Abstract

Fractures are reported to be the second most common findings in child abuse, after skin lesions such as bruises and contusions. This makes careful interpretation of childhood fractures in relation to the provided clinical history important. In this literature review, we address imaging techniques and the prevailing protocols as well as fractures, frequently seen in child abuse, and the differential diagnosis of these fractures. The use of a standardised protocol in radiological imaging is stressed, as adherence to the international guidelines has been consistently poor. As fractures are a relatively common finding in childhood and interpretation is sometimes difficult, involvement of a paediatric radiologist is important if not essential. Adherence to international guidelines necessitates review by experts and is therefore mandatory. As in all clinical differential diagnoses, liaison between paediatricians and paediatric radiologists in order to obtain additional clinical information or even better having joint review of radiological studies will improve diagnostic accuracy. It is fundamental to keep in mind that the diagnosis of child abuse can never be solely based on radiological imaging but always on a combination of clinical, investigative and social findings. The quality and interpretation, preferably by a paediatric radiologist, of radiographs is essential in reaching a correct diagnosis in cases of suspected child abuse.

Keywords: Child Abuse, Fractures, Radiology

Introduction

Fractures are reported to be the second most common findings in child abuse, after skin lesions such as bruises and contusions [39, 47]. Fractures resulting from physical violence can be found throughout the whole skeleton; they are likely to be multiple and can show diverse stadia of consolidation [21, 37, 53, 71]. In the majority of cases, no external physical findings, e.g. bruises or haematomas, are present [42, 66].

In the USA, approximately 10% of children under the age of 5 years visit the emergency department (ED) as a result of non-accidental injuries [22]. In children evaluated in the ED on suspicion of child abuse, over 30% appears to have fresh or healing fractures [23]. In a study on deceased children between the ages of 1 and 15 years (average, 3.9 years) of air force personnel in the USA, it was found that 55% of these children had been seen by a physician as a result of physical trauma in the month prior to their demise [38]. In a retrospective case based analysis of 435 child abuse victims, Carthy and Pierce found that in 51 children (11.7%), the diagnosis of child abuse could have been made at their first presentation at a hospital [9]. Of these 51 children, six (12%) died and ten (20%) survived with handicap.

Fractures in children, besides being a sign of child abuse, are a relatively common finding. In a large retrospective study in 8,642 children, the reported chance to sustain a fracture between birth and the age of 16 was 42% for boys and 27% for girls, i.e. an average 2.1% chance for a child to sustain one fracture per year [35]. These findings are in keeping with a similar study on fractures [71].

The fact that fractures on the one hand are a sign of child abuse but on the other hand are a quite common result of accidental trauma means that it is essential that the interpretation of the type and location of a fracture, seen in the light of the clinical anamnesis, is done by an experienced and trained (paediatric) radiologist [34, 36].

In this paper, we will discuss the radiological work-up in case of suspected child abuse and the main radiological findings indicative of child abuse. We will first address the different imaging techniques and then aspects of fractures (localisation, type, dating and differential diagnosis) that should be evaluated when considering the diagnosis of child abuse. As radiology deals with signs of physical child abuse child abuse should throughout the text be read as physical child abuse.

Imaging techniques

Conventional radiography

Conventional radiography has historically been and, to date, continuous to be the mainstay in radiological imaging of suspected child abuse, both in identifying new cases of possible child abuse, where an incidental finding on a radiograph can be the first sign of child abuse, as well as in the work-up of cases of suspected child abuse. In the latter, a skeletal survey, a systematically performed series of radiographic images that encompasses the entire skeleton, is a routine part of the work-up procedure in children under the age of 2 years [3]. In these cases, the skeletal survey should consist of a complete depiction of each anatomic region on separate radiographs. International guidelines for the skeletal survey have been published by the American College of Radiology (ACR) as well as the Royal College of Radiologists and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCR and RCPCH) (Table 1) [2, 65]. The main difference between these two guidelines is the addition of oblique chest radiographs in the RCR and RCPCH guideline. It has been shown that implementation of oblique chest radiographs increased the sensitivity for the detection of rib fractures by 17% (95%CI 2–36%) and the specificity by 7% (95%CI 2–13%) [24]. According to both protocols, a full skeletal survey consists of at least 20 radiographs. In our tertiary referral centre, where we review skeletal surveys in case of suspected child abuse, we have observed that it is quite common to perform an incomplete skeletal survey [67]. From this study, it was not clear if this is due to unfamiliarity with the international guidelines or fear for radiation dose. Especially when child abuse is part of the differential diagnosis, a thorough work-up is essential. Both making the diagnosis and missing the diagnosis can have enormous consequences for the lives of these children.

