Abstract

Several N-linked amino acid-linoleic acid conjugates were studied for their potential as anti inflammatory agents. The parent molecule, N-linoleoylglycine was tested in an in vivo model, the mouse peritonitis assay where it showed activity in reducing leukocyte migration at doses as low as 0.3 mg/kg when administered by mouth in safflower oil. Harvested peritoneal cells produced elevated levels of the inflammation- resolving eicosanoid 15-deoxy-Δ13,14-PGJ2. These results are similar to those obtained in earlier studies with N-arachidonoylglycine. An in vitro model using mouse macrophage RAW cells was used to evaluate a small group of structural analogs for their ability to stimulate 15-deoxy-Δ13,14-PGJ2 production. The D-alanine derivative was the most active while the D-phenylalanine showed almost no response. A high degree of stereo specificity was observed comparing the D and L alanine isomers; the latter being the less active. It was concluded that linoleic acid conjugates could provide suitable templates in a drug discovery program leading to novel agents for promoting the resolution of chronic inflammation.

Keywords: Elmiric acid, endocannabinoid, anti inflammatory, mouse peritonitis, prostaglandin

A class of lipoamino acids, long chain fatty acids covalently coupled to amino acids, which we have termed elmiric acids (EMA)1, 2, are emerging as an important family of endogenous signaling molecules 3 that act as physiological regulators of pain and inflammation4. The existence of these endogenous substances was first predicted in 1997 when synthetic examples were produced and shown to exhibit anti inflammatory and analgesic activity in mice5. Subsequent studies identified several naturally occurring EMAs in rat brain extracts 6. To date, about 50 naturally occurring members as well as several synthetic analogs of the EMA family have been identified15, 16, 2. Their actions include analgesia 4, 7, 8, anti-inflammatory effects 2, selective inhibition of cancer cell proliferation 9, vasodilation 10, cell migration11, 12 and calcium ion mobilization 13, 14.

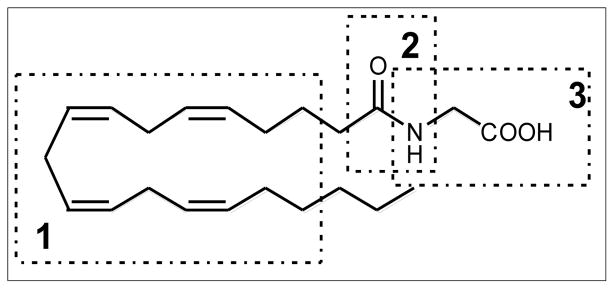

The prototypic EMA, N-arachidonylglycine (NAgly) shown in Figure 1, is found in rat brain, spinal cord, and other tissues where it occurs in amounts greater than the closely related endocannabinoid, anandamide4. Early reports4, 5, suggested that NAGly possessed analgesic properties but lacked the psychotropic activity of the cannabinoids. It has been shown that NAgly has low affinity for the cannabinoid CB1 receptor 17, however, it appears to activate the orphan G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR), GPR1814, 18. In this report, we have focused on lipoamino acids containing a linoleoyl residue for the purpose of discovering a template structure better suited toward the design of promising drug candidates (Figure 2). The simplest member of this series is N-linoleoylglycine (LINgly) or, using the elmiric acid system, EMA-1 (18:2). The notations used in this report are as follows: Amino acid EMA names are: Glycine, EMA-1; Alanine, EMA-2; Phenylalanine, EMA-9 and Tyrosine, EMA-10. Fatty acid abbreviations are: Palmitic, 16:0; Linoleic, 18:2; Arachidonic, 20:4, For a more complete list see reference 1.

Figure 1. The structure of NAgly.

There are three regions of the molecule that are of pharmacological interest. Region 1 confers a high degree of specificity of action. Polyunsaturated residues produce molecules with analgesic and anti- inflammatory action whereas saturated structures are inactive. Region 2 is related to metabolic stability since the EMAs are degraded by FAAH (fatty acid amide hydrolase) activity. Region 3, the amino acid residue, can modulate the analgesic/anti-inflammatory activities depending on steric factors and the chiral nature of the amino acid.

