Abstract

Access to regulatory elements of the genome can be inhibited by nucleosome core particles arranged along the DNA strand. Hence, sites that are accessible by transcription factors may be located by using nuclease digestion to identify the relative nucleosome occupancy of a genomic region. In order to define novel cis regulatory elements in the ∼2.7-kb promoter region of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene, we define its nucleosome occupancy. This profile reveals the precise positions of nucleosome-free regions (NFRs), both cell-type specific and others apparently unrelated to CFTR-expression level and offer the first high-resolution map of the chromatin structure of the entire CFTR promoter in relevant cell types. Several of these NFRs are strongly bound by nuclear factors in a sequence-specific manner, and directly influence CFTR promoter activity. Sequences within the NFR1 and NFR4 elements are highly conserved in many human gene promoters. Moreover, NFR1 contributes to promoter activity of another gene, angiopoietin-like 3 (ANGPTL3), while NFR4 is constitutively nucleosome-free in promoters genome wide. Conserved motifs within NFRs of the CFTR promoter also show a high level of protection from DNase I digestion genome-wide, and likely have important roles in the positioning of nucleosome core particles more generally.

INTRODUCTION

Transcriptional regulation of genes depends in part on interactions between DNA-binding transcription factors and their cognate genomic regulatory elements. These interactions are profoundly influenced by the chromatin structure associated with a given regulatory element: transcription factors are less likely to bind to sequences found in condensed heterochromatic regions than those in more 'open' euchromatic genomic regions. The fundamental unit of chromatin structure, the nucleosome, is a primary barrier for transcription factor binding. Thus, heterochromatin is characterized by densely packed nucleosomes that can adopt higher-order fiber structures, while euchromatic nucleosomes are less compacted and hence less of the double-stranded genomic DNA is nucleosome-bound. Within euchromatic regions of the genome, the positioning of nucleosomes relative to the DNA strand is determined in an active manner by chromatin remodeling enzymes (1), and in a passive manner by the DNA sequence itself and binding competition with transcription factors (2). The relative contribution of these influences is a matter of some debate, yet it remains clear that within the important regulatory regions of any gene, such as the promoter and its enhancers, the elements required for transcriptional control are more likely to be free from the nucleosome core particle.

Here, we describe the use of measurements of nucleosome occupancy within the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene promoter to predict the locations of novel regulatory elements. The promoter of CFTR, the causal gene for cystic fibrosis, has similarities to housekeeping gene promoters in that it lacks a TATA-box, is GC-rich and contains several putative binding sites for the Sp1 GC box-binding transcription factor (3–5). However, CFTR expression is restricted to specific cell types, which include specialized epithelial cells in the airway, pancreas, small intestine and male genital ducts (6–10), among others (11–13). Several important regulatory elements that help determine this tissue-specific expression pattern were identified outside the CFTR promoter and some were shown to directly interact with it (14–23). Thus, while the promoter alone does not coordinate the cell-type specific transcriptional regulation of the CFTR gene, it is an important conduit for enhancer-mediated regulatory cues, which are likely interpreted and relayed to the general promoter-associated RNA polymerase II machinery by multiple bound transcription factors. Indeed, regulatory regions were characterized that include a cyclic AMP response element (CRE) (24,25), an inverted Y-box (26,27), an NF-κB binding site (28) and a CArG-like motif (29). These elements contribute to transcriptional initiation from several transcriptional start sites mapped in different CFTR-expressing cell types (3–5,30). Furthermore, a number of genetic alterations were detected in the promoter region of cystic fibrosis patients including single-nucleotide changes and deletions. These may cause disease or influence the disease phenotype either positively (31) or negatively (32) (see the Cystic Fibrosis Mutation Database at www.genet.sickkids.on.ca). We found that in addition to these characterized features of the CFTR promoter, specific nucleosome-depleted regions bind nuclear factors and contribute to promoter activity. Several motifs in these nucleosome-depleted regions are highly conserved and found in many promoters throughout the genome. These studies enable a more intricate understanding of the regulatory mechanisms at work in the complex CFTR promoter region. Moreover, they provide a detailed description of the chromatin architecture that contributes to the inactive and active state of the gene, and demonstrate a robust experimental approach for regulatory element discovery at specific genomic regions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Micrococcal nuclease assays

Micrococcal nuclease (MNase) was used to generate mononucleosomal DNA fragments for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)-based nucleosome occupancy analysis. 1 × 107 cells were resuspended in 10 ml media [Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium with 10% serum] and crosslinked with 0.37% formaldehyde for 10 min on a rocker, and quenched with the addition of 1.5 ml 1M glycine. The cells were then pelleted and washed 2X with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in 500 µl Resuspension buffer (RSB) (10 mM Tris–Cl pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2), and lysed with 0.1% NP-40 (dissolved in 14 ml RSB). The cells were inverted 10X in the NP-40/RSB, to aid lysis; the tube was then spun to pellet nuclei. Nuclei were resuspended in 1 ml RSB and 1500 U MNase (Fermentas) was added. The sample was digested O/N at 37°C with gentle shaking. Following digestion, 10 µl RNase was added and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Then, 10 µl proteinase K was added and incubated at 45°C for 1 h. The sample was then extracted with phenol:chloroform: isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1 v/v) and ethanol precipitated. The DNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and resuspended in 50 µl H2O. A small sample was then run on a 2% agarose gel to check for adequate digestion (a predominant ∼150-bp band). As a control, undigested genomic DNA was prepared as above with no MNase added. The samples were diluted to a concentration of 5 ng/µl using the Quant-iT™ PicoGreen® ds-DNA kit (Invitrogen) and a Turner Biosystems fluorimeter.

Primer sets for qPCR analysis of mononucleosomal DNA were designed to amplify ∼60–80-bp regions of the promoter region with ∼20-bp overlaps. A standard curve for each primer set was generated using a serial dilution of genomic DNA, and the respective amplification efficiency for each primer set was determined. Primers used in these assays are listed in Supplementary Table S1. All PCR products were run on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and stained with ethidium bromide to confirm a single major amplification product. To determine the relative nucleosome occupancy associated with each primer set, the following equation was used:

where m is the slope taken from the standard curve generated for each primer set. Nucleosome occupancy maps were generated by plotting the midpoints of each amplicon relative to the CFTR translational start site versus the MNase/No MNase nucleosome occupancy ratio calculated as above. A best-fit cubic spline curve was then fitted to the data points using the Prism® statistical program (GraphPad Software).

qRT-PCR

CFTR expression was assayed as described previously using a Taqman primer/probe set spanning CFTR exons 5 and 6 (TAQEX5/6) (33).

