Abstract

Depression is a common, under-recognized, and under-treated problem that is independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality in CKD patients. However, only a minority of CKD patients with depression are treated with antidepressant medications or nonpharmacologic therapy. Reasons for low treatment rates include a lack of properly controlled trials that support or refute efficacy and safety of various treatment regimens in CKD patients. The aim of this manuscript is to provide a comprehensive review of studies exploring depression treatment options in CKD. Observational studies as well as small trials suggest that certain serotonin-selective reuptake inhibitors may be safe to use in patients with advanced CKD and ESRD. These studies were limited by small sample sizes, lack of placebo control, and lack of formal assessment for depression diagnosis. Nonpharmacologic treatments were explored in selected ESRD samples. The most promising data were reported for frequent hemodialysis and cognitive behavioral therapy. Alternative proposed therapies include exercise training regimens, treatment of anxiety, and music therapy. Given the association of depression with cardiovascular events and mortality, and the excessive rates of cardiovascular death in CKD, it becomes imperative to not only investigate whether treatment of depression is efficacious, but also whether it would result in a reduction in morbidity and mortality in this patient population.

Keywords: antidepressant, chronic kidney disease, depression, dialysis, treatment

Major depressive disorder, defined as a clinical syndrome lasting for 2 weeks during which time the patient experiences either depressed mood or anhedonia plus at least 5 of the 9 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM IV) criterion symptom domains,1,2 is very common among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and is associated with adverse outcomes.3–9 Whereas depression point prevalence is 2–10% in the general population,10 20% of CKD patients suffer from a major depressive episode,11,12 a prevalence even higher than reported for other chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and congestive heart failure.13,14 Depression results in substantial functional impairment and decreased quality of life in ESRD patients,15–17 and levels of depression and functional and occupational impairment do not remit spontaneously in untreated depressed patients.18 We showed that ESRD patients on chronic hemodialysis (HD) with depression are twice as likely to die or require hospitalization within a year as compared with those without depression,4 and are at risk for a 30% increase in both cumulative hospital days and number of hospitalizations.5 In a recent prospective observational cohort study of consecutively recruited stage 2–5 CKD predialysis patients, a diagnosis of current major depressive episode at baseline was associated with an increased risk of a composite of death, hospitalization, or progression to dialysis, independent of comorbidities and kidney disease severity (adjusted hazard ratio 1.86, 95% confidence interval 1.23, 2.84).9 Despite the high prevalence of depressive symptoms as well as depressive disorder among patients with CKD and ESRD and its association with poor outcomes, only a minority of chronic dialysis patients receive adequate diagnosis and treatment for depression.3,12,19 For example, in a retrospective analysis of the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension Cohort Study, Fischer et al.20 reported that only 20% of CKD participants with a Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score of >14 (above the threshold validated for depression) were prescribed antidepressant medications. Similarly, Watnick et al.12 reported that only 16% of ESRD patients initiating chronic HD with BDI scores of ≥15 were on antidepressants. In a prospective observational cohort of 98 prevalent HD patients, nephrologists were informed about a current diagnosis of depressive disorder based on DSM IV diagnostic criteria in 26% of cases.4 However, intervention was made in only 23% of these patients, defined as referral to mental health clinic, initiation of an antidepressant medication, or increasing the dose of previously prescribed antidepressant. Thus, a major challenge for clinicians is to develop strategies to better understand and manage depression in CKD patients. However, there are limited data on safety and efficacy of antidepressant medications in patients with advanced CKD and ESRD. In addition, instituting effective treatment programs for depression in this patient population is challenging.20 Recently, attention has begun to be focused on a variety of treatment strategies that may show future promise in selected groups of patients. The purpose of the present manuscript is to review the available evidence on treatment of depression in CKD patients.

SCREENING FOR AND DIAGNOSIS OF DEPRESSION

Given the high prevalence of depression in CKD patients and the association of depression with poor outcomes and reduced health-related quality of life, it is suggested that depression screening be integrated into routine patient care. Screening can take place on initial presentation of CKD patients for evaluation in clinic, at dialysis initiation for ESRD patients, and perhaps 6 months after initiation, and yearly thereafter.3 Several studies validated commonly used depression screening self-report questionnaires against DSM IV-based structured interviews among patients with CKD and ESRD.3,11,21,22 Table 1 lists the screening characteristics of these questionnaires, which can generally be completed in a few minutes. Any of these validated scales can be used to screen patients in CKD clinic or dialysis facilities. As seen here, the cutoff scores with the best diagnostic accuracy for depressive disorder in patients with predialysis stage 2–5 CKD were similar to cutoffs used in the general population (Table 1).

Table 1.

