Abstract

TGFβ1 was initially identified as a potent chemotactic cytokine to initiate inflammation, but the autoimmune phenotype seen in TGFβ1 knockout mice reversed the dogma of TGFβ1 being a pro-inflammatory cytokine to predominantly an immune suppressor. The discovery of the role of TGFβ1 in Th17 cell activation once again revealed the pro-inflammatory effect of TGFβ1. We developed K5.TGFβ1 mice with latent human TGFβ1 overexpression targeted to epidermal keratinocytes by keratin 5. These transgenic mice developed significant skin inflammation. Further studies revealed that inflammation severity correlated with switching TGFβ1 transgene expression on and off, and genome wide expression profiling revealed striking similarities between K5.TGFβ1 skin and human psoriasis, a Th1/Th17-associated inflammatory skin disease. Our recent study reveals that treatments alleviating inflammatory skin phenotypes in this mouse model reduced Th17 cells, and antibodies against IL-17 also lessen the inflammatory phenotype. Examination of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines affected by TGFβ1 revealed predominantly Th1-, Th17-related cytokines in K5.TGFβ1 skin. However, the finding that K5.TGFβ1 mice also express Th2-associated inflammatory cytokines under certain pathological conditions raises the possibility that deregulated TGFβ signaling is involved in more than one inflammatory disease. Furthermore, activation of both Th1/Th17 cells and regulatory T cells (Tregs) by TGFβ1 reversely regulated by IL-6 highlights the dual role of TGFβ1 in regulating inflammation, a dynamic, context and organ specific process. This review focuses on the role of TGFβ1 in inflammatory skin diseases.

Keywords: TGFβ1, skin inflammation

Introduction

Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) is a multipotent cytokine consisting of TGFβ1, 2, and 3, with TGFβ1 being the most abundant isoform in most tissues, including the skin. Smad2 and Smad3 are phosphorylated once TGFβ binds to receptors I and II. Phosphorylated Smads bind with Smad4 to form heteromeric complexes, translocate to the nucleus and transcriptionally regulate TGFβ responsive genes 1. TGFβ1 is secreted in a biologically latent form and becomes activated when mature TGFβ1 disassociates from its latency associated peptide dimer. TGFβ1 is a very potent stimulator of chemotaxis; TGFβ1 stimulates migration of monocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils and fibroblasts with 10-15 M concentrations 2. There are several animal models study the effects of TGFβ1. TGFβ1 knockout mice die from multifocal inflammation and autoimmune disorders in internal organs, suggesting its immune suppressive effect in these organs 3, 4. However, TGFβ1 knockout mice lack Langerhans cells, which require TGFβ1 for development and activation, and therefore do not have skin inflammation 5, 6. Furthermore, overexpression of TGFβ1 in the epidermis of K5.TGFβ1 mice (latent human TGFβ1 overexpression targeted to epidermal keratinocytes by keratin 5) results in significant skin inflammation 7, whereas their internal organs are protected from inflammation and autoimmune diseases by elevated systemic levels of TGFβ1 secreted by K5.TGFβ1 keratinocytes 8. In vitro cultured keratinocytes isolated from these transgenic mice still exhibit the growth inhibitory effect of TGFβ1, suggesting that epidermal hyperplasia is mainly due to indirect effects of TGFβ1-initiated inflammation, fibroblast hyperproliferation and angiogenesis 7. The inflammatory effect of TGFβ1 on skin has been further confirmed with inducible TGFβ1 transgenic mice, where studies have shown inflammation is correlated with TGFβ1 expression 9, 10. The significance of TGFβ1 overexpression mediating skin inflammation in our mouse model is further highlighted by a recent study showing that genome wide expression profiling in K5.TGFβ1 skin is strikingly similar to that in human psoriasis 11.

