Video abstract

Video (47.3MB, avi)

Keywords: multiple sclerosis, treatment initiation, management, patient attitudes, adherence

Abstract

Background

Treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) with disease-modifying drugs (DMDs) can reduce relapse frequency and delay disability progression. Although adherence to DMDs is difficult to measure accurately, evidence suggests that poor adherence is common and can compromise treatment success. There are likely to be multiple factors underlying poor adherence. To better understand these factors, the global MS Choices Survey investigated patient and physician perspectives regarding key aspects of MS diagnosis, treatment adherence and persistence, and disease management.

Methods

The survey was conducted in seven countries and involved patients with MS (age 18–60 years; MS diagnosis for ≥1 year; current treatment with a DMD) and physicians (neurologist for 3–30 years; treating ≥15 patients with MS per average month; >60% of time spent in clinical practice). Separate questionnaires were used for physicians and patients, each containing approximately 30 questions.

Results

Questionnaires were completed by 331 patients and 280 physicians. Several differences were observed between the responses of patients and physicians, particularly for questions relating to treatment adherence. Overall, the proportion of patients reporting taking a treatment break (31%) was almost twice that estimated by physicians (on average 17%). The reasons cited for poor adherence also differed between patients and physicians. For example, more physicians cited side effects as the main reason for poor patient adherence (82%), than responding patients (42%).

Conclusions

Physicians may underestimate the scale of poor adherence to DMDs, which could impact on their assessment of treatment efficacy and result in inappropriate treatment escalation. In addition, disparities were identified between patient and physician responses regarding the underlying reasons for poor adherence. Improvements in the dialog between patients and neurologists may increase adherence to DMDs.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, heterogeneous, immune-mediated, demyelinating, neurodegenerative disorder of the central nervous system.1 It is the most common cause of neurological disability in young adults,2,3 affecting an estimated 2.5 million people worldwide.4 The most common form of MS follows a relapsing–remitting course, characterized by episodes of neurological dysfunction followed by remission, often with increased levels of residual disability.5,6 Although MS is currently incurable, several disease-modifying drugs (DMDs) are available to reduce relapse frequency and severity, and to control disease progression. Most require parenteral administration.

To gain the full potential benefit from treatment for any illness, including MS, patients need to adhere to their prescribed regimen. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines adherence as “... the extent to which a person’s behaviour – taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes – corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider”.7 The concept of adherence requires the individual to accept the necessity for the medication, and to persist with the therapy. Adherence, therefore, recognizes the patient as the driver of treatment success,8 whereas the term “compliance” refers only to the need for patients to follow instructions. Adherence can be described as the sum of acceptance, compliance, and persistence.

Adherence to long-term therapy for chronic diseases tends to be poor; the WHO estimates that the average rate of adherence to medications for chronic diseases is as low as 50% in developed countries, and may be even lower in developing countries.7 These estimates highlight the fact that poor adherence to medication is a serious problem that needs to be addressed.

It is difficult to assess accurately the degree of adherence in patients receiving chronic treatment, and few studies have directly assessed levels of adherence to MS therapy. However, evidence suggests that there is a high level of nonadherence to DMDs in patients with MS. A survey of 798 patients with MS showed that approximately 37% of patients were nonadherent to DMDs (defined as having missed one or more injections in the previous 4 weeks).9 Another study retrospectively calculated the medication possession ratio (MPR; defined as the number of days’ supply of disease-modifying therapy dispensed divided by the number of days evaluated) for 6680 patients with MS who had received at least one DMD between 1999 and 2008. The analysis found that between 52% and 62% of patients were adherent to therapy (defined as having an MPR ≥80%).10 A similar database analysis of 2446 patients found that 60% of patients were treatment adherent by the same definition.11

Suboptimal levels of treatment adherence may result in suboptimal outcomes. Patients with poor levels of adherence have a higher risk of relapse11,12 and hospitalization for MS,11 as well as incurring higher MS-related medical costs.11 Additionally, it is important for patients with MS to maintain high levels of treatment exposure over the long term. Data from the PRISMS (Prevention of Relapses and disability by Interferon beta-1a Subcutaneously in Multiple Sclerosis) long-term follow-up study showed that patients with high levels of exposure to subcutaneous (sc) interferon (IFN) β-1a (based on cumulative dose or cumulative time on treatment) had lower rates of relapse and Expanded Disability Status Scale progression, and were less likely to convert to secondary progressive MS than were patients with low levels of exposure to sc IFN β-1a.13

