Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To determine patients' opinions regarding the person, method, and timing for disclosure of postoperative visual loss (POVL) associated with high-risk surgery.

PATIENTS AND METHODS: On the basis of findings of a pilot study involving 219 patients at Mayo Clinic in Florida, we hypothesized that at least 80% of patients would prefer disclosure of POVL by the surgeon, during a face-to-face discussion, before the day of scheduled surgery. To test the hypothesis, we sent a questionnaire to 437 patients who underwent prolonged prone spinal surgical procedures at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, or Mayo Clinic in Arizona from December 1, 2008, to December 31, 2009.

RESULTS: Among the 184 respondents, 158 patients gave responses supporting the hypothesis vs 26 with at least 1 response not supporting it, for an observed incidence of 86%. The 2-sided 95% confidence interval is 80% to 91%.

CONCLUSION: At least 80% of patients prefer full disclosure of the risk of POVL, by the surgeon, during a face-to-face discussion before the day of scheduled surgery. This finding supports development of a national patient-driven guideline for disclosing the risk of POVL before prone spinal surgery.

The risk of postoperative visual loss (POVL) varies with the nature and approach of the surgical procedure. From the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, cardiac and spinal fusion surgeries have the highest incidence of POVL.1 Patients undergoing spinal fusion surgery are more than 4 times likely to experience POVL than those undergoing abdominal surgery.1 Patients undergoing prone spinal fusion surgery are more than 2 times likely to experience POVL than those undergoing anterior spinal fusions.1 From the Postoperative Visual Loss Registry, patients at highest risk are those undergoing prolonged (>6 hours) procedures with substantial blood loss (>1000 mL).2 The American Society of Anesthesiologists' practice advisory for perioperative visual loss associated with spinal surgery suggests that a physician “consider” disclosing the risk of POVL to high-risk patients.3 The advisory does not address which physician(s) is (are) responsible for disclosure, nor does it address the timing of such disclosure.

The informed consent process is complex. It often involves the physician's judgment of what a reasonable patient would want to know regarding rare but catastrophic risks.4 Although physicians are not expected to list all possible risks and complications, they are expected to inform the patient of the most common risks and benefits, as well as those rare but devastating events that have the potential for significantly impacting patients' lifestyle. Some physicians weigh the risks based on the frequency of occurrence and do not discuss extremely rare risks and complications, despite the significant impact of such risks if they occur.

Thus far, there have been no practice guidelines by either the American College of Surgeons or the American Society of Anesthesiologists regarding the best method of discussing the potential for POVL with patients. Because the patient is cared for by at least two physicians (anesthesiologist and neurosurgeon) and no exact etiology for the visual loss has been determined, this remains a shared fear and responsibility of both physicians. As a result, which physician should be responsible for disclosure to the patient, and the setting and timing for this disclosure, remains a matter of much debate. Possible scenarios include a discussion of potential visual loss by the surgeon in an office setting preoperatively; discussion with the anesthesiologist in a preoperative clinic setting; or discussion by either party at the bedside in the preoperative holding area on the day of surgery. Unfortunately, the surgeon may make the clinical diagnosis and discuss surgical options with the patient all in the same clinic visit. At that point, the patient is beginning to contemplate surgical treatment as an option, and the disclosure of POVL may be a low priority for the surgeon. Likewise, anesthesiologists may be reluctant to discuss a rare but devastating complication with patients whom they meet only moments before proceeding to the operating room.

To date, no data have documented patients' opinions regarding this important issue. We surveyed patients who had undergone prolonged prone spinal surgery to aid in developing a national consensus for disclosure of risks of POVL associated with high-risk surgery.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

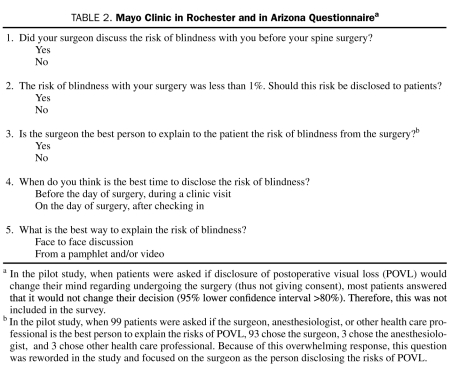

An exploratory qualitative study designed to develop a hypothesis was carried out at Mayo Clinic in Florida. A total of 219 patients who underwent prone spinal procedures (current procedural terminology [CPT] codes 22590-22632: prone spine cases with instrumentation) from January 1, 2009, to December 31, 2009, were invited to participate in a Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board–approved survey. All patients were sent a cover letter explaining POVL and a survey. Within 30 days, 99 responses were received (45.2% response rate). From the responders' answers, we developed the hypothesis that at least 80% of patients would prefer disclosure of the risk of POVL by the surgeon, during a face-to-face discussion, before the day of scheduled surgery.

