Abstract

APE1 (Ref-1) is an essential human protein involved in DNA damage repair and regulation of transcription. Although the cellular functions and biochemical properties of APE1 are well characterized, the mechanism involved in regulation of the cellular levels of this important DNA repair/transcriptional regulation enzyme, remains poorly understood. Using an in vitro ubiquitylation assay, we have now purified the human E3 ubiquitin ligase UBR3 as a major activity that polyubiquitylates APE1 at multiple lysine residues clustered on the N-terminal tail. We further show that a knockout of the Ubr3 gene in mouse embryonic fibroblasts leads to an up-regulation of the cellular levels of APE1 protein and subsequent genomic instability. These data propose an important role for UBR3 in the control of the steady state levels of APE1 and consequently error free DNA repair.

INTRODUCTION

Genome instability is the major cause of many human diseases, including cancer. One of the major sources of genome instability is the loss of a DNA base due to hydrolytic attack of the glycosylic bond linking DNA bases to the sugar phosphate backbone of the DNA molecule (1). These abasic sites (apurinic/apyrimidinic, AP sites) in DNA can also arise as an intermediate product during excision repair of various DNA base lesions. It has been estimated that every single human cell repairs about 10 000 AP sites per day (2) and this highlights the importance of the proteins involved in the repair of this cytotoxic and mutagenic lesion. Human AP endonuclease-1 (APE1, also known as Ref-1) initiates repair of AP sites by incising the phosphodiester bond 5′ to the AP site and generating a DNA single-strand break (SSB) containing a 5′-sugar phosphate residue (3,4). This SSB is further repaired by DNA polymerase β and XRCC1–DNA ligase IIIα complex. DNA polymerase β removes the 5′-sugar phosphate residue and adds one undamaged nucleotide into the repair gap. Finally, XRCC1–DNA ligase IIIα complex seals the DNA ends thus accomplishing the repair process (5). Although being a small protein (36 kDa), APE1 has multiple other enzymatic activities, including 3′-phosphatase, 3′-phosphodiesterase and 3′- to 5′-exonuclease activities specific for internal nicks and gaps in DNA (6). It has also been shown to catalyse the release of 3′-phosphoglycolate moieties that block the repair of DNA SSBs (7–10). All these enzymatic activities of APE1 are important for the repair of DNA lesions induced by oxidative stress and ionising radiation. In addition, APE1 has an important role as a reductive activator of a number of transcription factors, including p53, AP-1, NF-кB and HIF-1α, in response to oxidative stress (11).

APE1 is known to be absolutely required for cellular survival since deletion of APE1 in mice is embryonic lethal (12–14) and stable cell lines lacking the protein have not been established, again pointing to a critical role for APE1. Down-regulation of APE1 by RNA interference (15,16) and the generation of conditional Ape1 null mice (16) confirmed that AP endonuclease activity is essential for mammalian cell viability and plays a central role in endogenous and induced DNA damage processing. Consequently, controlling the cellular levels of APE1 protein is very important as both over- or under-expression of APE1 leads to genomic instability (17–19) and is frequently found in cancer cells (11,20–23) and neurological disorders [(24) and references within].

We have previously demonstrated that the cellular amounts of DNA polymerase β and XRCC1–DNA ligase IIIα, involved in repair of SSBs generated by APE1, are tuned to the amount of DNA damage through regulated proteasomal degradation. This is controlled by the E3 ubiquitin ligases Mule, CHIP and the DNA damage signalling protein and tumour suppressor ARF (25,26). However the mechanism controlling APE1 levels is unknown. Assuming that APE1 levels are also controlled by ubiquitylation, we first demonstrated the existence of ubiquitylated APE1 in human cells and then developed an in vitro ubiquitylation assay for APE1. Using this assay, we purified UBR3 as the major human E3 ubiquitin ligase targeting APE1 for ubiquitylation, and demonstrate that UBR3 controls the cellular levels of APE1 and is required for genome stability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies

Polyclonal APE1 antibodies were purified as described (27). APE1 mouse monoclonal antibodies for identification of mouse APE1 (APEX) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). ARF and 53BP1 antibodies were purchased from Bethyl Laboratories (Montgomery, USA), tubulin antibodies were from Sigma-Aldrich (Gillingham, UK), Mdm2 antibodies were from Santa Cruz (California, USA) and γ-H2AX antibodies were from Millipore (Watford, UK). Actin, hsp70 and ubiquitin antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). UBR3 antibodies were purified as recently described (28).

Plasmids and proteins

Ubiquitin, E1 and E2 enzymes were purchased from Boston Biochemicals (Cambridge, USA). pET14b plasmid encoding human APE1 protein was kindly provided by Prof. Hickson and APE1 mutants were constructed using the ‘QuikChange’ protocol (Stratagene, Amsterdam, Holland) and confirmed by sequencing. Human histidine-tagged APE1 was purified by HisTrap HP column chromatography (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). Plasmid encoding mouse APE1 protein (APEX) was kindly provided by Dr Nakabeppu and the Apex gene was re-cloned into pCMV3Tag3a plasmid (Agilent Technologies, Stockport, UK). N-terminal FLAG-tagged mouse UBR3 (UBR3) was expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae SC295 (MATa, GAL4 GAL80 ura3-52, leu2-3,112 reg1-501 gal1 pep4-3) from the PADH1 promoter in a high copy vector as described previously (28). To purify UBR3 protein, the yeast lysate containing UBR3 was mixed with anti-Flag M2 agarose beads (Sigma, Gillingham, UK) and after washing the beads, the bound UBR3 protein was eluted using FLAG peptide-containing elution buffer (200 µg/ml). Purified UBR3 protein was dialyzed against PBS, concentrated and stored at −80°C until required.

Establishment and immortalization of Ubr3−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts

Construction and characterization of Ubr3−/− mouse was recently described (28). Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were established from wild-type and Ubr3−/− embryos at E13.5 in the 129SvImJ/C57BL/6 background as previously described (29). Immortalized MEFs were established from primary MEFs by repeated cell cultures over ∼2 months (∼1.5 × 106 cells onto a 10 cm2 plate every 3–5 days).

