Abstract

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), also called human herpesvirus 8, belongs to the gamma herpesviruses and is the etiological agent of Kaposi’s sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and some types of multicentric Castleman’s disease. In vivo, KSHV mainly infects B cells and endothelial cells. The interactions between KSHV and its host cells determine the outcome of viral infection and subsequent viral pathogenesis. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, non-coding RNAs that are important in fine-tuning cellular signaling. During infection, KSHV modulates the expression profiles and/or functions of a number of host miRNAs, for example hsa-miR-132 and hsa-miR-146a. Meanwhile, KSHV itself encodes 12 pre-miRNAs, including miR-K12-11, which is the functional ortholog of the host miR-155. A number of cellular and viral targets of deregulated cellular miRNAs and viral miRNAs are found in KSHV-infected cells, which suggests that miRNAs may be important in mediating KSHV–host interactions. In this review, we summarize our current understanding of how KSHV modulates the expression and/or functions of host miRNAs; we review in detail the functions of miR-K12-11 as the ortholog of miR-155; and we examine the functions of viral miRNAs in KSHV life cycle control, immune evasion, and pathogenesis.

Keywords: KSHV, microRNA

Introduction

The human tumor virus Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), also called human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8), is the etiological agent of Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), the most common malignance in AIDS patients, primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), and some types of multicentric Castleman’s disease (MCD; Chang et al., 1994; Cesarman et al., 1995; Soulier et al., 1995). The outcomes of viral infection and viral pathogenesis are determined by interactions between KSHV and host cells. Like all other herpesviruses, KSHV has two life cycle phases: latency and lytic replication. Only a few viral genes, such as latency-associated nuclear antigen [LANA, open reading frame (ORF) 73], viral cyclin (vCyclin, ORF72), and viral FLIP (vFLIP, ORF71), are expressed during latent infection and drive host cells proliferation and prevent apoptosis. Lytic transcripts, such as ORFK1, viral interleukin-6 (vIL-6, ORFK2), and viral G protein-coupled receptor (vGPCR) contribute to initiating angiogenesis and inflammatory lesions in host cells, and ultimately KS (Mesri et al., 2010). Both latent and lytic genes contribute to KSHV pathogenesis. Although a large number of diverse microRNAs (miRNAs) with potential regulatory functions exist in cell types from several different species (Lagos-Quintana et al., 2001; Lau et al., 2001; Lee and Ambros, 2001), their role in virus–host interactions was not investigated until the recent discovery of virus-encoded miRNAs (Pfeffer et al., 2004). Here we review our current understanding of the roles of both virally encoded and cellular miRNAs in KSHV virus–host interactions. Because of conserved similarities among the herpesvirus family, some of these examples might also apply to other viruses in this family.

The Biogenesis of Host and Viral miRNAs

MicroRNAs are approximately 22 nucleotide (nt)-long non-coding RNAs with regulatory functions that are expressed by all multicellular eukaryotes (Bartel, 2009). In the canonical pathway for miRNAs biogenesis, primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) that form an imperfect stem-loop with a hairpin bulge are first transcribed by RNA Pol II from miRNA genes. These pri-miRNAs are then processed by microprocessor which is composed of the RNase III enzyme Drosha and its co-factor DGCR8. The processed products called precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) have a hairpin structure of ∼70 nts and are exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm by a Ran GTPase called Exportin-5. In the cytoplasm, the stem-loops of pre-miRNAs are further cleaved by another RNase III, Dicer, and the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-binding protein TRBP leaving a ∼22-nt RNA duplex. Often, one strand of the duplex is preferentially incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The other strand, known as miRNA star (miRNA*) or the passenger strand, is often degraded. RISC loaded with mature miRNA is subsequently guided by the miRNA to pair with target transcripts at the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) and induces posttranscriptional silencing (Bartel, 2009). In addition to the canonical pathways for generating miRNAs, some non-canonical ways to produce miRNA also exist (see review Yang and Lai, 2011).

Since Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) was first shown to encode several miRNAs (Pfeffer et al., 2004), many other viruses, especially herpesviruses including KSHV, have also been demonstrated to encode their own miRNAs. Most known viral miRNA genes are expressed using the canonical pathways of miRNA biogenesis with only two exceptions for γ-herpesvirus. In murine γ-herpesvirus type 68 (also known as murid herpesvirus 4), miRNA genes embedded in tRNA-like transcripts are transcribed by RNA Pol III instead of Pol II (Bogerd et al., 2010; Diebel et al., 2010). Another exception is from Herpesvirus saimiri (HVS)-encoded miRNAs. Three of the seven HVS-encoded Sm-class U RNAs (HSURs) give rise to six mature miRNAs derived from hairpin structures located immediately downstream of the 3′ end processing signals. The processing of these miRNAs is not dependent on the microprocessor complex. Instead, the Integrator complex is required to generate the 3′ end of HSURs and the pre-miRNA hairpins. Pre-miRNAs are subsequently exported to the cytoplasm by Exportin-5, and Dicer is required to generate mature viral miRNAs (Cazalla et al., 2011).

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes 12 pre-miRNAs that produce 25 mature miRNAs (Summarized in Table 1) through the canonical pathway for miRNA biogenesis (Cai et al., 2005; Pfeffer et al., 2005; Samols et al., 2005; Grundhoff et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2010; Umbach and Cullen, 2010). Ten of these miRNA precursors are organized into clusters within the latent genes locus. The other two pre-miRNAs (miR-K12-10, miR-K12-12) are located within the 3′UTR of ORF K12. All these viral miRNAs share two common promoters with the viral latent transcripts (Pearce et al., 2005; Cai and Cullen, 2006). Interestingly, the primary sequences of both miR-K12-10 and miR-K12-12 can be cleaved by Drosha in cis, which results in reduced transcript K12 and decreased K12 protein expression (Lin and Sullivan, 2011). KSHV-encoded miRNAs were initially discovered in viral latency (Cai et al., 2005; Pfeffer et al., 2005; Samols et al., 2005; Grundhoff et al., 2006), but are also detected in lytic replication (Lin et al., 2010; Umbach and Cullen, 2010). The expression levels of some viral miRNAs are even higher in the lytic phase compared to the latent phase (Lin et al., 2010; Umbach and Cullen, 2010). It will be interesting in the future to determine the reason for this differential expression pattern in the viral life cycle.

Table 1.