In order to improve treatment adherence in patients with a chronic illness, it is vital to first understand why some patients do not take their medication. Several factors appear to interact to drive poor adherence in patients with MS. A 2009 study found that the most common reason for patients missing an injection was simply that they forgot to administer their treatment.9 Treatment fatigue was also a factor, with some patients reporting that they did not take their medication because they did not feel like it.9 Perceived lack of efficacy is a leading cause of longer interruptions to MS therapy,14 and to remain motivated and adhere to therapy, patients need to believe in the value of their treatment and the benefits it confers.8 As MS is currently incurable, the DMDs used in MS are intended to slow disease progression, so if patients experience few or no clinical signs of disease, they may not appreciate the importance of remaining adherent to treatment. On the other hand, some patients do experience breakthrough disease while on treatment and consequently may perceive their treatment as ineffective and not worth taking. In these cases it is unclear as to what extent the signs of MS may have worsened without treatment. If patients subsequently become nonadherent, their MS is more likely to be problematic. Adverse events (AEs) associated with treatment can negatively affect adherence to and persistence with MS therapies.9,14 In the period shortly after treatment initiation, patients are particularly at risk of discontinuation of treatment because of AEs. Later AEs become less of a problem because many of them diminish with time.15

Given the difficulty of accurately assessing adherence and the various factors contributing to poor adherence, it is important to better understand the views and experiences of both physicians and patients regarding MS therapies. It is particularly worth noting that patients’ perception of their adherence and general experience with therapy may differ from that of their physicians. The MS Choices Survey was commissioned by Merck Serono S.A. – Geneva, Switzerland and performed by GfK Healthcare, London, UK. It investigated patient and physician perspectives on the diagnosis, treatment, and management of MS. Further, the survey sought to identify any discrepancies between the attitudes of patients and those of their physicians. Here, we present the findings of the survey associated with treatment initiation and continuation, as well as factors influencing treatment adherence.

Methods

Study design

Recruitment of respondents

Patients and physicians from seven countries (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK) were recruited. These countries were selected to give a broad overview of MS from three different continents and to provide a good representation of countries with a high prevalence of MS.16 Countries from both northern and southern Europe were represented to enable assessment of different regional attitudes to treatment. Physicians were recruited via an agency online panel; patients were recruited through health care professionals, panels, and other sources such as patient associations.

Inclusion criteria for physicians were that they had been practicing as a neurologist for 3–30 years, treated at least 15 patients with MS in an average month, and spent more than 60% of their time in clinical practice. Physicians completed a computer-assisted web interview, with enrollment eligibility determined through a series of initial screening questions.

Inclusion criteria for patients were that they were aged 18–60 years, had a diagnosis of MS made at least 1 year previously, and were currently being treated with a DMD. At the time of the survey, all available DMDs were administered parenterally. Patients who completed the survey were not necessarily those treated by the responding physicians.

Data collection

The survey consisted of two questionnaires: one for physicians and the other for patients (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The questionnaires underwent preliminary pilot testing in February 2009 to ensure that respondents fully understood all questions and that the overall flow of the survey was logical and conducive to research aims.

The data were mainly collected between May and June 2009. Data collection complied with international market research regulations for reporting AEs associated with MS therapy, thus ensuring that any previously undisclosed side effects of treatment were acknowledged and that the marketing authorization holders were informed accordingly.

Patients completed a semistructured paper-based questionnaire over approximately 20 minutes. The patient survey comprised 35 closed questions (each with 2–12 possible responses) and two “free-text response” questions. The physicians’ questionnaire was completed online in approximately 15 minutes and comprised 24 closed questions (each with 2–9 possible responses; multiple responses were possible for some questions) and five questions that required physicians to estimate the percentage of their patients involved in each case.