Electromobility shift assays

Complementary single-stranded oligonucleotides (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S1 for sequences) were annealed and labeled with [α-32P]-dCTP by fill-in reactions with Klenow DNA polymerase, prior to purification with microspin G-25 columns (Amersham Biosciences). Labeled DNA probes were incubated for 15 min with 5 µg nuclear extract in a final reaction volume of 20 µl containing 20% (v/v) glycerol, 20 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 4 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 32 mM NaCl, 0.4 µg/µl bovine serum albumin (BSA), 20 mM DTT and 0.05 µg/µl poly(dI–dC). For competition electromobility shift assay (EMSA), the nuclear extract was preincubated with unlabeled oligonucleotide duplexes at 10-, 50- and 100-fold excess molar concentrations for 20 min at room temperature before addition of labeled DNA. The samples were resolved on a 4% polyacrylamide gel at 4°C for 1.5 h at 300 V. Following electrophoresis, gels were dried and exposed to a phosphorimager screen.

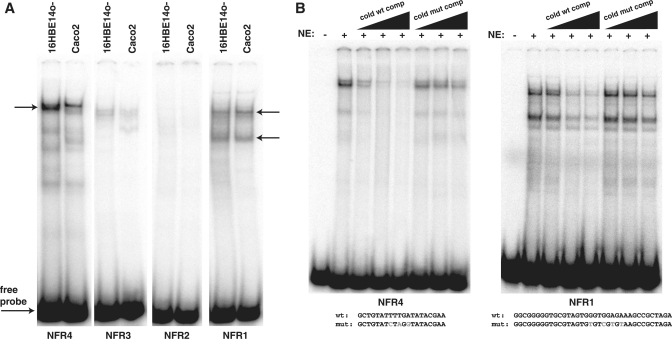

Figure 4.

In vitro binding of protein complexes to CFTR promoter NFRs. (A) EMSA with probes spanning regions of NFRs 1–4 using nuclear extract from the CFTR-expressing cell types Caco2 and 16HBE14o-. Major complexes are observed with probes for NFR4 (single arrow) and NFR1 (two arrows), while NFRs 2 and 3 show very slight protein complex formation. (B) Specificity of complex formation with 16HBE14o- nuclear extracts shown by EMSAs with unlabeled NFR4 and NFR1 oligonucleotides. These efficiently compete complex formation at 10-, 50- and 100-fold molar excess, while mutant oligos (mutated bases shown in gray) are inefficient competitors up to 100-fold molar excess.

Cell culture

The human colon carcinoma cell lines Caco2 (34), SV40 immmortalized 16HBE14o- bronchial epithelial cells (35), Beas-2B cells (36) and MCF7 cells (37) were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Primary skin fibroblasts (GM08333) (38) were grown in MEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 15% FBS. Primary tracheal epithelial cells were extracted from post-mortem human adult trachea as previously described with minor modifications (39). Normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells, a mixture of primary human bronchial and tracheal epithelial cells (Lonza, CC-2541) were cultured in BEGM (Lonza) per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Promoter:reporter transient transfection assays

Construction of the pGL3.2 kb CFTR promoter-Luciferase reporter plasmid has been described previously (40). The ANGPTL3 promoter (chr1:63,062,266-63,063,303; hg19) was amplified by PCR from human genomic DNA and cloned into the pGL3-Basic vector (Promega) to create pGL3B-ANGPTL3. Point mutations in the pGL3.2 kb CFTR plasmid and pGL3B-ANGPTL3mutNFR1 were generated using the QuikChange Mutagenesis kit or the Lightning Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene/Agilent) per the manufacturer's instructions using primers listed in Supplementary Table S1. For pGL3.2 kb CFTR transient transfection assays, 16HBE14o- cells were seeded onto 24-well plates and transfected with Lipofectin (Invitrogen) 24 h post-seeding. A pCMV-β-galactosidase plasmid was co-transfected to control for transfection efficiency. Cells were lysed 36 h post-transfection and assayed for Luciferase and β-galactosidase activity with appropriate substrate reagents (Promega). For pGL3B-ANGPTL3/pGL3B-ANGPTL3mutNFR1 constructs, Caco-2 cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) 48 h after plating. Luciferase and β-galactosidase assays were performed 48 h post-transfection. Data were analyzed for statistical significance using an unpaired t-test with Welch's correction.

Genomic motif analysis

To examine the predicted nucleosome occupancy and DNase hypersensitivity of genomic motifs in promoter regions, the refFlat.txt file, which denotes the genomic indices of all human RefSeq genes, was downloaded from the UCSC genome browser (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg18/database/). A program was written to read this file and generate a list of indices of the 2-kb upstream region of all protein-coding genes. Next, a FASTA file of the genomic DNA corresponding to these promoter indices was generated and the genomic motifs of interest were identified among these sequences. Each occurrence was recorded along with its genomic position. These genomic sequences and flanking genomic regions were then analyzed with NuPoP (http://nucleosome.stats.northwestern.edu), a software tool for nucleosome position prediction (41). The NuPoP score at each nucleotide position was then averaged over all sequences. These genomic indices were also used to extract the DNase hypersensitivity values (specifically the DNase-Seq Base Overlap Signal) of the genomic DNA within and surrounding each motif, from the ENCODE Open Chromatin Map generated by Dr G Crawford, Duke University (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg18/encodeDCC/wgEncodeChromatinMap/). These values were then averaged and plotted to generate a graph of the average DNase-Seq Base Overlap Signal surrounding the motifs. The same analysis was performed with conservation data to illustrate the average DNA conservation surrounding the motifs. The conservation values generated by PhastCons were downloaded from the UCSC genome browser (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg18/phastCons28way/vertebrate/).

