Abstract

A critical step in understanding the mode of action of insecticidal crystal toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis is their partitioning into membranes and, in particular, the insertion of the toxin into insect brush border membranes. The Umbrella and Penknife models predict that only α-helix 5 of domain I along with adjacent helices α-4 or α-6 insert into the brush border membranes because of their hydrophobic nature. By employing fluorescent-labeled cysteine mutations, we observe that all three domains of the toxin insert into the insect membrane. Using proteinase K protection assays, steady state fluorescence quenching measurements, and blue shift analysis of acrylodan-labeled cysteine mutants, we show that regions beyond those proposed by the two models insert into the membrane. Based on our studies, the only extended region that does not partition into the membrane is that of α-helix 1. Bioassays and voltage clamping studies show that all mutations examined, except certain domain II mutations in loop 2 (e.g. F371C and G374C), which disrupt membrane partitioning, retain their ability to form ion channels and toxicity in Manduca sexta larvae. This study confirms our earlier hypothesis that insertion of crystal toxin does not occur as separate helices alone, but virtually the entire molecule inserts as one or more units of the whole molecule.

Insecticidal crystal proteins produced by Bacillus thuringiensis are of great commercial potential in the field of agriculture and health (1) by targeting a wide spectrum of crop pests and vectors of human diseases. Cry1A toxins are active against lepidopteran insects, which include agricultural pests. The toxins are produced by the bacterium in the stationary phase as inactive crystal protoxins (1). Activation of the 130-kDa protoxin to a 65-kDa active toxin occurs in the alkaline environment of the lepidopteran midgut. Crystal structures of the active toxin show that the toxin has three domains that are conserved through all the crystal toxins (2–7). Domain I is an α-helical bundle made of seven antiparallel α-helices. Domain II is a globin-like, wedge-shaped prism made of antiparallel β-sheets ending in predominant Ω-loops, and domain III is a lectin-like β-sandwich. The protease-activated form of the toxin binds to receptors on the surface of the insect brush border membrane. Several receptors implicated in binding to the toxin include cadherins (8, 9), alkaline phosphatase, and one or more forms of aminopeptidases (10, 11), glycolipids (12, 13), and glycoproteins (14). The receptor-bound toxin has been proposed to undergo conformational changes (15, 16) before or after inserting into the membrane to form ion channels.

Studies focused on insertion of Cry1A toxins into the insect membrane have limited their studies to two α-helices of domain I of Cry1A toxins, α-helix 4 and 5 based on the theoretical Umbrella model of insertion proposed early in the 1980s (17). There has been little analysis of the other regions of the toxin. Several studies using nonspecific proteases to determine the presence of the toxin in the membrane (18, 19) have shown that almost the entire toxin is protected from the protease, but the extent of partitioning of the toxin into the membrane remains unmeasured.

Our current study spans the three domains of the toxin to identify specific regions that may be embedded into the insect membrane, including the regions of the toxin proposed by the Umbrella model and beyond. Biochemical protease protection assay and steady state fluorescence measurements using cysteine mutations in regions of three domains of Cry1Aa or Cry1Ab toxin show that all regions of the toxin studied except α-helix 1 are embedded into the membrane, although to different extents. Cry1Aa and Cry1Ab were both used as they show 89% identity in their sequence (20) and target similar insects.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Site-directed Mutagenesis and Expression—The cell culture containing the B. thuringiensis cry1Ab9-033 (21) was obtained from T. Yamamoto (Sandoz Agro Inc., Palo Alto, CA) and that for Cry1Aa was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (22). Uracil-containing template for Cry1Ab was obtained as described (23). Primers for site-directed mutagenesis were obtained from either Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., or Bioneer Inc. Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using mutagene M13 in vitro mutagenesis kit as described in the manufacturer's manual (Bio-Rad). Mutations were confirmed by double-stranded DNA sequencing performed at the Plant Microbe Genomics Facility, Ohio State University, Columbus.

Expression and Purification of the Toxin Mutants—Expression and preparation of the toxin were carried out as described earlier (24). Crystals were solubilized in 50 mm Na2CO3, pH 10.5, buffer to extract the protoxin and digested with 1:50 w/w of trypsin/crystal protein to yield the activated toxin. The toxins were purified using Sepharose Q ion exchange column and Sephacryl S300 and Superdex S200 gel filtration columns in series.

Preparation of Small Unilamellar Vesicles—Artificial phospholipids, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleyl-sn-glycerol-3-phophatidylcholine, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylethanolamine, and cholesterol (Avanti Polar lipids Inc.), used in the molar ratio of 7:2:1, similar in composition to lipids commonly in bilayer and vesicle formation of crystal toxins (2, 25, 26), were used to form SUV.2 Small unilamellar vesicles were prepared from a preparation of large multilamellar vesicles by using a Branson 2200 bath sonicator. The large multilamellar vesicle mixture free of any chloroform was sonicated in the water bath for 10-min intervals during which the solution turned less opaque. The size class of the SUV was measured on a DynaPro light scattering instrument (Wyatt Technologies.). SUV gave an average size range of 25–30 nm, which was reproducible from batch to batch analysis. Typical size ranges of SUV vary from 15 to 50 nm when obtained using this protocol (27).

Preparation of Brush Border Membrane Vesicles (BBMV)—Fourth instar larvae of Manduca sexta (Carolina Biologicals Supply Co.) were dissected using procedures described elsewhere (28). BBMV were prepared using modified a differential magnesium precipitation method (29). The final BBMV pellet was resuspended in a binding buffer (10 mm HEPES, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.4). Protein concentrations were estimated using Coomassie protein assay reagent (Pierce).