Both questionnaires explored elements of MS diagnosis, treatment, and disease management to obtain greater detail on key areas, such as the current needs and future developments of treatment for MS. Research was coordinated by an international health care market research agency, which collated responses from the survey into a wider research database, and conducted detailed analysis to generate qualitative and quantitative outputs.

Results

Demographics

In total, 280 physicians completed the survey (Australia, n = 10; Canada, n = 20; France, n = 50; Germany, n = 50; Italy, n = 50; Spain, n = 50; UK, n = 50). Questionnaires were completed by 331 patients (Australia, n = 30; Canada, n = 51; France, n = 50; Germany, n = 50; Italy, n = 50; Spain, n = 50; UK, n = 50).

Patient involvement in treatment decisions

In total, 58% (161/280) of physicians believed that patients should select their treatment in partnership with their medical team; however, when asked “How involved are your MS patients in the treatment decision-making process?”, only 47% (131/280) of these physicians stated that their patients were fully involved. This proportion varied among countries, with Canada (75%; 15/20) appearing to have the highest level of patient involvement in the decision-making process, followed by the UK (62%; 31/50). This proportion was lowest in Spain, where only 20% (10/50) of physicians stated that their patients were fully involved in the process.

Overall, 23% (77/331) of patients felt that they had discussed treatment options with their medical team, and had themselves been responsible for the selection of their treatment. Canada (53%; 27/51) had the highest proportion of patients selecting their own treatment, followed by the UK (30%; 15/50), Germany (24%; 12/50), France (20%; 10/50), Australia (13%; 4/30), Spain (12%; 6/50), and Italy (6%; 3/50). Twenty-eight percent (93/331) of patients reported that their physician or nurse had selected their treatment without any patient discussion. Regardless of their involvement in the selection of their therapy, most patients (89%; 295/331) reported being aware of both the benefits and possible side effects of their current MS treatment, and being aware of the existence of other MS therapies (84%; 278/331).

Timing of treatment initiation

There were considerable differences between responses from physicians and patients to questions regarding the timing of treatment initiation. The findings from the physician and patient questionnaires regarding time between diagnosis and treatment initiation, by country, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Initiation of disease-modifying drugs (DMDs): patient and physician responses, by country

Physician question:

On average, how long following the diagnosis of MS do you usually start to actively treat a patient with pharmacotherapies/DMDs?

Patient question:

How long following your diagnosis did you start undergoing treatment for your MS?

| Within 2 months | Within 3–6 months | Within 7–12 months | Greater than 12 months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician (%) | Patient (%) | Physician (%) | Patient (%) | Physician (%) | Patient (%) | Physician (%) | Patient (%) | |

| Australia | 80 | 37 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 13 | 10 | 40 |

| Canada | 45 | 31 | 45 | 22 | 10 | 12 | 0 | 35 |

| France | 48 | 42 | 44 | 20 | 2 | 12 | 6 | 26 |

| Germany | 64 | 24 | 32 | 26 | 4 | 10 | 0 | 40 |

| Italy | 56 | 42 | 34 | 30 | 8 | 12 | 2 | 16 |

| Spaina | 38 | 22 | 44 | 16 | 16 | 10 | 2 | 50 |

| UK | 24 | 14 | 44 | 20 | 24 | 18 | 8 | 48 |

| Overall | 47 | 30 | 39 | 21 | 10 | 12 | 4 | 36 |

Notes: 2% of patients responded ‘Don’t know’; n = 331 for total patients; n = 280 for total physicians.

Across all seven countries, 86% (241/280) of physicians responded that, on average, treatment was initiated (pharmacotherapy/DMDs) within 6 months of diagnosis; 4% (10/280) stated that they generally initiated treatment more than 12 months after a diagnosis of MS. Physician response to this question varied across countries, with 96% (48/50) of physicians from Germany reporting that they initiate therapy within 6 months of diagnosis, compared with 68% (34/50) of those from the UK. In contrast, only 51% (169/331) of all patients reported starting treatment within 6 months of their diagnosis. The corresponding proportion from Germany was 50% (25/50) and from the UK 34% (17/50). Furthermore, 36% (120/331) of patients said that their treatment was initiated more than 12 months after diagnosis. Patient responses to this question also varied across countries: Spain had the highest proportion of patients (50%; 25/50) reporting initiating therapy more than 12 months after diagnosis, compared with 16% (8/50) from Italy.

