Abstract

Gardner's Syndrome is a variant of familial adenomatosis polyposis (FAP) with a triad consisting of polyps of the colon, multiple osteomas and surface tumors of soft and hard tissue. The intestinal polyps have a %100 risk of undergoing malignant transformation, therefore early identification of this disease is very important. There are several symptoms of Gardner's syndrome in the oral and maxillofacial surgery, which can be discovered during routine dental examination. We report a case of a 25-year old male patient with Gardner's syndrome who has not any intestinal polyps but osteomas in the mandible and jaw deformalities.

Keywords: Gardner's syndrome, jaw, dental deformalities

Introduction

Gardner's syndrome (GS) is an autosomal dominant disorder localized to a small region on the long arm of chromosome 5 (5q21-22).1,2,3 Menzel first described adenomatosis of the colon in 1721, and in 1863, Cripps discovered the heredity of colon polyposis and termed it familial adenomatosis.4 Devic and Bussy in 1912 described a triad of intestinal polyps, soft tissue tumors, and multiple osteomas of the skull.5 In 1943 Fitzgerald described a case of intraosseous osteomas, abdominal desmoids, and multiple colon polyposis and defined the oral and facial aspects of the disease.6,7 In the early 1950s, the syndrome was defined by Gardner. In 1962, he also discovered the dental abnormalities and skeletal alterations of these patients.8

Oral and facial anomalies are commonly observed in patients affected with this disease complex, and intestinal polyps predominantly cause malignancy. Dentists should be aware that oral and facial anomalies may play an important role in the early diagnosis of GS. This article presents a case of GS and briefly reviews the oral and maxillofacial considerations of this disease.

Case

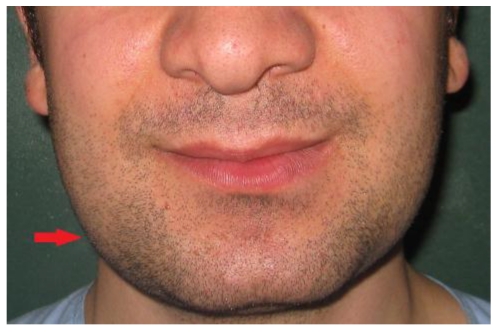

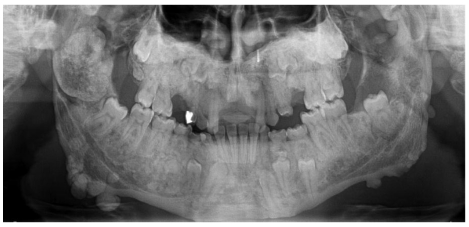

A 21-year-old patient was referred to the Department of Oral Surgery at Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey, for the management of craniofacial manifestations of GS. Intra-oral, extra-oral, and radiological examinations were performed. The patient came to our attention due to a primarily esthetic complaint about the right angle of the mandible. An initial clinical examination showed a nodular formation that was palpable along the mesial portion of the right mandibular angle (Figure 1). The oral mucosa was normal, and the regional lymph nodules were not palpable. A panoramic radiograph and an anteroposterior radiography showed the presence of multiple round radiopaque lesions in both the maxilla and mandible, multiple impacted teeth (upper right first, second premolar, upper right third molar, upper left canine, upper left first and second premolar, upper third molar, lower left canine, first and second premolar, and lower right canine, first and second premolar), and multiple odontomas, each measuring approximately 0.5 to 2 cm in diameter (Figure 2). On palpation, these lesions were hard, well limited, and non-adherent to the skin. Diffuse sclerosis could also be noted throughout the mandibular body. Neither crepitating nor clicking on mouth opening was noticed in the temporomandibular region bilaterally. Maximum mouth opening was not restricted (42 mm). No deviation of the mandible was observed, and no pain on mouth opening was evident. No trigeminal paresthesia was diagnosed, and the facial nerve function was preserved.

Figure 1.

Front view of the patient's lower face.

Figure 2.

Panoramic view of the patient presenting multiple osteomas. A particularly large lobulated osteoma is present in the right condyle and coronoid process that impacted both permanent and deciduous teeth.

