Abstract

Racism is a stressor that contributes to racial/ethnic disparities in mental and physical health and to variations in these outcomes within racial and ethnic minority groups. The aim of this paper is to identify and discuss key issues in the study of individual-level strategies for coping with interpersonal racism. We begin with a discussion of the ways in which racism acts as a stressor and requires the mobilization of coping resources. Next, we examine available models for describing and conceptualizing strategies for coping with racism. Third, we discuss three major forms of coping: racial identity development, social support seeking and anger suppression and expression. We examine empirical support for the role of these coping strategies in buffering the impact of racism on specific health-related outcomes, including mental health (i.e., specifically, self-reported psychological distress and depressive symptoms), self-reported physical health, resting blood pressure levels, and cardiovascular reactivity to stressors. Careful examination of the effectiveness of individual-level coping strategies can guide future interventions on both the individual and community levels.

Racism is a stressor that contributes to racial/ethnic disparities in mental and physical health and to variations in health outcomes within racial and ethnic minority groups (Anderson 1989; Clark et al. 1999; Mays et al. 2007; Paradies 2006; Williams and Williams-Morris 2000). Racism, in particular, self-reported ethnic or racial discrimination is a highly prevalent phenomenon. Members of most ethnic or racial minority groups report exposure over the course of their lifetime, and recent research indicates that episodes of ethnicity-related maltreatment occur on a weekly basis for some groups (Brondolo et al. 2009). The evidence points consistently to a relationship between self-reported racism and mental health impairments, specifically negative mood and depressive symptoms (Brondolo et al. 2008; Kessler Mickelson and Williams 1999; Paradies 2006). Some evidence has linked self-reported racism to hypertension and a more consistent body of evidence has linked racism to risk factors for hypertension and/or coronary heart disease (Brondolo et al. 2003, 2008; Harrell et al. 2003; Lewis et al. 2006; Peters 2004; Steffen and Bowden 2006). Racism has also been linked to several other health conditions (Paradies 2006), and to perceived health, which is itself a predictor of all-cause mortality (Borrell et al. 2007; Jackson et al. 1996; Schulz et al. 2006).

Since racism persists within the US, it is critical to identify the strategies individuals use to cope with this stressor and to evaluate the effectiveness of these strategies. As noted by Fischer & Shaw (1999), in 1996 the National Advisory Mental Health Council highlighted the importance of investigating individual-level factors that buffer the health effects of discrimination (Fischer and Shaw 1999). Although the knowledge base has grown since 1996, there is an ongoing need for greater understanding of the ways in which individuals can mitigate the health risks associated with racial/ethnic discrimination.

The aim of this paper is to identify and discuss key issues in the study of individual-level strategies for coping with interpersonal racism. It is important to note that we do not intend this review to communicate the idea that the burden of coping with racism should be placed on the shoulders of targeted individuals alone. Eliminating racism and the effects of racism on health will require interventions at all levels: from the individual to the family, community, and nation. Nonetheless, careful examination of the effectiveness of individual-level coping strategies is needed to guide future interventions at both the individual and other levels.

We begin with a discussion of the ways in which racism acts as a stressor and requires the mobilization of coping resources. Next, we examine available models for describing and conceptualizing strategies for coping with racism. Third, we discuss three major approaches to coping: racial identity development, social support seeking, and anger suppression and expression. These coping approaches have received sufficient research attention to permit a systematic review of evidence regarding their effectiveness for both mental and physical health outcomes. In addition, these coping approaches are intuitively plausible as potential buffers of the effects of racism on health, and if shown to be effective, would lend themselves to skills and information-based intervention approaches. We examine empirical support for the role of these coping approaches in buffering the impact of racism on mental health-related outcomes (i.e., specifically, self-reported psychological distress and depressive symptoms), self-reported physical health, resting blood pressure levels, and cardiovascular reactivity to stressors. These outcomes were chosen because they have been among those most consistently identified as correlates of racism (Paradies 2006). Finally, we discuss theoretical and methodological issues that are important to consider when conducting and evaluating research on strategies for coping with racism. Although much of the research on coping with racism has focused on African American samples, we have included the available data on other groups, including individuals of Asian and Latino(a) descent as well.

Definitions

Clark et al. (1999, p. 805) define racism as “the beliefs, attitudes, institutional arrangements, and acts that tend to denigrate individuals or groups because of phenotypic characteristics or ethnic group affiliation”. Contrada and others (2000, 2001) use the more general term ethnic discrimination to refer to unfair treatment received because of one’s ethnicity, where “ethnicity” refers to various grouping of individuals based on race or culture of origin. We consider racism a special form of social ostracism in which phenotypic or cultural characteristics are used to assign individuals to an outcast status, rendering them targets of social exclusion, harassment, and unfair treatment.

Racism exists at multiple levels, including interpersonal, environmental, institutional, and cultural (Harrell 2000; Jones 1997, 2000; Krieger 1999). However, the bulk of empirical research on coping with racism focuses on strategies for coping with interpersonal racism. Interpersonal racism has been defined by Krieger as “directly perceived discriminatory interactions between individuals whether in their institutional roles or as public and private individuals” (Krieger 1999, p. 301). Racism may have deleterious effects even when the target does not consciously perceive the maltreatment or attribute it to racism. However, this review considers the effectiveness of individual-level coping strategies employed to address episodes of racism that are both directly experienced and perceived. This focus on an interpersonal approach to examining racism is consistent with much recent work by Smith and colleagues examining the health effects of other psychosocial stressors (e.g., poverty) within an interpersonal context (see, for example, Gallo et al. 2006; Ruiz et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2003).

Types of ethnicity-related maltreatment

Racism/ethnic discrimination can encompass a wide range of acts including social exclusion, workplace discrimination, stigmatization, and physical threat and harassment (Brondolo et al. 2005a; Contrada et al. 2001). Social exclusion includes a variety of different interactions in which individuals are excluded from social interactions, rejected, or ignored because of their ethnicity or race. Stigmatization can include both verbal and non-verbal behavior directed at the targeted individual that communicates a message that demeans the targeted person (e.g., communicates the idea that the targeted individual must be lazy or stupid because he or she belongs to a particular racial or ethnic group). Workplace discrimination includes acts directed at individuals of a particular race or ethnicity that range from the expression of lowered expectations to a refusal to promote or hire. Threat and harassment can include potential or actual damage to an individual or his or her family or property because of ethnicity or race. Any of these discriminatory acts can be overt, such that the racial bias is made explicit (e.g., when accompanied by racial slurs), or the acts can be covert such that racial bias may not be directly stated but is implicit in the communication (Taylor and Grundy 1996).

Racism as a stressor

A number of conceptual models, including those which consider racism within stress and coping frameworks, have described the ways that racism may confer risk for health impairment (Anderson et al. 1989; Clark et al. 1999; Harrell et al. 1998; Krieger 1999; Mays et al. 2007; Outlaw 1993; Williams et al. 2003). In general, each model emphasizes the need to consider the acute effects of individual incidents of ethnicity-related maltreatment, as well as factors that sustain the damaging effects of these events. They highlight the importance of considering racism as a unique stressor, and as a factor that may interact with other potential race and non-race-related stressors, including low socioeconomic status and neighborhood crime. Racism itself and the environmental conditions associated with racism (e.g., neighborhood segregation) limit access to coping resources. The cumulative effects of acute and sustained stress exposure, combined with limited coping resources are likely to cause perturbations in neuroendocrine and autonomic systems that respond to acute stressors and that maintain or re-establish physiological homeostasis (Gallo and Matthews 2003; McEwen and Lasley 2003, 2007).

