Abstract

The intrinsic activity of coagulation factor VIIa (FVIIa) is dependent on Ca2+ binding to a loop (residues 210–220) in the protease domain. Structural analysis revealed that Ca2+ may enhance the activity by attenuating electrostatic repulsion of Glu296 and/or by facilitating interactions between the loop and Lys161 in the N-terminal tail. In support of the first mechanism, the mutations E296V and D212N resulted in similar, about 2-fold, enhancements of the amidolytic activity. Moreover, mutation of the Lys161-interactive residue Asp217 or Asp219 to Ala reduced the amidolytic activity by 40–50%, whereas the K161A mutation resulted in 80% reduction. Hence one of these Asp residues in the Ca2+-binding loop appears to suffice for some residual interaction with Lys161, whereas the more severe effect upon replacement of Lys161 is due to abrogation of the interaction with the N-terminal tail. However, Ca2+ attenuation of the repulsion between Asp212 and Glu296 keeps the activity above that of apoFVIIa. Altogether, our data suggest that repulsion involving Asp212 in the Ca2+-binding loop suppresses FVIIa activity and that optimal activity requires a favorable interaction between the Ca2+-binding loop and the N-terminal tail. Crystal structures of tissue factor-bound FVIIaD212N and FVIIaV158D/E296V/M298Q revealed altered hydrogen bond networks, resembling those in factor Xa and thrombin, after introduction of the D212N and E296V mutations plausibly responsible for tethering the N-terminal tail to the activation domain. The charge repulsion between the Ca2+-binding loop and the activation domain appeared to be either relieved by charge removal and new hydrogen bonds (D212N) or abolished (E296V). We propose that Ca2+ stimulates the intrinsic FVIIa activity by a combination of charge neutralization and loop stabilization.

The proteolytically activated form of blood coagulation factor VII (FVII),2 FVIIa, behaves zymogen-like with low enzymatic activity as opposed to other, constitutively active serine proteases of the coagulation cascade. Only upon full activation of FVIIa by tissue factor (TF) binding is the cascade initiated by activation of coagulation factors IX and X, in turn leading to the generation of thrombin (1–3). Thrombin then cleaves fibrinogen to fibrin that polymerizes to give a clot that permanently cessates the bleeding (4, 5).

As for all trypsin-like serine proteases, the activation of enzymes in the coagulation cascade involves tethering of the N terminus, created after proteolytic cleavage of the zymogen forms, to the activation domain within the protease domain with concomitant stabilization of its three activation loops (6–8). In the active conformation of FVIIa, a salt bridge is formed between the N-terminal α-amino group of Ile153 and the side chain of Asp343 in the activation pocket of the activation domain.3 The latter is positioned next to the active site Ser344 (9). FVIIa is only fully active upon TF binding and Ca2+ binding to nine sites located in three different domains, including the Ca2+-binding Glu210–Glu220 loop in the protease domain (10, 11). Upon binding of the cofactors, an activity increase of several 1,000-fold is observed, in part by shifting the equilibrium from the zymogen-like form toward the catalytically active conformation of FVIIa (12, 13). Ca2+ binding alone leads to a more than 10-fold increase in activity (14).

Interestingly, the activating effect of TF has been partially mimicked by means of grafting (see Ref. 15) and site-directed mutagenesis (see Ref. 16) of the loop succeeding the TF-interactive helix (residues 306–312) yielding FVIIa variants with increased intrinsic activity. Replacements of residues in the vicinity of the activation domain have also improved FVIIa activity. Notably, the residues Val158, Glu296, and Met298 appear to form a zymogenicity-determining triad close to the activation domain. Replacements by the corresponding three residues in homologous coagulation factors have resulted in FVIIa variants with substantially increased intrinsic activity (17–19). The most dramatic increase requires conversion of the entire 3-residue motif to that found in thrombin and factor IXa (V158D/E296V/M298Q-FVIIa) (FVIIaDVQ) (17). Mutation of Glu296 to Val reduced the dependence on Ca2+ suggesting a link to the stimulatory Ca2+ effect, possibly via insertion of the N terminus (20). Moreover, residue 296 has been linked to macromolecular substrate-induced maturation of the catalytic cleft as inferred from a conformational change upon binding of a monoclonal antibody (21, 22).

Using a change-of-function mutagenesis and crystal structural approach, we have further investigated the zymogenicity and Ca2+ dependence of FVIIa. We hypothesized that the effects of Ca2+ on FVIIa activity are through stabilization of the Ca2+-binding loop, i.e. stabilization of the interaction(s) of Asp217/Asp219 with Lys161 in the N-terminal tail, and through alleviation of charge repulsion between the loop, primarily Asp212, and the nearby Glu296. The latter residue had been mutated in an earlier study (20) and the other four were replaced in the present study to obtain a complete set of variants to test the hypothesis. Lys161, Asp217, and Asp219 were replaced by Ala to remove the charges without introducing new interactions (van der Waals or hydrogen bonds). Asp212 was replaced by Asn hereby removing the charge with minimal alteration.

Our data suggest that Ca2+ binding to the 210–220 loop in the protease domain of FVIIa promotes the intrinsic activity through stabilization of electrostatic interactions of Asp217 and Asp219 with Lys161 in the N-terminal tail and mitigation of the repulsion by Asp212 of Glu296 located close to loop 1 of the activation domain. Indeed, Asp212 was identified as a new zymogenicity determinant, because the charge removal led to an increased intrinsic activity and degree of N terminus burial.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein Preparations—The construct pLN174 consisting of the cDNA encoding wild-type human FVII inserted into pZem219b was previously described (23). The mutations were introduced into pLN174 using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and the following primers (only sense primers given), with base substitutions in italics and the affected codons underlined, were used to introduce the indicated mutations: K161A, 5′-G GGG GGC AAG GTG TGC CCC GCA GGG GAG TGT CCA TGG CAG GTC C; D212N, 5′-C CTG ATC GCG GTG CTG GGC GAG CAC AAC CTC AGC GAG CAC G; D217A, 5′ C CTC AGC GAG CAC GCC GGG GAT GAG C; D219A, 5′ G CAC GAC GGG GCT GAG CAG AGC C.