Whole-cell extracts

Whole-cell extracts were prepared by Tanaka's method (30). Briefly, cells were resuspended in one packed cell volume of buffer containing 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.8), 200 mM KCl, 1 μg/ml of each protease inhibitor (pepstatin, aprotinin, chymostatin and leupeptin), 1 mM DTT and 1 mM PMSF. Two packed cell volumes of buffer containing 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.8), 600 mM KCl, 40% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA and 0.2% Nonidet P-40 was then added and mixed thoroughly before rocking the cell suspension for 2 h at 4°C. The cell lysate was then centrifuged at 40 000 rpm at 4°C for 20 min and the supernatant was collected, aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

Cell fractionation

Cell fractionation was performed as recently described (31). Briefly, cell pellets were resuspended in two packed cell volumes of buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT and 1 μg/ml each of aprotinin, pepstatin, chymostatin and leupeptin, and incubated on ice for 10 min. Following centrifugation at 10 000 rpm for 2 min, the supernatant containing cytoplasmic proteins (C) was collected. The nuclear pellet was similarly extracted with two packed cell volumes of buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.5 M KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.75% (v/v) Triton X-100, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT and 1 μg/ml each of aprotinin, pepstatin, chymostatin and leupeptin and the supernatant containing nuclear proteins (N) was collected. For identification of ubiquitylated APE1 bands from HeLa cells, 1 mM NEM was also added to each of the buffers prior to extractions.

Western blots

Western blots were performed by standard procedure as recommended by the vendor (Novex, San Diego, USA). Blots were visualized using the Odyssey image analysis system (Li-cor Biosciences, Cambridge, UK).

In vitro ubiquitylation assay

In vitro ubiquitylation was performed as recently described (25). Briefly, assays were performed in a 15 µl reaction volume in the presence of E1 activating enzyme (0.7 pmol), the indicated E2 conjugating enzymes (9.5 pmol) and ubiquitin (0.6 pmol) or mutant ubiquitin unable to form polyubiquitin chains (Boston Biochem, Cambridge, USA) in buffer containing 25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 4 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, 200 µM CaCl2, 1 mM DTT, 10 µM MG-132 for 1 h at 30°C. SDS–PAGE sample buffer 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2.5 % beta-mercaptoethanol, 1 % SDS, 5 % glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 0.15 mg/ml bromophenol blue) was added, the samples were heated for 5 min at 95°C prior to separation of the proteins on a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, followed by transfer to a PVDF membrane and immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies.

Partial purification of monoubiquitylated APE1

Whole-cell extracts from 20 g HeLa cells was prepared as described above and dialysed against Buffer A (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF) containing 150 mM KCl and 1 mM NEM. The dialysate was clarified by centrifugation at 25 000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C, filtered through 0.45 -µm filters and fractionated by Phosphocellulose chromatography using Buffer A containing 150 mM KCl and 1 mM NEM. Proteins were eluted using Buffer A containing 1 M KCl and 1 mM NEM, concentrated and diluted to 50 mM KCl and fractionated by Mono-Q chromatography and the flow-through was collected. Proteins were then fractionated by Mono-S chromatography using Buffer A containing 50 mM KCl and proteins eluted using a linear gradient of 50–1000 mM KCl. Fractions were analysed by 10% SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting with APE1 or ubiquitin antibodies.

Mapping and identification of ubiquitylation sites

Cleavage of the first 35 amino acids from the APE1 protein for in vitro ubiquitylation assays was achieved by treating APE1 (8 µg) with 0.5 µg of trypsin in buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2 and 1 M urea for 2 h at 23°C. APE1 was then buffer exchanged three times using Amicon Ultra-4 filter units (Millipore, Watford, UK) to remove trypsin and the N-terminal tail of APE1, prior to incubation in the in vitro ubiquitylation assay. For identification of ubiquitylation sites, full-length APE1 protein was ubiquitylated in vitro using UbcH2 E2 conjugating enzyme as described above, separated by SDS–PAGE and the Coomassie stained band corresponding to monoubiquitylated APE1 was excised, digested with trypsin and analysed by tandem mass spectrometry as recently described (26).

Purification of the E3 ubiquitin ligase for APE1

Cytoplasmic proteins were isolated from 20 g HeLa cells (Cilbiotech, Mons, Belgium) as described above and dialysed against Buffer A (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF) containing 150 mM KCl. The dialysate was clarified by centrifugation at 25 000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C, filtered through 0.45 -µm filters and applied to a Phosphocellulose column using Buffer A containing 150 mM KCl and the flow-through was collected (PC-FI). PC-FI was concentrated using Vivaflow 50 and 10 kDa MWCO PES membrane modules (Sartorius Stedim, Surrey, UK), diluted 2-fold to achieve a final concentration of 75-mM KCl in the fraction and then added to a 20 ml HiLoad Mono-Q Sepharose column (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK), washed with Buffer A containing 50 mM KCl and proteins eluted using a linear gradient from 50 to 1000 mM KCl. Active fractions were pooled, concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 filter units (Millipore, Watford, UK) and loaded onto a Superose-12 column (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) in Buffer A containing 150 mM KCl. Active fractions were pooled, diluted to 50 mM KCl and loaded onto a 1 ml Mono Q HR 5/5 column (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) in buffer A containing 50 mM KCl. Proteins were eluted using a linear gradient of 50–1000 mM KCl. At each chromatography stage, aliquots of the fractions were analysed for E3 ubiquitin ligase activity using APE1 as a substrate and active fractions pooled for the next chromatography step. Active fractions from the final Mono-Q chromatography stage were analysed by tandem mass spectrometry to identify candidate E3 ubiquitin ligases, as recently described (26).

Plasmid transfection

Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

RT–PCR analysis

RNA was prepared from Ubr3 wild-type and knockout MEFs using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK) and cDNA was subsequently generated using the SuperScript RT–PCR system (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). UBR3, APE1 and actin was amplified using the following primers: 5′-GGGAATATTTGAACTTGATTTAATCTG-3′ and 5′-CCACACTGGACACGACTTCA-3′; 5′-CGGGGAAGAACCCAAGTC-3′ and 5′-TCCTTCTCGGTTTTCTTTGC-3′; 5′-GGAGGGGGTTGAGGTGTT-3′ and 5′-TGTGCACTTTTATTGGTCTCAAG-3′, respectively. Cycling conditions of one cycle at 95°C for 5 min, 25 cycles (or 30 cycles for UBR3) at 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 20 s and 72°C for 20 s, and one cycle at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were separated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis containing SYBR Green (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and analysed using the Molecular Imager FX system (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, UK).

