Abstract

Conjugation to SUMO is a reversible post-translational modification that regulates several transcription factors involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, and disease. The p53 tumor suppressor can be modified by SUMO-1 in mammalian cells, but the functional consequences of this modification are unclear. Here, we demonstrate that the Drosophila homolog of human p53 can be efficiently sumoylated in insect cells. We identify two lysine residues involved in SUMO attachment, one at the C terminus, between the DNA binding and oligomerization domains, and one at the N terminus of the protein. We find that sumoylation helps recruit Drosophila p53 to nuclear dot-like structures that can be marked by human PML and the Drosophila homologue of Daxx. We demonstrate that mutation of both sumoylation sites dramatically reduces the transcriptional activity of p53 and its ability to induce apoptosis in transgenic flies, providing in vivo evidence that sumoylation is critical for Drosophila p53 function.

The p53 tumor suppressor is a highly regulated transcription factor that coordinates cellular responses to DNA damage, activation of oncogenes, and a variety of other stress signals (1); accordingly, p53 inactivation is the most common mutation found in human cancers (2). A complex array of post-translational modifications regulates stability, localization, conformation, and transcriptional activity of p53, with crucial implications for its tumor suppressive function (3–6).

SUMO-1 belongs to a family of small ubiquitin-related proteins that are covalently linked to lysine residues of protein substrates (7, 8). In contrast to ubiquitination, sumoylation does not target modified proteins for degradation, but can affect their localization, stability, and functions (7–10). Human p53 can be modified by SUMO-1 on a single C-terminal lysine (Lys-386), but the effects of this modification are controversial (3, 11). Initial studies indicated that SUMO stimulates the activity of p53 (12–14). In contrast, other works suggested that sumoylation does not affect p53 transcriptional activity (15, 16). In addition, conflicting reports indicate that the SUMO E3 ligase PIAS1 can either stimulate or inhibit p53 activity (15, 17). Overexpression of SUMO-1 stimulates recruitment of p53 to Promyelocytic Leukemia Protein (PML)4 Nuclear Bodies (NBs), with implications for p53 pro-apoptotic activity, but mutation of the SUMO acceptor site does not prevent p53 localization to NBs (16, 18). Two knock-in mouse models have been generated in which all C-terminal lysine residues in p53 have been mutated, including the sumoylation site; despite extensive cell culture data indicating critical roles of these residues for p53 function, these mice are similar to wild type, and MEFs and thymocytes derived from these animals display normal apoptotic responses after DNA damage (19, 20). These results suggest that several post-translational modifications of the C terminus, including sumoylation, may not be crucial for p53 function in mammalian cells (5).

Other members of the p53 family are also sumoylated at their C terminus (3). In cell culture, sumoylation of p63α destabilizes the protein and decreases its transactivation function (21, 22) while sumoylation of p73α modulates its nuclear localization and turnover (23). Therefore, although the biological effects of sumoylation may vary among p53-related proteins, modification with SUMO is a common feature of the p53 family, suggesting an ancient regulatory mechanism inherited from a common ancestor gene.

In Drosophila melanogaster there is a single p53 family member, with the same domain structure of mammalian p53 proteins. The core DNA binding domain has the greatest sequence similarity, while the N- and C-terminal domains show little sequence conservation but retain similar structural and functional features (24–27). Drosophila p53 binds the same consensus sequence as human p53, and transactivates reporter constructs driven by p53 responsive elements (24–26). Drosophila mutants lacking p53 function are viable and fertile, but are defective for induction of apoptosis by DNA damage or unprotected telomeres (24, 26, 28–31). Drosophila p53 induces cell death when overexpressed in eye imaginal discs (24, 26), up-regulates pro-apoptotic genes including reaper, sickle, hid, and Eiger, and binds a specific DNA damage responsive element within the reaper promoter (28–30, 32). Activation of Drosophila p53-dependent apoptosis following DNA damage depends on the protein kinase Mnk/Chk2, which phosphorylates p53 (28, 33). Other post-translational modifications of Drosophila p53 have not been demonstrated.

Here we show that Drosophila p53 can be modified by SUMO on two independent residues. We present evidence that a sumoylation-defective p53 mutant is markedly less active than the wild-type counterpart, in cell culture and in vivo, implicating sumoylation in the biochemical circuitry that positively regulates Drosophila p53 function.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids—The cDNA for Drosophila p53 was picked from the Drosophila Gene Collection (DGC1.0). Mutants K26R, K302R, and KRKR were generated by PCR-based mutagenesis. The cDNAs for Drosophila SUMO and Daxx-like protein (DLP)(ct) were retrieved from DGC1.0, while full-length DLP was obtained from the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center (DGRC). Coding regions were amplified by PCR and inserted in pAc5.1 vectors (Invitrogen) modified for expression of N-terminally RGS-His-, HA-, or GFP-tagged proteins. In the SUMO-KRKR chimera, Drosophila SUMO (amino acids 1–85) is fused to residue 18 of the p53 KRKR mutant. Expression of the fusion protein at the expected molecular weight was verified by immunoblotting (not shown). For luciferase assays, untagged wild-type p53 and Lys to Arg mutants were cloned in pAc5.1 vectors. All constructs involving PCR were fully sequenced. pRpr150-LUC was constructed inserting the 150-bp EcoRI-XhoI fragment from the pH150-LacZ reporter (24) into the EcoRI-XhoI sites of the pGL2-promoter vector (Promega).

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Luciferase Assays—S2 cells were cultured at 26 °C in Schneider's Drosophila medium (Invitrogen) with 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum, penicillin (50 units/ml), and streptomycin (50 mg/ml). Transfections were performed by calcium phosphate co-precipitation. For luciferase assays, S2 cells in 3-cm Petri dishes were transfected with 500 ng of the reporter, and 250 ng or 500 ng of p53 expression plasmids. In all samples, 100 ng of pPacLacZ were included for normalization of transfection efficiency. After 36 h, cells were lysed and assayed for Luciferase and β-galactosidase activity. Fold induction is the ratio of luciferase over β-galactosidase, normalized to the activity of the reporter co-transfected with empty vector. Expression levels of transfected proteins were verified by immunoblotting of the same lysates; gel loading was normalized for transfection efficiency using β-galactosidase levels.

