Abstract

Severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) develops in about 25% of patients with acute pancreatitis. Severity of acute pancreatitis is linked to the presence of systemic organ dysfunctions and/or necrotizing pancreatitis. Risk factors independently determining the outcome of SAP are early multiorgan failure (MOF), infection of necrosis, and extended necrosis (>50%). Morbidity of SAP is biphasic, in the first week it is strongly related to systemic inflammatory response syndrome while, sepsis due to infected pancreatic necrosis leading to MOF syndrome occurs in the later course after the first week. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography provides the highest diagnostic accuracy for necrotizing pancreatitis when performed after the first week of disease. Patients who suffer early organ dysfunctions or are at risk for developing a severe disease require early intensive care treatment. Antibiotic prophylaxis has not been shown as an effective preventive treatment. Early enteral feeding is based on a high level of evidence, resulting in a reduction of local and systemic infection. Patients suffering infected necrosis causing clinical sepsis are candidates for intervention. Hospital mortality of SAP after interventional or surgical debridement has decreased to below 20% in high-volume centers.

Keywords: Infected pancreatic necrosis, Severe acute pancreatitis, Necrosectomy

Natural Course of Pancreatitis

There are two phases of acute pancreatitis (AP): the early phase occurs during the first week from the time of onset, and is related to organ failure, secondary to systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Infection is not a feature of the early phase. Proinflammatory cytokines contribute to respiratory, renal, and hepatic failure [1, 2]. The “second or late phase” which starts 14 days after the onset of the disease, is marked by infection of the gland, necrosis and septic systemic complications causing a significant increase in mortality. Infection of the necrotic pancreas occurs in the 8%–12% of the patients with AP and in 30%–40% of patients with necrotizing pancreatitis, and it is considered the most important risk factor of necrotic pancreatitis.

The extent of pancreatic necrosis is not fixed and may progress as the disease evolves during the first 2 weeks. Fluid collections are common and are termed as acute fluid collections before 4 weeks. Fluid collections after 4 weeks are termed as pancreatic pseudocyst. Late phase of AP is characterized by local complications. Infection of pancreatic necrosis occurs in 25–70% of patients with necrotizing pancreatitis and is believed to occur as a result of bacterial translocation due to failure of intestinal barrier [3, 4]. Mortality occurs in two peaks. In the early phase, it is due to severe SIRS and in the late phase due to multiorgan failure (MOF), secondary to infective local complications or systemic sepsis [5, 6].

| Classification |

| Working Group Classification—2007 [6] |

| Interstitial Edematous Pancreatitis |

| Necrotizing Pancreatitis |

| Pancreatic necrosis with peripancreatic necrosis—sterile necrosis, infected necrosis |

| Pancreatic necrosis alone—sterile necrosis, infected necrosis |

| Peripancreatic necrosis alone—sterile necrosis, infected necrosis |

| (<4 weeks after onset of pancreatitis) |

| Acute peripancreatic fluid collection—sterile, infected |

| Acute postnecrotic collection |

| Pancreatic necrosis with peripancreatic necrosis—sterile, infected |

| Pancreatic necrosis alone—sterile, infected |

| Peripancreatic necrosis alone—sterile, infected |

| (>4 weeks after onset of pancreatitis) |

| Pancreatic pseudocyst—sterile, infected |

| Walled-off necrosis |

| Pancreatic necrosis with peripancreatic necrosis—sterile, infected |

| Pancreatic necrosis alone—sterile, infected |

| Peripancreatic necrosis alone—sterile, infected |

Diagnosis

After the diagnosis of AP, it is important to predict the severity of the disease and make a clinical decision whether a particular patient requires intensive care or not. There are various scoring systems (Ranson, Glasgow, APACHE II, SOFA, etc.) that help to stratify the severity of AP. The bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis (BISAP) stratifies patients within the first 24 h of admission according to their risk of in-hospital mortality and is able to identify patients at increased risk of mortality prior to the onset of organ failure. One point is assigned for the presence of each of the following during the first 24 h: blood urea nitrogen >25 mg/dL; impaired mental status; SIRS; age >60 years; or the presence of a pleural effusion (BISAP). Score of > 3 is associated with 5–20% mortality [7]. BISAP score is a simple clinical bedside scoring system.