Clonogenic survival assay

Ubr3 wild-type and knockout MEFs were seeded in triplicate onto 10-cm2 dishes at a density of 300 cells/plate and allowed to adhere for 16 h. The cells were then treated with methyl methanesulphonate (MMS; Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham, UK) for 45 min, the cells were washed twice with PBS, the media replaced and the cells allowed to form colonies over 7 days. Colonies were stained using methylene blue and subsequently counted. The surviving fraction was calculated by normalizing against the colony numbers achieved for the untreated dishes.

Immunostaining

Subconfluent cell monolayers on coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, the cells were permeabilized with 0.2% (w/v) Triton X-100 for 10 min at 4°C and blocked at room temperature with 2% (w/v) BSA—Fraction V for 1 h. The coverslips were then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies raised against APE1 or 53BP1 diluted 1:300 in BSA. The coverslips were washed and incubated in secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 488 F(ab′)2 fragment of goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) for 1 h. Slides were then mounted using Vectashield hard set mounting media containing 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) and imaged using the BioRad MRC 600 confocal microscope and 488 nm (FITC) argon laser lines for excitation.

RESULTS

APE1 ubiquitylation in living cells

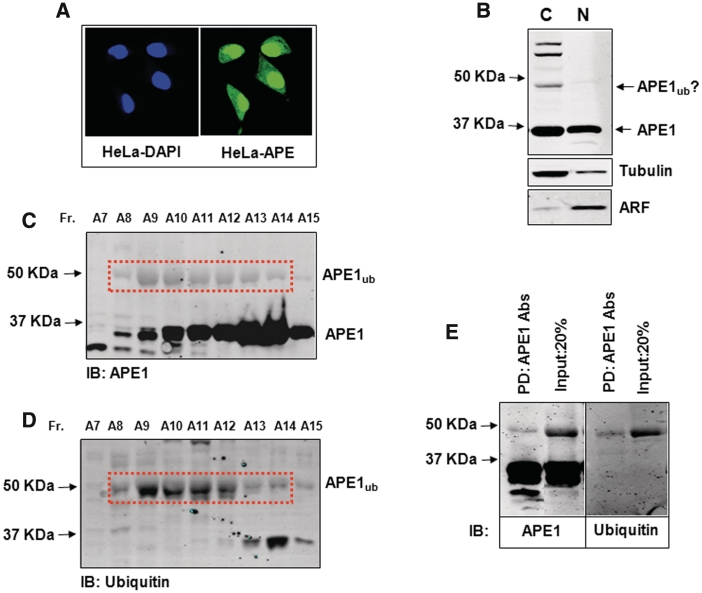

In HeLa cells, the concentration of APE1 protein is much higher in the nucleus, although a substantial amount can also be detected in the cytoplasm (Figure 1A). Taking into account that the volume of the cytoplasm is ∼8-fold larger than the volume of the nucleus, the absolute amount of APE1 that can be extracted into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions is approximately the same (Figure 1B). To demonstrate that APE1 ubiquitylation occurs in living cells, we performed cell fractionation in the presence of N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), which is an effective inhibitor of deubiquitylation enzymes. We found that in HeLa cell extracts prepared with NEM, in addition to APE itself, immunoblotting with APE1-specific antibodies detected at least three extra protein bands with a molecular weight of between 45 and 60 kDa, but these were only observed in the cytoplasmic fraction (Figure 1B). Since the molecular weight of monoubiquitylated APE1 is expected to be ∼44 kDa, the protein with a molecular weight just <50 kDa that cross-reacted with the APE1 antibodies was considered as a potential candidate for monoubiquitylated APE1 (APE1ub, Figure 1B, indicated by arrow). To provide evidence that this protein was APE1ub, we partially purified this protein from a cytoplasmic extract of HeLa cells by sequential Phosphocellulose, Mono-Q and Mono-S chromatographies and monitored fractions with APE1 antibodies. Fractions containing the ∼44–50 KDa protein cross-reacting with the APE1 antibodies were then probed with antibodies directed against ubiquitin. We found that fractions containing the ∼44–50 kDa protein cross-reacted with both APE1 (Figure 1C) and ubiquitin (Figure 1D) specific antibodies. Furthermore, after precipitation of this protein with APE1 antibodies, the precipitated protein still cross-reacted with both APE1 and ubiquitin antibodies (Figure 1E). We thus conclude that this ∼44-kDa protein is monoubiquitylated APE1.

Figure 1.

Purification of ubiquitylated APE1 from human cells. (A) HeLa cells were fixed and immunostained with DAPI and APE1 antibodies demonstrating cytoplasmic and nuclear localization of APE1. (B) Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions prepared from HeLa cells were analysed by 10% SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. Three bands cross-reacting with APE1 antibodies, in addition to the 36 kDa native form of APE1, were present in the cytoplasmic fraction and were predicted to be ubiquitylated APE1. (C and D) Analysis of Mono-S chromatography fractions purified from HeLa cells analysed by 10% SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting using either (C) APE1 or (D) ubiquitin antibodies. (E) The peak monoubiquitylated APE1 containing Mono-S fraction (A9) was immunodepleted using APE1 antibodies and the pull-down was then analysed by 10% SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting using either APE1 (left panel) or ubiquitin (right panel) antibodies. Molecular weight markers are indicated on the left hand side of appropriate figures and the positions of monoubiquitylated APE1 (APE1ub) are shown.