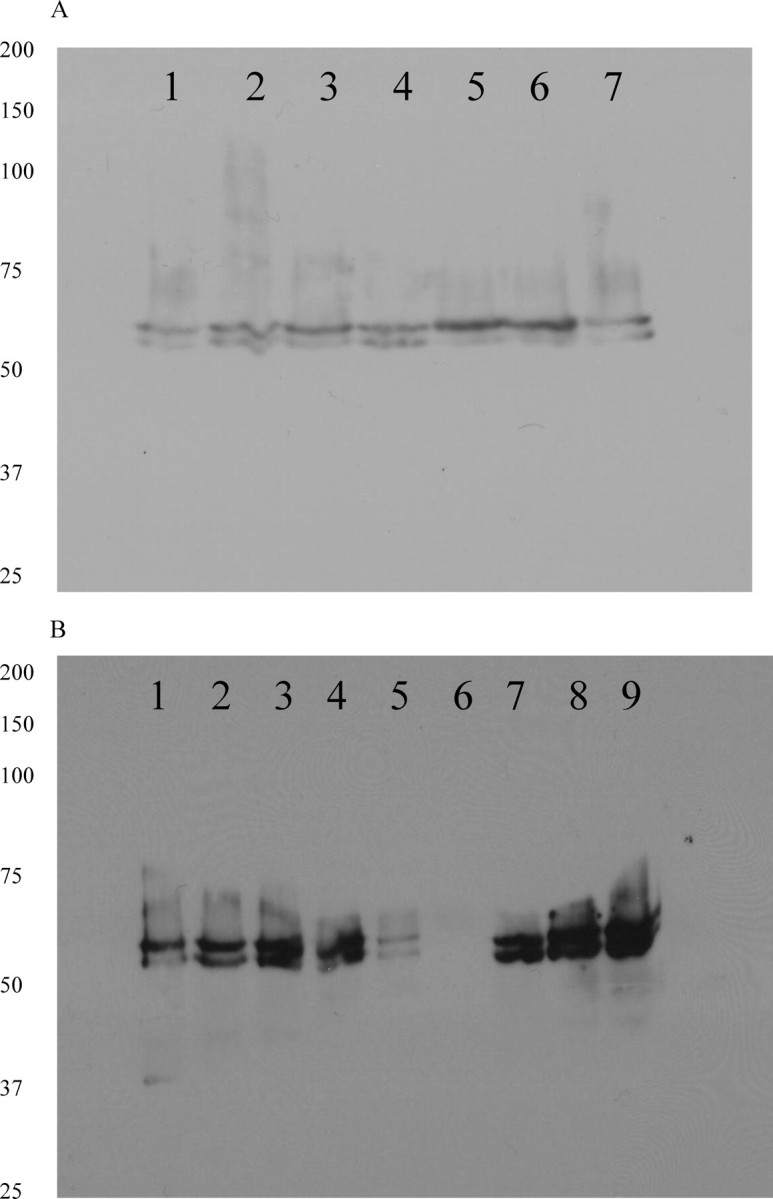

Proteinase K Protection Assays—Pure toxin was mixed with 10-fold excess of BBMV and incubated at 25 °C for 30 min after which proteinase K at 10-fold excess concentration of the toxin was added and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride was added to stop the reaction. The mixture was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min. The pellet was washed with 10 mm HEPES, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.4, then solubilized into 1% n-octyl β-d-glucopyranoside (Sigma), and boiled for 3–5 min before loading onto an 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and blotted using polyclonal anti-Cry1A rabbit antisera at a dilution of 1 in 10,000 and horseradish peroxidase-tagged goat anti-rabbit antisera at a dilution of 1 in 50,000 (Bio-Rad). Blots were visualized using chemiluminescent horseradish peroxidase substrate (Bio-Rad). The blots exposed to x-ray films for 10 s are depicted in the Fig. 1 and for 30 s in Fig. 2.

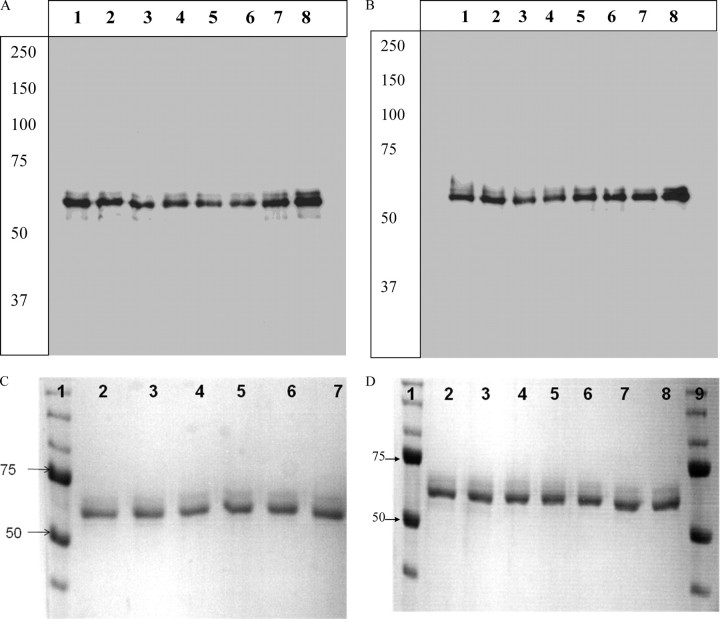

FIGURE 1.

A, Western blot analysis of purified Cry1A toxin used for proteinase K protection assays. Lane 1, Cry1Aa; lane 2, Cry1Ab; lane 3, Cry1AbL40C; lane 4, Cry1AaD62C; lane 5, Cry1AbV171C; lane 6, Cry1AbS191C; lane 7, Cry1AbL199C; lane 8, Cry1AbL215C. B, Western blot analysis of purified Cry1A toxin used for proteinase K protection assays. Lane 1, Cry1AbS279C; lane 2, Cry1AbS324C; lane 3, Cry1AbS364C; lane 4, Cry1AbF371W; lane 5, Cry1AbF371C; lane 6, Cry1AaE460C; lane 7, Cry1AaK489C; lane 8, Cry1AaI526C. C, purified domain I mutant proteins run on 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Lane 1, protein standard; lane 2, 1Ab L40C; lane 3, 1Aa D62C; lane 4, 1Ab V171C; lane 5, 1AbS191C; lane 6, 1Ab L199C; lane 7, 1Ab L215C. D, purified domain II and domain III mutants run on 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Lanes 1 and 9, protein standards; lane 2, 1Ab S279C; lane 3, 1Ab S324C; lane 4, 1Ab S364C; lane 5, 1Ab F371C; lane 6, 1AaE460C; lane 7, 1Aa K489C; lane 8, 1Aa I526C.

