Abstract

Background

Tobacco addiction is a relapsing disorder that constitutes a substantial worldwide health problem, with evidence suggesting that nicotine and nicotine-associated stimuli play divergent roles in maintaining smoking behavior in men and women. While animal models of tobacco addiction that utilize nicotine self-administration have become more widely established, systematic examination of the multiple factors that instigate relapse to nicotine-seeking have been limited. Here, we examined nicotine self-administration and subsequent nicotine-seeking in male and female Sprague-Dawley rats using an animal model of self-administration and relapse.

Methods

Rats lever pressed for nicotine (0.03 and 0.05 mg/kg/infusion, IV) during 15 daily 2-h sessions, followed by extinction of lever responding. Once responding was extinguished, we examined the ability of previously nicotine-paired cues (tone+light), the anxiogenic drug yohimbine (2.5 mg/kg, IP), a priming injection of nicotine (0.3 mg/kg, SC), or combinations of drug+cues to reinstate nicotine-seeking.

Results

Both males and females readily acquired nicotine self-administration and displayed comparable levels of responding and intake at both nicotine doses. Following extinction, exposure to the previously nicotine-paired cues or yohimbine, but not the nicotine-prime alone, reinstated nicotine-seeking in males and females. Moreover, when combined with nicotine-paired cues, both yohimbine and nicotine enhanced reinstatement. No significant sex differences or estrous cycle dependent changes were noted across reinstatement tests.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate the ability to reinstate nicotine-seeking with multiple modalities and that exposure to nicotine-associated cues during periods of a stressful state or nicotine can increase nicotine-seeking.

Keywords: female, nicotine, self-administration, reinstatement, relapse, yohimbine

1. Introduction

Tobacco addiction constitutes a critical health issue, with an estimated 1.3 billion daily tobacco smokers worldwide (Guindon and Boisclair, 2003; Thun and da Costa e Silva, 2003). Despite a substantial decrease in the percentage of the population using tobacco over the last four decades, tobacco use remains the leading, preventable cause of premature death and disease in the United States, responsible for 440,000 deaths each year (Fellows et al., 2002). Similar to other drugs of abuse, one of the most significant problems for long-term treatment of nicotine dependence is the high incidence of relapse to drug-seeking and drug-taking following prolonged periods of abstinence. In fact, the majority of smokers who quit will relapse (Fiore, 2000; Shiffman et al., 1998), and nearly all smokers who relapse after an initial quit attempt will return to regular smoking (Brandon et al., 1990; Chornock et al., 1992; Kenford et al., 1994).

Three primary factors have been found to contribute to nicotine relapse in humans: nicotine-associated cues (Perkins et al., 1999; Perkins et al., 1994), stress (Brandon et al., 1990; Patton et al., 1997), and exposure to the drug itself (Chornock et al., 1992; Sofuoglu et al., 2005). Similarly, these trigger factors have been used in animal models of relapse to drug-seeking behavior, particularly in the extinction/reinstatement model following withdrawal from chronic nicotine self-administration, whereby exposure to nicotine-paired stimuli (LeSage et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2006), footshock stress (Buczek et al., 1999; Martin-Garcia et al., 2009; Yamada and Bruijnzeel, 2011; Zislis et al., 2007), or noncontingent nicotine administration (Le et al., 2006; Martin-Garcia et al., 2009; Shaham et al., 1997; Shram et al., 2008) will reinstate nicotine-seeking as measured by responding on a previously nicotine-paired lever.

While animal models of nicotine addiction have increasingly been utilized, a number of unanswered questions remain, including the issue of sex differences in nicotine-taking and -seeking. This constitutes an important clinical issue, as it has been demonstrated that female smokers progress more rapidly from casual use to dependence, have fewer and shorter abstinence periods, and have a more difficult time remaining abstinent (see Perkins, 2001 for review). Similarly, preclinical evidence suggests some degree of enhanced motivation for nicotine/nicotine-associated cues in female rats. In one study, females exhibited greater responding for low doses of nicotine (i.e., 0.02 mg/kg) under a fixed ratio 5 (FR5) and progressive ratio (PR) schedules of reinforcement (Donny et al., 2000). Similar enhancements in FR acquisition and PR responding for low doses of nicotine (0.005 mg/kg) have also been noted for female adolescent rats (Lynch, 2009), and enhanced oral nicotine self-administration has been reported for adolescent female mice (Klein et al., 2004). In another study, Chaudhri et al. (2005) noted enhanced FR5 responding in female rats that self-administered higher doses of nicotine (i.e., ≥ 0.06 mg/kg) alone. When nicotine infusions were paired with a conditioned stimulus (i.e., 1 s presentation of a cue light, followed by 60 s offset of the houselight), significant increases in responding were noted for lower doses of nicotine (i.e., ≤ 0.06 mg/kg) in both sexes, an effect that was greater in females. In addition to highlighting the prominent contribution of nicotine-paired stimuli to enhance nicotine reinforcement, these results collectively suggest that females may be more motivated to obtain nicotine and may be more sensitive to the effects of nicotine-paired stimuli.

Despite the initial research examining sex differences in nicotine self-administration, no studies to date have examined reinstatement of nicotine-seeking in females, nor examined sex differences in reinstatement. Moreover, although clinical research suggests that the menstrual cycle in women can affect craving and propensity to relapse following abstinence (Allen et al., 2008; Carpenter et al., 2006; Franklin et al., 2004), it has not been determined whether nicotine-seeking in rats may vary as a function of the estrous cycle. Here, we investigated the role of sex and estrous cycle in mediating nicotine-taking and nicotine-seeking using a model of nicotine self-administration and relapse in male and freely cycling female rats. Moreover, we examined the separate, as well as interactive, effects of nicotine-paired cues, a pharmacological stressor (yohimbine), and noncontingent nicotine administration on reinstatement of nicotine-seeking in male and female rats. Yohimbine is a norepinephrine (NE) α2 receptor antagonist that increases NE release in several neural structures implicated in stress, including the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Forray et al., 1997) and the amygdala (Khoshbouei et al., 2002), and has been shown to produce stress-like responses (e.g., increases in subjective anxiety, blood pressure, and sympathetic symptoms) in humans (Charney et al., 1983; Holmberg and Gershon, 1961) and to induce craving in abstinent drug-dependent subjects (Stine et al., 2002). Similarly, yohimbine produces stress activation (e.g., increases in plasma corticosterone, arterial blood pressure, heart rate, and potentiated startle response) in animals (Davis et al., 1979; Lang and Gershon, 1963; Suemaru et al., 1989) and reinstates drug-seeking for heroin (Banna et al., 2010), alcohol (Gass and Olive, 2007; Le et al., 2005), methamphetamine (Shepard et al., 2004), and cocaine (Anker and Carroll, 2010; Bongiovanni and See, 2008; Feltenstein et al., 2011; Feltenstein and See, 2006). Moreover, yohimbine has been shown to enhance cue-induced reinstatement of heroin-(Banna et al., 2010) and cocaine-seeking (Buffalari and See, 2011; Feltenstein et al., 2011; Feltenstein and See, 2006).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Aged-matched male (initial weight 250–300 g, P59–67) and female (initial weight 175–225 g, P57–74) Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) were individually housed in separate temperature- and humidity-controlled vivariums on a 12 h light-dark cycle (lights on at 06:00). All experimental procedures occurred between 07:00 and 16:00. In the home cage, animals had access to water ad libitum and were maintained on a controlled diet (20–25 g/day) of standard rat chow (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) for the duration of each experiment. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical University of South Carolina and conformed to federal guidelines as described in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Rats” of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources on Life Sciences, National Research Council.

