Abstract

Calpain 10 is ubiquitously expressed and is one of four mitochondrial matrix proteases. We determined that over-expression or knock-down of mitochondrial calpain 10 results in cell death, demonstrating that mitochondrial calpain 10 is required for viability. Thus, we studied calpain 10 degradation in isolated mitochondrial matrix, mitochondria and in renal proximal tubular cells (RPTC) under control and toxic conditions. Using isolated renal cortical mitochondria and mitochondrial matrix, calpain 10 underwent rapid degradation at 37° C that was blocked with Lon inhibitors but not by calpain or proteasome inhibitors. While exogenous Ca2+ addition, Ca2+ chelation or exogenous ATP addition had no effect on calpain 10 degradation, the oxidants tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) or H2O2 increased the rate of degradation. Using RPTC, mitochondrial and cytosolic calpain 10 increased in the presence of MG132 (Lon/proteasome inhibitor) but only cytosolic calpain 10 increased in the presence of epoxomicin (proteasome inhibitor). Furthermore, TBHP and H2O2 oxidized mitochondrial calpain 10, decreased mitochondrial, but not cytosolic calpain 10, and pretreatment with MG132 blocked TBHP-induced degradation of calpain 10. In summary, mitochondrial calpain 10 is selectively degraded by Lon protease under basal conditions and is enhanced under and oxidizing conditions, while cytosolic calpain 10 is degraded by the proteasome.

Keywords: Calpain 10, Lon, Renal Proximal Tubular Cells, Degradation, Toxicant, Inhibitors

INTRODUCTION

Fifteen mammalian calpains, Ca2+-activated cysteine proteases, are divided into two groups: typical and atypical [1-2]. Typical calpains contain a Ca2+-binding penta-EF hand in domain IV while atypical calpains do not. Calpains have been shown to be involved in many cellular processes such as: cytoskeletal/membrane rearrangements, signal transduction, cell cycle, and apoptosis. Limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A, gastric cancer, type II diabetes mellitus, Alzheimer’s disease, myocardial infarcts, stroke, and acute kidney injury [3-4] have been linked to calpains.

Calpain 10 is an atypical calpain that is ubiquitously expressed and is localized to the cytosol, mitochondria and nucleus [5-7]. Our laboratory first reported calpain 10 being localized to rabbit kidney mitochondria [5]. Subsequently, mitochondrial calpain 10 has been found in rat and mouse kidney mitochondria [8]. While other laboratories have reported other calpains in the mitochondria [9-10], it is important to note that in our renal models we only detect calpain 10 [5]. Further research revealed that the mitochondrial matrix contains the majority of the mitochondrial calpain 10 activity and mitochondrial calpain 10 cleaves NDUFB8 and NDUFV2 (complex I proteins), ATP synthase β, and ORP150 (ER and mitochondrial chaperone) [5, 11]. After Ca2+ overload, mitochondrial calpain 10 cleaves these substrates, which results in reduced state 3 respiration.

Interestingly, over-expression of calpain 10 induced mitochondrial swelling and cell death [5] and depletion of mitochondrial calpain 10 resulted in apoptosis [12]. These results provide evidence that maintaining homeostatic protein levels of mitochondrial calpain 10 is important for proper cellular function and viability. Much of the physiology and biochemistry of calpain 10 is unknown but it has been shown to be important for insulin secretion in pancreatic β cells and GLUT4 –mediated transport in adipocytes and skeletal muscle [7, 13]. In addition calpain 10 may play a role in renal aging. Renal calpain 10 decreased in aged rats, mice and humans [12] while calpain 10 protein levels did not change in the liver at any age and calpains 1 and 2 did not change in the kidney at any age.

Lon is an ATP-dependent protease that is important in protein quality control in the mitochondrial matrix [14-15]. Specifically, Lon degrades oxidized and misfolded proteins. In eukaryotes, it is a homo-oligmeric complex composed of seven monomers with a molecular weight of approximately 106 kDa [16-17]. Lon contains three domains: the N-terminal domain, the AAA+ domain, and P-domain. The N-terminal domain interacts with protein substrates [18]. The AAA+ domain contains two sub-domains: one is involved in ATP binding and the other is involved in ATP hydrolysis. The P-domain contains the active site (Ser/Lys dyad). There is no known consensus cleaving sequence for Lon, but it favors cleaving between hydrophobic amino acids [19-20]. Lon also degrades substrates linearly into peptides that are approximately 5-30 amino acids long [19-21].

As too much or too little calpain 10 activity results in cell death, we explored the mechanism of mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation.

EXPERIMENTAL

Reagents

Calpain 10 and Heat Shock Protein 60 (HSP60) antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Calpain 10 product number – ab28226, Cambridge, MA). GAPDH and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit/mouse secondary antibodies were obtained from Fitzgerald (Acton, MA) and Pierce (Rockford, IL), respectively. MG132, MG262, epoxomicin and calpeptin were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Percoll was obtained from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ). Trizol was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Reverse-transcriptase and SYBR Green Real-Time PCR kits were obtained from Fermentas Life Sciences (Glen Burnie, MD). Real-Time PCR primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Mitochondrial Isolation

Renal cortical mitochondria were isolated from female New Zealand White rabbits (2 kg) as described previously [5, 22] and resuspended in mitochondrial isolation buffer (0.27 M sucrose, 5 mM Tris-HCl, and 1 mM EGTA pH 7.4) with or without 5 mM malate and 6 mM pyruvate. Mitochondria were further fractionated to isolate the mitochondrial matrix as previously described [5, 23]. Briefly, mitochondria were purified on a Percoll/sucrose gradient followed by swelling of the outer mitochondrial membrane to isolate mitoplasts. Mitoplasts were sonicated briefly followed by centrifugation at 100,000 g at 4° C to obtain the inner mitochondrial membrane and the mitochondrial matrix.

Calpain 10 degradation assays

Whole mitochondria were incubated at 37° C for various times followed by immunoblot analysis. In some experiments, whole mitochondria were pretreated with 10 mM EGTA, 10 μM calpeptin, 1:100 dilution of protease inhibitor cocktail (PI - Sigma), 10 μM CYGAbuK, 10 μM epoxomicin, 10 μM MG132 or 10 μM MG262 for 5 min prior to incubation at 37° C. The Ca2+ experiments used 1.010 mM CaCl2 to neutralize the 1 mM EGTA in the buffer, leaving 10 μM free Ca2+ followed by incubation at 37° C. In other experiments, whole mitochondria were pre-treated with 1 μM antimycin A (AA), Carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP), 50 μM tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) or 100 μM H2O2 for 5 min prior to incubation at 37° C for 15 or 30 min.