Western Blotting, Immunoprecipitation, and Immunofluorescence—Immunoblotting was performed under standard conditions. For immunoprecipitations, S2 cells seeded in 6-cm Petri dishes were collected 24 h after transfection and lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (300 mm NaCl) containing 10 mm N-ethylmaleimide, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and protease inhibitors. Clarified lysates were incubated at 4 °C with anti RGS-His primary antibody cross-linked to protein G-Sepharose (GE Healthcare). For immunofluorescence, 36 h after transfection S2 cells were plated on glass coverslips coated with 0.5 mg/ml concanavalin A (Sigma) or 0.5 mg/ml poly-lysine (Sigma). After 2 h, cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min. Cells were permeabilized in PBS plus 0.1% Triton X-100. Images were captured using a laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss Axiocam 100 m). The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-RGS-His (Qiagen), rabbit anti-GFP (self produced), rabbit anti-SUMO (34), mouse anti-HA (mAb 12CA5), mouse anti-Drosophila p53 (24).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay—For EMSA, ∼5 × 106 S2 cells seeded in 6-cm Petri dishes were transfected with p53 expression plasmids and harvested 48 h after transfection in lysis buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and protease inhibitors). After 20 min on ice, extracts were centrifuged at 16000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris. Protein concentration in supernatants was determined using Bio-Rad protein assay. Expression levels of transfected proteins were verified by immunoblotting of the same lysates. A 26-mer DNA oligonucleotide containing the cis-acting p53 responsive sequence from the Reaper enhancer (5′-ACCTGACATGTTTGAACAAGTCGAGC-3′) was end-labeled with 32P and annealed to the complementary strand. For binding reactions, 30 μg of whole cell extract were added to gel shift buffer (20 mm HEPES pH 8, 25 mm KCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol, 0.025% Nonidet P-40, 2 mm spermidine, 10% glycerol, 0.1 mg/ml acetylated bovine serum albumin, 120 ng of double-stranded poly(d[I-C])) containing the labeled oligonucleotide in a final volume of 30 μl. Competition was done adding 500 ng of unlabeled double-stranded oligonucleotide. Reactions were incubated for 30 min at room temperature, and electrophoresed on a non-denaturing 4% polyacrylamide gel before autoradiography.

Transgenes and Genetics—Flies were raised at 25 °C. Wild-type p53 and p53KRKR were expressed using the GUS vector, which contains both the UAS promoter for inducible expression by Gal4, and Glass binding sites from GMR for low to moderate expression in the developing eye (24, 28). Cloning of wild-type p53 was previously described (28), while GUSp53KRKR was constructed using Gateway cloning. For high levels of p53 expression, GMRGal4 animals were crossed to four independent lines of GUSp53+ and GUSp53KRKR. For lower levels of expression and rescue of damage-induced apoptosis, p53- animals were crossed to GUSp53+; p53-, and GUSp53KRKR; p53- flies.

Irradiation and Immunohistochemistry—Climbing third instar larvae were irradiated with 4000 rads using a faxitron x-ray cabinet or mock-treated. Four hours following irradiation, eye discs were dissected and stained with antibodies as previously described (24). Discs were incubated with primary antibodies in PBTN (PBS, 0.3% Triton, 5% normal goat serum) overnight at 4 °C, and with secondary antibodies in PBTN for 2 h at room temperature. The primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 (1:100, Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-SUMO (1:1000, gift from L. C. Griffith) (34), and mouse anti-Drosophila p53 (1:10) (24). The secondary antibodies used were donkey anti-mouse Alexa 488 and donkey anti-rabbit Alexa 555 (1:2000, Molecular Probes). TUNEL staining was performed using ApopTag Fluorescein In Situ Apoptosis Detection kit (Chemicon). Eye imaginal discs were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, washed five times with PBTw (PBS + 0.3% Tween-20), and postfixed with cold ethanol/PBS (2:1). Following rehydration and washing, discs were treated with TdT mix for 1 h at 37 °C. After the reaction was stopped, discs were incubated with fluorescein-conjugated anti-dig antibody for 30 min and mounted with Vectashield.

Confocal Microscopy and Quantification of TUNEL and Active Caspase Staining—Localization of p53 and SUMO was visualized using a Leica SP2 AOBS confocal microscope with a ×63 objective. For an overall view of the GMR region, a Z-series was taken through the eye disc at intervals of 284 nm, at a zoom of 1.75. For a higher magnification view, a Z-series was taken through the eye disc at intervals of 122 nm, at zoom of 4. To quantify the amount of cleaved caspase-3 in the eye disc, a Z-series was taken through the entire eye disc at intervals of 1.42 μm with a ×20 objective. A three-dimensional reconstruction of each eye disc was generated using Imaris 5.0 image analysis software (Bitplane AG). Only the posterior region of the eye disc in which the p53 transgene is expressed was analyzed. The volume positive for cleaved caspase-3 was determined using a high intensity threshold, while the total disc volume was determined using a low intensity threshold (supplemental Fig. S4). The caspase-positive index for the posterior of the eye disc was calculated by dividing the cleaved caspase-3 volume by the total volume. To quantify the number and location of TUNEL-positive cells in the eye disc, a Z-series was taken through the entire eye using a Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope and an Hamamatsu ORCA-ER camera with a ×20 objective. Images were deconvolved using an inverse filter algorithm in the Zeiss Axiovision 4.5 image analysis software. Imaris 5.0 image analysis software was used to create a three-dimensional reconstruction of the TUNEL staining in the eye disc. Individual positive cells were marked using the “spot” function, which identifies local maxima of signal intensity (supplemental Fig. S4). The distance of TUNEL-positive cells from the morphogenetic furrow was determined by subtracting the position of the furrow from the position of each cell.

RESULTS

Identification of Two Functional Sumoylation Sites in Drosophila p53—In yeast two-hybrid screens, we and others have found interactions between Drosophila p53 and lesswright/dUbc9 (an E2 SUMO ligase), Su(var)2–10/dPIAS (an E3 SUMO ligase), and Ulp1 (a SUMO-specific peptidase), suggesting that p53 may be sumoylated (35, 36).5 Within the p53 sequence, there are two consensus sites for sumoylation, one on lysine 302 in the C-terminal region of the protein, the other on lysine 26 within the N-terminal transactivation domain (Fig. 1A). These sites do not directly correspond to the single site identified at the extreme C terminus of mammalian p53, p63, or p73 (3).