FIGURE 2.

A, Western blot analysis of 8% SDS-PAGE run of proteinase K protection assay of Cry1A mutants bound to BBMV. The mutants used are as follows: lane 1, Cry1Ab; lane 2, 1AbL40C; lane 3, 1AaD62C; lane 4, 1AbV171C; lane 5, 1AbS191C; lane 6, 1AbL199C; lane 7, 1AbL215C. B, Western blot analysis of 8% SDS-PAGE run of proteinase K protection assay of Cry1A mutants bound to BBMV. The mutants used are as follows: lane 1, Cry1Aa; lane 2, 1AbS279C; lane 3, 1AbS324C; lane 4, 1AbS364C; lane 5, 1AbF371W; lane 6, 1AbF371C;lane 7, 1AaE460C; lane 8, 1AaK489C; lane 9, 1AaI526C.

Labeling of Purified Cysteine Mutants with Probes—5-({2-[(Iodoacetyl)amino]ethyl}amino)naphthalene-1-sulfonic acid (1,5-IAEDANS) and 6-acryloyl-2-dimethyl-aminonaphthalene (acrylodan) were purchased from Invitrogen. Purified cysteine mutants were incubated with 10-fold molar excess of the probes and incubated in the dark overnight. Unbound label was removed using Sephadex G-50 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare). Purity of the protein was checked on 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and the efficiency of labeling was measured using the molar extinction coefficient of each probe.

Steady State Fluorescence Quenching Measurements—50 μg of 1,5-IAEDANS-labeled Cry1A toxin was mixed with 5 mg of SUV and incubated for 60 min. The bound toxin was separated from the unbound labeled toxin by passing the sample through a Sephadex G-100 column (GE Healthcare). Concentration of the SUV-bound protein was measured using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce) after delipidation of the proteins using a clean up kit (Pierce). Steady state fluorescence measurements of equal amounts of free and bound toxin were carried out in a Fluoromax-3 fluorimeter (JY Horiba). The sample was excited at a wavelength of 380 nm, and emission scan showed maximum fluorescence around 460 nm. The SUV-bound labeled toxin was treated with increasing aliquots of potassium iodide (KI) in thiosulfate (final concentration of 0.83 m) to test if the label on the bound toxin was further susceptible to collisional quenching in the aqueous environment. The percentage of quenching of fluorophore was calculated as the percentage ratio of the difference in the quantum yield before and after partitioning of the labeled protein to the total fluorescence of that free labeled protein in buffer.

Fluorescence “Blue Shift” Measurements—Acrylodan-labeled Cry1A toxin (50 μg) was treated with BBMV (500 μg) and incubated for 60 min. The bound toxin was separated from the unbound by centrifuging the sample at 15,000 × g. Proteinase K (500 μg) was added to the reaction and incubated for an additional 30 min. The sample was centrifuged again at 15,000 × g, and the resultant pellet was resuspended in binding buffer. Steady state fluorescence measurements of the labeled toxin, bound toxin before and after proteinase K treatment were carried out on Fluoromax-3 fluorimeter (JY Horiba). The samples were excited at 360 nm, and the fluorophore emission was read from 390 to 650 nm. Maximal emission wavelengths (λmax) of fluorescence of labeled toxin and toxin bound to BBMV before and after proteinase K treatment were recorded for each mutant. Each experiment was reproduced three times, and the average value of the λmax was recorded.

Toxicity Bioassays—Toxicity levels were determined by estimating the median lethal concentration (LC50) on M. sexta larvae using the diet surface contamination assay (24). Sixteen first instar larvae were used for each concentration of the toxin, and a total of six concentrations of each toxin were used. Mortalities were recorded after 5 days. The LC50 for each toxin was calculated by probit analysis using SoftTox (WindowsChem Software, Inc.).

Voltage Clamp Measurements of Cry1A Mutants—Inhibition of short circuit currents (Isc) was measured by clamping M. sexta midguts using procedures described earlier (28). Briefly, 100 ng of purified proteins were added to the lumen side of the gut stabilized in the buffer (30). Measurements were made on a DVC 1000 voltage/current clamp (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) connected to MacLab-4 (AD Instruments, Mountainview, CA). Data analysis was done using SigmaPlot version 10 (Systat Software Inc., Richmond, CA). The data were normalized to scale the percentage of short circuit current remaining. The slope of the linear region was used to measure the rate of ion transport in case of each mutant, and the lag time (T0) was also calculated as a measure of the rate of partitioning of the toxins into BBMV (28, 31, 32).