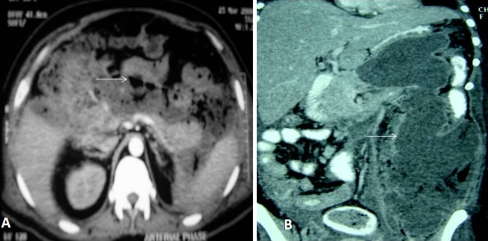

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) is the gold standard in diagnosing pancreatic necrosis. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging is a good alternative in patients with renal failure. The current guidelines recommend that CECT is indicated for patients with persistent organ failure, signs of sepsis, or clinical deterioration 6–10 days after admission [8]. The Balthazar’s CT severity index (CTSI) (Table 1) [9] is commonly used to stratify the severity and also helps predicting mortality. Figure 1 is a CECT scan image of infected pancreatic necrosis (IPN) (A) and necrosis extending into the left paracolic gutter (B). CTSI modified by Mortele et al. [10] differs from the Balthazar’s severity index by the addition of a simplified evaluation of the presence and number of fluid collections and the extent of pancreatic necrosis, and assessment, with different weighting factors, of the presence of extrapancreatic findings such as pleural fluid, ascites, extrapancreatic parenchymal abnormalities (infarction, hemorrhage, or subcapsular fluid collection), vascular complications (venous thrombosis, arterial hemorrhage, or pseudoaneurysm formation), and involvement of the gastrointestinal tract (inflammation, perforation, or intramural fluid collection) [10].

Table 1.

Balthazar’s CTSI

| CT grades | Points |

|---|---|

| (A) Normal pancreas | 0 |

| (B) Edematous pancreatitis | 1 |

| (C) B plus mild extrapancreatic changes | 2 |

| (D) Severe extrapancreatic changes including one fluid collection | 3 |

| (E) Multiple or extensive extrapancreatic collections | 4 |

| Necrosis | |

| None | 0 |

| Less than one-third | 2 |

| Greater than one-third or less than one-half | 4 |

| Greater than one-half | 6 |

| CT severity index (CT grade + necrosis score) | |

| Severity index | Complications |

| 0–3 | 8% |

| 4–6 | 35% |

| 7–10 | 92% |

| Deaths | |

| 0–3 | 3% |

| 4–6 | 6% |

| 7–10 | 17% |

Fig. 1.

a CECT scan of abdomen showing >50% pancreatic necrosis with extensive air pockets (white arrow) suggestive of IPN (Balthazar’s CTSI score—10). b CECT scan of abdomen showing pancreatic necrosis extending into left paracolic gutter (white arrow)

Role of Fine Needle Aspiration FNA

IPN is diagnosed by image-guided FNA for gram staining and/or bacterial culture. Gas in the necrosis on CT scan raises the suspicion of IPN, and surgery may be indicated even without FNA [11, 12]. As the surgical intervention should be delayed as long as possible or even avoided completely with the judicious use of radiological drainage, the results of FNA may not alter the patient management.

Indications for Surgery

IPN

Massive hemorrhage

Bowel perforation

Symptomatic organized necrosis

Sterile necrosis with clinical deterioration

Timing of Surgery

Surgery earlier than 14 days after onset of the disease is not recommended in patients with necrotizing pancreatitis unless there are specific indications, such as MOF, which do not improve despite maximal therapy, and in those who develop abdominal compartment syndrome [13]. The current concept for timing of intervention is that it should be undertaken as late as possible after disease onset (>4 weeks), when the necrotic process has stopped extending, there is clear demarcation between viable and nonviable tissues and when the infected necrosis has become walled off or organized. Such a delay helps decreasing the risk of bleeding [14, 15].