2.2. Surgery

Rats were anesthetized using a mixture of ketamine hydrochloride and xylazine (66 and 1.33 mg/kg, respectively, IP) and equithesin (sodium pentobarbital 4 mg/kg, chloral hydrate 17 mg/kg, and 21.3 mg/kg magnesium sulfate heptahydrate dissolved in 44% propylene glycol, 10% ethanol solution, IP), and jugular catheters were inserted and maintained using previously described methods (Reichel et al., 2011). For assessment of catheter patency, rats occasionally received a 0.1 ml IV infusion of methohexital sodium (Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, USA; 10 mg/ml dissolved in 0.9% physiological saline), a short-acting barbiturate that produces a rapid loss of muscle tone when administered intravenously.

2.3. Nicotine self-administration and extinction

Rats lever pressed for nicotine in standard self-administration chambers linked to a computerized data collection program (MED-PC, Med Associates Inc., St. Albans, VT, USA). The chambers were equipped with two levers, a white stimulus light above the nicotine-paired (i.e., active) lever, a tone generator, and a white house light. Each chamber was contained within a sound-attenuating cubicle equipped with a ventilation fan.

Rats self-administered nicotine (nicotine bitartrate dissolved in 0.9% physiological saline; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO, USA) during daily 2-h sessions according to an FR1 schedule of reinforcement. All nicotine doses are reported as the free base and the pH of all solutions was adjusted to 7.4 using dilute NaOH. At the start of each session, the catheter was connected to a liquid swivel (Instech, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA) via polyethylene 50 tubing (0.023” ID × 0.05” OD) that was encased in steel spring leashes (Plastics One Inc., Roanoke, VA, USA). The house light signaled the initiation of the session and remained illuminated throughout the entire session. Lever presses on the active lever resulted in a 2-s activation of the infusion pump (50 µl bolus) and a 5-s presentation of a stimulus complex (white stimulus light above the active lever and activation of the tone generator; 4.5 kHz, 78 dB). For animals in the 0.03 mg/kg nicotine group, each infusion consisted of 0.01 mg (males; n=33) or 0.0085 mg (females; n=31). For animals in the 0.05 mg/kg nicotine group, each infusion consisted of 0.016 mg (males; n=27) or 0.014 mg (females; n = 29). Bolus amounts of nicotine were based on a group average body weight of 325 g (males) and 275 g (females) at the time of self-administration; however, daily nicotine intake was calculated individually for each animal based on actual body weight. After each infusion, responses on the active lever were recorded, but resulted in no consequences during a 20-s time-out period. Inactive lever responses were also recorded, but had no programmed consequences. All self-administration sessions were conducted 6 days per week to criteria (15 sessions ≥ 10 infusions per session) for a total period of 15–21 days. Following chronic self-administration and before the first reinstatement test, animals underwent daily 2-h extinction sessions. During each session, responses on both levers were recorded, but had no consequences.

2.4. Reinstatement of nicotine-seeking

Once active lever responding extinguished to criteria (minimum of fourteen extinction sessions with ≤ 15 active lever responses for two consecutive days), all animals underwent five 2-h reinstatement tests. Prior to each reinstatement test, each rat received either an injection of yohimbine hydrochloride (2.5 mg/kg dissolved in double distilled water, IP; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO, USA, 30 min prior to testing), nicotine bitartrate (0.3 mg/kg dissolved in 0.9% physiological saline, SC, immediately prior to testing), or vehicle (0.9% physiological saline, IP, immediately prior to testing). The treatment parameters for yohimbine (Feltenstein et al., 2011; Le et al., 2005; Shepard et al., 2004) and nicotine (Clemens et al., 2010; Dravolina et al., 2007; Le et al., 2003) were selected based on previous studies in rats. During reinstatement testing, responses on the active lever either resulted in a 5 s presentation of the previously nicotine-paired light+tone cues in the absence of nicotine reinforcement (i.e., “cue”, “yohimbine + cue”, and “nicotine-prime + cue” reinstatement tests) or no programmed consequences (i.e., “yohimbine” and “nicotine-prime” reinstatement tests). Reinstatement tests were counterbalanced based on active lever responding during the last three days of nicotine self-administration, and animals underwent extinction sessions between reinstatement tests until they reached criteria (≤ 15 active lever responses per session for two consecutive days).

2.5. Estrous cycle monitoring

In order to ascertain estrous cycle stages, vaginal lumen samples were collected immediately prior to and following each of the five reinstatement tests. However, in order to habituate females to the vaginal cytology procedure, samples were taken daily across the entire experiment. Vaginal lumen samples were collected by gently flushing 30 µl of double distilled water and extracting the sample using a micropipette and 100 µl pipette tips. Samples were placed on glass slides, stained using Quick-Dip Hematology Stain (Mercedes Medical, FL, USA), examined using a light microscope (10× magnification), and the estrous cycle phases then classified according to previously published criteria (Marcondes et al., 2002).

2.6. Data analysis

Mixed factors repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to analyze lever responses and nicotine intake (mg/kg) during nicotine self-administration (last seven days) and extinction (first seven days), with sex and session as the between-and within-subjects factors, respectively. For reinstatement testing, three-way ANOVAs were used to analyze lever responses with sex (male, female), cue (no cue, cue), drug (vehicle, yohimbine, nicotine-prime), and estrous phase (proestrus, estrus, diestrus I/II) as factors, where appropriate. Significant interactions were further investigated using ANOVAs or independent t tests, where appropriate. Data points were eliminated if they were 2.5 standard deviations beyond the group mean. All post hoc analyses were conducted using Student-Newman-Keuls with the alpha set at 0.05, and only significant F or t values are presented.