To obtain a 90% statistical power of finding a significantly (α=.05) higher percentage than 80%, a sample size of 197 responses was needed. On the basis of a 45.2% response rate, 436 patients needed to be surveyed (436 = 197/0.452). On the basis of procedure logs from Mayo Clinic's campuses in Rochester and in Arizona, that number could be obtained from 13 months of data: December 1, 2008-December 31, 2009.

The survey was undertaken at Mayo Clinic's campuses in Rochester and Arizona. Patients were invited to participate if they had undergone prone spinal procedures (CPT codes 22590-22632; prone spine cases with instrumentation) during the 13 months. A cover letter explaining POVL and a 5-question survey were sent to 437 patients. Patients were enrolled if they completed and returned the survey within 30 days.

Two-sided confidence intervals were calculated by the Clopper-Pearson method.5 Because the survey was completed after surgery and responses may have been altered by changes in recall, analysis was repeated segmenting patients based on their recall of having been told the risk of blindness. In addition, association between responses and the number of days postoperatively when the survey was completed was evaluated by Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test (StatXact-9, Cytel Software Corp, Cambridge, MA). Association with age was tested similarly. Association of responses to center, sex, and age was tested by the Fisher exact test.

RESULTS

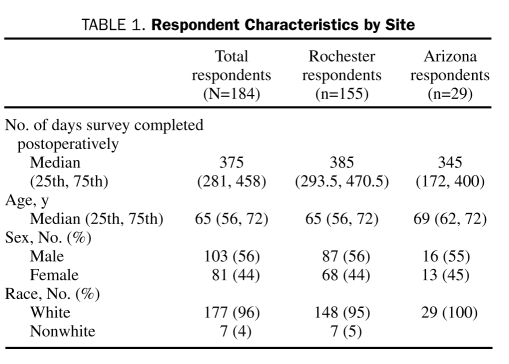

A total of 184 patients from Mayo Clinic's campuses in Rochester and in Arizona completed the questionnaire (42% response rate in the follow-up survey; Tables 1, 2). Among the 184 respondents, 158 (86%) answered “yes” to all 4 questions posed in the hypothesis (preferred the risk of POVL disclosed, by the surgeon, before the day of surgery in a face-to-face discussion), whereas 26 (14%) responded “no” to at least 1 of the survey questions. For this observed incidence of “yes” answers to all questions in the hypothesis (86%), the 2-sided 95% confidence interval is 80% to 91%.

TABLE 1.

Respondent Characteristics by Site

TABLE 2.

Mayo Clinic in Rochester and in Arizona Questionnairea

Additional tests were performed as sensitivity analyses. There was no association between responses and the number of days postoperatively when the survey was completed (P=.96), Mayo Clinic's site (Rochester or Arizona) (P=.26), patient age in years (P=.91), sex (P=.29), or race (P=.99).

Analysis was performed by segmenting responders into those who recalled being informed of the risk of POVL and those who recalled not being disclosed the risk. Of the 184 respondents, 14 (8%) could not recall if they had been told about POVL; 56 respondents (30%) recalled being told the risk of POVL by the surgeon before surgery. Among those 56 respondents, 55 (98%) answered “yes” to all components of the hypothesis. Of the 184 respondents, 114 (62%) recalled not having been disclosed the risk of POVL. Among this subset, 91 (80%) answered “yes” to all questions (P=.001). Still, among this subset of patients, most preferred to have been disclosed the risks of POVL, by the surgeon, in a face-to-face discussion before the day of surgery (P<.001; 95% lower confidence bound, 74%).

DISCUSSION

Our results show with reasonable certainty that at least 74% of patients undergoing prone spinal surgery prefer the disclosure of the risk of POVL, by the surgeon, in a face-to-face discussion before the day of surgery.