Baby hamster kidney and Chinese hamster ovary-K1 cell lines producing the FVIIa mutants were generated as described (24). The baby hamster kidney cell line producing the V158D/E296V/M298Q mutant was previously described (17). Purification of wild-type and mutant FVII from cell culture medium was carried out essentially as described (17, 25) using an anion-exchange and immunoaffinity based purification process. Activation of zymogen FVII was performed either by autoactivation or by the use of Sepharose-coupled FXa or soluble FIXa. The latter was separated from FVIIa using an immunoaffinity column. FVIIa concentrations were estimated from absorbance measurements at 280 nm. Active FVIIa enzyme concentrations were determined by an amidolytic activity assay; the activities of the FVIIa variants, diluted to 10 nm and mixed with 50 nm sTF, were compared with those of mixtures of 10 nm sTF and 50 nm FVIIa variant (from which the activity of excess FVIIa variant had been subtracted). If the activities of the two mixtures were indistinguishable, the originally estimated concentration of FVIIa variant equaled the active concentration and if not, the active concentration was adjusted ([active FVIIa] = estimated [FVIIa] multiplied by the activity ratio (10 nm FVIIa plus 50 nm sTF/10 nm sTF plus 50 nm FVIIa)). This method allows for the calculation of relative activities (Table 1). Plasma-derived FX and FXa were from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN). Active site-inhibited FVIIa variants were obtained by incubation with the inhibitor PhePheArg-chloromethylketone essentially as described (26). Soluble TF (sTF, residues 1–209) was produced as described (27). Antithrombin (AT) was from Hematologic Technologies (Essex Junction, VT).

TABLE 1.

Functional and conformational characterization

| Relative amidolytic activity | Relative proteolytic activity | Relative carbamylation rate | Relative antithrombin inhibition rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| FVIIaD212N | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.04 |

| FVIIaDVQ | 6.2 ± 0.6 | 25 ± 3.4a | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.6 |

| FVIIaK161A | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | NDb | ND |

| FVIIaD217A | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | ND | ND |

| FVIIaD219A | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | ND | ND |

Value from Ref. 20.

ND, not determined.

Amidolytic and Proteolytic Activity Assays—All measurements were performed at room temperature in 50 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, containing 0.1 m NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2, and 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin. The amidolytic activity of variant/wild-type FVIIa (100 nm) was measured with or without 1 μm sTF. Initial kinetic rates were determined from absorbance (405 nm) development using the chromogenic substrate S-2288 (2.5 mm) (H-d-Ile-Pro-Arg-p-nitroanilide, Chromogenix) monitored for 5–30 min with readings every 30 s in a SpectraMax 340 microplate reader (Global Medical Instrumentation, Inc., MN). The proteolytic activities were measured by incubating 50 nm FVIIa variant with 1 μm FX for 40 min, stopping the reaction with excess EDTA, and measuring the resulting FXa activity by adding 0.5 mm S-2765 (Z-d-Arg-Gly-Arg-p-nitroanilide, Chromogenix). The rate of substrate hydrolysis catalyzed by a FVIIa mutant was divided by the rate seen with wild-type FVIIa to obtain the relative activity.

Carbamylation Assay—The carbamylation of Ile153 was performed by incubation of 100 nm to 2 μm variant/wild-type FVIIa with 0.2 m potassium cyanate in assay buffer (see above) without bovine serum albumin. Samples were withdrawn at different time points and diluted 10-fold in assay buffer containing 5 mm S-2288 and hydrolysis was monitored for 2–5 min as described for the amidolytic assay.

AT Inhibition Assay—AT inhibition was performed by incubation of 100 nm variant/wild-type FVIIa with 100 μg/ml AT and 1 unit/ml heparin in assay buffer. Samples were withdrawn at different time points and diluted 2-fold in assay buffer containing 5 mm S-2288 and hydrolysis monitored for 2–5 min.

Crystallization Conditions—Active site-inhibited FVIIa mutants in complex with sTF-(1–209) were purified using a Superdex75 16/60 prep-grade column (Amersham Biosciences). A buffer composition of 10 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, and 15 mm CaCl2 was used. Crystals were obtained using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method using 0.1 m sodium citrate, pH 5.6, 16% (w/v) PEG4000, 12% (v/v) 1-propanol, and a protein concentration of 3–4 mg/ml (28). The crystals grew as thin plates with dimensions up to 0.4 × 0.6 × 0.05 mm.

Crystal Data Collection and Processing—Crystallographic data collection was performed at the synchrotron beam lines MaxLab 711/911 (MaxLab, Lund, Sweden) (29). Crystals were flash frozen in a cryoprotective solution composed of precipitating solution with 20% (v/v) glycerol. Data reduction calculations were performed with the XDS software package (30). The structures were solved by the molecular replacement method using the Molrep program, part of the CCP4 package (31, 32), and PDB code 1DAN as a search model (9). Model building was performed using the Coot program (33) and maximum likelihood based iterative refinement, initially performed as a rigid body refinement, using the Refmac5 program, part of the CCP4 package (32, 34). The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (35) was used for structure analysis and creation of figures.