RESULTS

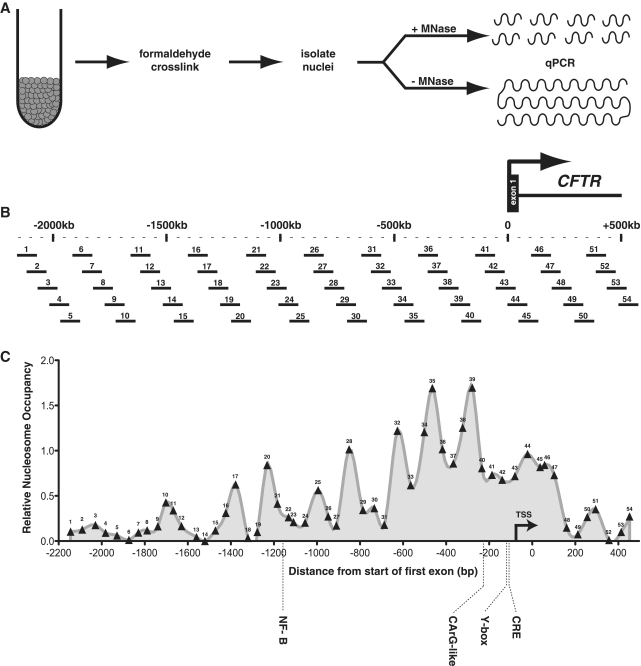

Nucleosome occupancy of the human CFTR promoter region

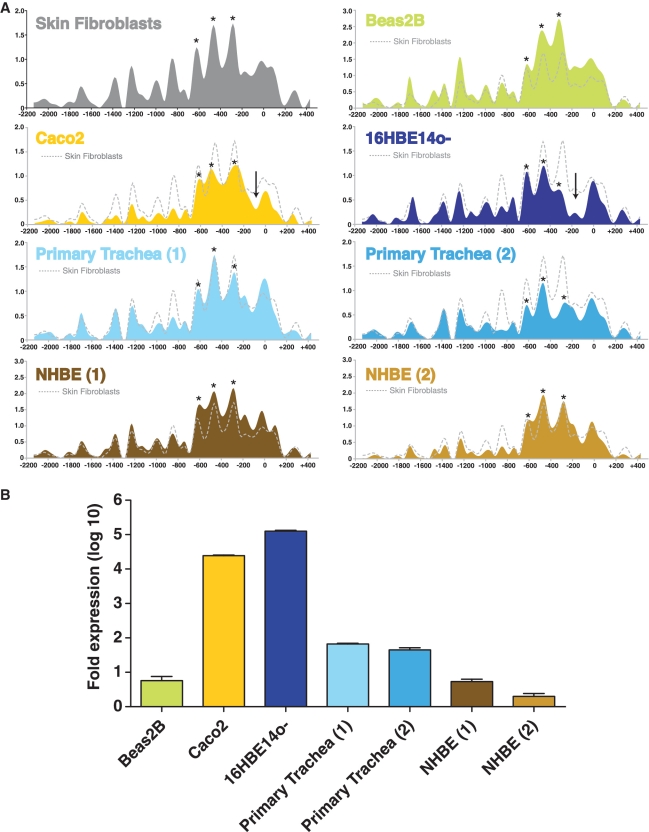

An MNase assay was used to determine the positioning and relative occupancy by nucleosomes in a region including ∼2200 bp upstream of the start of the CFTR translational start site to 500 bp into the first intron. A schematic of the assay design is shown in Figure 1A. MNase preferentially cleaves non-nucleosomal linker DNA, and was used to generate mononucleosomal DNA fragments (∼150 bp), which were then used as a template for qPCR with 54 overlapping PCR primer sets that were designed across the region. Each primer set amplified a ∼60–80 bp product with an average of ∼20 bp overlaps to achieve mononucleosome resolution (Figure 1B). Crosslinked chromatin from six different cell types was digested with MNase: primary human tracheal epithelial (HTE) cells and primary human bronchial epithelial and tracheal cells (NHBE) both of which express very low levels of CFTR, the CFTR-expressing human cell lines Caco2 (colon carcinoma) and 16HBE14o- (immortalized bronchial epithelial), and the CFTR low-expressing bronchial epithelial cell line Beas2B. Also assayed were human skin fibroblast cells, which do not express CFTR (21). As a normalizing control, equal amounts of undigested genomic DNA were also assayed in the qPCR reactions. The relative nucleosome occupancy across the region in skin fibroblasts, expressed as the ratio of MNase-digested to undigested controls, is shown as an example in Figure 1C and for each cell type in Figure 2A. Biological replicates for the primary airway samples are also shown in Figure 2A, and for each other cell type along with data for the breast adenocarcinoma cell line MCF7, another known CFTR-negative cell type, in Supplementary Figure S1. Active promoters generally possess well-positioned nucleosomes at either side of the core promoter region, defined as the region containing the transcriptional start site(s) of the gene and consensus general transcription factor binding elements such as the TATA-box, initiator (Inr), and others (42). The MNase assay detected positioned (or phased) nucleosomes throughout the interrogated region, with the most well-positioned nucleosomes flanking the region containing the transcriptional start sites and most well-characterized trans-factor binding sites in each cell type, regardless of expression level (Figures 1C and 2A), (quantitated expression levels for each cell type shown in Figure 2B). A nucleosome-depleted region that identifies the core promoter lies ∼100–220 bp upstream of the translational start site in 16HBE14o- cells, yet appears to be narrower in Caco2 cells (Figure 2A, vertical arrows), perhaps a cause or consequence of cell-type specific differences in the use of core promoter elements between these cells. In both cell types that do not express significant levels of CFTR transcript (skin fibroblasts and Beas2B cells), this core promoter region has higher relative nucleosome occupancy. Moreover, in the primary tracheal (HTE) and bronchial (NHBE) cells, which show levels of CFTR expression that fluctuate in culture but are low in comparison to 16HBE14o- and Caco2 cells, there is some variability in the nucleosome within the core promoter. Nucleosomes are clearly depleted over the core promoter in the high expressing cells, most notably 16HBE14o- but also Caco2 cells, relative to the CFTR-negative cell types. However, there is comparatively little difference between the core promoter nucleosome occupancy of the CFTR-negative skin fibroblasts, the low expressing Beas2B and primary airway cells, despite a ∼10–100-fold difference in transcript levels. This could mean that either little or no nucleosome displacement over the core promoter is required for low levels of transcription, or the nuclease assay is not sensitive enough to detect small changes in nucleosome occupancy that correlate with minor alterations in transcriptional activity in these particular cell types. Interestingly, in all cell types three well-positioned nucleosomes are seen between ∼ 220 and 700 bp upstream of the translational start site (Figure 2A, stars). Nucleosomes also occupy consistent positions further upstream, including two nucleosomes that flank a poly A:T tract, a sequence known to displace nucleosomes (43) at ∼−1300 bp.

Figure 1.

A high-resolution nucleosome occupancy assay of the human CFTR promoter region. (A) A schematic of the MNase assay procedure: harvested cells are crosslinked with formaldehyde, lysed for isolation of nuclei, and digested with MNase. An undigested genomic DNA sample is also prepared as a reference control. Both the digested and undigested samples are used as templates in qPCR reactions with overlapping primer sets tiled across the greater promoter region (B). The scale shown is relative to the first base of the first coding CFTR exon. The assayed region includes ∼2.2 kb 5′ and 500 bp 3′ of the translation start site. The 54 primer sets used in the assays are numbered 5′–3′. (C) The nucleosome occupancy profile for skin fibroblast cells; numbers along the profile indicate the midpoint of each assayed amplicon. Locations of known promoter regulatory elements and their cognate trans factors are shown.

Figure 2.

Nucleosome occupancy profiles. (A) Data collected from six cell types: high-expressing Caco2 and 16HBE14o- cells, low-expressing Beas2B and primary airway epithelial cells [primary tracheal (HTE) epithelial and normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE)], and CFTR-negative skin fibroblasts. The y-axis represents the ratio of MNase-digested amplified product to undigested product, while the x-axis represents the coordinates of the qPCR amplicons. Each experimental value is plotted at the midpoint of the amplicon, and lines are generated using a best-fit cubic spline curve. The skin fibroblast trace (gray dotted line) is reproduced on each graph for comparison to a CFTR-negative cell type. Each qPCR reaction was performed in duplicate; error bars are omitted for clarity, and data for a second biological replicate for 16HBE14o-, Caco2, Beas2B and skin fibroblast cells is included in Supplementary Figure S1. Arrows on Caco2 and 16HBE14o- tracks signify the estimated core promoter region. Asterisks on each track show positions of 3 positioned nucleosomes 5′ to the core promoter region. (B) CFTR mRNA levels for each cell type measured by qRT–PCR. Each value is shown as fold difference from skin fibroblast RNA; error bars represent SEM, n = 3.