Table 1.

| ACR | RCR and RCPCH |

|---|---|

| Thorax (AP and lateral), to include ribs,a thoracic and upper lumbar spine | AP thorax, right and left oblique b views of the ribs |

| Pelvis (AP), to include the mid lumbar spine | Pelvis (AP) |

| Lumbosacral spine (lateral) | Lumbosacral spine (lateral) |

| Cervical spine (AP and lateral) | Cervical spine (lateral) |

| Skull (frontal and lateral), additional views if needed—oblique or Towne view | Skull (frontal and lateral), Towne view if occipital injury suspected |

| Humeri (AP) | Humeri (AP)c |

| Forearms (AP) | Forearms (AP) |

| Hands (PA) | Hands (PA) |

| Femora (AP) | Femora (AP) |

| Lower legs (AP) | Lower legs (AP) |

| Feet (PA) or (AP) | Feet (AP) |

aOblique views recommended, but not routine

bIn ’italics’ is the difference between guidelines

cLateral coned views of the elbows, wrists, knees and ankles may demonstrate metaphyseal injuries in greater detail. The consultant radiologist should decide this, at the time of checking the films with radiographers

In case of equivocal findings, the use of a repeat skeletal survey, in which case the skull should be excluded as fractures of the skull do not show callus formation, after 14 days, has shown to increase sensitivity and specificity. In a prospective study, additional information regarding skeletal trauma was obtained in 22 of 48 patients [75]. In two cases, the repeat skeletal survey exam influenced the diagnosis, and a definite diagnosis of child abuse could be made. In a retrospective study in 23 children, follow-up exams yielded additional information in 14 children [32].

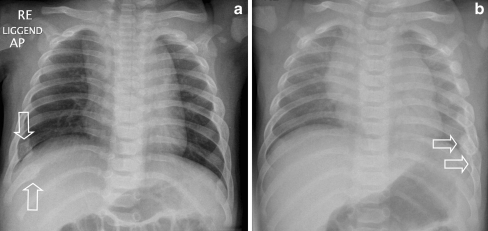

An issue not specifically addressed in the guidelines is the matter of how to deal with young siblings of abused children. In a study in 795 siblings of abused children, it has been shown that, in 37% of the children, maltreatment was not limited to the abused child but directed to all siblings; in 20% of the children, the abuse was specifically was directed at some but not all siblings [20]. These figures have made us decide that, in our hospital, siblings of abused children under the age of 2 years are routinely assessed for signs of child abuse in line with the international guideline cut-off age for skeletal survey (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a A 7-month-old child in whose twin rib fractures were seen on a chest radiograph (see b). Based on that finding, a full skeletal survey was performed on this child and rib fractures (arrows) were found. b A 7-month-old child with persistent signs of pneumonia. On a chest radiograph, performed to rule out pneumonia, incidental rib fractures (arrows) were found

Bone scintigraphy

In several countries, bone scintigraphy is used in cases of suspected child abuse. A meta-analysis found that although bone scintigraphy had a higher diagnostic yield in more anatomical complex locations, such as the pelvis and feet, it was less sensitive for classic metaphyseal lesions (CML) [11, 19, 26, 48, 62]. The latter has been shown by Mandelstam et al. [40], who, in 20 CMLs detected on conventional radiography, only seven showed increased uptake on the bone scintigraphy.

In the ACR appropriateness criteria, no consensus on the use of bone scintigraphy was reached by the expert panel. In the comments, it is stated: ‘Indicated when a clinical suspicion of abuse remains high and documentation is still necessary’ [57].

A drawback of bone scintigraphy is that not many departments have experience with (this technique in) children; this also means that the experience in reading these studies will be insufficient, thus limiting the applicability. Another relative drawback is the radiation dose involved in this study, which is significantly higher compared to the conventional skeletal survey (3 mSv compared to 0.16 mSv effective dose) [40].

Other imaging techniques

In the past few decades, the radiological arsenal has increased dramatically, and with the widespread availability of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), this specialty has evolved significantly.

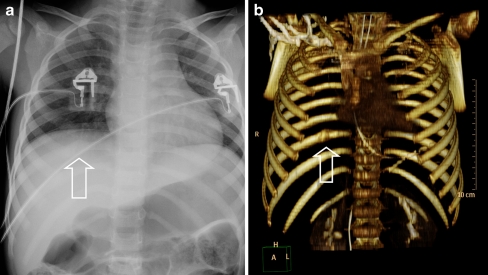

There is an increasing use of CT in first line trauma triage, where the ‘entry through the gantry’ is becoming more and more a reality [17, 73]. There is ample evidence that CT outperforms conventional radiology in, e.g. the detection of rib fractures [70]. In a retrospective study of 45 paediatric trauma patients, 18 of 45 patients had findings only at CT, including two patients with rib fractures [56]. An additional advantage of CT is the capability of obtaining 3D images, which can give more information (Fig. 2a, b). Given the relatively high radiation dose involved in computed tomography (an abdominal CT scan has a reported effective radiation dose of up to 10 mSv; for comparison, the radiation dose of a single chest radiograph is approximately 0.1 mSv) and the fact that CML will go undetected, its use in child abuse cases will be restricted to those critically ill children who might need (neuro)surgical intervention. CT should not be used as a replacement of conventional radiography; even in cases where CT has been performed during trauma evaluation, a full skeletal survey should be performed.

