Abstract

Background

There is a lack of comparable data on physical activity, sedentary behavior, and dietary habits among Arab adolescents, which limits our understanding and interpretation of the relationship between obesity and lifestyle parameters. Therefore, we initiated the Arab Teens Lifestyle Study (ATLS). The ATLS is a multicenter collaborative project for assessing lifestyle habits of Arab adolescents. The objectives of the ATLS project were to investigate the prevalence rates for overweight and obesity, physical activity, sedentary activity and dietary habits among Arab adolescents, and to examine the interrelationships between these lifestyle variables. This paper reports on the objectives, design, methodology, and implications of the ATLS.

Design/Methods

The ATLS is a school-based cross-sectional study involving 9182 randomly selected secondary-school students (14–19 years) from major Arab cities, using a multistage stratified sampling technique. The participating Arab cities included Riyadh, Jeddah, and Al-Khobar (Saudi Arabia), Bahrain, Dubai (United Arab Emirates), Kuwait, Amman (Jordan), Mosel (Iraq), Muscat (Oman), Tunisia (Tunisia) and Kenitra (Morocco). Measured variables included anthropometric measurements, physical activity, sedentary behavior, sleep duration, and dietary habits.

Discussion

The ATLS project will provide a unique opportunity to collect and analyze important lifestyle information from Arab adolescents using standardized procedures. This is the first time a collaborative Arab project will simultaneously assess broad lifestyle variables in a large sample of adolescents from numerous urbanized Arab regions. This joint research project will supply us with comprehensive and recent data on physical activity/inactivity and eating habits of Arab adolescents relative to obesity. Such invaluable lifestyle-related data are crucial for developing public health policies and regional strategies for health promotion and disease prevention.

Keywords: lifestyle, obesity, physical activity, sedentary behavior, dietary habits

Background

In developing countries, there has been a recent increase in emerging diet and lifestyle-related noncommunicable diseases (NCDs).1 Further, a World Health Organization (WHO) report indicates that the global burden of noncommunicable diseases in the developing countries is projected to substantially increase over the next decade.2 This shift in the pattern of NCDs in developing countries is mostly due to rapid nutrition transition, increasing urbanization, reduced occupational-work demands, and increased sedentary lifestyle.3 Thus, monitoring diet and lifestyle-related habits is considered important from a public health perspective.

Over the past 4 decades, tremendous changes have taken place in the lifestyle of youth living in almost all major Arab cities. Calorie-dense foods and sugar-sweetened beverages are increasingly becoming accessible to Arab children and adolescents, while the time spent in sedentary activity, such as TV viewing and computer and internet use, has sharply increased.4,5 This dramatic lifestyle transformation is thought to have contributed immensely to the epidemic of overweight and obesity among Arab children and adolescents that has been recently observed.6,7 Estimates of overweight or obesity in the Arabian Gulf States are as high as 42.2% in Kuwaiti adolescent males and 42.4% in Bahraini adolescent females.7 In Saudi Arabia, where serial cross-sectional analyses of body mass index (BMI) (or fat %) in children and adolescents were carried out over time, there has been a clearly rising trend in obesity over the past 2 decades.8,9

It is well recognized that childhood obesity is associated with comorbidities.10,11 Metabolic complications associated with obesity during childhood increase the risk for type 2 diabetes and early cardiovascular disease.12 Furthermore, obesity in adolescence has been shown to be significantly correlated with an increased risk of severe obesity in adulthood.13 Although genetic factors may predispose an individual to gain weight, the biggest effect on energy balance in children and adolescents is lifestyle behavior, such as physical activity, sedentary activity, and dietary habits. Indeed, previous research has shown that lifestyle-related behaviors that are associated with obesity among school children include TV viewing, computer and Internet use, physical activity inside and outside schools, and consumption of breakfast and sugary drinks.14,15 In addition, sleeping duration in adolescents has been linked to an increased chance of being obese.16

Presently, there is a real concern regarding the increase in unhealthy dietary habits including greater consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks by young people and the possible role of these beverages in the pathogenesis of childhood obesity.17 A clustering of unhealthy dietary habits that soft drinks may bring about is also a concern. A recent study on Saudi Arabian children aged 10–19 years has reported a significantly positive correlation between sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and poor dietary habits.18 Moreover, among healthy dietary habits is the daily consumption of a healthy breakfast. Research studies have indicated that breakfast-skipping is highly prevalent in different parts of the world,19,20 as well as in many Arab countries.21,22 There is a possible role for breakfast consumption in maintaining normal weight status in children and adolescents. For example, findings from a study conducted on adolescents from the United States indicated that breakfast consumption during school days was associated with approximately 30% lower risk of being overweight or obese.23 In contrast to these previous findings, a high risk of obesity was associated with eating breakfast at school in Bahraini boys and girls aged 12–17 years.22