List of KSHV-encoded miRNAs.

| Name | Sequence | Genome position¶ |

|---|---|---|

| KSHV-miR-K12-1-5p | AUUACAGGAAACUGGGUGUAAG | 122138–122159 |

| AUUACAGGAAACUGGGUGUAAGC | ||

| AUUACAGGAAACUGGGUGUAAGCU | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-1-3p | GCAGCACCUGUUUCCUGCAACC | 122100–122121 |

| KSHV-miR-K12-2-5p | AACUGUAGUCCGGGUCGAUCU | 121978–121998 |

| AACUGUAGUCCGGGUCGAUCUG | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-2-3p | GAUCUUCCAGGGCUAGAGCUG | 121935–121955 |

| GAUCUUCCAGGGCUAGAGCUGC | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-3-5p | UCACAUUCUGAGGACGGCAGC | 121836–121856 |

| UCACAUUCUGAGGACGGCAGCG | ||

| UCACAUUCUGAGGACGGCAGCGA | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-3-3p | UCGCGGUCACAGAAUGUG | 121797–121814 |

| GUCGCGGUCACAGAAUGU | ||

| UCGCGGUCACAGAAUGUGACA | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-4-5p | AGCUAAACCGCAGUACUCUAG | 121704–121724 |

| AGCUAAACCGCAGUACUCUAGG | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-4-3p | UAGAAUACUGAGGCCUAGCUG | 121666–121686 |

| UAGAAUACUGAGGCCUAGCUGA | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-5-5p | AGGUAGUCCCUGGUGCCCUAA | 121554–121574 |

| AGGUAGUCCCUGGUGCCCUAAG | ||

| UAGGUAGUCCCUGGUGCCCUAA | ||

| UAGGUAGUCCCUGGUGCCCUAAG | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-5-3p | UAGGAUGCCUGGAACUUGCC | 121516–121535 |

| UAGGAUGCCUGGAACUUGCCGG | ||

| UAGGAUGCCUGGAACUUGCCGGU | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-6-5p | CCAGCAGCACCUAAUCCAUCG | 121045–121065 |

| CCAGCAGCACCUAAUCCAUCGG | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-6-3p | UGAUGGUUUUCGGGCUGUUGAG | 121012–121033 |

| UGAUGGUUUUCGGGCUGUUGAGC | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-7-5p | AGCGCCACCGGACGGGGAUUUA | 120646–120667 |

| AGCGCCACCGGACGGGGAUUUAU | ||

| AGCGCCACCGGACGGGGAUUUAUG | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-7-3p | UGAUCCCAUGUUGCUGGCGC | 120608–120627 |

| UGAUCCCAUGUUGCUGGCGCU | ||

| UGAUCCCAUGUUGCUGGCGCUC | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-8-5p | ACUCCCUCACUAACGCCCCGC | 120234–120254 |

| ACUCCCUCACUAACGCCCCGCU | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-8-3p | CUAGGCGCGACUGAGAGAG | 120196–120214 |

| CUAGGCGCGACUGAGAGAGC | ||

| CUAGGCGCGACUGAGAGAGCA | ||

| CUAGGCGCGACUGAGAGAGCAC | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-9-5p | ACCCAGCUGCGUAAACCCCGC | 119587–119607 |

| ACCCAGCUGCGUAAACCCCGCU | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-9-3p | CUGGGUAUACGCAGCUGCGUA | 119553–119573 |

| CUGGGUAUACGCAGCUGCGUAA | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-10a-5p | GGCUUGGGGCGAUACCACCACU | 118116–118137 |

| KSHV-miR-K12-10a-3p | UAGUGUUGUCCCCCCGAGUGG | 118077–118097 |

| UAGUGUUGUCCCCCCGAGUGGC | ||

| UUAGUGUUGUCCCCCCGAGUGG | ||

| UUAGUGUUGUCCCCCCGAGUGGC | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-10b-3p | UGGUGUUGUCCCCCCGAGUGGC | 118077–118097 |

| UUGGUGUUGUCCCCCCGAGUGG | ||

| UUGGUGUUGUCCCCCCGAGUGG | ||

| UUGGUGUUGUCCCCCCGAGUGGC | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-11-5p | GGUCACAGCUUAAACAUUUC | 120868–120887 |

| GGUCACAGCUUAAACAUUUCUA | ||

| GGUCACAGCUUAAACAUUUCUAG | ||

| GGUCACAGCUUAAACAUUUCUAGG | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-11-3p | UUAAUGCUUAGCCUGUGUCCGA | 120827–120848 |

| KSHV-miR-K12-12-5p | AACCAGGCCACCAUUCCUCUC | 117837–117857 |

| AACCAGGCCACCAUUCCUCUCC | ||

| AACCAGGCCACCAUUCCUCUCCG | ||

| UCAACCAGGCCACCAUUCCUC | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-12-3p | UGGGGGAGGGUGCCCUGGUUGA | 117798–117819 |

Most abundant forms of KSHV mature miRNAs were listed here.

¶ All positions indicated here were the positions of the sequences listed in the first lines and were referenced in KSHV genome (accession number: AF148805).

miRNAs as a Mediator in the Virus–Host Interaction Network

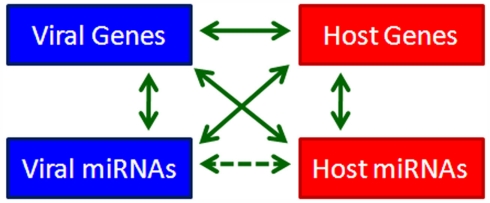

Since the discovery of miRNA, we have known that it modulates gene expression post-transcriptionally through targeting the 3′UTRs of target genes or through inducing degradation of target gene transcripts (Lee et al., 1993). The expression of miRNAs themselves is also strictly regulated through different mechanisms. The discovery of virus-encoded miRNAs in herpesviruses provides us with an opportunity to reevaluate the interactions between the virus and its host from a new perspective. Based on the profound regulatory effects of miRNAs, we propose a four-component model to depict viral–host interactions. In this model, viral genes, viral miRNAs, host genes, and host miRNAs are four mediators of cellular signaling that regulate each others’ expression by various means (Figure 1). This complicated and elaborate regulatory network mediating virus–host interactions determines the outcome of virus infection. Since herpesviruses establish long-term latency in the cell, they have multiple strategies to dominate the signaling network to favor long-term infection. The importance of virally hijacked host miRNAs and deregulated viral miRNAs in herpesvirus infection and pathogenesis has turned out to be beyond our expectations. In the following section, we review the critical roles of both cellular and viral miRNAs in KSHV infection (Summarized in Table 2).

Figure 1.

A four-component model for viral–host interaction.

Table 2.