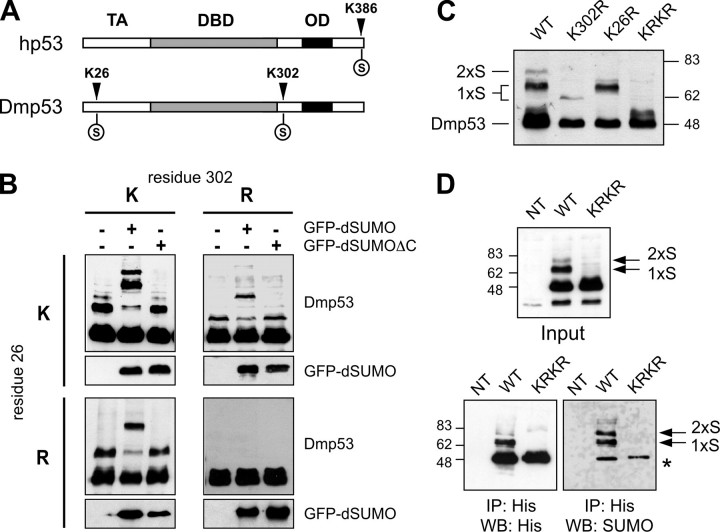

FIGURE 1.

Identification of two sumoylation sites in Drosophila p53. A, schematic structure of human and Drosophila p53, with respective sumoylation sites. The transactivation (TA), DNA binding (DBD), and oligomerization (OD) domains are indicated. B, sumoylation of p53. Wild-type HT-Dmp53 and the indicated mutants were transfected in S2 cells with or without plasmids expressing GFP-dSUMO or its non-conjugatable version GFP-dSUMOΔC. Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE. HT-Dmp53 and GFP-dSUMO were detected by immunoblotting. C, various sumoylated forms migrate differently. The indicated p53 mutants were transfected in S2 cells and analyzed by immunoblotting in the same gel. D, p53 is conjugated to endogenous SUMO. Wild-type HT-Dmp53 and the double-lysine KRKR mutant were transfected in S2 cells. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with a monoclonal antibody to the RGS-His tag, and revealed with an antibody to Drosophila SUMO (bottom right). Expression of HT-Dmp53 proteins was also analyzed in the immunoprecipitate (bottom left) and in total lysates (input). The antibody to Drosophila SUMO has a weak cross-reactivity to p53 (asterisk). Arrows indicate p53 modified with one or two SUMO molecules.

To test whether Drosophila p53 can be sumoylated, Drosophila S2 cells were transfected with His-tagged p53 (HT-Dmp53) alone, with Drosophila SUMO fused with GFP (GFP-dSUMO), or with a non-conjugatable version of SUMO lacking the C-terminal glycines necessary for attachment to substrates (GFP-dSUMOΔC). Transfected p53 was visualized by immunoblotting with an antibody to the RGS-His tag. As shown in Fig. 1, B and C, transfected p53 migrates as one primary band and two slower migrating bands; the apparent molecular weights are compatible with attachment of one or two SUMO molecules. In cells transfected with GFP-dSUMO, the upper bands shift to higher molecular weights, compatible with covalent attachment of one and two GFP-dSUMO molecules. This shift is not observed in cells transfected with the non-conjugatable GFP-dSUMOΔC (Fig. 1B).

To test the requirement of lysine 302 and lysine 26 for conjugation, they were replaced with arginine by site-directed mutagenesis. When either lysine 26 or lysine 302 are altered, the resulting proteins (p53 K26R and p53 K302R) display a single slower migrating band (Fig. 1B). When both residues are mutated, the resulting protein (p53 KRKR) is no longer modified. Comparison of the various mutants suggests that lysine 302 may be sumoylated more efficiently than lysine 26. In addition, modification at Lys-302 apparently induces a greater shift in migration than modification at Lys-26 (Fig. 1C).

To verify that endogenous SUMO is covalently attached to p53, HT-Dmp53 was immunoprecipitated from transfected S2 cells and probed with an antibody to Drosophila SUMO (Fig. 1D). Based on these results, we conclude that a significant fraction of Dmp53 is sumoylated when expressed in S2 cells, with lysine 302 being the primary modification site.

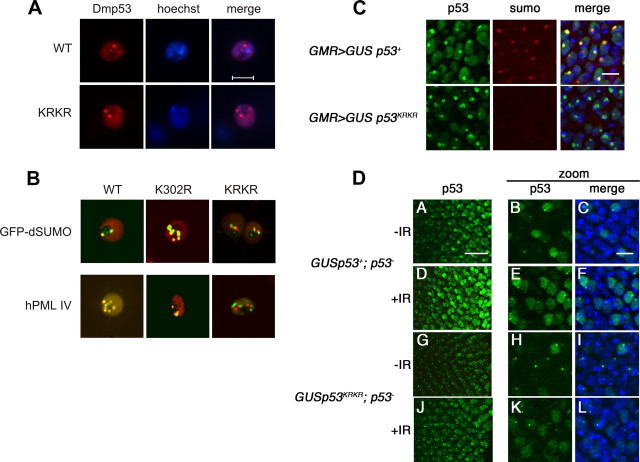

Drosophila p53 Localizes to Nuclear Dots—The distribution of wild-type and nonsumoylatable p53 was analyzed in transfected S2 cells. As shown in Fig. 2A, transfected p53 is found throughout the nucleus with marked accumulation in dot-like structures. p53 forms nuclear dots in 70–80% of transfected cells, with most nuclei having 2 or 3 dots. This localization was not dependent on the adhesion substrate (concanavalin A or polylysine) and did not change using N-terminally tagged or untagged p53 (not shown). The p53 Lys to Arg mutants form nuclear dots with similar frequency, shape, and size as the wild-type protein. When co-transfected with GFP-dSUMO, wild-type p53 and single lysine mutants co-localize with SUMO in nuclear dots. However, only a subset of nuclear dots formed by the nonsumoylatable p53 KRKR mutant overlap with dots formed by GFP-dSUMO (Fig. 2 and supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 2.