RESULTS

Expression and Purification of the Toxin Mutants—Cysteine scanning mutagenesis of several residues in the three domains of the toxin was successfully performed using the Kunkel method of mutagenesis (33) where uracil-rich single-stranded templates were annealed to primers and elongated in the presence of T7 DNA polymerase and T4 DNA ligase. The resulting products were transformed into DH5α cells (containing dUT-Pase) and screened for mutants. Proteins were expressed in DH5α cells under a “leaky” promoter. The resulting protoxins were run on an 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel to obtain a 130-kDa band (data not shown). Expressed proteins were digested with trypsin to yield an active 65-kDa form that was purified using ion exchange and gel filtration chromatography. The secondary structures of the mutants were compared with the wild type using a circular dichroism spectrophotometer. Only mutations with good expression level and whose secondary structure was not affected upon expression, as measured by circular dichroism, were used in this study. They are L40C, V171C, S191C, L199C, L215C, S279C, S324C, S364C, and F371C from Cry1Ab and D62C, E460C, K489C, and I526C from Cry1Aa. The mutations used span all the three domains of the toxin, and most of the chosen residues are conserved across Cry1Aa and Cry1Ab. Each purified toxin mutant (100 ng) used for the proteinase K protection assay has been blotted using anti Cry1A antibody as shown in Fig. 1. All Cry1A toxins in our hand produced a doublet band on the SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 1, C and D) upon purification from the crystals. Sequence analysis of the bands have shown that the doublet was a result of multiple trypsin sites at the C terminus of the active toxin close to each other and resulting from incomplete digestion of all molecules. We loaded 100 ng of toxin in Fig. 1 to indicate multiple bands in the Western blot.

Toxicity of Mutants—Biological activity of each mutant toxin was compared with that of the activity of the wild type toxins using a surface contamination method against first instar M. sexta larvae. The activity is reported as an LC50 value (concentration of the toxin required to kill 50% of the larvae) shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bioassay measurements of Cry1A toxins and their mutants on first instar larvae of M. sexta using surface contamination method

16 larvae were measured per concentration. Results were measured after 5 days of exposure to toxin and calculated as LC50 using probit analysis (Softox). WT indicates wild type.

| Toxin/mutant WT/domain I | LC50 | Toxin/mutant domains II and III | LC50 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ng/cm2 | ng/cm2 | ||

| Cry1Aa | 16.0 (8.0-25.3) | S279C | 22.0 (8.2-35.6) |

| Cry1Ab | 20.0 (7.5-31.7) | S324C | 19.8 (7.5-32.2) |

| L40C | 20.0 (7.0-33.4) | S364C | 25.6 (11.2-40.2) |

| D62C | 12.0 (4-20.2) | F371C | >2000a |

| V 171C | 20.0a (7.5-31.7) | F371W | 13a (8-20) |

| S191C | 28.2 (12.4-44.2) | E460C | 14.2 (5.6-23.0) |

| L199C | 32.4 (16.2-48.6) | K489C | 12.0 (3.8-21.0) |

| L215C | 25.4 (11.2-40.4) | I526C | 12.6 (3.0-21.4) |

Proteinase K Protection Assays—To test if the mutant toxin has retained the ability to insert into M. sexta BBMV, we digested the toxin bound to BBMV with proteinase K, a nonspecific protease. Western blot analyses show that even after treatment with 10-fold excess of proteinase K for 30 min, most of the mutants have retained an ∼60-kDa form of the toxin (Fig. 2). For the domain II residue Phe-371, its mutation to tryptophan protected it from the protease; however, its mutation to cysteine did not protect it. The effects of mutating Phe-371 on insertion of the toxin have been published. Phe-371 is a residue that has been studied for its ability to mediate insertion of the toxin into the membrane. The partitioning rate of every mutant into the brush border membrane and artificial membranes are not the same. We have seen that mutagenesis of Phe-371 to other residues in decreasing order of hydrophobicity have compromised its insertion ability (31, 34). Although mutation to Trp retained most of the toxicity of the toxin in these studies, the difference in the amount protected for this mutant (Fig. 2B) could be due to the ability of the toxin to partition only at a slower rate than wild type, for a fixed amount of time given for the toxin-membrane interaction in this assay. For mutations other than that to Trp, we see further decrease in insertion rate based on ion channel-forming abilities like voltage clamp studies and binding studies to BBMV (34). F371C was the most affected in these studies, and using the thiol probe acrylodan, it was shown that this mutation was completely ineffective in partitioning into brush border membranes (35).

Labeling Cry1A Mutants with Fluorophore—Purified cysteine mutants were labeled with acrylodan or IAEDANS and purified off free labels using gel filtration. The labeling efficiency was measured with each fluorophore and was found to be 95 ± 0.3% for acrylodan and 99 ± 0.5% for IAEDANS using their respective extinction coefficients. Circular dichroism analyses of the labeled mutants showed no variations in the spectra in the region of 200–250 nm indicating that the secondary structure has been retained upon labeling with either fluorophore (data not shown).