Screening characteristics of self-report depression scales in CKD and ESRD

| Scale | No. of items | Score, range | Cutoff score in general population | Cutoff score in CKD (sensitivity, specificity) | Cutoff score in ESRD (sensitivity, specificity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI3,11,21,22 | 21 | 0–63 | ≥10 | ≥11 (89%, 88%) | ≥14–16 (62–91%, 81–86%) |

| QIDS-SR11 | 16 | 0–27 | ≥10 | ≥10 (91%, 88%) | |

| CESD3 | 20 | 0–60 | ≥16 | ≥18 (69%, 83%) | |

| PHQ21 | 9 | 0–27 | ≥10 | ≥10 (92%, 92%) |

Abbreviations: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CESD, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; QIDS-SR, 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report.

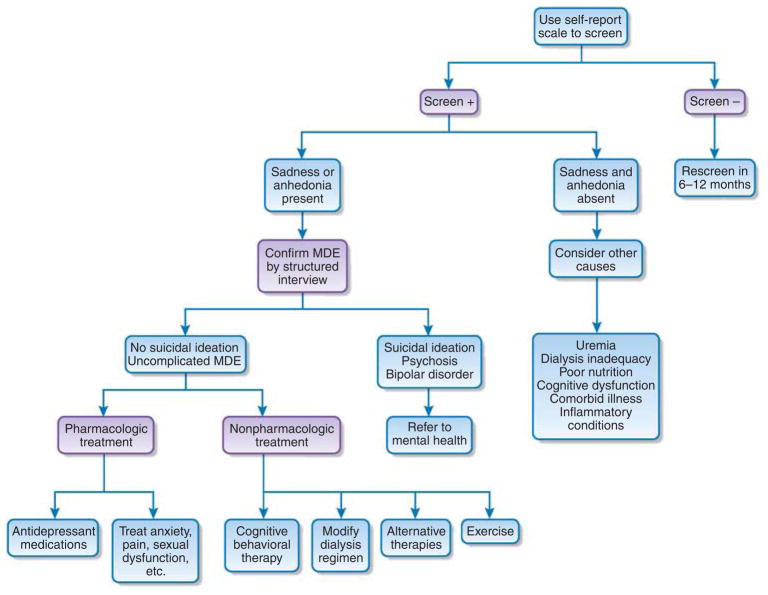

However, the cutoffs for those with ESRD were generally higher, perhaps because of more frequent presence of somatic symptoms in ESRD that may not be manifest in earlier CKD stages.11 Thus, somatic symptoms, such as fatigue, loss of energy, decreased appetite, sleep disturbance, and difficulty concentrating, suggestive of depressive affect, may be more commonly reported by ESRD patients.19,23–25 However, for a definitive diagnosis of depressive disorder based on DSM IV, either feelings of sadness (depressed mood) or loss of interest (anhedonia) must accompany these symptoms.2 If sadness or anhedonia is absent, consideration should be given to other causes such as dialysis inadequacy, poor nutritional status, cognitive dysfunction, dementia, and/or exacerbation of other comorbid illnesses, such as congestive heart failure (Figure 1). To help distinguish these symptoms, a structured interview should be performed to confirm a depressive disorder in patients who screen positive before treatment is considered. This can be performed by any of several individuals working in the clinic or dialysis facility (nephrologists or trained social workers and/or nurses).

Figure 1. Proposed algorithm for management of depression in patients with CKD and ESRD.

Alternative therapies include psychotherapy, counseling, social support, and music therapy. CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; MDE, major depressive episode.

Alternatively, referrals can be made to mental health professionals, if clinically indicated; but this approach may present logistical problems in terms of reimbursement issues and referral channels. Reasons to prompt referral to mental health include complicated depression such as with psychosis, clinical suspicion for other psychiatric diseases such as bipolar disorder, suicidal ideation, or treatment-resistant depression (Figure 1).

Paying attention to the presence of acute suicidal intent in depressed patients is particularly important in order to rule out immediate threat to themselves or others, and needs to be integrated into the patient evaluation.

TREATMENT ALGORITHMS

Once the diagnosis of clinical depression is made, treatment options need to be tailored to the individual needs of the patient and the resources available to the clinical team or dialysis facility (Figure 1). Thus, the care of each patient needs to be individually assessed and a treatment plan developed. There are a variety of treatment options available (discussed below), but few studies guide us as to the best evidence-based approach. In the following section, we review the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches to treating depression that have been suggested and studied in this patient population.

Pharmacologic intervention

Patients with moderate to advanced CKD and ESRD have generally been excluded from large antidepressant trials because of concerns for adverse events and the paucity of data on safety of antidepressants in this population.26 This likely has contributed to the undertreatment and underdosing of antidepressant medications in CKD patients. In fact, few studies have critically examined the pharmacologic treatment of depression in CKD patients.