Nuclear localization of exogenous p53 in tissue culture and developing eye imaginal discs. A, wild-type and non sumoylatable p53 form nuclear dots in cultured cells. S2 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs, plated on concanavalin A-coated coverslips before fixation, and analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence using a monoclonal anti-Dmp53 antibody. Nuclei were visualized by Hoechst staining (scale bar, 5 mm). B, p53 sumoylation mutants display differential localization with respect to GFP-dSUMO and human PML IV. Wild-type p53 and the indicated mutants were co-transfected with GFP-dSUMO or human PML IV in S2 cells. Cells were treated as above. Localization of p53 proteins (red) and GFP-dSUMO or PML IV (green) was analyzed by confocal microscopy. Only merged images are shown, where yellow indicates co-localization. The complete set of single images for all the mutants are available as supplemental Figs. S1 and S2. C, Drosophila p53 (green), SUMO (red), and DAPI (blue) expression in the developing eye imaginal disc. High levels of p53 expression in the posterior of the developing eye imaginal disc were obtained using GMR-Gal4 to drive expression of GUSp53 transgenes. Overexpressed wild-type p53 accumulates endogenous SUMO in subnuclear domains. Overexpressed p53KRKR also forms nuclear dots, but recruits much less SUMO (scale bar, 5 μm). D, Drosophila p53 (green) and DAPI (blue) expression in irradiated developing eye imaginal discs. Overview (A) and high magnification (B and C) of moderately expressed wild-type p53, forming nuclear dots in an untreated eye disc. Overview (D) and high magnification (E and F) of wild-type p53 4 h after X-irradiation. Overview (G) and high magnification (H and I) of p53KRKR forming dots in an untreated eye disc. Overview (J) and high magnification (K and L) of p53KRKR 4 h after X-irradiation.

Localization of wild-type and nonsumoylatable p53 was also analyzed in transgenic flies, using the GAL4/UAS system. With a GMR-GAL4 driver, high levels of p53 are produced in the posterior of the developing eye imaginal disc, sufficient to induce ectopic apoptosis in the absence of DNA damage (24, 26, 28). In the absence of GAL4 driver, p53 is expressed at low levels, insufficient to induce apoptosis (see Fig. 5). Under both conditions, wild-type p53 and p53 KRKR are found throughout the nucleus with a subnuclear domain of elevated staining, similar to that seen in cell culture (Fig. 2, C and D). We used a polyclonal antibody to visualize endogenous SUMO in these cells (34). Endogenous SUMO is not detected in cells expressing less p53, probably because of low levels of SUMO throughout the entire nucleoplasm. At the higher p53 expression levels, endogenous SUMO accumulates in nuclear dots with wild type, but not with nonsumoylatable p53 (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 5.

p53KRKR does not induce apoptosis as efficiently as wild-type p53, and is unable to fully rescue DNA damage-induced apoptosis. A–F, high levels of p53 expression in the posterior of the developing eye imaginal disc were obtained using GMR-Gal4 to drive expression of GUSp53 transgenes. A, wild-type adult eye. B, adult eye overexpressing wild-type p53. C, adult eye overexpressing p53KRKR. D–F, TUNEL staining for apoptotic cells in eye imaginal discs. D, wild-type eye imaginal disc. E, eye disc overexpressing wild-type p53. F, eye disc overexpressing p53KRKR. Scale bar: 20 μm. G, distribution profiles of the distance of TUNEL-positive cells from the furrow in p53+-expressing cells versus p53KRKR-expressing cells. All samples were normalized to calculate the mean percentage of apoptotic cells at a given distance from the furrow out of the total number of apoptotic cells in the disc. Distribution profiles were generated to plot percent of apoptotic cells at each distance from the furrow (n = 5). H–O, cleaved caspase-3 staining of eye imaginal discs mock-treated, or 4 h after X-irradiation. In the absence of a Gal4 driver, the Glass/multimer promoter of GUSp53 transgenes expresses levels of p53 that can rescue DNA damage-induced apoptosis in a p53 mutant tissue, but are too low to induce apoptosis without an external stress. The transgene expression domain in the posterior of each eye disc is indicated with brackets. H–K, untreated eye discs. L–O, eye discs stained for cleaved capase-3 4 h after X-irradiation. P, quantification of relative volumes of cleaved caspase-3 staining in the regions marked by brackets. See “Experimental Procedures” for details of caspase quantification. Bars indicate S.E. (n = 5). A two-tailed Student's t test was used to determine the significance of the observed changes.

In contrast with cell culture results, p53 KRKR transgenic cells displayed lower overall levels of immunostaining, suggesting reduced expression levels. This result was observed in four independent transformants per line (data not shown), and therefore is not a consequence of genomic insertion sites. No p53 immunostaining was detected in cells solely expressing endogenous levels of p53 (data not shown). Following exposure to ionizing radiation (IR), wild-type p53, and p53 KRKR are still detected throughout the nucleus and in nuclear dots (Fig. 2D). Together, these results confirm that p53 accumulates in subnuclear structures in cultured cells and in normal developing tissues. The nonsumoylatable p53 KRKR mutant can also form nuclear dot-like structures, but has reduced capacity to recruit SUMO.

Sumoylation Affects p53 Localization to Nuclear Dots Defined by Human PML and Drosophila Daxx-like Protein—We next asked if nuclear dots formed by wild-type or nonsumoylatable p53 are in fact the same structures. In mammalian cells, p53 accumulates within PML NBs under specific conditions (16, 18, 37, 38). Markers for such structures are PML and Sp100 (39, 40), but there are no Drosophila homologs of these proteins. However, transfected human PML IV forms nuclear dots that co-localize with SUMO in Drosophila cells (41). When co-transfected with hPML IV, wild-type p53 and single lysine mutants co-localize with PML in nuclear dots. On the contrary, only a subset of nuclear dots formed by the nonsumoylatable p53 KRKR mutant overlap with those formed by PML (Fig. 2 and supplemental Fig. S2).