UBR3 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase for APE1

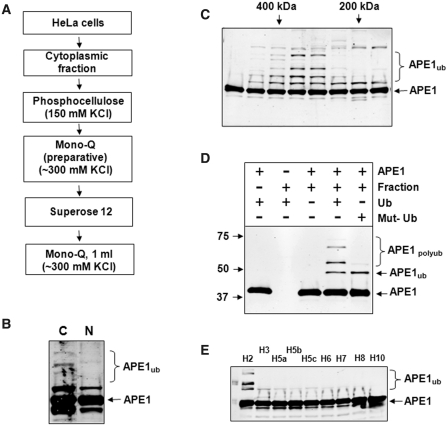

Having established that APE1 ubiquitylation occurs in living cells, we pursued purification of an E3 ubiquitin ligase activity for APE1 from human cell extracts using a series of chromatography columns (Figure 2A) and an in vitro ubiquitylation assay. We first observed that the majority of APE1 E3 ubiquitin ligase activity was detected in the cytoplasm (Figure 2B) and that the activity became very pronounced after gel-filtration over a Superose 12 column (Figure 2C). From this column, we determined that the E3 ubiquitin ligase for APE1 was ∼200–400 kDa. We further demonstrated that in vitro ubiquitylation of recombinant APE1 is dependent on the presence of both active fraction and ubiquitin (Figure 2D, fourth lane) and further established, using wild-type and mutant ubiquitin unable to form polyubiquitin chains, that recombinant APE1 is polyubiquitylated since we observed only a single product of ubiquitylation using mutant ubiquitin (Figure 2D, last lane). We also screened nine ubiquitin E2 conjugating enzymes for their ability to mediate ubiquitylation of APE1 and discovered that the ubiquitylation reaction is specific for UbcH2 (human homologue of yeast Ubc8, Figure 2E). Proteins from active fractions from the final purification step (Mono-Q column) were subjected to nanoLC–MS/MS tandem mass spectrometry, which revealed UBR3 as a potential E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in UbcH2-dependent APE1 ubiquitylation (Supplementary Figure S1). Indeed, when active fractions were tested for the presence of UBR3, we found a strong correlation between APE1 ubiquitylation activity in these active fractions (Figure 3A, upper panel) and the amount of UBR3 protein detected by immunoblotting (Figure 3A, lower panel). To confirm that UBR3 is responsible for APE1 ubiquitylation in the Mono-Q fractions, we immunoprecipitated UBR3 away from active fractions (Figure 3B, lower panel) and demonstrated that UBR3-depleted fractions had significantly reduced ubiquitylation activity (Figure 3B, upper panel). We next purified recombinant mouse UBR3 protein (Figure 3C) and found that it was able to polyubiquitylate APE1 in an in vitro ubiquitylation system reconstituted with purified enzymes (Figure 3D).

Figure 2.

Purification of the E3 ubiquitin ligase for APE1. (A) Purification scheme for the isolation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase for APE1 from HeLa cells. (B) Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions (8 µg) were prepared from HeLa cells and analysed for in vitro ubiquitylation activity for APE1 (2.8 pmol) in the presence of E1 (0.7 pmol), ubiquitin (0.6 nmol) and various E2 enzymes (9.5 pmol). Reactions were separated by 10% SDS–PAGE and analysed by immunoblotting using APE1 antibodies. The major ubiquitylation activity against APE1 can be observed in the cytoplasmic fraction. (C) In vitro ubiquitylation of APE1 (2.8 pmol) by Superose 12 fractions purified from HeLa cells in the presence of E1 (0.7 pmol), ubiquitin (0.6 nmol) and various E2 enzymes (9.5 pmol). Reactions were separated by 10% SDS–PAGE and analysed by immunoblotting using APE1 antibodies. E3 ubiquitin ligase activity for APE1 corresponds to a protein of molecular weight between 200 and 400 kDa. (D) In vitro ubiquitylation of APE1 (2.8 pmol) by an active fraction purified from HeLa cells in the presence of E1 (0.7 pmol), various E2 enzymes (9.5 pmol) and ubiquitin (Ub; 0.6 nmol) or mutant ubiquitin (Mut-Ub) unable to form polyubiquitin chains. (E) In vitro ubiquitylation of APE1 (2.8 pmol) by an active fraction purified from HeLa cells in the presence of E1 (0.7 pmol), ubiquitin (Ub; 0.6 nmol) and various E2 enzymes (9.5 pmol each). Reactions (D and E) were separated by 10% SDS–PAGE and analysed by immunoblotting using APE1 antibodies. Molecular weight markers are indicated on the left hand side of appropriate figures and the positions of ubiquitylated APE1 (APE1ub) are shown.

Figure 3.

UBR3 is the E3 ubiquitin ligase for APE1. (A) In vitro ubiquitylation of APE1 (2.8 pmol) by the final Mono-Q chromatography fractions purified from HeLa cells in the presence of E1 (0.7 pmol), UbcH2 (10.5 pmol) and ubiquitin (0.6 nmol) were analysed by 10% SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting using APE1 antibodies. Fractions containing APE1 ubiquitylation activity were shown to correlate with the presence of UBR3 protein detected by immunoblotting (lower panel). (B) The peak APE1 ubiquitylation activity containing fraction from the final Mono-Q chromatography was mock immunodepleted and immunodepleted with UBR3 antibodies. The fraction was subsequently analysed for in vitro ubiquitylation of APE1 (2.8 pmol) in the presence of E1 (0.7 pmol), UbcH2 (10.5 pmol) and ubiquitin (0.6 nmol) by 10% SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting using APE1 antibodies (upper panel). Furthermore, the pull-down was analysed by 10% SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting using UBR3 antibodies (lower panel). (C) N-terminal Flag-tagged mouse UBR3 was expressed in S. cerevisiae, purified and analysed by 4–12% SDS–PAGE and Coomassie staining. (D) Purified Flag-tagged mouse UBR3 was analysed for in vitro ubiquitylation of APE1 (2.8 pmol) in the presence of E1 (0.7 pmol), UbcH2 (10.5 pmol) and ubiquitin (0.6 nmol) by 10% SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting using APE1 antibodies and UBR3 antibodies (lower panel). Molecular weight markers are indicated on the left hand side of appropriate figures and the positions of ubiquitylated APE1 (APE1ub) are shown.

It has recently been reported that Mdm2 is involved in APE1 ubiquitylation (33). Although we found that recombinant Mdm2 is able to ubiquitylate APE1 in an in vitro ubiquitylation assay (Supplementary Figure S2), we discovered that the major ubiquitylation activity for APE1 purified from HeLa cells did not co-purify with Mdm2 protein (Supplementary Figure S3). We thus conclude that UBR3 is the major human E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in polyubiquitylation of APE1.

