechanism of action for the effectiveness of concentrated heat in this study can be found in the activation and suppression of receptors. A rapid temperature increase to a maximum of 51°C leads to an activation of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) via C- and Aδ-fibers.16 Midge saliva leads to an activation effect comparable to the stimulation of the proteinase-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2).17 PAR-2 are localized on human skin mast cells. PAR2 activation leads to an increase of Ca2+ ions from intracellular calcium stores and subsequent histamine release.18 Through the activation of TRPV1 by concentrated heat, PAR-2 carrying C-fibers may be influenced, suppressing pruritus. Further clinical studies showed that itch intensity ratings were significantly reduced during repeated noxious heat.19,20

Neither the concentrated heat during treatment, nor the number of administrations showed any influence on pain perception after 2, 5, and 10 minutes. This could be seen even in the stratum of children less than 6 years, who show a much more pronounced cutaneous pain perception. Interestingly, only a few patients needed additional medical treatment. Due to the study design, it could not be established for sure whether the two female patients suffering from dyspnea had an anaphylactic reaction. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of Bite Away® in treating severe insect sting anaphylaxis is known to the authors from the emergency medical services. Controlled studies of the efficacy of the treatment of severe insect sting anaphylaxis and the mode of action of Bite Away® are still necessary.

Conclusions

Bite Away® reduced VAS scores significantly for swelling, pruritus, and pain when used after insect bites/stings in this open cohort-study. Compared with alternatives of pruritus and pain treatment after insect bites/stings, Bite Away® seems to be the fastest treatment option already available.

Acknowledgments

This study was completely sponsored by RIEMSER Arzneimittel AG. We gratefully thank Anja Berensmeier and Gerd Franke for statistical evaluation.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions

CM and LF were responsible for conception and general supervision of the research group. CM, BG, and LF made substantial contributions to data collection and study design. AB, GF, CM, BG, and LF contributed to analysis and interpretation of data; CM, BG, and LF were involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Christian Müller and Beatrice Großjohann are employees of RIEMSER Arzneimittel AG. Lutz Fischer declares that he has no competing interests.

References

- 1.Charpin D, Birnbaum J, Vervloet D. Epidemiology of hymenoptera allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 1994;24(11):1010–1015. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1994.tb02736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barsky HE. Stinging insect allergy. Avoidance, identification, and treatment. Postgrad Med. 1987;82(3):157–158. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1987.11699959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simone DA, Ngeow JY, Whitehouse J, Becerra-Cabal L, Putterman GJ, LaMotte RH. The magnitude and duration of itch produced by intracutaneous injections of histamine. Somatosens Res. 1987;5(2):81–92. doi: 10.3109/07367228709144620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomsen JS, Sonne M, Benfeldt E, Jensen SB, Serup J, Menne T. Experimental itch in sodium lauryl sulphate-inflamed and normal skin in humans: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of histamine and other inducers of itch. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146(5):792–800. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golden DB, Marsh DG, Kagey-Sobotka A, et al. Epidemiology of insect venom sensitivity. JAMA. 1989;262(2):240–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Settipane GA, Boyd GK. Prevalence of bee sting allergy in 4,992 boy scouts. Acta Allergol. 1970;25(4):286–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1970.tb01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golden DB. Insect sting anaphylaxis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007;27(2):261–272. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark S, Camargo CA., Jr Emergency treatment and prevention of insect-sting anaphylaxis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;6(4):279–283. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000235902.02924.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnard JH. Studies of 400 Hymenoptera sting deaths in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1973;52(5):259–264. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(73)90044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tracy JM. Insect allergy. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011;78(5):773–783. doi: 10.1002/msj.20286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer J, Knaudt B, Caroli UM, Biedermann T. Factory packed and expired – about emergency insect sting kits. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6(9):729–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schalla W. Results of a prospective cohort-study. Pharmazeutische Zeitung. 2009;154(40):3774–3777. German. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weisshaar E, Forster C, Dotzer M, Heyer G. Experimentally induced pruritus and cutaneous reactions with topical antihistamine and local analgesics in atopic eczema. Skin Pharmacol. 1997;10(4):183–190. doi: 10.1159/000211503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karppinen A, Kautiainen H, Petman L, Burri P, Reunala T. Comparison of cetirizine, ebastine and loratadine in the treatment of immediate mosquito-bite allergy. Allergy. 2002;57(6):534–537. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.13201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reunala T, Lappalainen P, Brummer-Korvenkontio H, Coulie P, Palosuo T. Cutaneous reactivity to mosquito bites: effect of cetirizine and development of anti-mosquito antibodies. Clin Exp Allergy. 1991;21(5):617–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1991.tb00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tominaga M. The role of TRP channels in thermosensation. In: Liedtke W, Heller S, editors. TRP Ion Channel Function in Sensory Transduction and Cellular Signaling Cascades. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinhoff M, Neisius U, Ikoma A, et al. Proteinase-activated receptor-2 mediates itch: a novel pathway for pruritus in human skin. J Neurosci. 2003;23(15):6176–6180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06176.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moormann C, Artuc M, Pohl E, et al. Functional characterization and expression analysis of the proteinase-activated receptor-2 in human cutaneous mast cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126(4):746–755. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yosipovitch G, Duque MI, Fast K, Dawn AG, Coghill RC. Scratching and noxious heat stimuli inhibit itch in humans: a psychophysical study. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Apr;156(4):629–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yosipovitch G, Fast K, Bernhard JD. Noxious heat and scratching decrease histamine-induced itch and skin blood flow. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(6):1268–1272. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]