Nutrition

Enteral nutrition starting in the early phase of severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) is superior to total parenteral nutrition unless paralytic ileus is present [16]. Tube feeding is possible in the majority of patients, but may need to be supplemented by the parenteral route [17]. Continuous tube feeding with peptide-based formulae is possible in the majority of patients; the jejunal route is recommended if gastric feeding is not tolerated [17]. In SAP, it is also possible to combine total parenteral nutrition and enteral nutrition when adequate caloric support cannot be obtained by the enteral route alone [17].

Role of Antibiotics

The use of prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics reduces infection rates in CT-proven necrotizing pancreatitis, but may not improve survival [13]. However, broad-spectrum antibiotics with good tissue penetration are necessary to prevent infection in SAP [16]. Commonly used antibiotics are carbapenems, quinolones, and third-generation cephalosporins. How long the antibiotics should be given is a debate, although they are generally continued for 2 weeks. Prolonged antibiotic therapy for >4 weeks increases the prevalence of fungal infections [18]. The role of prophylactic antifungal agents has not been fully defined.

Two randomized double-blinded prospective controlled multicenter trials proved antibiotic prophylaxis ineffective in regard to reduction of infection of necrosis and hospital mortality [18, 19]. A Cochrane meta-analysis concluded that antibiotic prophylaxis is not protective in SAP [20].

Timing of Cholecystectomy

Optimal timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with acute biliary pancreatitis (ABP) is still contentious. In mild ABP, laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been considered the definitive treatment [21]. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be performed as soon as the serum amylase decreases and symptoms improve [22]. Heinrich et al. [23] analyzed four prospective trials evaluating the optimal timing for surgery and concluded that early laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be preferred in patients with mild to moderate ABP, whereas in patients with severe ABP, who did not undergo surgery for necrotizing pancreatitis, cholecystectomy appears to be favorable after full recovery [22–26].

Role of ERCP in Biliary Pancreatitis

The benefits of ERCP with endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) has been studied in 3 randomized trials [27–29] and 2 meta-analyses [30, 31]. Patients with predicted mild ABP in the absence of cholangitis have not shown benefits from an early ERCP. The decision on management of patients with predicted severe ABP is still debatable. The United Kingdom guidelines recommend that urgent therapeutic ERCP should be performed within 72 h of admission in all patients with predicted severe ABP, whether or not cholangitis is present [8].

However, a recent meta-analysis by Petrov et al. [32] demonstrated that early ERCP with or without ES had no beneficial effects in patients with predicted mild or severe ABP without cholangitis. The conclusion of this study was partially supported by the 2007 guidelines of the American Gastroenterology Association, which stated that early ERCP in patients with severe ABP without signs of acute cholangitis is still not uniformly accepted in the literature [33].

Management of Sterile Pancreatic Necrosis

Patients with sterile pancreatic necrosis should be managed conservatively and undergo intervention only in selected cases, such as those patients with MOF who do not improve despite maximal therapy in the intensive care unit [13].

Management of IPN

Surgery is the gold standard treatment for IPN. The current recommendation is to delay the surgery for 4 weeks after the onset of pancreatitis. This may lead to prolonged use of antibiotics causing more antibiotic resistance and secondary fungal infections [34].

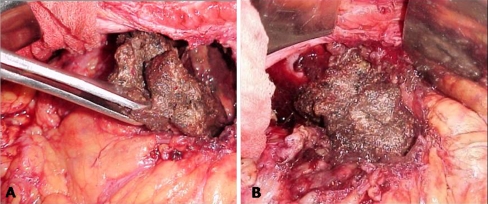

There are various approaches to remove the pancreatic necrosum. Table 2 outlines various strategies for necrosectomy. Figure 2 shows the technique of open pancreatic necrosectomy.

Table 2.

