Abstract

Introduction

The anti-atherogenic and hypotriglyceridemic properties of fish oil are attributed to its enrichment in eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; 20:5, n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; 22:6, n-3). Echium oil contains stearidonic acid (SDA; 18:4, n-3), which is metabolized to EPA in humans and mice, resulting in decreased plasma triglycerides.

Objective

We used apoB100 only, LDLrKO mice to investigate whether echium oil reduces atherosclerosis.

Methods

Mice were fed palm, echium, or fish oil-containing diets for 16 weeks and plasma lipids, lipoproteins, and atherosclerosis were measured.

Results

Compared to palm oil, echium oil feeding resulted in significantly less plasma triglyceride and cholesterol levels, and atherosclerosis, comparable to that of fish oil.

Conclusion

This is the first report that echium oil is anti-atherogenic, suggesting that it may be a botanical alternative to fish oil for atheroprotection.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, fish oil, palm oil, polyunsaturated fatty acids, omega-3 fatty acids, n-3 fatty acids

1. Introduction

Dietary intervention is often the initial approach to reduce risk factors that contribute to cardiovascular heart disease, which is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Westernized societies (1). Dietary consumption of long-chain n-3 PUFAs, such as those found in fatty fish or fish oil (FO) supplements, reduce inflammation, endothelial activation, and platelet activation, resulting in decreased cardiovascular disease (2). The atheroprotective component of FO is attributed to two long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; 20:5 n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; 22:6 n-3). Nonetheless, fatty fish and FO consumption in the United States remains low (2, 3). The North American diet is rich in fatty acids that are pro-inflammatory and pro-atherogenic; 90% of the n-3 PUFAs consumed are in the form of alpha linolenic acid (ALA; 18:3 n-3) (3). However, ALA is not atheroprotective because it requires Δ6-desaturase for conversion to EPA and DHA and this conversion is very inefficiency (~4-16%) in humans and rodents (4, 5). Therefore, an alternative strategy is needed to compensate for the lack of EPA and DHA in the diet.

One approach is to enrich the diet with a fatty acid-containing oil that can be converted to EPA in vivo. Echium oil (EO), derived from the seeds of Echium plantagineum, contains 12-14% of total fatty acids as stearidonic acid (SDA; 18:4 n-3), the immediate product of ALA Δ6-desaturation. We have previously shown that SDA in EO is converted to EPA in plasma and liver lipids of a mouse model of atherosclerosis and hypertriglyceridemia, the apoB100 only LDL receptor knockout (B100 only, LDLrKO) mouse. EO, relative to a palm oil (PO) control diet, also reduced total plasma cholesterol (TPC) and triglyceride (TG) concentrations in B100 only, LDLrKO mice (6). Similar enrichment of lipid fractions with EPA and reductions in plasma TG concentrations were observed in human subjects supplemented with EO (7). These results established EO as a viable botanical alternative to FO for reducing plasma TG concentrations. However, whether EO is also atheroprotective is unknown.

The purpose of the present study was to determine whether EO consumption confers atheroprotection, and, if so, to what extent compared to that of FO. B100 only, LDLrKO mice were used for this study because they are a well-established mouse model for determining the effect of dietary fat saturation on atherosclerosis (8).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and diets

Male apoB100-only LDLrKO mice in the C57BL/6 background (>99%) were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility at Wake Forest School of Medicine in accordance with all institutional animal care and use guidelines. After weaning, the mice were fed a chow diet until 8 weeks of age, at which time they were randomly assigned to one of three diet groups designated as PO, EO, or FO. Each diet contained 0.2% cholesterol and 10% of calories from PO with an additional 10% of calories from PO, EO, or FO, totaling 20% calories as fat. The EO diet contained 1.3% energy as SDA, whereas the FO diet contained 2.5% energy as EPA + DHA. Detailed description of the oils appears in the supplemental methods; diet compositions and fatty acid compositions have been described previously (6, 8). Mice consumed the atherogenic diets for 16 weeks.