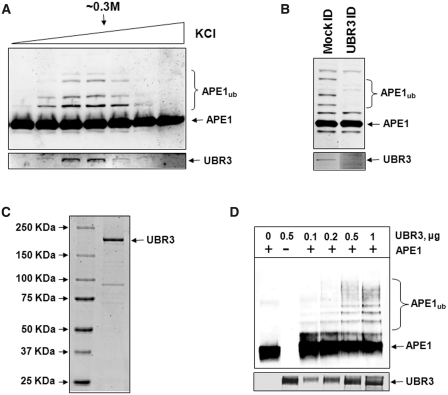

UBR3 ubiquitylates several lysines at the N-terminus of APE1

APE1 protein contains nine lysines within the 35 amino acid N-terminal region (Figure 4A). To test whether these residues are the sites of ubiquitylation, we cleaved off this N-terminal region by controlled trypsin hydrolysis. We demonstrated that in contrast to the full length protein (∼32% of the substrate is ubiquitylated), truncated APE1 lacking the first 35 amino acids from the N-terminus cannot be efficiently ubiquitylated by a UBR3-containing fraction purified from HeLa cells (∼4% of the substrate is ubiquitylated, Figure 4B). In support of this finding, nanoLC–MS/MS tandem mass spectrometry of in vitro ubiquitylated full length APE1 identified lysines 7, 24, 25, 27, 32 and 35 as targets for ubiquitylation. At least for an in vitro reaction, it seems that these lysines are interchangeable ubiquitylation targets for UBR3, since replacement of individual lysines or combinations of two to three lysines with arginines did not significantly reduce ubiquitylation (Figure 4C). The ubiquitylation of APE1 by UBR3 only significantly dropped when the majority of lysines (K24, K25, K27, K31, K32 and K35) were replaced with arginines and was completely abolished in the Lysine Less Mutant (LLM), that was constructed by replacement of all but K3 within the first 35 amino acids of APE1 (Figure 4C, last lane).

Figure 4.

Identification of UBR3 ubiquitylation sites within APE1. (A) Schematic diagram of the protein structure of APE1 showing the nuclear localization sequences (NL1 and NL2), Ref-1 domain and nuclease domain. Major sites (K7/K24/K25/K27/K32/K35) of ubiquitylation by UBR3 identified by mass spectrometry are shown. (B) An N-terminal truncation of APE1 lacking the first 35 amino acids (APE1Δ1-35) was analysed for in vitro ubiquitylation, in comparison to full length protein (FL), by an active fraction purified from HeLa cells in the presence of E1 (0.7 pmol), UbcH2 (10.5 pmol) and ubiquitin (0.6 nmol) by 10% SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting using APE1 antibodies. (C) Wild-type protein (WT) and APE1 mutants, in which the indicated lysines were mutated to arginines, were analysed for in vitro ubiquitylation by an active fraction purified from HeLa cells in the presence of E1 (0.7 pmol), UbcH2 (10.5 pmol) and ubiquitin (0.6 nmol) by 10% SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting using APE1 antibodies.

UBR3 knockout cells have increased levels of APE1 and show genome instability

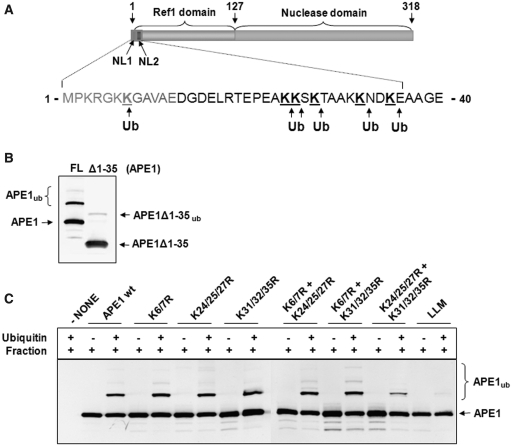

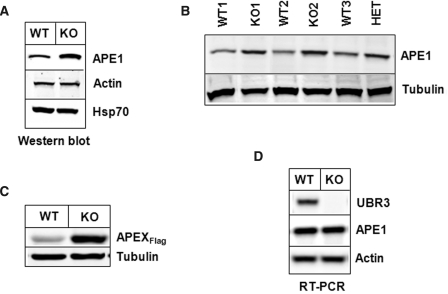

Ubr3-knockout mice have been generated and have previously been shown to have a genetic background-dependent lethality, indicating an essential role for this gene (28). To assess the role of UBR3 in controlling APE1 levels, we prepared cell extracts from wild-type and Ubr3-knockout MEFs and found ∼2-fold increase in APE1 levels in Ubr3-knockout cells (Figure 5A). To exclude that the increase in APE1 levels was due to clonal variability, we further analysed two more independent Ubr3-knockout cell lines in comparison to three independent wild-type cell lines and found that the Ubr3-knockout cells always contained higher APE1 levels (Figure 5B). Interestingly, a cell line generated from a Ubr3-heterozygous mouse also contained higher protein levels of APE1 (Figure 5B). To further demonstrate that APE1 stability depends on UBR3, we transfected plasmids expressing mouse AP-endonuclease 1 (APEX) into wild-type or Ubr3-knockout cells. The level of APEX expression was ∼5-fold higher in Ubr3-knockout cells compared to wild-type cells (Figure 5C). RT–PCR of the RNA purified from Ubr3-knockout cells clearly indicated that the levels of ape1 mRNA in Ubr3-wild-type and Ubr3-knockout cells is approximately the same (Figure 5D) and shows that modulation of APE1 is at the protein level. These data were further confirmed using real-time PCR that showed only a 1.3 ± 0.1-fold increase in ape1 mRNA levels in Ubr3-knockout cells, in contrast to an at least 2-fold increase in protein level (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 5.

Cells from Ubr3-knockout mice contain elevated levels of APE1 protein. (A and B) Whole cell extracts from MEFs from several wild-type (WT), Ubr3-knockout (KO) and heterozygous mice (HET) were prepared and analysed by 10% SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies (C) Wild-type and Ubr3-knockout MEFs cells were grown on 10-cm2 dishes for 24 h to 70–80% confluency and then transfected with equal amounts of mouse Flag-tagged APE1 (APEXFlag) expression plasmid. After 24 h, cells were pelleted by centrifugation, whole cell extracts were prepared and analysed by 10% SDS–PAGE and western blotting with the antibodies indicated. (D) RNA was prepared from wild-type and Ubr3-knockout MEFs and the levels of APE1, UBR3 and actin mRNA analysed by RT–PCR.