From the perspective of the targeted individual, racism is a complex stressor, requiring a range of different coping resources to manage both practical and emotional aspect of the stressor. Features of the racist incident, as well as the corresponding coping demands, may vary depending upon the physical, social, and temporal context of exposure. Targets must cope with the substance of racism, such as interpersonal conflict, blocked opportunities, and social exclusion. They must also manage the emotional consequences, including painful feelings of anger, nervousness, sadness, and hopelessness, and their physiological correlates. Targets may also need to manage their concerns about short and long term effects of racism on other members of their group, including their friends and family members. Indirect effects of racism (e.g., poverty, environmental toxin exposure, changes in family structure) may require additional coping efforts (Mays et al. 1996). A theme that may cut across and link many or even most of the coping tasks posed by racism is the management of damage to self-concept and social identity (Mellor 2004).

Episodes of ethnicity or race-based maltreatment can occur in a number of different venues. The effectiveness of the coping response may vary depending on the context in which the maltreatment occurs. Factors that may influence the choice and effectiveness of a coping strategy include variations in the intensity and nature of the threat, the perceived degree of intentionality of the perpetrator, the potential consequences of the act and of the coping response, the availability of resources to assist the target, and perceptions of the need to repeatedly muster different coping resources and the appraisal of one’s ability to do so (Richeson and Shelton 2007; Scott 2004; Scott and House 2005; Swim et al. 2003).

Different types of coping may be needed at different points in time: in anticipation of potential exposure to ethnicity-related maltreatment, at the time of exposure, following the episode, and when considering longer term implications of persistent or recurring exposure. The strategies that are effective for quickly terminating a specific episode of maltreatment are not necessarily the same as those needed to manage the possibility of longer term exposure. A variety of coping strategies may be needed at each point.

Consequently, one of the most serious challenges facing minority group members is the need to develop a broad range of racism-related coping responses to permit them to respond to different types of situations and to adjust the response depending on factors that might influence the effectiveness of any particular coping strategy. Targets must also develop the cognitive flexibility to implement an appropriate and effective strategy in each of the wide range of situations in which they may be exposed to discrimination, judge the relative costs and benefits of these strategies, and deploy them as needed over prolonged periods of time. This level of coping flexibility is beneficial, but difficult to achieve (Cheng 2003). The perception that one’s coping capacity is not adequate to meet the demands increases the likelihood that ethnicity-related maltreatment will be experienced as a chronic stressor.

Coping with racism: models and measures

There are a number of early models (Allport 1954; Harrell 1979) of the different strategies individuals used to respond to racism that have been reviewed in Mellor (2004). Some of the difficulties with these models are a function of more general problems with models of coping that have been well reviewed elsewhere (Skinner et al. 2003). Other concerns are more specific to the difficulties of developing models for coping with racism.

Most models fail to explicitly incorporate strategies designed to manage the interpersonal conflict associated with ethnicity-related maltreatment as well as with its emotional sequelae. They do not always include strategies both for coping with an acute event (i.e., responding to the perpetrator during episodes of ethnicity-related maltreatment) and for coping with the awareness that race-related maltreatment is likely to be an ongoing stressor. Additionally, it can also be difficult to determine if the coping strategies included in the models are intended to address racism specifically or the various consequences of discrimination, such as unemployment, denial of a job promotion, or poverty.

More recent work has utilized dimensions of coping that are more explicitly tied to theories of stress and coping, including problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, approach versus avoidance coping, and social support (Danoff-Burg et al. 2004; Scott 2004; Scott and House 2005; Thompson Sanders 2006). However, as Mellor (2004) points out, many of the strategies included in models of coping responses can only be loosely organized according to available rubrics for categorizing coping strategies. For example, it is unclear how to classify spirituality and Africultural coping, which appear to represent multifaceted strategies with some aspects involving problem-focused coping and others involving emotion-focused coping (Constantine et al. 2002; Lewis-Coles and Constantine 2006; Utsey et al. 2000a). There have been inconsistencies even within specific coping domains. For example, seeking social support when confronted by racism has been considered an approach coping strategy (Scott 2004; Scott and House 2005; Thompson Sanders 2006), a problem-focused coping strategy (Noh and Kaspar 2003; Plummer and Slane 1996), an emotion-focused strategy (such as when seeking emotional social support) (Tull et al. 2005), an avoidance strategy (if it involves venting, but no direct confrontation), and a strategy in an entirely separate category (Danoff-Burg et al. 2004; Swim et al. 2003; Utsey et al. 2000b).

Mellor (2004) suggests an alternate framework for organizing racism-related coping that focuses on the function of the coping strategies versus the content of their focus. His model highlights the importance of distinguishing between tasks that serve to prevent personal injury (e.g., denial, acceptance) from those that are intended to remediate, prevent, or punish racism (e.g., assertiveness, aggressive retaliation). This functional approach may be an important step toward developing more effective models of coping with racism, particularly if the purpose is closely linked to the various specific challenges that face targets of discrimination.

Measurement issues

The development of more comprehensive models is further limited by the small number of instruments available to assess racism-related coping. The Perceived Racism Scale (McNeilly et al. 1996) is one of the only instruments available to assess strategies for coping with racism. It is intended for use with African Americans and measures both exposure to experiences of ethnicity-related maltreatment and coping responses to the exposure. For each venue or domain in which racist events might occur (i.e., job-seeking, educational settings, the health-care system), participants are asked to indicate the cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses used to cope with each experience. Other researchers have used generic coping scales (e.g., the Ways of Coping or the Spielberger Anger Expression Inventory) and modified the presentation to inquire about coping in response to race-related maltreatment (e.g., Brondolo et al. 2005b).

Each of these measures is subject to the limitations of traditional self-reported trait coping indices (Lazarus 2000). It is difficult to evaluate the timing or circumstances in which the coping response is used. For example, when the Self-Report Coping Scale (Causey and Dubow 1992) is applied to the study of racism-coping (e.g., Scott and House 2005), participants indicate the degree to which they use strategies such as externalizing (i.e., getting mad or throwing things) as a response to race-related stress. It is unclear if the item refers to expressing anger at the perpetrator of the racist acts (possibly a problem-focused or approach coping strategy) or discharging anger later when thinking about specific incidents (possibly an emotion-focused coping strategy).

Careful delineation of the timing and function of the coping strategy is valuable, because there may be some strategies that are effective in the short run, but counterproductive if used persistently over time. For example, “keeping it to myself” may be a safe strategy to use as an immediate course of action in a situation in which the target may face immediate retaliation, but may be deleterious once the acute maltreatment has ended. Similarly, there may be strategies that are effective and acceptable in some settings, but not others. Measures which include items assessing both immediate and longer term responses and inquire about the circumstances of exposure to maltreatment are needed.

How do people cope with racism?

There are no population-based epidemiological data on the strategies most commonly used to cope with episodes of ethnicity-related maltreatment at the time of the event. There are very limited population-based data on the strategies used to manage discrimination in general. In a population-based sample of over 4,000 Black and White men and women, participants were asked about the ways they handled episodes of racial discrimination (Krieger and Sidney 1996). Most (69–78% depending on race and gender group) indicated they would “try to do something and talk to others.” Only 17–19% indicated that they would “accept it as a fact of life and talk to others.” Most individuals (86–97%) indicated that they would talk to others whether they took action in response to racism or accepted the racist behavior (Krieger and Sidney 1996). In contrast to the tendency of Black and White Americans to indicate that they would try to do something about racism, other research suggests that Asian immigrants in Canada would prefer to “regard it as a fact of life, avoid it or ignore it” (Noh et al. 1999). The ethnic and national differences in response suggest that the moderating effects of culture and immigration status on racism and coping must be further evaluated in larger ethnically diverse population-based studies.

Evaluating different coping approaches

In the next three sections, we review in detail the data on the effectiveness of three coping approaches that have been considered as responses to racism: racial identity development, social support seeking, and confrontation/anger coping. We restrict the reviews to published, peer-reviewed papers. For each topic area, studies for consideration were identified by accessing all major databases including PsychInfo, ERIC, MEDLINE, and Sociology Abstracts, using both ProQuest and EBSCO search engines. We included thesaurus terms racism, ethnic discrimination, racial discrimination, race discrimination, race-related stress. For a general review, we included the terms: coping, active coping, approach coping, stress-management. For the specific review on racial and ethnic identity, we included the terms: racial identity, ethnic identity, and racial socialization. For the section on social support, we included terms: support, social support, support coping, active coping, approach coping. For the section on anger, we included the terms: confrontation, anger, anger expression, anger suppression, anger management, anger-in, anger-out. We further searched the reference sections of each paper to identify additional studies. We also examined all published work of each author of each paper to determine if additional studies could be identified. Examining the empirical data on these three coping approaches highlights in specific detail some of the methodological issues involved in research investigating effective strategies for coping with racism.