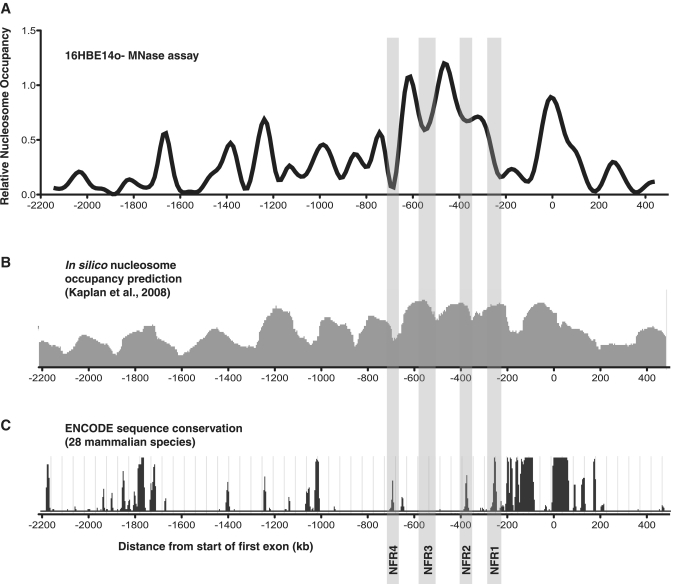

Nucleosome-free regions of the CFTR promoter contain highly conserved elements

Because the DNA wrapped around the nucleosome core particle can often occlude regulatory motifs from their cognate binding partners, we reasoned that nucleosome-free regions (NFRs) of the CFTR promoter would contain potential cis regulatory elements. Moreover, we sought any sites that might be devoid of nucleosomes in a cell-type-specific manner. Observing the nucleosome occupancy profile of CFTR-expressing bronchial epithelial 16HBE14o- cells revealed the region from ∼200 to 250 bp upstream of the first exon that is specifically nucleosome-depleted when compared to the other cell types, including the CFTR-expressing Caco2 cells (Figures 2A and 3A). This region is predicted to be concealed by a well-positioned nucleosome based on its sequence characteristics as determined by the nucleosome occupancy model developed by Kaplan et al. (44) (Figure 3B). The other NFRs that flank or lie between the three well-phased nucleosomes that lie immediately 5′ of the core promoter [and that are relatively consistently positioned between all the cell types assayed (Figure 2, stars)] align very closely with the sequence-based prediction algorithm.

Figure 3.

Nucleosome free (or depleted) regions of the CFTR promoter contain potential regulatory elements. (A) The nucleosome occupancy profile of the CFTR-expressing bronchial epithelial cell line 16HBE14o-. Highlighted are the nucleosome-free regions (NFRs 1–4) that fall between or flank the ∼3 relatively well-positioned nucleosomes that lie immediately 5′ of the 'core' CFTR promoter that contains the major transcriptional start sites. The x-axis is numbered as in Figure 1. (B) The predicted nucleosome occupancy (based solely on DNA sequence) of the CFTR promoter region derived by using the in silico model proposed in ref. 44 (C) The assayed region of the CFTR promoter aligned with the PhastCons mammalian species conservation track from the ENCODE Consortium (http://genome.ucsc.edu/ENCODE). Higher peaks represent increased sequence conservation among 28 mammalian genome alignments.

When the nucleosome occupancy data are aligned with a sequence conservation track (PhastCons) of 28 mammalian species developed for the ENCODE Consortium (45), strikingly many of the most conserved regions fall within NFRs (Figure 3C). Of the four NFRs that flank or lie between the three phased nucleosomes from −220 to −700 bp (referred to as NFR1-4, highlighted in Figure 3C), three (NFR1, NFR2 and NFR4) contain elements that correspond to high sequence conservation. We define NFR1 as the most 5′ region of the large nucleosome-depleted transcriptional start region observed in 16HBE14o- cells. It is interesting that this region is nucleosome-protected in the other cell types, yet contains a specific region of high conservation, which may suggest the presence of a unique regulatory element uniquely accessible in the 16HBE14o- cell type. As these NFRs flank some of the most well-phased nucleosomes of the CFTR promoter region, and lie relatively close to the promoter core, we focused on these regions, especially the conserved elements within them, to determine if they may contribute to CFTR transcriptional regulation.

NFR1 and NFR4 bind protein complexes in vitro

To determine the protein-binding capability of NFRs 1–4, we designed double-stranded oligonucleotides that spanned the highly conserved regions of each (no highly conserved element exists within NFR3, so a probe was designed to span the estimated center of the NFR). These probes were used in EMSAs together with nuclear extracts from CFTR-expressing 16HBE14o- and Caco2 cells (Figure 4A). With both nuclear extracts, the conserved regions of NFR1 and NFR4 strongly bound protein complexes, while NFR2 and NFR3 showed faint shifts. The NFR4 probe generated a single major complex (Figure 4A, left arrow) which was more abundant with the 16HBE14o- nuclear extract, while additional minor complexes were also present. The NFR1 probe generated two distinct and abundant complexes (Figure 4A, right arrows) with both nuclear extracts, with additional minor complexes. These protein complexes however are not unique to cells expressing high levels of CFTR, as nuclear extract purified from Beas2B cells formed the same complexes (Supplementary Figure S2). To establish that these protein complexes were generated by sequence-specific binding to the probes, EMSAs were performed with both the NFR1 and NFR4 probes using 16HBE14o- nuclear extract and competition with increasing amounts of unlabelled probe (10-, 50- and 100-fold molar excess) (Figure 4B). Complex formation with both NFR1 and NFR4 labeled probes was efficiently disrupted by excess cold probe but not by mutant probes in which either three (NFR4) or four (NFR1) bases within the highly conserved element were mutated.

In an effort to determine the identity of the factors that bind to these elements, the critical core sequences were analyzed by the MatInspector transcription factor binding prediction program (Genomatix, www.genomatix.de), which did not predict binding by any known factors. Although NFR4 contains a GATA base sequence, this is not in the (A/T)GATA(A/G) context of the consensus for GATA transcription factor binding. However, some GATA factors are known to bind alternative consensus sites (46) and thus NFR4 may represent a constitutively accessible site for some GATA factors.

