Abstract

Heterotropic association of tissue transglutaminase (TG2) with extracellular matrix-associated fibronectin (FN) can restore the adhesion of fibroblasts when the integrin-mediated direct binding to FN is impaired using RGD-containing peptide. We demonstrate that the compensatory effect of the TG-FN complex in the presence of RGD-containing peptides is mediated by TG2 binding to the heparan sulfate chains of the syndecan-4 cell surface receptor. This binding mediates activation of protein kinase Cα (PKCα) and its subsequent interaction with β1 integrin since disruption of PKCα binding to β1 integrins with a cell-permeant competitive peptide inhibits cell adhesion and the associated actin stress fiber formation. Cell signaling by this process leads to the activation of focal adhesion kinase and ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinases. Fibroblasts deficient in Raf-1 do not respond fully to the TG-FN complex unless either the full-length kinase competent Raf-1 or the kinase-inactive domain of Raf-1 is reintroduced, indicating the involvement of the Raf-1 protein in the signaling mechanism. We propose a model for a novel RGD-independent cell adhesion process that could be important during tissue injury and/or remodeling whereby TG-FN binding to syndecan-4 activates PKCα leading to its association with β1 integrin, reinforcement of actin-stress fiber organization, and MAPK pathway activation.

Tissue transglutaminase (TG2)2 belongs to a family of enzymes that in the presence of Ca2+ catalyze the post-translational modification of proteins either by covalent cross-linking or through the incorporation of primary amines. TG2 has a GTP binding/hydrolysis site that negatively modulates the Ca2+-dependent transamidating activity of the enzyme by obstructing access to the active site (1). As a consequence, the enzyme is likely to be inactive under normal Ca2+ homeostasis. TG2 localizes mainly in the cytoplasm, yet recent reports also suggest its presence in the nucleus, mitochondria, at the cell surface, and in the extracellular matrix (ECM) (1–3). TG2 is translocated to the plasma membrane and was subsequently deposited into the ECM via a non-classical secretory mechanism reportedly dependent on active site conformation and on an intact N-terminal β-sandwich domain (4, 5) as well as on its possible association with integrins (6). Deposition of the enzyme into the ECM after cell damage and stress is important in the remodeling and/or stabilization of the several ECM proteins, such as FN (7, 8). FN is particularly interesting since TG2 binds to this ECM protein with high affinity promoting wide-ranging effects on cell-matrix interactions, including the regulation of cell adhesion and migration, matrix assembly, and adhesion-dependent signaling (6, 7, 9).

Cell adhesion to FN involves a series of coordinated signaling events orchestrated by numerous transmembrane receptors including the integrins and the superfamily of cell-surface proteoglycans (10, 11). The identity of the receptor-ligand pairing defines the composition of focal adhesions and the participants of intracellular signaling (10). For example, plating cells onto the principle adhesive ligands Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD), which bind to integrin receptors, was shown to induce the formation of nascent focal adhesions but failed to form stress fibers and/or a cytoskeletal network (12, 13). Only with the co-stimulation of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) by the addition of soluble FN heparin-binding polypeptide did cells form mature focal contacts on the cell binding domain of FN (12). The major group of HSPGs is the syndecans that have a distinctive pattern of expression characteristic for a particular cell type (11). Of the four members of the syndecan family, syndecan-4 is the only member that is ubiquitously expressed and has been shown to be present in focal contacts. By direct binding to FN, syndecan-4 cooperates with integrin α5β1 in focal adhesion formation and actin cytoskeleton organization as demonstrated in various anchorage-dependent cell lines (11, 14).

TG2 can enhance the cell attachment and spreading of a number of different cell types through the modification of ECM proteins by their cross-linking (15, 16). However, recent reports also describe a non-transamidating mechanism whereby TG2 acts as a novel cell adhesion protein (6, 17) thought to involve direct interaction with a variety of integrin receptors. The importance of TG2 as a wound response enzyme, particularly with respect to its role as a matrix-associated protein, is well reported (7, 18). Under these conditions, a TG2-rich FN matrix (TG-FN) may be found in which increased deposition of TG2 either by secretion from surrounding cells or via disruption of incoming red blood cells occurs at injury sites where TG2 binds to FN with high affinity. Using a TG-FN matrix or a cell-secreted TG2 rich matrix, we showed that this complex could restore loss of cell adhesion and promote cell survival in both fibroblasts and osteoblast after the inhibition of the classical FN RGD-dependent cell adhesion pathway mediated by α5β1 integrin receptors (19). Such a process would be important during tissue injury and during matrix remodeling where disruption of FN and other matrix proteins leads to generation of soluble RGD-containing peptides which can compete for matrix cell binding sites, potentially leading to anoikis (7, 20). We previously demonstrated that RGD-independent cell adhesion to the TG-FN complex did not require transamidating activity but induced the formation of focal adhesion contacts, the assembly of associated actin stress fibers, and FAK phosphorylation (19). In this previous study, we demonstrated that the digestion of cell surface heparan sulfate chains significantly reduced the cell adhesion to TG-FN after RGD inhibition, suggesting the involvement of a HSPG receptor (19).

Here we report that the TG-FN complex promotes RGD-independent cell adhesion through binding to the heparan sulfate chains of syndecan-4. This novel pathway requires interaction of PKCα with β1 integrin and induces FAK and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the ablation of c-Raf-1 diminishes the ability of a TG-FN matrix to rescue cell adhesion in the presence of RGD-containing peptides.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies—Human plasma fibronectin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The FN synthetic peptides GRGDTP and GRADSP were from Calbiochem. Integrin Sampler antibody kit containing rabbit anti-integrin β1,β3,β5 was purchased from Insight Biotechnology; anti-integrin α4 antibody (P1H4) was from Chemicon; mouse anti-human FAK, mouse anti-phospho-ERK, mouse anti-PKCα were from Santa Cruz; the mouse anti-α-tubulin, and rabbit anti-actin antibodies were from Sigma-Aldrich; anti-FAK Tyr(P)397 and Tyr(P)861 were from Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions and BIOSOURCE, respectively. The rabbit polyclonal anti-syndecan-4 was from Zymed Laboratories Inc. Purified guinea pig liver TG2 was purified according to Leblanc et al. (21). The GK-21 peptide (GENPIYKSAVTTVVNPKYEGK) and the scrambled control peptide (GTAKINEPYSVTVPYGEKNKV) were chemically synthesized in tandem with the antennapedia third helix sequence (RQIKIWFQNRRMKWKK) by Peptide Protein Research. The irreversible active-site directed inhibitor R283 (1,3-dimethyl-2-[(2-oxopropyl)thio] imidazolium chloride) (4, 22), was synthesized at Aston University.