RESULTS

Functional Characterization—The intrinsic amidolytic activities were measured for FVIIaD212N, FVIIaDVQ, and Ala mutants at positions Lys161, Asp217, and Asp219 using the peptidyl substrate S-2288 (Table 1). It is worth mentioning that none of the removed Asp residues (212, 217, and 219) are side chain Ca2+ ligands (9). The amidolytic activity of free FVIIaD212N was increased 2-fold compared with wild-type FVIIa, whereas that of FVIIaDVQ was considerably higher as previously reported (17, 20). The three Ala mutants exhibited reduced amidolytic activities. In the presence of sTF-(1–209), no significant difference in activity between FVIIaD212N, FVIIaDVQ, and wild-type FVIIa could be observed, indicating that the activity-enhancing effects of the mutations are manifested only in the absence of the cofactor. In contrast, FVIIaK161A, FVIIaD217A, and FVIIaD219A displayed a similar reduction in amidolytic activity whether bound to sTF or not.

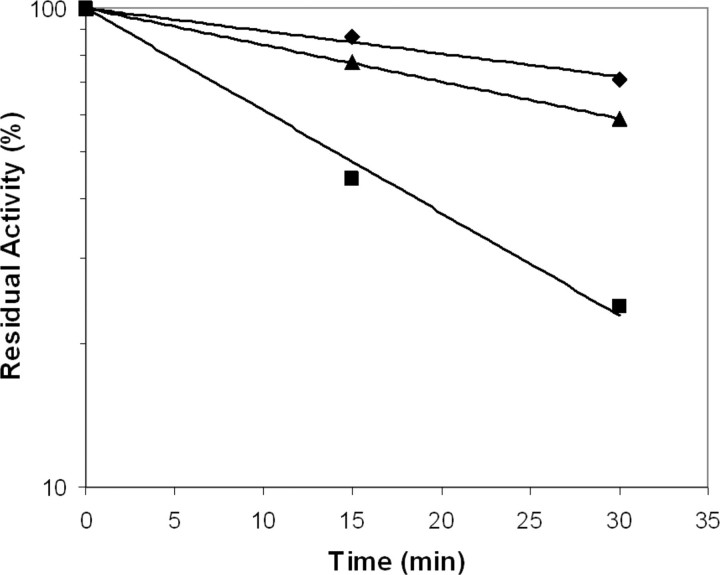

To further characterize the variants with increased intrinsic activity, we performed inhibition experiments using the serpin AT in the presence of heparin. Previous studies have demonstrated that TF enhances the susceptibility to inhibition by AT/heparin 33-fold compared with the free form of FVIIa as a result of TF-induced maturation of the active site (36, 37). Similarly, increased AT inhibition rates of FVIIa variants with increased intrinsic activities have also been shown to correlate with the levels of intrinsic amidolytic activity (17, 20). In line with this, FVIIaD212N and FVIIaDVQ displayed ∼2- and 5-fold faster inhibition compared with wild-type reflecting their relative activities (Fig. 1 and Table 1). This supports the notion that the amino acid changes in the Ca2+-binding loop and those close to the activation domain surrounding the N terminus affect the degree of maturation of the active site. With sTF-(1–209), the AT inhibition of FVIIaD212N and FVIIaDVQ was indistinguishable from that of wild-type FVIIa (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Antithrombin inhibition assay. At the indicated time points, aliquots of wild-type FVIIa (♦), FVIIaD212N (▴), and FVIIaDVQ (▪) were withdrawn and the residual activity measured. The curves show the result of a representative experiment. Similar results were obtained in two additional experiments in which samples where withdrawn at time points different from the experiment presented (data not shown).

The proteolytic activity of free FVIIaD212N was significantly decreased compared with wild-type FVIIa (Table 1). We perceive this as an apparent Km effect, because FVIIaD212A in the presence of sTF has previously been reported to have an equally decreased proteolytic activity (38). The three Ala mutants exhibited reductions of proteolytic activity in parallel with the amidolytic activities.

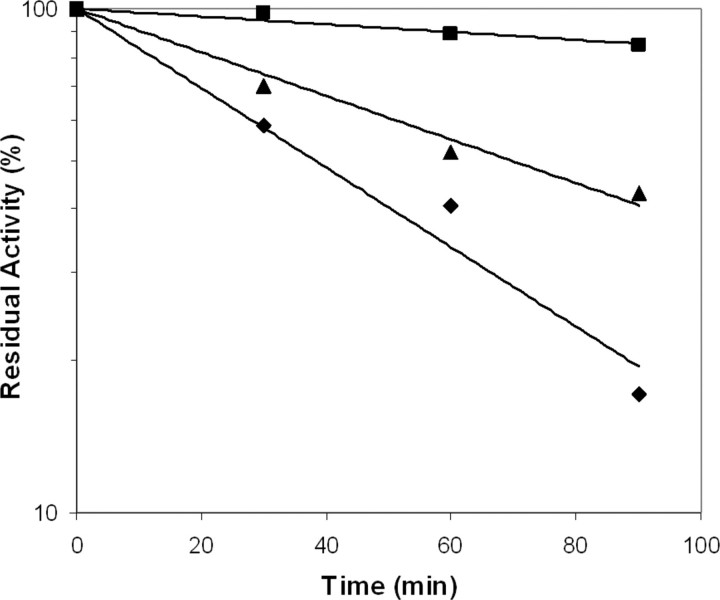

It has been shown that the activating effect of TF on FVIIa is directly linked to insertion of the N terminus into the activation pocket (39). Chemical modification of the exposed α-amino group of the NH-terminal Ile153 of FVIIa prevents formation of the salt bridge with Asp343. We used carbamylation to assess the extent of burial of the N terminus in the activation pocket and found that FVIIaD212N and FVIIaDVQ were modified about 2- and 10-fold slower than wild-type FVIIa, respectively, indicating a more stably buried N terminus in both variants (Fig. 2 and Table 1). This suggests that the conformational equilibria of FVIIaD212N and FVIIaDVQ are shifted toward the catalytically active conformation compared with that of wild-type FVIIa.