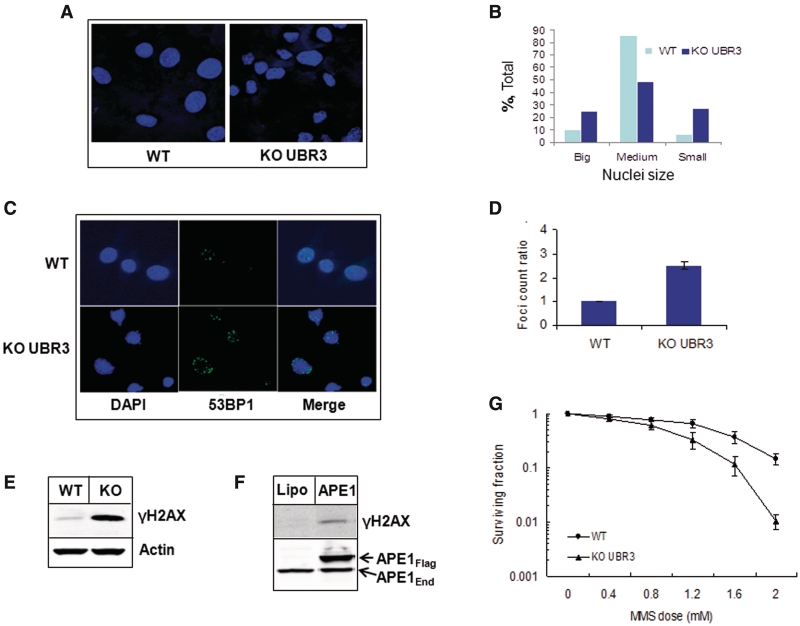

We also noticed that the nuclei of Ubr3-knockout cells have significant variations in size and shape, in comparison to wild-type cells, that is an indicator of genetically unstable cells (Figure 6A and B), (33). We hypothesized that elevated levels of APE1 in Ubr3-knockout cells leads to genomic instability through the imbalance of DNA repair and the generation of excessive SSBs that in turn will be converted into DNA double-strand breaks during replication. In support of this hypothesis, we observed a higher number of spontaneously formed 53BP1 foci (Figure 6C and D), as well as higher levels of histone H2AX phosphorylation in Ubr3-knockout cells compared to wild-type cells (Figure 6E), indicating increased levels of endogenously generated DNA double-strand breaks. If our model is correct, then over-expression of APE1 itself should generate DNA strand breaks by misbalancing the repair of endogenous DNA lesions. Indeed, over-expression of APE1 in HeLa cells induced formation of DNA double-strand breaks as detected by increased phosphorylation of histone H2AX (Figure 6F). Imbalance of DNA repair in Ubr3-knockout cells should also lead to increased formation of DNA strand breaks after mutagen treatment and these can then increase cell toxicity. Indeed, using clonogenic survival assays we were able to show that Ubr3 knockout cells, in contrast to the wild-type cells, are more susceptible to the cell killing effects of the DNA alkylating agent MMS (Figure 6G), that generates base lesions that are almost entirely dependent on APE1 for their repair.

Figure 6.

Cells from Ubr3-knockout mice are genetically instable. (A and C) MEFs from wild-type and Ubr3-knockout mice were fixed and immunostained with the indicated antibodies and stained with DAPI. (B) Graphic presentation of nuclei size distribution in wild-type and Ubr3-knockout fibroblasts (500 cell nuclei were evaluated). (D) Graphic representation of 53BP1 foci ratios calculated from three individual slides (53BP1 foci were counted from 100 cells/slide). (E) Whole-cell extracts from MEFs from wild-type (WT) and Ubr3-knockout (KO) mice were prepared and analysed by 10% SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. (F) HeLa cells were grown on 10-cm2 dishes for 24 h to 70–80% confluency and then transfected with human Flag-tagged APE1 (APE1Flag) expression plasmid. After 24 h cells were pelleted by centrifugation, whole cell extracts were prepared and analysed by 10% SDS–PAGE and western blotting with the antibodies indicated. (G) MEFs from wild-type and Ubr3-knockout mice were grown on 10-cm2 dishes in triplicate and treated with the indicated concentrations of MMS for 45 min and colonies allowed to grow for 7 days. The graph represents the mean surviving fraction normalized against the untreated controls from three independent experiments and the standard errors are shown.

DISCUSSION

APE1 is an essential protein that possesses multiple activities involved in DNA repair and it also operates as a redox factor activating a number of transcription factors, including NF-κB, AP-1 and p53 (34). Several studies have addressed the transcriptional regulation of APE1 however, it is also clear that post-translational modifications of APE1 play a major role in protein activity, stability and localization, although very little is known about the mechanisms involved [reviewed in (35)].

In this study, we investigated the role of ubiquitylation in the regulation of the steady state levels of APE1 protein and identify both the E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme, UbcH2 and the E3 ubiquitin ligase, UBR3, as the major enzymes involved. Previously, it was suggested that ubiquitylation of APE1 is accomplished by Mdm2 (32). However, even though we found that Mdm2 can ubiquitylate APE1 in vitro, we were not able to demonstrate that Mdm2 purified from human cell extracts possessed a significant ubiquitylation activity for APE1. Nevertheless, we cannot completely rule out that Mdm2 may serve as a minor backup E3 ubiquitin ligase for APE1 in the absence of UBR3. There is also a possibility that Mdm2, as a major regulator of p53, is involved in transcriptional regulation of APE1 since p53 was implicated in the negative regulation of APE1 transcription (36).

We have previously identified the mouse Ubr3 gene as one of the ubiquitin ligase family members characterized by the UBR box (28,29). The UBR box is a signature unique to all known recognition E3 components (UBR1, UBR2, UBR4 and UBR5) of the mammalian N-end rule pathway, called N-recognins [reviewed in (37)]. The UBR box of mouse UBR1 and UBR2 has been shown to function as a substrate recognition domain required for type-1 (basic; Arg, Lys and His) and type-2 (bulky hydrophobic; Phe, Tyr, Trp, Leu and Ile) destabilizing N-terminal residues of the N-end rule pathway (29,38). Although UBR3 shares several domains and sequence similarities with UBR1 (25% identity, 51% similarity) and UBR2 (25% identity, 48% similarity), UBR3 apparently does not exhibit N-recognin activities, suggesting that UBR3 may have a function outside the conventional N-end rule pathway. However, very little is known about its substrates and cellular functions. We now demonstrate that UBR3 is involved in regulation of the steady state levels of APE1 protein by ubiquitylating its N-terminal lysines, thus stimulating its proteasomal degradation. Since APE1 has the N-terminal Met-Pro-Lys sequence and there is no evidence that APE1 is cleaved into a C-terminal fragment bearing a destabilizing N-terminal residue, it appears that UBR3 recognizes APE1 through an alternative degradation signal.

In our studies to demonstrate the effect of ubiquitylation on APE1, we used MEFs generated from mice lacking exon 1 of Ubr3 and show that a loss of Ubr3 results in an increased level of APE1. We also show that there is no increase in ape1 mRNA levels suggesting that this difference in APE1 protein level is due to post-translational regulation. It is still unclear whether accumulation of APE1 in Ubr3 knockout fibroblasts is due to a lack of mono- or polyubiquitylation, although based on the in vitro ubiquitylation data the latter seems more probable and since due to the very high stability of APE1 protein (turnover time >16 h) neither cycloheximide nor MG132 treatment experiments can be performed. In spite of many attempts, we were also unable to transiently over-express or efficiently knockdown UBR3 in mammalian cells. Although the mechanism preventing UBR3 over-expression is unclear, most probably an excess of UBR3 causes cell toxicity.