RPTC

Renal proximal tubules were isolated from female New Zealand White rabbits (2 kg) by the iron oxide perfusion method and grown on 35-mm dishes, in glucose-free media, until confluent (6 days) as described previously [24-25]. RPTC were treated with either 0.4 mM TBHP, 0.4 mM H2O2, 100 μM cisplatin, 1 μM antimycin A, or 0.5 μM FCCP for various times. At specific time points, cells were harvested and sonicated for 10 sec in homogenization buffer (0.32 M sucrose, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) with protease inhibitor cocktail. Samples were centrifuged at 900 g at 4° C for 10 min, the supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 15,000 g at 4° C for 10 min, to obtain the mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions [5, 26].

Reverse-transcriptase reaction and Real-Time PCR

RPTC treated with TBHP, H2O2 or cisplatin were harvested in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and total RNA isolated following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was quantified by measuring absorbance at 260 and 280 nm. To obtain cDNA, the reverse transcriptase kit (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD) and 1.5 μg of RNA was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-Time PCR was performed on a Stratagene MX 3100P using 5 μL of a 1:5 dilution of cDNA added to 1x SYBR Green master mix and 400 nM primers. Primer sequences were: Calpain 10: sense – 5′-CACCTACCTGCCGGACACA-3′ antisense – 5′-TGCCATGACGGAGACCTCTT-3′, α-Tubulin: sense – 5′-CTCTCTGTCGATTACGGCAAG antisense – 5′-TGGTGAGGATGGAGTTGTAGG.

Immunoblot Analysis

Protein samples were separated by electrophoresis on 4-12% SDS-PAGE gel prior to being transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Nitrocellulose membranes were blocked in a 2.5% non-fat milk/TBST (Tris-buffered saline Tween 20) solution for 1 hr. All primary antibodies were incubated on a shaker overnight at 4° C. Calpain 10, GAPDH and HSP60 antibodies were used at 1:1000 dilution and the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (anti-rabbit or anti-mouse) was used at 1:100,000 dilution for 1 hr at room temperature. An Alpha Innotech imaging system was used to visualize and quantify membranes for immunoreactive proteins using enhanced chemiluminescence detection.

Detection of Oxidized Mitochondrial Calpain 10

Mitochondrial fractions were isolated from RPTC as described above and the Oxyblot kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used as recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, the carbonyl groups in the sample were derivatized with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine to form 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone groups. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis conducted using an antibody directed against 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone.

Statistical Analysis

A Student’s t-test was performed to determine significance between two groups and a one-way ANOVA with a Student-Newman-Keuls test was used to determine significance between multiple groups. The sample size was at least three and a p-value ≤ 0.05 required for statistical significance.

RESULTS

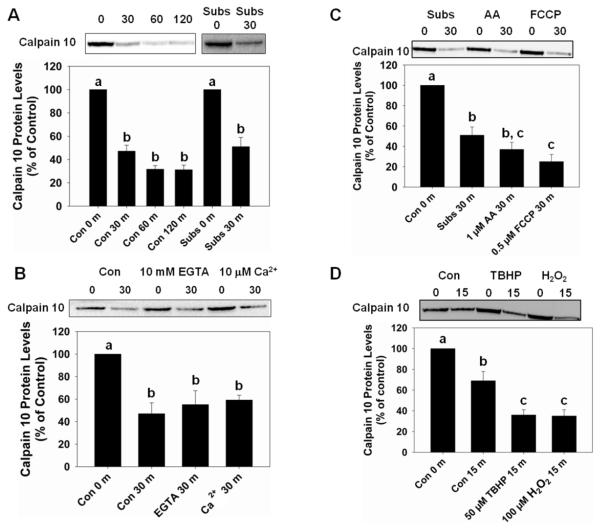

Calpain 10 is degraded in whole mitochondria

To examine mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation in freshly isolated whole mitochondria, we incubated mitochondria at 37° C for 30, 60 and 120 min. At 30 min there was a 53% decrease in calpain 10 protein levels (Figure 1A). At 60 and 120 min, calpain 10 protein levels decreased 68%. To determine whether calpain 10 degradation was altered in mitochondria with a membrane potential, metabolic substrates (5 mM malate/6 mM pyruvate) were added to the medium. Calpain 10 was equally degraded in the presence and absence of metabolic substrates (Figure 1A). Because calpain 10 is a Ca2+-regulated protease we determined if exogenous Ca2+ or chelation altered degradation. Mitochondria with or without metabolic substrates were pretreated with 10 mM EGTA, a Ca2+ chelator, or 10 μM CaCl2 and incubated at 37° C for 30 min. Pretreatment with EGTA or CaCl2 did not affect the rate of calpain 10 degradation in the presence or absence of mitochondrial substrates (Figure 1B, data not shown). These results reveal that mitochondrial calpain 10 is readily degraded at 37° C in the presence and absence of a membrane potential and that Ca2+ does not play a role.

Figure 1.

Calpain 10 degradation in whole mitochondria. A, Incubation of whole mitochondria at 37° C for 30, 60 and 120 min induced calpain 10 degradation in the absence and presence of metabolic substrates (pyruvate/malate, Subs). B, Mitochondria pretreated (5 min) with 10 mM EGTA or 10 μM CaCl2 had no effect on calpain 10 degradation after 30 min. C, Mitochondria pretreated (5 min) with 1 μM antimycin A had no effect effect on calpain 10 degradation while calpain 10 degradation increased in the presence of 0.5 μM FCCP at 30 min. D, Pretreatment of mitochondria with 50 μM TBHP or 100 μM H2O2 for 5 min increased calpain 10 degradation at 15 min. All pretreatments were on ice. Immunoblot analysis was performed on calpain 10 (75 kDa) and quantified by densitometric analysis. Data are represented as means ± SEM of % of control (N ≥ 3 for each group). Bars with different superscripts are statistically different from one another (p ≤ 0.05).