IL-23/Th17 pathway is involved in TGFβ-mediated skin inflammation

The role of T cells in the development of psoriasis was identified 20 years ago. Psoriasis was considered a Th1-associated autoimmune disease until the identification of Th17 cells 12-14. Recent studies indicate that Th17 cells and their upstream stimulator IL-23, or the IL-23/Th17 pathway, play crucial roles in the pathogenesis of several autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis 14-16. Th17 cells differentiate from naïve T cells and are distinct from Th1 and Th2 cells. Studies suggest TGFβ1 and IL-6 are required for mouse Th17 cell differentiation from naïve CD4+ T cells 17-19. In humans, the presence of TGFβ1 significantly increases Th17 cell differentiation, although it is still an ongoing debate if TGFβ1 is absolutely required 12, 15, 20, 21.

IL-23 is a heterodimeric cytokine consisting of IL-23p19 and IL-12p40 subunits. Many cell types, including monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, T cells and keratinocytes, have been shown to express IL-23 12, 22-24. The IL-23 receptor (IL-23R) consists of the heterodimer that binds to the IL-23p19 subunit and the IL-23/IL-12p40 subunit. IL-23R has been found on activated and memory T cell populations, but not naïve T cells 25-27. IL-6 and TGFβ1 were shown to induce IL-23R expression. Although IL-23 may not be involved in the differentiation of Th17 cells from naïve T cells, it plays a key role in the maintenance of Th17 cells, and promotes Th17 cells to be more terminally-differentiated and pro-inflammatory 26. Abnormal expression of IL-23 has also been linked to the pathogenesis of autoimmune inflammation. Further studies showed IL-23 regulates its target genes through activation of STAT3 12, 27. Based on current studies, Th17 cell differentiation from naïve T cells requires TGFβ1 and IL-6, but full and sustained differentiation of Th17 cells also requires IL-23 and IL-1β 12, 21, 26. Increased IL-23 expression has been found in psoriatic skin lesions 28, 29. A genomewide association study (GWAS) also reveals an association between psoriasis and the IL-23 and NF-κB pathways 30. Furthermore, antibodies against the IL-23/IL-12 p40 subunit are effective treatments for human psoriasis patients 31-35. These findings led to the hypothesis that IL-23 is involved in human psoriasis. This notion is further supported by experimental therapeutics showing efficacy of the monoclonal antibody against the IL-23p19 subunit to treat mice with xenografted human psoriasis lesions 36. Therefore, it is currently accepted that activation of Th17 cells, with or without Th1 cells, contributes to the pathogenesis of human psoriasis 37-41.

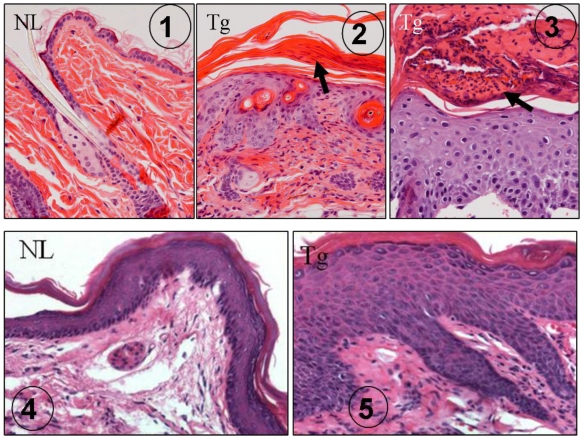

Several earlier reports indicated that TGFβ1 was abnormally expressed in human psoriasis 42-45. In our K5.TGFβ1 mice, TGFβ1 causes significant skin inflammation recapitulating most features of human psoriasis: scaly and erythematous plaques in the skin grossly 7 and histologically epidermal hyperplasia, leukocyte infiltration in the dermis and/or in the upper layer of the epidermis forming subcorneal microabscesses (Fig. 1) 7. In the foot pad where the thickness of the epidermis is comparable to human skin, rete ridge (down growth of the epidermis) is obvious in K5.TGFβ1 skin (Fig. 1). The causal role of TGFβ1 in skin inflammation in mice was further confirmed by our subsequent study using a gene-switch-TGFβ1 mouse model 9. In this mouse model, temporal TGFβ1 induction resulted in skin inflammation, which abated when TGFβ1 induction was halted 9. Based on the K5.TGFβ1 transgenic mouse model, we reported that molecular mechanisms underlying TGFβ1-induced skin inflammation could be attributed to Th1-type cytokines in the skin 7.