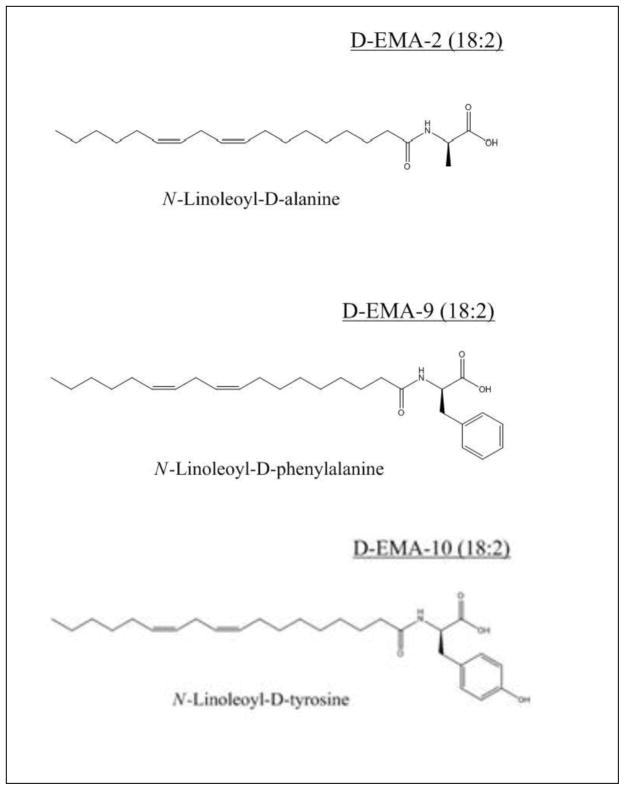

Figure 2.

Structures of the novel elmiric acids

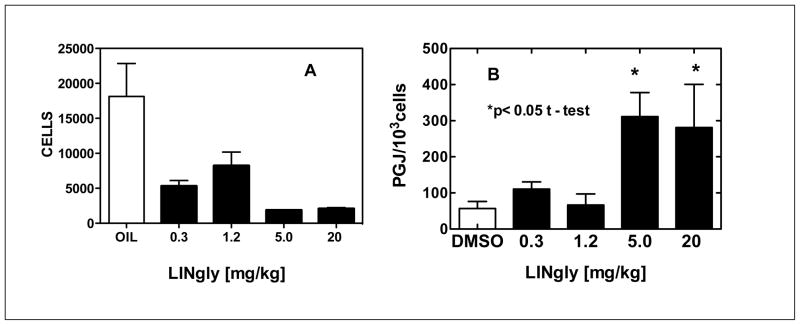

A widely used test for anti inflammatory action is the mouse peritonitis assay. This test is based on the migration of leukocytes into the peritoneal cavity following the injection of a pro inflammatory agent into the cavity. The inhibition of this migration is considered to be a measure of the anti inflammatory potential of a compound. Figure 3 Panel A shows the results obtained when LINgly24 at doses ranging from 0.3 to 20 mg/kg was subjected to this test. The values obtained suggest that the ED-50 is less than 0.3 mg/kg, which would make it a relatively potent anti inflammatory agent. Since it was administered orally, it is also indicative of its stability and good bioavailability. Thus the prototypic structure for this study, LINgly, appears to have been well chosen. The data shown in Panel B relates to a putative mechanism of action for the anti-inflammatory activity of LINgly and will be discussed in below.

Figure 3. N-linoleoylglycine inhibits leukocyte migration (A) and increases PGJ production (B) in the mouse peritonitis model.

A. The indicated treatments were administered by mouth and after 30 min, the mice were injected i.p. with 1 ml (sterile filtered) 8% BBL Fluid Thioglycollate Medium. Cells were harvested from the peritoneal cavity after 3 hours, exposed to lysing buffer for 2 minutes to remove erythrocytes, suspended in PBS/BSA and differential cell counts obtained. Control mice were given safflower oil. N=8.