FCCP increases the rate of calpain 10 degradation

We next determined whether inhibition of the electron transport chain, using antimycin A, or dissipation of the proton gradient, using FCCP, altered calpain 10 degradation. While calpain 10 degradation trended to increase in mitochondria + substrates treated with 1 μM antimycin A, the increase was not statistically significant (Figure 1C). In contrast, calpain 10 degradation increased in the presence of 0.5 μM FCCP. Similar results were obtained in mitochondria treated with antimycin A and FCCP in the absence of metabolic substrates (data not shown). These data reveal that calpain 10 degradation is accelerated by dissipating the proton gradient.

Oxidant exposure increases calpain 10 degradation

Because Lon protease has been shown to preferentially cleave oxidized proteins [14], whole mitochondria were pretreated with 50 μM TBHP or 100 μM H2O2 prior to incubation at 37° C for 15 min. The 15 min control exhibited a 31% reduction in calpain 10 protein levels (Figure 1D). Whole mitochondria exposed to TBHP and H2O2 had ~65% reduction in calpain 10. These results provide evidence that calpain 10 is degraded faster under oxidizing conditions.

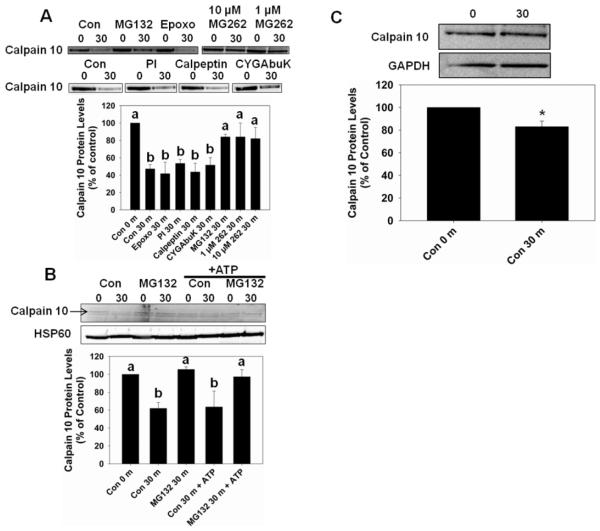

Effect of protease inhibitors on mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation

Whole mitochondria were pretreated for 5 min with a protease inhibitor prior to being incubated at 37° C for 30 min in an attempt to block calpain 10 degradation. The protease inhibitors used were 10 μM calpeptin, 10 μM epoxomicin, 10 μM CYGAbuK, 10 μM MG132, 1 and 10 μM MG262 and a 1:100 dilution of a protease inhibitor cocktail. Calpeptin is a cysteine protease inhibitor [27] and epoxomicin is a specific inhibitor for the proteasome [28]. Our laboratory developed a specific peptide inhibitor for calpain 10, CYGAbuK [29]. MG132 and MG262 are proteasome and Lon inhibitors, while MG132 also inhibits calpains [30]. The protease inhibitor cocktail contains 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF), pepstatin A, E-64, bestatin, leupeptin, and aprotinin.

Figure 2A, reveals that calpain 10 decreased 58% in control mitochondria and that 10 μM MG132, and 1 and 10 μM MG262 blocked calpain 10 degradation. In contrast, in the presence of calpeptin, CYGAbuK and protease inhibitor cocktail calpain 10 degradation was similar to that observed in control mitochondria. Because four different calpain/cysteine inhibitors (calpeptin, CYGAbuK, leupeptin, E-64) did not block degradation, calpain 10 loss was not the result of calpains or other cysteine proteases. Likewise serine protease inhibitors, AEBSF, and aprotinin had no effect on calpain 10 degradation. Epoxomicin also had no effect on calpain 10 degradation, providing evidence that proteasome contamination is not responsible. Consequently, the decrease in calpain 10 degradation produced by MG132 and MG262 is due to Lon inhibition.

Figure 2.

Effect of protease inhibitors on mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation. A, Mitochondria pretreated (5 min) with 10 μM MG132, 1 or 10 μM MG262 blocked mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation after 30 min at 37° C. B, Mitochondrial matrix pretreated with 165 μM ATP or diluent had no effect on calpain 10 degradation. Mitochondrial matrix pretreated (5 min) with 10 μM MG132 blocked calpain 10 degradation after 30 min at 37° C. C, Cytosolic calpain 10 is degraded slower than mitochondrial calpain 10. All pretreatments were on ice. Immunoblot analysis was performed on calpain 10 (75 kDa). HSP60 (60 kDa) and GAPDH (37 kDa) served as loading controls and quantified by densitometric analysis. Data are represented as means ± SEM of % of control (N ≥ 3 for each group). Bars with different superscripts are statistically different from one another (p ≤ 0.05). Bars with * are statistically different from controls (p ≤ 0.05).

Calpain 10 degraded in mitochondrial matrix is not ATP dependent

Because the majority of mitochondrial calpain 10 activity is in the mitochondrial matrix [5], we confirmed the above results using mitochondrial matrix and determined ATP dependency. Mitochondrial matrix was pretreated with 10 μM MG132 or diluent for 5 min prior to the addition of 165 μM ATP or diluent. The samples were incubated at 37° C for 30 min. Calpain 10 protein levels decreased by 38% and this decrease was blocked by MG132 (Figure 2B). The decrease in calpain 10 levels was similar in the presence and absence of 165 or 5,000 μM ATP (Figure 2B, data not shown). These experiments provide additional evidence that Lon degrades calpain 10 and that ATP does not stimulate degradation.

Cysotolic calpain 10 degradation

Since calpain 10 is found in the mitochondria and cytosol we determined if cytosolic calpain 10 undergoes rapid degradation as seen in mitochondria. Cytosol was incubated at 37° C for 30 min and immunoblotted for calpain 10. We found that cytosolic calpain 10 decreased ~20% when incubated at 37° C for 30 min (Figure 2C).