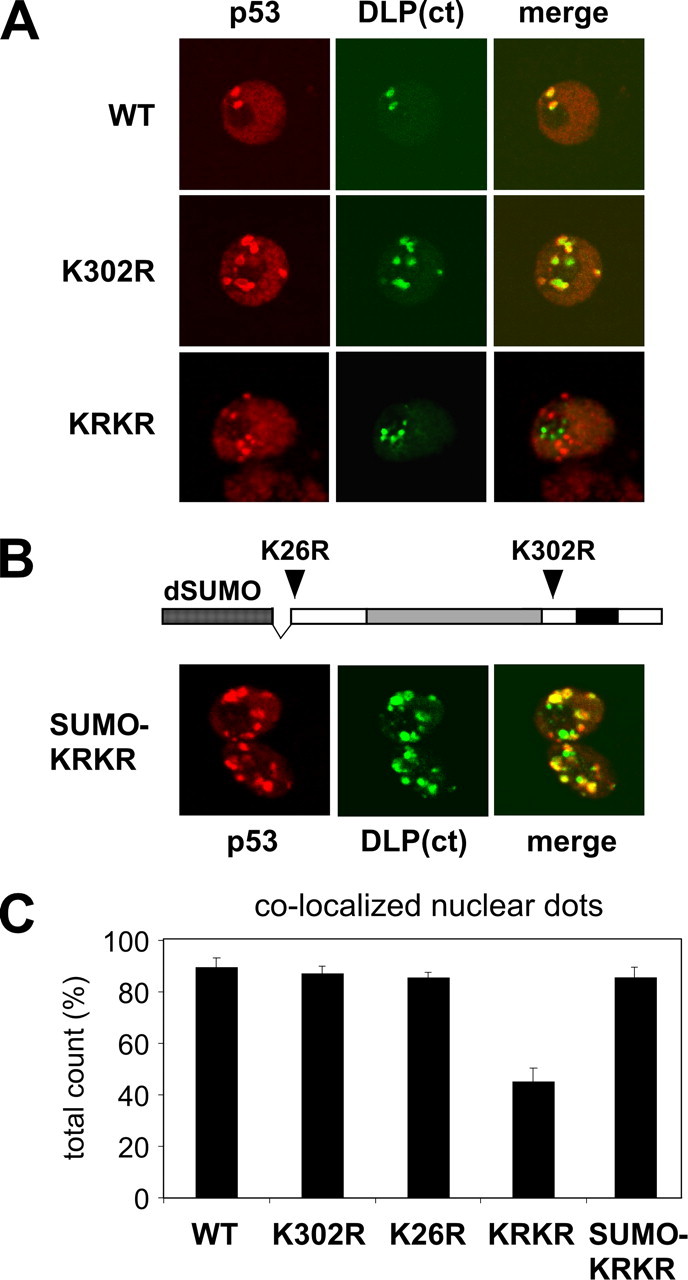

Daxx, a transcriptional repressor and scaffolding protein, is also found in mammalian PML-NBs (42, 43). The Drosophila homolog of Daxx, referred to as DLP, has been described very recently (44): it encodes a large peptide with similarity to Daxx in the C terminus. We observed that DLP accumulates in nuclear dots when overexpressed in Drosophila S2 cells, and these dots co-localize with GFP-dSUMO and human PML IV (supplemental Fig. S3). A DLP deletion lacking the first 710 amino acids, named DLP(ct), shows similar behavior, indicating that the region of Daxx similarity is sufficient for the observed localization (supplemental Fig. S3). We used GFP-DLP(ct) as a marker to analyze localization of p53 mutants; we counted the fraction of p53 nuclear dots co-localized with DLP(ct) in confocal images from independent co-transfection experiments (Fig. 3A). As summarized in Fig. 3C, 85–90% of the dots formed by wild-type p53 or single lysine mutants co-localize with DLP(ct). In contrast, only 45% of nuclear dots formed by the non-sumoylatable p53 KRKR co-localize with DLP(ct). Notably, the co-localization of the p53 KRKR mutant with DLP is restored to wild-type levels when SUMO is fused to p53 KRKR to mimic constitutive K26 sumoylation (Fig. 3B). Together, these results indicate that sumoylation affects the recruitment of Drosophila p53 to specific nuclear domains.

FIGURE 3.

Sumoylation affects localization of p53 to nuclear dots marked by DLP. A, mutation of the lysines affects p53 co-localization with DLP. Confocal analysis of the nuclear localization of wild-type p53 and lysine mutants with respect to GFP-DLP(ct) in transfected S2 cells. B, fusion to SUMO induces full co-localization of p53 KRKR with DLP. Confocal analysis of the nuclear localization of the SUMO-KRKR chimera with respect to GFP-DLP(ct). The structure of the SUMO-KRKR chimera is schematically drawn in the same panel: Drosophila SUMO (amino acids 1–85) is fused to residue 18 of p53 KRKR. Images refer to a single Z section. C, quantification of p53 nuclear dots co-localized with GFP-DLP(ct) dots, assayed with the indicated constructs. More than 460 nuclear p53 dots were counted per mutant, in three independent experiments.