2.2 Lipid and lipoprotein analysis

Blood samples were collected from tail veins after a 4h fast. Plasma cholesterol (Wako) and TG (Roche) were determined by enzymatic analysis according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Fresh plasma from the terminal bleed at 16 weeks was used to determine lipoprotein cholesterol distribution after FPLC fractionation of plasma (6). Fatty acid composition of plasma was determined as previously described (6).

2.3 Atherosclerosis quantification

Mice were terminated after 16 weeks of diet feeding and aortas were isolated, cleaned of adventitia, and mounted en face for measurement of surface lesion area using WCIF Image J software. Aortic total and free cholesterol concentrations were quantified by gas liquid chromatography and normalized to aortic protein content (8). Cholesteryl ester (CE) was calculated as: TC-FC X 1.67 (to correct for fatty acid loss). Hearts were frozen in Optimal Cutting Temperature compound, sectioned (8μm), stained with Oil Red O, and intimal area was measured using Image Pro plus software (9).

2.4 Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Differences among the 3 diet groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA (p<0.05) using GraphPad Prism software. For plasma TG and TPC, the area under the curve (AUC) was determined for individual animals and differences among the groups were determined by one-way ANOVA (p<0.05). Individual diet group differences were identified using Tukey’s post-test analysis.

3. Results

3.1 Echium oil feeding results in decreased plasma lipids and apoB lipoproteins

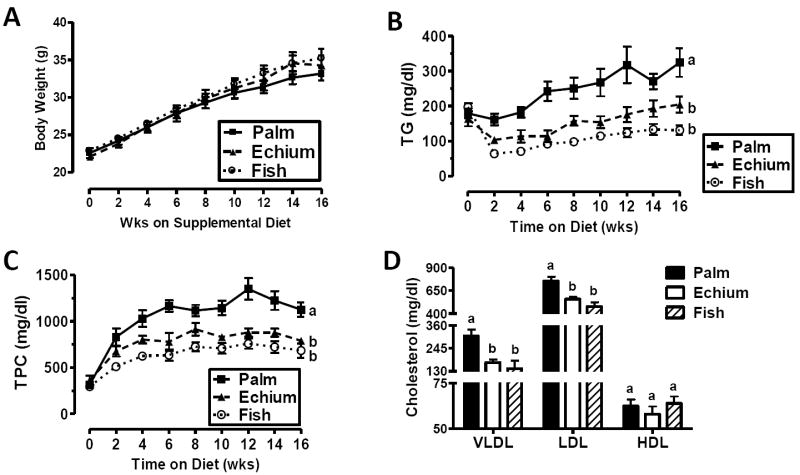

In our previous study, experimental diet feeding was limited to 8 weeks (6) and atherosclerosis was not evaluated. Here, we extended the feeding period to 16 weeks to investigate atherosclerosis development. Mice in all three diet groups gained body weight at similar rates (Figure 1A). Plasma fatty acid compositions were similar to those reported previously (6), with mice fed EO exhibiting an enrichment in EPA, but not DHA, relative to those fed PO (Supplemental figure 1). Mice fed the EO diet had a rapid, significant, and sustained reduction in plasma TG levels compared to PO fed controls (Figure 1B), which was similar to that of FO-fed mice. EO also resulted in significantly lower TPC concentrations during the study compared with mice fed PO (Figure 1C), similar to that of mice fed FO. This reduction was due to significant reductions in VLDL and LDL cholesterol compared with PO-fed mice (Figure 1D); HDL concentrations were similar among the three diet groups.

Figure 1. The effect of atherogenic diets on body weight and plasma lipid and lipoprotein concentrations.

Eight week old B100-only LDLrKO mice were fed diets for 16 weeks consisting of 0.2% cholesterol and 10% of calories from PO, with an additional 10% from PO, EO, FO (n=11-16 mice per group). Periodically, body weights (A) were determined and blood was obtained to assay plasma TG (B) and TPC (C) by enzymatic assays. (D) At 16 weeks, a terminal blood sample was used to fractionate plasma by FPLC and measure plasma lipoprotein cholesterol distribution. Values are mean ±S.E.M. Results with different letters denote significant differences among diet groups (P<.05).