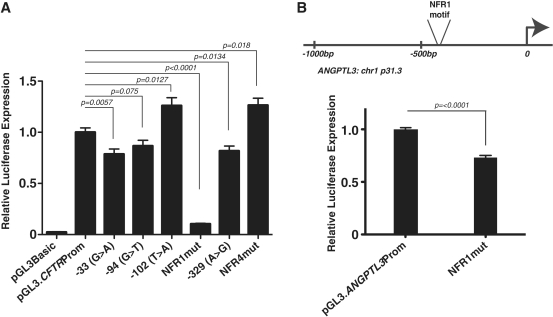

The NFR1 and NFR4 conserved elements contribute to CFTR transcriptional regulation

To determine if these motifs and the factors they recruit in vitro have any direct influence on CFTR promoter activity, we performed transient transfections in 16HBE14o- cells using reporter vectors with ∼2 kb of the wild-type CFTR promoter cloned 5′ of the luciferase gene. We previously showed that this 2 kb sequence, which encompasses the minimal 'core' promoter region and other known regulatory elements upstream, maximally activates gene expression in these assays in 16HBE14o- cells (40). The same base pairs were mutated in both NFR1 and NFR4 as in the EMSA competition experiments (Figure 4). Mutating 4 bp in NFR1 resulted in a significant decrease (90%, P < 0.0001) in promoter activity relative to the wild-type sequence, which suggests that the factor that binds to this motif is an activating transcription factor. Conversely, a 3 bp change in the NFR4 motif marginally increased promoter activity (26%, P = 0.018), suggesting that the factor that binds to this site plays a different role at the CFTR promoter.

Several mutations in the CFTR promoter, which occur at trans factor binding sites of regulatory elements, were previously identified in CF patients (6,32). Hence, the impact of mutations in the NFRs compared to known regulatory element mutations was of interest. To evaluate these relative effects of NFR1/NFR4 mutations on CFTR promoter activity we generated reporter vectors that contained promoter mutations/polymorphisms that were identified in CF patients. Three of these variants were previously tested in a much smaller basal CFTR promoter fragment (362 bp, compared to 2 kb used in the current studies) driving luciferase expression in reporter vectors. The −33G>A mutation alters a predicted FoxI1 site and reduced CFTR promoter activity by about 50% in immortalized male genital duct epithelial cells (6,47). The −94G>T mutation disrupts Sp1/USF binding and decreased CFTR promoter activity by about 30% in a cell-type-specific manner (32). The −102T>A polymorphism, which correlates with milder forms of disease (31,48), introduces a binding site for the transcription factor YY1, increasing CFTR promoter activity by about 45–66% depending on the cell type used for transient transfections. The −329C>T mutation/ polymorphism (CF Mutation database, unpublished, submitted by Wallace and Tassabehji, St. Mary's Hospital, Manchester, England), which has not been evaluated previously, was also introduced into the 2 kb CFTR promoter fragment driving luciferase expression. All constructs were transfected into 16HBE14o- cells (Figure 5A) and demonstrate that though the effects of each mutation was smaller than reported in the 362-bp basal promoter in different cell types, the trends were similar. Specifically, −33G>A and −94C>T reduced promoter activity (21%, P = 0.0057 and 13%, respectively, P = 0.075 ns) as did −329C>T (18%, P = 0.0134). The −102A>T change augmented promoter strength (26%, P = 0.0127) similarly to the mutation of NFR4 (26%, P = 0.018). Of note, the −94C>T and −102T>A changes are located just 3′ of the NFR1 site within the CFTR core promoter region that is depleted of nucleosomes in 16HBE14o- cells. Most importantly the effect on promoter activity of mutating NFR1 is significantly greater (90%, P < 0.0001) than that seen in any of the disease-associated mutations, supporting its critical role in CFTR expression.

Figure 5.

(A) Mutation of NFR1 inhibits CFTR promoter activity more profoundly than several CF disease-associated mutations. 16HBE14o- cells were transfected with pGL3B luciferase reporter constructs containing the 2-kb CFTR greater promoter region (pGL3:2kbProm) and a β-galactosidase transfection control plasmid. Promoter mutants: 33G>A, −94G>T, −102T>A, NFR1mut, −329C>T and NFR4mut are shown relative to the CFTR basal promoter-alone vector. (B) Mutation of NFR1 in the ANGPTL3 promoter decreases promoter activity in Caco2 cells. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean [n = 6 or 9 (CFTR and ANGPTL3)]. P-values generated by comparison to the wild-type promoter-only vector by using unpaired t-tests with Welch's correction. Experiments were done a minimum of three times and with more than one plasmid preparation of each construct and results were consistent between them.

We next investigated whether the NFR1 motif has a similar role in transcriptional activation where it occurs in promoters at other locations in the genome (see below). We cloned the promoter of the angiopoietin-like 3 gene (ANGPTL3), which contains a single NFR1 motif (GTGGAGAAAG) 494 bp upstream of its first exon. Mutation of three bases in the NFR1 motif of the ANGPTL3 promoter resulted in a significant decrease in promoter activity (Figure 5B) (27%, P < 0.0001) when transiently transfected into Caco2 cells. Although the effect is slightly less than the CFTR NFR1 mutant in 16HBE14o- cells, these data demonstrate that this motif likely acts as a positive cis regulatory element at multiple promoter locations in the genome.

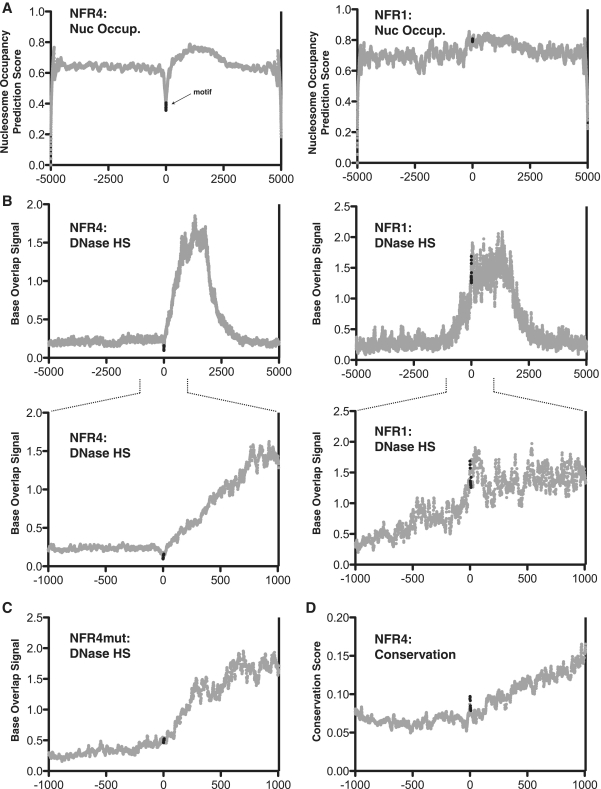

The NFR4 conserved motif is typically within nucleosome-depleted and DNase-protected regions of promoters