B. Peritoneal cells were collected and maintained in culture fo 18 hrs. The media were then harvested and their PGJ levels measured by ELISA assay. N=4

Study A was carried out by BRM, Inc., (Worcester, MA). All animal studies were performed according to institutional, local, state, federal and NIH guidelines for the use of animals in research under Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee (IACUC)-approved protocols at BRM and The University of Massachusetts. Medical School.

Literature reports indicate that the elevations of tissue concentrations of PGJ are associated with the resolution of an inflammatory response19. This was suggested to come about through the binding and activation of the transcription factor PPAR-γ followed by increased expression of anti inflammatory factors. Our previous studies showed a positive correlation between PGJ levels and an anti inflammatory action of the EMAs in vivo 1. A robust stimulation of PGJ by LINgly was observed in RAW cells over a concentration range of 0.5 to 10 μM (Table 1). The response was comparable to that shown by NAgly indicating no sacrifice of potency when going from four to two double bonds and decreasing the chain length by two carbon atoms. However, earlier reports showed that the palmitoyl analog PALgly had no anti inflammatory effect either in vitro 1 or in vivo 18 representing a dramatic change with the saturated, shorter chain analog. This is in contrast to an earlier report that describes PALgly as a modulator of calcium influx and nitric oxide production in sensory neurons 20. An explanation for such differences could be related to the binding affinities of these EMAs to GPR18, however, these data are currently not available.

Table 1.

LINgly shows similar potency compared to NAgly in the RAW cell model.

| Treatment | Concentration (μM) | [PGJ] (pg/mL)a | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| LINgly | 0.5 | < 16.0 | - |

| LINgly | 1 | 177 | - |

| LINgly | 2.5 | 1843 | 431 |

| LINgly | 5 | 3907 | 293 |

| LINgly | 10 | 7315 | 1444 |

| NAgly | 1 | < 16.0 | - |

| NAgly | 10 | 6847 | 625 |

| DMSO | - | < 16.0 | - |

Cells were treated as in Figure 4. N=4

The available data allow some comments to be made on a possible mechanism for the anti inflammatory effects of the linoleoyl sub family of EMAs reported on here. In previous publications, we have proposed a putative mechanism of action involving the activation of the arachidonic acid cascade leading to an elevation of eicosanoid products 1, 2, 18, 21. The initial step is the stimulation of the release of free arachidonic acid that can then promote the synthesis of specific anti inflammatory eicosanoids such as PGJ and LXA4. How these eicosanoids bring about a resolution of chronic inflammation is uncertain and is a topic currently being studied19, 22, 23. A possible role for GPR18 in the EMA promoted release reaction should be considered.

Stereoisomeric preferences in a response are often an indication of receptor binding involvement in a particular response. Thus, we have compared the D and L enantiomers of N-linoleoylalanine in the PGJ model for anti inflammatory activity. The data shown in Table 2 indicate that there is, in fact, a considerable difference in activity with the D isomer being the more active. The decreases in cell count with increased drug are probably due to a decrease in proliferation rather than cell viability since we did not see many dead cells in the culture media. This high level of chiral preference suggests that a specific receptor may mediate the observed response. Again, based on our recent report 18, we would speculate that GPR18 is a likely mediator for this response.

Table 2.

Stereospecificity of EMA action in the RAW cell model.

| Treatmenta | Drug Concentration (μM) | Cell Count (% control) | PGJ (pg/ml) | PGJ/cell count | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-LINala | 0.3 | 136.0 | < 16.0 | - | - |