Fig. 2.

a Chest radiograph in a 3-year-old girl, victim of inflicted traumatic brain injury, who was admitted to the hospital in a comatose situation. A consolidating posterior rib fracture is shown (arrow). b Three-dimensional reconstruction of the chest CT (shaded surface display) clearly demonstrates the posterior rib fracture on the right side (arrow)

For an increasing number of clinical indications, bone scintigraphy is being replaced by whole body short tau inverse recovery MRI (WB-STIR) [27, 46]. This work has attracted attention to radiologists involved in the field of child abuse. In a study comparing the conventional skeletal survey to WB-STIR in 16 children (age range, 1.5–37 months), a sensitivity of 75% (33/44) for rib fractures and 67% (2/3) for metaphyseal corner fractures was found [15]. In a recent study by Perez-Rossello et al. [52], WB-STIR had a low sensitivity for CML (31%) and rib fractures (57%). Given these findings, the use of WB-STIR should not routinely be performed.

For the completeness of this overview of techniques, the use of ultrasonography and fluorine-18 sodium fluoride positron emission tomography should be mentioned. These techniques, on a case-by-case basis, have been reported but are not validated and should not be used in a routine work-up [14, 41, 49, 58].

Fractures

Differentiating between fractures resulting from accidental trauma or child abuse is, in most cases, only possible with knowledge of the full clinical history and in cooperation with attending clinicians. However, a list of specificity of fractures for child abuse has been published in the renowned textbook ‘Diagnostic imaging of child abuse’ edited by Kleinman (Table 2) [28]. Table 2 should be seen as a guideline, but it is important to remember that no fracture in itself is pathognomonic for child abuse (Fig. 3). In case of a fracture, with a high specificity of abuse, a differential diagnosis should always be considered. It is important that the fracture type matches the clinical history and developmental stage of the child.

Table 2.

Specificity of radiologic findings child abuse [28]

| Type and location of fracture | |

|---|---|

| High specificity | Classic metaphyseal lesions |

| Rib fractures, especially posterior | |

| Scapular fractures | |

| Spinous process fractures | |

| Sternal fractures | |

| Moderate specificity | Multiple fractures, especially bilateral |

| Fractures of different ages | |

| Epiphyseal separations | |

| Vertebral body fractures and subluxations | |

| Digital fractures | |

| Complex skull fractures | |

| Common but low specificity | Subperiosteal new bone formation |

| Clavicular fractures | |

| Long bone shaft fractures | |

| Linear skull fractures |

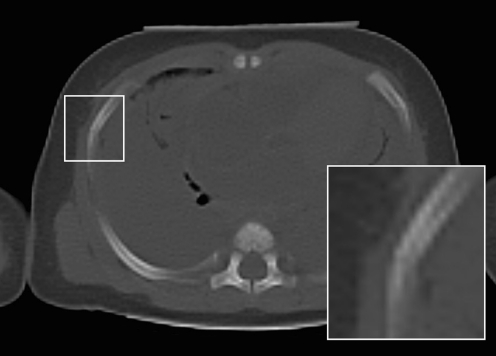

Fig. 3.

Rib fractures in a 10-week-old neonate. As the child has been admitted to the ward directly after birth;, child abuse was considered to be impossible. The fractures (see insert) were the result of osteopenia of prematurity

Two fractures, most indicative of child abuse, will be discussed in more detail.

Rib fractures

Rib fractures are generally seen as the hallmark of child abuse, especially in cases of inflicted traumatic brain injury. It is not uncommon that rib fractures are found incidentally as may be clinically silent (Fig. 1b) [10, 61]. The most common mechanism seen in case of rib fractures is anterior–posterior compression of the chest [31, 72]. In this situation, excessive leverage of the ribs over the transverse processes can lead to posterior rib fractures.

In a retrospective study, Barsness et al. [4] assessed the positive predictive value (PPV) of rib fractures in relation to child abuse. In total, 316 rib fractures were identified in 62 children; in 51 (82%), the fractures were due to abuse. In children <3 years of age, the PPV of rib fractures for abuse was 95%. Their study also showed that in child abuse cases, multiple rib fractures are more likely to be seen; posterior and lateral rib fractures (78%) were most prevalent, and 29% of the cases were the only skeletal finding.

Although rib fractures have a high specificity for abuse, they have been described in other scenarios. Posterior rib fractures, although rare and only in cases of difficult labour or large babies, have been reported after vaginal delivery [68]. Rib fractures are well described in metabolic bone disease of prematurity or other metabolic disorders and skeletal dysplasias [16, 59]. In these cases, rib fractures are seldom the only abnormal finding; family history, physical examination or the skeletal survey show indications for an underlying disorder or, e.g. vitamin D deficiency.

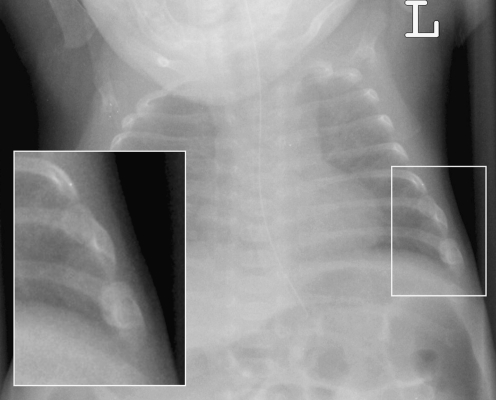

More controversially is the issue of rib fractures as a result of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), an issue often addressed by defence lawyers in court. Until recently, rib fractures were not thought to occur as a result of resuscitation [44, 60]. However, with the introduction of two handed infant encircling CPR, in which the hand position resembles the way perpetrators hold their children when they are reportedly shaken, it is becoming a relevant issue [1]. Several cases of anterior–lateral acute rib fractures as a result of resuscitation have been published (Fig. 4) [5, 13, 45, 69]. In all publications, the authors stress the fact that this is an extremely rare finding and that child abuse should be ruled out in all cases. Perhaps, even more important is the fact that even in cases in which rib fractures have been described as a result of CPR, no posterior rib fractures were seen.