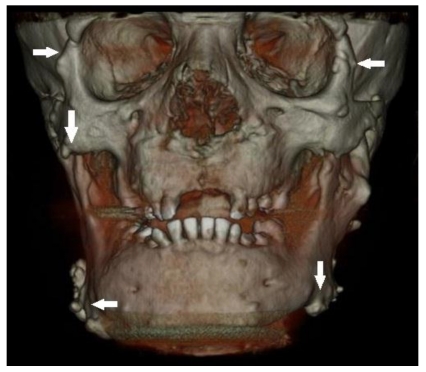

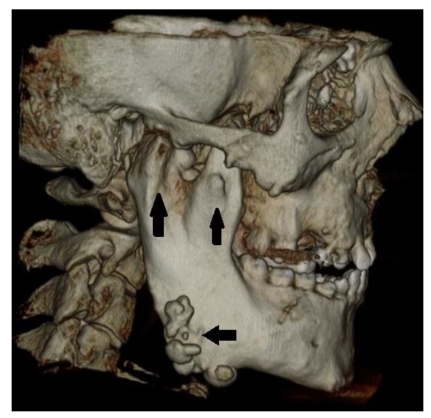

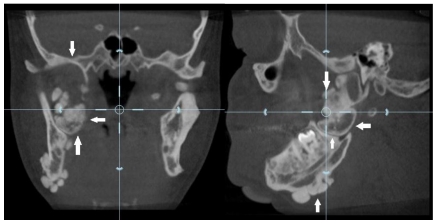

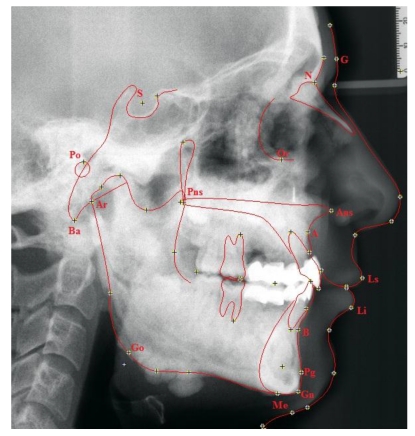

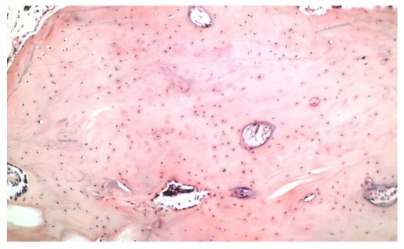

Dental volumetric tomographic (DVT) images showed multiple osteomas of the buccal cortex of the right mandibular angle and left mandibular angle (Figure 3,4). Additionally, in the coronal and sagittal sections of the mandible condyle, a huge osteoma that limited mouth opening was diagnosed (Figure 5). Cephalometrically, he showed a slightly retrusive maxilla with an ANB angle of 1˚and a relatively normal mandibula in anterioposterior direction. His mandibular plane angle (S-N / Go-Me: 25˚) and articular angle (S-Ar-Go: 133˚) were reduced (Table 1). His profile was straight due to the slightly retruded maxilla position. According to the Steiner's S line his lips were in normal position (Figure 6). The osteomas were submitted for pathologic examination. Histopathologic examination revealed that the specimens displayed a normal-appearing dense compact lamellar bone with minimal marrow spaces and rare irregular Haversian canals that did not show osteoclasts or osteoblasts (H&E X100)(Figure 7). Due to the dental anomalies, the osteomas in the mandible and the familial history of the patient, the patient was diagnosed as GS. Following resection of the osteomas that caused discomfort, prosthetic rehabilitation was performed.

Figure 3.

Osteomas at the left mandible angulus, mental protuberance and below the mandibular notch (white arrows)

Figure 4.

Osteomas at the right mandible angulus and also both condyle and coronoid process deformities (black arrow)

Figure 5.

Coronal and sagittal section view of the right condyle showing large lobulated osteoma (white arrows)

Table 1.

Measurement of the internal cranial structures

| Skeletal Measurements | Normal Value | Patient's Value |

|---|---|---|

| SNA | 82 | 80 |

| SNB | 79 | 79 |

| ANB | 3 | 1 |

| A - B(OP) | -1 | 0 |

| Npog-FH (Facial plane) | 85 | 89 |

| S-Ar-Go | 143 | 133 |

| Ar-Go-Gn | 130 | 126 |

| S-N/Go-Me | 32 | 25 |

| S-N-Gn(Y axis) | 67 | 68 |

Figure 6.