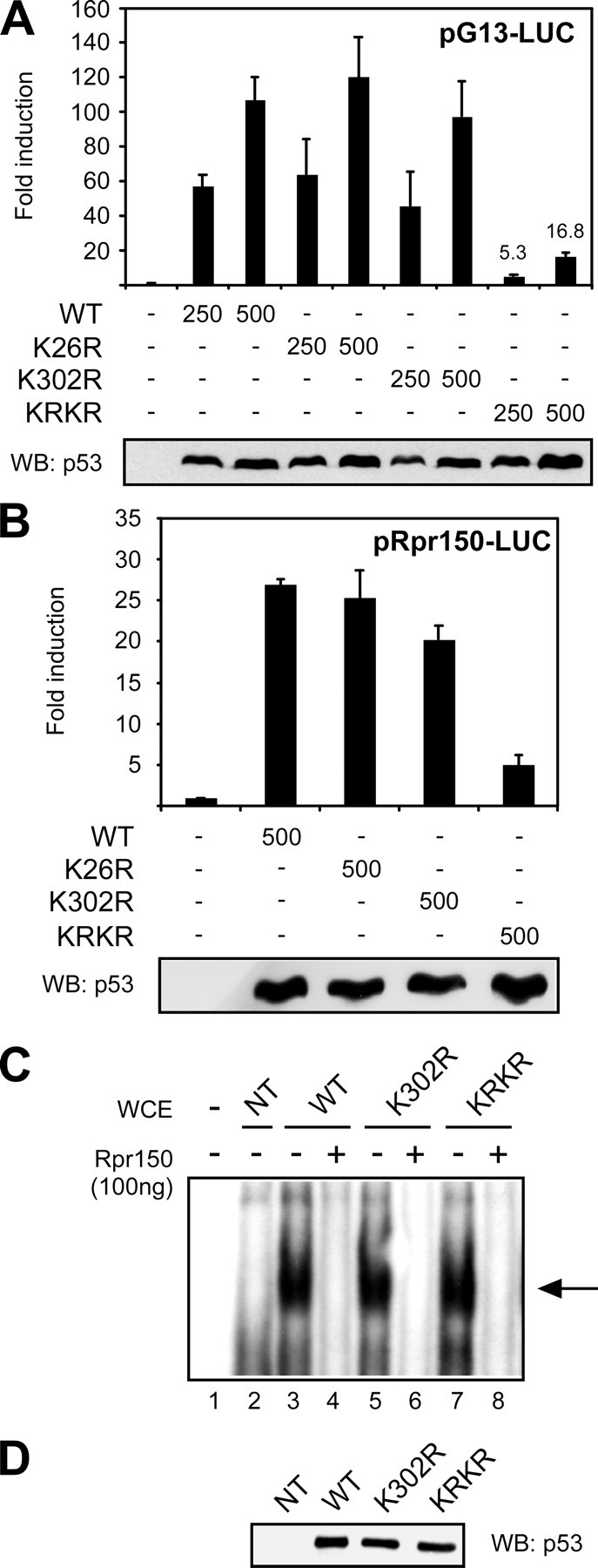

Nonsumoylatable p53 Is Less Active Than the Wild-type Protein in Cultured Cells—Given the conflicting data on the functional relevance of sumoylation in mammalian p53, we asked whether sumoylation might affect the transcriptional activity of Drosophila p53. Initially, we used the pG13-LUC plasmid, a reporter responsive to mammalian p53 (25). We transfected this construct with increasing amounts of expression vectors encoding untagged versions of p53 mutants, and assayed for luciferase. With this reporter, equal expression levels of non-sumoylatable p53 KRKR mutant have significantly less transcriptional activity than wild-type p53 (Fig. 4). In contrast, mutants with substitution of either single lysine display a transactivation activity similar to wild-type p53. To confirm this behavior with a Drosophila promoter element, a luciferase reporter driven by a DNA damage responsive cis-regulatory sequence from the reaper locus, containing a p53 binding site (Rpr150 enhancer) (24), was constructed and tested as above. The nonsumoylatable p53 KRKR mutant was also less active than wild-type p53 or single lysine mutants using this reporter (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Mutation of both sumoylation sites affects transcriptional activity of p53 but not its DNA binding. A, transactivation of a human p53-responsive promoter. The pG13-LUC reporter plasmid was transfected in S2 cells together with increasing amounts of vector expressing wild-type p53 or sumoylation mutants. A plasmid constitutively expressing β-galactosidase was included as a control for transfection efficiency. p53 transcriptional activity was measured by luciferase assay, while the levels of expressed proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting of the same lysates (lower panel). Fold induction values of the p53 KRKR mutant are indicated. Error bars indicate S.E. (n = 4). B, transactivation of a Drosophila p53-responsive promoter. The pRpr150-LUC reporter carrying the p53 binding site from the Reaper DNA-damage responsive enhancer was transfected and assayed as described above. Error bars indicate S.E. (n = 3). C, EMSA. Wild-type p53 and lysine mutants were tested for sequence-specific DNA binding by gel shift, using a double-stranded oligonucleotide containing the p53-responsive element form the Reaper enhancer (Rpr150). Specificity of the binding was confirmed by competition with cold Rpr150 oligonucleotide. Lane 1, free probe. Lanes 2–9, whole cell lysates from S2 cells untransfected (NT) or transfected with the indicated p53 constructs. D, protein levels of transfected p53 mutants were assayed by immunoblotting of the lysates used for EMSA.

To test if the reduced transcriptional activity of p53 KRKR is due to impaired sequence-specific DNA binding, we prepared lysates from transfected S2 cells and performed EMSA using a double-stranded DNA oligonucleotide containing the p53-binding element from the Rpr150 enhancer. As shown in Fig. 4, C and D, the p53 KRKR mutant binds efficiently to the oligonucleotide probe, indicating that mutation of both lysines does not prevent sequence-specific DNA binding.

p53 Sumoylation Sites Are Essential for in Vivo Function—To determine whether sumoylation affects p53 function in vivo, we compared the activity of wild-type and nonsumoylatable p53 in the developing eye. We examined the ability of p53 to induce apoptosis under two conditions, when highly overexpressed and when activated following exposure to IR. Overexpression of p53 using GMR-Gal4 and GUS-p53 results in a rough, reduced eye phenotype, accompanied by a loss of pigmentation in the center of the eye (26, 28) (Fig. 5, A and B). Overexpression of p53 KRKR induces a similar rough eye, but with less loss of pigmentation (Fig. 5C), suggesting a difference in wild-type and mutant p53 activity during eye development.

GMR-Gal4 induces target gene expression beginning in the morphogenetic furrow, which marks cells in the eye imaginal disc as they initiate synchronous cell cycle progression and differentiation. The furrow first forms in cells at the posterior of the disc and moves to increasingly anterior cells. As a result, cells near the furrow have just begun to express the transgene, while more posterior cells have expressed it for longer times. Overexpressed wild-type p53 induces a high level of apoptosis in a band of cells immediately posterior to the furrow, as assayed by activated caspase and TUNEL staining (Fig. 5, D, E, and G and data not shown). In eye discs overexpressing p53 KRKR, the band of apoptosis is initially weaker and extends further posterior from the furrow (Fig. 5, F and G). In these experiments, the mean distance of apoptotic cells is increased from 38.0 (S.E. = 3.0) for wild-type p53 to 59.3 (S.E. = 2.5) for p53KRKR (p = 0.036, two-tailed Student's t test). However, the total number of apoptotic cells is similar; the average number of TUNEL-positive cells is 568 (S.E. = 55.5) for wild-type p53 and is 474 (S.E. = 37.4) for p53KRKR (p = 0.20). Because the distance from the morphogenetic furrow corresponds to the length of time cells have been overexpressing p53, these experiments indicate a delay in the induction of apoptosis by nonsumoylatable p53. This delay could reflect either lower levels of p53 KRKR expression, decreased transcriptional activity of p53 KRKR, or both.

The role of sumoylation in p53 function was also examined during DNA damage induced apoptosis. Drosophila p53 is required for the rapid induction of apoptosis by ionizing radiation (IR) (24, 26) (Fig. 5, H, L, I, M, and P). In the absence of a GAL4 driver, the GUS vector expresses sufficient p53 in the posterior of the eye disc to fully restore IR-induced apoptosis in a p53-null background (28) (Fig. 5, J, N, and P). In contrast, expression of p53 KRKR only weakly rescues IR-induced apoptosis (Fig. 5, K, O, and P). Under these conditions, apoptosis is induced at the same time in all cells, and quantification of cleaved caspase-3 reveals a 6-fold decrease in the level of IR-induced apoptosis in p53KRKR transgenics (Fig. 5P, p = 0.008, Student's t test). The decrease is greatest near the furrow, resulting in a change in the pattern of apoptotic cells. It is important to emphasize that the failure to fully rescue apoptosis is not due to insufficient expression levels, because both the wild-type and mutant p53 transgenes are expressed at higher levels than endogenous p53 (endogenous p53 is not detected by immunofluorescence). These results confirm that the p53 KRKR mutant is less active than the wild-type protein and demonstrate that sumoylation sites are critical for induction of apoptosis by p53 following DNA damage in vivo.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we find that Drosophila p53 has two sites of sumoylation: one at the N terminus and the other in the C-terminal region, before the oligomerization domain. Human p53, as well as p63 and p73, are sumoylated on a single residue at the extreme C terminus (3, 19). Therefore, the modification is conserved, but its position has changed during evolution. In mammalian p53 the last C-terminal amino acids are not required for oligomerization, and serve a regulatory function. In contrast, in Drosophila p53 the C-terminal 24 amino acids form an α-helix that interacts with the oligomerization domain and is required for tetramerization (27). Thus, both in mammals and Drosophila, C-terminal sumoylation of p53 occurs on a site where it should not interfere with oligomerization.