Fig 1.

K5.TGFβ1 skin exhibits psoriasis-like histopathology. ① H&E staining of dorsal skin in normal wild type mouse (NL), which is significantly thinner than human epidermis. ② H&E staining of dorsal skin in K5.TGFβ1 transgenic mouse (Tg) showing epidermal hyperplasia, infiltrated leukocytes in the dermis and parakeratosis (arrow). ③ Subcorneal microabscesses (arrow) formed in the dorsal skin of K5.TGFβ1 transgenic mouse (Tg). ④ Foot pad skin from a normal wild type mouse (NL) showing epidermal thickness comparable with human epidermis. ⑤ Foot pad skin of a K5.TGFβ1 transgenic mouse (Tg) showing significant epidermal hyperplasia and downward growth of the epidermis forming rete ridge structures with infiltrated leukocytes between them; the characteristics are similar to human psoriatic lesions.

It has been shown previously that CD4+CD25+Foxp3+-regulatory T cells (Tregs) from patients with psoriasis were dysfunctional in suppressing the proliferation of T responder cells 46 and over activation of the IL-23/Th17 pathway existed in human psoriasis 12. TGF-β is critical for generation of both Tregs and Th17 cells from naïve T cells 17, 47 whereas the presence of IL-6 inhibits the conversion of T cells into Foxp3+ Tregs and favors Th17 immunity 48, 49. The population of Tregs from lymph node cells or splenocytes of K5.TGFβ1 transgenic mice showed no difference in comparison with that from wild type mice 50. In vitro culture Tregs from both wild type and K5.TGFβ1 mice do not proliferate in response to polyclonal stimulation 50. However, Tregs from K5.TGFβ1 transgenic mice failed to suppress T responder cell proliferation during later stages of disease development and the dysfunction of Tregs has been restored in K5.TGFβ1 mice received 8-methoxypsoralen plus ultraviolet A therapy (PUVA) with downregulation of IL-6 50. Those results suggested increased IL-6 in K5.TGFβ1 mice play a crucial, suppressive role in TGFβ induced Tregs differentiation.

To further investigate if the IL-23/Th17 axis is involved in TGFβ1 induced skin inflammation, we studied how the IL-23/Th17 pathway is altered in K5.TGFβ1 mice. Compared to wild type mice, the numbers of IL-23p19 positive keratinocytes and stromal cells in the skin are significantly increased in K5.TGFβ1 50. Additionally, high levels of serum IL-17A, IL-17F and IL-23 were detected. IL-23p19 staining in dorsal skin and serum levels of IL-17 declined with the reduction of inflammation after treatment with PUVA 50. Further, platelet-activating factor (PAF), a potent biolipid mediator involved in psoriasis pathogenesis, also induces the IL-23/Th17 pathway; blocking PAF by its receptor antagonist results in a decrease of mRNA and/or protein levels of IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-23, IL-12A, and IL-6 in K5.TGFβ1 mice 51. Increased numbers of Th17 cells were also found in Smad4-deleted oral mucosa where endogenous TGFβ1 is overexpressed and signaling is mainly Smad3-dependent 52. These results strongly indicate IL-23/Th17 axis involvement in TGFβ1 mediated inflammation. Supporting this finding, Mohammed et al recently reported that temporally and acutely induced TGFβ1 overexpression in premalignant epidermal keratinocytes enhanced IL-17-producing cell populations in their Tet-inducible K5.TGFβ1 transgenic mouse model 10. Further analysis in their study showed CD4+ and γδ+ T cells secreted IL-17A upon TGFβ1 induction 10. Interestingly, TGFβ1 induction in cultured mouse keratinocytes pre-infected with v-rasHA resulted in increased IL-23p19 and IL-6 transcriptional expression dependent on autocrine TGFβ1 signaling. Conditioned media from the above cultured cells also caused IL-17A production in naïve T cells 10. Therefore, it is likely that TGFβ1, through induction of inflammatory cell- and keratinocyte-derived Th17-polarizing cytokines, contributes to the production of IL-17 in TGFβ1-induced inflammatory skin tissue (Fig.2) 7, 10, 12, 50. As IL-23 is primarily involved in maintaining Th17 effector cells and does not function on naïve T cells 26, using IL-23 antibody alone is insufficient to antagonize constitutive overexpression of TGFβ1-induced IL-17 production and therefore shows no effect on TGFβ1-induced inflammation (Fig. 2) 53. In contrast, directly targeting IL-17 with an IL-17 antibody treatment is effective in relieving skin inflammation in K5.TGFβ1 mice (Fig.2) 50.