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded miRNAs as mediators in virus–host interactions.

| Category | miRNA | Gene | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viral miRNAs target viral genes | KSHV-miR-K12-9-5p, KSHV-miR-K12-7-5p, KSHV-miR-K12-5 | RTA | Repress RTA to maintain latency | Bellare and Ganem (2009), Lu et al. (2010b), Lin et al. (2011) |

| Viral miRNAs target cellular genes | KSHV-miR-K12-1 | IκB | Inhibit RTA through NF-κB signaling to maintain latency | Lei et al. (2010) |

| p21 | Repress growth arrest | Gottwein and Cullen (2010) | ||

| MAF | Facilitate cell trans-differentiation | Hansen et al. (2010) | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-3 | NFIB | Suppress RTA through NFIB to maintain latency | Lu et al. (2010a) | |

| CEBPB | Induce IL-6 and IL-10 expression via inhibiting CEBPB | Qin et al. (2009) | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-4-5p | RBL2 | Alter epigenetics by derepressing RBL2-DNMT pathway | Lu et al. (2010b) | |

| KSHV-miR-K12-6-5p | MAF | Facilitate cell trans-differentiation | Hansen et al. (2010) | |

| KSHV-miR-K12-7 | MICB | Suppress cell-mediated immunity | Nachmani et al. (2009) | |

| CEBPB | Induce IL-6 and IL-10 expression via inhibiting CEBPB | Qin et al. (2009) | ||

| KSHV-miR-K12-10a | TWEAKR | Anti-apoptosis/inflammation | Abend et al. (2010) | |

| KSHV-miR-K12-11 | IKKε | Repress IFN response | Liang et al. (2011) | |

| SMAD5 | Promote cell survival through repressing SMAD5 mediated TGF-β signaling | Liu et al. (2011) | ||

| MAF | Facilitate cell trans-differentiation | Hansen et al. (2010) | ||

| BACH1 | Gottwein et al. (2007), Skalsky et al. (2007) | |||

| KSHV-miR-cluster | THBS1 | Angiogenesis | Samols et al. (2007) | |

| BCLF1 | Inhibit caspase and promote viral replication | Ziegelbauer et al. (2009) | ||

| Cellular miRNAs target viral genes | hsa-miR-1293 | vIL-6 | Restrict viral pathogenesis | Kang et al. (2011) |

| Cellular miRNAs target cellular genes | hsa-miR-608 | hIL-6 | Restrict viral pathogenesis | Kang et al. (2011) |

| hsa-miR-132 | p300 | Immune evasion | Lagos et al. (2010) | |

| Viral genes target viral miRNAs | KSHV-miR-K12-9-5p | PAN | Predicted | |

| Viral genes target cellular miRNAs | hsa-miR-146a | vFLIP | Repress CXCR4 | Cazalla et al. (2010), Punj et al. (2010) |

| Cellular genes target viral miRNAs | KSHV-miR-K12-10, KSHV-miR-K12-12 | Drosha | Regulate miRNAs expression and facilitate cell survival via promoting kaposin B expression | Lin and Sullivan (2011) |

| Cellular genes target cellular miRNAs | hsa-miR-132 | CREB/p300 | Induce hsa-miR-132 expression during early viral infection | Lagos et al. (2010) |

KSHV Modulates the Expression Profile and/or Function of Host miRNAs

To date, more than 1400 mature miRNAs have been identified in humans (Kozomara and Griffiths-Jones, 2011), forming a delicate miRNA system that is critical for fine-tuning the cellular signaling network. The expression profile of human miRNAs varies significantly among different cell types and can be modulated by many cellular events. Increasing evidence suggests that virus infection can influence the expression profile of host miRNAs, resulting from either defensive host signaling against virus infection or viral hijacking to favor virus infection. Therefore, host miRNAs are important in balancing virus–host interactions. Viral gene products regulate host miRNA expression through gene alteration, transcription regulation or processing, directly or indirectly. In some cases they even modulate the function of host miRNAs. When herpesviruses establish long-term latency in the host cells, virus-specific host miRNAs expression pattern, or miRNAs signature, is established. Thus, the host miRNA system is an important tool that is hijacked by the herpesvirus for viral latency maintenance and viral pathogenesis.

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus mainly infects human endothelial cells (ECs) and B cells in vivo. Therefore, knowing the effects of KSHV infection on the host miRNA expression profiles of these two cell types will be interesting. Using quantitative PCR (qPCR)-based arrays, O’Hara et al. (2008) identified 68 miRNAs specifically expressed in PEL cell lines rather than in KSHV non-related lymphoma cell lines and tonsil tissues. However, the question remains whether these PEL-specific miRNAs are regulated directly by KSHV gene products or are the consequence of long-term infection and oncogenesis. To answer this question, in a later study, O’Hara et al. profiled PEL cell lines, KSHV-infected ECs, uninfected ECs, and primary KS biopsies for host miRNAs expression using a qPCR-based array. After adjustment for multiple comparisons, they identified 18 KSHV-regulated miRNAs. Moreover, they demonstrated that the tumor suppressor miRNAs in the let-7 family and miR-220/221 are downregulated in KSHV-associated cancers, including PEL and KS (O’Hara et al., 2009).

To determine the host miRNA profile during early KSHV infection, Lagos et al. detected host miRNA expression at 6 and 72 h post-KSHV infection of lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) using an miRNA microarray. They identified two groups of miRNAs induced during primary KSHV infection. The first group consisted of nine miRNAs that reached their peak expression at 6 h post-infection, including hsa-miR-146a, hsa-miR-31, and hsa-miR-132. Expression levels of five miRNAs from the second group, including hsa-miR-193a and hsa-let-7i, steadily increased over the 72 post-infection hours (Lagos et al., 2010).

Although the functions of human miRNAs have been extensively studied and KSHV clearly regulates host miRNA expression, the roles of host miRNAs in KSHV infection are less well understood than the functions of the viral miRNAs. Based on a limited number of studies, we infer that KSHV hijacks the host miRNA system to favor infection and pathogenesis.

Lagos et al. showed that KSHV-induced hsa-miR-132 expression via a CREB-dependent pathway. The miRNA hsa-miR-132 negatively regulates interferon pathways by targeting the p300 transcriptional co-activator to facilitate viral replication. Interestingly, they show a similar function for hsa-miR-132 during infection of monocytes with herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV). Therefore, induction of hsa-miR-132 might be a common strategy for herpesvirus to control innate immunity at early stage of infection (Lagos et al., 2010). However, more extensive studies are needed to clarify the common signaling pathway that is responsible for CREB-mediated hsa-miR-132 activation.

Another host miRNA upregulated by KSHV is hsa-miR-146a (Lagos et al., 2010; Punj et al., 2010). Punj et al. showed that vFLIP is responsible for hsa-miR-146a upregulation. They identified two NF-κB sites in the promoter of hsa-miR-146a that are essential for its activation by vFLIP. Upregulation of hsa-miR-146a suppresses its target CXCR4; downregulation of CXCR4 might contribute to KS development by promoting premature release of KSHV-infected endothelial progenitors into circulation (Punj et al., 2010). Indeed, hsa-miR-146a is also reported to be upregulated by EBV LMP1, and hsa-miR-146a might function in a negative feedback loop to modulate the intensity and/or duration of the interferon response (Cameron et al., 2008). Therefore, hsa-miR-146a might be another common host miRNA target of herpesvirus infection.

Tsai et al. showed that K15M (the minor form of KSHV K15) induces expression of hsa-miR-21 and hsa-miR-31. Knocking down both of these miRNAs eliminates K15M-induced cell motility. Therefore, K15M might contribute to KSHV-mediated tumor metastasis and angiogenesis via regulation of hsa-miR-21 and hsa-miR-31 (Tsai et al., 2009). In another study, Wu et al. explored the genes and miRNAs involved in KSHV-induced cell motility by combining gene and miRNA profile data. They showed that KSHV induces global changes of miRNA expression in LECs. Specifically, the hsa-miR-221/hsa-miR-222 cluster is downregulated, whereas hsa-miR-31 is upregulated. Both LANA and Kaposin B repress the expression of the hsa-miR-221/hsa-miR-222 cluster, which results in upregulation of their target gene ETS1 or ETS2 and is sufficient to induce EC migration. In contrast, upregulated hsa-miR-31 stimulates EC migration by reduction its target gene FAT4 (Wu et al., 2011).