Treatment interruptions and discontinuations

Table 2 provides a summary of patient and physician responses, by country, of treatment breaks and discontinuations.

Table 2.

Summary of treatment interruptions and discontinuations: patient and physician responses, by country

Physician questions:

1. Approximately what percentage, if any, of all your treated MS patients take a treatment break?

2. Approximately what percentage, if any, of all your treated MS patients stop their treatment?

Patient questions:

1. Have you ever taken a break from your MS treatment, ie, where you have actively decided not to take your treatment as opposed to forgetting to take it and which could last 1 day or longer?

2. Have you ever stopped taking your MS treatment?

| Patients taking a break from treatment (mean scores) | Patients discontinuing treatment (mean scores) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician (%) | Patient (%) | Physician (%) | Patient (%) | |

| Australia | 17 | 47 | 12 | 30 |

| Canada | 17 | 37 | 14 | 27 |

| France | 15 | 44 | 10 | 26 |

| Germany | 18 | 16 | 15 | 10 |

| Italy | 20 | 40 | 13 | 18 |

| Spain | 14 | 18 | 12 | 12 |

| UK | 18 | 20 | 17 | 12 |

| Overall | 17 | 31 | 14 | 19 |

Notes: n = 331 for total patients; n = 280 for total physicians.

On average, physicians estimated that approximately 17% of all their treated patients with MS take a break from treatment, and that 14% discontinue treatment altogether. In contrast, 31% of responding patients reported having taken a deliberate break from treatment of 1 day or longer, and 19% reported that they had stopped taking their MS treatment completely. The proportion of patients having taken a break from treatment was highest in Australia (47%; 14/30) and lowest in Germany (16%; 8/50). Almost all physicians in this survey reported having at least one patient who had taken a break from and/or stopped their MS therapy (93%; 260/280 and 98%; 273/280, respectively). More than half of physicians (59%; 166/280) responded “No” to the question “In general, do you find compliance an issue when treating MS patients?”

Physicians who reported having patients taking a break from, or discontinuing, treatment (n = 277) ranked “Side effects (in general)” as the main reason that patients may take a break or stop their MS treatment (82% of respondents), followed by “Disease showing no sign of decline” (54% of respondents; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Main reasons why patients may take a break or stop their MS treatment, as rated by physicians.

Notes: n = 277 (total number of physicians with patients who had taken a break from, or stopped, their MS therapy). ‘Other’ responses not shown because the number of responses was too small.

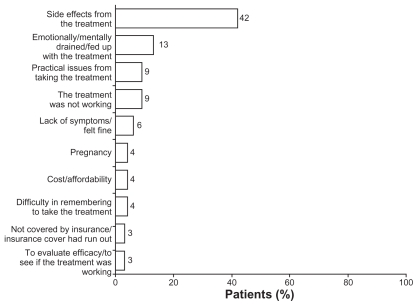

Only 42% of patients who reported taking a treatment break or stopping their treatment (n = 113) cited “Side effects from the treatment” as the main reason for this change, followed by being “Emotionally/mentally drained/fed up with the treatment”, “Practical issues from taking the treatment”, and “The treatment was not working” (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Main reasons for taking a break or stopping their MS treatment, as rated by patients.

Notes: n = 113 (total number of patients who had ever taken a break from or stopped their MS treatment).

Overall, just over half (56%; 187/331) of all patients in this survey reported discussing aspects of their MS treatment other than side effects with their physician or nurse, although this varied considerably across the different countries involved. For example, 84% (42/50) of UK patients reported taking this action compared with 37% (11/30) of Australian respondents.

Discussion

This study was designed to assess physicians’ and patients’ perceptions of the management of MS and their attitudes towards treatment. It is generally accepted that good patient–physician communication can help to maintain a patient’s motivation for, and adherence to, DMD therapy.17 The findings reported in this study suggest that there is often substantial disparity between the views of physicians and those of patients with MS, underlining the need for open communication and cooperation between the patient and the health care team.