Fig 2.

Schematic model depicts potential molecular mechanisms of IL23/Th17-mediated inflammation in K5.TGFβ1 skin. A. TGFβ1 is overexpressed in the epidermis of K5.TGFβ1 mice and released into, and activated in the dermis, where it attracts inflammatory cells. Inflammatory cells in cooperation with keratinocytes produce IL-23, IL-1β, IL-6 and other cytokines or chemokines in stroma. B. Th17 cells develop from naïve T cells in the presence of TGFβ1 and IL-6. IL-23, together with IL-1β act on activated/memory T cells to maintain Th17 cell activation. Anti-IL-23 antibody treatment on K5.TGFβ1 mice partially inhibits Th17 cell producing IL-17, but not enough to block TGFβ1-induced Th17 cell proliferation. Direct targeting IL-17 with anti-IL17 treatment has a more potent effect on relieving skin inflammation in K5.TGFβ1 mice.

Is TGFβ1 involved in Th2 cell mediated inflammatory skin diseases?

All K5.TGFβ1 transgenic mice develop skin inflammatory phenotypes during their lifespan, and visible skin inflammation manifests at around 2-months of age. The gross phenotype and histopathology largely mimics features of human psoriasis with dominant Th1 type cytokines in skin lesions 7. However, a subsequent report shows that K5.TGFβ1 mice also developed lesions and pathogenesis resembling human atopic dermatitis (AD), with high IL-4 expression and scattered eosinophils in lesional skin, and high-serum IgE levels 53. There are several possibilities to reconcile these apparently paradoxical findings. First, Th1 and Th2 inflammatory skin disorders are not always mutually exclusive. Skin barrier defects play an important role in AD 54. Similarly, a GWAS showed that gene deletion for the cornified envelope of the epidermis is linked to psoriasis susceptibility 16. Studies have shown that IL-17 produced by Th17 cells is also elevated in acute AD lesions, and the number of Th17 cells correlated with acute AD severity 55, 56. Psoriasis and late-phase AD in humans share many pathologic features 38, 57, and increased TGFβ1 has been found in both psoriasis 42, 45 and AD 55. Also, similar therapeutic approaches, e.g. corticosteroids, cyclosporine A and phototherapy, show clinical efficacy for both diseases 57, 58. This clinical evidence reflects an overlap of pathogenesis occurring in vivo between these two diseases. Second, TGFβ1 may also be involved in AD pathogenesis. TGFβ1 overexpression has been shown to cause infiltration of mast cells 7, which favor AD development 59, 60. Third, although psoriasis and AD usually have distinct Th1- and Th2-associated inflammatory cytokines, respectively, Th2 and Th1 cytokine profile shifts have also been observed in both AD and psoriasis 38, 61-63. The shift of cytokine profiles and pathological characteristics could happen in K5.TGFβ1 mice at different ages or in housing conditions where they are exposed to different environmental factors, especially under conditions where lesional skin barrier functions are severely compromised. For instance, the predominant Th2 cytokine profile found in one study 53 was not evident in other studies 50, 51 or in mice freshly re-derived in the SPF (Specific Pathogen Free) facility 7. Lastly, TGFβ1-mediated skin inflammation may be involved with more than Th1/Th2 diseases, as IL-17 antibody treatment or depletion of total T cells does not completely eliminate TGFβ1-induced inflammation or infiltration of other leukocyte types 9, 10, 50. Therefore, the effects of TGFβ on immune cell regulation are complex, and formation of inflammation may be affected by other factors such as the environment. Long term and parallel evaluation of the phenotype and its underlying pathogenesis in K5.TGFβ1 mice will advance our current understanding of the role of TGFβ1 in the skin inflammation, and help design new strategies for controlling human inflammatory disorders. In clinical practice, treatments in psoriasis and AD are largely different, while some common methods are used for symptom controls. If TGFβ1 proves to be involved in the pathogenesis of both diseases, inhibition of TGFβ1 or its downstream effectors may be explored as therapeutic strategies.