Fig. 4.

Anterior rib fracture after CPR in an 8-week-old girl. Note that the fracture is located antero-lateral (see insert)

Metaphyseal corner fractures

Next to rib fractures, the CML, first described by the paediatric radiologist John Caffey in 1957, is a highly specific finding for abuse [8, 30]. These fractures are also known as corner or bucket handle fractures. CMLs are most often found in the distal femur, proximal and distal tibia/fibula and proximal humerus (Fig. 5a, b) [31]. On imaging, the appearance of CML varies depending on the size of the fragment and the position of the extremity in relation to the X-ray beam [29]. The mechanism of injury for the CML involves a shearing force in manual assaults; the extremities may undergo substantial torsion and traction leading to a CML. Healing of CML is variable. If the CML is associated with significant displacement and periosteal stripping, there may be conspicuous sclerosis and subperiosteal new bone formation. However, most CML heal without radiographic findings.

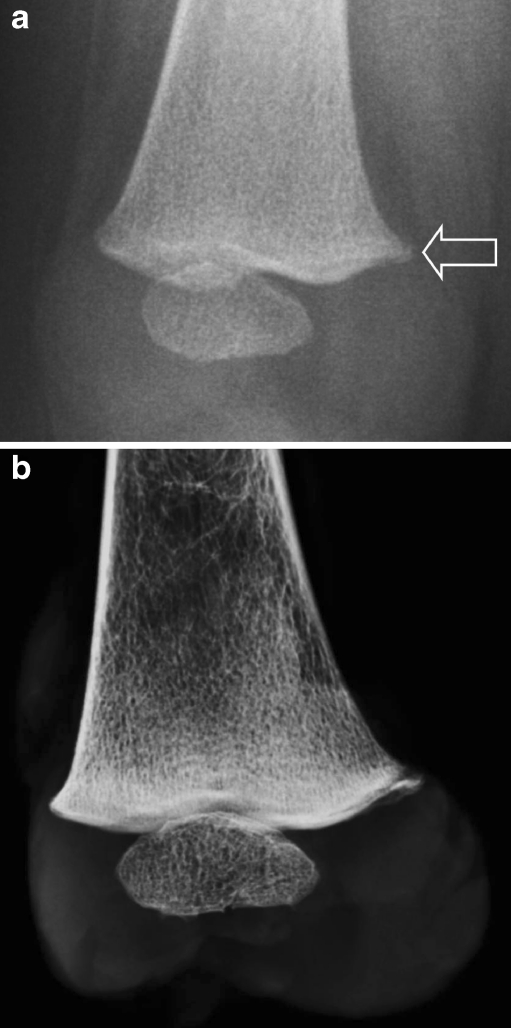

Fig. 5.

a Metaphyseal corner fracture in an 8-month-old child, who died as a result of blunt abdominal trauma. b At autopsy the femur was excised and imaged using a mammography system. The radiograph shows the metaphyseal corner fracture at the mediodorsal aspect of the distal right femur

Since no single fracture is pathognomonic for child abuse, there is a case for differential diagnosis for CML. CML have been described as an iatrogenic trauma after delivery and orthopaedic interventions for clubfeet [8, 18, 50]. In addition, metabolic bone diseases, e.g. rickets, and bone dysplasias, especially Schmid-type metaphyseal chondrodysplasia (OMIM no. 156500) and spondylometaphyseal dysplasia corner fracture type (OMIM no. 184255), can have metaphyseal changes similar to the CML.

Dating fractures

Radiological dating of fractures in the context of child protection, whether in a medical or in a forensic setting is possible to a certain extent but it certainly no exact science. Table 3 shows the radiological key findings most consistently agreed upon by radiologists [12, 25, 28, 74].

Table 3.

| Radiological findinga | Timing |

|---|---|

| Periosteal reaction | Minimum 1 week |

| Hard callusb | Minimum 2–3 weeks, peak 3–6 weeks |

| Signs of remodelling | Minimum 8 weeks |

aExcept fractures of the skull and classical metaphyseal lesions

bThe peak can be seen after 6 weeks as well

The issue of fracture dating was addressed in a meta-analysis of 1.556 papers, which were reviewed systematically by a large (and varying) group of specialists [54]. After application of exclusion criteria, only three studies, with combined data on 189 children, could be included. Based on this meta-analysis, the authors concluded that fracture dating in children is not an exact science, but that radiologists should be able to differentiate recent from old fractures.

We, as authors, feel that although estimation of fracture age should be approached with caution, experienced paediatric radiologists should be able to make informed judgments whether or not fractures (excluding skull, spine fractures and some CML) are in a healing phase. Healing can usually be judged as early or mature, and when multiple fractures are present, it is often possible to state if the fractures are of similar or different ages.