3. Results

3.1. Nicotine self-administration and extinction

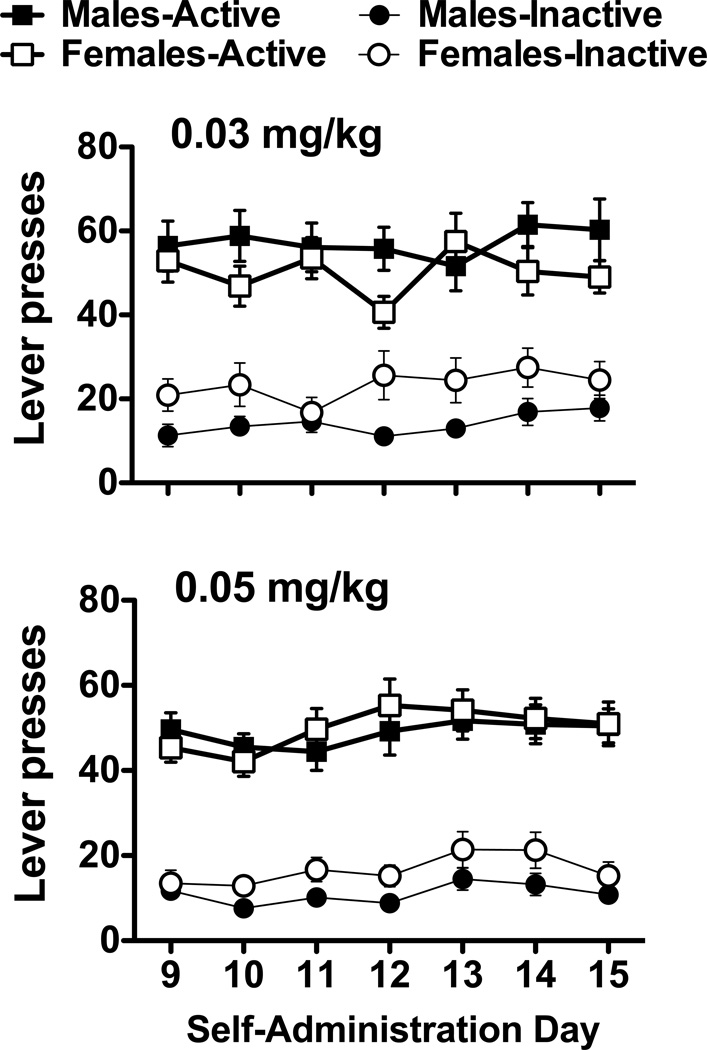

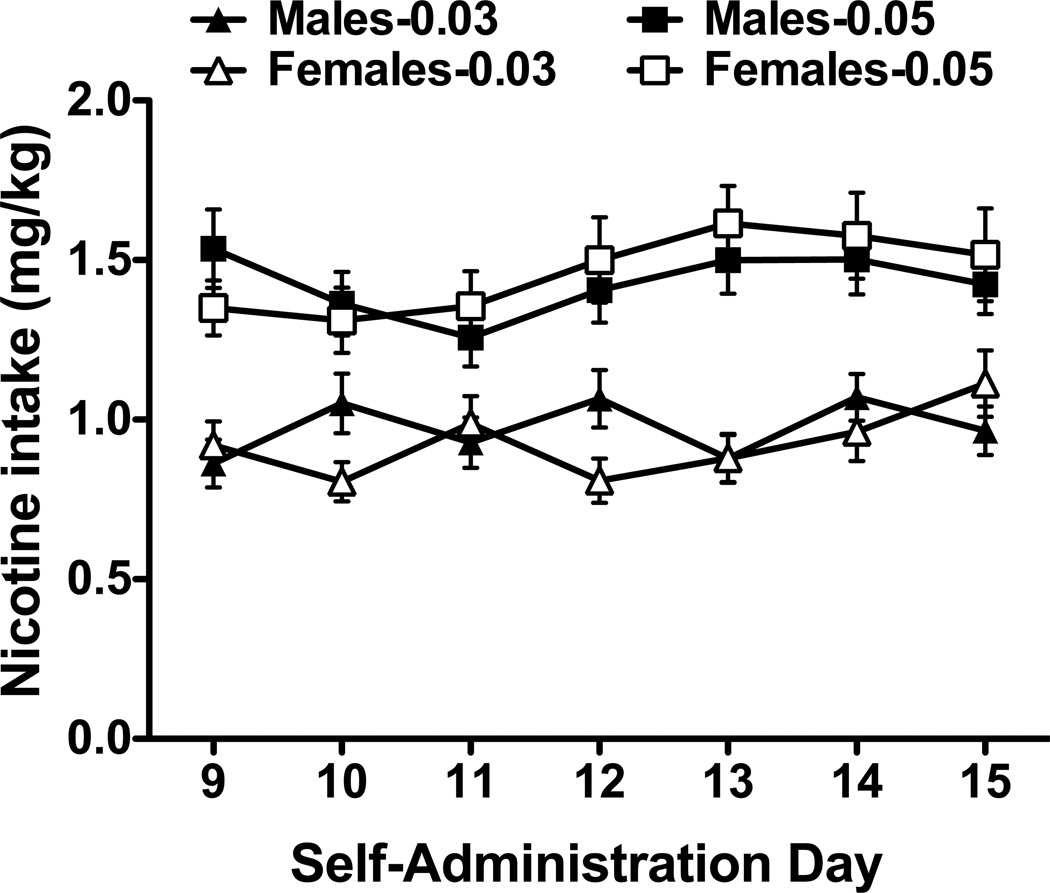

Rats readily acquired nicotine self-administration, responded preferentially on the nicotine-paired lever and displayed stable lever responding (Fig. 1). For both doses of nicotine, active lever responding was significantly greater than inactive lever responding (Fs1,108–124 = 112.00–116.43, ps < 0.001), but no significant differences in active lever presses were noted for the sex or day main effects, or for the sex by day interactions. Inactive lever responding was uniformly low in both males and females across all phases of the study. Thus, while inactive lever responding is shown in the figures for comparison purposes, none of the statistical analyses were significant. Animals also displayed stable nicotine intake (mg/kg; Fig. 2). Interestingly, analyses revealed a significant sex by day interaction for the 0.03 mg/kg group (F6,372 = 2.94, p < 0.01) and a significant day main effect for the 0.05 mg/kg group (F6,324 = 2.45, p < 0.05). However, none of the posthocs were significant.