There is evidence that the benefits of DMDs are greatest when treatment is started early in the disease course.18 In the majority of countries participating in this survey, treatment with DMDs was initiated within 12 months of MS diagnosis. This finding was not, however, consistent in all instances, and there were differences among countries. This may be due to cultural differences and variations between the health care systems of the countries involved in the survey. Additionally, some physicians advocate a gap of some months between diagnosis and treatment initiation, to allow patients to assimilate the implications of their diagnosis and to accept the need for treatment. Interestingly, there was considerable disparity between the physician and patient responses regarding the proportion of patients waiting over 12 months to initiate treatment, the potential reasons for which are currently unknown.

Although the importance of involving the patient in therapeutic decision making is widely recognized, one in four patients in this study responded that their treatment options had not been discussed with them prior to the selection of a DMD by their medical team. In some cases this may have reflected the preference of patients to allow their physicians to make treatment decisions. Additionally, while it is important for patients to be engaged in the decision-making process, their disease characteristics may, to some extent, dictate which therapy is appropriate.

Our results show that, although nearly all physicians recognized that at least one of their patients had taken a break from medication, the true scale of nonadherence was generally underestimated by physicians, although there was considerable variability between countries in the disparity between physician and patient responses regarding treatment persistence. While the degree to which patients adhere to their medication regimen is difficult to assess and quantify accurately, this study found that gaps in treatment and discontinuation were common, a result that is in line with previous data.14,15,19,20 In this study, the majority of physicians did not find compliance a problem; they felt their patients were able to follow instructions. This, however, would seem to be at odds with the finding of a high proportion of patients taking treatment breaks.

As previously observed,15 AEs were recognized by both patients and physicians as having a negative impact on adherence. There is a need for education programs aimed at increasing both physician and patient awareness of methods for managing AEs associated with DMDs.

Although our study contributes to the understanding of the issues facing patients and their physicians regarding the treatment of MS, certain limitations must be acknowledged. It is difficult to accurately compare the responses of the physicians with those of the patients: the patient population was a general sample from each country, rather than from the same centers as the physicians. This may have affected the finding that patient and physician perceptions differed. Furthermore, the inclusion criteria selected for centers treating relatively high proportions of patients with MS. It is possible that any disconnect between the attitudes of physicians and those of patients may be underestimated as a result – physicians treating fewer patients with MS may be less aware of adherence issues than those who more regularly treat MS. In some cases, the questions asked of the patients were necessarily different from those asked of the physicians, and the two questionnaires were administered in two different formats (one written, one completed online). Additionally, data are not available to determine any disease characteristics that may have led to differences in response. Respondents’ interpretation of some of the terms used in the questionnaires (such as “compliance”, “treatment break”, and “adherence”) may have varied as the terms were not defined in the questionnaires. Furthermore, owing to this being an international survey, the observed differences in responses for some questions may have been a result of regional and national variations in health care provision, such as the availability of certain medications.

At the time of this survey, all available DMDs were administered parenterally. It remains to be seen whether the recent advent of oral therapies for MS will affect rates of treatment adherence, but experience in other therapy areas shows that, as with injectable drugs, adherence to oral therapies tends to be suboptimal.21

In summary, these findings not only support previous suggestions that patient adherence to MS therapy is suboptimal, but also highlight that physicians may underestimate and undervalue the actual levels of adherence among their patients. This underestimation may prevent physicians from accurately assessing the efficacy of the treatment prescribed, which, in turn, could lead to inappropriate treatment escalation in patients who appear to be responding poorly to first-line therapy. Improving the dialogue between patients and health care professionals may support greater adherence to DMD therapy and, ultimately, improve outcomes.

Supplementary materials

Table S1.

Questions included in physicians’ questionnaire

| Physician questions |

|---|

|

Table S2.

Questions included in patients’ questionnaire

| Patient questions |

|---|

|

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Steve Smith and Anna Palagyi of Caudex Medical Ltd, Oxford, UK (supported by Merck Serono S.A. – Geneva, Switzerland, a branch of Merck Serono S.A., Coinsins, Switzerland, an aff iliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), for assistance with the preparation of the initial draft of the manuscript and for collating input from all authors (SS), and for editing for English and assistance with preparation for submission (AP).