Differential diagnosis

As children grow up, they discover the world and accidents leading to fractures are therefore a common finding [43]. As a result of these accidents, long bone shaft fractures are the most common fractures in the emergency department. The older the child, the more likely this fracture is caused by an accidental trauma. In non-ambulatory infants, however, the same fractures are cause for concern. As the saying goes: ‘those who don’t cruise, don’t bruise’ [63].

In case of a paediatric fracture, a differential diagnosis should always be kept in mind, including child abuse. As mentioned in the introduction, about 10% of the paediatric ED visits is a result of child abuse [22]. It is known that this diagnosis is frequently missed by the treating physician due to an incomplete clinical work-up, both with respect to the physical exam as well as the anamnesis [55, 64]. Next to accidental trauma, the treating physician should think of child abuse, disorders related to collagen production, bone mineralisation and other diseases leading to an increased risk in bone fragility (Table 4). As mentioned previously, there are also diseases that may mimic fractures, such as skeletal dysplasias and also more common diseases such as osteomyelitis (Fig. 6) or sickle cell disease. Finally, especially for radiologists with a limited experience in paediatric radiology, normal variants, such as metaphyseal step-off’s, metaphyseal spurs and physiological subperiosteal new bone formation, may present as a diagnostic dilemma (Fig. 7). The interested reader is referred to textbooks for an in-depth discussion on the differential diagnosis of paediatric fractures [6].

Table 4.

Differential diagnosis in disease-related fractures

| Hereditary collagen disorders | Osteogenesis imperfecta |

| Menkes syndrome | |

| Osteogenesis imperfecta with congenital joint | |

| contractures (Bruck syndrome) | |

| Copper deficiency | |

| Genetic defects in bone mineralisation | Osteopetrosis |

| All forms of hypophosphataemic rickets | |

| Syndromatic hepatic ductular hypoplasia (Alagille syndrome) | |

| Secondary mineralisation disorders | Neuromuscular disorders |

| Nutritional rickets | |

| Cerebral palsy | |

| Malabsorption | |

| Metabolic bone disorders of prematurity | |

| Other at risk disorders | Muscular dystrophy |

| Spina bifida |

Fig. 6.

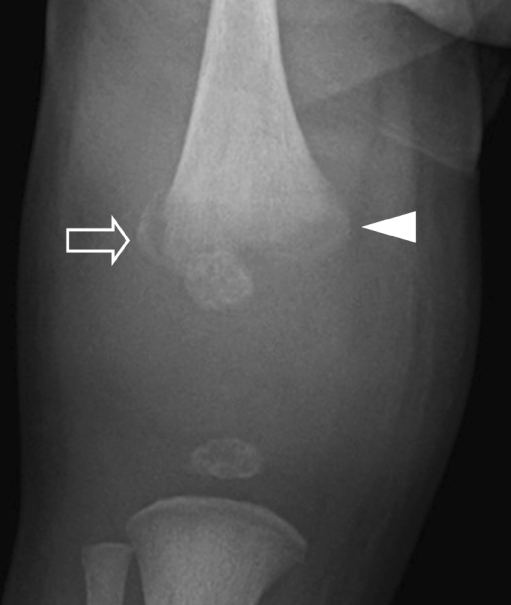

Two-week-old girl with a swollen knee; initially, the radiological findings were reported to be consistent with a CML. However, as she also had a slight fever and increased infection parameters, the diagnosis was reversed to osteomyelitis. The radiographic abnormalities improved quickly after the start of antibiotic therapy

Fig. 7.

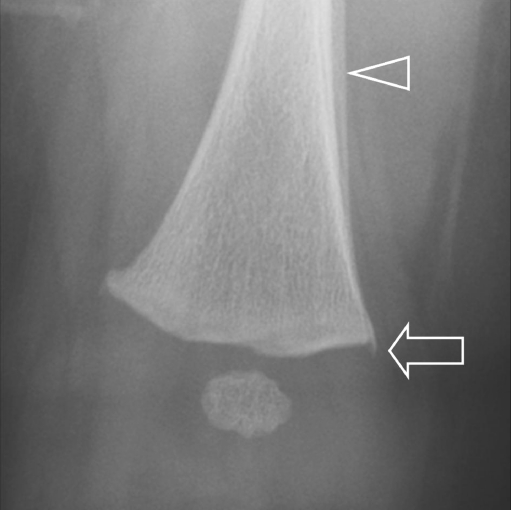

Radiograph of the distal right femur of a deceased 7-week-old girl, victim of inflicted traumatic brain injury, shows a metaphyseal spur (arrow) and subperiosteal new bone formation (arrowhead). Both are physiological findings at this age, which not seldomly are incorrectly interpreted as a pathological finding, i.e. metaphyseal corner fracture and a healing fracture

Discussion

Imaging child abuse is both clinically and emotionally difficult for those involved; this is one field in which an error in judgement in either way will have a detrimental effect on the overall health of the child and social system in which the child lives. That and the increasing public attention make it, in some countries, more and more difficult to find experts who are willing to be involved in this field.