Fig. 1.

Nicotine self-administration for male and female rats. Average active and inactive lever responses (mean ± SEM) are shown for the last week of nicotine self-administration for animals in the 0.03 and 0.05 mg/kg groups.

Fig. 2.

Nicotine intake (mg/kg) for male and female rats. Average intake (mean ± SEM) is shown for the last week of nicotine self-administration for animals in the 0.03 and 0.05 mg/kg groups.

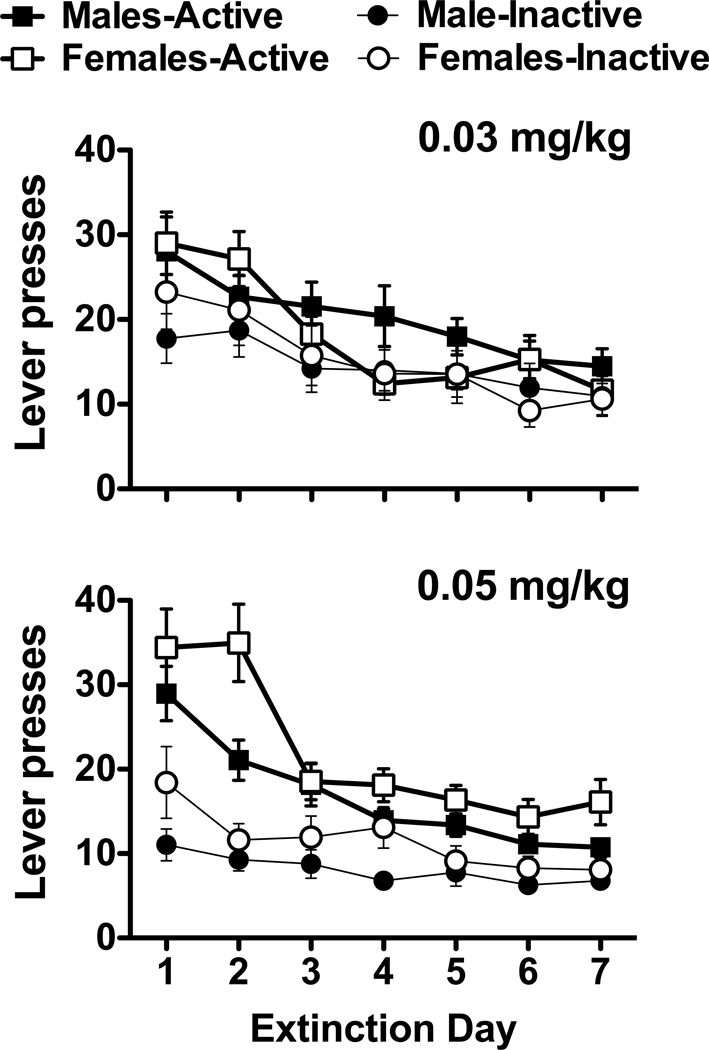

Following the removal of nicotine reinforcement, lever responding in males and females in both nicotine groups decreased steadily over the course of daily extinction sessions (Fig. 3). A 2 × 7 ANOVA of active lever responding for animals in the 0.03 mg/kg dose only revealed a significant main effect for session (F6,348 = 11.62, p < 0.001), with post hoc analyses revealing significantly greater responding during the first two days of extinction (ps < 0.05). Notably, female rats in the 0.05 mg/kg dose group exhibited higher levels of responding than males during extinction, an effect comparable to previous studies for cocaine (Feltenstein et al., 2011; Fuchs et al., 2005; Kippin et al., 2005) and supports evidence suggesting the enhanced role of nicotine-associated environmental stimuli in females (see Perkins, 2009 for review). Similar analyses revealed significant main effects for sex (F1,54 = 4.76, p < 0.05) and session (F6,324 = 23.27, p < 0.001), with post hoc analyses revealing significantly greater responding during the first two days of extinction (ps < 0.05). However, the sex by session interaction was not significant.

Fig. 3.

Extinction of nicotine-seeking for male and female rats. Average active and inactive lever responses (mean ± SEM) are shown for the first week of extinction sessions for animals in the 0.03 and 0.05 mg/kg groups.