Experiments testing therapeutic approaches for TGFβ1-mediated skin inflammation in the K5.TGFβ1 mouse model

K5.TGFβ1 transgenic mice develop a stable and significant skin inflammation phenotype, thus this mouse model can be used for testing novel drugs and other strategies to control inflammatory diseases. For instance, we previously tested Enbrel, a psoriasis drug that inhibits the TNFα-NFκB pathway, in K5.TGFβ1 mice and found that it alleviates the skin inflammatory phenotype 9. Additionally, PUVA has been widely used as an alternative therapeutic approach for human psoriasis, especially for severe or widespread psoriasis. Our recent report indicated K5.TGFβ1 mice receiving PUVA treatment had significantly reduced skin inflammation 50. Further studies on the underlying mechanism suggested PUVA therapy, in addition to its possible direct anti-proliferative effects on keratinocytes 64, dramatically inhibited the IL-23/Th17 pathway in TGFβ1-induced inflammation. By analyzing immune alterations in skin and serum in K5.TGFβ1 mice before and after PUVA treatment, we found that several molecular components that lie upstream of Th17 activation signaling, including IL-23, ROR-γt and STAT3, were significantly reduced upon PUVA treatment. Consequently, populations of IL-17A- and IL-17F-producing CD4+ T cells in pooled splenocytes were decreased ~2 and ~6 fold, and IL-17A with IL-17F cytokine expression in skin was significantly reduced. In addition, PUVA treatment has also been found to regulate the Th1/Th2 cell shift in K5.TGFβ1 mice, characterized by inhibition of IFN-γ expression and induction of IL-10 in both serum and skin. Further studies indicated that TGFβ1-induced skin inflammation was blocked by anti-IL-17 mAb. These data verified the important role of the IL-23/Th17 axis in TGFβ1-induced skin inflammation and further validated this mouse model for testing therapeutic approaches against skin inflammation.

Future perspectives

Our K5.TGFβ1 transgenic mice provide a useful model in exploring the function of TGFβ1 in the formation of skin inflammation. To further understand which inflammatory skin diseases in humans involve TGFβ1-induced skin inflammation, levels of TGFβ1 and its signaling components in human diseases should be carefully examined. Unbiased cross-species comparisons of the pathological and molecular alterations between human diseases and K5.TGFβ1 mice should be performed. Similar to the study using whole-genome transcriptional profiling 11, high-throughput proteomics approaches using K5.TGFβ1 skin at different disease stages and samples from human inflammatory skin diseases could also provide important molecular biomarkers of TGFβ-mediated inflammation. These experiments will help us delineate differences and similarities in the pathogenesis between TGFβ1 transgenic mice and human inflammatory skin diseases.

Moreover, this mouse model will allow us to test various therapeutic strategies for controlling inflammatory skin diseases. Because the experimental therapeutic approaches explored in K5.TGFβ1 mice cannot completely or permanently reverse TGFβ1-induced skin inflammation, direct inhibition of TGFβ1 in the skin should be explored as a therapeutic strategy for inflammatory skin diseases where TGFβ1 overexpression plays a causal role in disease pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Pamela Garl for proof reading. Original work in the Wang Lab was supported by NIH grants CA80849, AR061792 and DE15953 to XJW and by the Dermatology Foundation fellowship to GH. PW was supported by grants from the Austrian National Bank Jubilee funds no. 11729 and 13279. TPS was supported through the PhD Program Molecular Medicine, subprogram Molecular Inflammation (MOLIN), Medical University of Graz, Austria.