Cell Lines—Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts transfected with TG2 cDNA under tetracycline repressible promoter were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium as we previously described (23). The CHO-K1 cell line was purchased from ATCC and grown in Ham's F-12 medium according to the supplier's instructions. Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts isolated from syndecan-4 wild type (wt)/knock out (ko) mice and β1 integrin wt/ko mice along with syndecan-4 and β1 integrin ko mouse embryonic fibroblasts stably transfected back with wild type syndecan-4 and β1 integrin cDNA, respectively (supplemental Table 1), were provided by Prof. M. J. Humphries (University of Manchester, Manchester, UK) and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium as published. The PKCα binding mutant syndecan-4 ko cells transfected with Y188L human syndecan-4 were cultured as described (24). The 3T3-like fibroblast cell lines derived from E12.5 Raf-1 ko and wt and stable Raf-1 ko cell clones expressing full-length kinase-competent of Raf-1 (KC3) or a kinase-dead domain of Raf-1 protein were gifts of Manuela Baccarini (University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria) and were cultured as described previously (25).

Cell Adhesion Assay—Cell adhesion assays were performed as described before (19). Briefly, tissue culture plastic was coated with 1 μg of FN per cm2 overnight at 4 °C. After blocking of the FN matrix in 3% (w/v) Marvel, 2 μg of guinea pig liver TG2 per cm2 was immobilized on FN matrix. Before experiments, cells were starved by the reduction of serum concentration to 2% (v/v) for 18 h before experiments. After the detachment of cells from their substratum with trypsin, they were washed twice in serum-free growth media, pretreated with GRGDTP and GRADSP control peptide, and seeded on matrices at a density of 6 × 104 cells/cm2. In adhesion assays with Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts transfected with TG2, phosphate-buffered saline containing 2 mm EDTA, pH 7.4, was used for non-enzymatic detachment, which enabled cells to retain the cell surface-associated TG2 (4). Based on previous toxicity findings (19), adhesion experiments were performed using 75–150 μg/ml RGD synthetic peptide, leading to partial inhibition in cell adhesion. In heparin treatment studies, bound FN was first incubated with heparin in a 60-fold excess of the FN before TG2 immobilization. The amount of immobilized TG2 on the heparin-blocked FN matrix was shown to be comparable with the untreated TG-FN matrix using a modified enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as described previously (19). Cells were allowed to attach for 20–40 min to minimize the secretion of any endogenous proteins. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained, and digital images per each sample were acquired as stated before (19). The cell attachment and spreading were quantified, and the number of cells per image was assessed as described previously (19).

Immunoblotting and Co-immunoprecipitation—Swiss cells grown to 70% confluency and serum-starved for 18 h were trypsinized and then plated onto 6-well plates coated with FN or TG-FN matrices at a density of 6 × 105 cells per well. After the treatment with RAD/RGD-containing peptides, cells were allowed to attach for 30 min. For detection of basal and tyrosine phosphorylation levels of MAPKs, cells were lysed by the addition of 50 μl of solubilization buffer (1% (v/v) Nonidet, 0.5% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, 1 mm benzamidine, 1 mm NaF, 1 mm Na3VO4, 0.1 mm PMSF and 1% (v/v) protein inhibitor mixture). Cell extracts were clarified by further centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min at 4 °C and stored at -70 °C. Equal amounts of protein were electrophoretically separated and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The nitrocellulose membranes were blocked and probed with the antibodies of interest as described previously (19). For co-immunoprecipitation, cells were plated onto TG-FN where the FN was first blocked with heparin as described above. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1% (v/v) protein inhibitor mixture (Sigma-Aldrich), 500 μm R283 TG2 specific inhibitor, and 50 mm Tri-HCl, pH 7.4, and put on ice for 30 min with occasional mixing. 200 μg of cell extract was then precleared for 1 h at 4 °C with nonspecific rabbit IgG followed by 90 min of incubation with 50 μl of protein A-Sepharose bead slurry on a rocking platform. Precleared cell lysates were then incubated with 0.5 μg of rabbit anti-syndecan-4 antibody for 90 min at 4 °C. Immune complexes were precipitated with 50 μl of protein A-Sepharose bead slurry for 2 h at 4 °C, washed with lysis buffer, and extracted in Laemmli sample buffer. Samples were resolved by 8% SDS gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and immunoprobed with mouse monoclonal anti-TG2 Cub7402 antibody (Lab Vision Corp.) or anti-β1 integrin antibody as described previously (4).

Immunofluorescence Staining—Subconfluent mouse embryonic fibroblasts were serum-starved for 16 h, harvested, and pretreated with 100 μg/ml GRADSP or GRGDTP peptides as described above. Cells were seeded in 8-well glass chamber slides (8 × 104 cells/well) previously coated with FN and TG-FN and allowed to attach and spread for 40 min. Cells were fixed and permeabilized as described previously (19). For staining of actin stress fibers, cells were blocked in phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 3% (w/v) bovine serum albumin and then incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled phalloidin (20 μg/ml) in blocking buffer. Coverslips were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium and using constant photomultiplier tube and section depth settings, nine random fields/sample were captured by Zeiss LSM510 laser confocal microscopy using Zeiss LSM Image Browser.

Statistics—Data were expressed as the mean ± S.D. The data shown are derived from mean of at least three experiments (n ≥ 3) undertaken in triplicate. The comparisons between the data sets were performed using Student's t test (two-tailed distribution with equal variance). Statistical significant difference between data sets was defined in the text by a p < 0.05 (two-sided).