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus not only modulates host miRNAs expression, but also modulates the function of some host miRNAs. Kang et al. showed direct repression of vIL-6 by hsa-miR-1293 and repression of hIL-6 by hsa-miR-608. They also found that KSHV ORF57 and hsa-miR-1293/hsa-miR-608 compete for the same binding site on vIL-6/hIL-6 mRNA. ORF57 binding results in escape of viral and human IL-6 from miRNA-mediated suppression, contributing to KSHV pathogenesis (Kang et al., 2010, 2011).

Cazalla et al. (2010) showed that the HVS-encoded non-coding RNA, HSUR1, directs host miR-27 degradation and subsequent reduction of miR-27 target genes. This evidence also supports the hypothesis that viral genes can regulate host miRNA expression and function.

The function of host miRNAs in KSHV infection is increasingly a topic of interest in the field. More KSHV-regulated host miRNAs are being identified, and their function is usually clearer than that of viral miRNAs. We can therefore apply knowledge about other host miRNAs to the KSHV field to help understand the functions of KSHV-hijacked host miRNAs in KSHV infection and related pathogenesis.

KSHV Encodes Orthologs of Host miRNAs

Many KSHV-encoded ORFs are pirated from the host genome. An interesting question is whether KSHV also pirates pre-miRNA genes from the host genome. Early in the identification of KSHV miRNAs, two independent studies reported that miR-K12-11 is the ortholog of host hsa-miR-155 and these miRNAs have identical seed sequence (Gottwein et al., 2007; Skalsky et al., 2007). Hsa-miR-155 is a multifunctional miRNA that is important in immunity, hematopoiesis, inflammation, and oncogenesis (McClure and Sullivan, 2008). Not only miR-K12-11, but also miR-M4, which is encoded by the highly oncogenic Marek’s disease virus of chickens, is a functional ortholog of hsa-miR-155(Zhao et al., 2009). EBV does not encode a hsa-miR-155 ortholog. Instead, EBV-induced hsa-miR-155 expression by LMP1 and hsa-miR-155 is important in EBV viral pathogenesis (Motsch et al., 2007; Gatto et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2008). Of note, hsa-miR-155 is downregulated in KSHV-infected cells (Gottwein et al., 2007; Skalsky et al., 2007); therefore KSHV might encode miR-K12-11 to replace the function of its ortholog, hsa-miR-155.

Since miR-K12-11 shares an identical seed sequence with hsa-miR-155, these two miRNAs may have similar functions and target the same genes. Gottwein et al. (2007) used a range of assays to show that expression of physiological levels of miR-K12-11 or hsa-miR-155 results in the downregulation of an extensive set of common mRNA targets, including genes with known roles in cell growth regulation, for example BACH1. Moreover, Qin et al. (2010) found that KSHV-encoded microRNAs upregulate xCT expression in macrophages and ECs, largely through miR-K12-11 suppression of BACH1, a negative regulator of transcription that recognizes antioxidant response elements within gene promoters.

To compare miR-K12-11 and hsa-miR-155 functions in vivo, Boss et al. used a foamy virus vector to express the miRNAs in human hematopoietic progenitors and performed immune reconstitutions in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2Rγ (null) mice. They found that ectopic expression of miR-K12-11 or hsa-miR-155 targeting C/EBPβ, leads to a significant expansion of the CD19 (+) B-cell population in the spleen. This in vivo study validates miR-K12-11 as a functional ortholog of hsa-miR-155 in the context of hematopoiesis (Boss et al., 2011).

Our study indicated that miR-K12-11 is involved in attenuating interferon signaling and contributing to KSHV latency maintenance through targeting I-kappa-B kinase epsilon (IKKε). We demonstrated that miR-K12-11 attenuated IFN signaling by decreasing IKKε-mediated IRF3/IRF7 phosphorylation. We also demonstrated that IKKε enhances KSHV reactivation synergistically with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate treatment. Moreover, inhibition of miR-K12-11 enhances KSHV reactivation induced by vesicular stomatitis virus infection. Taken together, our findings suggest that miR-K12-11 can contribute to maintenance of KSHV latency by targeting IKKε (Liang et al., 2011).

More recently, we demonstrated that ectopic expression of miR-K12-11 downregulates TGF-β signaling and facilitates cell proliferation upon TGF-β treatment by directly targeting SMAD5. Our findings highlight a novel mechanism in which miR-K12-11 downregulates TGF-β signaling, and suggests that viral miRNAs and proteins may exert a dichotomous regulation in virus-induced oncogenesis by targeting the same signaling pathway (Liu et al., 2011).

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus exploits miR-K12-11 to tap into a host miRNA regulatory network (McClure and Sullivan, 2008). Based on the important functions of hsa-miR-155, we believe that miR-K12-11 is of particular importance in KSHV infection and pathogenesis.

Using Target Scan5.0 (Lewis et al., 2005), we found that miR-K12-2 shares the same seed sequence as miR-1183 (unpublished data). The function of miR-1183 is poorly understood. Further study is needed to confirm whether miR-K12-2 is the true ortholog of miR-1183, and to determine the function of these two miRNAs in KSHV infection.

Functions of Viral miRNA in KSHV Infection

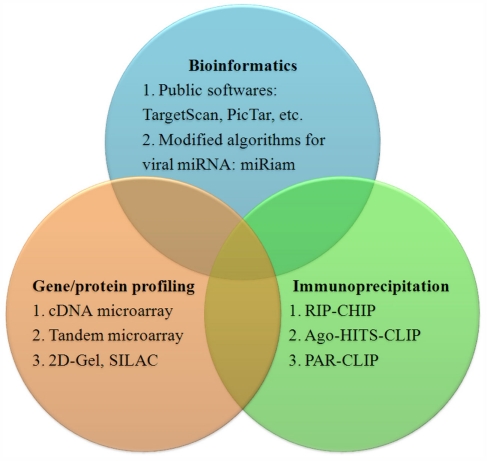

Identifying targets of KSHV-encoded miRNA

Studying the function of a particular miRNA can begin by simply predicting targets using software such as TargetScan, PicTar, or DIANA MicroT (Krek et al., 2005; Lewis et al., 2005; Maragkakis et al., 2009). These programs are based on the qualitative and quantitative properties and the thermodynamic nature of the miRNA/target heteroduplex (Lieber and Haas, 2011). However, most of these algorithms are not optimized for viral miRNAs and can yield many false-positive viral miRNA targets.

Laganà and colleagues developed the program miRiam, modified for prediction of viral miRNA targets. miRiam uses both thermodynamic features and empirical constraints to predict interactions between viral miRNAs and human targets. It exploits target mRNA secondary structure accessibility and interaction rules, inferred from validated miRNA/mRNA pairs. A set of target genes for EBV and KSHV miRNAs that are involved in apoptosis and cell-cycle regulation was identified using miRiam (Lagana et al., 2010).