Abbreviations

- TGFβ

transformation growth factor β

- IL

interleukin

- Th

T helper

- AD

atopic dermatitis

- PUVA

8-methoxypsoralen plus ultraviolet A therapy

- ROR

retinoic acid-related orphan receptor

- STAT

signal-transducer and activator of transcription, Foxp, forkhead box p

- Tregs

regulatory T cells

- PAF

platelet-activating factor

- GWAS

genomewide association study.

References

- 1.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–84. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCartney-Francis NL, Wahl SM. Transforming growth factor beta: a matter of life and death. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;55:401–9. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shull MM, Ormsby I, Kier AB, Pawlowski S, Diebold RJ, Yin M. et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359:693–9. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kulkarni AB, Karlsson S. Inflammation and TGF beta 1: lessons from the TGF beta 1 null mouse. [Review] [27 refs] Research in Immunology. 1997;148:453–6. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(97)82669-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borkowski TA, Letterio JJ, Mackall CL, Saitoh A, Farr AG, Wang XJ. et al. Langerhans cells in the TGF beta 1 null mouse. Advances in Experimental Medicine & Biology. 1997;417:307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borkowski TA, Letterio JJ, Mackall CL, Saitoh A, Wang Xj. et al. A role for TGFbeta1 in langerhans cell biology. Further characterization of the epidermal Langerhans cell defect in TGFbeta1 null mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;100:575–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI119567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li AG, Wang D, Feng XH, Wang XJ. Latent TGFbeta1 overexpression in keratinocytes results in a severe psoriasis-like skin disorder. EMBO J. 2004;23:1770–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang XR, Chung A.C, Zhou L, Wang X.J, Lan H.Y. Latent TGF-beta1 protects against crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:233–42. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han G, Williams CA, Salter K, Garl PJ, Li AG, Wang XJ. A Role for TGFbeta Signaling in the Pathogenesis of Psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;130:371–7. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohammed J, Ryscavage A, Perez-Lorenzo R, Gunderson AJ, Blazanin N, Glick AB. TGFbeta1-induced inflammation in premalignant epidermal squamous lesions requires IL-17. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:2295–303. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swindell WR, Johnston A, Carbajal S, Han G, Wohn C, Lu J. et al. Genome-wide expression profiling of five mouse models identifies similarities and differences with human psoriasis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Cesare A, Di Meglio P, Nestle F.O. The IL-23/Th17 axis in the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1339–50. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lew W, Bowcock A.M, Krueger J.G. Psoriasis vulgaris: cutaneous lymphoid tissue supports T-cell activation and "Type 1" inflammatory gene expression. Trends Immunol. 2004. pp. 295–305. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Nestle FO, Di Meglio P, Qin J.Z, Nickoloff B.J. Skin immune sentinels in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009. pp. 679–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Annunziato F, Cosmi L, Liotta F, Maggi E, Romagnani S. Type 17 T helper cells-origins, features and possible roles in rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009. pp. 325–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.de Cid R, Riveira-Munoz E, Zeeuwen P.L. et al. Deletion of the late cornified envelope LCE3B and LCE3C genes as a susceptibility factor for psoriasis. Nat Genetic. 2009;41:211–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006. pp. 235–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O'Quinn DB, Helms WS, Bullard DC, Elson CO. et al. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441:231–4. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–89. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, Yang XP, Tato CM, McGeachy MJ, Konkel JE. et al. Generation of pathogenic T(H)17 cells in the absence of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 2010;467:967–71. doi: 10.1038/nature09447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Garra A, Stockinger B, Veldhoen M. Differentiation of human T(H)-17 cells does require TGF-beta! NatImmunol. 2008;9:588–90. doi: 10.1038/ni0608-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oppmann B, Lesley R, Blom B, Timans JC, Xu Y, Hunte B. et al. Novel p19 protein engages IL-12p40 to form a cytokine, IL-23, with biological activities similar as well as distinct from IL-12. Immunity. 2000;13:715–25. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pirhonen J, Matikainen S, Julkunen I. Regulation of virus-induced IL-12 and IL-23 expression in human macrophages. J Immunol. 