RESULTS

FN-bound TG2 Requires Association with Cell Surface Heparan Sulfate Chains for RGD-independent Cell Adhesion—Our previous data (19) suggested an interaction between TG-FN complex and cell surface HSPG receptors in RGD-independent cell adhesion; however, the relative contribution of the two proteins to this process is not known. Heparin binding sites in FN that can be recognized by HSPG receptors were, therefore, blocked as described (26) by excess soluble heparin before TG2 immobilization. The ability of FN-bound TG2 (TG-FN) to mediate RGD-independent cell adhesion was then investigated. Attachment and spreading on FN alone was sensitive to heparin blocking (Fig. 1A). The heparin-blocked FN matrix, for example, could only support ∼75% of control cell adhesion seen on FN matrix alone. Inhibition of cell adhesion by RGD-containing peptides was also more effective on the heparin-blocked FN matrix. In contrast, once TG2 was immobilized on the heparin-blocked FN matrix, it compensated for the loss of cell adhesion both in the presence or absence of RGD peptide.

FIGURE 1.

TG2 bound to FN supports RGD-independent cell adhesion through heparan sulfate chains. Each data point corresponds to the mean percentage of attached cells (cell attachment) or the mean percentage of spread cells (cell spreading) ± S.D. of at least three separate experiments performed in triplicate. Total cells analyzed in control samples were ∼500. A, adhesion of Swiss 3T3 cells on FN and TG-FN2 matrices with or without heparin block in the presence of RAD or RGD (100 μg/ml) peptide. Cell attachment and spreading is expressed as the mean percentage of attachment of RAD-treated cells on the FN matrix without heparin block± S.D., which represents 100%. B and C, response of CHO-K1 wt and heparan sulfate-deficient mutant HS-CHO-K1 mutant cells to TG-FN matrix. CHO-K1 wt and HS-CHO-K1 cells in suspension were pretreated with RAD (150 μg/ml) and RGD (100 and 150 μg/ml) peptides before seeding on either FN or TG-FN. Mean percentage value of CHO-K1 wt attached and spread cells on FN ± S.D. (control) was set at 100%. Bar, 20 μm.

Evidence suggests that the protein ectodomain and the heparan sulfate chains of HSPGs can support cell attachment and spreading through distinct pathways (27–29). To further elucidate the nature of the TG-FN interaction with HSPGs, a well characterized CHO-K1 cell mutant totally deficient in heparan sulfate synthesis (HS-CHO-K1) was used in the cell adhesion assays (Fig. 1, B and C). Wild type and mutant CHO-K1 cells displayed a comparable cell attachment on FN and TG-FN matrix, but the HS-CHO-K1 cells failed to spread on these matrices. Incubation with RGD peptide effectively blocked cell adhesion of wt and mutant CHO-K1 cells on FN matrix. Although wt cells could restore RGD-impaired cell adhesion when plated on a TG-FN matrix, the heparan sulfate mutant cells limited attachment but failed to spread on TG-FN in the presence of RGD.

TG-FN Does Not Support RGD-independent Cell Adhesion in Syndecan-4 Null Fibroblasts—Although cells can adhere and spread on the integrin binding domain of FN (RGD and central binding domain of FN), they fail to form complete focal adhesion contacts and reorganize the actin cytoskeleton unless syndecan-4 is activated (12, 30). To test whether the ubiquitous syndecan-4 is the HSPG receptor responsible for RGD-independent cell adhesion on TG-FN, mouse embryonic fibroblasts isolated from syndecan-4 wild type (sdc4 wt) and knock out (sdc4 ko) mice were used in cell adhesion assays. sdc4 wt fibroblasts plated on the FN matrix became well attached and spread, whereas sdc4 ko fibroblasts exhibited a slight delay in attachment and spreading in the short-term adhesion assays (20 min) losing as much as 20% of the original cell adhesion to FN (p < 0.05, Fig. 2A). 1 h after seeding on FN, the percentage of sdc4 ko cells that are spread with organized actin stress fibers were not statistically different than the wild type cell line (Fig. 2, A and B). Syndecan-4 null cells did, however, exhibit a reduction in longitudinal stress fibers and formed stress fiber bundles that were more restricted to the cell periphery compared with the wild type. The RGD peptide reduced cell adhesion of sdc4 wt fibroblasts on FN up to 60% of the cell adhesion recorded on the FN matrix alone in the presence of RAD peptide (control values). Sdc4 ko cells appeared to be more sensitive to RGD inhibition, and cell attachment and spreading on FN was decreased by 70–80% that of control values, respectively (Fig. 2A). RGD-impaired cell adhesion and the observed diffused actin cytoskeletal architecture was rescued only in the sdc4 wt cells seeded on the TG2-bound FN matrix, whereas sdc4 ko cells failed to respond to this matrix. To confirm that the perturbation of RGD-independent cell adhesion of sdc4 ko fibroblasts on TG-FN was because of a deficiency in syndecan-4 expression, sdc4 ko fibroblasts were transfected with syndecan-4 cDNA (sdc4 ab) or empty vector (sdc4 vec) (supplemental Fig. 1) (24). The reintroduction of syndecan-4 to sdc4 ko fibroblasts rescued the delayed cell attachment and spreading on FN (Fig. 2A) and enabled formation of typical actin stress fibers on FN (Fig. 2B). Importantly, sdc4 ab cells were able to respond to TG-FN matrix and mediate RGD-independent cell adhesion with well organized actin stress fibers.

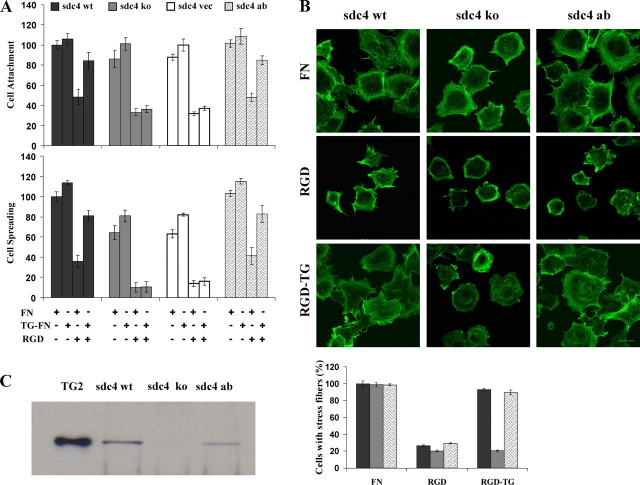

FIGURE 2.