In addition to bioinformatic methods, high throughput gene profile technologies such as cDNA microarrays can be used to identify viral miRNA targets. In an early study, Samols et al. (2007) performed gene expression profiling in cells stably expressing KSHV-encoded miRNAs, and identified a set of 81 genes whose expression was significantly changed in the presence of miRNAs. To increase the accuracy of this method, Ziegelbauer et al. developed a tandem array-based expression screening method to identify KSHV miRNA targets. Their approach is based on multiple screens that examine small changes in transcript abundance under different conditions of miRNA expression or inhibition, followed by searching the identified transcripts for seed sequence matches. They identified Bcl2-associated factor BCLAF1 as a target for multiple KSHV miRNAs (Ziegelbauer et al., 2009). In addition to cDNA microarrays, protein profiling technologies such as stable isotope-labeling by amino acids, or SILAC, in cell culture are also being used to identify miRNA targets (Vinther et al., 2006).

A more direct identification of miRNA targets can be achieved by immunoprecipitation (IP) of Argonaute protein-containing complexes followed by microarray analysis of the associated mRNAs, in a method called RIP-chip (Keene et al., 2006; Beitzinger et al., 2007). Dolken et al. (2010) used Ago2-based RIP-chip to identify transcripts targeted by KSHV miRNAs (n = 114), EBV miRNAs (n = 44), and cellular miRNAs (n = 2337) in six latently infected or stably transduced human B-cell lines. Now, high throughput sequencing of RNA isolated by cross-linking IP of Argonaute-containing complexes, or Ago-HITS-CLIP; (Chi et al., 2009) and photoactivatable, ribonucleoside-enhanced cross-linking and IP, or PAR-CLIP (Hafner et al., 2010), have been developed to identify targets for host and viral miRNA more precisely. A summary of methods to identify miRNA targets is in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Methods to identify miRNA targets.

KSHV miRNAs and viral life cycle control

The idea that viral miRNA is involved in viral latency regulation first came from the finding that SV40-encoded miR-S1 targets the viral large T-antigen (Sullivan et al., 2005). This results in reduced expression of viral T-antigen but not infectious virus relative to that generated from a miRNA deletion mutant (Sullivan et al., 2005). In HSV-1, studies showed that two miRNAs encoded by HSV-1, miR-H2-3p, and miR-H6, facilitate the establishment and maintenance of viral latency by targeting viral immediate early transactivators ICP0 and ICP4.5, respectively (Umbach et al., 2008). Similar results in HSV-2, found that miR-β contributes to viral latency control through silencing ICP0 expression (Tang et al., 2009). Studies in HCMV showed that virus-encoded miR-UL112-1 controls viral latency by inhibiting the viral immediate early gene 72 (IE72; Murphy et al., 2008). The authors predicted that other herpesviruses might use a similar strategy to control viral latency.

Studies from KSHV-encoded miRNAs confirmed this hypothesis. Several miRNAs have been found to affect the expression level of the viral immediate early gene replication and transcription activator (RTA), either directly (Bellare and Ganem, 2009; Lu et al., 2010b; Lin et al., 2011) or indirectly (Lei et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2010a). Bellare et al. using miRNA mimics or specific inhibitors for KSHV-encoded miRNAs and reporter constructs containing the RTA 3′UTR, found that miR-K12-9-5p targets RTA directly, and depends on the canonical 6-mer seed match site. When this miRNA was inhibited by a specific antagomir, a moderate increase in lytic replication was observed (Bellare and Ganem, 2009). A second study by Lu et al. (2010b) using constructs expressing KSHV-encoded miRNAs and a reporter containing the RTA 3′UTR demonstrated that miR-K12-5 represses RTA expression, although the RTA 3′UTR lacks a canonical miR-K12-5 seed sequence. In another study by us, a reporter containing the RTA 3′UTR and constructs expressing all 12 pre-miRNAs, miR-K12-9, and miR-K12-7-5p were found to target RTA directly. miR-K12-7-5p, targeting RTA, was shown to be mediated by a 7-mer seed match site. Additionally, endogenous RTA expression level was reduced by ectopically overexpressing miR-K12-7 and derepressed using an miR-K12-7-5p inhibitor. A decrease in viral particles was observed when miR-K12-7 was overexpressed (Lin et al., 2011). Lei et al. used an miR-cluster deletion mutant virus to determine that miR-K12-1 represses IκB, an inhibitor of NFκB. Inhibition of IκB leads to NFκB activation, which suppresses RTA to facilitate viral latency control (Lei et al., 2010). Lu et al. (2010a), using a lentivirus expressing individual KSHV miRNA, found that miR-K12-3 reduces RTA mRNA levels by targeting NFIB directly. Further studies showed a putative NFIB-binding site is located in the RTA promoter and shRNA knockdown of NFIB resulted in decreased RTA expression.

Taken together, the evidence suggests that multiple KSHV-encoded miRNAs are involved in viral latency maintenance and herpes viral latency control is important and a complex process. These data support the hypothesis that conservation among herpesviruses allows them to use viral miRNA(s) to target immediate early genes to control viral latency (Murphy et al., 2008).

KSHV miRNA and immune regulation

To establish long-term latent infection in the host cell, KSHV has developed multiple strategies to evade the host innate and adaptive immunity (Areste and Blackbourn, 2009). Some studies suggest that KSHV-encoded miRNAs are involved in immune regulation and favor KSHV infection. For example, several herpesviruses, including KSHV, encode an miRNA that targets the MHC class I-related chain B (MICB), which is a stress-induced ligand recognized by the NKG2D receptor expressed by NK cells and CD8+ T-cells. In 2007, Stern-Ginossar et al. identified that HCMV miRNA miR-UL112-1 targets MICB. They showed that HCMV-miR-UL112 specifically downregulates MICB expression during viral infection, leading to decreased binding of NKG2D and reduced killing by NK cells (Stern-Ginossar et al., 2007). They further showed that both EBV miR-BART2-5p and KSHV-miR-K12-7 regulate MICB expression (Nachmani et al., 2009). Moreover, Thomas et al. showed that the KSHV immune evasion gene, K5, reduces cell-surface expression of the NKG2D ligands MHC class I-related chain A (MICA) and MICB, probably by K5-mediated ubiquitylation, which signals internalization and causes a potent reduction in NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. These studies suggested that NKG2D ligands are common targets for both KSHV miRNA and ORF for evading NK cell antiviral function (Thomas et al., 2008). Another example is that miR-K12-11 directly targets IKKε, an important modulator of IFN signaling.