FIGURE 2.

Carbamylation inhibition assay using KOCN. At the indicated time points, aliquots of wild-type FVIIa (♦), FVIIaD212N (▴), and FVIIaDVQ (▪) were withdrawn and the residual activity measured. The curves show the result of a representative experiment. Similar results were obtained in two additional experiments in which samples were withdrawn at time points different from the experiment presented (data not shown).

We have previously shown that Ca2+ has a reduced influence on the amidolytic activity of FVIIaDVQ due to the E296V mutation (20). Removal of Ca2+ resulted in the loss of ∼30% of the activity of FVIIaDVQ, whereas the amidolytic activities of all the other mutants, including FVIIaD212N, and FVIIa were reduced by more than 90%. To pinpoint the reason for the stimulatory effect of Ca2+ on FVIIa activity, we studied the importance of the interactions between Asp217 and Asp219 in the Ca2+-binding loop and Lys161 in the N-terminal tail. Replacing either Asp217 or Asp219 by Ala reduced the amidolytic activity by 40–50% in the presence of Ca2+ (Table 1). The substitution of Lys161 for Ala reduced the activity even further (about 20% residual activity). The reduced activity of the Ala mutants precluded differentiation from wild-type FVIIa in terms of AT inhibition and carbamylation, which occurs very slowly and rapidly, respectively, already in FVIIa. The intermediate activities of the two Asp to Ala mutants indicate that one Asp residue suffices for some residual interaction with Lys161, whereas the more severe effect upon substitution of Ala for Lys161 is due to abrogation of the interaction of the Asp residues in the Ca2+-binding loop with the N-terminal tail. However, the activity of FVIIaK161A in the presence of Ca2+ was still higher than that of FVIIa in the absence of Ca2+ probably because the repulsion between Asp212 and Glu296 becomes attenuated by Ca2+.

Structure Determinations of FVIIaD212N and FVIIaDVQ in Complex with sTF-(1–209)—The structures of active site-inhibited FVIIaD212N and FVIIaDVQ in complex with sTF-(1–209) were determined to 2.70- and 2.20-Å resolution, respectively (Table 2). In the case of FVIIaDVQ, the cell parameters indicated higher symmetry space groups, but scaling of intensities in the XDS program package showed the actual symmetries to be monoclinic. Due to high diffraction anisotropy, the FVIIaDVQ structure displayed an overall completeness of 80.3%. This was primarily due to low completeness of the outermost resolution bins, despite acceptable I/σ-values (>2.0) in these bins. Completeness for data below 2.4 Å was, however, above 96%.

TABLE 2.

Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics

| sTF1-209-FVIIaDVQ | sTF1-209-FVIIaD212N | |

|---|---|---|

| Space group | P1211 (sg 4) | P1211 (sg 4) |

| Unit cell (Å/o) | ||

| a/α | 78.36/90.00 | 78.41/90.00 |

| b/β | 68.56/90.22 | 68.79/98.28 |

| c/γ | 78.82/90.00 | 148.58/90.00 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.08 | 1.05 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 29.19-2.20 | 19.90-2.70 |

| No. of measured reflections | 63,917 | 140,643 |

| No. of unique reflections | 34,719 | 42,930 |

| Redundancy | 1.8 | 3.3 |

| Completeness (%) | 80.3 (26.0) | 98.9 (97.9) |

| I/σ(I) | 6.9 (2.1) | 6.9 (2.5) |

| Rmergea (%) | 9.6 (22.9) | 14.8 (52.6) |

| R/Rfreeb | 23.3/29.4 | 27.7/33.8 |

| Number of molecules per asymmetric unit | 1 | 2 |

| Number of atoms | ||

| Non-hydrogen atoms | 4456 | 8289 |

| Water molecules | 280 | 53 |

| Average B-factor (all atoms, Å2) | 33.1 | 27.1 |

| Root mean square bond lengths (Å) | 0.019 | 0.029 |

Rmerge = ∑hkl| — 〈Ihkl〉|/∑hklIhkl, where Ihkl and 〈Ihkl〉 are the diffraction intensity value of the individual measurement and the corresponding mean value for reflection hkl, respectively.

R = ∑hkl||Fobs| — |Fcal||/∑|Fobs|, where Fobs and Fcal are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes for reflection hkl. Rfree is a cross-validation set of 5% omitted reflections from refinement.

The structures were solved by means of the molecular replacement method using amino acid coordinates of the previously published PhePheArg-cmk inhibited FVIIa-TF structure (PDB code 1DAN) as a search model (9). One outstanding solution in the molecular replacement search was obtained for each of the scaled datasets of FVIIaDVQ and FVIIaD212N with one and two molecules, respectively, per asymmetric unit. Refinements were initially performed using rigid body minimization and followed by several cycles of restrained refinement. In the case of FVIIaD212N, non-crystallographic symmetry-restrained refinement was used with medium restraints for both main chain and side chain atoms.

The protein models were inserted into the electron densities and further model building of the covalently bound inhibitor PhePheArg-cmk was performed followed by addition of water molecules. The mutated residues were identified in the electron density. Because of poor or lacking density, a large N-terminal portion (Ala1–Gly47 in both FVIIaD212N and FVIIaDVQ) of the light chain and several loops of the second fibronectin-like domain of TF (different in the FVIIaD212N- and FVIIaDVQ-sTF structures) were excluded in the final structure models. Altogether, 1073 of 1230 and 539 of 615 residues in total were defined in a 2Fo – Fc electron density map at 1σ cut-off of FVIIaD212N/sTF-(1–209) (crystallographic dimer) and FVIIaDVQ/sTF-(1–209), respectively. High flexibility in these parts is assumed to be the reason for absent or poorly defined electron density. All mutations were located in the well defined protease domain, distant from the poorly defined parts, and did not appear to influence the overall fold of the protease domain as such. The protease domains of both variants displayed an excellent trace, which was also reflected in the lowest overall domain flexibility as judged from temperature factors.