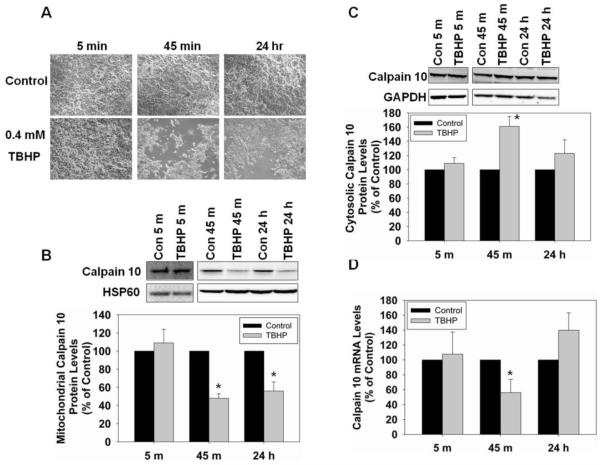

Mitochondrial calpain 10 decreases with TBHP treatment in RPTC

To determine if treatment with an oxidant causes a decrease in mitochondrial calpain 10, RPTC were treated with 0.4 mM TBHP for 5 min or 45 min. After 45 min of TBHP treatment, the media was removed and replaced with fresh media and RPTC were allowed to recover for 24 hr. This concentration of TBHP has been used previously in our laboratory and has been shown to be an effective method for inducing ROS damage in RPTC [31]. Bright field microscopic images of RPTC after 5 min of TBHP exposure revealed no damage, but at 45 min approximately 40% cell loss occurred and by 24 hr there was a slight recovery (Figure 3A). Mitochondrial calpain 10 protein levels did not change at 5 min, but at 45 min there was a 52% decrease in protein, compared to controls. This reduction in mitochondrial calpain 10 protein remained at 24 hr (Figure 3B). In contrast, cytosolic calpain 10 protein did not change at 5 min, but increased 61% at 45 min and returned to control levels at 24 hr (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

TBHP induces degradation of mitochondrial calpain 10 in RPTC. RPTC were treated with 0.4 mM TBHP for 5 min, 45 min and 24 hr, and RNA, and mitochondrial and cystolic fractions harvested. A, Brightfield photomicrographs (100x magnification). B, Immunoblot analysis of mitochondrial calpain 10 (75 kDa). C, Immunoblot analysis of cytosolic calpain 10 (75 kDa). HSP60 (60 kDa) and GAPDH (37 kDa) served as loading controls and quantified by densitometric analysis. D, Calpain 10 mRNA levels were determined by Real-Time PCR with α-tubulin serving as a loading control. Data are represented as means ± SEM of % of control (N ≥ 3 for each group). Bars with * are statistically different from controls (p ≤ 0.05).

Real-Time PCR was used to analyze calpain 10 mRNA levels. While, there was no change in the mRNA level at 5 min, at 45 min calpain 10 mRNA decreased 44% (Figure 3D). At 24 hr, calpain 10 mRNA levels trended to increase to 140% of control. The loss of mitochondrial calpain 10 after 45 min of TBHP exposure is consistent with our whole mitochondria experiments. These results illustrate that mitochondrial calpain 10 is selectively degraded in cells exposed to oxidants while cytosolic calpain 10 is not.

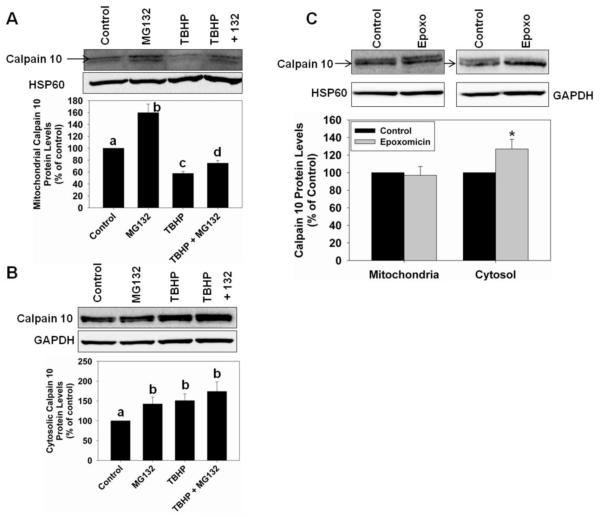

Protease inhibitor pretreatment causes calpain 10 accumulation

In Figure 2, MG132 was shown to decrease mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation in whole mitochondria and mitochondrial matrix. Therefore, we determined if MG132 decreases mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation in RPTC and if it could prevent TBHP-induced mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation. RPTC were pretreated with 10 μM MG132 for 1 hr prior to TBHP or diluent exposure for 45 min. MG132 treatment caused a 1.6-fold accumulation of mitochondrial calpain 10 (Figure 4A). TBHP treatment alone decreased mitochondrial calpain 10 levels, confirming results in Figure 3B. When RPTC were treated with TBHP after MG132 pretreatment, calpain 10 degradation was diminished compared to RPTC treated with TBHP alone (Figure 4A). Cytosolic calpain 10 protein levels also accumulated with MG132 treatment (Figure 4B). This is likely because MG132 also inhibits the proteasome [30]. To confirm this possibility, we treated RPTC with 10 μM epoxomicin for 1.75 hr and observed that cytosolic calpain 10 increased while mitochondrial calpain did not (Figure 4C). These experiments reveal that MG132 causes accumulation of mitochondrial calpain 10 under basal conditions and decreases TBHP-induced calpain 10 degradation, and that cytosolic calpain 10 degradation is blocked with epoxomicin.

Figure 4.

Protease inhibitor pretreatment causes calpain 10 accumulation in RPTC. RPTC were pretreated with 10 μM MG132 for 1 h followed by 0.4 mM TBHP treatment for 45 min and mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were harvested. A, Immunoblot analysis of mitochondrial calpain 10 (75 kDa). B, Immunoblot analysis of cytosolic calpain 10 (75 kDa). C, RPTC were treated with 10 μM epoxomicin for 1.75 hr and mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were harvested. Immunoblot analysis of mitochondrial and cytosolic calpain 10 (75 kDa). HSP60 (60 kDa) and GAPDH (37 kDa) served as loading controls and quantified by densitometric analysis. Data are represented as means ± SEM of % of control (N ≥ 3 for each group). Bars with different superscripts are statistically different from one another (p ≤ 0.05). Bars with * are statistically different from controls (p ≤ 0.05).