Participation in health-enhancing physical activity is a key determinant of energy expenditure in youth and it leads to improved cardiovascular and metabolic fitness as well as bone health.24–26 Persistent physical inactivity, on the other hand, is detrimental to health and well-being,27 and has been shown to be associated with a less healthy lifestyle.28 In addition, recent research findings have shown that TV viewing (sedentary activity) and physical activity appear to be separate entities and are independently associated with metabolic risk.29 In the majority of the Arab countries, however, there is a paucity of reliable physical activity data related to children and adolescents, and national physical activity surveillance is surprisingly lacking. Even for the small number of studies reporting physical activity data,30–33 it is difficult to make any comparison between findings from these studies because of varying methodology and differences in the physical activity instruments. Nevertheless, available research on some Arab countries using objective monitoring of daily physical activity levels has indicated that a high proportion of Saudi Arabian school children were not active enough to meet the minimal weekly requirement of moderate to vigorous health-enhancing physical activity.34 In an international comparison study, some Arab school children had the lowest prevalence of walking or riding a bicycle to school.35 This low physical activity level of Arab children, along with the high prevalence of pediatric obesity, led to the release of the Arab strategy for combating obesity and promoting physical activity, which urges governmental and nongovernmental organizations to adopt policies and action plans, as well as implement sets of programs aimed to prevent obesity and encourage active living among all age groups in the Arab countries.36

To the best of our knowledge, no studies throughout the Arab countries have used standardized assessment methods to systematically investigate the lifestyle habits of adolescents relative to the levels of overweight and obesity. Simultaneous monitoring of such lifestyle habits, including physical activity, sedentary activity and eating behavior of Arab adolescents, using standardized data-collection procedures, and studying the interactions between them are essential tools in the implementation of national strategies for the promotion of healthy lifestyle and preventing body weight gain and related comorbidities. The information obtained from such data is likely to lead to subsequent interventional studies. The Arab Teens Lifestyle Study (ATLS) project was a recent initiative to assess the lifestyle habits, including physical activity patterns, sedentary activity and eating habits of randomly selected samples of secondary-school boys and girls (14–19 years) living in major Arab cities.37 Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to provide an elaborate overview of the objectives, design, methodology, and implementations of the ATLS, which is a unique pan-Arab collaborative research project.

Objectives of the ATLS

The main aim of the ATLS project is to collect reliable and comparable lifestyle data from randomly selected adolescents (aged 14–19 years) living in major Arab cities. More specific objectives of ATLS project are: (1) to provide updated prevalence rates for overweight and obesity, physical activity, sedentary activity, and dietary habits among Arab adolescents; and (2) to examine the interrelationships between obesity, physical inactivity, and unhealthy lifestyle habits among Arab adolescents. The ATLS project also intends to provide baseline lifestyle data for which time trends analysis can be carried out on future lifestyle surveillances. Two a priori hypotheses were stated. The first hypothesis is that overweight/obesity, sedentary activity, and unhealthy dietary habits are highly prevalent among Arab adolescents, especially among adolescents from the Arabian Gulf countries. The second hypothesis is that physical activity levels are lower in females compared with those in males, irrespective of city or region.

Design and methods

Design

ATLS is a school-based cross-sectional multicenter collaborative study. Future serial data collections are possible.

Selection of the participating cities in the ATLS project

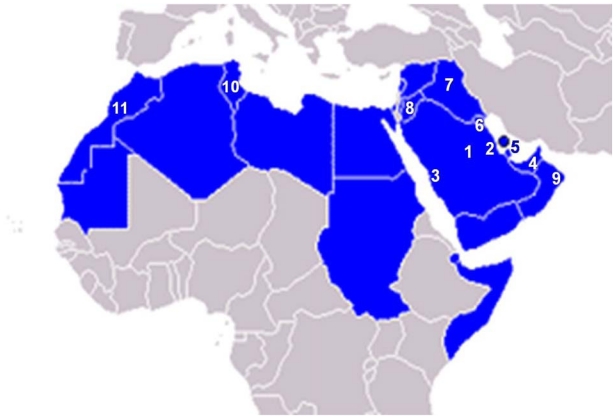

The ATLS project aimed to study the lifestyle habits of Arab adolescents living in selected Arab urban areas. Generally, the Arab urban cities are the most affected by recent lifestyle changes occurring among youth. Therefore, it was decided that for logistic reasons it may not be practical to randomly select the participating cities (centers); therefore, we invited all interested researchers from different Arab cities to participate in the ATLS project. This was done through personal communications using the Arab Center for Nutrition as a platform for this contact. Our criteria for the selection of the cities were: (1) they must be an urbanized area with a sufficiently large population size (>100,000 people) to insure diversity; (2) the city must have a well-defined population within a country; and (3) if there was more than one city within a country that wished to participate in data collection as part of the ATLS project, they must not be within a proximate geographical location. Figure 1 shows the participating cities within a map of the greater Arab countries.