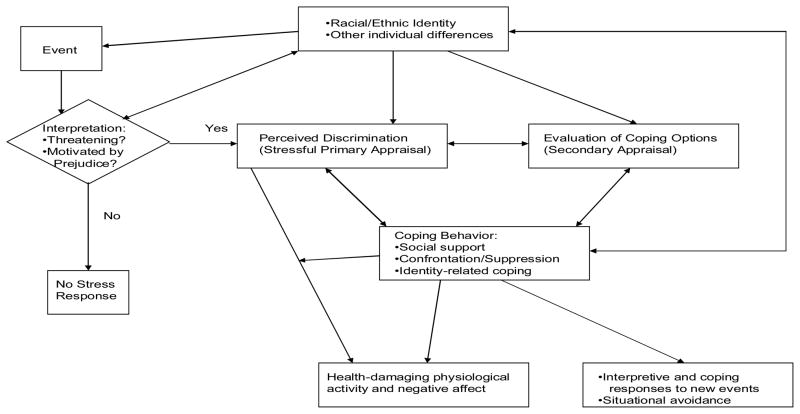

Our evaluation of coping effectiveness focuses on stress-buffering effects. A coping response may be said to buffer stress when, among individuals exposed to the stressor, those who engage in that response (or who engage in it to a greater degree) are less likely to experience a negative outcome than those who do not (or who engage in it to a lesser degree). The relative benefit associated with performing the coping response should be smaller or not at all in evidence among those who are not exposed to the stressor. It should be noted that stress-buffering is not the only manner in which a coping response might confer an advantage. Other models are plausible, including mediational models that describe a causal chain in which exposure to stress promotes performance of the coping response which, in turn, promotes more positive outcomes. However, a focus on stress-buffering is warranted since the aim of the paper is to identify those strategies which might be effective in ameliorating the health effects of exposure to racism, and could form the basis of coping-based interventions. Figure 1 provides a graphical illustration of these different possible pathways.

Figure 1.

Different pathways through which coping approaches may offset the effects of racism on mental and physical health.

Racial/ethnic identity as a buffer of the effects of racism on distress

Based on Phinney (1990, 1996), Cokley (2007, p. 225) defines ethnic identity as “the subjective sense of ethnic group membership that involves self-labeling, sense of belonging, preference for the group, positive evaluation of the ethnic group, ethnic knowledge, and involvement in ethnic group activities.” Similarly, racial identity has been defined as “a sense of group or collective identity based on one’s perception that he or she shares a common racial heritage with a particular racial group” (Helms 1990, p. 3). There are differences of opinion about the degree to which ethnic and racial identity represent distinct constructs (Cross and Strauss 1998; Helms 1990; Phinney and Ong 2007). Definitions of both constructs include a focus on shared history, values, and a common heritage. However, those who advocate the study of racial identity as a separate construct suggest that it entails a complex developmental process, reflecting the individual’s attempts to resolve the problems associated with racism directed both at the individual and at the group as a whole.

How could racial or ethnic identity serve as a coping strategy?

Racial and ethnic identity are generally considered individual difference variables, (i.e., an underlying set of schemas that help individuals make sense of and respond to their experiences as a member of their ethnic or racial group) (Cross and Strauss 1998; Helms 1990; Phinney and Ong 2007). However, researchers explicitly link the process of developing an ethnic identity to other acts that can have stress-buffering effects (Phinney et al. 2001). Some research explicitly frames ethnic identity as a variable possessing characteristics similar to other potential coping responses, capable of buffering the effects of stress exposure (see for example, Lee 2003). Despite the ambiguity about the degree to which racial identity can be considered within the domain of coping resources, research on racial identity has a potential impact on public health. If racial identity is mutable, and aspects of racial identity are effective in modifying psychological or psychophysiological responses to racism, those aspects of identity could be incorporated into health communications and could guide racial socialization practices.

Racial/ethnic identity may serve as a coping mechanism in several different ways. Specifically, some aspects of racism may influence the salience of race-related maltreatment and affect the subsequent appraisals of and coping responses to these events (Oyserman et al. 2003, Quintana 2007). A well-developed racial identity may be associated with historical and experiential knowledge about one’s own group and its social position. In turn this knowledge may help a targeted individual distinguish between actions directed at the person as an individual versus those directed at the person as a member of a particular group (Cross 2005). This can protect targeted individuals from injuries to self-esteem or distress when they are exposed to negative events that may be a function of ethnic discrimination rather than individual characteristics of behavior (Branscombe et al. 1999; Mossakowski 2003; Sellers and Shelton 2003). Racial socialization could provide an individual with an opportunity to consider possible approaches to this maltreatment and could serve to expedite the implementation of coping responses (Hughes et al. 2006). Ethnic connection and belonging could ameliorate some of the pain of ostracism from other groups.

Appreciating the potential benefits of a well-developed sense of ethnic or racial identity, investigators have generated a large body of research that has examined the nature of racial and ethnic identity, and a smaller body of research that has tested the hypothesis that a strong positive racial or ethnic identity might buffer the effects of racism on mental health/psychological distress. However, the findings to date have been conflicted and present a number of methodological problems that need resolution.

Our review identified 12 published peer-reviewed papers that explicitly tested the hypothesis that ethnic or racial identity buffers the effects of exposure to racism on psychological distress or depression (Banks and KohnWood 2007; Bynum et al. 2007; Fischer and Shaw 1999; Greene et al. 2006; Lee 2003, 2005; Mossakowski 2003; Noh et al. 1999; Sellers et al. 2003, 2006; Sellers and Shelton 2003; Wong et al. 2003). Details of the studies, including the samples, measures, and results, are presented in Table 1. The effects of ethnic identity as a buffer of the relationship of racism to depressive symptoms or psychological distress were tested in samples of African Americans, Filipinos, Koreans, South Asian Indians, and Latino(a)s, with most, but not all, studies employing samples of convenience.

Table I.

Studies of the buffering effects of racial identity on the relationship of racism to mental physical health indices

| Authors/Date | Sample | Racial Identity | Measures Racism | Psychological Distress | Design | Main effects of racial identity on depressive sx/distressa | Buffering effects of racial identity on the relationship of racism to depress sx/distressb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banks & Kohn-Wood (2007) | 194 AA college students, convenience sample | MIBI – 7 subscales scores used to form 4 clusters: Integrationist Multicultural Race-focused Undifferentiated |

RaLES Daily Exper. | CES-D | Correlational, cross-sectional | (NO) Integrationist (NO) Multicultural (NO) Race-focused (NO) Undifferentiated |

(YES - I) Integrationist/RaLES Daily Exper./CES-D |

| Bynum, Burton & Best (2007) | 247 AA college students, convenience sample | TERS - Cultural Pride Cultural Coping with Antagonism |

RaLES Brief Racism | BSI | Correlational, cross sectional | (YES-POS) Cultural Pride (YES-NEG) Cultural Coping with Antagonism |

(NO) Cultural Pride/SRE/BSI (NO) Cultural coping with antagonism/SRE/BSI |

| Fischer & Shaw (1999) | 119 AA college students, convenience sample |

Beliefs: SORS-Racism Awareness Teaching Experiences: TERS – Racism Struggles Scale |

SRE | MHI | Correlational, Cross- sectional | (NO) SORS (NO) TERS |

(NO) SORS/SRE/MHI (YES- B) TERS/SRE/MHI |

| Green, Way, Pahl (2006) | 136 racially diverse high school students, convenience sample | MEIM EI-achievement EI-affirmation |