Because of very low expression levels, it is extremely difficult to detect endogenous p53 in Drosophila tissues or cell lines, even after DNA damage stimulation. Although we have not been able to examine endogenous p53, we have demonstrated that p53 is efficiently modified in cells in which SUMO and the SUMO-ligating enzymes are present at physiological levels. Exploration of the signaling pathways that regulate p53 sumoylation in vivo will require the development of reagents and/or techniques to efficiently detect endogenous p53 protein in Drosophila cells.

p53 forms nuclear dots when overexpressed in Drosophila cells in culture and in developing eye imaginal discs. In tissue culture, dots formed by p53 co-localize with dots formed by human PML IV and Drosophila Daxx. It is tempting to speculate that such structures may be related to mammalian PML nuclear bodies. However, an important caveat is that these observations rely on ectopic expression of transfected proteins, because no reagents are available to detect endogenous counterparts. The absence of an obvious PML homolog in Drosophila clearly indicates that these structures are not identical in insects and mammals; however, the recruitment of human PML IV to dots containing Drosophila SUMO, p53, and Daxx homologs does suggest that some aspects are conserved. We find that nonsumoylatable p53 also forms nuclear dots. However, it seems likely that nuclear dots formed by nonsumoylatable p53 are qualitatively different from those formed by the wild-type protein, as suggested by the reduced co-localization with dots marked by GFP-SUMO, hPML IV, and DLP. Thus, the change in localization to specific subnuclear domains correlates with the reduced activity of the p53 KRKR mutant.

Our experiments demonstrate that sumoylation sites are important for the activity of Drosophila p53 both in tissue culture and in vivo. However, the sumoylation-deficient p53 KRKR mutant is not completely inactive; it retains sequence-specific DNA binding, and moderately transactivates both reporter constructs tested (Fig. 4). p53 KRKR also retains some residual ability to induce apoptosis in irradiated imaginal discs, indicating that sumoylation sites are not absolutely required for p53 activation by DNA damage (Fig. 5), but are essential for optimal activity.

It is important to note that single mutation of either sumoylation site had no significant effect on the activity of p53. This implies that modification of a specific lysine is not critical; rather, it is important that SUMO can be attached to the protein. This observation indicates that sumoylation does not simply function to compete with another modification of the same residue (i.e. ubiquitination or acetylation). Our observation that sumoylation is not required for DNA binding suggests that this modification may mediate recruitment of additional factors needed for p53-dependent transcription of target genes. Alternatively, sumoylation may indirectly control p53 modification on other residues via interaction with specific modifying enzymes.

Sumoylation affects turnover of human p63α and p73α (3), but we see no difference in the expression levels of transfected wild-type or mutant p53 in S2 cells, where p53 KRKR has clearly reduced transcriptional activity (Figs. 1 and 4 and data not shown). In contrast, in developing eye discs, p53 KRKR seems to be expressed at lower levels than wild type. This difference may contribute to the difference in apoptosis induced by strong p53 overexpression. However, p53 KRKR cannot rescue DNA damage-induced apoptosis in p53 mutant animals, despite being expressed at much higher levels than endogenous p53 in wild-type animals. (See Figs. 2 and 5; endogenous p53 was not detectable in wild-type cells.) This observation demonstrates that sumoylation sites are critical for induction of apoptosis by p53 in vivo, regardless of the difference in expression levels detected between exogenous wild-type and KRKR p53 proteins in eye discs.

Our results in Drosophila are consistent with studies in mammalian cells reporting that sumoylation promotes p53 function (12, 13, 45), but are in contrast with knock-in mouse models demonstrating that C-terminal lysines are not crucial for p53 function in vivo (5, 19, 20). There are several possible explanations for this discrepancy. First, because knock-in p53 models had mutations in all C-terminal lysines, it is possible that loss of other modification sites masks a specific requirement for sumoylation. Second, human p53 might be sumoylated at additional non-canonical residues (16, 46); a weak secondary site may compensate for loss of the primary sumoylation site. Third, interaction with sumoylated proteins may be sufficient to substitute for direct sumoylation of mammalian p53; these interacting partners may not be present in Drosophila (e.g. PML)(18). Finally, specific features of the molecular regulation of Drosophila p53 may account for a more stringent requirement for sumoylation.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that SUMO attachment is a modification of p53 that is evolutionarily conserved from insects to mammals. Specific requirements for this modification may have changed with the emergence of three p53 paralogs in vertebrates, but sumoylation sites are clearly important for function of the single p53 protein in Drosophila. Our results support the general hypothesis that sumoylation has an important role in regulation of metazoan p53 and p53-related proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. C. Griffith for providing the SUMO antibody, and O. Stemann for sharing S2 cells and plasmids. We wish to acknowledge the contribution of S. Luppi, who performed the very first experiment on Drosophila p53 sumoylation.

This work was supported in part by grants from AIRC (Italian Association for Cancer Research), MIUR (Italian Ministry for University and Research), and EC FP6 contract 503576 (Active p53) (to L. C. and G. D. S.), and by a Research Scholar Grant from the American Cancer Society and a New Scholar in Aging Award from the Ellison Medical Foundation (to M. H. B.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PML, Promyelocytic Leukemia Protein; NB, nuclear bodies; GFP, green fluorescent protein; HA, hemagglutinin; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility shift assay; IR, ionizing radiation; DLP, Daxx-like protein.