The overall conformations of sTF-(1–209) and the FVIIa variants and the arrangements of the light and heavy chains of the FVIIa variants were very similar to the published structure of Banner and colleagues (PDB code 1DAN) (9). However, distinct differences could be observed between the two FVIIa variants in the environment of the mutated residues in the protease domain.

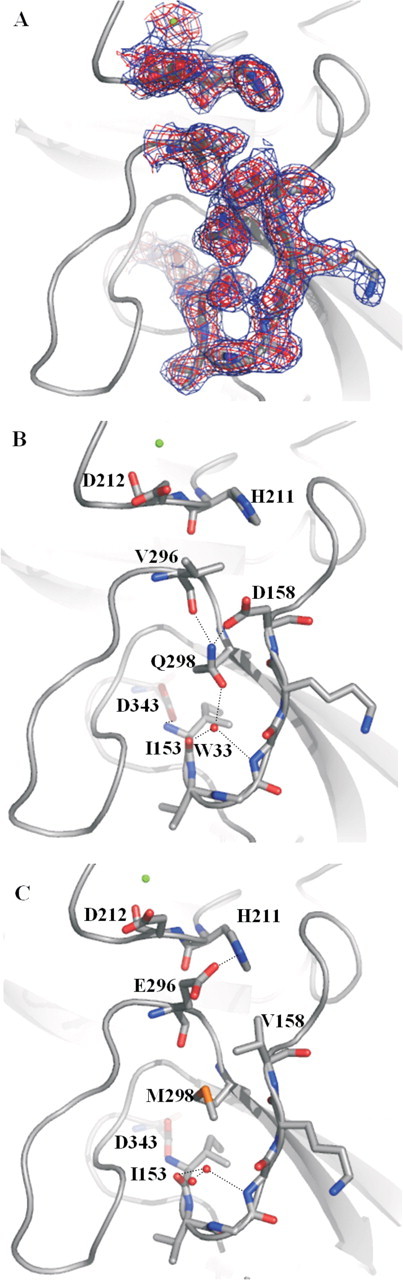

In the structure of FVIIaDVQ-sTF-(1–209), the three mutated residues, Asp158, Val296, and Gln298, are clearly defined in the electron density at a cutoff of 2σ (Fig. 3A). A new hydrogen bond network is established by the introduction of the side chains Asp158 and Gln298, involving the backbone carbonyls of Ile153, Gly156, Val296, and a water molecule (designated W33). This is in good agreement with a previously published model (17). This hydrogen bond network appears to exert a stabilizing effect on the N terminus in accordance with the decreased carbamylation rate of the α-amino group of Ile153 (Fig. 3, B and C). The water molecule is well defined with a very low temperature factor of 7.8 Å2 compared with the average of 33.8 Å2 for all water molecules in the structure. In the wild-type structure, the equivalent water molecule has a temperature factor of 21.4 Å2 compared with an average for all water molecules of 39.8 Å2. This indicates that the water molecule is engaged in stabilization of the activation pocket of FVIIaDVQ resulting in a more buried Ile153. Structural elements surrounding W33 in the binding pocket, including activation loop 1 (Gly285–Ala294) of the activation domain, are all stabilized in FVIIaDVQ-sTF-(1–209) compared with wild-type as judged from lower temperature factors. Val296 is spatially located between mutated residues Asp158 and Asp212 positioned in the Ca2+-binding loop and, interestingly, the side chain of Asp212 is slightly more extended toward the hydrophobic side chain of Val296 compared with when Glu296 is present (in FVIIa). Thus, a potential electrostatic repulsion between a residue in the Ca2+-binding loop (Asp212) and a residue immediately succeeding activation loop 1 (Glu296) is eliminated by introducing valine in position 296. A hydrogen bond observed in the wild-type structure between His211 in the Ca2+-binding loop and Glu296 was prevented as well by the E296V mutation, leaving the Ca2+-binding loop without side chain interactions with the Gly283– Met298 loop.

FIGURE 3.

Highlight of residues surrounding positions 158, 296, and 298 in the protease domain in the structures of FVIIaDVQ (2.2 Å) and wild-type FVIIa (2.0 Å; PDB code 1DAN). A,2Fo – Fc electron density shown at 1σ (blue) and 2σ (red). B, the introduced residues Asp158 and Gln298 are part of a distinct hydrogen bond network, including water molecule W33 (in red), leading to increased stabilization and burial of the N terminus and establishment of the salt bridge between Ile153 and Asp343. Such a network is not present in the wild-type structure (C) where Met298 occupies a central position via its hydrophobic nature. Note changes in the interface between the Ca2+-binding loop (Ca2+ shown as a green sphere) and the activation loop via the Val296 mutation, including lack of a hydrogen bond with His211 and a changed rotamer state of Asp212. Root mean square displacements (Cα) of the Ca2+-binding loops of the mutant structure versus the wild-type structure were 0.41 Å compared with an overall of 0.43 Å for the heavy chains.