Discrim. by Adults (Way, 1997) Discrim. by Peers (Way, 1997) |

Children’s Depression Inventory (Kovacs, 1985) | Correlational, Prospective Design | (YES-POS) EI – Achievement (YES-POS) EI- Affirmation |

(NO) EI-Achievement/discrim./depressive sx (NO) EI-Affirmation/discrim./depressive sx |

| Lee (2003) (Study 2) | 67 Asians of Indian descent young adults, convenience sample | MEIM | PDS | CES-D | Correlational, cross sectional | (NO) EI | (NO) EI/PDS CES-D |

| Lee (2005) | 84 Korean college students | MEIM – 4 factors EI-Clarity EI-Pride EI-Engagement EI-Other |

PDS | CES-D | Correlational, cross sectional | (YES-POS) EI- Clarity (YES-POS) EI- Pride (YES-POS) EI- Engagement |

(YES - I) Pride/PDS/CES- D |

| Mossakowski (2003) | 2109 Filipino adults, population- based sample | MEIM | Major discrim. (1 item) Everyday discrim. (Williams et al., 1997) |

SCL-90R | Correlational, cross sectional | (YES-POS) EI | (YES - D) EI/major lifetime discrim./depressive sx (NO) EI/everyday discrim./depressive sx |

| Noh, Beiser, Kaspar, Hou & Rummen (1999) | 647 Asian immigrants (43% Chinese) Population- based sample | Study-specific measure of ethnic identification composed of questions about: Salience, intermarriage, language retention, ethnic identification | Study-specific measure: single item experienced discrimination based on race | Depression- related symptoms, 17 items | Correlational, cross sectional | (NO) Ethnic identification | (YES - I) Ethnic identification/discrim./depressive sx |

| Sellers & Shelton (2003) | 349 AA college students, convenience sample | MIBI Centrality Private regard Public regard Ideology subscales (Nationalist, Oppressed Minority, Assimilation, Humanist) |

DLE | CES-D, STAI PSS Psych. Distress (composite of all three- labeled psychological distress) | Correlation, Prospective, but also cross sectional analyses | (YES-POS) Private regard (YES-POS) Public regard |

(YES - B) Nationalist identity/DLE/depressive sx |

| Sellers, Caldwell, Schmeelk-Cone, & Zimmerman (2003) | 555 AA young adults (mean age = 17), convenience sample | MIBI Centrality Public Regard |

20 race-related hassles (based on Harrell, 1997) | SCL-90-R depression and anxiety combined | Prospective, correlational, SEM | (YES-POS) Public regard (YES-POS) Centrality |

(NO) Centrality/race- related hassles/anxiety and depressive sx (NO) Public Regard/race- related hassles/anxiety and depressive sx |

| Sellers, Linder, Martin, & Lewis (2006) | 314 AA youth (11–17 years), convenience sample | MIBI Centrality Private regard Public regard |

DLE – frequency only | CES-D | Correlational cross-sectional | (YES-POS) Private regard | (YES-I) Public regard/DLE/CES-D |

| Wong, Eccles, & Sameroff (2003) | 629 AA high school students, volunteers, comvenience sample | Inventory for this study to measure EI, including close relationship to ethnicity, sense of rich heritage, pride and belonging and feeling supported by others in ethnicity | Teacher discrimination, Peer discrimination (everyday maltreatment type items) | CES-D | Correlational, prospective and cross sectional analyses | (NO) EI | (NO) EI/teacher discrim./CES-D (NO) EI/peer discrim./CES-D |

Note. AA = African American; MH = mental health; sx = symptoms; discrim. = discrimination; EI = ethnic identity. MIBI = Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998). RaLES Daily Exper. = Daily Life Experiences subscale from the Racism and Life Experience Scales (Harrell, 1997). CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977). TERS = Teenager Experience with Racial Socialization Scale (Stevenson et al., 2002). BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory (Deragotis & Melisarotis, 1983). PSS = Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen & Williamson, 1988). RaLES-R - Brief Racism Scale = Brief Racism Scale from the Racism and Life Experiences Scales-Revised (Harrell, 1997a, 1997b). SORS-A = Scale of Racial Socialization for Adolescents (Stevenson, 1994). SRE = Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996). MHI = Mental Health Inventory (Veit & Ware, 1983). MEIM = Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (Phinney, 1992); EI = ethnic identity. PDS = Perceived Personal Ethnic Discrimination (Finch et al., 2000). SCL-90 = Symptom Checklist – 90 – Revised (Deragotis, 1994). DLE = Daily Life Experience subscale of the Racism and Life Experience scales (Harrell, 1994). STAI = State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, 1983).

For each main effect tested, the component of racial identity evaluated is listed. The results are categorized as follows: (NO) = No significant main effect; (YES-POS) = Significant main effect such that increasing scores on listed components of racial identity are associated with lower symptom reports; (YES-NEG) = Significant main effects such that increasing scores on listed components of racial identity are associated with greater symptom reports.

For each interaction action tested, the variables are presented as follows: measure of racial identity/measure of racism/measure of depressive symptoms or distress. The results are categorized as follows: (NO) = No significant interaction (buffering) effect; (YES-I) = Significant interaction effect, such that the relationship of racism to symptoms is stronger for those with high scores on listed components of racial identity; (YES-B) = Significant interaction effect, such that the relationship of racism to symptoms is weaker for those with high scores on listed components of racial identity. In this case, racial identity serves as a buffer.

These studies assessed different aspects of ethnic or racial identity and used several different strategies for measuring these dimensions. Some investigators used measures of pride or belonging, including the Multi-Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Phinney 1992) or the private regard subscale of the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI; Sellers et al. 1997). Other investigations included measures of racial centrality, a construct involving the degree to which one’s race or ethnicity forms an important part of self-concept (Sellers et al. 1997). Still other studies included aspects of racial identity that refer to the development of preparation for discrimination, including measures of racial socialization. Three studies (Greene et al. 2006; Sellers et al. 2003; Wong et al. 2003) used longitudinal designs to examine the degree to which racial identity buffers racism-related changes in depression. The remainder used cross sectional, correlational designs. In all the studies, participants completed measures of racial identity, perceived racism and a measure of depression or psychological distress. To test the buffering effects of racial identity, all researchers directly examined the statistical interactions of racial identity and racism on measures of distress, with the exception of those who used path analytic models (Sellers et al. 2003).

These studies provide only very limited evidence for the hypothesis that racial or ethnic identity buffers the effects of racism on psychological distress. Of the 12 studies specifically examining effects of racism on distress or depression, only two found evidence of a buffering effect of racial identity on at least one measure of distress (Fischer and Shaw 1999; Mossakowski 2003). One study was a population-based study investigating these issues in Filipino-American adults (Mossakowski 2003). In this study, ethnic identity acted as a buffer only for the predictive effects of a single item measure of discrimination on depressive symptoms. Ethnic identity did not appear to buffer the effects of everyday maltreatment on depressive symptoms. The other study reporting buffering effects on depressive symptoms was a study of African American young adults (Fischer and Shaw 1999). Six studies (Bynum et al. 2007; Fischer and Shaw 1999; Lee 2003, 2005; Sellers et al. 2003; Wong et al. 2003) reported no buffering effects for either distress or depression. Four studies found some evidence that an aspect of ethnic identity (i.e., pride; Lee 2005); public regard (Sellers et al. 2006); commitment/centrality (Noh et al. 1999) or positive attitudes towards other cultures (Banks and Kohn-Wood 2007) may intensify the relationship of racism to distress.1

In contrast, positive main effects of racial identity on distress were obtained in several studies examining dimensions related to ethnic pride or attachment (e.g., positive attachment to one’s ethnic group (i.e., including the MEIM; Phinney 1992), the private regard component of the MIBI or the cultural pride dimension of racial socialization or connection to ethnic group) (Bynum et al. 2007; Lee 2005; Mossakowski 2003; Sellers et al. 2006; Wong et al. 2003). However, some studies obtained null (Fischer and Shaw 1999; Lee 2003; Noh et al. 1999; Wong et al. 2003) or reverse effects (Bynum et al. 2007). The effects for dimensions such as centrality were more mixed, with some studies reporting that greater racial centrality was associated with less negative mood (Sellers et al. 2003), whereas another study failed to find the same connection (Sellers et al. 2006). In one study a measure that more explicitly assess those aspects of identity that address preparedness for discrimination was associated with increased distress (Bynum et al. 2007).