Figure 1.

Map of the Arab countries showing the participating cities in the ATLS project.

Notes: 1, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 2, Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia; 3, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia; 4, Dubai, UAE; 5, Bahrain; 6, Kuwait; 7, Mosel, Iraq; 8, Amman, Jordan; 9, Muscat, Oman; 10, Tunisia, Tunisia; 11, Kenitra, Morocco.

Abbreviation: ATLS, Arab Teens Lifestyle Study.

Study sample

The target population of the ATLS project consists of adolescent males and females in secondary schools who were free of any physical deformity. In general, the majority of the adolescent population is enrolled in secondary schools. The minimum required sample size in each city was determined so that the sample proportion would be within ±0.05 of the population proportion with a 95% confidence level. For example, in the city of Riyadh, where the population of male students in public and private secondary schools is approximately 75,000, the required total sample size for male students is 382. Depending on the participating center, 10%–15% additional students were included to account for missing data.

A multistage stratified random sampling technique was used to select the sample. At the first stage, a systematic random sampling procedure was used to select the schools. The schools were stratified into boys’ and girls’ secondary schools, with further stratification into public and private schools. The selection of the private/public schools was proportional to size. Different strategies were used to select schools from within each participating city. For most of the participating cities, four schools (two each from boys’ and girls’ schools) were selected from each of the four geographical areas (east, north, south, and west). In some cities, however, schools were distributed within the city based on administrative set-up. In this case, the selection of schools was based on good representation of the city districts. At the second stage, classes were selected at each grade (level) using a simple random sampling design. In this way, one class was randomly selected in each grade of the three grades (grades 10, 11, and 12) in each secondary school. Therefore, we have a total selection of at least 24 classes (12 each from boys’ and girls’ schools) in each city. All students in the selected classes, who were free from any physical deformity, were invited to participate in the study. Assuming an average size of 30 students per class, it was expected that the total sample size from each city would be approximately 720 boys and girls. Because of the differences in class size from city to city and from private to public schools, the sample sizes for the participating cities are varied. In addition, some cities have more dispersed schools, which required the selection of more schools for a better representation.

The total sample of the ATLS project was collected in two phases. The first batch of data collection was conducted during the fall of 2009 (during October/November, 2009). They included samples from the following participating Arab cities (Figure 1): Riyadh, Jeddah, and Al-Khobar (Saudi Arabia), Bahrain, Dubai (United Arab Emirates), Kuwait, Amman (Jordan), and Mosel (northern Iraq). The second set of data collection occurred during the spring and fall of 2010. They included samples from the following Arab cities: Muscat (Oman), Tunisia (Tunisia), and Kenitra (Morocco). The study protocol was approved by the Research Center at King Saud University, as well as by the General Directorate of School Education and school principals in each respective city. In addition, each participating center was responsible for securing schools’ and students’ approval for conducting the ATLS survey. Table 1 shows the sample size for the participating cities, with a total number of 9182 Arab adolescents. The number of females in the sample slightly exceeded that of male participants (52% versus 48%).

Table 1.

Participating Arab cities and the sample size in the ATLS project

| Participating city (country) | Sample size | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | |

| Riyadh (Saudi Arabia) | 493 | 508 | 1001 |

| Al-Khobar (Saudi Arabia) | 348 | 367 | 715 |

| Jeddah (Saudi Arabia) | 563 | 632 | 1195 |

| Dubai (United Arab Emirates) | 420 | 503 | 923 |

| Kuwait (State of Kuwait) | 465 | 448 | 913 |

| Amman (Jordan) | 386 | 349 | 735 |

| Mosel (Iraq) | 350 | 373 | 723 |

| Bahrain | 375 | 341 | 716 |

| Muscat (Oman) | 376 | 442 | 818 |

| Tunisia (Tunisia) | 352 | 489 | 841 |

| Kenitra (Morocco) | 278 | 324 | 602 |

| Grand total | 4406 | 4776 | 9182 |

Abbreviation: ATLS, Arab Teens Lifestyle Study.

ATLS research instruments and procedures

The ATLS research instruments that were used for the collection of lifestyle information consisted of 47 items, including the first five items that the researcher must measure/record. These items included age, weight, height, waist circumference (WC), and student’s level of study. Items six to 34 contained the physical activity questionnaire. Items 35 to 37 were questions on sedentary activity. Lastly, items 38 to 47 were specific questions on dietary habits. To ensure that the survey was manageable time-wise and to increase its reliability, we had to omit a large number of demographic, socioeconomic and environmental variables that were considered at the planning stage. The questionnaire took a mean time of approximately 25 minutes to complete by the student.