3.2 Echium oil reduces atherosclerosis in apoB100-LDLrKO mice

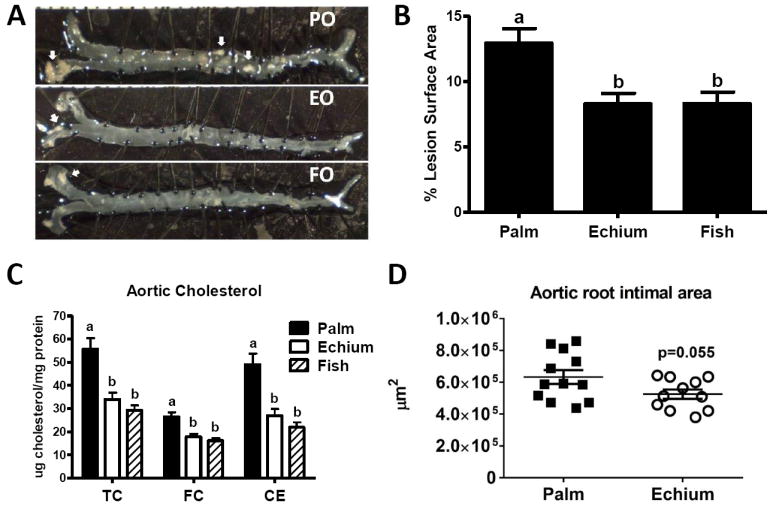

Representative aortic images of mice from each diet group illustrate the predominant aortic arch localization of raised lesions (Figure 2A). Aortic lesion surface area was significantly reduced in EO and FO fed mice compared to the PO fed group (Figure 2B). Aortic cholesterol (TC, FC and CE) concentrations were significantly lower for EO and FO groups vs. the PO group (Figure 2C), but similar for EO and FO fed mice (Figure 2B and 2C). There was also a strong correlation between aortic CE content and percent surface lesion area (r2=0.6783; data not shown). Finally, aortic root intimal area was reduced 17% in EO vs. PO fed mice (p=0.055) (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Echium oil reduces atherosclerosis.

Mice were sacrificed and aortas were removed for atherosclerosis quantification (n=12-16 mice per group). (A) Representative aorta from each diet group with atherosclerotic lesions identified by white arrows. (B) Quantification of aortic surface lesion area. (C) Aortic total cholesterol (TC), free cholesterol (FC) and cholesteryl ester (CE), measured by gas-liquid chromatography. Values are mean ± S.E.M. Bars with different letters denote significant differences among diet groups (P<0.05). (D) Aortic root intimal area. Frozen sections (8 μm) of the aortic root were stained with Oil Red O and intimal area was quantified using Image Pro software in three sections from each mouse. Each point denotes the average intimal area (n=3 sections) per mouse, whereas the horizontal lines indicate the group mean ± SEM.

4. Discussion

Due to the high incidence of cardiovascular disease and the low consumption of FO and/or fatty fish in the United States (2), the goal of our study was to determine whether EO could serve as a botanical source of n-3 PUFAs for atheroprotection. Using a mouse model of atherosclerosis, we show for the first time that EO feeding results in decreased atherosclerosis compared to mice fed PO and is equivalent in atheroprotection to FO.