Radiologists play an important if not vital role in the diagnosis of child abuse. In order to fulfil this role, several criteria must be met; first of all, the paediatric radiologist should be adequately trained in this field. In this light, it is of interest to note that the American Board of Pediatrics in 2005 established certification for child abuse paediatricians; for radiologists, such a certification does not exist [7]. Second, we feel that paediatric radiologists should be seen as equal partners to paediatricians involved in child abuse, similar to the development in radiology in general. Third, if at all possible paediatric radiologists should become involved in their hospital’s child abuse team, although this can be time consuming, their input will (as the first author can tell from personal experience) be highly appreciated. Finally, paediatric radiologists should set the standard in imaging child abuse and adhere to existing guidelines. Although the guidelines of the ACR and RCR and RCPCH are available online for free, adherence to these guidelines has shown to be poor [33, 51, 67]. In interpreting the results from these studies (especially European studies), it is of importance to note that paediatric radiology in general is a small subspecialty in radiology and that not all radiologists have been trained in paediatric radiology. Therefore, involvement of paediatricians in imaging of child abuse might have a positive influence on the adherence to these guidelines. In our country, as is the case in many European countries, most hospitals do not have direct access to a paediatric radiologist. We recommend that in case of suspected child abuse, the skeletal survey should be reviewed by a trained paediatric radiologist or a radiologist with experience in paediatric musculoskeletal imaging before a final conclusion is reported to parents or child protection services.

As in all clinical differential diagnoses, but perhaps even more important in child abuse cases, liaisons with paediatricians in order to obtain additional clinical information or even better having joint review of radiological studies will improve diagnostic accuracy. The diagnosis of child abuse is never solely based on radiological imaging but on a combination of clinical, investigative and social findings.

Acknowledgments

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- ED

Emergency department

- ACR

American College of Radiology

- RCR

Royal College of Radiologists

- RCPCH

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health

- CML

Classic metaphyseal lesions

- CPR

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- CT

Computed tomography

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- OMIM

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man

References

- 1.American College of Radiology (ACR) Standards for skeletal surveys in children. Resolution 22. Reston: American College of Radiology; 1997. pp. 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Radiology (ACR) (2006) ACR practice guideline for skeletal surveys in children. American College of Radiology, Reston, 17-6-0008

- 3.Barsness KA, Cha ES, Bensard DD, Calkins CM, Partrick DA, Karrer FM, Strain JD. The positive predictive value of rib fractures as an indicator of nonaccidental trauma in children. J Trauma. 2003;54:1107–1110. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000068992.01030.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betz P, Liebhardt E. Rib fractures in children—resuscitation or child abuse? Int J Leg Med. 1994;106:215–218. doi: 10.1007/BF01371340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bilo RAC, Robben SGF, van Rijn RR. Normal variants, congenital and acquired disorders. In: Bilo RAC, Robben SGF, van Rijn RR, editors. Forensic aspects of paediatric fractures; differentiating accidental trauma from child abuse. Berlin: Springer; 2009. pp. 133–170. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Block RW, Palusci VJ. Child abuse pediatrics: a new pediatric subspecialty. J Pediatr. 2006;148:711–712. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caffey J. Some traumatic lesions in growing bones other than fractures and dislocations: clinical and radiological features: The Mackenzie Davidson Memorial Lecture. Br J Radiol. 1957;30:225–238. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-30-353-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carty H, Pierce A. Non-accidental injury: a retrospective analysis of a large cohort. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:2919–2925. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1436-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapman S. Radiological aspects of non-accidental injury. J R Soc Med. 1990;83:67–71. doi: 10.1177/014107689008300204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conway JJ, Collins M, Tanz RR. The role of bone scintigraphy in detecting child abuse. Semin Nucl Med. 1993;23:321–333. doi: 10.1016/S0001-2998(05)80111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cumming W. Fractures of the hands and feet in child abuse: imaging and pathologic features. J Can Assoc Radiol. 1979;30:33. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dolinak D. Rib fractures in infants due to cardiopulmonary resuscitation efforts. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2007;28:107–110. doi: 10.1097/01.paf.0000257392.36528.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drubach LA, Sapp MV, Laffin S, Kleinman PK. Fluorine-18 NaF PET imaging of child abuse. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:776–779. doi: 10.1007/s00247-008-0885-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evangelista P, Barron C, Goldberg A, Jenny C, Tung G (2006) MRI STIR for the evaluation of nonaccidental trauma in children. In: Pediatric Academic Societies’ Abstract Archive 2000–2006, 2912.433