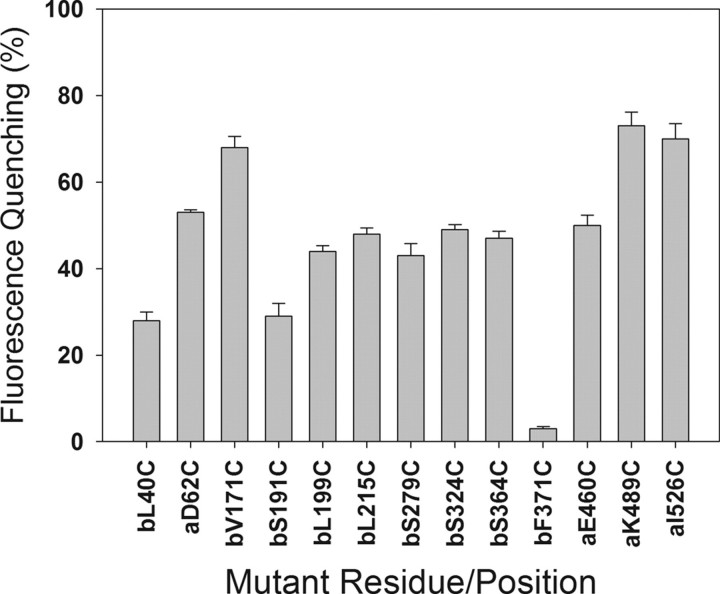

Quenching Analysis of Labeled Mutants in Artificial Vesicles—Using artificial SUV made of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleyl-sn-glycerol-3-phophatidylcholine, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylethanolamine, and cholesterol, the percentage of quenching of each cysteine mutant labeled to a fluorophore of the aminonaphthalene sulfonate family, IAEDANS, upon partitioning into the vesicles was measured. The IAEDANS fluorophore has a very high dipole moment and hence increased quantum yield of emission in an aqueous environment that gets quenched inside the SUV. Thus upon partitioning of the toxin into SUV, the fluorescence emission of IAEDANS is quenched. The percentage of quenching for each of the mutants in our study has been reported in Fig. 3. Results show that mutants in domain I (D62C, V171C, L199C, and L215C), domain II (S279C, S324C, and S364C), and domain III (K489C and I526C) all have about 50% or more of fluorescence quenched inside the SUV, whereas residues L40C and S191C in domain I have less than 50% quenching. Only F371C has almost no quenching into SUVs. Addition of KI solution to a final concentration of 0.83 m quenched the fluorescence of labeled toxin in buffer completely at the volumes used, but when mixed with the SUV-bound labeled toxins, there was no further quenching of the already quenched fluorescence of the vesicle-bound label, indicating that the hydrophilic collisional quencher was not able to access the label in the SUV-bound form.

FIGURE 3.

Percentage of quenching of fluorescence of 1,5-IAEDANS-tagged cysteine mutants calculated as (IIaq – ISUV)/Iaq, where Iaq is the quantum yield of fluorescence of the labeled mutants in aqueous buffer, and ISUV is the quantum yield of fluorescence of the labeled mutants in SUV.

“Blue Shift” Measurements of Acrylodan-labeled Mutants—Acrylodan is an environment-sensitive fluorophore that reacts with thiol groups of cysteines to form a covalent conjugate. Depending on the environment of the thiol group, there is a variation in the fluorescence emission from the molecule. Emission of the probe is low and at longer wavelengths (around 500 nm) in aqueous environments, whereas in a lipid environment like that of the BBMV, the emission occurs at much shorter wavelengths (around 460 nm). Emission from acrylodan-tagged mutants is dependent on its dipole moment, and is therefore different for different mutants depending on the exposure of the residue to the aqueous environment.

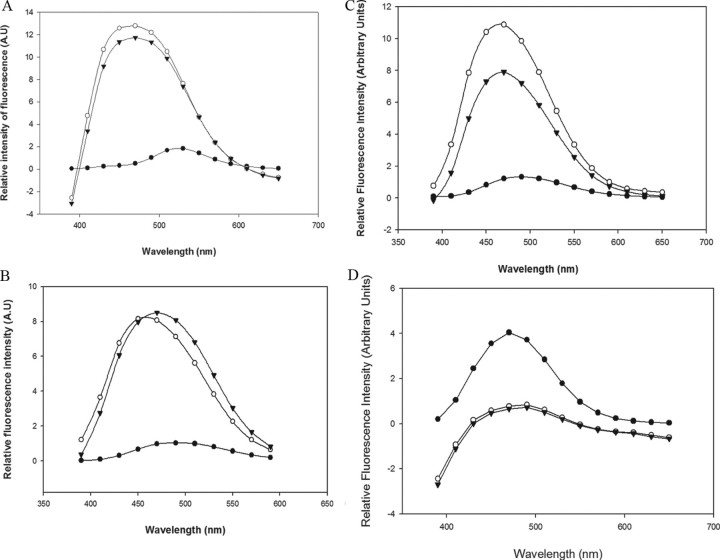

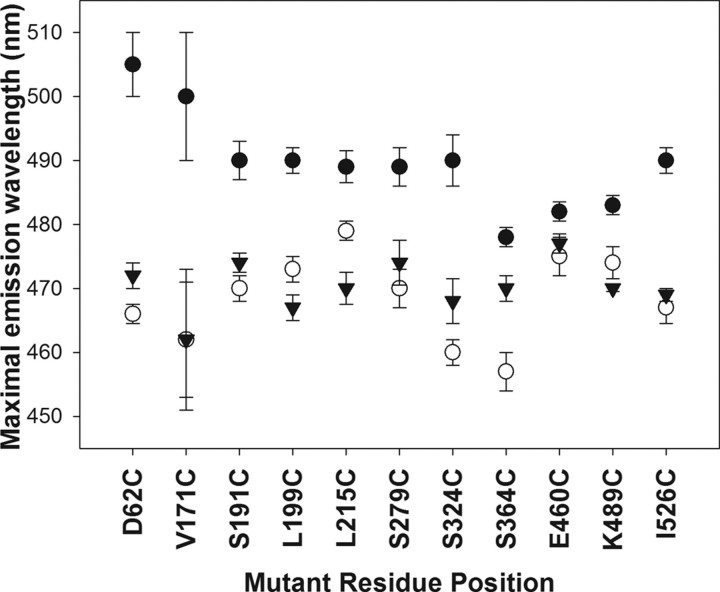

All our mutants, when tagged with the fluorophore, showed a maximal emission wavelength in aqueous environment around 480–500 nm. Upon binding to BBMV, the maximal emission wavelength shifted to a shorter wavelength for all of them, the extent of which was different for each mutant. This blue shift was retained for all the mutants even after treating the BBMV-bound labeled toxins with 100-fold excess of proteinase K. A–C in Fig. 5 are a representative spectra of mutants in domain I, II, and III, respectively, indicating the wavelength shift from longer to shorter wavelength under different environments for the label. The extent of blue shift was not the same before and after proteinase K treatment as indicated in Fig. 4. All these mutants were accompanied by an increase in the intensity of acrylodan fluorescence as seen in case of the representative spectra (Fig. 5, A–C). The only exceptions to this were Cry1Ab L40C, which showed decrease in its fluorescence emission (Fig. 5D), and Cry1Ab F371C, which block the protein from partitioning into the membrane (35).

FIGURE 5.