To ensure accurate and consistent measurements throughout this multicenter project, a standardized measurement protocol was employed in all participating data collection centers. The operational manual included sufficient instructions on sampling procedures, weight, height, and WC measurements, how to conduct the questionnaire properly, and answers to some common questions that the field researchers might encounter during the actual data collection period. Each participating center was fully responsible for training its research team. We also provided each center with a set of written instructions and some training tips. We even urged and encouraged each center to conduct a pilot study prior to the actual data collection. The pilot work served to check every step of the data collection procedures and to minimize problems that might be encountered during the actual data collection phase. In addition, the participating centers were asked to avoid any data collection on months of hot, humid or very cold weather, since these environmental conditions may have a negative effect on the pattern of physical activity. Days right after extended holidays or days where there were midterm examinations were also avoided for the same reason.

Anthropometric measurements

Anthropometric variables included body weight, height, and WC. Measurements were performed in the morning by a trained researcher according to written standardized procedures. Body weight was measured without shoes and with minimal clothing to the nearest 100 g using a calibrated portable scale (either Seca 770, Seca 872, Seca 880, Seca 882 or a similar model; Seca, Hamburg, Germany). Height was measured to the nearest cm while the subject was in the full standing position (in the Frankfort horizontal plane) without shoes using a calibrated portable stadiometer. BMI was calculated as a ratio of weight in kg by height squared in meters. The International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) age- and sex-specific BMI cut-off reference standards38 were used to identify overweight and obesity in adolescents aged between 14–17 years. For participants aged 18 years and older, we used WHO adults’ cut-off points.39 WC was recently reported to be the best simple measure of fat distribution in children aged 7–17 years, since it is least affected by sex, race, and overall adiposity.40 WC was measured horizontally to the nearest 0.1 cm using a nonstretchable measuring tape at the level of the umbilicus and at the end of gentle expiration. When measuring WC, the tape was snug, but did not compress the skin. In some centers, for cultural reasons, WC was measured in girls with a light shirt on, and this was later adjusted (corrected) using a correction factor of −1 cm, based on the results of a small pilot study that we conducted previously.

Physical activity assessment

Physical activity is defined as bodily movement produced by the skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure above the resting value.25 It is a multidimensional behavior and because of its complexity, physical activity is difficult to accurately assess under free-living conditions. However, physical activity intensity, duration, and frequency can be measured using either subjective or objective methods.41 Because of the nature and diversity of the ATLS project, a self-reported questionnaire was used as a means to assess the level of physical activity of the young Arab participants. The ATLS physical activity questionnaire (available for download at http://faculty.ksu.edu.sa/hazzaa/DocLib31/ATLS%20Questionnaire.pdf) is a modified questionnaire based on a previously developed physical activity questionnaire for youth. The original questionnaire was previously shown to have a high reliability (intraclass correlation [ICC] = 0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.70–0.93) and an acceptable validity (r = 0.30; P < 0.05) against a pedometer in adolescent males and young adults aged 15–25 years.42,43 However, the previous validation study was conducted on a convenient sample of males only and with a wide age range (15–25 years). Therefore, another validity study,44 using a random sample of both females and males aged 14–19 years, was conducted to validate the ATLS physical activity questionnaire against an electronic pedometer, and was shown to have an acceptable validity coefficient (r = 0.37; P < 0.001).

The participants completed the questionnaire using the Arabic version while in their classrooms under the supervision of their teachers and in front of at least one of the research assistants. The questionnaire was designed to collect complete information on frequency, duration, and intensity of a variety of light-, moderate-, and vigorous-intensity physical activities during a typical (usual) week. The physical activity questionnaire covers such domains as transport, the household, fitness and sports activities. Moderate-intensity physical activity includes activities such as normal pace walking, brisk walking, recreational swimming, household activities, and moderate-intensity recreational sports such as volleyball, badminton, and table tennis. Moderate-intensity physical activities were assigned metabolic equivalent (MET) values based on the compendium of physical activity45 and the compendium of physical activity for youth.46 Household activities were given a mean MET value of 3. This is because they include some items that may require less than 3 METs such as washing dishes (2.5 METs), cleaning the bathroom (2.5 METs), cooking (2.5 METs), and ironing (2.3 METS), as well as other household activities that require 3 METs or more such as car washing (3 METs), vacuuming (3.5 METs), mopping (3.5 METs), and gardening (3.5 METs). Moderate-intensity recreational sports were assigned an average MET value equivalent to 4 METs. Vigorous-intensity physical activity and sports included activities such as stair-climbing, jogging, running, cycling, self-defense, weight-training and vigorous-intensity sports such as soccer, basketball, handball, and single tennis. Vigorous-intensity sports were assigned an average MET value equivalent to 8 METs. Slow walking, normal-pace walking, and brisk walking were assigned MET values of 2.8, 3.5, and 4.5 METs, respectively, based on modified METs values from the compendium of physical activity for youth.46 Furthermore, the physical activity questionnaire contains some additional questions on reasons for being active or inactive such as “Where and when do you usually exercise?” and “With whom do you usually exercise?”