The selective loss of syndecan-4 abolishes the TG-FN2-mediated RGD-independent cell adhesion. The percentage of attached cells or the percentage of spread cells ± S.D. shown are from the mean of at least three independent experiments, performed in triplicate. Total number of cells analyzed per experiment in control samples was ∼340. A, syndecan-4 wild type (sdc4 wt) and knock out (sdc4 ko) fibroblasts and syndecan-4 ko fibroblasts stably transfected with human syndecan-4 cDNA (sdc4 ab) or mock vector (sdc4 vec) were treated with RAD or RGD peptide (100 μg/ml) and seeded on FN and TG-FN matrices for 20 min. The mean cell attachment and spreading values were expressed as the percentage of control values of sdc4 wt cells seed on FN (which represents 100%) ± S.D. in the presence of RAD. B, actin stress fiber formation in sdc4 wt, ko, and ab cells on TG-FN in the presence of RGD peptide. Cells were treated with 100 μg/ml RAD and RGD peptide and seeded on FN and TG-FN matrices (FN, RGD, and RGD-TG, respectively), and actin stress fiber formation was visualized as described under “Experimental Procedures.” At least 150 cells were imaged for the control sdc4 wt cells seeded on FN in the presence of RAD peptide. Data shown are from a representative experiment, indicating the mean percentage of cells with formed actin stress fibers expressed as percentage of control values. Bar, 20 μm. C, lysates of cells samples were immunoprecipitated with anti-syndecan-4 and Western-blotted for TG2 (75kDa) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” TG2 isolated from guinea pig liver (TG2) was loaded to the first lane as the internal standard.

To show direct interaction of TG2 with syndecan-4 during RGD-independent cell adhesion, we immunoprecipitated the syndecan-4 TG2 complex. For this purpose, sdc4 wt, sdc4 ko, and sdc4 ab cells were treated with the RGD-containing peptide and seeded on a heparin-blocked FN matrix to which TG2 was bound. Thereby, we blocked the interaction of syndecan-4 with the heparin binding sites in FN, leaving only TG2 to associate with the receptor. Immunoprecipitation of syndecan-4 followed by immunoblotting for TG2 revealed the coimmunoprecipitation of TG2 (Fig. 2C), further confirming that TG2 in the TG-FN complex interacts directly with syndecan-4 to mediate an RGD-independent cell adhesion.

PKCα Activity and Its Interaction with β1 Integrins Is Essential in RGD-independent Cell Adhesion Signaling—Engagement of syndecan-4 with ECM proteins recruits PKCα to the plasma membrane and activates this serine-threonine kinase through a direct interaction between the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor and the catalytic domain of the enzyme (31). The inhibition of PKCα with the specific inhibitor Go6976 reduces the adhesion of human osteoblasts (19) and Swiss 3T3 (supplemental Fig. 2A) to FN and blocked the RGD-independent cell attachment and spreading in response to TG-FN, signifying the importance of this kinase in the signaling process. In addition, membrane fractionation experiments showed that the decrease in PKCα membrane levels in cells seeded on FN due to RGD inhibition was pulled back nearly to control levels when cells were seeded on TG-FN matrix (supplemental Fig. 2B).

To further confirm the involvement of syndecan-4-dependent PKCα regulation in RGD-independent cell adhesion signaling, we performed cell adhesion experiments using syndecan-4 ko cells expressing a PKCα binding mutant syndecan-4 (sdc4 Y188L) (24). sdc4 Y188L fibroblasts demonstrated similar adhesion on FN and TG-FN to sdc4 ko cells in that they failed to attach and spread on TG-FN in the presence of RGD (Fig. 3A). This result suggested that inhibition of the syndecan-4-dependent PKCα activation and membrane translocation by TG-FN abolishes the TG-FN-mediated RGD-independent cell adhesion.

FIGURE 3.

The importance of PKCα activity in RGD-independent cell adhesion on TG-FN matrix. A, syndecan-4 wild type (sdc4 wt) and knock out fibroblasts expressing Y188L mutant syndecan-4 (sdc4 Y188L) were plated on FN and TG-FN matrices in the presence of control RAD and RGD peptide (100 μg/ml). Mean percentage value of sdc4 wt cells attached and spread on FN in the presence of RAD ± S.D. (control) was used as 100%. B, site-directed disruption of PKCα and -β1 integrin interaction ablates the RGD-independent cell adhesion in response to TG-FN. Swiss 3T3 cell monolayers were preincubated with 8 μm scrambled CP and GK21 peptide (in serum free medium) for 1 h and seeded on FN and TG-FN matrices after RAD and RGD (100 μg/ml) peptide treatment. Mean percentage value of non-treated (NT) attached and spread cells on FN in the presence of RAD ± S.D. (control) was used as 100%. C, PKCα and β1 integrin cross-talk is necessary for the formation of actin-stress fibers during the RGD-independent cell-adhesion. CP- and GK21-treated Swiss 3T3 cells on FN and TG-FN matrices were scored for actin stress fiber formation in the presence of RAD and RGD peptides. The mean percentage ± S.D. of cells, which formed mature stress fibers, is shown.

Syndecan-4 signals cooperatively with integrin during integrin-mediated cell adhesion on FN. Hypothetically, β1 integrins might, therefore, also be involved in TG-FN-mediated, RGD-independent cell adhesion but via a process involving insideout signaling. Although the mechanism behind syndecan-4 and β1 integrin cross-talk remains to be revealed, evidence suggests PKCα is a possible link protein between the two receptors (24, 32–34). The PKCα binding site on β1 integrin has been mapped in the distal region of β1 cytoplasmic tail (amino acids 783–803). Based on this sequence, a 21-amino acid peptide (GK-21) mimicking the β1 cytoplasmic tail was synthesized in tandem with the antennapedia third helix sequence and shown to perturb PKCα and β1 integrin interaction and block cancer cell chemotaxis by hindering PKCα (35). Using a similar approach, Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts were pretreated with cell-permeable peptide GK-21 (permeability shown in the supplemental Fig. 2B) and scrambled control peptide (CP) before plating on FN and TG-FN matrices in the presence of RGD and RAD-containing peptides. Disruption of PKCα interaction with β1 integrins led to a significant (30%) decrease in cell adhesion on FN (p < 0.05), but more importantly, it ablated the RGD-independent cell adhesion on TG-FN (Fig. 3B). Immunofluorescence visualization of the actin stress fibers by confocal microscopy revealed that GK-21 treatment resulted in a less well developed actin cytoskeleton structure in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts on FN. Only 60% of GK-21-treated cells assembled actin stress fibers on FN that were somewhat less dense than those seen in CP-treated cells on FN (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, GK-21-treated cells adhering to TG-FN did not show organized stress fibers after RGD inhibition compared with CP-treated cells, which exhibited stress fiber assembly.