These main effects analyses suggest that the pride and belonging dimensions of racial identity may produce a more general feeling of well-being. Aspects of racial identity may buffer the effects of other stressors common to the research participants that were not assessed in the study. However, the effects of these positive racial identity dimensions were not sufficient to offset the impact of perceived racism, and in particular everyday maltreatment, on distress and depressive symptoms.

Findings from Lee (2005) suggest a complex relationship of centrality and pride to depression. In this study of Asian young adults, there was a significant main effect of Ethnic Identity (EI)-Pride, such that those with relatively high scores on the ethnic pride dimension of the MEIM (derived from a factor analysis conducted in the same sample) had fewer depressive symptoms than those with low scores. However, among those with high EI-Pride scores, the effects of racism on depressive symptoms were stronger than for those who did not feel a great deal of pride in their ethnic group. This suggests that enhancing pride may reduce depression overall, but may be related to greater symptom reports when individuals are exposed to racism. Racial identity as a buffer of cardiovascular reactivity to race-related stress

There are also two studies that examined racial identity as a moderator or buffer of the relationship of race-related stress to an index of cardiovascular response. These measures of cardiovascular reactivity (CVR) appear to be markers for processes involved in the development of hypertension and coronary heart disease. However, it is difficult to evaluate the meaning of reactivity data in some of these studies, since there are some limitations to the presentations of the existing studies. Clark and Gochett (2006) reported finding an inverse relationship between private regard and cardiac output and stroke volume (measures of sympathetic nervous system influences on the heart) before, during, and after racial and non-racial stressors. The authors interpreted the inverse relationship to suggest higher levels of arousal for those high in private regard; however, analyses directly examining the relationship of identity to the change from baseline are not reported. Similarly, Torres and Bowens (2000) reported positive correlations of the Black Racial Identity Attitude Scale (RIAS-B) internalization attitudes (indicating more acceptance of both Black and Caucasian groups) with systolic blood pressure (SBP) reactivity to both race and non-race related stressors. These findings may indicate that individuals with Black oriented identities (i.e., those who are low on internalization) are better prepared to confront episodes of racism as they expect this maltreatment. However, the data are difficult to interpret, as greater increases in SBP may also indicate greater task engagement and no measures were made of level of effort or involvement. Without data on subjective response to the task, it is difficult to interpret these findings.

In contrast, in a study of the main effect of racial identity on both resting and ambulatory blood pressure (BP), Thompson et al. (2002) found that a transitional racial identity, marked by an intense involvement in in-group activities and an “idealization of African American and African American culture and a devaluation of White culture,” was associated with higher levels of resting and ambulatory BP. The authors suggest that a transitional identity may intensify the perception of racial bias and make race-related conflict more salient, increasing the frequency with which individuals experience interpersonal stress. However, no data were available on the race-related social interactions experienced by the participants.

What accounts for the mixed findings on the effects of racial identity?

The effects of racial identity on mental and physical health are complex, and the data do not support a uniformly positive effect of each aspect of racial or ethnic identity on mental health. The bulk of the evidence suggests that ethnic pride may be associated with fewer depressive symptoms overall, but the results indicate that pride and other aspects of ethnic/racial identity are not sufficient to buffer the effects of racism on depressive symptoms for most (but not all) samples. It is important to note that some aspects of racial identity appear to intensify the relationship of racism to depression.

Ethnic pride may not buffer the pain of race-based ostracism, since social rejection is painful, even when other sources of social connection are available (Baumeister et al. 2005; MacDonald and Leary 2005). Further, race-based social rejection or exclusion may heighten the awareness of race-related stereotypes and elicit concerns about stereotype threat. In turn these concerns may evoke feelings of anxiety and shame (Cohen and Garcia 2005; Steele 1997). Messages of cultural pride may not be adequate to counteract the emotional consequences of demeaning treatment.

There is also some evidence that ostracism is associated with a decrease in self-awareness and self-regulation (Baumeister et al. 2005; MacDonald and Leary 2005). This blunting of self-awareness may help the individual block some of the injury to self-esteem associated with social rejection. However, reductions in self-awareness in response to personal threat may also limit the individual’s ability to access self-related schemas (e.g., racial identity or ethnic pride) that might facilitate coping. Laboratory studies are needed to assess the effects of priming racial salience on responses to acute race-related stressors and to evaluate the effects of increasing versus decreasing self-awareness during these manipulations (Baumeister et al. 2005).

The effects of racial centrality appear to be more variable than the effects of racial/ethnic pride and belonging. There may be circumstances in which drawing attention to race and heightening awareness of potential exposure to racism protect individuals from its harmful effects (Fischer and Shaw 1999), but there is also evidence that racial centrality can intensify distress (Sellers et al. 2006). The awareness that one may be targeted for racism may help individuals gather the strength they need to avoid being denied rights or misjudging their own competence, but this awareness can also be exhausting, elicit distress and anger, and erode some relationships. This is consistent with data on the use of avoidance coping in African Americans reported by Thompson Sanders (2006). Further work is needed to identify the types and timing of the complex of racial socialization messages that increase awareness without destroying hope or inflicting a costly emotional burden. The nature of these messages may vary by socioeconomic status and parental involvement, and some personality dimensions (Scott 2003, 2004), and the role of these potential moderators has also not been adequately explored.

There is some evidence that racial identity buffers the effects of racism on self-esteem and some measures of academic performance (e.g., Oyserman et al. 2001; Wong et al. 2003). Failure to find substantial buffering effects for depression and distress may be a function of the need to match the type of coping strategy with the expected outcome. Racial identity is related to self-concept and pride, and as a consequence may have effects primarily on aspects of functioning that are tied to self-concept versus more global affective states.

The data on the effectiveness of racial identity as a buffer of the relationship of racism to BP or BP reactivity is too limited to support firm conclusions. The findings suggest, however, that measures of racial identity may tap psychological dimensions that influence coping with stressors on a day-to-day basis. These schemas may influence the degree to which individuals are able to engage in challenge or feel they must defend themselves from threat. Both engagement and defensiveness influence cardiovascular dynamics. Continued research on the ways in which racial identity affects appraisals of laboratory tasks and everyday events, and in turn influence cardiovascular and neuroendocrine responses, would be very useful.

Social support as a buffer of the effects of racism on mental and physical health

Social support has been defined as the presence or availability of network members who express concern, love, and care for an individual and provide coping assistance (Sarason et al. 1983). Seeking social support involves communication with others (e.g., family, friends, and community members) about events or experiences. Within the Black community, seeking social support has sometimes been more specifically labeled as “leaning on shoulders” (Shorter-Gooden 2004). This term refers to seeking out and talking to others as a means of coping with racial discrimination.

How might social support buffer the effects of racism on distress?

It is widely accepted that social support is beneficial for physical and psychological health (Allgower et al. 2001; Barnett and Gotlib 1988; Symister and Friend 2003). A supportive social network promotes a sense of security and connectedness, helping the individual to understand that discrimination is a shared experience. Group members can serve as models, guiding the individual in effective methods for responding to and coping with discrimination. Placing the event in a collective context can also help the individual to feel more connected to his or her ethnic/racial group and can activate racial identity (Harrell 2000; Mellor 2004). Greater participation in social activities may help to distract individuals and provide them with positive experiences that may buffer the negative impact of a range of stressors including racism (Finch and Vega 2003).