Strategies for necrosectomy

| Open approach: |

| a. Open necrosectomy with closed packing |

| b. Open necrosectomy with open packing |

| c. Open necrosectomy with continous postoperative lavage |

| d. Programmed open necrosectomy |

| Minimal invasive techniques: |

| A. Endoscopic techniques: |

| a. NOTES |

| b. Necrosectomy through PEG |

| c. Sinus tract endoscopy |

| B. Laparoscopic techniques: |

| a. VARD |

| b. Single-port laparoscopic necrosectomy |

| c. Retrogastric approach |

| d. Transgastric approach |

| e. Transmesocolic approach |

| f. Hand-assisted laparoscopic necrosectomy |

| C. Radiological techniques: |

| a. Transperitoneal drainage |

| b. Retroperitoneal drainage |

| c. Transmural drainage—stomach, duodenum |

| D. Step-up approach: |

| a. Radiological drainage |

| b. Minimal invasive surgery |

| c. Open surgery |

NOTES natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery, VARD video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative image of open pancreatic necrosectomy (a and b)

Open necrosectomy with closed packing—after the removal of necrotic tissue, the cavity is filled with penrose drains via various stab incisions. Between two and twelve drains are placed. The intention of drains is to provide compression rather than facilitate external drainage. The drains are removed one every other day, starting 5–7 days postoperatively.

Open necrosectomy with open packing—after removal of necrotic tissue the necrotic cavity is packed; drains placed in pancreatic bed and the incision is left open. This technique is associated with increased incidence of fistulae, bleeding, and incisional hernia.

Open necrosectomy with continous postoperative lavage—the procedure is based on insertion of 2 or more double 20–24 French drains and a single lumen 28–38 French silicone rubber on each side of the abdomen and placed with the tip at the tail of the pancreas. The smaller lumen of the drains is used for the inflow of the lavage and the larger lumen for the outflow. At least 10–30 L lavage is required in the first few days. Drains can be removed after 2–3 weeks.

Programmed open necrosectomy—debridement and removal of necrotic tissue is done over multiple procedures. After necrosectomy, the pancreatic bed is packed with sponges and soft drains are placed on the top of the packs. The abdomen is closed with zipper.

Successful necrosectomy can be performed by using blunt dissection, avoiding removal of adherent material, avoiding division of strands running across the cavity, using repeated saline flushes to separate the necrosum, and use of packs to control massive bleeding. An ileostomy may be considered when there is necrosis extending in the paracolic gutter.

Minimally Invasive Necrosectomy

Recognition that laparotomy may itself add to morbidity by increasing postoperative organ dysfunction has led to the development of alternative methods for debridement. These alternative methods mostly involve debridement via retroperitoneal, laparoscopic, or endoscopic approaches or combinations of these. They share the common goal of avoiding laparotomy and are collectively referred to as minimally invasive necrosectomy (MIN). To date, there is no randomized trial evidence comparing these techniques with traditional ‘open’ necrosectomy or, equally importantly, comparing the different techniques of MIN against one another.

Endoscopic necrosectomy—the necrosectomy can be done through the natural orifices [35] and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). Endosopic ultrasound is done to localize the necrotic cavity. The posterior wall of stomach is punctured with the needle, the tract is dilated. Necrosectomy is carried out with different devices, i.e., snares, baskets, forceps [36, 37]. The necrosectomy is followed by copious irrigation with normal saline solution. For lavage and drainage, a 7 Fr nasocystic and 10 Fr pig tail drains are placed in the cavity. Multiple sessions are required for complete necrosectomy. Recent data from the literature indicated that the endoscopic approach could be a safe and effective modality for management of IPN with potentially lower morbidity than the traditional surgical approach. However, the data is from small prospective studies and multicenter prospective randomized trials are needed to clarify the role of the endoscopic approach in necrotising pancreatitis. A similar procedure can be carried out via PEG [38].