3.2. Reinstatement of nicotine-seeking

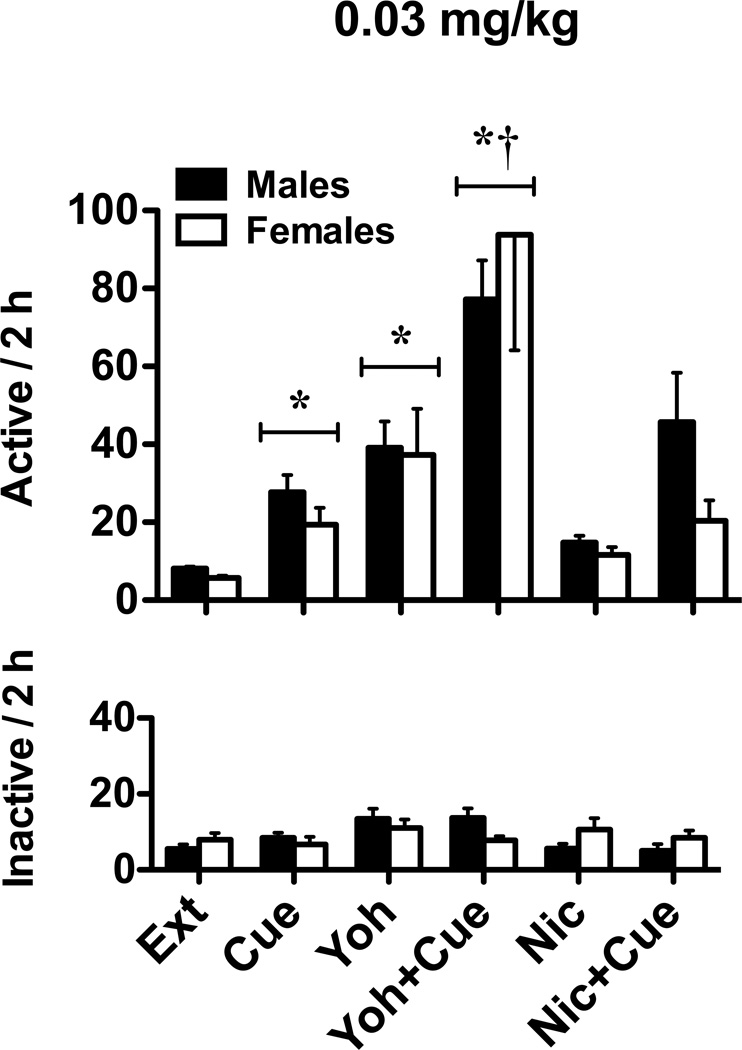

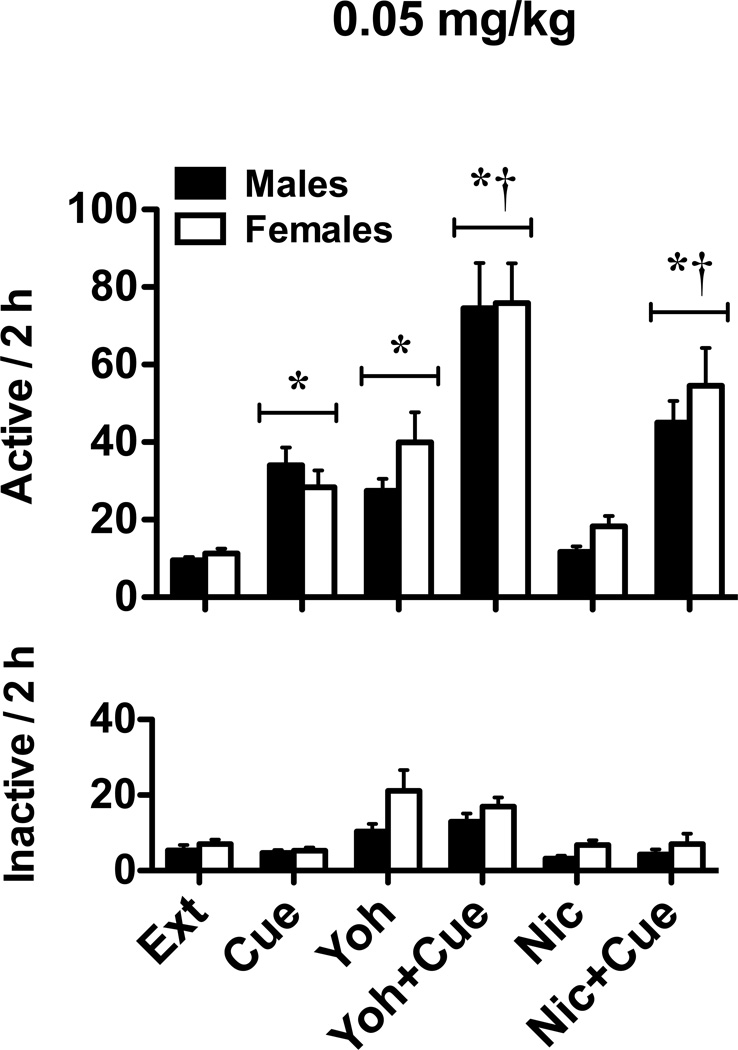

Compared to the no-cue-vehicle condition (i.e., extinction level responding), cue-induced reinstatement resulted in 3–4 times higher responding for both males and females in both nicotine groups (Figs. 4 and 5). Similar increases were noted when animals experienced yohimbine stress-induced reinstatement, but not the nicotine-prime. However, when combined with the previously nicotine-paired cues, yohimbine (both groups) and the nicotine-prime (0.05 mg/kg group) enhanced reinstatement responding. A 2 × 2 × 3 ANOVA of active lever responding for the 0.03 mg/kg group (Fig. 4) revealed significant main effects for cue (F1,267 = 22.60, p < 0.001) and drug (F2,267 = 26.35, p < 0.001), as well as a significant cue by drug interaction (F2,267 = 2.97, p = 0.05). The sex main effect and all other interactions were not significant. Relative to extinction level responding, post hoc analyses revealed significant cue and yohimbine reinstatement (relative to extinction level responding), as well as a significant potentiation in cue-induced reinstatement when cues were combined with yohimbine pretreatment (ps < 0.05). Similar analyses for the 0.05 mg/kg group (Fig. 5) showed significant main effects for cue (F1,292 = 79.59, p < 0.001) and drug (F2,292 = 31.83, p < 0.001), as well as a significant cue by drug interaction (F2,292 = 3.05, p < 0.05). The sex main effect and all other interactions were not significant. Moreover, post hoc analyses revealed significant cue and yohimbine reinstatement (relative to extinction level responding), as well as a significant increase in cue-induced reinstatement when cues were combined with yohimbine or nicotine prime (ps < 0.05). Finally, when reinstatement was examined across the different phases of the estrous cycle for both nicotine self-administration groups, 2 × 3 × 3 ANOVAs revealed significant main effects for cue (Fs1,115–151 = 5.17–30.91, ps < 0.05) and drug (Fs2,115–151 = 9.36–18.28, ps < 0.001). However, the estrous cycle main effects and all interactions were not significant.

Fig. 4.

Reinstatement of extinguished nicotine-seeking in male and female rats in the 0.03 mg/kg groups. Active (top) and inactive (bottom) lever responses (mean ± SEM) are shown following vehicle, yohimbine, or nicotine pretreatment prior to “no cue” (Ext, Yoh, and Nic, respectively) or “cue” (Cue, Yoh+Cue, and Nic+Cue, respectively) reinstatement tests. Significant reinstatement (*p<0.05) and enhancement of “cue” reinstatement (†p< 0.05) are indicated.

Fig. 5.

Reinstatement of extinguished nicotine-seeking in male and female rats in the 0.05 mg/kg groups. Active (top) and inactive (bottom) lever responses (mean ± SEM) are shown following vehicle, yohimbine, or nicotine pretreatment prior to “no cue” (Ext, Yoh, and Nic, respectively) or “cue” (Cue, Yoh+Cue, and Nic+Cue, respectively) reinstatement tests. Significant reinstatement (*p<0.05) and enhancement of “cue” reinstatement (†p< 0.05) are indicated.