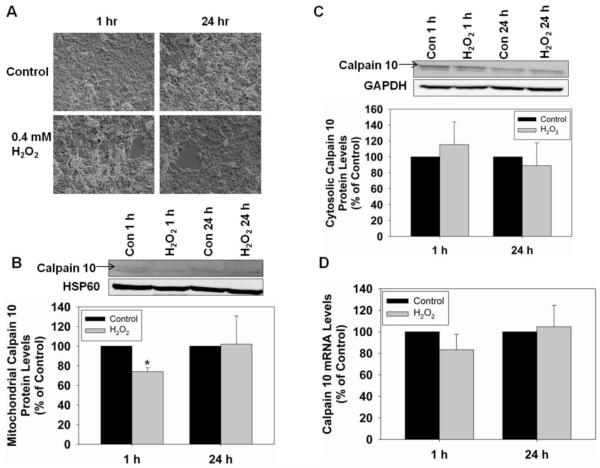

Mitochondrial calpain 10 decreases with H2O2 treatment

To determine if another oxidant produces similar results to TBHP, we treated RPTC with 0.4 mM H2O2 for 1 and 24 hr. Figure 5A shows bright field microscopic images of RPTC treated with H2O2. At both times there was approximately 15% cell loss, a lesser degree of damage compared to TBHP treatment. Mitochondrial calpain 10 protein at 1 hr decreased 24% (Figure 5B) and returned to control levels at 24 hr. Cytosolic calpain 10 protein was unaffected at 1 or 24 hr with H2O2 treatment (Figure 5C). Real-Time PCR analysis of the calpain 10 mRNA revealed no change in mRNA levels at any time point (Figure 5D). These results reveal that limited oxidative stress selectively decreases mitochondrial calpain.

Figure 5.

H2O2 induces rapid degradation of mitochondrial calpain 10 in RPTC. RPTC were treated with 0.4 mM H2O2 for 1 and 24 h and RNA, and mitochondrial and cystolic fractions harvested. A, Brightfield photomicrographs (100x magnification). B, Immunoblot analysis of mitochondrial calpain 10 (75 kDa). C, Immunoblot analysis of cytosolic calpain 10 (75 kDa). HSP60 (60 kDa) and GAPDH (37 kDa) served as loading controls and quantified by densitometric analysis. D, Calpain 10 mRNA levels were determined by Real-Time PCR with α-tubulin serving as a loading control. Data are represented as means ± SEM of % of control (N ≥ 3 for each group). Bars with * are statistically different from controls (p ≤ 0.05).

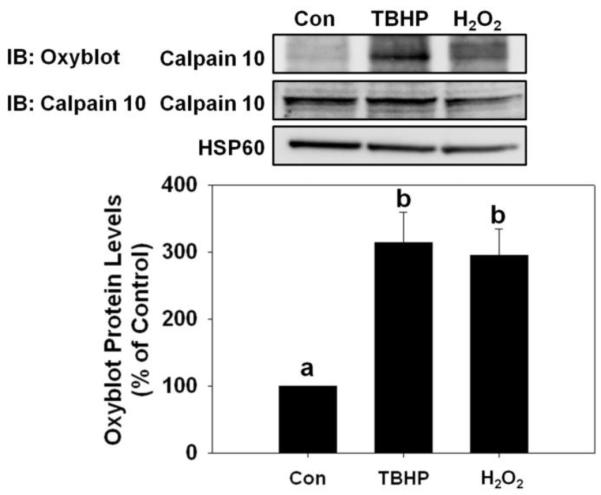

Mitochondrial calpain 10 is oxidized by TBHP and H2O2 treatment

To determine if mitochondrial calpain 10 is oxidized by TBHP and H2O2, we measured protein carbonyl groups using an Oxyblot kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA). RPTC were treated for 30 minutes with 400 μM TBHP or H2O2 for 30 minutes, prior to significant mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation. A light staining band of 75 kDa corresponding to mitochondrial calpain 10 was observed on the oxyblot in mitochondria isolated from control RPTC (Figure 6). Following TBHP and H2O2 exposure strong staining bands on the oxyblot were observed at the 75 kDa. Quantification of these bands revealed a 3-fold increase in staining following oxidant exposure.

Figure 6.

Detection of oxidized calpain 10. RPTC were treated with 400 μM TBHP or H2O2 30 min and the mitochondrial fraction was harvested. Immunoblot analysis of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone and calpain 10. The calpain 10 antibody detects a band that is slightly below 75 kDa. HSP60 (60 kDa) served as loading controls and quantified by densitometric analysis. Data are represented as means ± SEM of % of control (N ≥ 3 for each group). Bars with different superscripts are statistically different from one another (p ≤ 0.05).

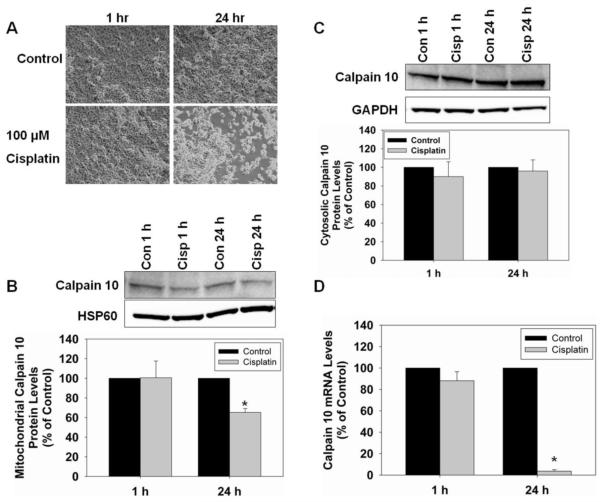

Mitochondrial calpain 10 in cisplatin toxicity

To determine whether a different cellular toxicant causes a decrease in mitochondrial calpain 10 protein levels we treated RPTC with 100 μM cisplatin. Cisplatin is an anti-cancer drug that causes nephrotoxicity and apoptosis, and we have previously characterized the toxicity of cisplatin in our RPTC model [32]. RPTC were treated with 100 μM cisplatin for 1 hr and 24 hr. Bright field microscopic images show little cell death at 1 hr but by 24 hr there was approximately 30% apoptosis and cell loss (Figure 6A). Mitochondrial calpain 10 protein did not change at 1 hr but decreased 35% at 24 hr (Figure 6B). Cytosolic calpain 10 protein did not change at 1 or 24 hr (Figure 6C). Real-Time PCR revealed no change in calpain 10 mRNA at 1 hr but a 96% decrease at 24 hr (Figure 6D). These results provide additional evidence that mitochondrial calpain 10 is selectively lost in toxicant injury.