Radiological necrosectomy—percutaneous catheter drainage may be used as a primary treatment for pancreatic necrosis, as a secondary treatment to manage postoperative fluid collection or to delay the definitive treatment. Most of the collections are located in the lesser sac. These collections can be reached through various routes; for example, transperitoneal, retroperitoneal, and transmural. The catheters have multiple holes and minimal diameter of 12–14 Fr.[39]. Percutaneous drainage of collections may help drain the pus, decrease the systemic sepsis, and delay the necrosectomy.

Laparoscopic Necrosectomy—most of the laparoscopic techniques use either the anterior or lateral approach. Video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement (VARD) is a technique that uses the lateral approach. Radiologically guided drain is initially placed in the necrotic cavity. The patient is placed in a supine position with his left flank elevated. A subcostal or intercostal incision is made to follow the retroperitoneal drains up to the necrotic area, which is opened bluntly through digital examination. Necrotic tissue is debrided by forceps and a suction device. A 10-mm laparoscope and a long 10-mm trocar are inserted through the retroperitoneal wound. Under laparoscopic vision, the remaining necrotic tissue is removed by laparoscopic graspers. Two surgical drains are inserted into the necrotic cavity via the incision [40–42]. In addition to its minimal invasive nature, VARD avoids peritoneal contamination. The disadvantages of VARD are as follows: it requires repeated sessions, colonic complications cannot be assessed, and performing cholecystectomy is impossible. Necrosectomy can also be done through anterior approach. The routes used are retrogastric retrocolic and transmesocolic. Anterior approach can also be used for hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery [43]. There are few recent reports of single-port laparoscopic necrosectomy [44].

As MIN techniques have been available for a decade, it is perhaps not surprising that there is a reasonable degree of concordance regarding each type of procedure. It is accepted that technology and techniques will continue to evolve, however, in order to maintain a fair perspective, it should be noted that the ‘conventional’ operation of open necrosectomy has also evolved and been simplified and, in specialist hepatopancreaticobiliary centers, is carried out with very low mortality [45, 46]. In order to maintain a balanced perspective, however, it should be acknowledged that the available data for the minimally invasive approaches do suggest that good outcomes can be achieved. The traditional limitations of open surgery (worsening of organ dysfunction and postoperative need for critical care) should be balanced against the limited information on the outcomes of the minimally invasive approaches. Of the minimally invasive techniques, the retroperitoneal approach may be selected in patients with left-sided, predominantly retroperitoneal necrosis with a semisolid collection. Endoscopic necrosectomy appears most effective in addressing a unilocular collection containing fluid of low Hounsfield unit density and located in a principally retrogastric position. Similarly, laparoscopic necrosectomy seems to be most effective in addressing unilocular, retrogastric fluid collections, but has the additional advantage of allowing for a wide cystogastrostomy and perhaps better debridement than with endoscopy.

Step-up vs Step-down Approach

In step-up approach the initial treatment is radiological drainage. If this fails then minimal invasive surgery is employed, and open surgery is reserved for those patients who do not respond to less invasive techniques. In step-down approach open surgery is used as the primary treatment and less invasive techniques are used to manage subsequent collections or ongoing necrosis. These both the approaches are compared in the PANTER trial (Pancreatitis, Necrosectomy versus step-up approach). The trial concluded that the minimally invasive step-up approach, as compared with open necrosectomy, reduced the rate of the composite end point of major complications or death among patients with necrotizing pancreatitis [47].

Complications of Necrosectomy

Complications following necrosectomy remain common; however, recent data have shown that the overall morbidity and mortality have declined. These complications include pancreatic fistula, enterocutaneous fistula, colonic strictures, intestinal obstruction, secondary infections, wound infection, dehiscence, and incisional hernia [48]. Bleeding is a rare complication usually managed by topical hemostatic agents, suturing, packing, and angioembolization. Fistulae occur in up to 30% of patients undergoing laparotomy, and initially it should be managed conservatively, with surgical repair deferred until such time as the pancreatitis has resolved completely [48]. Colonic complications in the form of perforation or strictures are not uncommon. Patients with extensive necrosis extending in the left paracolic gutter are more prone to these complications. A defunctioning ileostomy followed by resection with primary anastomosis later may be required in these patients. Wound infection and dehiscence must be treated more aggressively. Endocrine and exocrine insufficiencies of the pancreas are also relatively common [48].