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus miRNAs also regulate the host immune response by modulating expression of cytokines. Abend et al. demonstrated that miR-K12-10a robustly downregulates the expression of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) receptor (TWEAKR). The downregulation of TWEAKR by miR-K10a in primary human ECs results in a decrease in expression of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-8 and monocyte chemo attractant protein 1 in response to TWEAK. This protects cells from apoptosis and suppresses a proinflammatory response (Abend et al., 2010). Qin et al. (2009) demonstrated that miR-K12-3 and miR-K12-7 target C/EBPβ p20 (LIP), a negative transcriptional regulator of IL-6 and IL-10, and induces expression of IL-6 and IL-10 in macrophages. These cytokines have broad functions in oncogenesis and immune suppression. The function of miR-K12-3 and miR-K12-7 in immune regulation needs to be further studied (Boss and Renne, 2011).

KSHV miRNAs and viral pathogenesis

In addition to viral life cycle control and viral immune evasion, KSHV-encoded miRNAs have other functions directly related to pathogenesis.

Samols et al. (2007) identified THBS1 as a target of several KSHV miRNAs. THBS1 is a strong tumor suppressor and anti-angiogenic factor. They proposed that KSHV-encoded miRNAs contribute directly to pathogenesis by downregulation of THBS1, promoting cell adhesion, migration, and angiogenesis. Gottwein et al. reported that miR-K1 directly targets the cellular cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21, strongly attenuating the cell-cycle arrest that normally occurs upon p53 activation. They suggested that this KSHV miRNA likely contributes to the oncogenic potential of KSHV (Gottwein and Cullen, 2010). Hansen et al. demonstrated that multiple KSHV miRNAs contribute to virally induced reprogramming by silencing the cellular transcription factor MAF, which prevents expression of blood vascular endothelial cells (BECs) specific genes, thereby maintaining the differentiation status of LECs. These findings demonstrate that KSHV miRNAs could influence the differentiation status of infected cells, contributing to KSHV-induced oncogenesis (Hansen et al., 2010).

Using developing systems biology methods, the target list of KSHV miRNAs is rapidly increasing (Lieber and Haas, 2011). The functions of KSHV miRNAs include, but are not limited to, viral life cycle control, immune regulation, and pathogenesis. KSHV miRNAs are important mediators of viral–host interactions. Using viral miRNA knockout viruses will allow studies that lead to an overall understanding of the functions of unique KSHV miRNAs.

Conclusion

MicroRNAs are small, regulatory, non-coding RNAs with diverse functions in fine-tuning cellular signaling. KSHV modulates host miRNA expression and also encodes 25 mature viral miRNAs. Increasing evidence suggests that both virally hijacked host miRNAs and dysregulated viral miRNAs are important in KSHV life cycle control, immune evasion, and pathogenesis. In this review, we propose a four-component model for viral–host interactions (Figure 1). Existing evidence supports this model (Table 2), with examples for almost every action mode in this model of virus–host interactions. Using RNAhybrid (http://bibiserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/rnahybrid/), we predict, according to our model, that KSHV-encoded polyadenylated nuclear RNA (PAN, also known as nut-1) functions as an miRNA sponge to inhibit KSHV-encoded miR-K12-9-5p. Based on the profound effects of miRNAs as mediators in virus–host interactions, we believe they will become emerging therapy targets for treating KSHV infection and KSHV-related malignancies.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the 100 Talent Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Natural Science Foundation of China (30770098 and 30970154), and National Basic Research Program of China (2011CB504805 and 2012CB519002) to Ke Lan.