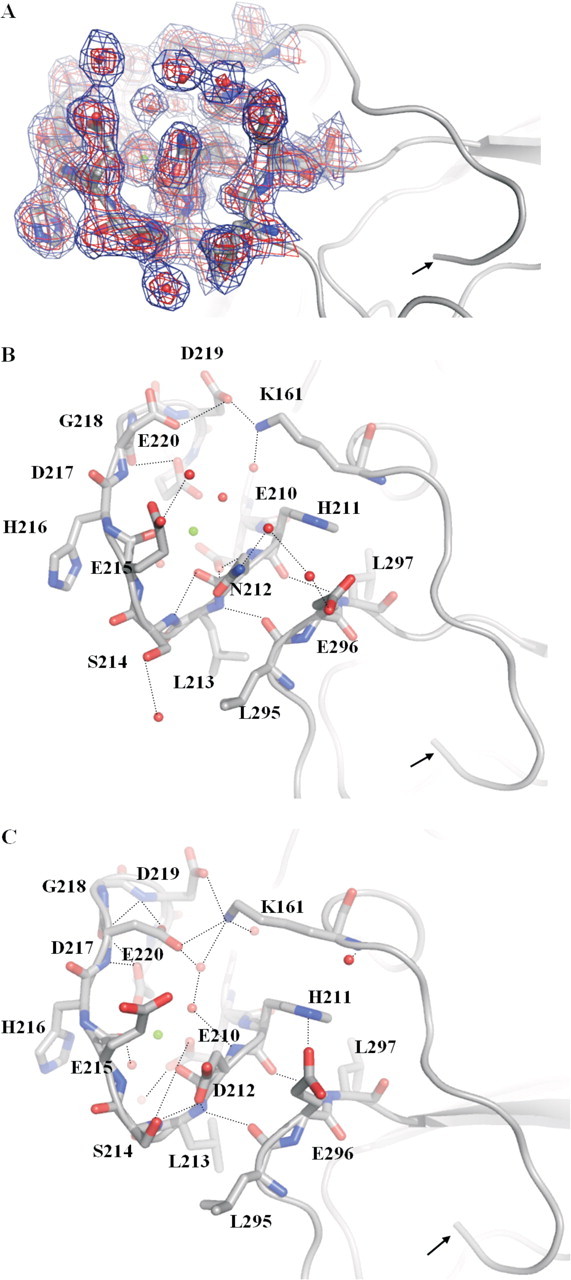

In the structure of FVIIaD212N-sTF-(1–209), residue Asn212 was identified in a conformation only slightly different from that of wild-type residue Asp212 (Fig. 4A). Altered hydrogen bond networks surrounding the mutated residue, viz. interaction with the neighboring Ser214, as well as other more distant parts of the loop were apparent (Fig. 4, B and C). A well defined network of water molecules (temperature factors: 24–29 Å2) in weak hydrogen binding distances (3.2–3.5 Å) of Glu296 and Asn212 could be observed. A hydrogen bond network between these residues might explain how the Asn mutation relieves the charge tension between side chains 212 and 296, but must be treated with caution due to the lower resolution of the x-ray data.

FIGURE 4.

Highlight of residues in the Ca2+-binding loop of the protease domain in the structures of FVIIaD212N (A and B; 2.7 Å) and wild-type FVIIa (C; 2.0 Å; PDB code 1DAN). The N terminus is indicated with an arrow and hydrogen bonds shown by dotted lines.2Fo – Fc electron density maps are shown at 1σ (blue) and 2σ (red). The mutant structure shows changes of hydrogen bond networks in the Ca2+-binding loop (Ca2+ shown as a green sphere), for example, surrounding mutated residue Asn212 and Ser214 and Glu296. A hydrogen bond is abolished between Asn212 and Ser214 because of a side chain movement of Ser214 in the mutant structure. A hydrogen bond network is introduced between Asn212, Glu296, and two strongly defined water molecules. In the wild-type structure, Asp212 and Glu296 are not in an electrostatically optimal configuration because of charge repulsion and the conformations of the two residues are slightly changed in the mutant structure. A distinct side chain movement of Asp217 can be observed as well. In turn, a hydrogen bond between Lys161 and Asp217 is lost, whereas bonding to Asp219 is strengthened: Asp219 to Lys161 is 2.6 Å in the mutant structure (see B) versus 3.9 Å in the wild-type structure (see C). Root mean square displacements (Cα) of the Ca2+-binding loop of the mutant structure versus the wild structure were 0.74 Å compared with an overall of 0.65 Å for the heavy chains.

The changed conformation of the Ca2+-binding loop appears to indirectly stabilize the activation domain and thus to mature the active site. It is important to mention that the main chain hydrogen bonds (Leu213:N to Leu295:CO and His211:CO to Val297:N) tethering the Ca2+ loop to the strand harboring position 296 were only slightly changed in the FVIIaD212N and FVIIaDVQ structures compared with the FVIIa structure. The mutated residue Asn212 appeared to influence residues further away in the Ca2+-binding loop, including residues Asp217, Asp219, and Glu220, as well as Lys161 positioned in the N-terminal tail (Fig. 4, B and C, for details).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have investigated the zymogenicity of FVIIa and factors that influence the insertion of the N terminus. We have identified residue Asp212, located in the Ca2+-binding loop of the protease domain, as yet another determinant for the zymogen-like state of FVIIa, like the Val158-Glu296-Met298 motif. Asn introduced into FVIIaD212N leads to a more buried N terminus and a more mature active site as judged from faster AT inhibition and more efficient substrate cleavage. Thus, substituting these four residues shifts the conformational equilibrium toward the catalytically competent form of FVIIa. In structures of related coagulation factors, like thrombin (PDB code 1EB1), FXa (PDB code 1XKA), and FXIa (PDB code 1XX9), these four positions are occupied by amino acids that support hydrogen bond networks and we show that they can be accommodated into FVIIa with improved catalytic function as the outcome. X-ray crystallography confirmed an earlier finding that the higher intrinsic activity of FVIIaDVQ correlates with increased tethering of the N-terminal tail and more stable insertion of the N terminus (17, 20), structurally explicable by a hydrogen bond network established by the mutations V158D and M298Q. Only FVIIa has an Asp residue in what corresponds to position 212, whereas FIXa, FXa, and FXIa all have Asn (Ser in thrombin). In the constitutively active enzyme FXa, Asn and Arg in positions corresponding to 212 and 296, respectively, in FVIIa, establish a hydrogen bond network similar to that observed in the FVIIaD212N structure. Interestingly, an apparent Km effect on FX activation for FVIIaD212N could be observed, which is in agreement with the reported proteolytic activity of FVIIaD212A in the presence of sTF (38). This indicates that not only is Asp212 a zymogenicity-determining residue in FVIIa, but that it also is part of an exosite located in the Ca2+-binding loop.