TG-FN-mediated RGD-independent Cell Adhesion Requires the Activation of β1 Integrins—To establish a role for β1 integrins in the TG-FN-mediated RGD-independent cell response, β1 integrin null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (β1 ko) and β1 ko cells transfected with β1 integrin cDNA (β1 ab) and empty vector (β1 vec) (36) were used. Because TG2 can associate with other β integrins like β3 (6) and β5 (37), the levels of these integrins were measured and found to be comparable among these cells (supplemental Fig. 3 and Table 1). The β1 ko and β1 vec cells displayed a 2-fold reduction in cell adhesion on FN in comparison to β1 wt in short term adhesion assays (30 min). The adhesive response of the β1-deficient cells to FN was much more susceptible to inhibition by RGD peptide than that of cells expressing β1 integrin (Fig. 4, A and B). The β1-deficient cells also failed to mediate RGD-independent cell adhesion on TG-FN, whereas the attachment and spreading was restored in β1 wt and β1 ab cells on TG-FN in the presence of RGD, strongly indicating that β1 integrin is required for the RGD-independent cell adhesion in response to TG-FN. To investigate a possible direct interaction between syndecan-4 and β1 integrins via the syndecan-4 core protein (38) during TG-FN mediated RGD-independent cell adhesion, we immunoprecipitated syndecan-4 in sdc-4 wt, ko, and ab cells seeded on the heparin-blocked TG-FN matrix in the presence of RGD. Immunoblot analysis of the precipitates with anti-β1 integrin antibody revealed that syndecan-4 did not interact with integrin β1 (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Importance of β1 integrin function in the support of the RGD-independent cell adhesion. A and B, β1 integrin wild type (β1 wt) and knock out (β1 ko) fibroblasts and β1 integrinko fibroblasts stably transfected with human β1 integrin cDNA (β1 ab) or mock vector (β1vec) were pretreated with RAD or RGD peptide (100 μg/ml) and seeded on FN and TG-FN matrices. Cell adhesion is expressed as the mean percentage of attachment and spreading of β1 wt cells on the FN matrix (in the presence of RAD) ± S.D., which represents 100% and signifies the mean of at least three experiments performed in triplicate. Total number of cells analyzed in control samples was ∼450. Bar, 20 μm. C, lysates of syndecan-4 wild type (sdc4 wt) and knock out (sdc4 ko) fibroblasts and syndecan-4 ko fibroblasts stably transfected with human syndecan-4 cDNA (sdc4 ab) were immunoprecipitated with anti-syndecan-4 and Western-blotted for β1 integrin (130 kDa). The first lane shows the β1 integrin control (β1 control). D, Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts were treated with 100 μg/ml RAD or RGD peptide and seeded on bovine serum albumin (BSA), FN, and TG-FN matrices. Lysates of cells samples were Western-blotted and probed with FAK antibodies (125 kDa) for tyrosine phosphorylation at 397 and 861 and ERK1 (44 kDa) and ERK2 (42 kDa) antibody for phosphorylation at tyrosine 204. Equal loading was ensured by probing the blots with anti-α-tubulin antibody.

Cell-ECM adhesion mediated by syndecan-4 and β1 integrins generates intracellular signals stimulating a number of non-receptor tyrosine kinases (34), notably FAK, followed by the activation of the MEK (mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase)/ERK cascade. FAK activation by adhesion receptors involves phosphorylation of up to six different tyrosine residues (39). Initial activation involves FAK autophosphorylation at Tyr397, which was shown to take place during RGD-independent cell adhesion to TG-FN in human osteoblasts (19). We, therefore, analyzed the autophosphorylation of FAK (Tyr397) along with tyrosine phosphorylation at 861 (Tyr861) in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts (Fig. 4C). Phosphorylation at Tyr397 and Tyr861 in FAK was markedly reduced when cells were seeded on bovine serum albumin or on FN in the presence of RGD. However, phosphorylation of both residues in response to TG-FN was increased to a level comparable with control cells on FN. Western blots performed in parallel showed no significant change in the total FAK levels in the same protein extracts. Because FAK phosphorylation at Tyr861 is induced by integrin clustering and does not require integrin-ligand engagement (40), these data suggests that RGD-independent adhesion via TG-FN promotes FAK phosphorylation due to up-regulation of both cell-matrix interactions and integrin clustering through inside-out signaling.

Anchorage-dependent activation of FAK is followed by the activation of ERK. We, therefore, monitored ERK1/2 activity in TG-FN induced RGD-independent cell adhesion using phospho-specific ERK1/2 antibodies (Fig. 4C). Western blot analysis revealed that loss of cell adhesion on bovine serum albumin or on FN matrix with RGD led to 2-fold reduction in tyrosine phosphorylation levels of ERK1 and ERK2 (p-ERK1/2), in comparison to the levels recorded for cells on FN. However, a robust increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation was observed in cells plated on TG-FN in the presence of RGD, suggesting that ERK1/2 activation is involved in adhesion signals that are transduced by TG-FN in an RGD-independent manner.