Seeking social support is commonly used as a coping strategy following a racist incident (Krieger 1990; Krieger and Sidney 1996; Lalonde et al. 1995; Mellor 2004; Shorter-Gooden 2004; Swim et al. 2003; Thompson Sanders 2006; Utsey et al. 2000b). In Black college students, Swim et al. (2003) found that 68% of the sample discussed a racist incident with their family, friends, or others. In two separate studies, Krieger found that the vast majority of Black individuals sampled reported “talking to others” in response to racial discrimination (Krieger 1990; Krieger and Sidney 1996). Furthermore, a majority of Black Canadians reported “seeking advice” and “telling others about the discrimination” in response to a hypothetical situation involving housing rejection based on ethnic discrimination (Lalonde et al. 1995). Although social support is hypothesized to serve as an effective strategy for coping with racism, there has been surprisingly limited empirical research testing this hypothesis.

We are aware of only three empirical tests of the hypothesis that social support buffers the effects of racism on distress (Fischer and Shaw 1999; Noh and Kaspar 2003; Thompson Sanders 2006), and four studies examining the hypothesis that social support buffers the effects of racism on physical health-related measures (i.e., self-reported health or cardiovascular reactivity to stress) (Clark 2003; Clark and Gochett 2006; Finch and Vega 2003; McNeilly et al. 1995). Diverse ethnic groups were included in the studies. Some studies assessed the tendency to seek social support or guidance in response to racist events (Noh and Kaspar 2003; Thompson Sanders 2006), whereas others examined the availability of support (i.e., size of network) or quality of general social support (Clark 2003; Finch and Vega 2003; Fischer and Shaw 1999; McNeilly et al. 1995). Further details of the studies are presented in Table 2.

Table II.

Studies of the buffering effects of social support on the relationship of racism to mental or physical health indices

| Authors/Date | Sample | Support | Measures Racism | Outcome | Design | Main effects of social supporta | Buffering effects on healthb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fischer & Shaw (1999) | 119 AA college students | Proportion of casual, friend, and romantic relations with other AA | SRE | MHI | Correlational Cross-sectional, | (YES-POS) Proportion of relationships with AA/MHI | (NO) % AA friends/SRE/MH |

| Noh & Kaspar (2003) | 180 Korean adults from population based sample | Social support seeking when confronting discrimination | Perceived discrimination scale developed for study – series of items ranging from overt (threatened) to covert (ignored) | CES-D-K | Correlational cross sectional | (YES-POS) Social support seeking/CES-D | (NO) Support Seeking/SRE/MH |

| Sanders Thompson (2006) | 156 adults, Black, Asian, European, Hispanic, convenience sample | From the CRI: guidance and support seeking when experiencing specific racism event | Experiences of Discrimination Questionnaire (Thompson Sanders, 1995) | Impact of Events Scale (re-experiencing sx and avoidance sx) (Horowitz, et al., 1979) | Correlational, cross sectional, responses to specific racist event | (NO) Support seeking/Avoidance (NO) Support seeking/Re-experiencing |

(NO) Support seeking/Discrim./Avoidance (NO) Support seeking/Discrim./Re-experiencing |

| Finch & Vega (2003) | 3012 Mexican American adults, population based sample | Emotional Support Instrumental support # of family members in US # of friends/peers in US |

Perceived discrimination measures developed for study – (perception of being disliked, treated unfairly, friend treated unfairly) | Self-reported health (single item) | Correlational, cross sectional | (YES-POS) Emotional support (YES - POS) Instrumental support (YES-POS) Friends in US (YES-POS) Family in US |

(YES – B) Instrumental support/Discrim./Self-reported health |

| Clark (2003) | 64 AA college students, convenience sample | Sarason Social Support Survey (Sarason et al., 1987). SSN – number of supports SSQ – quality of support |

Life Experiences & Stress Scale (Harrell, 1997) | Baseline SBP, DBP Change in SBP, DBP |

Laboratory study, testing correlates of reactivity in response to mental arithmetic task | (YES-NEG) SSQ/Baseline SBP (NO) SSQ/baseline DBP (NO) SSN/baseline SBP (NO) SSN/baseline DBP |

(YES-I and Bc) SSN/perceived racism/SBP reactivity (YES-I and B) SSN/perceived racism/SBP reactivity |

| Clark & Gotchett (2006) | 217 AA youth, convenience sample | Coping responses to racism “talking to someone” | Everyday discrimination scale modified to include the statement “because of your race” | Resting BP | Correlational, cross-sectional | (NO) “Talking to someone” | (NO) “Talking to someone”/perceived racism/SBP and DBP level (YES-B) Low “Talking to someone”/high perceived racism/Elevated BP status |

| McNeilly et al (1995) | 30 AA adults, convenience sample | Presence or absence of supportive confederate | Racist provocation (i.e., debate with White confederate about racially noxious topics) vs. non-race-related topics | Baseline SBP, DBP Change in SBP, DBP in response to race-related and non-race-related stressors |

Laboratory study, manipulate the presence of absence of supportive confederate during two debates (race & non-race related) | N/A | (NO) Presence of support/racist provocation/BP |

Note. sx = symptoms; discrim. = discrimination. SBP = systolic blood pressure; DBP = diastolic blood pressure. BP = blood pressure. SRE = Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996). MHI = Mental Health Inventory (Veit & Ware, 1983). CES-D-K = Korean version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Noh et al., 1998; Radloff, 1977). CRI = Coping Responses Inventory–Adult Form (Moos, 1993).

For main effects analysis, the type of support and specific outcome measure are listed as follows: type of support/outcome. The results are categorized as follows: (NO) = No main effect; (YES-POS) = Significant main effects such that increasing scores on listed dimensions of social support are associated with lower symptom reports; (YES-NEG) = Significant main effects such that increasing scores on listed dimensions of social support are associated with greater symptom reports.

(NO) = No buffering effect; (YES-I) = Significant interaction effect, such that the relationship of racism to symptoms is stronger for those with high scores on listed dimensions of social support. (YES-B) = Significant interaction effect, such that the relationship of racism to symptoms is weaker for those with high scores on listed dimensions of social support.

. For both SBP and DBP, the SSN is negatively related to BP reactivity for those reporting low levels of racism and positively related for those reporting high levels of racism.

The three studies examining the buffering effects of seeking social support on the relationship of racism to distress failed to find positive effects (Fischer and Shaw 1999; Noh and Kaspar 2003; Thompson Sanders 2006). However, two of these three studies found main effects of social support on depressive symptoms.

The effects are more mixed among the four studies examining the buffering effects of support on a health-related outcome. Finch and Vega (2003) found robust effects of instrumental support on perceived health in a population-based sample of Mexican Americans. Discrimination was not related to health among those with high levels of support, but was associated with poorer health for those with low levels of support. Two studies found buffering effects of support seeking, but only for those who were exposed to low levels of racism (Clark 2003; Clark and Gochett 2006). Specifically, Clark (2003) reported that self-reported quantity and quality of social support were associated with reduced DBP reactivity to a non-racial stressor (i.e., mental arithmetic), but only for those who had experienced relatively low levels of racism over the course of their lives. Similarly, in a school-based study, Clark and Gochett (2006) found that youth who indicated that they would “talk to others” had a lower incidence of elevated BP (above 90th percentile) than those who did not endorse this item, but these effects were seen only among those who experienced low levels of racism. In contrast, among those exposed to high levels of racism, “talking to others” was associated with a higher prevalence of elevated BP. Finally, in a laboratory study, McNeilly et al. (1995) reported that providing support (in the form of a supportive confederate) did not reduce cardiovascular reactivity in response to racist provocation (i.e., debating about race-related topics), but did reduce self-reported anger. There are two additional studies that examined the relationship of support to race-related stress in African Americans, but they did not directly test the hypothesis that social support buffers the effects of racism on psychological distress (Scott and House 2005; Utsey et al. 2000a, b).

Despite the generally null findings of the quantitative studies, two qualitative reports about seeking social support in response to ethnic or racial discrimination suggest beneficial effects. In a diary study of perceived discrimination, participants reported that it was helpful to discuss racist incidents with another person (Swim et al. 2003). Similarly, African American men participating in an African-centered support group for confronting racism reported decreases in levels of anger and frustration. They also reported engaging in fewer interpersonal conflicts with significant others after attending the support group (Elligan and Utsey 1999).