Steady state fluorescence measurement for the following acrylodan-labeled mutants. A, D62C (domain I); B, S324C (domain II); C, I526C (domain III); and D, L40C (domain I). • represents the fluorescence in buffer; ○ represents the fluorescence in BBMV before proteinase K treatment; and ▾ represents the fluorescence in BBMV after proteinase K treatment. y axis represents the relative intensity of fluorescence of the labeled mutant in buffer versus membranes and not absolute values of intensity.

FIGURE 4.

Blue shift in the maximal emission wavelength of each acrylodan-labeled mutant. The x axis indicates the name of each labeled mutant studied, and the y axis shows the maximal emission wavelength. Maximal emission wavelength of each mutant in aqueous carbonate buffer is indicated by •, in BBMV without any protease treatment is indicated by ○, and in BBMV after proteinase K treatment is indicated by ▾.

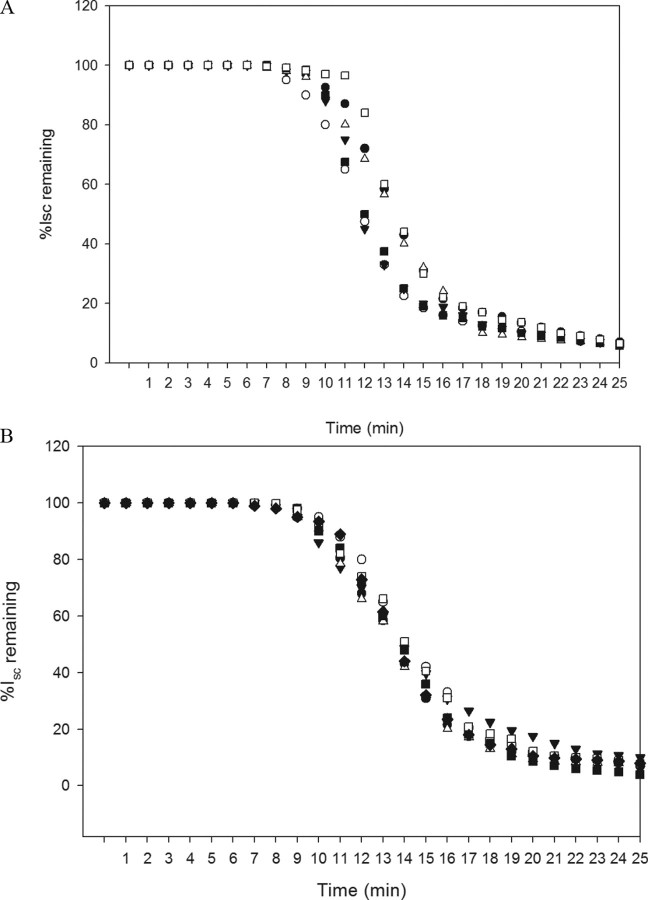

Voltage Clamp Measurements on Cry1A Mutants—To test the pore forming abilities of each mutant, we carried out voltage clamping of M. sexta midguts and measured the percentage of remaining short circuit current in the midgut after adding 100 ng of each toxin (Fig. 6). Slopes for the linear region of the drop in the Isc were calculated (Table 2 and Table 3). The voltage clamp response for Cry1Ab V171C and F371C are already reported earlier (35). The rate of ion transport was measured as the slope of the linear region of the drop in short circuit current for each of the mutations. We found that the rate of ion transport for mutants in domain I were overlapping with those of mutants in domain II and domain III indicating that pore formation was occurring at a similar rate. In addition the time lag (T0) values of 100 ng of all mutants ranged from 4.5 to 6.5 min for all the mutants while that of same amount of Cry1Aa and Cry1Ab was 5.0 min. This time lag is an indicator of the time the toxin takes, after adding to the membrane, to initiate pore formation, and in other words, it is the time of partitioning of the toxin into BBMV (28, 31, 32) suggesting that all our mutants partitioned into the membrane at a similar rate. The exception to this is Phe-371 when mutated to Cys or Ala, as reported in our earlier studies (34, 35), which is restored to almost wild type with tryptophan substitution. We have recently observed that G374C behaves as F371C (data not shown).

FIGURE 6.

A, voltage clamp response of Cry1Ab (•) to those of domain I mutants as follows: L40C (□), D62C (•), S191C (Δ), L199C (○), and L215C (▾). V171C has been reported earlier (35). B, voltage clamp response of Cry1Aa (•) to those in domain II mutants as follows: S279C (○), S324C (▾), S364C (Δ), E460C (•), K489C (□), and I526C (♦). F371C and F371W have been reported earlier (34, 35). The arrow indicates the time at which toxin was added to the stabilized midguts.

TABLE 2.

The rate of ion transport measured from the slope of the linear region of the decrease in short circuit current remaining (Isc) in M. sexta midguts for domain I mutants

| Sample | T0 | Slope |

|---|---|---|

| min | μA/min | |

| Cry1Ab | 4.0-5.0 | -12.0 ± 3.2 |

| 1AbL40C | 4.0-5.0 | -9.42 ± 2.33 |

| 1AaD62C | 6.0-7.0 | -10.72 ± 5.2 |

| 1AbS191C | 4.0-5.0 | -13.5 ± 2.92 |

| 1AbL199C | 5.0-6.0 | -15.1 ± 5.0 |

| 1AbL215C | 4.0-5.0 | -11.45 ± 0.75 |

TABLE 3.