4. Discussion

To date, very few studies have examined potential sex differences and the role of the estrous cycle in preclinical models of nicotine addiction, and have primarily focused on the time of active nicotine self-administration (Chaudhri et al., 2005; Donny et al., 2000; Lynch, 2009). In addition to examining nicotine self-administration, the current study characterized reinstatement of extinguished nicotine-seeking following prolonged withdrawal in both male and female rats. Although we did not find substantial sex differences or estrous cycle effects, the current study produced several novel findings. Our results showed that the anxiogenic drug, yohimbine, reinstated nicotine-seeking in both sexes. Moreover, while the previously nicotine-paired cues led to a similar level of nicotine-seeking (i.e., 3–4 times over extinction level responding), combining these stimuli resulted in substantial enhancement in nicotine-seeking (i.e., 9–15 times over extinction level responding) in both males and females. Finally, while the nicotine-prime alone was not effective at inducing reinstatement, a significant enhancement in cue-induced reinstatement was noted when both these stimuli were combined.

Although nicotine self-administration in rodents has been demonstrated in a number of laboratories (see Le Foll and Goldberg, 2009 for review), very few have examined this behavior in females. In addition to studies in adolescent mice (Klein et al., 2004) and rats (Lynch, 2009), only two studies to date have assessed nicotine self-administration in both males and females (Chaudhri et al., 2005; Donny et al., 2000). Similar to these findings, we noted robust levels of responding and nicotine intake in both sexes. Although there was some evidence of enhanced motivation for nicotine in females in previous studies, this was only noted under conditions requiring higher behavioral output (i.e., FR5 or PR schedules of reinforcement). That is, when self-administration was examined under a similar FR1 schedule of reinforcement (albeit in the absence of drug-paired stimulus; Chaudhri et al., 2005) or as a function of nicotine intake (Donny et al., 2000), no sex differences were noted. Although Chaudhri et al. (2005) noted some sex differences in nicotine intake at a dose similar to the current study (i.e., 0.06 mg/kg), this finding was likely due to the relatively higher intake in females (i.e., around 1.25 mg/kg in a 1-h session, versus 1.5 mg/kg in a 2-h session for our study). This difference may be partly due to greater nicotine intake in females within the first hour, as it has been shown across a variety of doses and schedules of reinforcement that the latency for females to take their first infusion is significantly less than that of males (Donny et al., 2000).

Interestingly, while no differences in nicotine intake were found at either self-administration dose, animals in the 0.03 mg/kg group did not increase their intake to compensate for the lower unit dose. Similar findings have been previously reported, including extended nicotine access paradigms (i.e., ≥ 23 h; DeNoble and Mele, 2006; O'Dell et al., 2007), with similar dosing regimens yielding comparable total intake (i.e., 0.2–1.5 mg/kg) values (Chaudhri et al., 2005; Donny et al., 1995; O'Dell et al., 2007; Paterson and Markou, 2004). Importantly, these values fall within daily nicotine intake levels reported for human smokers (i.e., 0.14–1.14 mg/kg; Benowitz and Jacob, 1984), further supporting the clinical relevance of nicotine self-administration studies.

Despite several studies that have reported cue (LeSage et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2006) and footshock stress (Buczek et al., 1999; Martin-Garcia et al., 2009; Yamada and Bruijnzeel, 2011; Zislis et al., 2007) induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking in male rats, our findings are unique in showing stress-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking by yohimbine. Moreover, combining the previously nicotine-paired cues and yohimbine resulted in a robust enhancement in nicotine-seeking. Exposure to a stressor has been shown to potentiate cue-induced reinstatement of ethanol- (Liu and Weiss, 2002), heroin- (Banna et al., 2010), and cocaine-seeking (Buffalari and See, 2009, 2011; Feltenstein et al., 2011; Feltenstein and See, 2006). The fact that stress enhancement of cue reactivity occurs with nicotine-seeking suggests that mechanisms of relapse in nicotine addiction likely share common substrates with other drugs of abuse, perhaps through structures such as the bed nucleus of stria terminalis, which mediates stress+cue reinstatement of cocaine-seeking (Buffalari and See, 2011).

One unexpected finding of this study was the inability for the nicotine-prime alone to reinstate nicotine-seeking. However, the overall reported magnitude of this effect is weak when compared to other drugs of abuse, such as cocaine and heroin (McFarland and Kalivas, 2001; Rogers et al., 2008; Schmidt et al., 2005), with variability reported both within and between nicotine studies that have employed similar procedures (O'Connor et al., 2010; Shaham et al., 1997; Shoaib, 2008). Several experimental differences may explain this discrepancy (e.g., dose, injection-to-test interval, route of administration, etc.) (Fattore et al., 2009; Le et al., 2006; Lindblom et al., 2002; Shram et al., 2008), including the particular rat strain used. Indeed, a recent study also failed to find nicotine-primed reinstatement in Sprague-Dawley rats, although nicotine enhanced cue-induced reinstatement (Clemens et al., 2010), an effect consistent with both the current study and others (O'Connor et al., 2010; Shoaib, 2008). A nicotine-prime may increase general attention or may specifically enhance the incentive saliency of the cues. Similar to other drugs of abuse (Robbins, 1976), it has been shown that nicotine enhances responsiveness to a conditioned reinforcer (Olausson et al., 2004). Given the critical role of cues in nicotine reinforcement (Caggiula et al., 2002; Chaudhri et al., 2005), these results collectively suggest that increased cue-induced reinstatement after a nicotine prime likely involves an augmentation in conditioned reinforcement.

In the present study, male and female rats both demonstrated similar and robust levels of responding and intake during nicotine self-administration. Following extinction of responding in the absence of nicotine reinforcement, exposure to the previously nicotine-paired cues or yohimbine, but not the nicotine-prime, reinstated nicotine-seeking similarly in both sexes. Moreover, yohimbine and nicotine (albeit under certain conditions for females) enhanced reinstatement when combined with nicotine-paired cues. However, our results suggest that sex differences and ovarian hormone cycles in nicotine addiction may be less prominent than those reported with other drugs of abuse (e.g., cocaine). Given the complex nature of nicotine addiction, future studies are warranted to further examine sex differences in nicotine-seeking under other environmental conditions (e.g., contextual relapse), as well as following self-administration conditions that may more closely model smoking behavior in humans (e.g., lower bolus doses of nicotine delivered slowly; Sorge and Clarke, 2009). Such studies may guide future treatment development targeted to tobacco dependence.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Cassandra Gipson for providing insightful comments. This research was supported by NIDA grant DA016511 (RES), NICHHD grant K12 HD055885-01 (MWF), and NIH grant C06 RR015455.

Role of funding source: The authors declare no role of the funding sources.