What accounts for the mixed findings on social support?

Overall, the quantitative literature provides minimal support for the hypothesis that social support (either seeking social support or having a supportive network) buffers the impact of racism on psychological health. It also provides very mixed support for the notion that social support buffers racism effects on indices of physical health. There is some suggestion that social support may be helpful at low levels of stress exposure, but exacerbates difficulties at high levels of exposure. Yet, these results are contrary to anecdotal reports or findings from qualitative studies, and largely contrast with the findings from other literatures on the buffering effects of support in the face of other stressors (mostly medical illnesses). What accounts for these variations?

Measures and research design

General difficulties with the social support research have been outlined by Uchino (2006). Variations in the conceptualization and measurement of social support make the results of studies examining the effects of support as a buffer of the effects of racism on distress or health difficult to interpret. In the studies reviewed, four separate support-related constructs have been studied: seeking support to obtain guidance for ways to manage racism; general support network size, general support network quality, and the proportion of relationships with people of the same ethnicity. The quality of the measurement instruments also varies, with some studies assessing social support seeking using two questions in a self-report survey or diary (Noh and Kaspar 2003; Swim et al. 2003).

The research designs of some studies also have some limitations, as cross sectional correlational designs fail to reveal the direction of the effects. In the Clark and Gochett (2006) study, there are some correlations between exposure to higher levels of racism and seeking support, suggesting that the level of support seeking is in fact a function of the degree of stress exposure. Prospective cohort and laboratory studies may be necessary to more clearly distinguish the direction of the relationship between support and distress. Different types of support may be necessary at different points in time, and no studies have examined perceived needs for support at different stages in the experience of ethnicity-related maltreatment. For example, concrete advice and emotional support may be needed at the time of the incident, whereas support focused on meaning and hope may be needed as individuals confront the possibility of more sustained exposure.

Social constraint and facilitation

Some of the failure to find positive effects associated with social support may be a function of issues related to both social constraint and social facilitation. Lepore and Revenson (2007) propose that social constraints limit the effectiveness of certain social support interventions. Seeking support for race-related maltreatment may entail discussions that are anxiety provoking for both the seekers and givers of support. For members of stigmatized groups, discussions of racism may evoke recollections that feel uncontrollable and are stressful. For members of a majority out-group, stereotype threat may be evoked if individuals become concerned about appearing cruel, uncaring, or insensitive when discussing race-related conflict (Richeson and Shelton 2007). Anxiety on the part of both the in-group and out-group members may inhibit effective communication about race-related incidents. When individuals receive messages that tend to minimize or deny aspects of their experience, support seeking may be ineffective and associated with increased versus decreased distress (Badr and Taylor 2006). Research on the dynamics of interracial communication may provide guidance for further research on the types of communication that can minimize social constraints and facilitate inter-racial communication (Czopp et al. 2006; Richeson and Shelton 2005).

As Utsey et al. (2002) points out, social facilitation may increase distress when individuals discuss discrimination with other members of their group. The experience of sharing episodes of ethnicity-related maltreatment may arouse greater anger as individuals exchange accounts of their experiences. If the situations appear hopeless or if individuals in the discussion have had negative experiences managing race-related interactions themselves, other negative emotions, including fear, frustration, grief, shame and loss, may also be evoked. Further research is needed to determine how variations in the circumstances in which support is sought and in the content of support message confer different costs and benefits to the target of discrimination. It will be important to understand how best to acknowledge the difficulties and pain associated with exposure to discrimination without eliminating hope or generating additional stress.

Confrontation and anger expression

Race-related maltreatment evokes anger (Brondolo et al. 2008; Broudy et al. 2007; Landrine and Klonoff 1996). Consequently, many models of coping with racism recognize the need to address the anger evoked by ethnicity-related maltreatment (Mellor 2004), and some of the seminal studies of the effects of racial stress examined anger coping (Harburg et al. 1979, 1991). Anger coping strategies used in response to ethnicity-related maltreatment may address two goals. The first involves using anger coping strategies, including confrontation, to influence the outcome of the race-related conflict. For example, the expression of anger can be used to motivate the perpetrator to change his or her behavior or to motivate others to take action (Swim et al. 2003). The second goal of anger coping strategies is to manage the emotional burden created by the anger.

Researchers have used several different approaches to assess constructs related to anger expression and confrontation. In some cases, anger coping that involves directly protesting maltreatment has been subsumed under the term confrontation coping (Noh et al. 1999). In other cases, researchers have directly examined the effects of different strategies for anger expression, including outward anger expression (Anger-Out) or anger suppression (Anger-In) (e.g., Dorr et al. 2007).

Despite the obvious importance of studying the effects of anger coping, there have been relatively few studies directly addressing these issues. Specifically, there have been two survey studies that examine the effects of confrontation coping as a buffer of the relationship of racism to distress (Noh et al. 1999; Noh and Kaspar 2003). There have been five studies examining the effects of anger coping or confrontation as a means of managing racist interactions on BP (Armstead and Clark 2002; Dorr et al. 2007; Krieger 1990; Krieger and Sidney 1996; Steffen et al. 2003). Details of these studies are presented in Table 3.

Table III.

Studies of the buffering effects of anger expression on the relationship of racism to mental and physical health indices

| Authors/Date | Sample | Anger Expression | Measure Racism | Outcome | Design | Main effects of anger suppressiona | Buffering effectsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armstead et al (1989) | 68 Black and White women | Framingham Anger Discuss & Anger Suppression | Racist provocation through film vs. Anger provocation through film clip | Baseline SBP and DBP, BP reactivity to the tasks | Laboratory stressor, two tasks, measurement of baseline and changes in BP. | (YES-POS) Anger Suppression/SBP (YES-POS) Anger Suppression/DBP |

(YES-B) Anger-discuss/racist provocation scene/BP reactivity |

| Krieger (1990) | 51 Black and 50 White women, population -based sample | “kept quiet” versus “talked to others” | Study-specific survey asking about experiences of discrim. in different contexts | Self reported HTN diagnosis | Cross sectional correlational, no formal test of moderation | NA | (YES-I) “Keeping quiet and accepting it”/Discrim./HTN diagnosis |

| Krieger & Sidney 1996 | 4086 Black and White men and women, population -based sample | “Do something” versus “Accept as fact of life” “Keep it to self” vs. “talk to others” |

Study specific survey asking about experiences of discrim. in different contexts | BP levels | Correlational, cross sectional, no explicit test of moderation | NA | (YES-I) “Accepted it and kept it to themselves”/discrim./BP |

| Steffen et al. (2003) | 69 AA | MAS | PRS | ABP day and night | Correlational, cross sectional | (YES-POS) Anger-In/Night-time ABP | (NO) Anger-In |

| Dorr et al 2007 | 24 Black and 26 White Men | Manipulation in which ability to express anger toward confederate in study versus distraction and inhibition of anger | Two debates one with racist theme, one without | Autonomic and cardiovascular reactivity, including BP reactivity | Experimental study, laboratory protocol, anger inhibition versus expression is experimentally manipulated | N/A | (YES I) Inhibition/racist debates/slower BP reactivity/Whites and Blacks (YES-I) Anger Expression/racist debates/slower BP recovery/Blacks only |

Note. HTN = Hypertension. ABP = ambulatory blood pressure. BP = blood pressure. SBP = systolic blood pressure. DBP = diastolic blood pressure. MAS = Multidimensional Anger Scale (Siegel, 1986). PRS = Perceived Racism Scale (McNeilly et al., 1996).

For the main effects analyses the results are listed as follows: type of anger expression/outcome. The results are categorized as follows: NA = not applicable, with no main effect tested. (YES-POS) = Significant main effects such that increasing scores on listed dimensions of anger expression are associated with higher levels of ABP.