Antidepressant medications are generally highly protein bound and not removed significantly by the dialysis procedure.27,28 They commonly undergo hepatic metabolism, but many have active metabolites that are renally excreted, leading to accumulation of potentially toxic metabolites in patients with decreased glomerular filtration rates.27,28 In addition, there is the risk of drug–drug interactions in CKD and ESRD patients who, because of a large burden of comorbidities and metabolic derangements, are already on many medications. Several classes of antidepressants such as serotonin modulators, tricyclics, and tetracyclics have cardiac side effects such as QTc prolongation, arrhythmias, and orthostatic hypotension (Table 2). Given that a large proportion of patients with CKD and ESRD suffer from cardiovascular (CV) disease, use of such medications without clinical trials to advocate safety must be carefully considered. Central nervous system depression is also a common adverse event. Increased bleeding risk was reported in association with serotonin-selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs),29 which may become problematic in advanced CKD and underlying platelet dysfunction related to uremia. Finally, the serotonergic gastrointestinal activity of SSRIs, one of the most commonly used antidepressant classes, can result in nausea and vomiting, which again may exacerbate these symptoms in patients with predialysis stage 5 CKD and ESRD.27,30

Table 2.

Antidepressant medication classes and dosing in CKD

| Medication class and dosing in normal eGFR | Dosing in CKD and ESRD | Potential class adverse effects32 |

|---|---|---|

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | ||

| Sertraline 50–200 mg/day, single dose | No dose adjustment recommended, but active metabolite is renally excreted | Increased risk of bleeding; GI symptoms including nausea and diarrhea; CNS effects; sexual dysfunction; hyponatremia |

| Paroxetine | ||

| Immediate-release 20–50 mg/day, single dose | Elimination half-life prolonged if CrCl <30 ml/min | |

| Controlled-release 25–62.5 mg/day, single dose | Immediate-release: 10 mg/day initial dose, max 40 mg/day Controlled-release: 12.5 mg/day initial dose, max 50 mg/day |

|

| Fluoxetine 20–80 mg/day, single dose | No dose adjustment recommended, but long half-life; use with caution | |

| Citalopram 20–40 mg/day, single dose | Initial dose 10 mg/day; active metabolite. Not recommended for eGFR <20 ml/min |

Higher citalopram doses associated with QTc prolongation, torsades de pointes |

| Escitalopram 10–20 mg/day, single dose | Use with caution in severe renal impairment | |

| Dopamine/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors | ||

| Bupropion 200 mg/day, 2 divided doses | Active metabolite; reduce frequency and/or dose | Accumulation of toxic metabolites; cardiac dysrhythmia; wide QRS complex; nausea, insomnia, dizziness |

| Max 450 mg/day, 3–4 divided doses | ||

| Noradrenergic and serotonergic agonist | ||

| Mirtazapine 15–45 mg/day at bedtime | Reduce dose; clearance reduced by 30% if CrCl 11–39 ml/min, and by 50% if CrCl <10 | CNS effects including somnolence; weight gain |

| Tricyclics and tetracyclics (TCAs) | ||

| Amitriptyline 75–150 mg/day, 1–3 divided doses | Generally avoid TCAs given cardiac side effects No dosage adjustment recommended |

QTc prolongation, arrhythmias, orthostatic hypotension; CNS and anticholinergic effects |

| Desipramine 100–300 mg/day, singly or divided | Caution advised if eGFR <15 ml/min; avoid given cardiac side effects | |

| Doxepin 25–300 mg/day, singly or divided | No dosage adjustment recommended | |

| Nortriptyline 25 mg/day, 3 to 4 times daily | No dosage adjustment recommended | |

| Max 150 mg/day | ||

| Serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors | ||

| Venlafaxine | ||

| Immediate-release 75–225 mg/day, 2–3 divided | Reduce dose by 25 to 50% in patients with mild-to-moderate renal impairment | Hypertension, sexual dysfunction, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, serotonin syndrome, accumulation of toxic metabolite O-desmethylvenlafaxine |

| Extended-release 37.5–225 mg/day, singly | ||

| Serotonin modulators | ||

| Nefazodone 100–600 mg/day, 2 divided doses | Generally avoid in cardiovascular or liver disease Increase dose carefully |

Cardiac dysrhythmias, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, liver failure, serotonin syndrome, priapism |

| Trazodone | ||

| Immediate-release 150–400 mg/day, divided | Increase dose carefully; use divided doses in elderly | |

| Extended-release 150–375 mg/day, singly at night | ||

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) | ||

| Phenelzine 45–90 mg/day, 3 divided doses | Avoid MAOI in CKD because of drug–drug interactions, although no dose adjustment advised for mild-to-moderate renal impairment | Significant drug–drug interactions; risk of hypertensive crisis with tyramine-rich foods; orthostatic hypotension |

| Selegiline transdermal patch, 6 mg per 24 h, may increase every 2 weeks by 3 mg per 24 h up to 12 mg per 24 h | ||

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; CNS, central nervous system; CrCl, creatinine clearance; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; GI, gastrointestinal.