Loss of Raf-1 Impairs the Restoration of Cell Adhesion by TG-FN— The fundamental role of RhoA in TG-FN-driven RGD-independent cell adhesion was illustrated by failure in assembly of actin stress fibers after C3 exotransferase treatment (19). Recent evidence supports a link between Rho regulation and Raf-1 kinase in cell adhesion signaling during wound healing, as Raf-1-deficient fibroblasts demonstrate a defect in actin cytoskeleton organization on FN (25). We performed cell adhesion assays using Raf-1 deficient (Raf-1 ko) and wild-type (Raf-1 wt) fibroblasts to determine the role of Raf-1 in RGD-independent cell adhesion in response to TG-FN. Once attached and spread on FN and/or TG-FN, Raf-1 wt cells displayed a Swiss 3T3 fibroblast-like appearance. However, Raf-1 ko cells demonstrated a non-homogenous morphology with flattened spindle-like cells and cuboidal cells (Fig. 5B) (25). Moreover, Raf-1 ko cells attached and spread ∼56% less on FN compared with wt cells (Fig. 5A). The treatment of Raf-1 wt and ko cells with 100 μg/ml RGD peptide resulted in a 60% decrease in attachment and a 50% decrease in spreading on FN matrices. When RGD-independent cell adhesion was analyzed on TG-FN, Raf-1 wt cells were able to restore their attachment and spreading nearly to control levels, whereas Raf-1 ko cells displayed no significant (p > 0.05) increase in cell adhesion, indicating that Raf-1 is necessary for the rescue of RGD-independent cell adhesion by the TG-FN complex. Next, we investigated whether the kinase activity of Raf-1 was necessary for its function in the RGD-independent pathway using stable Raf-1 ko fibroblasts cell lines which express full-length kinase-competent Raf-1 (KC3 cells) and the kinase-dead domain of Raf-1 (KD4 cells) along with V8 cells that are transfected with the empty vector. Re-expression of the full-length Raf-1 and kinase-dead domain of Raf-1 in Raf-1 ko cells restored both the cell morphology (Fig. 5B) and the level of cell adhesion (Fig. 5A). V8 cells showed no morphological difference to Raf-1 ko cells and displayed comparable cell adhesion pattern. RGD peptide reduced the cell attachment and spreading of KC3 and KD4 cells on FN to levels similar to those recorded for the wild type fibroblasts. The RGD-impaired cell adhesion was restored on TG-FN in KC3 and KD4 cells, indicating that the physical presence of Raf-1, but not its kinase activity, is required in TG-FN-mediated cell adhesion.

FIGURE 5.

Adhesion of Raf-1 wt and Raf-1 ko fibroblasts to FN and TG-FN matrices in the presence of RAD and RGD peptides. A and B, Raf-1 wild type (Raf-1 wt) and knock out (Raf-1 ko) 3T3-like immortalized fibroblast cell lines and stable clones of Raf-1 ko cells expressing either full-length kinase-competent of Raf-1 (KC3) or a kinase-dead domain of Raf-1 protein (KD4) as well as empty vector (V8) were pretreated with RAD and RGD peptide (100 μg/ml) and allowed to attached on FN and TG-FN matrices. Data represents the means percentage attachment and spreading ±S.D. of triplicate wells from four experiments. The total number of cells analyzed for the control sample was ∼400. The ordinates of the graphs represent the mean cell attachment and spreading expressed as mean percentage of control attachment of Raf-1 wt fibroblasts on FN ± S.D., which represents 100%. Bar, 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

In our previous paper we demonstrated that when cells such as fibroblasts, osteoblasts, and endothelial-like cells were plated on a TG-FN complex they were capable of mediating an RGD-independent cell adhesion process via cell surface HSPGs, since digestion of cell surface HS chains inhibited the RGD-independent cell attachment and spreading on TG-FN (19). Our initial objective in this paper was, therefore, to identify the HSPG involved in this interaction with TG-FN and to determine whether this interaction is mediated directly via binding of the HSPG to TG2 as TG2 is known to have a high affinity for heparin (15). First we show that CHO-K1 cells deficient in synthesis of HS chains did not attach or spread on TG-FN in an RGD-independent manner, confirming the importance of HS chains in this process. To indicate that the interaction with the cell surface HS chains was via TG2 rather than FN, we demonstrate that saturation of the heparan sulfate binding sites on the FN matrix with the heparan sulfate analogue heparin before TG2 immobilization did not inhibit the RGD-independent adhesion of Swiss 3T3 cells to this matrix. Hence, during RGD-independent cell adhesion, association of FN-bound TG2 with HS chains could be the sole receptor ligand interaction However, we cannot rule out that the binding of FN-bound TG2 to the HS chains could also reinforce/expose cryptic sites on FN that are recognized by other unknown receptors or by the syndecan-4 core domain (38), leading to the stabilization of the TG-FN interaction with HSPGs.

Among the heparan sulfate proteoglycans, syndecan-4 is the most ubiquitous (11) and has been found in focal contacts acting in cooperation with integrins in a Rho and PKCα-dependent manner (41). Using sdc-4 ko, wt, and sdc-4 add-back fibroblasts in syndecan-4 immunoprecipitation studies, we demonstrate that FN-bound TG2 is directly associated with syndecan-4. Importantly we also show that deletion of syndecan-4 in fibroblasts abrogated the RGD-independent cell adhesion and actin stress fiber formation on the TG-FN matrix. This could be restored when syndecan-4 was transfected back into these cells, indicating that syndecan-4 is the HSPG responsible for binding the TG-FN complex when α5β1 integrins are blocked with RGD peptide. Finally, in agreement with the results obtained from CHO-K1 mutant cells, heparitinase treatment of sdc-4 wt cells produced a morphology similar to that of sdc-4 ko cells and blocked the response to the TG-FN matrix (data not shown). These results confirm that syndecan-4 is the primary receptor that TG2 binds to when complexed with FN and that this interaction is with the HS chains rather than the core protein of syndecan-4.

Having shown that TG2 associates with syndecan-4, we next investigated the downstream signaling pathway to gain a mechanistic insight into RGD-independent cell adhesion. We demonstrate that PKCα and -β1 integrin activation are both important in the TG-FN-mediated RGD-independent pathway. First, the inhibition of cell adhesion by the RGD peptide and treatment of cells with the PKCα inhibitor Go6976 led to a substantial decrease in the membrane levels of PKCα accompanied by diminished RGD-independent cell adhesion on TG-FN. Second, syndecan-4 ko cells transfected back with PKCα-binding mutant syndecan-4 cDNA were unable to support RGD-independent cell adhesion. Third, treatment of fibroblasts with the GK-21 inhibitory peptide that is known to block the association between PKCα and β1 integrin cytoplasmic domain (35) reduced the RGD-independent cell adhesion and associated stress fiber formation. Finally, β1 integrin null fibroblasts, although expressing other TG2-associating integrins (β3 and β5), could not to respond to the TG-FN matrix. Taken together, these data indicate that syndecan-4-driven stimulation of PKCα and subsequent association and activation of β1 integrins is necessary for cell adhesion and formation of actin bundling in cells that adhere on TG-FN in the presence of RGD.