Tracing lateral cephalometric radiograph of the patient. Ricketts' analysis is illustrated. G = glabella; N = the anterior point of the intersection between the nasal and the frontal bones; Or = the lowest point of the inferior margin of the orbi; Pn = pronasale; Po = the midpoint of the upper contour of the external auditory canal; Pns = posterior nasal spine; Ans = anterior nasal spine; A = the innermost point on the contour of the premaxilla between anterior nasal spine and the incisor tooth; Pg = the most anterior point on the contour of the chin; Gn = the most anterior and inferior point on the mandibular symphysis; Me = the most inferior point on the mandibular symphsis; Go = the midpoint of the contour connecting the ramus and body of the mandible; Ba = the lowest point on the anterior margin of the foramen magnum, at the base of the clivus; Ar = the point of the intersection between the shadow of the zygomatic arch and posterior border of the mandibular ramus.

Figure 7.

Compact tissue within a loose connective tissue containing apposition and resorption lines(X100, H&E).

Discussion

Gardner's syndrome is inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder with an incidence ranging between 1 in 4,000 and 1 in 12,000, depending on the region.5,9 GS is known to be caused by a gene mutation located at chromosome 5.10 The patient in this study displayed a familial history of the disease; the mother and sister had both died due to GS.

The intestinal polyps of the disease typically occur prior to puberty and become generalized in the 20-40-year age group. The polyps display the potential for malignant change.3,6 These multiple polyps can be observed at any location in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly in the distal colon, and must be completely removed due to the high rate of transformation to adenocarsinoma.6 Gastric fundic polyps occur in 90% of affected individuals, but they are not malign lesions. Duodenal polyps also occur in 90% of affected individuals. Large polyps can cause intestinal bleeding, intussusception, or intestinal blockage. They are premalignant lesions for periampullary carcinoma.2,6 An increased number of peptic ulcers have also been observed.8

Soft-tissue lesions such as fibromas, neurofibromas, keloids, sebaceous cysts, leiomyomas, and lipomas are also observed.8 Desmoid tumors are considered locally invasive, non-malignant, and non-encapsulated and may occur in the skin of the anterior abdominal wall or intra-abdominally. They display no malignant potential and have a slow growth pattern.2,3,6 These lesions occur in approximately 10% of patients and are three times more common in women.11 The majority of cutaneous lesions observed in GS present as multiple epidermoid cysts on the face, scalp, and extremities. They are benign lesions that occur at an early age, around puberty.3,6 Other neoplasias such as papillary carcinoma, adrenal adenoma, adenocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, osteochondroma, tiroid tumors, liver tumors, and less commonly, hypertrophy of the pigment layer of the retina have also been reported.12

Dental abnormalities are present in 30-75% and osteomas in 68-82% of GS patients. The osteotomas are generally located in the paranasal sinuses and mandible, display slow growth, and vary from a slight thickening to a large mass.13 Osteomas predominantly affect the mandible and maxilla5,12 but can additionally affect the skull and long bones. Calvarium osteomas, maxillary osteomas, and hypercementosis also occur.14 Osteomas are an essential component of GS, forming a slight thickening to a large mass that may affect all parts of the skeleton. The frontal bones are the most frequent osteoma site.6 Exosteoses osteomas, also called peripheral osteomas, and enosteoses osteomas can be palpable, and enostoses may be detected by routine radiography.3,6 In the mandible, two types of osteomas occur: central or lobulated. Centrally located osteomas are characteristically near the roots of the teeth, and lobulated types arise from the cortex and most commonly observed at the mandibular angle.6 We saw a huge lobulated osteoma at the right condyle and many central osteomas throught both maxilla and mandible.

Seventy percent of GS patients display dental anomalies such as impacted or unerupted teeth, congenitally missing teeth, supernumerary teeth, hypercementosis, dentigerous cysts, fused molar roots, long and tapered molar roots, hypodontia, compound odontomes, and multiple caries.3,5 Difficulties in extraction due to ankylosis have also been reported.6

Our patient presented several dental abnormalities including multiple impacted teeth in the mandible and maxilla and osteomas throughout the mandible, maxilla, and both condyle and coronoid processes.