Antidepressants increased the risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in children, adolescents, and young adults in short-term studies with major depressive disorder and other psychiatric disorders. Short-term studies did not show an increase in the risk of suicidality with antidepressants compared with placebo in adults beyond age 24 years, and there was a reduction in risk with antidepressants compared with placebo in adults aged ≥65 years.27

There are insufficient data to clearly suggest that treatment of major depressive disorder is either efficacious or changes outcomes in advanced CKD and ESRD patients.3,31,32 Few studies have examined this issue and are fraught with serious limitations including small sample sizes,33–37 lack of placebo control,32–35,37,38 and lack of DSM IV-based criteria for major depressive disorder.35,36,38 Nonrandomized observational studies of antidepressant medications in ESRD patients on chronic peritoneal dialysis reported some improvement in depressive symptoms;32,33 however, major limitations included the lack of a control group, selection and refusal bias, and a 50% medication discontinuation rate. A total of 136 patients with ESRD on chronic peritoneal dialysis who scored ≥11 on the BDI depression questionnaire were studied.32,33 Only 51% agreed to be further evaluated, and of those, only 72% agreed to have pharmacologic treatment. Finally, merely 23 of 44 (52%) of patients who agreed with treatment completed a 12-week course of antidepressant medications. Although a mean decrease in BDI scores from 17.1±6.9 to 8.6±3.2 was reported in completers, this study does underline the fact that even when ESRD patients were given a diagnosis of depression and treatment recommended, not all agreed to medical management.32,33

In another study, Atalay et al.39 reported that treatment with SSRI sertraline at 50 mg per day for 12 weeks was associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms in 25 chronic peritoneal dialysis patients, with BDI scores decreasing from 22.4 to 15.7 (P<0.001). Lack of a control group and small sample size were major limitations. In addition, mean posttreatment BDI score was still above the cutoff for depression. Koo et al.37 reported treatment of 34 dialysis patients with another SSRI, paroxetine, at 10 mg per day for 8 weeks concurrently with psychotherapy. Although the authors reported a statistically significant decrease in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores (from 16.6±7.0 to 15.1±6.6, P<0.01), the clinical relevance of 1.5 unit decrease in score is unclear. This study also suffered from the lack of a placebo-control group and short-term follow-up. Finally, a randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine treatment in 14 chronic HD patients with major depression revealed a statistically significant improvement in depression at 4 weeks that was not sustained at 8 weeks.36 No patients discontinued study drug because of adverse events, all of which were reported as minor. Furthermore, all patients in the intervention arm had serum plasma concentrations of fluoxetine and norfluoxetine <250 ng/ml at 8 weeks, similar to reported levels in patients with normal renal function. Although this study suggests promise for use of SSRIs in HD patients, the short duration and small sample size did not allow for adequate assessment of adverse effects.

Given the lack of data in CKD and ESRD patients, one might reflect on the antidepressant medication data that do exist in non-CKD patients, particularly those with CV disease. The association of depression with increased morbidity and mortality was also reported in non-kidney disease patients, especially in patients with CV disease.40,41 The Sertraline AntiDepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHART), a randomized, double-blinded placebo controlled trial, was conducted to assess the safety and efficacy of SSRI sertraline treatment in 369 patients with major depressive disorder after acute coronary syndrome.26 This trial documented efficacy and no evidence of CV harm for sertraline treatment initiated for an average of 34 days after acute coronary syndrome.26 Importantly, there were 20% fewer serious adverse CV events in the sertraline-treated group versus the placebo group, although this trend did not reach statistical significance.26 However, this study was not powered to assess CV events, and to confirm a 20% reduction in CV risk, a sample size of 4000 would have been required.

Unfortunately, patients with stage 3b–5 CKD and ESRD, which are precisely the groups at highest risk for CV morbidity and mortality, were excluded from SADHART because of safety concerns. The discouraging lack of data calls for large randomized placebo-controlled trials where CKD subjects are consecutively recruited and outcomes are blindly assessed. The Chronic Kidney Disease Antidepressant Sertraline Trial (CAST study) (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, clinical trials identifier number NCT00946998) is a double-blinded placebo-controlled trial presently recruiting participants to investigate whether treatment of a current major depressive episode with sertraline versus placebo improves depression severity and overall function and quality of life in patients with stage 3–5 predialysis CKD. Secondary outcomes include safety and tolerability.

Recommendations

Until more data are available for treatment of depression in CKD, nephrologists are left with the conundrum of adding another medication to the growing list prescribed to patients with advanced CKD or ESRD, considering nonpharmacologic therapy, or worse yet, dismissing depressive symptoms as nonspecific symptoms of chronic disease or uremia. However, data clearly suggest that both depression diagnosis and depressive symptoms independently prognosticate poor outcomes in these patients. Therefore, such symptoms should not be ignored.