- 15.Feldman KW, Brewer DK. Child abuse, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and rib fractures. Pediatrics. 1984;73:339–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fung Kon Jin PH, Dijkgraaf MG, Alons CL et al (2011) Improving CT scan capabilities with a new trauma workflow concept: simulation of hospital logistics using different CT scanner scenarios. Eur J Radiol. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Grayev AM, Boal DK, Wallach DM, Segal LS. Metaphyseal fractures mimicking abuse during treatment for clubfoot. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:559–563. doi: 10.1007/s002470100497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haase GM, Ortiz VN, Sfanakis GN. The value of radionuclide bone scanning in the early recognition of deliberate child abuse. J Trauma. 1980;20:873–875. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198010000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton-Giachritsis CE, Browne KD. A retrospective study of risk to siblings in abusing families. J Fam Psychol. 2005;19:619–624. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hobbs CJ, Hanks HGI, Wynne JM. Child abuse and neglect—a clinician’s handbook. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holten JC, Friedman SB. Child abuse: early case finding in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 1968;42:128–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyden PW, Gallagher TA. Child abuse intervention in the emergency room. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1992;39:1053–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ingram JD, Connell J, Hay TC, Strain JD, Mackenzie T. Oblique radiographs of the chest in nonaccidental trauma. Emerg Radiol. 2000;7:42–46. doi: 10.1007/s101400050009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) consensus on science with treatment recommendations for pediatric and neonatal patients: pediatric basic and advanced life support. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e955–e977. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Islam O, Soboleski D, Symons S, Davidson LK, Ashworth MA, Babyn P. Development and duration of radiographic signs of bone healing in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:75–78. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.1.1750075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaudes PK. Comparison of radiography and radionuclide bone scanning in the detection of child abuse. Pediatrics. 1984;73:166–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kellenberger CJ, Epelman M, Miller SF, Babyn PS. Fast STIR whole-body MR imaging in children. Radiographics. 2004;24:1317–1330. doi: 10.1148/rg.245045048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleinman PK. Diagnostic imaging of child abuse. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleinman PK. Problems in the diagnosis of metaphyseal fractures. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:S388–S394. doi: 10.1007/s00247-008-0845-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleinman PL, Kleinman PK, Savageau JA. Suspected infant abuse: radiographic skeletal survey practices in pediatric health care facilities. Radiology. 2004;233:477–485. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2332031640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kleinman PK, Marks SC., Jr Relationship of the subperiostal bone collar to metaphyseal lesions in abused infants. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77A:1471–1476. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199510000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleinman PK, Marks SC, Jr, Nimkin K, Rayder SM, Kessler SC. Rib fractures in 31 abused infants: postmortem radiologic-histopathologic study. Radiology. 1996;200:807–810. doi: 10.1148/radiology.200.3.8756936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleinman PK, Nimkin K, Spevak MR, Rayder SM, Madansky DL, Shelton YA, Patterson MM. Follow-up skeletal surveys in suspected child abuse. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:893–896. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.4.8819377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kremer C, Racette S, Marton D, Sauvageau A. Radiographs interpretation by forensic pathologists: a word of warning. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2008;29:295–296. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0b013e3181847db0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landin LA. Fracture patterns in children. Analysis of 8, 682 fractures with special reference to incidence, etiology and secular changes in a Swedish urban population 1950–1979. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1983;202:1–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leung RS, Nwachuckwu C, Pervaiz A, Wallace C, Landes C, Offiah AC. Are UK radiologists satisfied with the training and support received in suspected child abuse? Clin Radiol. 2009;64:690–698. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leventhal JM, Thomas SA, Rosenfield NS, Markowitz RI. Fractures in young children. Distinguishing child abuse from unintentional injuries. Am J Dis Child. 1993;147:87–92. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1993.02160250089028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lucas DR, Wezner KC, Milner JS, McCanne TR, Harris IN, Monroe-Posey C, Nelson JP. Victim, perpetrator, family, and incident characteristics of infant and child homicide in the United States Air Force. Child Abuse Neglect. 2002;26:167–186. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maguire S, Mann MK, Sibert J, Kemp A. Are there patterns of bruising in childhood which are diagnostic or suggestive of abuse? A systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:182–186. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.044065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mandelstam SA, Cook D, Fitzgerald M, Ditchfield MR. Complementary use of radiological skeletal survey and bone scintigraphy in detection of bony injuries in suspected child abuse. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:387–390. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.5.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Markowitz RI, Hubbard AM, Harty MP, Bellah RD, Kessler A, Meyer JS. Sonography of the knee in normal and abused infants. Pediatr Radiol. 1993;23:264–267. doi: 10.1007/BF02010912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathew MO, Ramamohan N, Benet GC. Importance of bruising associated with paediatric fractures: prospective observational study. BMJ. 1998;317:1117–1118. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7166.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mathison DJ, Agrawal D. An update on the epidemiology of pediatric fractures. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26:594–603. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181eb838d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matshes EW, Lew EO. Do resuscitation-related injuries kill infants and children? Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2010;31:178–185. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0b013e3181df62ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matshes EW, Lew EO (2010) Two-handed cardiopulmonary resuscitation can cause rib fractures in infants. Am J Forensic Med Pathol (31):303–307 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Mazumdar A, Siegel MJ, Narra V, Luchtman-Jones L. Whole body fast inversion recovery MR imaging of small cell neoplasms in pediatric patients: a pilot study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1261–1266. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.5.1791261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McMahon P, Grossman W, Gaffney M, Stanitski C. Soft-tissue injury as an indication of child abuse. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1179–1183. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199508000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Merten DF, Radlowski MA, Leonidas JC. The abused child: a radiological reappraisal. Radiology. 1983;146:377–381. doi: 10.1148/radiology.146.2.6849085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nimkin K, Kleinman PK, Teeger S, Spevak MR. Distal humeral physeal injuries in child abuse: MR imaging and ultrasonography findings. Pediatr Radiol. 1995;25:562–565. doi: 10.1007/BF02015796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O'Connell A, Donoghue VB. Can classic metaphyseal lesions follow uncomplicated caesarean section? Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:488–491. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0445-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Offiah AC, Hall CM. Observational study of skeletal surveys in suspected non-accidental injury. Clin Radiol. 2003;58:702–705. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(03)00226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perez-Rossello JM, Connolly SA, Newton AW, Zou KH, Kleinman PK. Whole-body MRI in suspected infant abuse. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:744–750. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pierce MC, Bertocci GE. Fractures resulting from inflicted trauma: assessing injury and history compatibility. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2006;7:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cpem.2006.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prosser I, Maguire S, Harrison SK, Mann M, Sibert JR, Kemp AM. How old is this fracture? Radiologic dating of fractures in children: a systematic review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1282–1286. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.4.01841282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ravichandiran N, Schuh S, Bejuk M, Al-Harthy N, Shouldice M, Au H, Boutis K. Delayed identification of pediatric abuse-related fractures. Pediatrics. 2010;125:60–66. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Renton J, Kincaid S, Ehrlich PF. Should helical CT scanning of the thoracic cavity replace the conventional chest x-ray as a primary assessment tool in pediatric trauma? An efficacy and cost analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:793–797. doi: 10.1016/jpsu.2003.50169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Slovis TL, Smith W, Kushner DC, Babcock DS, Cohen HL, Gelfand MJ, Hernandez RJ, McAlister WH, Parker BR, Royal S, Strain JD, Strife JL, Kanda MB, Myer E, Decter RM, Moreland MS, Eggli D. Imaging the child with suspected physical abuse. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Radiology. 2000;215(Suppl: 805–9):805–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smeets AJ, Robben SG, Meradji M. Sonographically detected costo-chondral dislocation in an abused child. A new sonographic sign to the radiological spectrum of child abuse. Pediatr Radiol. 1990;20:566–567. doi: 10.1007/BF02011396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smurthwaite D, Wright N, Russell S, et al. How common are rib fractures in extremely low birth weight preterm infants? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;99:F138–F139. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.136853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spevak MR, Kleinman PK, Belanger PL, Richmond JM. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and rib fractures in infants. A postmortem radiologic–pathologic study. JAMA. 1994;272:617–618. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520080059044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stover B. Diagnostic imaging in child abuse. Radiologe. 2007;47:1037–1048. doi: 10.1007/s00117-007-1569-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sty JR, Starshak RJ. The role of bone scintigraphy in the evaluation of suspected child abuse. Radiology. 1983;146:369–375. doi: 10.1148/radiology.146.2.6217487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sugar NF, Taylor JA, Feldman KW. Bruises in infants and toddlers: those who don't cruise rarely bruise. Puget Sound Pediatric Research Network. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:399–403. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.4.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taitz J, Moran K, O'Meara M. Long bone fractures in children under 3 years of age: is abuse being missed in emergency department presentations? J Paediatr Child Health. 2004;40:170–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2004.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.The Royal College of Radiologists and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2008) Standards for radiological investigations of suspected non-accidental injury. RCR and RCPCH, London