| D-LINala | 1 | 65.9 | 18.0 | 1186 | 0.08 |

| D-LINala | 3 | 33.9 | 233 | 7901 | 0.04 |

| D-LINala | 10 | 30.5 | 1580 | 48203 | 0.01 |

| L-LINala | 0.3 | 55.6 | < 16.0 | - | - |

| L-LINala | 1 | 74.3 | < 16.0 | - | - |

| L-LINala | 3 | 68.5 | < 16.0 | - | - |

| L-LINala | 10 | 55.5 | 30.3 | 1682 | 0.07 |

| DMSO | - | 100 | < 16.0 | - | - |

Cells were treated as in Figure 4. N=4

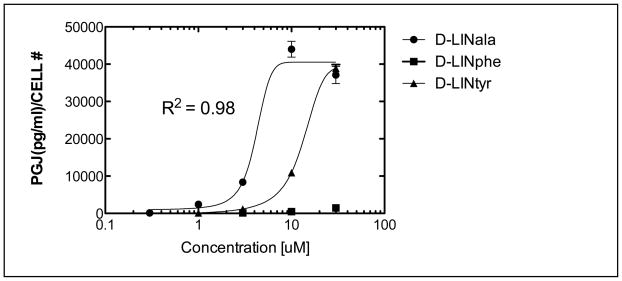

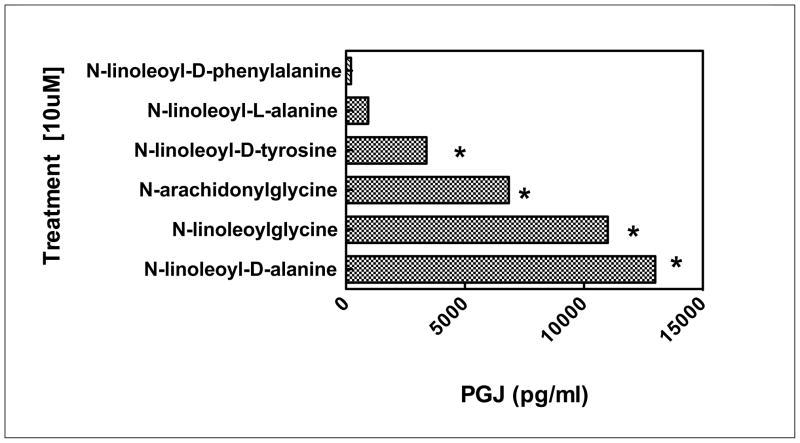

Figure 4 depicts a dramatic loss of activity when N-linoleoyl-D-phenylalanine (D-EMA-9(18:2)), and to a lesser extent N-linoleoyl-D-tyrosine, (D-EMA-10(18:2)) is substituted for N-linoleoyl-D-alanine (EMA-2 (18:2)). This could be attributed to steric volume increases or, possibly, to electronic effects. Further studies would be needed to distinguish between these possibilities.

Figure 4. Electronic and steric effects on PGJ responses in RAW cells.

Cells used were RAW264.7 and were obtained from ATCC. The base medium is Gibco DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum added. Cells are grown in a T-75 flask in 15 ml of medium; medium is replaced on day four and sub cultured on day seven. Cells are removed by scraping without the aid of trypsin. A sub cultivation ratio of 1:3 to 1:6 was used. Elisa assay kits for PGJ were obtained from Assay Designs, Inc., (Ann Arbor, MI). The identity of the PGJ analyte in the culture medium was confirmed by mass spectrometry (Wood and Makriyannis, unpublished data). Treatments were carried out in 48 well plates with 50,000 cells/500ul DMEM+FCS media/well and TNFα (10 nM) added. Cells were incubated for 20 hrs at 37°C and 5% CO2. Media were changed to 500ul of serum free DMEM, treated for 2 hrs and100 ul removed for assays. NAgly [10 μM] control; 16,300 pg/ml. DMSO control: <16.0 pg/ml. N=4

To summarize, a rank order (N-linoleoyl-D-alanine > N-linoleoylglycine > N-arachidonylglycine > N-linoleoyl-D-tyrosine > N-linoleoyl-L-alanine > N-linoleoyl-D-phenylalanine) of anti inflammatory action showing a complete range of responses was found even with the limited series of analogs studied in this report (Figure 5). Moreover, it may be concluded that linoleic acid analogs of NAgly can serve as lead molecules in a drug discovery program aimed at producing a stable and easily accessible drug candidate. By comparison, arachidonoyl derivatives are expensive and inherently less stable than linoleoyl derivatives and show a greater tendency to be non crystalline in nature

Figure 5. Estimated rank order responses in PGJ RAW cell model.

Cells were treated as in Figure 4. All values were obtained at 10uM concentrations of each EMA analog. Control: 1% DMSO vehicle. N=4

*ANOVA gave a p value of less than 0.05.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant number: DA-023635). Special thanks are due to Dr. Rao Rapaka, NIDA, whose steadfast support for this work is greatly appreciated. The authors are solely responsible for the contents of this article and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDA.