We then sought to determine whether these regulatory motifs of the CFTR promoter, which we first defined as a result of their chromatin-associated characteristics and conservation profile, may have the same characteristics genome wide. We searched every promoter in the genome (including up to 2 kb upstream of first exons) for both the NFR1 and NFR4 motifs (NFR1: GTGGAGAAAG; NFR4: TTTTGATA). The NFR1 motif occurs in 138 promoters while the shorter NFR4 motif occurs in 936 promoters. NFR1 is found twice in a single gene promoter (TSSC4), while NFR4 is found twice in 35 promoters and three times in two promoters (OR2G3 and SETDB2). To understand the chromatin-associated characteristics of all of these motifs, we used genome-wide nucleosome occupancy prediction analysis (NuPoP) (http://nucleosome.stats.northwestern.edu) (41) and DNase-hypersensitivity data available from the ENCODE Consortium (http://genome.ucsc.edu/ENCODE) (49). We compiled the surrounding sequences for each promoter motif (5 kb or 1 kb both 5′ and 3′ from the motif) and generated the average nucleosome occupancy prediction score, which is based solely on sequence characteristics of all promoter NFR1 and NFR4 sites across the genome. This analysis shows that the NFR4 motif is specifically disfavorable to nucleosome occupancy, while the NFR1 motif is neutral (Figure 6A). This corresponds to the nucleosome occupancy scores found for the CFTR promoter region itself (Figure 3B). Figure 6B shows genome-wide analysis of the same sequences and high-resolution DNase-hypersensitivity by overlapping 10 bp sequencing tags (5 bp on each end of a mapped DNase-digestion site). We generated the average base overlap values for each base surrounding the motif using datasets for HelaS3 (Figure 6B) and HepG2 (Supplementary Figure S3) cell lines. The average DNase-hypersensitivity profile of the NFR4 motif shows that throughout the promoter-associated genome, it occupies a specific localized region protected from DNase-cleavage, whereas the NFR1 motif is much less defined (Figure 6B). Interestingly, when the same analysis is performed on the 3-bp mutant version of the motif used in the reporter assays (427 occurrences in promoters) there is no longer a localized region of DNase protection (Figure 6C). This suggests that at promoters genome-wide, this motif is consistently bound by a trans factor that inhibits DNase digestion in a sequence-specific manner.

Figure 6.

Genome-wide promoter profile of NFR1 and NFR4. (A) The nucleosome occupancy prediction scores of all human promoters that contain either NFR1 or NFR4 motifs. Y-axis represents the NuPoP nucleosome occupancy score (see ‘Materials and Methods’ section for explanation). The x-axis represents the distance (in base pairs) from the start of the first base of the motif. The data points representing the motifs are shown in black, all other data points in gray. (B) The DNase I-hypersensitivity profiles of all human promoters that contain either NFR1 or NFR4 motifs. Y-axis represents the Base Overlap signal given by raw sequence data from DNase-seq experiments performed with HelaS3 cells. (C) The DNase I-hypersensitivity profile of all human promoters that contain the NFR4mut (mutant) motif. (D) The PhastCons score for the NFR4 motif across all human promoters.

Using the sequence conservation track generated by the ENCODE Consortium in which genome alignments from 28 mammalian species are compiled with the PhastCons algorithm peak tracks of sequence conservation, we generated the average conservation of promoter sequences flanking 2 kb 5′ and 3′ of the NFR4 motif genome wide. The NFR4 motif occupies a specific region of localized conservation, further signifying that this motif has important chromatin-associated regulatory properties in promoter regions (Figure 6D).

DISCUSSION

Understanding and deciphering the precise regulatory characteristics of the human genome is a significant challenge. Beyond the DNA sequence of genes, a significant amount of genomic regulatory capability is realized at the chromatin level, which can include both the post-translational modification of histones and positioning of nucleosomes. Thus, mapping precise nucleosome positions and their relative occupancy on the DNA strand can be a robust strategy for regulatory element discovery. While nuclease digestion of chromatin has long been used as a method for uncovering in vivo characteristics of genomic regions, the advent of precise quantitative PCR methods and more recently high-throughput sequencing of the whole genome have enabled increasingly precise analysis of genome structure. MNase was used to map nucleosome occupancy of the entire yeast (44), worm (50) and human genomes (51) with next-generation sequencing. However, the large size of the human genome currently prohibits sequence-based data generation at the high-resolution obtained here for the CFTR promoter using a qPCR method. Nevertheless, cumulatively these studies show that nucleosomes are often positioned away from specific sites for DNA-binding factors, and that nucleosomes have specific occupancy and positioning characteristics at promoter regions. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-sequencing has similarly been used to uncover nucleosome-depleted regions over human enhancers associated with histone H3 dimethylated lysine 4 marks (52), which also reveals specific depletion of nucleosomes over transcription factor binding sites.

Previous work uncovered a number of important transcriptional regulatory elements within the CFTR promoter (3–5,25,26,28,29) and enhancers elsewhere in the locus (23) some of which interact directly with the promoter region in vivo via a looping mechanism (21,22). The molecular machinery underlying these enhancer–promoter interactions must rely on the direct DNA-binding of specific trans factors to both cis-acting elements and the promoter. However, the identification of many of the trans-acting factors required for CFTR transcription has been challenging, particularly in airway epithelial cells. The cell types used in this study included epithelial cells of both airway and intestinal origin, to model tissue-specific expression of CFTR, and also skin fibroblasts, which lack CFTR. Several promoter NFRs were identified which were either constitutive or cell-type specific, yet despite a wide range of CFTR-expression levels, the nucleosome occupancy profile in each cell type was remarkably similar. This may signify that the CFTR promoter regulation is governed primarily by the relative presence of trans factors, or that the composition of histones at the promoter (i.e. modified histones and/or histone variants) plays a predominant role. While the MNase assay does not offer a direct quantitative correlation between core promoter nucleosome occupancy and mature transcript level, several qualitative characteristics can be discerned from the profiles. Some cell-type-specific NFRs do seem to signify elements of cell-type-specific promoter regulation. NFR1 is specifically nucleosome-depleted in 16HBE14o- cells when compared to the high-expressing intestinal Caco2 cell line and the other low-expressing primary cell types. As nuclear factors from both Caco2 and 16HBE14o- associate with this element in vitro, this may signify that an important aspect to CFTR transcription in 16HBE14o- cells could involve the activity of specific nucleosome remodelers that either evict or relocate a nucleosome away from this element to allow factor binding. Indeed, the NFR1 motif is not predicted to be nucleosome-depleted at either the CFTR promoter alone or throughout promoters of the genome, suggesting that trans factor access to this regulatory element requires the alteration of local chromatin structure. The larger nucleosome-depleted region of the core promoter in 16HBE14o- cells when compared to Caco2 cells, which express a similar level of CFTR transcript, may also indicate a tissue-specific characteristic that contributes to transcriptional regulation. NFR4, however, seems to represent a ‘barrier sequence' as has recently been described by others in yeast (53) and human primary cells (54), which is probably due to the TT dyads found in the motif. This motif is disfavorable to nucleosome occupancy, both at the CFTR promoter and in other promoters elsewhere in the genome, where it likely contributes to the positioning of nucleosomes that flank the motif. We provide evidence here that this `barrier' nucleosome-positioning sequence is bound by a sequence-specific trans factor, which may be responsible for its chromatin-organizing characteristics. In support of this, we show that this motif is specifically resistant to DNase I-cleavage genome wide, which indicates the presence of a unique bound factor at these sites. These localized DNase I-resistant sites have been reported with other motifs, although the identity of the trans factors responsible have not been identified (55). It seems probable that the nuclear proteins interacting with NFR1 and NFR4 may not be well-characterized transcription factors, since in silico transcription factor binding site prediction programs (Matinspector) failed to identify candidate interacting factors. Initial attempts to identify the nuclear factors that associate with NFR1 and NFR4 by DNA-affinity chromatography using biotinylated oligonucleotides did not isolate specific trans factors and will likely require significant advances in transcription factor isolation techniques for success. Alternatively, it may be possible to use indirect methods to capture the proteins interacting with the NFRs, by exploiting recent advances in understanding the three-dimensional structure of the active CFTR locus (21,22), The intronic enhancers that determine cell-type-specific expression of the gene are known to interact directly with the promoter via a looping mechanism. Moreover, some of the transcription factors that generate functional complexes at these enhancers are already known (20). Thus, a combination of ChIP-based techniques, among others, using these known factors as ‘bait’, may elucidate the trans-acting factors and co-factors that interact with the NFR elements at the promoter. These advances will provide further insights into general promoter architecture and how nucleosome positioning is maintained during transcriptional activation of CFTR. The fact that the NFR1 and NFR4 elements are found in multiple human gene promoters and that mutation of NFR1 in the ANGPTL3 promoter compromised its activity suggest these insights will be applicable to promoter function more generally.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