The rate of ion transport measured from the slope of the linear region of the decrease in short circuit current remaining (Isc) in M. sexta midguts for domain II and III mutants

| Sample | T0 | Slope |

|---|---|---|

| min | μA/min | |

| Cry1Aa | 4.0-5.0 | -11.0 ± 1.7 |

| 1AbS279C | 5.0-6.0 | -10.3 ± 3.0 |

| 1AbS324C | 4.0-5.0 | -9.12 ± 0.89 |

| 1AbS364C | 5.0-6.0 | -11.0 ± 1.2 |

| 1AaE460C | 4.0-5.0 | -10.67 ± 1.67 |

| 1AaK489C | 5.0-6.0 | -9.58 ± 1.67 |

| 1AaI526C | 5.0-6.0 | -11.66 ± 3.0 |

DISCUSSION

Studies on the insertion of crystal toxins for the past 2 decades have focused on the mechanism by which the toxin forms ion channels in the brush border membrane vesicles of the insect midgut. Based on the crystal structure of Cry3Aa, Li et al. (3) proposed the Umbrella model of insertion of the toxin, which predicts that only α-helix 4 and 5 of domain I of the toxin would insert into the membrane because of the hydrophobic nature of α-helix 5. Subsequent studies on the toxin were extensively focused on the helices of domain I concluding that only those regions could partition into the membrane (36, 37) or line the pore (38). These studies did not address the fate of regions of the toxin other than the α-helices of domain I once the toxin is inserted. However, proteinase K protection studies (typically used for detecting the regions of membrane proteins inside lipid bilayer) have shown that a 60-kDa form (or higher molecular weight aggregate) of the toxin has been protected in membranes (15, 18, 19, 31, 35). This suggests that most of the toxin was likely to be embedded in the membrane. We mutated several residues across the three domains of the toxin to cysteine to determine whether these residues (and thereby the region of the toxin around them) are embedded into the membrane. Using fluorescence quenching and/or blue shift measurements, our results indicate that regions in all three domains of the toxin partition into the membrane.

This study used six mutations that span domain I, four mutations that span domain II, and three mutations that span domain III. Toxicity data showed that none of these mutations compromised the biological activity of the toxin (Table 1), and voltage clamp analysis (Tables 2 and 3) further indicates that all the mutations formed ion channels at a similar rate to wild type toxin.

Quenching data for IAEDANS-labeled mutants show that most of the labeled residues in all three domains of the toxin quenched their fluorescence upon partitioning into SUVs. Certain residues showed more quenching indicating that the label attached to those residues were in a relatively more hydrophobic environment as compared with those that showed less quenching. That the quenching was because of the label being in SUV was confirmed by the lack of any further quenching by the hydrophilic quencher, KI, added to the SUV-bound labeled toxin. An alternative possibility for the quenching of IAEDANS-labeled toxin is that the quenching could be due to hydrophobic environment generated by the toxin molecules itself upon self-aggregation or self-oligomerization. We have examined several IAEDANS-labeled toxins using in vitro self-aggregation in low ionic strength buffers (39). None of these labeled toxins showed significant quenching upon aggregation (data not shown).

A second possibility for the quenching of IAEDANS-labeled toxin in SUV is the possibility that SUVs do not mimic the natural BBMV environment where receptors play a role in determining the regions of the toxin that would be buried in the membrane. However, when IAEDANS-labeled toxin was used in natural BBMV, all labeled positions, except F371C, were quenched in the 80–90% range (data not shown). The result that the label was quenched in presence of SUV in mutants from all three domains suggests that more than two helices of domain I of the toxin are bound to the vesicles in the hydrophobic environment.

To verify the above observations with IAEDANS, we chose the chromophore acrylodan that undergoes enhanced fluorescence and a spectral blue shift upon entering a hydrophobic environment. Each cysteine mutant used in the study except L40C (on α-helix 1) and F371C (which blocks membrane partitioning of the whole toxin into the membrane (35)) showed a blue shift in its fluorescence upon binding to BBMV. We observed that not only regions of domain I insert into the brush border membrane, as predicted by the models in question, but that regions of domain II and domain III used in the study also inserted successfully into the membrane. In these experiments, we were able to circumvent any blue shift that might have occurred due to self-aggregation or oligomerization of the toxin outside the membrane by incorporating an additional step by measuring the fluorescence of toxin-treated vesicles before and after treating them with proteinase K for each mutant. This treatment enabled us to confirm that the region of the toxin to which the labeled toxin was bound was inserted into the membrane bilayer and was not in a hydrophobic environment outside the membrane. The extent of blue shift seen with each of the mutants before and after the proteinase K treatment was different. The “red” end of the spectrum (the environment that the labeled toxin is exposed to in the buffer) varies for each mutant depending on the polarity of the environment for that residue of the toxin. The extent of blue shift that each toxin undergoes indicates the change in the polarity of the environment that the toxin is exposed to upon insertion into the membrane. Domain I residues D62C and V171C had the greatest shift, whereas residues in domain II (S324C) and domain III (I526C) also underwent a significant blue shift in its fluorescence even after proteinase K treatment of the vesicles. Blue shifts of fluorescence in case of all other proteinase K-treated mutants indicate that regions of the toxin around those residues were also buried in the membrane. The quantum yield of fluorescence in all these mutants was also increased when the toxin was in BBMV compared when they were in buffer. Proteinase K treatment of labeled residue L40C showed a complete loss in fluorescence upon binding to BBMV indicating that the region of α-helix 1 is not present in the membrane. SDS-PAGE of the proteinase K-protected mutant L40C showed an intact 60-kDa form of the toxin indicating that only the region around that residue (α-helix 1) was vulnerable to the protease, and the rest of the toxin in this mutant was protected intact inside the membrane. Voltage clamping of the mutant also generated a similar rate of formation of ion channels as the wild type (Fig. 6). In case of Phe-371, our previous studies (35) show that the residue is involved in post-receptor binding processing, and therefore its mutation to smaller amino acids like alanine or cysteine prevents the insertion of the toxin, whereas replacement to tryptophan protects the toxin from proteinase K as shown in Fig. 2 and by earlier studies (23). We are further investigating the specific role of Phe-371 in mediating membrane insertion.