Abreviations

- EMA

elmiric acids

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- LXA4

lipoxin A4

- LINgly

N-linoleoylglycine

- LINphe

N-linoleoylphenylalanine

- LINtyr

N-linoleoyltyrosine

- NAgly

N-arachidonylglycine

- PALgly

palmitoylglycine

- PGJ

15-deoxy-Δ13,14-PGJ2

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Burstein S. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1259. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burstein SH, Adams JK, Bradshaw HB, Fraioli C, Rossetti RG, Salmonsen RA, Shaw JW, Walker JM, Zipkin RE, Zurier RB. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:3345. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradshaw HB, Walker JM. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:459. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang SM, Bisogno T, Petros TJ, Chang SY, Zavitsanos PA, Zipkin RE, Sivakumar R, Coop A, Maeda DY, De Petrocellis L, Burstein S, Di Marzo V, Walker JM. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107351200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burstein SMA, Pearson W, Rooney T, Yagen B, Zipkin R, Zurier A. Studies with analogs of anandamide and indomethacin. International Cannabinoid Research Society; Burlington, VT: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berdyshev EV, Schmid PC, Krebsbach RJ, Hillard CJ, Huang C, Chen N, Dong Z, Schmid HH. Biochem J. 2001;360:67. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3600067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeong HJ, Vandenberg RJ, Vaughan CW. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;161:925. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vuong LA, Mitchell VA, Vaughan CW. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:189. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burstein S, Salmonsen R. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:9644. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parmar N, Ho WS. Br J Pharmacol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00622.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McHugh D, Hu SS, Rimmerman N, Juknat A, Vogel Z, Walker JM, Bradshaw HB. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McHugh D, Page J, Dunn E, Bradshaw HB. Br J Pharmacol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ross HR, Gilmore AJ, Connor M. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:740. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohno M, Hasegawa H, Inoue A, Muraoka M, Miyazaki T, Oka K, Yasukawa M. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;347:827. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan B, O’Dell DK, Yu YW, Monn MF, Hughes HV, Burstein S, Walker JM. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:112. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900198-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan B, Bradshaw HB, Rimmerman N, Srinivasan H, Yu YW, Krey JF, Monn MF, Chen JS, Hu SS, Pickens SR, Walker JM. Aaps J. 2006;8:E461. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheskin T, Hanus L, Slager J, Vogel Z, Mechoulam R. J Med Chem. 1997;40:659. doi: 10.1021/jm960752x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burstein SMC, Ross A, Salmonsen R, Zurier RE. J Cell Biochem. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jcb.23245. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilroy DW, Colville-Nash PR, McMaster S, Sawatzky DA, Willoughby DA, Lawrence T. Faseb J. 2003;17:2269. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1162fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rimmerman N, Bradshaw HB, Hughes HV, Chen JS, Hu SS, McHugh D, Vefring E, Jahnsen JA, Thompson EL, Masuda K, Cravatt BF, Burstein S, Vasko MR, Prieto AL, O’Dell DK, Walker JM. Molecular Pharmacology. 2008;74:213. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.045997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burstein SH, Zurier RB. AAPS J. 2009;11:109. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilroy DW. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:524. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilroy DW, Lawrence T, Perretti M, Rossi AG. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:401. doi: 10.1038/nrd1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Materials. N-linoleoylglycine and N-linoleoyl-L-alanine and N-arachidonoylglycine were obtained from Medchem 101 (Conshohocken, PA). The other amide conjugates were synthesized according to published procedures (Burstein Sumner H, Zurier Robert B. Lipid-amino acid conjugates and methods of use. US 2006014820 A1 20060119 US Pat Appl Publ. 2006). All materials were obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification. For TLC, Silica Gel 60 F254 plates from Merck were used with detection by UV light or iodine vapor chamber. Acid chlorides were obtained from Nu-chek Prep, Inc. (Elysian, MN). Amino acids and esters were from Sigma-Aldridge. RAW cells were from ATCC.