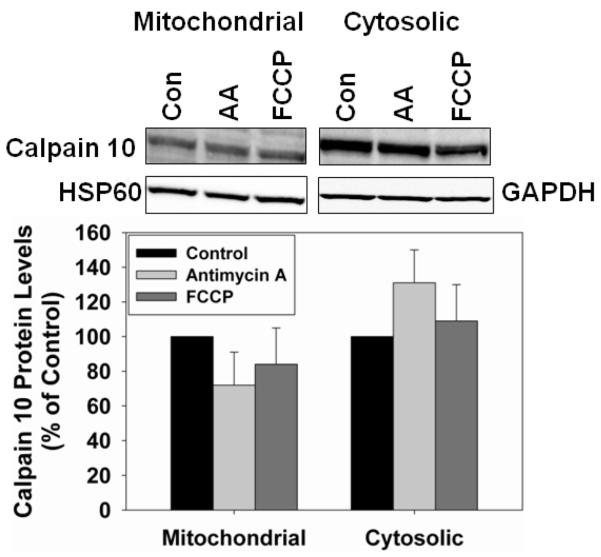

Mitochondrial respiration inhibitors and calpain 10

To determine whether inhibition of the electron transport chain (antimycin A) or dissipating the proton gradient with an uncoupler (FCCP) affects mitochondrial calpain 10, we treated RPTC with 1 μM antimycin A and 0.5 μM FCCP for 1 hr, time points that precede cell death. There was no change in mitochondrial or cytosolic calpain 10 levels in the presence or absence of FCCP or antimycin A (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Mitochondrial calpain 10 in cisplatin toxicity. RPTC were treated with 100 μM cisplatin for 1 and 24 hr and RNA, and mitochondrial and cystolic fractions harvested. A, Brightfield photomicrographs (100x magnification). B, Immunoblot analysis of mitochondrial calpain 10 (75 kDa). C, Immunoblot analysis of cytosolic calpain 10 (75 kDa). HSP60 (60 kDa) and GAPDH (37 kDa) served as loading controls and quantified by densitometric analysis. D, Calpain 10 mRNA levels were determined by Real-Time PCR with α-tubulin serving as a loading control. Data are represented as means ± SEM of % of control (N ≥ 3 for each group). Bars with * are statistically different from controls (p ≤ 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Because we have shown that maintaining homeostatic levels of mitochondrial calpain 10 is important for cell viability [5, 12], mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation was examined under several conditions. In whole mitochondria and mitochondrial matrix, mitochondrial calpain 10 was rapidly degraded and Lon protease inhibitors, MG132 and MG262, prevented calpain 10 degradation. Additionally, treating mitochondria with oxidants (i.e. TBHP or H2O2) increased the rate of degradation. This is consistent with a previous report that Lon protease preferentially degrades oxidized proteins [14, 33]. Using RPTC, we demonstrated that the Lon protease inhibitor, MG132, causes an accumulation of mitochondrial calpain 10. TBHP and H2O2 rapidly oxidize and decrease mitochondrial calpain 10 and MG132 pretreatment blocks oxidant-induced loss of mitochondrial calpain 10. Taken together, mitochondrial calpain 10 is degraded by Lon protease under control conditions and is enhanced under oxidizing conditions. Additionally, using RPTC we show that epoxomicin-mediated proteasome inhibition caused accumulation of cytosolic calpain 10, defining the degradation pathway of cytosolic calpain 10.

While the exact physiological and pathological roles of mitochondrial calpain 10 have not been determined, it is known to decrease electron transport chain activity in the presence of elevated Ca2+ levels by hydrolyzing Complex I proteins (NDUFB8 and NDUFV2) and ATP synthase β. In contrast, loss of mitochondrial calpain 10 results in the accumulation of NDUFB8 and ATP synthase β. As such, calpain 10 is one of four mitochondrial matrix proteases. During oxidative stress, Lon-mediated degradation of calpain 10 may serve as a protective role with the goal of preserving mitochondrial proteins and function to facilitate mitochondrial and cellular repair. This is supported by previous reports that Lon preferentially degrades oxidized proteins [14, 33] and our observation that pretreatment of whole mitochondria and RPTC with TBHP and H2O2 resulted in increased degradation of mitochondrial calpain 10. Alternatively, the buildup of calpain 10 substrates may contribute to mitochondrial and cellular injury.

Using rabbit renal cortical mitochondria and mitochondrial matrix, we determined that cysteine proteases, calpains, and the proteasome were not responsible for mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation (Figure 2). In addition, a calpain 10 inhibitor and Ca2+ chelation had no effect on mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation; suggesting autolysis does not occur (Figures 2A and 1B). While the Lon protease inhibitors MG132 and MG262 blocked calpain 10 degradation, these inhibitors also have been reported to inhibit calpains (MG132 only), the proteasome and Lon [30]. Through the use of four other calpain/cysteine protease inhibitors and one specific proteasome inhibitor, we conclude that MG132/262 prevents calpain 10 degradation by inhibiting Lon. Another soluble mitochondrial matrix protease, ClpP, is involved in protein quality control [34]. We do not believe that ClpP is involved in mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation because Haynes et al., showed that 50 μM MG132 only inhibited approximately 50% of purified ClpP activity [35] and in our model we are able to completely inhibit mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation with 10 μM MG132. While our attempts to confirm these data using Lon siRNA in our primary RPTC were unsuccessful because knock down of Lon could not be obtained, we think our use of Lon inhibitors are valid based on the above data and previously published articles [30, 36].

Since Lon is classified as an ATP-dependent protease we expected the addition of ATP would increase Lon activity, and more rapidly degrade mitochondrial calpain 10. However, ATP had no effect on the kinetics of calpain 10 degradation (Figure 2B). Bota and Davies characterized Lon degradation of aconitase and oxidized aconitase using purified protein and mitochondrial matrix [14]. Using purified protein, they showed that without ATP Lon degraded aconitase and oxidized aconitase but at 30% of the rate of the Lon + ATP group. Similar experiments were performed with mitochondrial matrix and the group without ATP degraded aconitase and oxidized aconitase at 20% and 50% of the rate of the mitochondrial matrix + ATP group, respectively. Therefore, under these conditions, ATP is not a requirement for Lon-mediated calpain 10 degradation.