Osteomas are predominantly detected by routine panoramic radiography.15 Pain is rarely observed, and the disease is predominantly asymptomatic, but the lesions can cause facial asymmetry as a result of expansion.13 In addition to clinical palpation, dental panoramic radiography is an effective means of detecting multiple osteomas of the jaws that are characteristic of GS. Radiologically, the lesions are radio-opaque. In our patient, radio-opacities on the angle of the mandible were observed, and several impacted teeth in all segments of the jaws were evident. Increased difficulty of tooth extraction was present due to the high density of the alveolar bone, the limited mouth opening, and the loss of the periodontal space.16 Our diagnosis was performed by CT radiographs to detect osteomas and dental anomalies.

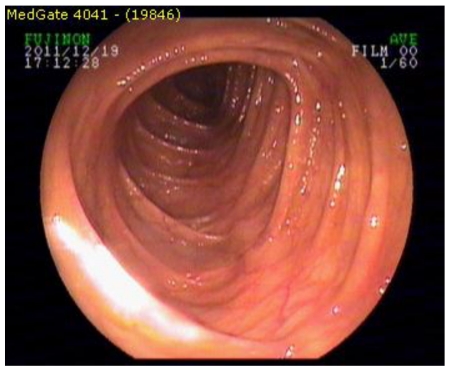

In conclusion this case demonstrated the characteristic oral and maxillofacial features of GS, but the patient displayed no signs of intestinal polyps or cutaneous lesions. We report this case due to the absence of intestinal polyps, a rare occurrence in GS patients. According to Lew, 90% of affected patients display intestinal polyps. In contrast, the oral and maxillofacial manifestations of this syndrome appear many years prior to the intestinal lesions, meaning our patient may present intestinal polyps in the future. Osteomas that limit mandibular movement or cause esthetic problems were removed, but the possibility of recurrence exists. In such situations, the maxillofacial surgeon must perform an early GS diagnosis. The patients should always be in contact with a gastroenterologist, an oncologist, and an oral surgeon

Figure 8.

Endoscopic examination revealed an intact intestinal mucosa without any polyps.

References

- 1.Bodmer WF, Bailey EJ, Bodmer J. et al. Localization of the gene for familial adenomatous polyposis on chromosome 5. Nature. 1987;328:614. doi: 10.1038/328614a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lew D, DeWitt A, Hicks RJ, Cavalcanti MGP. Osteomas of the condyle associated with Gardner's syndrome causing limited mandibular movement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:1004–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(99)90026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler J, Healy C, Toner M, Flint S. Gardner's syndrome—review and report of a case. Oral oncology Extra. 2005;41:89–92. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dolan KD, Seibert J, Seibert RW. Gardner's syndrome. A model for correlative radiology. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1973;119(2):359–64. doi: 10.2214/ajr.119.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madani M, Madani F. Gardner's syndrome presenting with dental complaints. Arch Iranian Med. 2007;10(4):535–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wesley RK, Cullen CL, Bloom WS. Gardner's syndrome with bilateral osteomas of coronoid process resulting in limited opening. Pediatr Dent. 1987;9(1):53–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzgerald GM. Multiple composite odontomas coincidental with other tumorous conditions: Report of a case. J Am Dent Assoc. 1943;30:1408. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Small IA, Shandler H, Husain M, David H. Gardner's syndrome with an unusual fibro-osseous lesion of the mandible. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral Pathology. 1980;49(6):477–486. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(80)90066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basaran G, Erkan M. One of the rarest syndromes in dentistry: Gardner's syndrome. European Journal of Dentistry. 2008;2:208–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee BD, Lee W, Oh SH, Min SK, Kim EC. A case report of Gardner's syndrome with hereditary widespread osteomatous jaw lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(3):e68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jagelman DG. Manifestations of familial polyposis coli. Cancer Genet Cytogene. 1987;27:319. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(87)90014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawlatly EE, Al-Qurain AA, Salih-Mahmut M. Gardner's syndrome presenting with a giant osteoma. Ann Saudi Med. 1997;17(5):542–4. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1997.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones EL, Corell WP. Gardner's syndrome. Arch Surg. 1966;92:287–299. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1966.01320200127020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boffano P, Bosco GF, Gerbino G. The surgical management of oral and maxillofacial manifestations of Gardner's syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2549–2554. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.09.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramaglia L, Morgese F, Filippella M, Colao A. Oral and maxillofacial manifestations of Gardner's syndrome associated with growth hormone deficiency: case report and literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(6):e30–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]