Based on what data are available, if a trial of medication is considered, SSRIs would likely be a prudent choice because of established safety in patients with CV disease (Table 2). Table 2 lists the most common classes of antidepressant medications with specific drug examples, suggested dosing in renal impairment, and potential adverse effects. Once medication is initiated, response to treatment, need for dose adjustment, and the development of side effects should be monitored closely. This can be easily accomplished in ESRD patients given repeated encounters with health-care providers during routine presentation to the HD unit. The medication dose should not be escalated sooner than at intervals of at least 1 to 2 weeks, and only as tolerated. Special attention should be given to drug–drug interactions, as well as increased risk of suicidal ideation after initiation of antidepressant medications.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC INTERVENTIONS

Given the concerns and potential problems with pharmacologic treatment of depression in patients with advanced CKD and ESRD, potential nonpharmacologic interventions have been considered (Figure 1). These approaches, however, are likely to challenge health-care providers given the organization and structure of CKD and ESRD care in most countries (that is, the limited resources available for and limited recognition of the significance of providing psychosocial support). Importantly, several studies have now suggested an improvement in depressive symptoms in ESRD patients treated with various nonpharmacologic regimens, including alterations in the dialysis treatment regimen,42,43 exercise therapy,44,45 and cognitive behavioral therapy.46 In addition, consideration needs to be given to alternative approaches that have been used to treat depressed patients in the general population but which have not been systematically studied in CKD patients.47–49

Alterations in the dialysis treatment

Two recent trials have focused attention on the impact of alterations in the dialysis treatment regimen on depressive symptoms in HD patients.42,43 These studies lend support to previous work that observed a beneficial impact of more frequent HD on various health-related quality-of-life measures.50–52 First, the FREEDOM (Following Rehabilitation, Economics and Everyday-Dialysis Outcome Measurements) study is an observational cohort study of patients changing to six times per week HD with the NxStage machine with targeted standardized weekly KT/V of a minimum of 2.1.53 In all, 239 participants were enrolled (intention-to-treat cohort), but only 128 completed the study (per-protocol cohort). After conversion to six times per week HD, BDI scores decreased from baseline values of 11.2±0.8 to 7.4±0.6 at 4 months, and this improvement was sustained at 12 months (7.8±0.7; P<0.001), in the per-protocol analysis.42 The greatest improvement in depressive symptoms was noted in those with the highest baseline BDI scores, and those with scores ≥16 had a decrease in scores from 25±1 to 14.1±0.9 (P<0.001).42 However, the intention-to-treat analysis revealed less robust results, and BDI scores decreased from 12.8 to 10.7 (P<0.001). One criticism of this study was that percent prescribed antidepressant and anxiolytic medications also increased during the course of the study from 26 to 35% (P = 0.02). However, after adjustment for antidepressant use, the improvement in BDI scores remained statistically significant. Given the lack of a control group, the improvement in BDI scores may have occurred for reasons other than the intervention alone.

The Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) is a 12-month randomized trial comparing six times per week in-center HD with three times per week conventional HD.43 Standardized KT/Vs in the former group were 3.54±0.56 compared with 2.49±0.27 in the latter group. Significant improvements in the physical health composite score of the Short Form-36 (SF-36) health-related quality-of-life questionnaire were observed. BDI scores were lower in the six times per week HD patients, but the difference was not statistically significant.43

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a well-documented treatment option for patients with various psychiatric disorders.54 It is based on the premise that poor decisions, ineffective problem solving, and distorted or emotional thinking can result from ‘automatic thoughts’ in response to strong negative feelings and/or emotions. CBT uses well-structured techniques to support logical thinking and reorganize negative thoughts, behavior adjustments, and consequently mood status. In a recent 9-month randomized trial of CBT in Brazil, 85 HD patients with a major depressive disorder on standardized interviewing were randomized to receive standard care (control group) or CBT with a trained psychologist.46 Group sessions were held weekly for 12 weeks, and then monthly maintenance sessions were continued.46 Baseline BDI scores decreased from ~25 in both groups to 10.8±8.8 in the treatment group versus 17.6±11.2 in the control group (between-group comparison P<0.002) at 9 months. These significant improvements in depressive symptoms in the treatment group were confirmed with standardized patient interviews. Several domains on the KDQOL-SF (Kidney Disease Quality of Life questionnaire-Short Form) improved as well.

The benefit of CBT on a broader scale was observed in an interesting study of 69 ESRD patients in 22 dialysis units in Louisiana after hurricane-related trauma.55 Social workers were provided with training kits from the National Kidney Foundation using a cognitive behavioral framework. There was a significant amelioration of depressive symptoms in patients who participated in sessions as compared with patients who did not discuss the material with their social worker. Importantly, this study involved 22 social workers with limited but focused training, suggesting that more widespread use of CBT techniques may be promising in ESRD facilities and/or CKD clinics.56

The possible efficacy of combining antidepressant medications with CBT in CKD patients has not been explored in published studies.57 This is relevant as a large recent study involving 681 patients with chronic major depression showed that the response rate to medication or CBT alone was 48%, compared with a 73% response rate in patients receiving combined therapy.57 It would seem reasonable to explore trials involving combined approaches given the challenges presented in treating the CKD patient with depression.