Multiple health benefits of n-3 PUFAs have been demonstrated in animal and human studies (10). However, fish is not commonly consumed in the US population (3). In addition, FO supplements are not widely accepted due to gastrointestinal intolerance and fishy aftertaste (2, 11). As such, ALA in vegetable oils supplies most of the n-3 PUFAs in the Western diet (3). Although n-3 PUFAs, in general, are less inflammatory than n-6 PUFAs, only long-chain (>18 carbon) PUFAs, such as EPA and DHA, confer atheroprotection (10, 11). The enzyme Δ-6 desaturase is the rate limiting step in ALA conversion to EPA and DHA. EO offers a natural source of stearidonic acid (SDA), the immediate product of ALA Δ-6 desaturation and, therefore, serves as a suitable source for EPA enrichment (7). In human studies and our experiments using B100 LDLrKO mice, EO consumption was associated with significant reductions in plasma TG concentrations (6, 7), which is the most consistent observation with FO feeding. Furthermore, plasma TG concentrations may be an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (12). EO feeding likely reduced atherosclerosis in our study by reducing plasma LDL and VLDL concentrations (Figure 2D). Presumably, EO also reduces atherosclerosis by additional mechanisms (i.e., limiting inflammation) similar to those reported for FO (13), but this remains to be determined in future studies.

In conclusion, we found that dietary EO reduced aortic atherosclerosis in B100-LDLrKO mice. Based on our findings in mice and the hypotriglyceridemic effects of EO supplementation in humans, we propose that EO may be a suitable botanical alternative to FO to reduce plasma TG levels and confer atheroprotection. Thus, in instances in which dietary consumption of EPA and DHA is low, e.g. in the United States and Westernized countries, the health benefits of EO should outweigh those of botanical oils enriched in ALA. This may be particularly true with regard to hypertriglyceridemia and cardiovascular disease. However, because EO does not result in DHA enrichment equivalent to FO, due to limited Δ-6 desaturase-mediated conversion of EPA to DHA, EO is not a complete substitute for FO and may not satisfy the body’s essential need for DHA for brain and retinal development (7).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grant numbers P50AT002782, R01HL094525, and P01HL049373 to JSP. Croda Chemicals provided the echium oil used in our diets and Omega Protein Inc. provided the OmegaPure refined menhaden oil for our FO diet. We gratefully acknowledge Karen Klein (Research Support Core, Wake Forest School of Medicine) for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ. Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2002;106:2747–2757. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000038493.65177.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kris-Etherton PM, Taylor DS, Yu-Poth S, Huth P, Moriarty K, Fishell V, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids in the food chain in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:179S–188S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.1.179S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang YS, Smith RS, Redden PR, Cantrill RC, Horrobin DF. Modification of liver fatty acid metabolism in mice by n-3 and n-6 delta 6-desaturase substrates and products. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1082:319–327. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(91)90208-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singer P, Berger I, Wirth M, Godicke W, Jaeger W, Voigt S. Slow desaturation and elongation of linoleic and alpha-linolenic acids as a rationale of eicosapentaenoic acid-rich diet to lower blood pressure and serum lipids in normal, hypertensive and hyperlipemic subjects. Prostaglandins Leukot Med. 1986;24:173–193. doi: 10.1016/0262-1746(86)90125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang P, Boudyguina E, Wilson MD, Gebre AK, Parks JS. Echium oil reduces plasma lipids and hepatic lipogenic gene expression in apoB100-only LDL receptor knockout mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19:655–663. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Surette ME, Edens M, Chilton FH, Tramposch KM. Dietary echium oil increases plasma and neutrophil long-chain (n-3) fatty acids and lowers serum triacylglycerols in hypertriglyceridemic humans. J Nutr. 2004;134:1406–1411. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.6.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudel LL, Kelley K, Sawyer JK, Shah R, Wilson MD. Dietary monounsaturated fatty acids promote aortic atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-null, human ApoB100-overexpressing transgenic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:1818–1827. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.11.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daugherty A, Whitman SC. Quantification of atherosclerosis in mice. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;209:293–309. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-340-2:293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calder PC, Grimble RF. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation and immunity. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56(Suppl 3):S14–S19. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Mehra MR, Ventura HO. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Diseases. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;54:585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hokanson JE, Austin MA. Plasma triglyceride level is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease independent of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level: a meta-analysis of population-based prospective studies. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1996;3:213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yaqoob P, Calder PC. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammation in the arterial wall. Eur J Med Res. 2003;8:337–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.