We have previously shown that mutation E296V reduces the Ca2+ dependence of FVIIa, whereas at the same time slightly increases the burial of the N terminus, the maturation of the active site, and the amidolytic activity (20). As observed in the FVIIaDVQ structure, mutation E296V is indeed responsible for the decreased calcium dependence by abolishing side chain interactions with the Ca2+-binding loop that potentially affect activation loop 1. The functionality of Glu296 appears linked to Asp212 via charge repulsion. It has also been shown that Glu296 is linked to maturation of the catalytic cleft using an exosite-directed antibody (21, 22) whose inhibitory effect was abolished by the E296A mutation. Moreover, inhibitor binding to the active site of FVIIa appears to induce a conformational change of the Glu296 side chain.

Because we lack a zymogen-like FVIIa structure, with and without Ca2+ bound, the conformational states of Glu296 and Asp212 along with the activation domain and an unoccupied Glu210–Glu220 loop are unknown. However, the reciprocal impact of the two residues demonstrates how the interface between the Ca2+-binding loop and the tip of activation loop 1 affects N-terminal insertion. Activation loop 1 is a part of the canonical activation domain of trypsin-like proteases and it changes from a flexible to a stabilized conformation upon activation (7, 8). This loop in FVIIa has indirectly been shown to become stabilized upon TF binding as judged from decreased deuterium exchange rates of peptic fragments (40, 41). A peptide comprising residues 207–220 was shown to have a markedly reduced exchange rate upon binding to TF (corresponding to protection of two deuterons) (40). In FVIIaDVQ, the peptide-(207–220) shows an exchange rate without TF very similar to that observed for FVIIa/TF (41). This suggests that charge removal in position 296 stabilizes the hydrogen bond interactions leading to reduced Ca2+ dependence and enhanced activity.

Removal of Ca2+ reduces the activity of FVIIa to less than 10% (14), indicating the potentially essential charge-neutralizing and loop-stabilizing effects of a Ca2+ ion in the Glu210–Glu220 loop. Mutations D212N and E296V further alleviate the electrostatic tension. The Ca2+ effect is relatively large for FVIIa as compared with related enzymes, but still smaller than the effect of TF. Interestingly, when FVIIa has bound TF, Ca2+ appears to have lost its stimulatory action and only acts as a complex stabilizer (42). Ca2+ binding to FXa stimulates the amidolytic activity by 30–35%, which is significantly less than for FVIIa (43, 44). FIXa is also modestly stimulated (3-fold), and this has, like for FVIIa, been shown to be accompanied by insertion of the N terminus into the activation pocket (45). The degree of Ca2+-induced stimulation appears to correlate with the net charge of the Ca2+-binding loop and the nature of the side chain in what corresponds to position 212 in FVIIa.

The introduced Asn in position 212 in FVIIa apparently modulated another hydrogen bond network, namely between Asp217 and Asp219 in the Ca2+-binding loop and Lys161 in the N-terminal tail. Lys161 links the N-terminal tail to the Ca2+-binding loop and appears to be involved in the Ca2+-dependent maturation of the active site of FVIIa. Indeed, mutating Lys161 to Ala results in a significant decrease in both proteolytic (39) and amidolytic activity as observed here. The effects of mutating either Asp217 or Asp219 were less pronounced, indicating that some interaction with Lys161 is retained. The effect of the K161A mutation is not sufficient to explain the entire effect of depleting FVIIa of Ca2+. The FVIIaD212N variant displays normal Ca2+ dependence, indicating that the altered interactions between the Ca2+-binding loop and Lys161 and Glu296 observed in the structure are not entirely responsible for the Ca2+ effect.

The zymogen-like conformation of FVIIa is essential and allows for initiation of the blood coagulation cascade only upon binding to exposed TF at the site of vascular injury. Val158, Asp212, Glu296, and Met298 play significant roles in, but are not fully responsible for, maintaining this physiological control mechanism. Notably, the four residues are highly conserved between FVIIa from different species.

In this study, we have functionally and structurally characterized the variants FVIIaDVQ and FVIIaD212N, whose conformation of the free form is shifted toward the active state with increased intrinsic activities as the measurable consequence. Because the crystal structures were solved with inhibited enzymes bound to sTF, a direct correlation to the free, uninhibited structure of FVIIa, which is unknown, must be performed with caution. However, we do believe that the localized changes observed in the activation domain, which are considerably distant to the TF binding site and the active site, are significant when compared with the structure of wild-type FVIIa in complex with sTF and thus potentially can be translated into the conformational state of the catalytically competent, free forms of FVIIaDVQ and FVIIaD212N. This translation is supported by the similar extent of hydrogen exchange reductions of peptides 207–220 and 153–169 (the N-terminal peptide) in FVIIa and FVIIaDVQ upon TF binding, indicating that the local backbone structural differences between the two free FVIIa molecules in and around the activation domain appear to be retained in the presence of TF (41). Hence, the structures reveal that new hydrogen bond networks increase the connections between the large loop containing activation loop 1, the Ca2+-binding Glu210–Glu220 loop, and the N-terminal tail. These insights are useful for better understanding of the allosteric regulation of FVIIa.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hanne B. Rasmussen for fruitful discussion of the manuscript and Anette Østergaard and Lisbet L. Hansen for excellent technical help.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: FVII/VIIa, coagulation factor VII/VIIa; TF, tissue factor; AT, antithrombin; sTF-(1–209), soluble TF, residues 1–209; Z, benzyloxycarbonyl.