Because Lon degraded mitochondrial calpain 10 in our whole mitochondria experiments, we wanted to determine if Lon was responsible for mitochondrial calpain 10 hydrolysis in RPTC under control conditions and following oxidant exposure. Mitochondrial fractions isolated from RPTC treated with MG132 exhibited a marked increase in calpain 10 (Figure 4A). Treating RPTC with TBHP caused a rapid decrease in mitochondrial calpain 10 by 45 min and this decrease remained at 24 hr (Figure 3B). RPTC pretreated with MG132 for 1 hr prior to TBHP exposure for 45 min resulted in less mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation (Figure 4A), revealing that Lon degrades mitochondrial calpain 10 under control and oxidizing conditions in cells.

In contrast, cytosolic calpain 10 from RPTC treated with TBHP exhibited increased protein levels of approximately 60% at 45 min, before returning to control levels at 24 hr (Figure 3C). This was unexpected, but shows that cytosolic calpain 10 is not targeted for degradation following oxidative stress. In addition, we propose that the decrease in mitochondrial calpain 10 when cytosolic calpain 10 is increased is due to inhibition of mitochondrial import of cytosolic calpain 10. There has been at least one report that oxidative stress inhibits mitochondrial protein import [37]. While we have previously reported that the first 15 amino acids on the N-terminus is responsible for mitochondrial import [5], the regulation of this import under control and oxidative stress is not known. Alternatively, the increase in cytosolic calpain 10 could be the result of oxidant-induced proteasome inhibition. There have been several reports of oxidant-induced proteasome inhibition[38-42]. It is possible that mitochondrial calpain 10 is being exported to the cytosol after TBHP treatment, but we do not believe this is occurring because of two reasons. H2O2 causes a decrease in mitochondrial calpain 10, albeit to a lesser extent than TBHP, but has no effect on cytosolic calpain 10 protein or mRNA. If oxidant stress was causing an exportation of mitochondrial calpain 10 then why does H2O2 not cause a similar effect. The other reason is that the amount of cytosolic calpain 10 is much greater than mitochondrial calpain 10. We have shown how knockdown of calpain 10 results in reduction of the mitochondrial form much quicker than the cytosolic form [12, 43]. Thus, there is always a gradient from the cytosol to the mitochondria, so it is unlikely that there is ever a reversal of this gradient [43].

Mitochondrial calpain 10 was decreased by TBHP, H2O2 and cisplatin in the absence of changes in cytosolic calpain 10 and whether calpain 10 mRNA decreased or not. The main similarity between these toxicants is that they are produce oxidative stress. In contrast, the specific mitochondrial toxicants antimycin A and FCCP did not alter mitochondrial or cytosolic calpain 10 protein levels in RPTC (Figure 7).

Little is known concerning the degradation of cytosolic calpain 10. Using cytosol, calpain 10 was degraded but not as rapidly as in mitochondria (Figure 2C). Since epoxomicin is a specific inhibitor of the proteasome [28], we treated RPTC with epoxomicin and showed that cytosolic calpain 10 accumulated (Figure 4C), providing evidence that cytosolic calpain 10 is degraded by the proteasome.

The observation that calpain 10 was rapidly degraded in whole renal cortical mitochondria or mitochondrial matrix at 37° C was surprising but consistent. Since we have previously shown that mitochondria isolated by these methods are healthy and have high ADP-stimulated oxygen consumption [5], we do not propose the rapid degradation is the result of damaged mitochondria. Furthermore, mitochondrial calpain 10 was rapidly degraded in RPTC mitochondria exposed to oxidants. We propose that mitochondrial calpain 10 is susceptible to oxidation, particularly from ROS produced in the mitochondrial matrix and that oxidation may be a primary mechanism by which mitochondria calpain 10 is regulated. However, it is possible that a protective/regulatory mitochondrial calpain 10 binding protein is lost under these in vitro conditions. In contrast, even though cytosolic calpain 10 and mitochondrial calpain 10 are thought to be equivalent, cytosolic calpain 10 was not readily degraded by the proteasome in the cytosol under control and oxidizing conditions. There are a number of reasons why these differences exist and include 1) different oxidative environments, 2) different mechanisms of degradation, and 3) different protective/regulatory associated proteins.

In summary, mitochondrial calpain 10 is selectively degraded by Lon protease under basal conditions and is enhanced under oxidizing conditions while cytosolic calpain is degraded by the proteasome. Understanding calpain 10 regulation is important, considering calpain 10 needs to be maintained within a specific level to maintain renal cell health.

Highlights.

Heat and oxidant stress induce mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation

Lon inhibitors are able to prevent mitochondrial calpain 10 degradation

Epoxomicin, a proteasome inhibitor, causes an accumulation in cytosolic calpain 10

Figure 8.

Mitochondrial respiration inhibitors and calpain 10. RPTC were treated with 1 μM antimycin A or 0.5 μM for 1 hr and mitochondrial and cystolic fractions harvested. Immunoblot analysis of mitochondrial and cytosolic calpain 10 (75 kDa). HSP60 (60 kDa) and GAPDH (37 kDa) served as loading controls and quantified by densitometric analysis. Data are represented as means ± SEM of % of control (N ≥ 3 for each group). Bars with * are statistically different from controls (p ≤ 0.05).

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This study was supported by NIH Grant [GM 084147], the NIH/NIEHS Training Program in Environmental Stress Signaling [T32ES012878-05], and by the Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Animal facilities were funded by NIH grant [C06 RR-015455].