Measurement of physical activity levels

Two measures of physical activity levels are used in the ATLS. The first measure of physical activity levels is the total number of minutes spent in physical activity per week as well as the number of minutes spent in moderate- and vigorous-intensity physical activity per week. The minimal activity level based on time spent on physical activity per week was calculated according to the minimal recommended physical activity for children and youth, which is 1 hour of at least moderate-intensity activity per day.47 This is an equivalent of 420 minutes per week (60 minutes multiplied by 7 days per week). The second measure of physical activity that is used in the ATLS considers both time and intensity of physical activity. This includes the total METs minutes per week as well as the METs minutes per week resulting from each moderate- and vigorous-intensity physical activity. This is an equivalent of the sum of time spent in specific activity per week multiplied by the MET value of that activity. Participants were divided into physically active or inactive based on total physical activity cut-off scores of 1680 METs minutes per week (60 minutes per day × 7 days per week × 4 METs), corresponding to 1 hour of daily moderate-intensity physical activity.

Sedentary activity and sleeping hours

The section on sedentary activity and sleeping hours follows the physical activity questions, and aims to determine important information from adolescents related to the daily time spent on TV viewing, video games, and computer and Internet use, as well as the number of sleeping hours per day (night and day). Recent research in a pediatric population suggests a relationship between short sleep duration and obesity.48 The possible mechanism for this relationship involves both metabolic and behavioral factors. For a maximal cut-off value for total screen time, we used 2 hours per day, recommended by the American Academy of Pediatric guidelines.49

Dietary habits questionnaire

In addition to the physical activity questionnaire, in a separate section, the ATLS questionnaire included ten specific questions designed to collect the frequency of certain dietary habits of adolescents. They included questions related to how many times per week does the participant consume breakfast, sugar-sweetened drinks including soft beverages, vegetables (cooked and uncooked), fruits, milk and dairy products, donuts/cake, sweets and chocolates, energy drinks, and fast foods. The fast foods in this regard include some examples from both Western fast foods as well as some Arabic fast food choices such as shawarma (grilled meat or chicken in pita bread with some salad). These questions cover some healthy and unhealthy dietary habits. The student has a choice of answers ranging from zero intake (nothing) to a maximum intake of 7 days per week (every day).

Data handling, data entry, and cleaning procedures

Data at each center were entered into a computer using standardized entry codes written on an SPSS data file (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). The entered data were then sent to one central processing location (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia). The original data collection sheets were kept intact inside large envelopes in each center. A few participating centers did not enter their data, and they sent copies of their data directly to the data management center instead where they were entered into a computer. At the central processing center, all data were checked again for outliers and incorrect entries. Syntax statements were written to compute activity energy expenditure, as well as overweight and obesity cut-off scores relative to age and sex.

Furthermore, to avoid overreporting, physical activity scores were cleaned and truncated at reasonable and realistic levels, taking into account the fairly long time spent in learning at schools, doing homework, sleeping, and TV time. Reported times for each vigorous-intensity physical activity such as jogging/running, weight-training, basketball, handball, and soccer were truncated at 120 minutes per day, while the time spent on household activity was truncated at 180 minutes per day. In addition, the maximum number of stair levels taken by students per day was capped to 30 floors; this means 10 floors three times a day. We observed that there were a high number of stair levels answered by participants in the Dubai sample (possibly because of the presence of many high-rise buildings). When assigning a MET value for stair use, we assumed that it takes approximately 20 seconds for an ordinary adolescent to complete a full flight of stairs with 28–30 steps. The maximum total time spent on physical activity per week was truncated at 1680 minutes (28 hours), or 4 hours of physical activity per day. The combined time of TV viewing, computer use, and Internet time was also truncated at 16 hours per day.