References

- Abend J. R., Uldrick T., Ziegelbauer J. M. (2010). Regulation of tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis receptor protein (TWEAKR) expression by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus microRNA prevents TWEAK-induced apoptosis and inflammatory cytokine expression. J. Virol. 84, 12139–12151 10.1128/JVI.00884-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Areste C., Blackbourn D. J. (2009). Modulation of the immune system by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Trends Microbiol. 17, 119–129 10.1016/j.tim.2008.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel D. P. (2009). MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136, 215–233 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitzinger M., Peters L., Zhu J. Y., Kremmer E., Meister G. (2007). Identification of human microRNA targets from isolated argonaute protein complexes. RNA Biol. 4, 76–84 10.4161/rna.4.2.4640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellare P., Ganem D. (2009). Regulation of KSHV lytic switch protein expression by a virus-encoded microRNA: an evolutionary adaptation that fine-tunes lytic reactivation. Cell Host Microbe 6, 570–575 10.1016/j.chom.2009.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogerd H. P., Karnowski H. W., Cai X., Shin J., Pohlers M., Cullen B. R. (2010). A mammalian herpesvirus uses noncanonical expression and processing mechanisms to generate viral microRNAs. Mol. Cell 37, 135–142 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss I. W., Nadeau P. E., Abbott J. R., Yang Y., Mergia A., Renne R. (2011). A Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded ortholog of microRNA miR-155 induces human splenic B-cell expansion in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2Rgammanull mice. J. Virol. 85, 9877–9886 10.1128/JVI.05558-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss I. W., Renne R. (2011). Viral miRNAs and immune evasion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1809, 623–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X., Cullen B. R. (2006). Transcriptional origin of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus microRNAs. J. Virol. 80, 2234–2242 10.1128/JVI.00689-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X., Lu S., Zhang Z., Gonzalez C. M., Damania B., Cullen B. R. (2005). Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus expresses an array of viral microRNAs in latently infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 5570–5575 10.1073/pnas.0408192102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J. E., Yin Q., Fewell C., Lacey M., Mcbride J., Wang X., Lin Z., Schaefer B. C., Flemington E. K. (2008). Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces cellular MicroRNA miR-146a, a modulator of lymphocyte signaling pathways. J. Virol. 82, 1946–1958 10.1128/JVI.00691-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazalla D., Xie M., Steitz J. A. (2011). A primate herpesvirus uses the integrator complex to generate viral microRNAs. Mol. Cell 43, 982–992 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazalla D., Yario T., Steitz J. A. (2010). Down-regulation of a host microRNA by a herpesvirus saimiri noncoding RNA. Science 328, 1563–1566 10.1126/science.1187197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesarman E., Chang Y., Moore P. S., Said J. W., Knowles D. M. (1995). Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 332, 1186–1191 10.1056/NEJM199505043321802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y., Cesarman E., Pessin M. S., Lee F., Culpepper J., Knowles D. M., Moore P. S. (1994). Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Science 266, 1865–1869 10.1126/science.7997879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi S. W., Zang J. B., Mele A., Darnell R. B. (2009). Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature 460, 479–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diebel K. W., Smith A. L., Van Dyk L. F. (2010). Mature and functional viral miRNAs transcribed from novel RNA polymerase III promoters. RNA 16, 170–185 10.1261/rna.1873910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolken L., Malterer G., Erhard F., Kothe S., Friedel C. C., Suffert G., Marcinowski L., Motsch N., Barth S., Beitzinger M., Lieber D., Bailer S. M., Hoffmann R., Ruzsics Z., Kremmer E., Pfeffer S., Zimmer R., Koszinowski U. H., Grasser F., Meister G., Haas J. (2010). Systematic analysis of viral and cellular microRNA targets in cells latently infected with human gamma-herpesviruses by RISC immunoprecipitation assay. Cell Host Microbe 7, 324–334 10.1016/j.chom.2010.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto G., Rossi A., Rossi D., Kroening S., Bonatti S., Mallardo M. (2008). Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 trans-activates miR-155 transcription through the NF-kappaB pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 6608–6619 10.1093/nar/gkn666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottwein E., Cullen B. R. (2010). A human herpesvirus microRNA inhibits p21 expression and attenuates p21-mediated cell cycle arrest. J. Virol. 84, 5229–5237 10.1128/JVI.02667-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottwein E., Mukherjee N., Sachse C., Frenzel C., Majoros W. H., Chi J. T., Braich R., Manoharan M., Soutschek J., Ohler U., Cullen B. R. (2007). A viral microRNA functions as an orthologue of cellular miR-155. Nature 450, 1096–1099 10.1038/nature05992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundhoff A., Sullivan C. S., Ganem D. (2006). A combined computational and microarray-based approach identifies novel microRNAs encoded by human gamma-herpesviruses. RNA 12, 733–750 10.1261/rna.2326106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner M., Landthaler M., Burger L., Khorshid M., Hausser J., Berninger P., Rothballer A., Ascano M., Jr., Jungkamp A. C., Munschauer M., Ulrich A., Wardle G. S., Dewell S., Zavolan M., Tuschl T. (2010). Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell 141, 129–141 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen A., Henderson S., Lagos D., Nikitenko L., Coulter E., Roberts S., Gratrix F., Plaisance K., Renne R., Bower M., Kellam P., Boshoff C. (2010). KSHV-encoded miRNAs target MAF to induce endothelial cell reprogramming. Genes Dev. 24, 195–205 10.1101/gad.553410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J. G., Majerciak V., Uldrick T. S., Wang X., Kruhlak M., Yarchoan R., Zheng Z. M. (2011). Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesviral IL-6 and human IL-6 open reading frames contain miRNA binding sites and are subject to cellular miRNA regulation. J. Pathol. 225, 378–389 10.1002/path.2962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J. G., Pripuzova N., Majerciak V., Kruhlak M., Le S. Y., Zheng Z. M. (2010). Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ORF57 promotes escape of viral and human interleukin-6 from microRNA-mediated suppression. J. Virol. 85, 2620–2630 10.1128/JVI.02144-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene J. D., Komisarow J. M., Friedersdorf M. B. (2006). RIP-Chip: the isolation and identification of mRNAs, microRNAs and protein components of ribonucleoprotein complexes from cell extracts. Nat. Protoc. 1, 302–307 10.1038/nprot.2006.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozomara A., Griffiths-Jones S. (2011). miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D152–D157 10.1093/nar/gkq1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krek A., Grun D., Poy M. N., Wolf R., Rosenberg L., Epstein E. J., Macmenamin P., Da Piedade I., Gunsalus K. C., Stoffel M., Rajewsky N. (2005). Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat. Genet. 37, 495–500 10.1038/ng1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagana A., Forte S., Russo F., Giugno R., Pulvirenti A., Ferro A. (2010). Prediction of human targets for viral-encoded microRNAs by thermodynamics and empirical constraints. J. RNAi Gene Silencing 6, 379–385 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos D., Pollara G., Henderson S., Gratrix F., Fabani M., Milne R. S., Gotch F., Boshoff C. (2010). miR-132 regulates antiviral innate immunity through suppression of the p300 transcriptional co-activator. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 513–519 10.1038/ncb2054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana M., Rauhut R., Lendeckel W., Tuschl T. (2001). Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science 294, 853–858 10.1126/science.1064921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau N. C., Lim L. P., Weinstein E. G., Bartel D. P. (2001). An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 294, 858–862 10.1126/science.1065062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. C., Ambros V. (2001). An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 294, 862–864 10.1126/science.1065329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. C., Feinbaum R. L., Ambros V. (1993). The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75, 843–854 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei X., Bai Z., Ye F., Xie J., Kim C. G., Huang Y., Gao S. J. (2010). Regulation of NF-kappaB inhibitor IkappaBalpha and viral replication by a KSHV microRNA. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 193–199 10.1038/ncb2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis B. P., Burge C. B., Bartel D. P. (2005). Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120, 15–20 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang D., Gao Y., Lin X., He Z., Zhao Q., Deng Q., Lan K. (2011). A human herpesvirus miRNA attenuates interferon signaling and contributes to maintenance of viral latency by targeting IKKepsilon. Cell Res. 21, 793–806 10.1038/cr.2011.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber D., Haas J. (2011). Viruses and microRNAs: a toolbox for systematic analysis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2, 787–801 10.1002/wrna.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Liang D., He Z., Deng Q., Robertson E. S., Lan K. (2011). miR-K12-7-5p encoded by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus stabilizes the latent state by targeting viral ORF50/RTA. PLoS ONE 6, e16224. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. T., Kincaid R. P., Arasappan D., Dowd S. E., Hunicke-Smith S. P., Sullivan C. S. (2010). Small RNA profiling reveals antisense transcription throughout the KSHV genome and novel small RNAs. RNA 16, 1540–1558 10.1261/rna.1779810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. T., Sullivan C. S. (2011). Expanding the role of Drosha to the regulation of viral gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 11229–11234 10.1073/pnas.1014026108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Sun R., Lin X., Liang D., Deng Q., Lan K. (2011). KSHV-encoded miR-K12-11 attenuates transforming growth factor beta signaling through suppression of SMAD5. J. Virol. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1128/JVI.01742-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C. C., Li Z., Chu C. Y., Feng J., Sun R., Rana T. M. (2010a). MicroRNAs encoded by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus regulate viral life cycle. EMBO Rep. 11, 784–790 10.1038/embor.2010.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F., Stedman W., Yousef M., Renne R., Lieberman P. M. (2010b). Epigenetic regulation of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency by virus-encoded microRNAs that target Rta and the cellular Rbl2-DNMT pathway. J. Virol. 84, 2697–2706 10.1128/JVI.01997-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F., Weidmer A., Liu C. G., Volinia S., Croce C. M., Lieberman P. M. (2008). Epstein-Barr virus-induced miR-155 attenuates NF-kappaB signaling and stabilizes latent virus persistence. J. Virol. 82, 10436–10443 10.1128/JVI.01613-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maragkakis M., Reczko M., Simossis V. A., Alexiou P., Papadopoulos G. L., Dalamagas T., Giannopoulos G., Goumas G., Koukis E., Kourtis K., Vergoulis T., Koziris N., Sellis T., Tsanakas P., Hatzigeorgiou A. G. (2009). DIANA-microT web server: elucidating microRNA functions through target prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W273–W276 10.1093/nar/gkp292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure L. V., Sullivan C. S. (2008). Kaposi’s sarcoma herpes virus taps into a host microRNA regulatory network. Cell Host Microbe 3, 1–3 10.1016/j.chom.2007.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesri E. A., Cesarman E., Boshoff C. (2010). Kaposi’s sarcoma and its associated herpesvirus. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 707–719 10.1038/nrc2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motsch N., Pfuhl T., Mrazek J., Barth S., Grasser F. A. (2007). Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) induces the expression of the cellular microRNA miR-146a. RNA Biol. 4, 131–137 10.4161/rna.4.3.5206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E., Vanicek J., Robins H., Shenk T., Levine A. J. (2008). Suppression of immediate-early viral gene expression by herpesvirus-coded microRNAs: implications for latency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 5453–5458 10.1073/pnas.0711910105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachmani D., Stern-Ginossar N., Sarid R., Mandelboim O. (2009). Diverse herpesvirus microRNAs target the stress-induced immune ligand MICB to escape recognition by natural killer cells. Cell Host Microbe 5, 376–385 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara A. J., Vahrson W., Dittmer D. P. (2008). Gene alteration and precursor and mature microRNA transcription changes contribute to the miRNA signature of primary effusion lymphoma. Blood 111, 2347–2353 10.1182/blood-2007-08-104463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara A. J., Wang L., Dezube B. J., Harrington W. J., Jr., Damania B., Dittmer D. P. (2009). Tumor suppressor micro RNAs are underrepresented in primary effusion lymphoma and Kaposi sarcoma. Blood 113, 5938–5941 10.1182/blood-2008-09-179168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce M., Matsumura S., Wilson A. C. (2005). Transcripts encoding K12, v-FLIP, v-cyclin, and the microRNA cluster of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus originate from a common promoter. J. Virol. 79, 14457–14464 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14457-14464.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer S., Sewer A., Lagos-Quintana M., Sheridan R., Sander C., Grasser F. A., Van Dyk L. F., Ho C. K., Shuman S., Chien M., Russo J. J., Ju J., Randall G., Lindenbach B. D., Rice C. M., Simon V., Ho D. D., Zavolan M., Tuschl T. (2005). Identification of microRNAs of the herpesvirus family. Nat. Methods 2, 269–276 10.1038/nmeth746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer S., Zavolan M., Grasser F. A., Chien M., Russo J. J., Ju J., John B., Enright A. J., Marks D., Sander C., Tuschl T. (2004). Identification of virus-encoded microRNAs. Science 304, 734–736 10.1126/science.1096781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punj V., Matta H., Schamus S., Tamewitz A., Anyang B., Chaudhary P. M. (2010). Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded viral FLICE inhibitory protein (vFLIP) K13 suppresses CXCR4 expression by upregulating miR-146a. Oncogene 29, 1835–1844 10.1038/onc.2009.460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z., Freitas E., Sullivan R., Mohan S., Bacelieri R., Branch D., Romano M., Kearney P., Oates J., Plaisance K., Renne R., Kaleeba J., Parsons C. (2010). Upregulation of xCT by KSHV-encoded microRNAs facilitates KSHV dissemination and persistence in an environment of oxidative stress. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000742. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z., Kearney P., Plaisance K., Parsons C. H. (2009). Pivotal advance: Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV)-encoded microRNA specifically induce IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by macrophages and monocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 87, 25–34 10.1189/jlb.0409251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samols M. A., Hu J., Skalsky R. L., Renne R. (2005). Cloning and identification of a microRNA cluster within the latency-associated region of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 79, 9301–9305 10.1128/JVI.79.14.9301-9305.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samols M. A., Skalsky R. L., Maldonado A. M., Riva A., Lopez M. C., Baker H. V., Renne R. (2007). Identification of cellular genes targeted by KSHV-encoded microRNAs. PLoS Pathog. 3, e65. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalsky R. L., Samols M. A., Plaisance K. B., Boss I. W., Riva A., Lopez M. C., Baker H. V., Renne R. (2007). Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes an ortholog of miR-155. J. Virol. 81, 12836–12845 10.1128/JVI.01804-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulier J., Grollet L., Oksenhendler E., Cacoub P., Cazals-Hatem D., Babinet P., D’agay M. F., Clauvel J. P., Raphael M., Degos L., Sigaux F. (1995). Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman’s disease. Blood 86, 1276–1280 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern-Ginossar N., Elefant N., Zimmermann A., Wolf D. G., Saleh N., Biton M., Horwitz E., Prokocimer Z., Prichard M., Hahn G., Goldman-Wohl D., Greenfield C., Yagel S., Hengel H., Altuvia Y., Margalit H., Mandelboim O. (2007). Host immune system gene targeting by a viral miRNA. Science 317, 376–381 10.1126/science.1140956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan C. S., Grundhoff A. T., Tevethia S., Pipas J. M., Ganem D. (2005). SV40-encoded microRNAs regulate viral gene expression and reduce susceptibility to cytotoxic T cells. Nature 435, 682–686 10.1038/nature03576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S., Patel A., Krause P. R. (2009). Novel less-abundant viral microRNAs encoded by herpes simplex virus 2 latency-associated transcript and their roles in regulating ICP34.5 and ICP0 mRNAs. J. Virol. 83, 1433–1442 10.1128/JVI.00259-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M., Boname J. M., Field S., Nejentsev S., Salio M., Cerundolo V., Wills M., Lehner P. J. (2008). Down-regulation of NKG2D and NKp80 ligands by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K5 protects against NK cell cytotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 1656–1661 10.1073/pnas.0707883105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai Y. H., Wu M. F., Wu Y. H., Chang S. J., Lin S. F., Sharp T. V., Wang H. W. (2009). The M type K15 protein of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus regulates microRNA expression via its SH2-binding motif to induce cell migration and invasion. J. Virol. 83, 622–632 10.1128/JVI.00869-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbach J. L., Cullen B. R. (2010). In-depth analysis of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus microRNA expression provides insights into the mammalian microRNA-processing machinery. J. Virol. 84, 695–703 10.1128/JVI.02013-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbach J. L., Kramer M. F., Jurak I., Karnowski H. W., Coen D. M., Cullen B. R. (2008). MicroRNAs expressed by herpes simplex virus 1 during latent infection regulate viral mRNAs. Nature 454, 780–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinther J., Hedegaard M. M., Gardner P. P., Andersen J. S., Arctander P. (2006). Identification of miRNA targets with stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, e107. 10.1093/nar/gkl590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. H., Hu T. F., Chen Y. C., Tsai Y. N., Tsai Y. H., Cheng C. C., Wang H. W. (2011). The manipulation of miRNA-gene regulatory networks by KSHV induces endothelial cell motility. Blood 118, 2896–2905 10.1182/blood-2011-01-330589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. S., Lai E. C. (2011). Alternative miRNA biogenesis pathways and the interpretation of core miRNA pathway mutants. Mol. Cell 43, 892–903 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Yao Y., Xu H., Lambeth L., Smith L. P., Kgosana L., Wang X., Nair V. (2009). A functional microRNA-155 ortholog encoded by the oncogenic Marek’s disease virus. J. Virol. 83, 489–492 10.1128/JVI.01346-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegelbauer J. M., Sullivan C. S., Ganem D. (2009). Tandem array-based expression screens identify host mRNA targets of virus-encoded microRNAs. Nat. Genet. 41, 130–134 10.1038/ng.266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]