M. H. Brodsky and G. Tsang, unpublished results.

References

- 1.Vousden, K. H., and Lane, D. P. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8275 -283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris, S. L., and Levine, A. J. (2005) Oncogene 242899 -2908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson, I. R., and Irwin, M. S. (2006) Neoplasia 8655 -666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bode, A. M., and Dong, Z. (2004) Nat. Rev. Cancer 4793 -805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toledo, F., and Wahl, G. M. (2006) Nat. Rev. Cancer 6909 -923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horn, H. F., and Vousden, K. H. (2007) Oncogene 261306 -1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muller, S., Hoege, C., Pyrowolakis, G., and Jentsch, S. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2 202-210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hay, R. T. (2005) Mol. Cell 18 1-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller, S., Ledl, A., and Schmidt, D. (2004) Oncogene 231998 -2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill, G. (2005) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15536 -541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoeller, D., Hecker, C. M., and Dikic, I. (2006) Nat. Rev. Cancer 6776 -788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez, M. S., Desterro, J. M., Lain, S., Midgley, C. A., Lane, D. P., and Hay, R. T. (1999) EMBO J. 186455 -6461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gostissa, M., Hengstermann, A., Fogal, V., Sandy, P., Schwarz, S. E., Scheffner, M., and Del Sal, G. (1999) EMBO J. 186462 -6471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muller, S., Berger, M., Lehembre, F., Seeler, J. S., Haupt, Y., and Dejean, A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 27513321 -13329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt, D., and Muller, S. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 992872 -2877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwek, S. S., Derry, J., Tyner, A. L., Shen, Z., and Gudkov, A. V. (2001) Oncogene 202587 -2599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Megidish, T., Xu, J. H., and Xu, C. W. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 2778255 -8259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fogal, V., Gostissa, M., Sandy, P., Zacchi, P., Sternsdorf, T., Jensen, K., Pandolfi, P. P., Will, H., Schneider, C., and Del Sal, G. (2000) EMBO J. 196185 -6195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng, L., Lin, T., Uranishi, H., Gu, W., and Xu, Y. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 255389 -5395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krummel, K. A., Lee, C. J., Toledo, F., and Wahl, G. M. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 10210188 -10193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang, Y. P., Wu, G., Guo, Z., Osada, M., Fomenkov, T., Park, H. L., Trink, B., Sidransky, D., Fomenkov, A., and Ratovitski, E. A. (2004) Cell Cycle 31587 -1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghioni, P., D'Alessandra, Y., Mansueto, G., Jaffray, E., Hay, R. T., La Mantia, G., and Guerrini, L. (2005) Cell Cycle 4183 -190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minty, A., Dumont, X., Kaghad, M., and Caput, D. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 27536316 -36323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brodsky, M. H., Nordstrom, W., Tsang, G., Kwan, E., Rubin, G. M., and Abrams, J. M. (2000) Cell 101103 -113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin, S., Martinek, S., Joo, W. S., Wortman, J. R., Mirkovic, N., Sali, A., Yandell, M. D., Pavletich, N. P., Young, M. W., and Levine, A. J. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 977301 -7306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ollmann, M., Young, L. M., Di Como, C. J., Karim, F., Belvin, M., Robertson, S., Whittaker, K., Demsky, M., Fisher, W. W., Buchman, A., Duyk, G., Friedman, L., Prives, C., and Kopczynski, C. (2000) Cell 10191 -101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ou, H. D., Lohr, F., Vogel, V., Mantele, W., and Dotsch, V. (2007) EMBO J. 263463 -3473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brodsky, M. H., Weinert, B. T., Tsang, G., Rong, Y. S., McGinnis, N. M., Golic, K. G., Rio, D. C., and Rubin, G. M. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 241219 -1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, J. H., Lee, E., Park, J., Kim, E., Kim, J., and Chung, J. (2003) FEBS Lett. 550 5-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sogame, N., Kim, M., and Abrams, J. M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1004696 -4701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oikemus, S. R., McGinnis, N., Queiroz-Machado, J., Tukachinsky, H., Takada, S., Sunkel, C. E., and Brodsky, M. H. (2004) Genes Dev. 181850 -1861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akdemir, F., Christich, A., Sogame, N., Chapo, J., and Abrams, J. M. (2007) Oncogene 265184 -5193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peters, M., DeLuca, C., Hirao, A., Stambolic, V., Potter, J., Zhou, L., Liepa, J., Snow, B., Arya, S., Wong, J., Bouchard, D., Binari, R., Manoukian, A. S., and Mak, T. W. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 9911305 -11310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Long, X., and Griffith, L. C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 27540765 -40776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanyon, C. A., Liu, G., Mangiola, B. A., Patel, N., Giot, L., Kuang, B., Zhang, H., Zhong, J., and Finley, R. L., Jr. (2004) Genome Biol. 5R96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Formstecher, E., Aresta, S., Collura, V., Hamburger, A., Meil, A., Trehin, A., Reverdy, C., Betin, V., Maire, S., Brun, C., Jacq, B., Arpin, M., Bellaiche, Y., Bellusci, S., Benaroch, P., Bornens, M., Chanet, R., Chavrier, P., Delattre, O., Doye, V., Fehon, R., Faye, G., Galli, T., Girault, J. A., Goud, B., de Gunzburg, J., Johannes, L., Junier, M. P., Mirouse, V., Mukherjee, A., Papadopoulo, D., Perez, F., Plessis, A., Rosse, C., Saule, S., Stoppa-Lyonnet, D., Vincent, A., White, M., Legrain, P., Wojcik, J., Camonis, J., and Daviet, L. (2005) Genome Res. 15 376-384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melchior, F., and Hengst, L. (2002) Cell Cycle 1245 -249 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gostissa, M., Hofmann, T. G., Will, H., and Del Sal, G. (2003) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15 351-357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lallemand-Breitenbach, V., Zhu, J., Puvion, F., Koken, M., Honore, N., Doubeikovsky, A., Duprez, E., Pandolfi, P. P., Puvion, E., Freemont, P., and de The, H. (2001) J. Exp. Med. 1931361 -1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salomoni, P., and Pandolfi, P. P. (2002) Cell 108165 -170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lehembre, F., Badenhorst, P., Muller, S., Travers, A., Schweisguth, F., and Dejean, A. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 201072 -1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michaelson, J. S. (2000) Apoptosis 5217 -220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salomoni, P., and Khelifi, A. F. (2006) Trends Cell Biol. 1697 -104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bodai, L., Pardi, N., Ujfaludi, Z., Bereczki, O., Komonyi, O., Balint, E., and Boros, I. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 28236386 -36393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li, T., Santockyte, R., Shen, R. F., Tekle, E., Wang, G., Yang, D. C., and Chock, P. B. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 28136221 -36227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jakobs, A., Koehnke, J., Himstedt, F., Funk, M., Korn, B., Gaestel, M., and Niedenthal, R. (2007) Nat. Methods 4245 -250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.