While common sense suggests that over-expression of APE1 should result in faster DNA repair, recent data from several laboratories indicates that an uncoordinated increase in one of the repair enzymes of the base excision repair (BER) pathway leads to misbalanced DNA repair and genome instability (39). In the case of excessive APE1, the repair intermediate that would accumulate would be DNA SSBs that arise during BER of damaged DNA bases or direct incision of abasic sites (5). If the amount of SSBs generated by APE1 exceed the repair capacity of the subsequent steps of BER (gap filling by DNA polymerase β and DNA ligation by XRCC1–DNA ligase IIIα complex), these SSBs can then be converted into DNA double-strand breaks during replication. Accumulation of DNA double-strand breaks may result in genomic instability and increased susceptibility to the cell killing effects of DNA damaging agents. The extent to which these events occur would of course be dependent on the cell type affected, since up-regulated downstream BER activity may compensate for the effects of APE1 over-expression and the ultimate effect on cellular survival is furthermore dependent on the double-strand break repair capacity of the affected cell. For the Ubr3-knockout cells, which contain higher protein levels of APE1 than the corresponding wild-type cells, we observed the hypothesized effects. First, we found that Ubr3-knockout cells exhibit a significant variation in the size and shape of the nucleus, that is a well-known hallmark of genomic instability (33). We next demonstrated that Ubr3-knockout cells had a higher number of spontaneous 53BP1 foci and increased levels of γH2AX in response to endogenously generated damage, both indicators for the presence of DNA double-strand breaks (40). We show that this increase is likely due to APE1 over-expression since transient over-expression of APE1 in HeLa cells also show an increase in the levels of γH2AX. Finally, we demonstrate that Ubr3-knockout cells are more susceptible to the cell killing effects of the DNA alkylating agent MMS, that generates base damages which are almost entirely dependent on APE1 for their repair.

It appears that precise tuning of the levels of DNA repair enzymes involved in the BER pathway is required for genome stability. Even a moderate misbalance of the equilibrium between BER proteins may lead to accumulation of DNA double-strand breaks and results in genomic instability. This conclusion is supported by previous observations that cell lines stably over-expressing APE1 show genomic instability (41). Ubr3-knockout mice were able to be generated depending on the genetic background, which results in early embryonic lethality or neonatal lethality caused by a number of pathologies, although the reason for this at that time remained unclear (28). Our current study may partially explain the observed phenotype of Ubr3-knockout mice and it is quite possible that the different abilities of the 1239vImJ and C57BL/6 mice, used to generate the Ubr3-knockout mice, to tolerate DNA double-strand breaks may be one of the reasons for the differential effects of the knockout.