The National Institutes of Health (HL094585 to A.H.). Funding for open access charge: Institutional funds.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. C. Cotton (Case Western Reserve University) for human primary tracheal cell samples and Dr G. Crawford (Duke University) for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ho L, Crabtree GR. Chromatin remodelling during development. Nature. 2010;463:474–484. doi: 10.1038/nature08911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segal E, Widom J. From DNA sequence to transcriptional behaviour: a quantitative approach. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:443–456. doi: 10.1038/nrg2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou JL, Rozmahel R, Tsui LC. Characterization of the promoter region of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:24471–24476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koh J, Sferra TJ, Collins FS. Characterization of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator promoter region: chromatin context and tissue-specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:15912–15921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshimura K, Nakamura H, Trapnell BC, Dalemans W, Pavirani A, Lecocq JP, Crystal RG. The cystic fibrosis gene has a “housekeeping”-type promoter and is expressed at low levels in cells of epithelial origin. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:9140–9144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris A, Chalkley G, Goodman S, Coleman L. Expression of the cystic fibrosis gene in human development. Development. 1991;113:305–310. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crawford I, Maloney PC, Zeitlin PL, Guggino WB, Hyde SC, Turley H, Gatter KC, Harris A, Higgins CF. Immunocytochemical localization of the cystic fibrosis gene product CFTR. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:9262–9266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelhardt JF, Zepeda M, Cohn JA, Yankaskas JR, Wilson JM. Expression of the cystic fibrosis gene in adult human lung. J. Clin. Invest. 1994;93:737–749. doi: 10.1172/JCI117028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreda SM, Mall M, Mengos A, Rochelle L, Yankaskas J, Riordan JR, Boucher RC. Characterization of wild-type and deltaF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator in human respiratory epithelia. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:2154–2167. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strong T, Boehm K, Collins F. Localization of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator mRNA in the human gastrointestinal tract by in situ hybridization. J. Clin. Invest. 1994;93:347–354. doi: 10.1172/JCI116966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodges CA, Cotton CU, Palmert MR, Drumm ML. Generation of a conditional null allele for Cftr in mice. Genesis. 2008;46:546–552. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mueller C, Braag SA, Keeler A, Hodges C, Drumm M, Flotte TR. Lack of Cftr in CD3 + lymphocytes leads to aberrant cytokine secretion and hyper-inflammatory adaptive immune responses. Am. J. Resp. Cell Mol. Biol. 2011;44:922–929. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0224OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulberg AE, Weyler RT, Altschuler SM, Hyde TM. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator expression in human hypothalamus. Neuroreport. 1998;9:141–144. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199801050-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith AN, Wardle CJC, Harris A. Characterization of DNase I hypersensitive sites in the 120kB 5′ to the CFTR gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1995;211:274–281. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith AN, Barth ML, McDowell TL, Moulin DS, Nuthall HN, Hollingsworth MA, Harris A. A regulatory element in intron 1 of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:9947–9954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.9947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nuthall HN, Moulin DS, Huxley C, Harris A. Analysis of DNase-I-hypersensitive sites at the 3′ end of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene (CFTR) Biochem. J. 1999;341:601–611. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nuthall HN, Vassaux G, Huxley C, Harris A. Analysis of a DNase I hypersensitive site located −20.9 kb upstream of the CFTR gene. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;266:431–443. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith DJ, Nuthall HN, Majetti ME, Harris A. Multiple potential intragenic regulatory elements in the CFTR gene. Genomics. 2000;64:90–96. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.6086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phylactides M, Rowntree R, Nuthall H, Ussery D, Wheeler A, Harris A. Evaluation of potential regulatory elements identified as DNase I hypersensitive sites in the CFTR gene. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:553–559. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ott CJ, Suszko M, Blackledge NP, Wright JE, Crawford GE, Harris A. A complex enhancer regulates expression of the CFTR gene by direct interation with the promoter. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009;13:680–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ott CJ, Blackledge NP, Kerschner JL, Leir S-H, Crawford GE, Cotton CU, Harris A. Intronic enhancers coordinate epithelial-specific looping of the active CFTR locus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:19934–19939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900946106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gheldof N, Smith EM, Tabuchi TM, Koch CM, Dunham I, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Dekker J. Cell-type-specific long-range looping interactions identify distant regulatory elements of the CFTR gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4325–4336. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ott CJ, Harris A. Genomic approaches for the discovery of CFTR regulatory elements. Transcription. 2011;2:23–27. doi: 10.4161/trns.2.1.13693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonald RA, Matthews RP, Idzerda RL, McKnight GS. Basal expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene is dependent on protein kinase A activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:7560–7564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matthews RP, McKnight GS. Characterization of the cAMP response element of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:31869–31877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pittman N, Shue G, LeLeiko NS, Walsh MJ. Transcription of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator requires a CCAAT-like element for both basal and cAMP-mediated regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:28848–28857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li S, Moy L, Pittman N, Shue G, Aufiero B, Neufeld EJ, LeLeiko NS, Walsh MJ. Transcriptional repression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene, mediated by CCAAT displacement protein/cut homolog, is associated with histone deacetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:7803–7815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brouillard F, Bouthier M, Leclerc T, Clement A, Baudouin-Legros M, Edelman A. NF-κB mediates upregulation of CFTR gene expression in Calu-3 cells by interleukin-1β. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;276:9486–9491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006636200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.René C, Taulan M, Iral F, Doudement J, L'Honoré A, Gerbon C, Demaille J, Claustres M, Romey MC. Binding of serum response factor to cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator CArG-like elements, as a new potential CFTR transcriptional regulation pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5271–5290. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White NL, Higgins CF, Trezise AE. Tissue-specific in vivo transcription start sites of the human and murine cystic fibrosis genes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:363–369. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romey M-C, Pallares-Ruiz N, Mange A, Mettling C, Peytavi R, Demaille J, Claustres M. A naturally occurring sequence variation that creates a YY1 element in associated with increased cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:3561–3567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taulan M, Lopez E, Guittard C, René C, Baux D, Altieri JP, DesGeorges M, Claustres M, Romey MC. First functional polymorphism in CFTR promoter that results in decreased transcriptional activity and Sp1/USF binding. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;361:775–781. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mouchel M, Henstra SA, McCarthy VA, Williams SH, Phylactides M, Harris A. HNF1α is involved in tissue-specific regulation of CFTR gene expression. Biochem. J. 378:909–918. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fogh J, Wright WC, Loveless JD. Absence of HeLa cell contamination in 169 cell lines derived from human tumors. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 1977;58:209–214. doi: 10.1093/jnci/58.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cozens AL, Yezzi MJ, Kunzelmann K, Ohrui T, Chin L, Eng K, Finkbeiner WE, Widdicombe JH, Gruenert DC. CFTR expression and chloride secretion in polarized immortal human bronchial epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1994;10:38–47. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.1.7507342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reddel RR, De Silva R, Duncan EL, Rogan EM, Whitaker NJ, Zahra DG, Ke Y, McMenamin MG, Gerwin BI, Harris CC. SV40-induced immortalization and ras-transformation of human bronchial epithelial cells. Int. J. Cancer. 1995;61:199–205. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910610210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soule HD, Vazguez J, Long A, Albert S, Brennan M. A human cell line from a pleural effusion derived from breast carcinoma. J. Natl Canc. Inst. 1973;51:1409–1416. doi: 10.1093/jnci/51.5.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiss MF, Ray K, Fallon MD, Whyte MP, Fedde KN, Lafferty MA, Mulivor RA, Harris H. Analysis of liver/bone/kidney alkaline phosphatase mRNA, DNA, and enzymatic activity in cultured skin fibroblasts from 14 unrelated patients with severe hypophosphatasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1989;44:686–694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis PB, Silski CL, Kercsmar CM, Infeld M. Beta-adrenergic receptors on human tracheal epithelial cells in primary culture. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;258:71–76. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.1.C71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewandowska MA, Costa FF, Bischof JM, Williams SH, Soares MB, Harris A. Multiple mechanisms influence regulation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene promoter. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2010;43:334–341. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0149OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xi L, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Xia L, Flatow J, Widom J, Wang J-P. Predicting nucleosome positioning using a duration Hidden Markov Model. BMC Bioinformat. 2010;11:346. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang C, Pugh BF. Nucleosome positioning and gene regulation: advances through genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:161–172. doi: 10.1038/nrg2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Segal E, Widom J. Poly(dA:dT) tracts: major determinants of nucleosome organization. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2009;19:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaplan N, Moore IK, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Gossett AJ, Tillo D, Field Y, LeProust EM, Hughes TR, Lieb JD, Widom J, et al. The DNA-encoded nucleosome organization of a eukaryotic genome. Nature. 2009;458:362–366. doi: 10.1038/nature07667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siepel A, Bejerano G, Pedersen JS, Hinrichs AS, Hou M, Rosenbloom K, Clawson H, Spieth J, Hillier LW, Richards S, et al. Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes. Genome Res. 2005;15:1034–1050. doi: 10.1101/gr.3715005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ko LJ, Engel JD. DNA-binding specificities of the GATA transcription factor family. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993;13:4011–4022. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lopez E, Viart V, Guittard C, Templin C, René C, Méchin D, Georges MD, Claustres M, Romey-Chatelain MC, Taulan M. Variants in CFTR untranslated regions are associated with congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens. J. Med. Genet. 2011;48:152–159. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.081851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romey M-C, Guittard C, Chazalette J-P, Frossard P, Dawson KP, Patton MA, Casals T, Bazarbachi T, Girodon E, Rault G, et al. Complex allele [-102 T>A+S549R(T>G)] is associated with milder forms of cystic fibrosis than allele S549R(T>G) alone. Hum. Genet. 1999;105:145–150. doi: 10.1007/s004399900066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boyle AP, Davis S, Shulha HP, Meltzer P, Margulies EH, Weng Z, Furey TS, Crawford GE. High-resolution mapping and characterization of open chromatin across the genome. Cell. 2008;132:311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valouev A, Ichikawa J, Tonthat T, Stuart J, Ranade S, Peckham H, Zeng K, Malek JA, Costa G, McKernan K, et al. A high-resolution, nucleosome position map of C. elegans reveals a lack of universal sequence-dictated positioning. Genome Res. 2008;18:1051–1063. doi: 10.1101/gr.076463.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schones DE, Cui K, Cuddapah S, Roh TY, Barski A, Wang Z, Wei G, Zhao K. Dynamic regulation of nucleosome positioning in the human genome. Cell. 2008;132:887–898. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.He HH, Meyer CA, Shin H, Bailey ST, Wei G, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Xu K, Ni M, Lupien M, et al. Nucleosome dynamics define transcriptional enhancers. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:343–347. doi: 10.1038/ng.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mavrich TN, Ioshikhes IP, Venters BJ, Jiang C, Tomsho LP, Qi J, Schuster SC, Albert I, Pugh BF. A barrier nucleosome model for statistical positioning of nucleosomes throughout the yeast genome. Genome Res. 2008;18:1073–1083. doi: 10.1101/gr.078261.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Valouev A, Johnson SM, Boyd SD, Smith CL, Fire AZ, Sidow A. Determinants of nucleosome organization in primary human cells. Nature. 2011;474:516–520. doi: 10.1038/nature10002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mikula M, Gaj P, Dzwonek K, Rubel T, Karczmarski J, Paziewska A, Dzwonek A, Bragoszewski P, Dadlez M, Ostrowski J. Comprehensive analysis of the palindromic motif TCTCGCGAGA: a regulatory element of the HNRNPK promoter. DNA Res. 2010;17:245–260. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsq016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.