Amino acid sequence numbering (FVIIa, chymotrypsinogen) is as follows: 153, 16; 156, 19; 157, 20; 158, 21; 161, 24; 210, 70; 211, 71; 212, 72; 213, 73; 214, 74; 217, 77; 219, 79; 220, 80; 283, 140; 295, 153; 296, 154; 297, 155, 298, 156; 306, 164; 312, 170; 343, 194.

References

- 1.Østerud, B., and Rapaport, S. I. (1977) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 74 5260–5264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davie, E. W., Fujikawa, K., and Kisiel, W. (1991) Biochemistry 30 10363–10370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh, P. N. (2001) Thromb. Haemostasis 86 75–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalafatis, M., Egan, J. O., van't Veer, C., Cawthern, K. M., and Mann, K. G. (1997) Crit. Rev. Eukaryotic Gene Expression 7 241–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torbet, J. (1995) Thromb. Haemostasis 73 785–792 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brünger, A. T., Huber, R., and Karplus, M. (1987) Biochemistry 26 5153–5162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huber, R., and Bode, W. (1978) Acc. Chem. Res. 11 114–122 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bode, W., and Huber, R. (1976) FEBS Lett. 68 231–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banner, D. W., D'Arcy, A., Chene, C., Winkler, F. K., Guha, A., Konigsberg, W. H., Nemerson, Y., and Kirchhofer, D. (1996) Nature 380 41–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wildgoose, P., Foster, D., Schiødt, J., Wiberg, F. C., Birktoft, J. J., and Petersen, L. C. (1993) Biochemistry 32 114–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabharwal, A. K., Birktoft, J. J., Gorka, J., Wildgoose, P., Petersen, L. C., and Bajaj, S. P. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 15523–15530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bom, V. J. J., and Bertina, R. M. (1990) Biochem. J. 265 327–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komiyama, Y., Pedersen, A. H., and Kisiel, W. (1990) Biochemistry 29 9418–9425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Persson, E., and Petersen, L. C. (1995) Eur. J. Biochem. 234 293–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soejima, K., Mizuguchi, J., Yuguchi, M., Nakagaki, T., Higashi, S., and Iwanaga, S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 17229–17235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Persson, E., Bak, H., Østergaard, A., and Olsen, O. H. (2004) Biochem. J. 379 497–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Persson, E., Kjalke, M., and Olsen, O. H. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 13583–13588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrovan, R. J., and Ruf, W. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 6616–6620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrovan, R. J., and Ruf, W. (2002) Biochemistry 41 9302–9309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Persson, E., and Olsen, O. H. (2002) Eur. J. Biochem. 269 5950–5955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dickinson, C. D., Shobe, J., and Ruf, W. (1998) J. Mol. Biol. 277 959–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shobe, J., Dickinson, C. D., and Ruf, W. (1999) Biochemistry 38 2745–2751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Persson, E., and Nielsen, L. S. (1996) FEBS Lett. 385 241–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolt, G., Steenstrup, T. D., and Kristensen, C. (2007) Thromb. Haemostasis 98 988–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thim, L., Bjørn, S., Christensen, M., Nicolaisen, E. M., Lund-Hansen, T., Pedersen, A., and Hedner, U. (1988) Biochemistry 27 7785–7793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sørensen, B. B., Persson, E., Freskgård, P. O., Kjalke, M., Ezban, M., Williams, T., and Rao, L. V. M. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 11863–11868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freskgård, P.-O., Olsen, O. H., and Persson, E. (1996) Protein Sci. 5 1531–1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang, E., St. Charles, R., and Tulinsky, A. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 285 2089–2104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cerenius, Y., Stahl, K., Svensson, L. A., Ursby, T., Oskarsson, A., Albertsson, J., and Liljas, A. (2000) J. Synchrotron Radiat. 7 203–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kabsch, W. (1993) J. Appl. Cryst. 26 795–800 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vagin, A., and Teplyakov, A. (1997) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30 1022–1025 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collaborative Computational Project (1994) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50 760–76315299374 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emsley, P., and Cowtan, K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potterton, E., Briggs, P., Turkenburg, M., and Dodson, E. (2003) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59 1131–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeLano, W. L. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA

- 36.Lawson, J. H., Butenas, S., Ribarik, N., and Mann, K. G. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268 767–770 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rao, L. V., Rapaport, S. I., and Hoang, A. D. (1993) Blood 81 2600–2607 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dickinson, C. D., Kelly, C. R., and Ruf, W. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93 14379–14384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Higashi, S., Nishimura, H., Aita, K., and Iwanaga, S. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 18891–18898 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rand, K. D., Jørgensen, T. J., Olsen, O. H., Persson, E., Jensen, O. N., Stennicke, H. R., and Andersen, M. D. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 23018–23024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rand, K. D., Andersen, M. D., Olsen, O. H., Jørgensen, T. J., Østergaard, H., Jensen, O. N., Stennicke, H. R., and Persson, E. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 13378–13387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miyata, T., Funatsu, A., and Kato, H. (1995) J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 117 836–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherrill, G. B., Meade, J. B., Kalayanamit, T., Monroe, D. M., and Church, F. C. (1988) Thromb. Res. 52 53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rezaie, A. R., and Esmon, C. T. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 21495–21499 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt, A. E., Stewart, J. E., Mathur, A., Krishnaswamy, S., and Bajaj, S. P. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 350 78–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]