For the interaction effects, the results are listed as follows: type of anger expression/type of discrimination/outcome. The results are categorized as follows: (NO) = No buffering effect; (YES-I) = Significant interaction effect, such that the relationship of racism to symptoms is stronger for those with high scores on listed dimension of anger expression. (YES-B) = Significant interaction effect, such that the relationship of racism to BP is weaker for those with high scores on listed dimensions of anger expression.

In two population-based samples of Asian immigrants, Noh and colleagues examined confrontation coping using measures which include an item assessing direct protests to the perpetrator. In the South Asian sample (i.e., composed largely of Chinese and Vietnamese), Noh and Kaspar (2003) reported no effects of confrontation on the relationship of perceived discrimination to depression. In contrast, in a study of Korean immigrants, the authors reported that personal confrontation coping (i.e., directly protesting or talking to the perpetrator) moderated the effects of discrimination on depression, such that those who were more likely to confront reported less depression in the face of discrimination than those who indicate they are less likely to confront (Noh et al. 1999).

A recent diary study by Hyers (2007) examined costs and benefits associated with confrontation coping, although no measure was made of depression or health. She considered outcomes including rumination-related behaviors (i.e., feelings of emotional upset, regret, wishing to respond differently in the future) and experiences of self-efficacy (i.e., “the perpetrator was educated”) as well as interpersonal conflict. These intermediate outcomes may be predictors of depression over the long run, and potentially serve to maintain the stress associated with the episodes of racism. Hyers reported that when women responded to incidents of racism or sexism with confrontation coping, they were less likely to ruminate and more likely to feel they had been efficacious. Those who did not confront were more likely to report a benefit of avoiding interpersonal conflict; however, it is not clear if the women who did confront actually experienced more conflict.

In five studies using different methodologies, the effects of anger coping on BP levels or reactivity and recovery were examined (Armstead et al. 1989; Dorr et al. 2007; Krieger 1990; Krieger and Sidney 1996; Steffen et al. 2003). The results were fairly consistent and are detailed in Table 3. The main effects analyses indicate that suppressing anger in the face of discrimination is associated with higher levels of BP or poorer cardiovascular recovery from race-related stress exposure. However, there is also some evidence that, for African Americans, expressing anger may be associated with poorer cardiovascular recovery as well.

In two population-based samples, Krieger and colleagues examined the effects of exposure to discrimination and responses to discrimination, contrasting the effects of “doing something about it” with “accepting it as a fact of life”. Among a small sample of Black women, those who reported “doing something about it (discrimination)” were less likely to have a hypertension diagnosis than those who “accepted and kept quiet about it” (Krieger 1990). In Krieger and Sidney (1996), a large scale population-based study of Black and White individuals, the blood pressure levels of those who reported “doing something about it” were lower than those of individuals who reported “accepting it.” Statistical tests of moderation were not performed, making it difficult to determine if buffering effects were present.

Steffen et al. (2003) reported that trait anger suppression was independently associated with ambulatory DBP in a convenience sample of African Americans. However, neither anger suppression nor expression moderated the effects of racism on ambulatory BP. Armstead et al. (1989) and Dorr et al. (2007) conducted laboratory studies examining the relationship of anger coping to BP response to a racist stressor. Armstead et al. (1989) reported that for Blacks anger suppression was marginally associated with greater SBP at baseline. A style of anger coping in which anger is outwardly expressed was marginally associated with baseline levels of mean arterial pressure and reduced SBP and DBP reactivity to the racist stressor.

In the Dorr et al. study (2007), African American and European American participants engaged in race and nonrace-related debates facing a European American confederate. Following the tasks participants were given opportunities to express versus inhibit anger. The authors reported that for both African Americans and European Americans, anger inhibition was associated with slower recovery of indices of total peripheral resistance, a measure of vascular response. For African Americans, BP and HR recovery was slower when they were allowed to express their anger than when they were asked to inhibit it, and recovery was also slower than the recovery of EA who were able to express their anger. These effects suggest that anger suppression exacerbates vascular recovery to stress for both groups; whereas outward anger expression exacerbates cardiac and other CV indices of recovery to stress for Blacks.

The authors suggest that one possible explanation for these findings is that anger suppression can lead to rumination if issues are not resolved satisfactorily. However, anger expression may lead to anxiety about retaliation or abandonment if social relations are threatened by direct expression of anger. Both rumination and persistent anxiety may be associated with sustained physiological activation following stress exposure (Brosschot et al. 2006).

What accounts for the variations in the effects of confrontation as a buffer of the effects of racism on depression?

The specific effects of confrontation coping are difficult to interpret, since confrontation coping is subsumed under the general heading of approach coping or problem solving coping and includes items measuring social support seeking as well as “going to the authorities”. Second, the type of confrontation (i.e., hot and angry versus cold and unemotional) is generally not specifically examined, yet laboratory research suggests that the effects of the confrontation depend in part on the emotional quality of the confrontation (Czopp et al. 2006).

Although the limited literature suggests that most Black and White individuals report trying to “do something” about racism (Krieger and Sidney 1996; Plummer and Slane 1996; Thompson Sanders 2006), diary studies suggest that individuals report thinking about confrontation or indirectly or non-verbally expressing their anger more often than they actually engage in direct anger expression (Hyers 2007). Measures are needed that separate intent from action or more explicitly identify the specific actions taken.

It is also necessary to consider the context in which the conflict occurs when evaluating the effects of anger coping or confrontation. Individuals will hesitate to express anger directly if they believe there will be retaliatory consequences for this anger expression. In any given interaction, individuals with relatively lower levels of power or status are more likely to suppress anger than high power individuals (Gentry et al. 1973). The location of the conflict (i.e., work or social arena) may also influence the choice of coping strategies (Brondolo et al. 2005b). Cultural variations in the importance of maintaining relationships may also affect the outcomes associated with confrontation (Noh et al. 1999; Suchday and Larkin 2004). Research is needed to clearly differentiate among different types of confrontation strategies and to identify situational and cultural variations in the types of strategies used and their effectiveness.

Some of the health effects of different individual-level coping strategies are likely to be a function of the efficacy of the coping strategies themselves. If the strategies for confrontation and anger coping are effective on some dimensions (e.g., reducing overt expressions of prejudice), but costly on others (e.g., social relations), individuals may not perceive themselves as having appropriate coping resources, making it more likely that they will perceive interracial or race-based maltreatment as stressful. Evaluating a broad range of outcome measures from the target’s perspective (e.g., mental and physical health, rumination, satisfaction with outcome, perceived benefits) is critical. Investigating the perceptions of these different coping strategies from the perspective of others is also important. The growing literature on other’s perceptions of confrontation and other coping strategies (Czopp et al. 2006; Kawakami et al. 2007) can provide guidance for future studies on anger coping. More knowledge regarding the perceptions of different coping strategies by individuals of other ethnicities/races can help guide individuals as they weigh the costs and benefits of various responses.

Summary and future directions

The strongest and clearest conclusion that can be drawn from this review is that there is a significant need for further research on strategies for coping with racism. No coping strategy has emerged as a clearly successful strategy for offsetting the mental or physical health impacts of racism. Instead, each approach has some demonstrated strengths, but also considerable side effects or limitations.

Ethnic and racial identity develop to meet multiple needs, including enhancing one’s pride and commitment to one’s cultural group as well as helping individuals develop meaningful strategies for managing discrimination based on racial or ethnic bias. Studies suggest that racial identity, particularly racial or ethnic pride and belonging may have beneficial effects in some circumstances. But these components of identity are not sufficient to ameliorate the effects of racism on the development of depressive symptoms and may increase the detection of threat and the perception of harm.

Involvement with only one type of identity may restrict the individuals’ ability to consider multiple perspectives and learn a range of coping options. Instead, in an increasingly multicultural society, it will be important to understand the best ways to help individuals master the complex psychological tasks involved in maintaining individual, group and national identities, particularly when the values at one level contrast with the values at another. Oyserman has specifically suggested that a “possible selves” approach, encouraging individuals to incorporate aspects of different types of group identities, may be of benefit (Oyserman et al. 2007).