Discussion

The ATLS project has provided us with a unique opportunity to collect and analyze important lifestyle information from Arab adolescents using standardized data collection procedures. This is the first collaborative Arab project that has attempted to assess broad lifestyle-related variables in a large sample of adolescents from numerous urbanized regions of Arab countries. It is expected that the findings stemming from this regional research project will be substantial and very beneficial from a public health perspective. The results of this joint research will provide comprehensive and recent data on physical activity/inactivity patterns, sedentary behavior and eating habits of Arab adolescents, and their relationships with obesity measures, thus enabling us to cross-regionally compare the prevalence rates of several lifestyle-related parameters. Worldwide, childhood obesity is a significant public health issue,11 and the prevalence of pediatric obesity has considerably increased across developed and developing countries.50 A lack of comparable data on physical activity and sedentary behavior among Arab adolescents limits our understanding and interpretation of the complex relationship between obesity and lifestyle parameters. Furthermore, this pan-Arab project will provide invaluable lifestyle-related baseline data that are crucial for developing public health policies and national as well as regional strategies for health promotion and disease prevention in this region of the world.

According to the Arab Human Development Reports,51 the population of Arab countries has nearly tripled since 1970, reaching 359 million in 2010. There is a profound demographic transformation taking place in the Arab region. This region has been characterized by large movements from rural to urban areas. This rapid urbanization is coupled with an increased growth of large cities. Furthermore, this region is also characterized by large numbers of youth. In fact, the majority of the Arab population (54%) is under the age of 25 years.51 Therefore, it is expected that this rapid urbanization, crowded population, propagated satellite TV, increased reliance on computer and telecommunication technology and decreased occupational-work demands, could lead to an inactive lifestyle pattern among the Arab population.

The ATLS project targets lifestyle habits of adolescents at the secondary school level, which typically spans an age range between 14–19 years. These formative years of adolescence represent a crucial stage in the human life cycle, as it is the stage where lifestyle habits are formed and well established. During this period, adolescents become more independent and have increased access to food choices apart from those available at home. It is also during this period that the adolescent increases his/her social interaction with peers of similar age and develops individual eating habits and physical activity patterns. Research has also shown that dietary habits are established in the mid-teens and they are closely associated with lifestyle.52 A better understanding of the relationships of healthy behavior among youth is necessary for effective prevention and management of lifestyle-related risk factors.

Some of the pressing questions that might be answered by ATLS findings include the following: “What are the prevalence rates of overweight/obesity, physical activity and sedentary behavior among Arab adolescents, and are these rates different relative to sex, age and regional variations?” “What are the prevailing healthy and unhealthy dietary habits among Arab adolescents and are they affected by variables such as age, sex and region?” “How much agreement between levels of BMI and WC in male and female Arab adolescents?” “Do obese adolescents have a low level of physical activity, high level of sedentary activity or unhealthy dietary habits?” “Does having daily breakfast or lower sugar-sweetened beverages reduce the risk of being obese among Arab adolescents?” “Is there a negative relationship between the level of physical activity and sedentary behavior?” “What is the proportion of Arab adolescents having a sufficient daily sleep duration?” “Are adolescents who have a relatively short daily sleep duration at higher risk of being obese compared with those who get adequate sleep?” And finally, “Is there a clustering of health-related behaviors among Arab adolescents?” A clustering of unhealthy lifestyle habits such as unhealthy dietary practice, inactivity and sedentary behaviors may be of a major public health concern.

Undoubtedly, the major advantage of the ATLS project is the standardized data collection procedures and the simultaneous assessment of several lifestyle variables. Additionally, an important strength of the ATLS project is its diversity, since the participants are drawn from a number of participating centers (cities) from different Arab regions. Inclusion of WC in addition to BMI as a measure of obesity will further enhance our understanding of the behavioral correlates of central obesity in Arab adolescents, especially since it has been shown that WC is a better predictor of cardiovascular disease in children than BMI.53 Data from the Bogalusa Heart Study have also indicated that among overweight children, waist to height ratio is more strongly associated with adverse risk factors than the levels of BMI for age.54 A potential weakness of the ATLS project is the use of a self-reported questionnaire for collecting data on physical activity, sedentary behavior and dietary habits. However, because of the complexity and nature of this type of epidemiological research project, it was not practically possible to use more objective measures for such diverse behaviors. Despite this potential limitation, we strongly believe that the ATLS project is a unique research endeavor that has already proved that it is possible to perform such a collaborative multicenter lifestyle survey in Arab countries with fairly good coordination and considerable success.