The TG-FN-mediated RGD-independent cell adhesion via syndecan-4 differs from the classical cell adhesion to FN, where formation of focal adhesions and actin stress fibers is integrin-initiated but syndecan-4-dependent. In RGD-independent cell adhesion, syndecan-4 acts as the primary receptor, and its physical interaction with FN-bound TG2 but not with β1 integrin leads to PKCα-induced β1 integrin activation, which is in turn necessary for actin stress fiber organization. A comparable novel adhesion pathway has been recently reported in which the cysteine-rich domain of the disintegrin ADAM 12 can support cell adhesion and actin stress fiber formation through syndecan-4-driven PKCα signaling in a β1 integrin-dependent manner (42). However, the RGD-independent cell adhesion pathway demonstrated TG2 binding to syndecan-4 is different from that mediated by ADAM 12 in that, unlike the ADAM 12 mechanism, it does not require additional outside in activation of β1 integrins with activating antibodies. In the case of TG-FN-mediated signaling via syndecan-4, the process itself can activate β1 integrins by prompting intracellular cross-talk between syndecan-4 and β1 integrin, resulting in cell spreading.

The architecture of the actin cytoskeleton depends on the activation status of the Rho GTPase family members, mainly RhoA. The introduction of RhoA inhibitor C3 exotransferase was demonstrated previously to abolish RGD-independent actin cytoskeleton organization and focal adhesion formation, indicating that our model pathway relies on regulation of RhoA (19). We, therefore, propose that in RGD-impaired cell adhesion, FN-bound TG2 engagement by syndecan-4 causes PKCα-driven modulation of RhoA and stress fiber bundling in a β1 integrin-dependent manner. This mechanistic model agrees with the data of Dovas et al. (43) who suggested a linear pathway, whereby signaling though syndecan-4, PKCα, and RhoA is required for the formation and maintenance of actin stress fibers in fibroblasts. RhoA cooperates with downstream effectors Rok-α and mDIA to promote the formation of actin stress fibers. It is now recognized that Rok-α associates with c-Raf-1 kinase and regulates RhoA-mediated signaling in fibroblasts (25). The mechanism of Raf-1 regulated Rho signaling is yet to be determined, but our data indicate Raf-1 to be important in the RGD-independent cell adhesion pathway since the Raf-1 ko fibroblasts do not support TG-FN mediated RGD-independent cell adhesion unless transfected with full-length or kinase-inactive domain Raf-1. We, therefore, anticipate that the Raf-1 protein is essential for the signaling pathway mediated by TG-FN and regulates this pathway in a Rho-dependent manner via a protein-protein interaction.

Combinatory signaling from syndecans and integrins after attachment to FN is essential for the appropriate organization of the actin cytoskeleton and subsequent activation of the MAPKs such as FAK (34, 41). Engagement of syndecan-4 with FN-bound TG2 can form matrix attachments that generate cross-talk between syndecans and integrins resulting in integrin clustering through inside-out signaling. In support of this model, our data showed that RGD-independent cell adhesion to FN-bound TG2 promotes β1 integrin accumulation in focal structures (data not shown) and phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr397 and at Tyr861, which occurs in the event of ligand-independent integrin clustering (40). Once activated, FAK can stimulate ERK, which is linked to survival signaling. Given that the TG-FN complex can rescue primary dermal fibroblasts from anoikis with the maintenance of cell viability (19), it is not surprising that the phosphorylation levels of the survival kinase ERK1/2 were induced almost back to normal levels, and inhibition of ERK1/2 abolished RGD-independent cell adhesion in response to TG-FN (data not shown).

An increasing number of reports now confirm the importance of TG2 in tissue injury and wound repair (44–46). RGD-independent cell adhesion mediated by matrix-bound TG2-syndecan-4 interactions could be physiologically relevant in tissue remodeling during differentiation and/or after wounding (7, 47). Both these events are known to cause up-regulation and secretion of TG2 (44, 48) and involve remodeling of the matrix by numerous proteases. This in turn leads to the subsequent generation of soluble RGD-containing peptides (20), which have the potential to compete and disrupt cell/matrix binding sites leading to loss of cell adhesion and anoikis. Important to our hypothesis is the observation that interaction of TG with either FN or heparin leads to the increased resistance of TG2 to proteolysis (49, 50). Therefore, in situations of matrix breakdown during tissue remodeling, a protease-resistant complex rich in FN-bound TG2 could interact with syndecan-4 to reinforce or substitute for RGD-dependent cell adhesion, thus further extending the role of this multifunctional enzyme in tissue repair. In conclusion, our results shown in this paper allow us to propose a novel RGD-independent cell adhesion and cell survival process in which binding of syndecan-4 to FN-bound TG2 activates PKCα, facilitating its association with β1 integrins, leading to reinforcement of actin-stress fiber formation and MAPK pathway activation (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Summary of proposed TG-FN mediated RGD-independent cell adhesion pathway. After tissue damage and/or remodeling, degradation of the ECM leads to formation of RGD-containing FN fragments which can compete for the RGD-dependent cell binding sites ultimately leading to loss of cell adhesion and anoikis. FN-bound TG2 (TG-FN heterotropic complex) with increased resilience to MMP degradation (49) maintains cell adhesion by interacting with cell surface heparan sulfate chains of syndecan-4. Engagement of syndecan-4 with TG-FN matrix complex initiates the cascade of signaling events leading to inside-out activation of integrins, focal adhesion formation, and actin cytoskeleton reorganization and the activation of survival kinase pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Russell Collighan for critically reading this manuscript and Elif Damla Arisan for technical support.

This work was supported in part by Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey SBAG Grant 104S606. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table 1 and Figs. 1–3.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: TG2, tissue transglutaminase; PKCα, protein kinase Cα; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; wt, wild type; ko, knock out; CP, control peptide; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; ECM, extracellular matrix; FN, fibronectin; HSPG, heparan sulfate proteoglycan; Chinese hamster ovary; sdc4, syndecan-4.