Abbreviations

- RPTC

renal proximal tubular cells

- TBHP

tert-butyl hydroperoxide

- HSP60

heat shock protein 60

- AA

antimycin A

- FCCP

Carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone

- PI

protease inhibitor cocktail

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLAIMER

The contents of this manuscript do not represent the views of the Department of Veteran Affairs or the United States Government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goll DE, et al. The Calpain System. Physiological Reviews. 2003;83(3):731–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suzuki K, et al. Structure, Activation, and Biology of Calpain. Diabetes. 2004;53(suppl 1):S12–S18. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.s12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatterjee PK, et al. Calpain inhibitor-1 reduces renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in the rat. Kidney Int. 2001;59(6):2073–2083. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatterjee PK, et al. Inhibitors of calpain activation (PD150606 and E-64) and renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2005;69(7):1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arrington DD, Van Vleet TR, Schnellmann RG. Calpain 10: a mitochondrial calpain and its role in calcium-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 2006;291(6):C1159–C1171. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00207.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma H, et al. Characterization and Expression of Calpain 10. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(30):28525–28531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100603200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall C, et al. Evidence that an Isoform of Calpain-10 Is a Regulator of Exocytosis in Pancreatic {beta}-Cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(1):213–224. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giguere CJ, Covington MD, Schnellmann RG. Mitochondrial calpain 10 activity and expression in the kidney of multiple species. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2008;366(1):258–262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozaki T, et al. Characteristics of Mitochondrial Calpains. Journal of Biochemistry. 2007;142(3):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia M, Bondada V, Geddes JW. Mitochondrial localization of [mu]-calpain. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2005;338(2):1241–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arrington DD, Schnellmann RG. Targeting of the molecular chaperone oxygen-regulated protein 150 (ORP150) to mitochondria and its induction by cellular stress. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 2008;294(2):C641–C650. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00400.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Covington MD, Arrington DD, Schnellmann RG. Calpain 10 is required for cell viability and is decreased in the aging kidney. American Journal of Physiology - Renal Physiology. 2009;296(3):F478–F486. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90477.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paul DS, et al. Calpain facilitates GLUT4 vesicle translocation during insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in adipocytes. Biochem. J. 2003;376(3):625–632. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bota DA, Davies KJA. Lon protease preferentially degrades oxidized mitochondrial aconitase by an ATP-stimulated mechanism. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(9):674–680. doi: 10.1038/ncb836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bender T, et al. The role of protein quality control in mitochondrial protein homeostasis under oxidative stress. PROTEOMICS. 2010;10(7):1426–1443. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stahlberg H, et al. Mitochondrial Lon of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a ring-shaped protease with seven flexible subunits. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(12):6787–6790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang N, et al. A human mitochondrial ATP-dependent protease that is highly homologous to bacterial Lon protease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90(23):11247–11251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friguet B, Bulteau A-L, Petropoulos I. Mitochondrial protein quality control: Implications in ageing. Biotechnology Journal. 2008;3(6):757–764. doi: 10.1002/biot.200800041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Melderen L, et al. ATP-dependent Degradation of CcdA by Lon Protease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(44):27730–27738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishii W, et al. The unique sites in SulA protein preferentially cleaved by ATP-dependent Lon protease from Escherichia coli. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2002;269(2):451–457. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ondrovičová G, et al. Cleavage Site Selection within a Folded Substrate by the ATP-dependent Lon Protease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(26):25103–25110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schnellmann RG, Cross TJ, Lock EA. Pentachlorobutadienyl--cysteine uncouples oxidative phosphorylation by dissipating the proton gradient. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1989;100(3):498–505. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(89)90297-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams SD, Gottlieb RA. Inhibition of mitochondrial calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) attenuates mitochondrial phospholipid loss and is cardioprotective. Biochem. J. 2002;362(1):23–32. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nowak G, Schnellmann RG. Improved culture conditions stimulate gluconeogenesis in primary cultures of renal proximal tubule cells. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 1995;268(4):C1053–C1061. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nowak G, Schnellmann RG. L-ascorbic acid regulates growth and metabolism of renal cells: improvements in cell culture. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 1996;271(6):C2072–C2080. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.6.C2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nowak G, et al. Activation of ERK1/2 pathway mediates oxidant-induced decreases in mitochondrial function in renal cells. American Journal of Physiology - Renal Physiology. 2006;291(4):F840–F855. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00219.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pintér M, et al. Calpeptin, a calpain inhibitor, promotes neurite elongation in differentiating PC12 cells. Neuroscience Letters. 1994;170(1):91–93. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meng L, et al. Epoxomicin, a potent and selective proteasome inhibitor, exhibits in vivo antiinflammatory activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(18):10403–10408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasbach KA, et al. Identification and Optimization of a Novel Inhibitor of Mitochondrial Calpain 10. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;52(1):181–188. doi: 10.1021/jm800735d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frase H, Hudak J, Lee I. Identification of the Proteasome Inhibitor MG262 as a Potent ATP-Dependent Inhibitor of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium Lon Protease†. Biochemistry. 2006;45(27):8264–8274. doi: 10.1021/bi060542e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Funk JA, Odejinmi S, Schnellmann RG. SRT1720 Induces Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Rescues Mitochondrial Function after Oxidant Injury in Renal Proximal Tubule Cells. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2010;333(2):593–601. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.161992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boerner LJK, Zaleski JM. Metal complex-DNA interactions: from transcription inhibition to photoactivated cleavage. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2005;9(2):135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bota DA, Ngo JK, Davies KJA. Downregulation of the human Lon protease impairs mitochondrial structure and function and causes cell death. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2005;38(5):665–677. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu AYH, Houry WA. ClpP: A distinctive family of cylindrical energy-dependent serine proteases. FEBS Letters. 2007;581(19):3749–3757. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haynes CM, et al. ClpP Mediates Activation of a Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response in C. elegans. Developmental Cell. 2007;13(4):467–480. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bayot A, et al. Towards the control of intracellular protein turnover: Mitochondrial Lon protease inhibitors versus proteasome inhibitors. Biochimie. 2008;90(2):260–269. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright G, et al. Oxidative Stress Inhibits the Mitochondrial Import of Preproteins and Leads to Their Degradation. Experimental Cell Research. 2001;263(1):107–117. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishizawa-Yokoi A, et al. The 26S Proteasome Function and Hsp90 Activity Involved in the Regulation of HsfA2 Expression in Response to Oxidative Stress. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2010;51(3):486–496. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friguet B, Szweda LI. Inhibition of the multicatalytic proteinase (proteasome) by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal cross-linked protein. FEBS Letters. 1997;405(1):21–25. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.SITTE N, et al. Proteasome inhibition by lipofuscin/ceroid during postmitotic aging of fibroblasts. The FASEB Journal. 2000;14(11):1490–1498. doi: 10.1096/fj.14.11.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strack PR, Waxman L, Fagan JM. Activation of the Multicatalytic Endopeptidase by Oxidants. Effects on Enzyme Structure†. Biochemistry. 1996;35(22):7142–7149. doi: 10.1021/bi9518048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reinheckel T, Grune T, Davies K. The measurement of protein degradation in response to oxidative stress. Methods of Molecular Biology. 2000;99:49–60. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-054-3:49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Covington MD, Schnellmann RG. Chronic high glucose downregulates mitochondrial calpain 10 and contributes to renal cell death and diabetes-induced renal injury. Kidney Int. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]