The ATLS research group

Hazzaa M Al-Hazzaa, PhD, FACSM (King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia); Abdulrahman O Musaiger, PhD (Arab Center for Nutrition, Manamah, Bahrain); Nada A Abahussain, PhD (School’s Health Services, Ministry of Education, Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia); Reema F Tayyem, PhD (Hashemite University, Jordan); Hana I Al-Sobayel, PhD (King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia); Nouf A Alsulaiman, MSc (Jeddah, Saudi Arabia); Perevan A Al-Mofty, PhD (Koya University, Iraq); Ahmad R Al-Haifi, PhD (College of Health Sciences, Kuwait); Tamer E Desouki, MSc (Ministry of Education, Dubai, United Arab Emirates); Dina M Qahwaji, PhD (King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia); Hashem A Kilani, PhD (Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Oman); Gazi al-Marzooq, MSc (Ministry of Education, Bahrain); Jalila Elati, PhD (National Institute of Nutrition, Tunisia, Tunisia); Najat Mokhtar, PhD (Ibn Tofail University, Kenitra, Morocco).

Acknowledgments

Data collection of the ATLS in the city of Riyadh in Saudi Arabia was supported by a fund from the Educational Research Center, Deanship of Research, King Saud University. The authors also acknowledge the assistance of many research assistants who kindly participated in the data collection of the ATLS project throughout the participating Arab cities.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions

Hazzaa M Al-Hazzaa is the principal investigator of the ATLS project. He was responsible for the concept of the ATLS project, developed the lifestyle questionnaire, supervised data management and drafted this manuscript. Abdulrahman O Musaiger is the coprincipal investigator. He was involved in the conception of the ATLS project, took part in the modification of the questionnaire and contributed to the writing of this manuscript. All authors critically read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in this work.