2002;169:5673–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piskin G, Sylva-Steenland RM, Bos JD, Teunissen MB. In vitro and in situ expression of IL-23 by keratinocytes in healthy skin and psoriasis lesions: enhanced expression in psoriatic skin. J Immunol. 2006;176:1908–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kastelein RA, Hunter C.A, Cua D.J. Discovery and biology of IL-23 and IL-27: related but functionally distinct regulators of inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:221–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo V.K. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parham C, Chirica M, Timans J, A receptor for the heterodimeric cytokine IL-23 is composed of IL-12Rbeta1 and a novel cytokine receptor subunit, IL-23R. J Immunol. 2002. pp. 5699–708. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Lee E, Trepicchio WL, Oestreicher JL, Pittman D, Wang F, Chamian F. et al. Increased expression of interleukin 23 p19 and p40 in lesional skin of patients with psoriasis vulgaris. J Exp Med. 2004;199:125–30. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson NJ, Boniface K, Chan JR, McKenzie BS, Blumenschein WM, Mattson JD. et al. Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. Nature immunology. 2007;8:950–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nair RP, Duffin K.C, Helms C, Genome-wide scan reveals association of psoriasis with IL-23 and NF-kappaB pathways. Nat Genetic. 2009. pp. 199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Krueger GG, Langley R.G, Leonardi C. et al. A human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody for the treatment of psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:580–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leonardi CL, Kimball A.B, Papp K.A, Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 76-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 1) Lancet. 2008. pp. 1665–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Papp KA, Langley R.G, Lebwohl M, Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 52-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 2) lancet. 2008. pp. 1675–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Gottlieb A, Menter A, Mendelsohn A, Ustekinumab, a human interleukin 12/23 monoclonal antibody, for psoriatic arthritis: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Lancet. 2009. pp. 633–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Griffiths CE, Strober B.E, Comparison of ustekinumab and etanercept for moderate-to-severe psoriasis. N England J Medicine. 2010. pp. 118–28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Tonel G, Conrad C, Laggner U, Di Meglio P, Grys K, McClanahan TK. et al. Cutting edge: A critical functional role for IL-23 in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2010;185:5688–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asadullah K, Sabat R, Friedrich M. et al. Interleukin-10: an important immunoregulatory cytokine with major impact on psoriasis. Current Drug Targets Inflammation Allergy. 2004;3:185–92. doi: 10.2174/1568010043343886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Cesare A, Di Meglio P, Nestle F.O. A role for Th17 cells in the immunopathogenesis of atopic dermatitis? J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2569–71. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kryczek I, Bruce A.T, Gudjonsson J.E, Johnston A. et al. Induction of IL-17+ T cell trafficking and development by IFN-gamma: mechanism and pathological relevance in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2008;181:4733–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lowes MA, Kikuchi T, Fuentes-Duculan J, Psoriasis vulgaris lesions contain discrete populations of Th1 and Th17 T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2008. pp. 1207–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Zaba LC, Cardinale I, Gilleaudeau P. et al. Amelioration of epidermal hyperplasia by TNF inhibition is associated with reduced Th17 responses. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3183–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flisiak I, Chodynicka B, Porebski P, Flisiak R. Association between psoriasis severity and transforming growth factor beta(1) and beta (2) in plasma and scales from psoriatic lesions. Cytokine. 2002;19:121–5. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flisiak I, Porebski P, Flisiak R, Chodynicka B. Plasma transforming growth factor beta1 as a biomarker of psoriasis activity and treatment efficacy. Biomarkers. 2003. pp. 437–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Flisiak I, Zaniewski P, Chodynicka B. Plasma TGF-beta1, TIMP-1, MMP-1 and IL-18 as a combined biomarker of psoriasis activity. Biomarkers. 2008. pp. 549–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Nockowski P, Szepietowski J.C, Ziarkiewicz M, Baran E. Serum concentrations of transforming growth factor beta 1 in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Acta Dermatovenerol. 