In summary, we propose that newly synthesized cytoplasmic APE1 is directly transferred to the nucleus, where it is able to participate in DNA repair. However if the level of APE1 exceeds the amount required for DNA damage repair, then APE1 is ubiquitylated by UBR3 and becomes a target for proteasomal degradation. An important question that remains unanswered is how cells would know whether they need more or less APE1 and to make the decision whether or not to ubiquitylate APE1. In other words, how is the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of UBR3 on APE1 regulated? It is possible that other post-translational modifications of APE1, including recently reported phosphorylation (42) and acetylation (43), may modulate its stability, activity or subcellular localization in response to DNA damage by controlling UBR3 ubiquitylation and we are currently investigating this hypothesis.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Funding for open access charge: Medical Research Council and Cancer Research UK (to G.L.D.); National Institute of Health grant GM074000 and HL083365 (to Y.T.K.); World Class University and World Class Institute programs of the NRF and the MEST (grant number R31-2008-000-10103-0 to Y.T.K.); Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR) Oxford, UK (to B.M.K.).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Drs I. Hickson and Y. Nakabeppu for providing expression vectors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lindahl T, Nyberg B. Rate of depurination of native deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1972;11:3610–3618. doi: 10.1021/bi00769a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindahl T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature. 1993;362:709–715. doi: 10.1038/362709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robson CN, Hochhauser D, Craig R, Rack K, Buckle VJ, Hickson ID. Structure of the human DNA repair gene HAP1 and its localization to chromosome 14q 11.2-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4417–4421. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.17.4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demple B, Herman T, Chen DS. Cloning and expression of APE, the cDNA encoding the major human apurinic endonuclease: definition of a family of DNA repair enzymes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:11450–11454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dianov GL, Sleeth KM, Dianova II, Allinson SL. Repair of abasic sites in DNA. Mutat. Res. 2003;531:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson DM, Barsky D. The major human abasic endonuclease: formation, consequences and repair of abasic lesions in DNA. Mutat. Res. 2001;485:283–307. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(01)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winters TA, Henner WD, Russell PS, McCullough A, Jorgensen TJ. Removal of 3′-phosphoglycolate from DNA strand-break damage in an oligonucleotide substrate by recombinant human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1866–1873. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.10.1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Izumi T, Hazra TK, Boldogh I, Tomkinson AE, Park MS, Ikeda S, Mitra S. Requirement for human AP endonuclease 1 for repair of 3′- blocking damage at DNA single-strand breaks induced by reactive oxygen species. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1329–1334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suh D, Wilson DM, 3rd, Povirk LF. 3′-phosphodiesterase activity of human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease at DNA double-strand break ends. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2495–2500. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.12.2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parsons JL, Dianova II, Dianov GL. APE1 is the major 3′-phosphoglycolate activity in human cell extracts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:3531–3536. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tell G, Damante G, Caldwell D, Kelley MR. The intracellular localization of APE1/Ref-1: more than a passive phenomenon? Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2005;7:367–384. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meira LB, Devaraj S, Kisby GE, Burns DK, Daniel RL, Hammer RE, Grundy S, Jialal I, Friedberg EC. Heterozygosity for the mouse Apex gene results in phenotypes associated with oxidative stress. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5552–5557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludwig DL, MacInnes MA, Takiguchi Y, Purtymun PE, Henrie M, Flannery M, Meneses J, Pedersen RA, Chen DJ. A murine AP-endonuclease gene-targeted deficiency with post-implantation embryonic progression and ionizing radiation sensitivity. Mutat. Res. 1998;409:17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(98)00039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xanthoudakis S, Smeyne RJ, Wallace JD, Curran T. The redox/DNA repair protein, Ref-1, is essential for early embryonic development in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. USA. 1996;93:8919–8923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fung H, Demple B. A vital role for ape1/ref1 protein in repairing spontaneous DNA damage in human cells. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Izumi T, Brown DB, Naidu CV, Bhakat KK, Macinnes MA, Saito H, Chen DJ, Mitra S. Two essential but distinct functions of the mammalian abasic endonuclease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:5739–5743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500986102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sossou M, Flohr-Beckhaus C, Schulz I, Daboussi F, Epe B, Radicella JP. APE1 overexpression in XRCC1-deficient cells complements the defective repair of oxidative single strand breaks but increases genomic instability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:298–306. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unnikrishnan A, Raffoul JJ, Patel HV, Prychitko TM, Anyangwe N, Meira LB, Friedberg EC, Cabelof DC, Heydari AR. Oxidative stress alters base excision repair pathway and increases apoptotic response in apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1/redox factor-1 haploinsufficient mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;46:1488–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huamani J, McMahan CA, Herbert DC, Reddick R, McCarrey JR, MacInnes MI, Chen DJ, Walter CA. Spontaneous mutagenesis is enhanced in Apex heterozygous mice. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:8145–8153. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8145-8153.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freitas S, Moore DH, Michael H, Kelley MR. Studies of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease/ref-1 expression in epithelial ovarian cancer: correlations with tumor progression and platinum resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:4689–4694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore DH, Michael H, Tritt R, Parsons SH, Kelley MR. Alterations in the expression of the DNA repair/redox enzyme APE/ref-1 in epithelial ovarian cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:602–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu Y, Moore DH, Broshears J, Liu L, Wilson TM, Kelley MR. The apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease (APE/ref-1) DNA repair enzyme is elevated in premalignant and malignant cervical cancer. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:3713–3719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sak SC, Harnden P, Johnston CF, Paul AB, Kiltie AE. APE1 and XRCC1 protein expression levels predict cancer-specific survival following radical radiotherapy in bladder cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:6205–6211. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcon G, Tell G, Perrone L, Garbelli R, Quadrifoglio F, Tagliavini F, Giaccone G. APE1/Ref-1 in Alzheimer's disease: an immunohistochemical study. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;466:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parsons JL, Tait PS, Finch D, Dianova II, Allinson SL, Dianov GL. CHIP-mediated degradation and DNA damage-dependent stabilization regulate base excision repair proteins. Mol. Cell. 2008;29:477–487. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsons JL, Tait PS, Finch D, Dianova II, Edelmann MJ, Khoronenkova SV, Kessler BM, Sharma RA, McKenna WG, Dianov GL. Ubiquitin ligase ARF-BP1/Mule modulates base excision repair. EMBO J. 2009;28:3207–3215. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dianova II, Bohr VA, Dianov GL. Interaction of human AP endonuclease 1 with flap endonuclease 1 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen involved in long-patch base excision repair. Biochemistry. 2001;40:12639–12644. doi: 10.1021/bi011117i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tasaki T, Sohr R, Xia Z, Hellweg R, Hortnagl H, Varshavsky A, Kwon YT. Biochemical and genetic studies of UBR3, a ubiquitin ligase with a function in olfactory and other sensory systems. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:18510–18520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701894200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tasaki T, Mulder LC, Iwamatsu A, Lee MJ, Davydov IV, Varshavsky A, Muesing M, Kwon YT. A family of mammalian E3 ubiquitin ligases that contain the UBR box motif and recognize N-degrons. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:7120–7136. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.7120-7136.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka M, Lai JS, Herr W. Promoter-selective activation domains in Oct-1 and Oct-2 direct differential activation of an Snrna and messenger-Rna promoter. Cell. 1992;68:755–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woodhouse BC, Dianova II, Parsons JL, Dianov GL. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 modulates DNA repair capacity and prevents formation of DNA double strand breaks. DNA Repair. 2008;7:932–940. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Busso CS, Iwakuma T, Izumi T. Ubiquitination of mammalian AP endonuclease (APE1) regulated by the p53-MDM2 signaling pathway. Oncogene. 2009;28:1616–1625. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gisselsson D, Bjork J, Hoglund M, Mertens F, Dal Cin P, Akerman M, Mandahl N. Abnormal nuclear shape in solid tumors reflects mitotic instability. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;158:199–206. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63958-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans AR, Limp-Foster M, Kelley MR. Going APE over ref-1. Mutat. Res. 2000;461:83–108. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(00)00046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhakat KK, Mantha AK, Mitra S. Transcriptional regulatory functions of mammalian AP-endonuclease (APE1/Ref-1), an essential multifunctional protein. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11:621–638. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaky A, Busso C, Izumi T, Chattopadhyay R, Bassiouny A, Mitra S, Bhakat KK. Regulation of the human AP-endonuclease (APE1/Ref-1) expression by the tumor suppressor p53 in response to DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:1555–1566. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tasaki T, Kwon YT. The mammalian N-end rule pathway: new insights into its components and physiological roles. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007;32:520–528. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tasaki T, Zakrzewska A, Dudgeon DD, Jiang Y, Lazo JS, Kwon YT. The substrate recognition domains of the N-end rule pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:1884–1895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803641200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frosina G. Overexpression of enzymes that repair endogenous damage to DNA. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:2135–2149. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Foster ER, Downs JA. Histone H2A phosphorylation in DNA double-strand break repair. FEBS J. 2005;272:3231–3240. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hofseth LJ, Khan MA, Ambrose M, Nikolayeva O, Xu-Welliver M, Kartalou M, Hussain SP, Roth RB, Zhou X, Mechanic LE, et al. The adaptive imbalance in base excision-repair enzymes generates microsatellite instability in chronic inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:1887–1894. doi: 10.1172/JCI19757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang E, Qu D, Zhang Y, Venderova K, Haque ME, Rousseaux MW, Slack RS, Woulfe JM, Park DS. The role of Cdk5-mediated apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 phosphorylation in neuronal death. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:563–571. doi: 10.1038/ncb2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamamori T, DeRicco J, Naqvi A, Hoffman TA, Mattagajasingh I, Kasuno K, Jung SB, Kim CS, Irani K. SIRT1 deacetylates APE1 and regulates cellular base excision repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:832–845. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.