Exercise training programs

The impaired physical functioning of ESRD patients is well documented, the causes of which are multifactorial.58 An association between physical functioning impairments and various health-related quality-of-life measures has been well established.59 Thus, recent studies suggesting a beneficial effect of exercise programs on depressive symptoms in ESRD are of interest.44,45 A randomized 2 × 2 factorial trial of anabolic steroid administration and resistance exercise training was conducted in 79 maintenance HD patients.60 Interventions included double-blinded weekly nandrolone decanoate or placebo injections and lower extremity resistance exercise training for 12 weeks during HD using ankle weights. Exercise was associated with an improvement in self-reported physical functioning on the Physical Functioning scale of the SF-36 (P = 0.03). In addition, there was a trend toward a reduction in fatigue in the groups that were assigned to exercise (P = 0.06). In another trial of HD patients with reduced aerobic capacity (measured as VO2 max (volume per time, oxygen, maximum)), 35 patients were randomized to a 10-month intradialytic exercise training program.44 There was a 21% increase in VO2 max in the exercise group and a 39% reduction in BDI scores—significantly different than in the control group, in whom there was no change in either exercise capacity or BDI scores.44 Finally, BDI scores decreased by 34.5% (P<0.001) in 24 HD patients randomized to a 1-year intradialytic exercise training program versus 20 patients randomized to control group.61 There was an inverse correlation between BDI scores and heart rate variability indices before and after exercise training, suggesting that decreased heart rate variability may play a mechanistic role in the association of depression with poor CV outcomes.

OTHER POTENTIAL APPROACHES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Among symptoms in ESRD patients, pain, sexual dysfunction, and anxiety are commonly encountered. A total of 44% of prevalent chronic HD patients were observed to have an anxiety disorder, and in 33% of those, the anxiety disorder persisted at 16 months.62 A strong association between anxiety and depressive symptoms was noted.62 Given this association, could the treatment of anxiety improve depressive symptoms in selected patients? The SMILE study (Symptom Management Involving End-Stage Renal Disease) is a multicenter, randomized trial comparing the effectiveness of two strategies (provider based vs. management intervention based) for treatment of symptoms in chronic HD patients.63 The primary outcome includes changes in scores on pain, erectile dysfunction, and depression scales.

Alternative interventions to treat depression in ESRD patients include addressing marital and family discord and barriers to social interactions. Marital and family tensions in ESRD patients are well documented, related at least in part to the stress of illness.64,55 These tensions have been associated with the presence of a depressive affect.64 Problems with social interactions of ESRD patients are also well documented and have been associated with poor outcomes.65 Involvement of community and religious organizations could be explored.65–67 Addressing the concerns of caregivers of patients with disabilities may also be helpful in relieving stress in difficult relationships.68

Other approaches used in non-ESRD samples to treat depression can be considered. A recent Cochrane analysis suggested that music therapy can have a beneficial impact on depressive symptoms.47 Importantly, patient acceptance of the therapy was high and dropout was low in all five studies critically examined. Furthermore, music therapy was shown to be beneficial in patients with a variety of chronic, advanced illnesses.48 Music and art therapy can take advantage, perhaps, of the length of time dialysis patients stay idle during the dialysis treatment.

Future directions could include exploring the possible association of depression with inflammation in CKD patients. Data suggest that the reduction in cytokine activation associated with inflammatory conditions alone without the concomitant administration of antidepressant medications can result in amelioration of depressive symptoms. For example, in 618 patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with etanercept, there was marked improvement in depressive symptoms, independent of an improvement in associated skin or joint problems.69

CONCLUSIONS

Patients with CKD suffer from a disproportionate burden of CV morbidity and mortality both before and after chronic dialysis initiation. However, interventions aimed at modifying risk factors associated with poor outcomes in these patients have not always translated into improved outcomes.70–73 In fact, some interventions, such as the use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in the TREAT trial, were associated with harm.73 Yet, as nephrologists, we spend hours during dialysis rounds in an attempt to fine-tune measures of anemia, dialysis adequacy, mineral metabolism, and dyslipidemia. Depression has now become a public health priority, and the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for depression if systems are in place to assure accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.9,74 It, therefore, becomes important to institute strategies to screen for and diagnose depression in CKD patients. What needs to be determined is whether or not treatments are efficacious and safe in this patient population, and then effective treatment algorithms need to be implemented. Importantly, the impact of treating depression on morbidity and mortality needs to be established. But, it must be emphasized that the successful amelioration of clinical depression and its symptoms may in and of itself be a valid therapeutic goal.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. This work was supported by VA MERIT grant CX000217-01 and NIH grant 1R01DK085512-01A1 awarded to Dr Hedayati. Support was also provided by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center O’Brien Kidney Research Core Center (P30DK079328).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

All the authors declared no competing interests.