References

- 1.Amuna P, Zotor FB. Epidemiological and nutrition transition in developing countries: impact on human health and development. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67:82–90. doi: 10.1017/S0029665108006058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Misra A, Khurana L. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11):S9–S30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aounallah-Skhiri H, Traissac P, El Ati J, et al. Nutrition transition among adolescents of a south-Mediterranean country: dietary patterns, association with socio-economic factors, overweight and blood pressure. A cross-sectional study in Tunisia. Nutr J. 2011;10:38. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-10-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehio Sibai A, Nasreddine L, Mokdad AH, Adra N, Tabet M, Hwalla N. Nutrition transition and cardiovascular disease risk factors in Middle East and North Africa countries: reviewing the evidence. Ann Nutr Metab. 2010;57(3–4):193–203. doi: 10.1159/000321527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Musaiger A. Overweight and obesity in Eastern Mediterranean Region: Prevalence, and causes. J Obes. 2011;2011:407237. doi: 10.1155/2011/407237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ng SW, Zaghloul S, Ali H, Harrison G, Popkin BM. The prevalence and trends of overweight, obesity and nutrition-related non-communicable diseases in the Arabian Gulf States. Obes Rev. 2011;12:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Hazzaa HM. Rising trends in BMI of Saudi adolescents: evidence from three national cross sectional studies. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2007;16:462–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Hazzaa HM. Prevalence and trends in obesity among school boys in Central Saudi Arabia between 1988 and 2005. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:1569–1574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Must A, Anderson SE. Effects of obesity on morbidity in children and adolescents. Nutr Clin Care. 2003;6:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reilly JJ, Methven E, McDowell ZC, et al. Health consequences of obesity. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:748–752. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.9.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nathan BM, Moran A. Metabolic complications of obesity in childhood and adolescence: more than just diabetes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2008;15:21–29. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3282f43d19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The NS, Suchindran C, North KE, Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P. Association of adolescent obesity with risk of severe obesity in adulthood. JAMA. 2010;304(18):2042–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiménez-Pavón D, Kelly J, Reilly JJ. Associations between objectively measured habitual physical activity and adiposity in children and adolescents: Systematic review. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5:3–18. doi: 10.3109/17477160903067601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreno LA, Rodríguez G. Dietary risk factors for development of childhood obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007;10:336–341. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3280a94f59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bawazeer NM, Al-Daghri NM, Valsamakis G, et al. Sleep duration and quality associated with obesity among Arab children. Obesity. 2009;17:2251–2253. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown CM, Dulloo AG, Montani JP. Sugary drinks in the pathogenesis of obesity and cardiovascular diseases. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(Suppl 6):S28–S34. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collison KS, Zaidi MZ, Subhani SN, Al-Rubeaan K, Shoukri M, Al-Mohanna FA. Sugar-sweetened carbonated beverage consumption correlates with BMI, waist circumference, and poor dietary choices in school children. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:234. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rampersaud GC, Pereira MA, Girard BL, Adams J, Metzl JD. Breakfast habits, nutritional status, body weight, and academic performance in children and adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:743–760. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vereecken C, Dupuy M, Rasmussen M, et al. HBSC Eating and Dieting Focus Group: Breakfast consumption and its socio-demographic and lifestyle correlates in schoolchildren in 41 countries participating in the HBSC study. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(Suppl 2):180–190. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-5409-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikki N, Abdul-Rahim HF, Shi Z, Holmboe-Ottesen G. Dietary habits of Palestinian adolescents and associated sociodemographic characteristics in Ramallah, Nablus and Hebron governorates. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:1419–1429. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010000662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.bin Zaal AA, Musaiger AO, D’Souza R. Dietary habits associated with obesity among adolescents in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Nutr Hosp. 2009;24:437–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boutelle K, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Resnick M. Weight control behaviors among obese, overweight, and nonoverweight adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27:531–540. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Centers for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janssen I, Leblanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:40. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health WHA5717. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aarnio M, Winter T, Kujala U, Kaprio J. Associations of health related behavior, social relationships, and health status with persistent physical activity and inactivity: a study of Finnish adolescent twins. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36:360–364. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.5.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ekelund U, Brage S, Froberg K, et al. TV viewing and physical activity are independently associated with metabolic risk in children: The European Youth Heart Study. PLoS Med. 2006;5(12):e488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Rukban MO. Obesity among Saudi male adolescents in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al Sabbah H, Vereecken C, Kolsteren P, Abdeen Z, Maes L. Food habits and physical activity patterns among Palestinian adolescents: findings from the national study of Palestinian schoolchildren (HBSC-WBG2004) Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:739–746. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007665501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henry CJ, Lightowler HJ, Al-Hourani HM. Physical activity and levels of inactivity in adolescent females ages 11–16 years in the United Arab Emirates. Am J Hum Biol. 2004;16:346–353. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taha AZ. Self-reported knowledge and pattern of physical activity among school students in Al Khobar, Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14(2):344–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Hazzaa HM. Physical activity, fitness and fatness among Saudi children and adolescents: implications for cardiovascular health. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:144–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guthold R, Cowan MJ, Autenrieth CS, Kann L, Riley LM. Physical activity and sedentary behavior among schoolchildren: a 34-country comparison. J Pediatr. 2010;157:43–49. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Musaiger AO, Al-Hazzaa HM, Al-Qahtani A, et al. Strategy to combat obesity and to promote physical activity in Arab countries. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2011;4:89–97. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S17322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Hazzaa HM, Musaiger A ATLS Group. Physical activity patterns and eating habits of adolescents living in major Arab cities: The Arab Teens Lifestyle Study. Saudi Med J. 2010;31:210–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cole T, Bellizzi M, Flegal K, Dietz W. Establishing a standard definition of child overweight and obesity worldwide: International survey. BMJ. 2000;320(7244):1240–1243. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.WHO. Report of WHO Consultation on Obesity. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2000. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daniel S, Khoury P, Morrison J. Utility of different measure of body fat distribution in children and adolescents. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:1179–1184. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.12.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kohl HW, Fulton IF, Caspersen CJ. Assessment of physical activity among children and adolescents. A review and synthesis. Prev Med. 2000;31:54–76. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al-Hazzaa HM, Al-Ahmadi M. A Self-reported questionnaire for the assessment of physical activity in youth 15–25 years: Development, reliability and construct validity. Arab Journal of Food & Nutrition. 2003;4(8):279–291. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Ahmadi M, Al-Hazzaa HM. Validity of a self-reported questionnaire for youth 15–25 years: Comparison with accelerometer, pedometer and heart rate telemetry. Saudi Sports Medicine Journal. 2004;7:2–14. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Hazzaa HM, Al-Sobayel HI, Musaiger AO. Convergent validity of the Arab Teens Lifestyle Study (ATLS) physical activity questionnaire. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:3810–3820. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8093810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, et al. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1575–1581. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ridley K, Ainsworth B, Olds T. Development of a compendium of energy expenditure for youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:45. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tremblay MS, Warburton DE, Janssen I, et al. New Canadian physical activity guidelines. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36:36–46. 47–58. doi: 10.1139/H11-009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marshall NS, Glozier N, Grunstein RR. Is sleep duration related to obesity? A critical review of the epidemiological evidence. Sleep Med Rev. 2008;12:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Public Education. American Academy of Pediatrics: Children, adolescents, and television. Pediatrics. 2001;107:423–426. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R. IASO International Obesity Task Force: Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obes Rev. 2004;(Suppl 1):4–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mirkin B. Arab Human Development Report. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programs; 2010. Population Levels, Trends and Policies in the Arab Region: Challenges and opportunities. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sweeting H, Anderson A, West P. Socio-demographic correlates of dietary habits in mid to late adolescence. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1994;48:736–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Savva SC, Tornaritis M, Savva ME, et al. Waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio are better predictors of cardiovascular disease risk factors in children than body mass index. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1453–1458. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Freedman DS, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Risk factors and adult body mass index among overweight children: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. 2009;123:750–757. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]