Our fluorescence partitioning data are complemented by electrophysiological analysis of all the mutants using voltage clamping of M. sexta midguts. Measurements of the rate of partitioning (T0) and the rate of ion channel formation (μA/min) for each mutant from domains I, II, or III showed that all mutants were able to partition and form ion channels at a similar rate. The data suggest that the entry of the toxin into brush border membranes may be more likely at the same rate or together for each domain, i.e. the entire toxin molecule rather than isolated regions may partition into the membrane.

Our observations do not support the Umbrella model of insertion of Cry1A toxin into brush border membrane vesicles, because we show that residues from domain I, domain II, and domain III insert into the membrane. These observations, providing evidence of specific regions from all three domains to the toxin that are buried in the membrane, are consistent with our previous study where we show domain II is involved in insertion (35). In summary this work supports the alternative model of insertion (32, 35, 40) that proposes almost the entire toxin of about 60 kDa to insert into the insect brush border membrane to mediate toxicity.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: SUV, small unilamelar vesicles; BBMV, brush border membrane vesicles; SUV, small unilamelar vesicles; IAEDANS, 5-((((2-iodoacetyl)amino)ethyl)amino)-naphthalene-1-sulfonic acid; acrylodan, 6-acryloyl-2-dimethyl-aminonapthalene.

References

- 1.Schnepf, E., Crickmore, N., VanRie, J., Lereclus, D., Baum, J., Feitelson, J., Zeigler, D. R., and Dean, D. H. (1998) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62 775–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grochulski, P., Masson, L., Borisova, S., Pusztai-Carey, M., Schwartz, J.-L., Brousseau, R., and Cygler, M. (1995) J. Mol. Biol. 254 447–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li, J., Carroll, J., and Ellar, D. J. (1991) Nature 353 815–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morse, R., Yamamoto, T., and Stroud, R. M. (2001) Structure (Lond.) 9 409–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galitsky, N., Cody, V., Wojtczak, A., Ghosh, D., Luft, J. R., Pangborn, W., and English, L. (2001) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 57 1101–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boonserm, P., Davis, P., Ellar, D. J., and Li, J. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 348 363–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boonserm, P., Mo, M., Angsuthanasombat, C., and Lescar, J. (2006) J. Bacteriol. 188 3391–3401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francis, B. R., and Bulla, L. A., Jr. (1997) Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 27 541–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hua, G., Jurat-Fuentes, J. L., and Adang, M. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 28051–28056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knight, P. J. K., Crickmore, N., and Ellar, D. J. (1994) Mol. Microbiol. 11 429–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sangadala, S., Walters, F. S., English, L. H., and Adang, M. J. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 10088–10092 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffitts, J. S., Whitacre, J. L., Stevens, D. E., and Aroian, R. V. (2001) Science 293 860–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffitts, J. S., Haslam, S. M., Yang, T., Garczynski, S. F., Mulloy, B., Morris, H., Cremer, P. S., Dell, A., Adang, M. J., and Aroian, R. V. (2005) Science 307 922–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valaitis, A. P., Jenkins, J. L., Lee, M. K., Dean, D. H., and Garner, K. J. (2001) Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 46 186–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aronson, A. I., Geng, C., and Wu, L. (1999) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65 2503–2507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bravo, A., Gómez, I., Conde, J., Muñoz-Garay, C., Sanchez, J., Miranda, R., Zhuang, M., Gill, S. S., and Soberón, M. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1667 38–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knowles, B. H. (1994) Adv. Insect. Physiol. 24 275–308 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aronson, A. (2000) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66 4568–4570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomimoto, K., Hayakawa, T., and Hori, H. (2006) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 144 413–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Höfte, H., and Whiteley, H. R. (1989) Microbiol. Rev. 53 242–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee, M. K., You, T. H., Curtiss, A., and Dean, D. H. (1996) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 229 139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schnepf, H. E., and Whiteley, H. R. (1981) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 78 2893–2897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajamohan, F., Alcantara, E., Lee, M. K., Chen, X. J., Curtiss, A., and Dean, D. H. (1995) J. Bacteriol. 177 2276–2282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, M. K., Milne, R. E., Ge, A. Z., and Dean, D. H. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267 3115–3121 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peyronnet, O., Vachon, V., Schwartz, J.-L., and Laprade, R. (2001) J. Membr. Biol. 184 45–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz, J.-L., Garneau, L., Savaria, D., Masson, L., Brousseau, R., and Rousseau, E. (1993) J. Membr. Biol. 132 53–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pitcher, W. H., III, and Huestis, W. H. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 296 1352–1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liebig, B., Stetson, D. L., and Dean, D. H. (1995) J. Insect Physiol. 41 17–22 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolfersberger, M., Lüthy, P., Maurer, A., Parenti, P., Sacchi, F. V., Giordana, B., and Hanozet, G. M. (1987) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 86 301–308 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chamberlin, M. E. (1994) Physiol. Zool. 67 82–94 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arnold, S., Curtiss, A., Dean, D. H., and Alzate, O. (2001) FEBS Lett. 490 70–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alzate, O., You, T., Claybon, M., Osorio, C., Curtiss, A., and Dean, D. H. (2006) Biochemistry 45 13597–13605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kunkel, T. A. (1985) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82 488–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajamohan, F., Cotrill, J. A., Gould, F., and Dean, D. H. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 2390–2397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nair, M. S., Liu, X. S., and Dean, D. H. (2008) Biochemistry 47 5814–5822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gazit, E., and Shai, Y. (1993) Biochemistry 32 3429–3436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gazit, E., LaRocca, P., Sansom, M. S. P., and Shai, Y. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95 12289–12294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masson, L., Tabashnik, B. E., Liu, Y.-B., Brousseau, R., and Schwartz, J.-L. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 31996–32000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masson, L., Mazza, A., Sangadala, S., Adang, M. J., and Brousseau, R. (2002) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1594 266–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loseva, O. I., Tiktopulo, E. I., Vasiliev, V. D., Nikulin, A. D., Dobritsa, A. P., and Potekhin, S. A. (2001) Biochemistry 40 14143–14151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]