References

- 1.Snow V, Lascher S, Mottur-Pilson C. Pharmacologic treatment of acute major depression and dysthymia. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:738–742. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-9-200005020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedayati SS, Bosworth HB, Kuchibhatla M, et al. The predictive value of self-report scales compared with physician diagnosis of depression in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1662–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedayati SS, Bosworth H, Briley L, et al. Death or hospitalization of patients on chronic hemodialysis is associated with a physician-based diagnosis of depression. Kidney Int. 2008;74:930–936. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hedayati SS, Grambow SC, Szczech LA, et al. Physician-diagnosed depression as a correlate of hospitalizations in patients receiving long-term hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:642–649. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimmel PL, Peterson RA, Weihs KL, et al. Multiple measurements of depression predict mortality in a longitudinal study of chronic hemodialysis outpatients. Kidney Int. 2000;57:2093–2098. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopes AA, Bragg J, Young E, et al. Depression as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization among hemodialysis patients in the United States and Europe. Kidney Int. 2002;62:199–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boulware LE, Liu Y, Fink NE, et al. Temporal relation among depression symptoms, cardiovascular disease events, and mortality in end-stage renal disease: contribution of reverse causality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:496–504. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00030505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedayati SS, Minhajuddin AT, Afshar M, et al. Association between major depressive episodes in patients with chronic kidney disease and initiation of dialysis, hospitalization, or death. JAMA. 2010;303:1946–1953. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedayati SS, Minhajuddin AT, Toto RD, et al. Validation of depression screening scales in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:433–439. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watnick S, Kirwin P, Mahnensmith R, et al. The prevalence and treatment of depression among patients starting dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:105–110. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, et al. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069–1078. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E, et al. Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1849–1856. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walters BA, Hays RD, Spritzer KL, et al. Health-related quality of life, depressive symptoms, anemia, and malnutrition at hemodialysis initiation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;40:1185–1194. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.36879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drayer RA, Piraino B, Reynolds CF, 3rd, et al. Characteristics of depression in hemodialysis patients: symptoms, quality of life and mortality risk. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng YS, Chiang CK, Hung KY, et al. The association of higher depressive symptoms and sexual dysfunction in male haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:857–861. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soykan A, Boztas H, Kutlay S, et al. Depression and its 6-month course in untreated hemodialysis patients: a preliminary prospective follow-up study in Turkey. Int J Behav Med. 2004;11:243–246. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1104_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopes AA, Albert JM, Young EW, et al. Screening for depression in hemodialysis patients: associations with diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes in the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2004;66:2047–2053. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer MJ, Kimmel PL, Greene T, et al. Socioeconomic factors contribute to the depressive affect among African Americans with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2010;77:1010–1019. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watnick S, Wang PL, Demadura T, et al. Validation of 2 depression screening tools in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:919–924. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Craven JL, Rodin GM, Littlefield C. The Beck Depression Inventory as a screening device for major depression in renal dialysis patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1988;18:365–374. doi: 10.2190/m1tx-v1ej-e43l-rklf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdel-Kader K, Unruh ML, Weisbord SD. Symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in chronic and end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1057–1064. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00430109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cukor D, Cohen SD, Peterson RA, et al. Psychosocial aspects of chronic disease: ESRD as a paradigmatic illness. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:3042–3055. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007030345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurella M, Luan J, Lash JP, et al. Self-assessed sleep quality in chronic kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol. 2005;37:159–165. doi: 10.1007/s11255-004-4654-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glassman AH, O’Connor CM, Califf RM, et al. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA. 2002;288:701–709. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Micromedex®Healthcare Series [intranet database]. Version 5.1. Thomson Healthcare; Greenwood Village, CO: [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen SD, Perkins V, Kimmel PL. Psychosocial issues in ESRD patients. In: Daugirdas J, Ing T, editors. Handbook of Dialysis. 4. Little Brown; Boston: 2007. pp. 455–461. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dalton SO, Johansen C, Mellemkjaer L. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of gastrointestinal bleeding: a population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:59–64. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen SD, Norris L, Acquaviva K, et al. Screening, diagnosis, and treatment of depression in patients with end-stage renal disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:1332–1342. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03951106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hedayati SS, Finkelstein FO. Epidemiology, diagnosis and management of depression in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:741–752. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wuerth D, Finkelstein SH, Finkelstein FO. The identification and treatment of depression in patients maintained on dialysis. Semin Dial. 2005;18:142–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.18213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wuerth D, Finkelstein SH, Ciarcia J, et al. Identification and treatment of depression in a cohort of patients maintained on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(05)80018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kennedy SH, Craven JL, Rodin GM. Major depression in renal dialysis patients: an open trial of antidepressant therapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 1989;50:60–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levy NB, Blumenfield M, Beasley CM, Jr, et al. Fluoxetine in depressed patients with renal failure and in depressed patients with normal kidney function. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:8–13. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(95)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blumenfield M, Levy NB, Spinowitz B, et al. Fluoxetine in depressed patients on dialysis. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27:71–80. doi: 10.2190/WQ33-M54T-XN7L-V8MX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koo JR, Yoon JY, Joo MH, et al. Treatment of depression and effect of antidepression treatment on nutritional status in chronic hemodialysis patients. Am J Med Sci. 2005;329:1–5. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turk S, Atalay H, Altintepe L, et al. Treatment with antidepressive drugs improved quality of life in chronic hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 2006;65:113–118. doi: 10.5414/cnp65113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Atalay H, Solak Y, Biyik Z, et al. Sertraline treatment is associated with an improvement in depression and health related quality of life in chronic peritoneal dialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42:527–536. doi: 10.1007/s11255-009-9686-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ariyo AA, Haan M, Tangen CM, et al. Depressive symptoms and risks of coronary heart disease and mortality in elderly Americans. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Circulation. 2000;102:1773–1779. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.15.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Talajic M, et al. Five-year risk of cardiac mortality in relation to initial severity and one-year changes in depression symptoms after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;105:1049–1053. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaber BL, Lee Y, Collins AJ, et al. Effect of daily hemodialysis on depressive symptoms and postdialysis recovery time: interim report from the FREEDOM study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:531–539. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chertow GM, Levin NW, Beck GJ, et al. In-center hemodialysis six times per week versus three times per week. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2287–2300. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ouzouni S, Kouidi E, Sioulis A, et al. Effects of intradialytic exercise training on health-related quality of life indices in haemodialysis patients. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:53–63. doi: 10.1177/0269215508096760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levendoglu F, Altintepe L, Okudan N, et al. A twelve week exercise program improves the psychological status, quality of life and work capacity in hemodialysis patients. J Nephrol. 2004;17:826–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duarte PS, Miyazaki MC, Blay SL, et al. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy is an effective treatment for major depression in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2009;76:414–421. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maratos AS, Gold C, et al. Music therapy for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD004517. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004517.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gallagher LM, Lagman R, Walsh D, et al. The clinical effects of music therapy in palliative medicine. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:859–866. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jakobsen JC, Hansen JL, Simonsen E, et al. The effect of adding psychodynamic therapy to antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder. A systematic review of randomized clinical trials with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses. J Affect Disord. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.035. e-pub ahead of print 27 April 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Finkelstein FO, Finkelstein SH, Wuerth D, et al. Effects of home hemodialysis on health-related quality of life measures. Semin Dial. 2007;20:265–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McFarlane PA. Nocturnal hemodialysis: effects on solute clearance, quality of life, and patient survival. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20:182–188. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283437046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suri RS, Garg AX, Chertow GM, et al. Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) randomized trials: study design. Kidney Int. 2007;71:349–359. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jaber BL, Finkelstein FO, Glickman J, et al. Scope and design of the FREEDOM study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;53:310–320. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beck AT. The current state of cognitive therapy: a 40-year retrospective. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steidl JH, Finkelstein FO, Wexler JP, et al. Medical condition, adherence to treatment regimens and family functioning. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37:1025–1027. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780220063006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weiner S, Kutner NG, Bowles T, et al. Improving psychosocial health in hemodialysis patients after a disaster. Soc Work Health Care. 2010;49:513–525. doi: 10.1080/00981380903212107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, et al. A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1462–1470. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Painter P. Determinants of exercise capacity in CKD patients treated with hemodialysis. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2009;16:437–448. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kutner N. Promoting functioning and well-being in older CKD patients: review of recent evidence. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008;40:1151–1158. doi: 10.1007/s11255-008-9469-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johansen KL, Painter PL, Sakkas GK, et al. Effects of resistance exercise training and nandrolone decanoate on body composition and muscle function among patients who receive hemodialysis: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2307–2314. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kouidi E, Karagiannis V, Grekas D, et al. Depression, heart rate variability, and exercise training in dialysis patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:160–167. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32833188c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cukor D, Cukor D, Coplan J, et al. Course of depression and anxiety diagnosis in patients treated with hemodialysis: a 16-month follow-up. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1752–1758. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01120308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weisbord SD, Shields AM, Mor MK, et al. Methodology of a randomized clinical trial of symptom management strategies in patients receiving chronic hemodialysis: the SMILE study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010;31:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Daneker B, Kimmel PL, Ranich T, et al. Depression and marital dissatisfaction with end-stage renal disease and their spouses. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:839–846. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.27704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cohen SD, Sharma T, Acuaviva K, et al. Social support and chronic kidney disease: an update. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007;14:335–344. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kimmel PL. Psychosocial factors in adult end-stage renal disease patients treated with hemodialysis: correlates and outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35(Suppl 1):S132–S140. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70240-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patel SS, Peterson RA, Kimmel PL. The impact of social support on end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2005;18:98–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.18203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gayomali C, Sutherland S, Finkelstein FO. The challenge for the caregiver of the patient with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Trans. 2008;23:3749–3751. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, et al. Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2006;367:29–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67763-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Suki WN, Zabaneh R, Cangiano JL, et al. Effects of sevelamer and calcium-based phosphate binders on mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2007;72:1130–1137. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wanner C, Krane V, März W, et al. Atorvastatin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:238–248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eknoyan G, Beck GJ, Cheung AK, et al. Effect of dialysis dose and membrane flux in maintenance dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:2010–2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pfeffer MA, Burdmann EA, Chen CY, et al. A trial of darbepoetin alfa in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2019–2031. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Larkin M. Depression screening may be warranted for adults, says U.S. task force. Lancet. 2002;359:1836. [Google Scholar]