Footnotes

Disclosure

This study was commissioned and supported by Merck Serono S.A. – Geneva, Switzerland, a branch of Merck Serono S.A., Coinsins, Switzerland, an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, with research conducted by GfK Healthcare, London, UK. AR and EV are employees of Merck Serono S.A. – Geneva, Switzerland, a branch of Merck Serono S.A., Coinsins, Switzerland, an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. MB and DH are employees of GfK Healthcare, London, UK.

References

- 1.Bennett JL, Stuve O. Update on inflammation, neurodegeneration, and immunoregulation in multiple sclerosis: therapeutic implications. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32:121–132. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181880359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald WI. Relapse, remission, and progression in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1486–1487. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011163432010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray TJ. Diagnosis and treatment of multiple sclerosis. BMJ. 2006;332:525–527. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7540.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Compston A, Confavreux C, Lassmann H. McAlpine’s Multiple Sclerosis. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Confavreux C, Vukusic S, Moreau T, Adeleine P. Relapses and progression of disability in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1430–1438. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011163432001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinshenker BG, Bass B, Rice GP, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study. 1. Clinical course and disability. Brain. 1989;112(Pt 1):133–146. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. [Accessed August 21, 2011]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_report/en/index.html.

- 8.Lugaresi A. Addressing the need for increased adherence to multiple sclerosis therapy: can delivery technology enhance patient motivation. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6:995–1002. doi: 10.1517/17425240903134769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Treadaway K, Cutter G, Salter A, et al. Factors that influence adherence with disease-modifying therapy in MS. J Neurol. 2009;256:568–576. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0096-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halpern R, Agarwal S, Dembek C, Borton L, Lopez-Bresnahan M. Comparison of adherence and persistence among multiple sclerosis patients treated with disease-modifying therapies: a retrospective administrative claims analysis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:73–84. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S15702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan H, Cai Q, Agarwal S, Stephenson JJ, Kamat S. Impact of adherence to disease-modifying therapies on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with multiple sclerosis. Adv Ther. 2011;28:51–61. doi: 10.1007/s12325-010-0093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Sabbagh A, Bennet R, Kozma C, Meletiche D. Medication gaps in disease-modifying therapy for multiple sclerosis are associated with an increased risk of relapse: findings from a national managed care database. J Neurol. 2008;255(Suppl 2):S79. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uitdehaag B, Constantinescu C, Cornelisse P, et al. Impact of exposure to interferon beta-1a on outcomes in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: exploratory analyses from the PRISMS long-term follow-up study. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2011;4:3–14. doi: 10.1177/1756285610391693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tremlett HL, Oger J. Interrupted therapy: stopping and switching of the beta-interferons prescribed for MS. Neurology. 2003;61:551–554. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078885.05053.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Rourke KE, Hutchinson M. Stopping beta-interferon therapy in multiple sclerosis: an analysis of stopping patterns. Mult Scler. 2005;11:46–50. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1131oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. Atlas of MS Database. 2007. [Accessed August 21, 2011]. Available from: http://www.atlasofms.org/query.aspx?pq=yes&s=1&q=3&r=Global&year=2007.

- 17.Tremlett H, Vander Mei I, Pittas F, et al. Adherence to the immuno-modulatory drugs for multiple sclerosis: contrasting factors affect stopping drug and missing doses. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17:565–576. doi: 10.1002/pds.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. MS: the Guide to Treatment and Management. 2008. [Accessed August 21, 2011]. Available from: http://www.msif.org/en/resources/msif_resources/msif_publications/ms_the_guide_to_treatment_and_management/treatments_affecting_longterm_course_of_disease/index.html.

- 19.Portaccio E, Zipoli V, Siracusa G, Sorbi S, Amato MP. Long-term adherence to interferon beta therapy in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol. 2008;59:131–135. doi: 10.1159/000111875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ri J, Porcel J, Tellez N, et al. Factors related with treatment adherence to interferon beta and glatiramer acetate therapy in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11:306–309. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1173oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Questions included in physicians’ questionnaire

| Physician questions |

|---|

|

Table S2.

Questions included in patients’ questionnaire

| Patient questions |

|---|

|