Footnotes

Contributors: MWF designed the experiments, assisted in the animal surgeries and the experimental procedures, performed statistical analyses, and wrote the manuscript. SMG performed the animal surgeries and experimental procedures. RES designed the experiment and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allen SS, Bade T, Center B, Finstad D, Hatsukami D. Menstrual phase effects on smoking relapse. Addiction. 2008;103:809–821. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Carroll ME. Sex differences in the effects of allopregnanolone on yohimbine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;107:264–267. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banna KM, Back SE, Do P, See RE. Yohimbine stress potentiates conditioned cue-induced reinstatement of heroin-seeking in rats. Behav. Brain. Res. 2010;208:144–148. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Jacob P., 3rd Nicotine and carbon monoxide intake from high-and low-yield cigarettes. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1984;36:265–270. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1984.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongiovanni M, See RE. A comparison of the effects of different operant training experiences and dietary restriction on the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2008;89:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Tiffany ST, Obremski KM, Baker TB. Postcessation cigarette use: the process of relapse. Addict. Behav. 1990;15:105–114. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90013-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczek Y, Le AD, Stewart J, Shaham Y. Stress reinstates nicotine seeking but not sucrose solution seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1999;144:183–188. doi: 10.1007/s002130050992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalari DM, See RE. Footshock stress potentiates cue-induced cocaine-seeking in an animal model of relapse. Physiol. Behav. 2009;98:614–617. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalari DM, See RE. Inactivation of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in an animal model of relapse: effects on conditioned cue-induced reinstatement and its enhancement by yohimbine. Psychopharmacology. 2011;213:19–27. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Chaudhri N, Perkins KA, Evans-Martin FF, Sved AF. Importance of nonpharmacological factors in nicotine self-administration. Physiol. Behav. 2002;77:683–687. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00918-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter MJ, Upadhyaya HP, LaRowe SD, Saladin ME, Brady KT. Menstrual cycle phase effects on nicotine withdrawal and cigarette craving: a review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2006;8:627–638. doi: 10.1080/14622200600910793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charney DS, Heninger GR, Redmond DE., Jr Yohimbine induced anxiety and increased noradrenergic function in humans: effects of diazepam and clonidine. Life Sci. 1983;33:19–29. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(83)90707-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Booth S, Gharib MA, Craven LA, Allen SS, Sved AF, Perkins KA. Sex differences in the contribution of nicotine and nonpharmacological stimuli to nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2005;180:258–266. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chornock WM, Stitzer ML, Gross J, Leischow S. Experimental model of smoking re-exposure: effects on relapse. Psychopharmacology. 1992;108:495–500. doi: 10.1007/BF02247427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens KJ, Caille S, Cador M. The effects of response operandum and prior food training on intravenous nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2010;211:43–54. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1866-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Redmond DE, Jr, Baraban JM. Noradrenergic agonists and antagonists: effects on conditioned fear as measured by the potentiated startle paradigm. Psychopharmacology. 1979;65:111–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00433036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNoble VJ, Mele PC. Intravenous nicotine self-administration in rats: effects of mecamylamine, hexamethonium and naloxone. Psychopharmacology. 2006;184:266–272. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0054-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Caggiula AR, Knopf S, Brown C. Nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1995;122:390–394. doi: 10.1007/BF02246272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Caggiula AR, Rowell PP, Gharib MA, Maldovan V, Booth S, Mielke MM, Hoffman A, McCallum S. Nicotine self-administration in rats: estrous cycle effects, sex differences and nicotinic receptor binding. Psychopharmacology. 2000;151:392–405. doi: 10.1007/s002130000497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dravolina OA, Zakharova ES, Shekunova EV, Zvartau EE, Danysz W, Bespalov AY. mGlu1 receptor blockade attenuates cue- and nicotine-induced reinstatement of extinguished nicotine self-administration behavior in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattore L, Spano MS, Cossu G, Scherma M, Fratta W, Fadda P. Baclofen prevents drug-induced reinstatement of extinguished nicotine-seeking behaviour and nicotine place preference in rodents. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19:487–498. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellows JL, Trosclair A, Adams EK. Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs: Uniter States, 1995–1999. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2002;51:300–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, Henderson AR, See RE. Enhancement of cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats by yohimbine: sex difference and role of the estrous cycle. Psychopharmacology. 2011;216:53–62. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2187-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, See RE. Potentiation of cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats by the anxiogenic drug yohimbine. Behav Brain Res. 2006;174:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC. Public health service clinical practice guideline: treating tobaco use and dependence. Respir. Care. 2000;45:1200–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forray MI, Bustos G, Gysling K. Regulation of norepinephrine release from the rat bed nucleus of the stria terminalis: in vivo microdialysis studies. J. Neurosci. Res. 1997;50:1040–1046. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19971215)50:6<1040::AID-JNR15>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TR, Napier K, Ehrman R, Gariti P, O'Brien CP, Childress AR. Retrospective study: influence of menstrual cycle on cue-induced cigarette craving. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2004;6:171–175. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Evans KA, Mehta RH, Case JM, See RE. Influence of sex and estrous cyclicity on conditioned cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2005;179:662–672. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass JT, Olive MF. Reinstatement of ethanol-seeking behavior following intravenous self-administration in Wistar rats. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2007;31:1441–1445. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon GE, Boisclair D. Past, current and future trends in tobacco use. Washington, DC.: World Bank; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg G, Gershon S. Autonomic and psychic effects of yohimbine hydrochloride. Psychopharmacologia. 1961;2:93–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00592678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenford SL, Fiore MC, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Wetter D, Baker TB. Predicting smoking cessation. Who will quit with and without the nicotine patch. JAMA. 1994;271:589–594. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.8.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshbouei H, Cecchi M, Dove S, Javors M, Morilak DA. Behavioral reactivity to stress: amplification of stress-induced noradrenergic activation elicits a galanin-mediated anxiolytic effect in central amygdala. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2002;71:407–417. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippin TE, Fuchs RA, Mehta RH, Case JM, Parker MP, Bimonte-Nelson HA, See RE. Potentiation of cocaine-primed reinstatement of drug seeking in female rats during estrus. Psychopharmacology. 2005;182:245–252. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0071-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein LC, Stine MM, Vandenbergh DJ, Whetzel CA, Kamens HM. Sex differences in voluntary oral nicotine consumption by adolescent mice: a dose-response experiment. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2004;78:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang WJ, Gershon S. Effects of psychoactive drugs on yohimbine induced responses in conscious dogs. A proposed screening procedure for anti-anxiety agents. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther. 1963;142:457–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Funk D, Shaham Y. Role of alpha-2 adrenoceptors in stress-induced reinstatement of alcohol seeking and alcohol self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2005;179:366–373. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2036-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Li Z, Funk D, Shram M, Li TK, Shaham Y. Increased vulnerability to nicotine self-administration and relapse in alcohol-naive offspring of rats selectively bred for high alcohol intake. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:1872–1879. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4895-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Wang A, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Shaham Y. Nicotine increases alcohol self-administration and reinstates alcohol seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:216–221. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1330-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, Goldberg SR. Effects of nicotine in experimental animals and humans: an update on addictive properties. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2009:335–367. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69248-5_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeSage MG, Burroughs D, Dufek M, Keyler DE, Pentel PR. Reinstatement of nicotine self-administration in rats by presentation of nicotine-paired stimuli, but not nicotine priming. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2004;79:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom N, de Villiers SH, Kalayanov G, Gordon S, Johansson AM, Svensson TH. Active immunization against nicotine prevents reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior in rats. Respiration. 2002;69:254–260. doi: 10.1159/000063629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Caggiula AR, Palmatier MI, Donny EC, Sved AF. Cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior in rats: effect of bupropion, persistence over repeated tests, and its dependence on training dose. Psychopharmacology. 2008;196:365–375. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0967-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Caggiula AR, Yee SK, Nobuta H, Poland RE, Pechnick RN. Reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior by drug-associated stimuli after extinction in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2006;184:417–425. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0134-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Weiss F. Additive effect of stress and drug cues on reinstatement of ethanol seeking: exacerbation by history of dependence and role of concurrent activation of corticotropin-releasing factor and opioid mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:7856–7861. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-07856.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ. Sex and ovarian hormones influence vulnerability and motivation for nicotine during adolescence in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2009;94:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcondes FK, Bianchi FJ, Tanno AP. Determination of the estrous cycle phases of rats: some helpful considerations. Braz. J. Biol. 2002;62:609–614. doi: 10.1590/s1519-69842002000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Garcia E, Barbano MF, Galeote L, Maldonado R. New operant model of nicotine-seeking behaviour in mice. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:343–356. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland K, Kalivas PW. The circuitry mediating cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:8655–8663. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08655.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor EC, Parker D, Rollema H, Mead AN. The alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine-receptor partial agonist varenicline inhibits both nicotine self-administration following repeated dosing and reinstatement of nicotine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2010;208:365–376. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1739-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dell LE, Chen SA, Smith RT, Specio SE, Balster RL, Paterson NE, Markou A, Zorrilla EP, Koob GF. Extended access to nicotine self-administration leads to dependence: Circadian measures, withdrawal measures, and extinction behavior in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007;320:180–193. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.105270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olausson P, Jentsch JD, Taylor JR. Nicotine enhances responding with conditioned reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 2004;171:173–178. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1575-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson NE, Markou A. Prolonged nicotine dependence associated with extended access to nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2004;173:64–72. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1692-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton D, Barnes GE, Murray RP. A personality typology of smokers. Addict. Behav. 1997;22:269–273. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA. Smoking cessation in women. Special considerations. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:391–411. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA. Sex differences in nicotine reinforcement and reward: influences on the persistence of tobacco smoking. Nebr. Symp. Motiv. 2009;55:143–169. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78748-0_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Donny E, Caggiula AR. Sex differences in nicotine effects and self-administration: review of human and animal evidence. Nicotine Tob. Res. 1999;1:301–315. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Grobe JE, Fonte C, Goettler J, Caggiula AR, Reynolds WA, Stiller RL, Scierka A, Jacob RG. Chronic and acute tolerance to subjective, behavioral and cardiovascular effects of nicotine in humans. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;270:628–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel CM, Moussawi K, Do PH, Kalivas PW, See RE. Chronic N-acetylcysteine during abstinence or extinction following cocaine self-administration produces enduring reductions in drug-seeking. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011;337:487–493. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.179317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW. Relationship between reward-enhancing and stereotypical effects of psychomotor stimulant drugs. Nature. 1976;264:57–59. doi: 10.1038/264057a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JL, Ghee S, See RE. The neural circuitry underlying reinstatement of heroin-seeking behavior in an animal model of relapse. Neuroscience. 2008;151:579–588. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt HD, Anderson SM, Famous KR, Kumaresan V, Pierce RC. Anatomy and pharmacology of cocaine priming-induced reinstatement of drug seeking. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2005;526:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Adamson LK, Grocki S, Corrigall WA. Reinstatement and spontaneous recovery of nicotine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1997;130:396–403. doi: 10.1007/s002130050256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard JD, Bossert JM, Liu SY, Shaham Y. The anxiogenic drug yohimbine reinstates methamphetamine seeking in a rat model of drug relapse. Biol. Psychiatry. 2004;55:1082–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Mason KM, Henningfield JE. Tobacco dependence treatments: review and prospectus. Annu. Rev. Publ. Health. 1998;19:335–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoaib M. The cannabinoid antagonist AM251 attenuates nicotine self-administration and nicotine-seeking behaviour in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shram MJ, Funk D, Li Z, Le AD. Nicotine self-administration, extinction responding and reinstatement in adolescent and adult male rats: evidence against a biological vulnerability to nicotine addiction during adolescence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:739–748. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Mouratidis M, Yoo S, Culligan K, Kosten T. Effects of tiagabine in combination with intravenous nicotine in overnight abstinent smokers. Psychopharmacology. 2005;181:504–510. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0010-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorge RE, Clarke PB. Rats self-administer intravenous nicotine delivered in a novel smoking-relevant procedure: effects of dopamine antagonists. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;330:633–640. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.154641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine SM, Southwick SM, Petrakis IL, Kosten TR, Charney DS, Krystal JH. Yohimbine-induced withdrawal and anxiety symptoms in opioid-dependent patients. Biol. Psychiatry. 2002;51:642–651. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suemaru S, Dallman MF, Darlington DN, Cascio CS, Shinsako J. Role of alpha-adrenergic mechanism in effects of morphine on the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical and cardiovascular systems in the rat. Neuroendocrinology. 1989;49:181–190. doi: 10.1159/000125112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thun MJ, da Costa e Silva VL. Introduction and overview of global tobacco surveillance. In: Shafey O, Dolwick S, Guindon GE, editors. Tobacco Control Country Profiles. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2003. pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H, Bruijnzeel AW. Stimulation of alpha2-adrenergic receptors in the central nucleus of the amygdala attenuates stress-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zislis G, Desai TV, Prado M, Shah HP, Bruijnzeel AW. Effects of the CRF receptor antagonist D-Phe CRF(12–41) and the alpha2-adrenergic receptor agonist clonidine on stress-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:958–966. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]