The importance of these findings can be interpreted in the context of US case law related to informed consent. From Salgo v Stanford6 in 1957, components of informed consent include the proposed medical intervention, its material risks and benefits, alternative treatments with associated risks, competency and capacity of the patient to make judgments, and a patient who is authorizing the medical intervention. All physicians have a legal (as well as a professional) responsibility to disclose the risks of surgery and anesthesia to the patient. All important information (material) in the patient's decision-making process should be included.7 If a reasonable patient wanted disclosure of this rare but devastating risk (“materiality”) and that patient would have withheld that consent should that risk have been disclosed (“causation”), then a physician may be held liable if POVL occurs.8 The results of the current study are novel in that they show materiality regarding disclosure of POVL (ie, three-fourths of patients who underwent high-risk prone spinal surgery desired full disclosure of the risk of POVL). However, the data do not show causation.

Even though the data establish materiality regarding disclosure of POVL, the risk of POVL is small. Retrospective studies have yielded heterogeneous incidence rates for POVL during spinal surgery that range from 0% to 0.2%.1,9,10 Current data are from cases of POVL that are reported to the visual loss registry (www.asaclosedclaims.org). Regardless of the low incidence of this complication, POVL is a devastating and life-altering morbidity. Thus, patients' wishes regarding POVL disclosure before prone spinal surgery provide much insight into the complex issue of informed consent.

One potential limitation of the current study is that it focused on the specific risk of POVL associated with prolonged prone spinal surgery. The results cannot be extrapolated to preferences of patients who undergo other procedures. For instance, we did not investigate other populations at high risk for POVL, such as patients undergoing cardiac surgery requiring cardiopulmonary bypass.11

Our study has several other limitations. Respondents may have differed in opinion from the other 58% of patients who did not respond to the survey. Because we did not contact survey nonresponders, comparisons cannot be made between nonresponders and responders. Responses may have differed if the survey had been taken preoperatively because no patient in our study experienced POVL. Finally, a striking demographic feature was that almost all respondents were white.

CONCLUSION

In an era in which a patient-centered model of care focuses on the patient's involvement in his or her own health care, it is appropriate that we include the patient's preference when examining the complicated issue of disclosure of POVL before high-risk procedures such as prone spinal surgery. We found that most patients want full disclosure of the rare risk of POVL, by the surgeon, in a face-to-face discussion before the day of surgery.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Dr Nottmeier is a consultant for Medtronic Navigation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shen Y, Drum M, Roth S. The prevalence of perioperative visual loss in the United States: a 10-year study from 1996 to 2005 of spinal, orthopedic, cardiac, and general surgery. Anesth Analg. 2009;109(5):1534-1545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee LA, Roth S, Posner KL, et al. The American Society of Anesthesiologists Postoperative Visual Loss Registry: analysis of 93 spine surgery cases with postoperative visual loss. Anesthesiology. 2006;105(4):652-659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Blindness Practice advisory for perioperative visual loss associated with spine surgery: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Blindness. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(6):1319-1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O'Leary CE. Informed consent for anesthesia: has the time come for a separate written consent document. American Society of Anethesiology Web site Published July 2006. http://www.asahq.org/Knowledge-Base/Ethics-and-Medicolegal-Issues/ASA/Informed-Consent-for-Anesthesia.aspx Accessed June 20, 2011

- 5. Clopper CJ, Pearson ES. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika. 1934;26(4):404-413 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Salgo v. Leland Stanford etc. Bd. Trustees P. 2d. Vol 317: (Cal: Court of Appeals, 1st Appellate Dist, 1st Div; 1957:170). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liang BA, Truog RD, Waisel DB. What needs to be said? Informed consent in the context of spinal anesthesia. J Clin Anesth. 1996;8(6):525-527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prosser WL, Keeton WP, Dobbs DB, Keeton RE, Owen DG. Prosser and Keeton on the Law of Torts. 5th ed. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co; 1984:32 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stevens WR, Glazer PA, Kelley SD, Lietman TM, Bradford DS. Ophthalmic complications after spinal surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(12):1319-1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chang SH, Miller NR. The incidence of vision loss due to perioperative ischemic optic neuropathy associated with spine surgery: the Johns Hopkins Hospital Experience. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(11):1299-1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shaw PJ, Bates D, Cartlidge NE, et al. Neuro-ophthalmological complications of coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Acta Neurol Scand. 1987;76(1):1-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.