- 66.Valvano T, Binns H, Flaherty E et al (2006) The reliability of bruising in predicting which fractures are caused by child abuse. In: Pediatric Academic Societies’ Abstract Archive 2000–2006, 3140.5

- 67.van Rijn RR, Bilo RA, Robben SG. Birth-related mid-posterior rib fractures in neonates: a report of three cases (and a possible fourth case) and a review of the literature. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39:30–34. doi: 10.1007/s00247-008-1035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van Rijn RR, Kieviet N, Hoekstra R, et al. Radiology in suspected non accidental injury: theory and practice in The Netherlands. Eur J Radiol. 2009;71:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weber MA, Risdon RA, Offiah AC, Malone M, Sebire NJ. Rib fractures identified at post-mortem examination in sudden unexpected deaths in infancy (SUDI) Forensic Sci Int. 2009;189:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wootton-Gorges SL, Stein-Wexler R, Walton JW, Rosas AJ, Coulter KP, Rogers KK. Comparison of computed tomography and chest radiography in the detection of rib fractures in abused infants. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32:659–663. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Worlock P, Stower M, Barbor P. Patterns of fractures in accidental and non-accidental injury in children: a comparative study. BMJ. 1986;293:100–102. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6539.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Worn MJ, Jones MD. Rib fractures in infancy: establishing the mechanisms of cause from the injuries—a literature review. Med Sci Law. 2007;47:200–212. doi: 10.1258/rsmmsl.47.3.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wurmb TE, Frühwald P, Hopfner W, Keil T, Kredel M, Brederlau J, Roewer N, Kuhnigk H. Whole-body multislice computed tomography as the first line diagnostic tool in patients with multiple injuries: the focus on time. J Trauma. 2009;66:658–665. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31817de3f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yeo LI, Reed MH. Staging of healing of femoral fractures in children. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1994;45:16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zimmerman S, Makoroff K, Care M, Thomas A, Shapiro R. Utility of follow-up skeletal surveys in suspected child physical abuse evaluations. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29:1075–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]