References

- 1.Griffin, M., Casadio, R., and Bergamini, C. M. (2002) Biochem. J. 368 377-396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harsfalvi, J., Arato, G., and Fesus, L. (1987) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 923 42-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piacentini, M., Amendola, A., Ciccosanti, F., Falasca, L., Farrace, M. G., Mastroberardino, P. G., Nardacci, R., Oliverio, S., Piredda, L., Rodolfo, C., and Autuori, F. (2005) Prog. Exp. Tumor Res. 38 58-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balklava, Z., Verderio, E., Collighan, R., Gross, S., Adams, J., and Griffin, M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 16567-16575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaudry, C. A., Verderio, E., Aeschlimann, D., Cox, A., Smith, C., and Griffin, M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 30707-30714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akimov, S. S., Krylov, D., Fleischman, L. F., and Belkin, A. M. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 148 825-838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Telci, D., and Griffin, M. (2006) Front. Biosci. 11 867-882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skill, N. J., Johnson, T. S., Coutts, I. G., Saint, R. E., Fisher, M., Huang, L., El Nahas, A. M., Collighan, R. J., and Griffin, M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 47754-47762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verderio, E. A. M., Johnson, T., and Griffin, M. (2004) Amino Acids 26 387-404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humphries, M. J., Travis, M. A., Clark, K., and Mould, A. P. (2004) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32 822-825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couchman, J. R., Chen, L., and Woods, A. (2001) Int. Rev. Cytol. 207 113-150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woods, A., Couchman, J. R., Johansson, S., and Hook, M. (1986) EMBO J. 5 665-670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloom, L., Ingham, K. C., and Hynes, R. O. (1999) Mol. Biol. Cell 10 1521-1536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bass, M. D., and Humphries, M. J. (2002) Biochem. J. 368 1-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chau, D. Y. S., Collighan, R. J., Verderio, E. A. M., Addy, V. L., and Griffin, M. (2005) Biomaterials, 26 6518-6529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aeschlimann, D., and Paulsson, M. (1994) Thromb. Haemostasis 71 402-415 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi, H., Isobe, T., Horibe, S., Takagi, J., Yokosaki, Y., Sheppard, D., and Saito, Y. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 23589-23595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson, T. S., El-Koraie, A. F., Skill, N. J., Baddour, N. M., El Nahas, A. M., Njloma, M., Adam, A. G., and Griffin, M. (2003) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14 2052-2062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verderio, E. A. M., Telci, D., Okoye, A., Melino, G., and Griffin, M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 42604-42614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Midwood, K. S., Williams, L. V., and Schwarzbauer, J. E. (2004) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 36 1031-1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leblanc, A., Day, N., Menard, A., and Keillor, J. W. (1999) Protein Expression Purif. 17 89-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freund, K. F., Doshi, K. P., Gaul, S. L., Claremon, D. A., Remy, D. C., Baldwin, J. J., Pitzenberger, S. M., and Stern, A. M. (1994) Biochemistry 33 10109-10119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verderio, E., Nicholas, B., Gross, S., and Griffin, M. (1998) Exp. Cell Res. 239 119-138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bass, M. D., Roach, K. A., Morgan, M. R., Mostafavi-Pour, Z., Schoen, T., Muramatsu, T., Mayer, U., Ballestrem, C., Spatz, J. P., and Humphries, M. J. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 177 527-538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ehrenreiter, K., Piazzolla, D., Velamoor, V., Sobczak, I., Small, J. V., Takeda, J., Leung, T., and Baccarini, M. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 168 955-964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mostafavi-Pour, Z., Askari, J. A., Whittard, J. D., and Humphries, M. J. (2001) Matrix Biol. 20 63-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreuger, J., Spillmann, D., Li, J. P., and Lindahl, U. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 174 323-327 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McFall, A. J., and Rapraeger, A. C. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 12901-12904 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McFall, A. J., and Rapraeger, A. C. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 28270-28276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woods, A., Longley, R. L., Tumova, S., and Couchman, J. R. (2000) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 374 66-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim, S. T., Longley, R. L., Couchman, J. R., and Woods, A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 13795-13802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mostafavi-Pour, Z., Askari, J. A., Parkinson, S. J., Parker, P. J., Ng, T. T., and Humphries, M. J. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 161 155-167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ng, T., Parsons, M., Hughes, W. E., Monypenny, J., Zicha, D., Gautreau, A., Arpin, M., Gschmeissner, S., Verveer, P. J., Bastiaens, P. I., and Parker, P. J. (2001) EMBO J. 20 2723-2741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan, M. R., Humphries, M. J., and Bass, M. D. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8 957-969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parsons, M., Keppler, M. D., Kline, A., Messent, A., Humphries, M. J., Gilchrist, R., Hart, I. R., Quittau-Prevostel, C., Hughes, W. E., Parker, P. J., and Ng, T. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 5897-5911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fassler, R., and Meyer, M. (1995) Genes Dev. 9 1896-1908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fok, J. Y., Ekmekcioglu, S., and Mehta, K. (2006) Mol. Cancer Ther. 5 1493-1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saito, Y., Imazeki, H., Miura, S., Yoshimura, T., Okutsu, H., Harada, Y., Ohwaki, T., Nagao, O., Kamiya, S., Hayashi, R., Kodama, H., Handa, H., Yoshida, T., and Fukai, F. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 34929-34937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitra, S. K., Hanson, D. A., and Schlaepfer, D. D. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6 56-68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi, Q., and Boettiger, D. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell 14 4306-4315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilcox-Adelman, S. A., Denhez, F., and Goetinck, P. F. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 32970-32977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thodeti, C. K., Albrechtsen, R., Grauslund, M., Asmar, M., Larsson, C., Takada, Y., Mercurio, A. M., Couchman, J. R., and Wewer, U. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 9576-9584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dovas, A., Yoneda, A., and Couchman, J. R. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119 2837-2846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson, T. S., Skill, N. J., El Nahas, A. M., Oldroyd, S. D., Thomas, G. L., Douthwaite, J. A., Haylor, J. L., and Griffin, M. (1999) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10 2146-2157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Griffin, M., Smith, L. L., and Wynne, J. (1979) Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 60 653-661 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mirza, A., Liu, S. L., Frizell, E., Zhu, J., Maddukuri, S., Martinez, J., Davies, P., Schwarting, R., Norton, P., and Zern, M. A. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. 272 G281-G288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomazy, V. A., and Davies, P. J. (1999) Cell Death Differ. 6 146-154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haroon, Z. A., Hettasch, J. M., Lai, T. S., Dewhirst, M. W., and Greenberg, C. S. (1999) FASEB J. 13 1787-1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Belkin, A. M., Akimov, S. S., Zaritskaya, L. S., Ratnikov, B. I., Deryugina, E. I., and Strongin, A. Y. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 18415-18422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gambetti, S., Dondi, A., Cervellati, C., Squerzanti, M., Pansini, F. S., and Bergamini, C. M. (2005) Biochimie (Paris) 87 551-555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.