2004;12:2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sugiyama H, Gyulai R, Toichi E, Garaczi E, Shimada S, Stevens SR. et al. Dysfunctional blood and target tissue CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells in psoriasis: mechanism underlying unrestrained pathogenic effector T cell proliferation. J Immunol. 2005;174:164–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fantini MC, Becker C, Monteleone G, Pallone F, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Cutting edge: TGF-beta induces a regulatory phenotype in CD4+CD25- T cells through Foxp3 induction and down-regulation of Smad7. J Immunol. 2004;172:5149–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Korn T, Mitsdoerffer M, Croxford AL, Awasthi A, Dardalhon VA, Galileos G. et al. IL-6 controls Th17 immunity in vivo by inhibiting the conversion of conventional T cells into Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:18460–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809850105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Volpe E, Servant N, Zollinger R, Bogiatzi SI, Hupe P, Barillot E. et al. A critical function for transforming growth factor-beta, interleukin 23 and proinflammatory cytokines in driving and modulating human T(H)-17 responses. Nature immunology. 2008;9:650–7. doi: 10.1038/ni.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh TP, Schon MP, Wallbrecht K, Michaelis K, Rinner B, Mayer G. et al. 8-methoxypsoralen plus ultraviolet A therapy acts via inhibition of the IL-23/Th17 axis and induction of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells involving CTLA4 signaling in a psoriasis-like skin disorder. J Immunol. 2010;184:7257–67. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh TP, Huettner B, Koefeler H, Mayer G, Bambach I, Wallbrecht K. et al. Platelet-activating factor blockade inhibits the T-helper type 17 cell pathway and suppresses psoriasis-like skin disease in K5.hTGF-beta1 transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:699–708. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bornstein S, White R, Malkoski S, Oka M, Han G, Cleaver T. et al. Smad4 loss in mice causes spontaneous head and neck cancer with increased genomic instability and inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3408–19. doi: 10.1172/JCI38854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fitch EL, Rizzo H.L, Kurtz S.E. et al. Inflammatory skin disease in K5.hTGF-beta1 transgenic mice is not dependent on the IL-23/Th17 inflammatory pathway. J Invest Dermatol. 2009:2443–50. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McLean WHaH. et al. Breach delivery: increased solute uptake points to a defective skin barrier in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:8–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toda M, Leung D.Y, Molet S. et al. Polarized in vivo expression of IL-11 and IL-17 between acute and chronic skin lesions. J Allergy Clinical Immunology. 2003;111:875–81. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koga C, Kabashima K, Shiraishi N. et al. Possible pathogenic role of Th17 cells for atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2625–30. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilsmann-Theis D, Hagemann T, Jordan J. et al. Facing psoriasis and atopic dermatitis: are there more similarities or more differences? Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:172–80. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2008.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Madan VaG. et al. Systemic ciclosporin and tacrolimus in dermatology. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:239–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Benedetto A, Agnihothri R, McGirt L.Y, Atopic dermatitis: a disease caused by innate immune defects? J Invest Dermatol. 2009. pp. 14–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Kawakami T. et al. Mast cells in atopic dermatitis. Current Opinions in Immunology. 2009;21:666–78. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grewe M. et al. Analysis of the cytokine pattern expressed in situ in inhalant allergen patch test reactions of atopic dermatitis patients. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:407–10. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12321078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grewe M. et al. A role for Th1 and Th2 cells in the immunopathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Immunology Today. 1998;19:359–61. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jain S. et al. T helper 1 to T helper 2 shift in cytokine expression: an autoregulatory process in superantigen-associated psoriasis progression? J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:180–4. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.003939-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Santamaria AB. et al. p53 and Fas ligand are required for psoralen and UVA-induced apoptosis in mouse epidermal cells. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:549–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]