Summary

Management of acute necrotizing pancreatitis has changed significantly over the past years. Early management is nonsurgical and solely supportive. Today, more patients survive the early phase of severe pancreatitis due to improvements in intensive care medicine. It is clear that although the era of MIN has arrived, there is a limited body of evidence. The selection of treatment must be guided by the need to ensure the availability of true multidisciplinary expertise in a specialist unit. Techniques should not be selected simply because of the expertise of an individual clinician.

References

- 1.Folch-Puy E. Importance of the liver in systemic complications associated with acute pancreatitis: the role of kuffer cells. J Pathol. 2007;211:383–388. doi: 10.1002/path.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatia M, Brady M, Shokuchi S, Christmas S, Neoptolemas JP, Slavin J. Inflammatory mediators in acute pancreatitis. J Pathol. 2000;190:117–125. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200002)190:2<117::AID-PATH494>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beger HG, Rau B, Mayer J, Pralle U. Natural course of acute pancreatitis. World J Surg. 1997;21:130–135. doi: 10.1007/s002689900204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchler MW, Gloor B, Muller CA, Friess H, Seiler CA, Uhl W. Acute necrotising pancreatitis: treatment strategy according to the status of infection. Ann Surg. 2000;232:619–626. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200011000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besselink MG, Santvoort HC, Boermeester MA, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Goor H, et al. Dutch Acute Pancreatitis Study Group. Timing and impact of infections in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2009;96:267–273. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group (2008) Revision of the Atlanta Classification of Acute Pancreatitis. Available at http:www.pancreasclub.com/resources/Atlantaclassification.pdf. Volume 2009

- 7.Wu BU, Johannes RS, Sun X, Tabak Y, Conwell DL, Banks PA. The early prediction of mortality in acute pancreatitis: a large population-based study. Gut. 2008;57:1698–1703. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.152702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Working party of the British society of Gastroenetrology. Association of surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland. Pancreatic society of Great Britain and Ireland. association of Upper GI Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54(Suppl 3):iii1–iii9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.057026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balthazar EJ. Acute pancreatitis: assessment of severity with clinical and CT evaluation. Radiology. 2002;223:603–613. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2233010680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mortele KJ, Wiesner W, Intriere L, Shankar S, Zou KH, Kalantari BN, et al. A modified CT severity index for evaluating acute pancreatitis: improved correlation with patient outcome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1261–1265. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.5.1831261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pappas TN. Computerized tomographic aspiration of infected pancreatic necrosis: the opinion against its routine use. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2373–2374. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00328_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dambrauskas Z, Gulbinas A, Pundzius J, Barauskas G. Value of routine clinical tests kin predicting the development of infected pancreatic necrosis in severe acute pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:1256–1264. doi: 10.1080/00365520701391613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uhl W, Warshaw A, Imrie C, Bassi C, McKay CJ, Lankisch PG, International Association of Pancreatology et al. IAP guidelines for the surgical management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2002;2:565–573. doi: 10.1159/000071269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banks PA, Freeman ML, Practice parameters committee of the American College of Gastroenterology Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2379–2400. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uhl W, Warshaw A, Imrie C, Bassi C, Mckay CJ, Lankisch PG, et al. International Association of Pancreatology. IAP Guidelines for the surgical management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2:565–573 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Takeda K, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Hirata K, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, et al. JPN Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: medical management of acute pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:42–47. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-1050-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meier R, Ockenga J, Pertkiewicz M, Pap A, Milinic N, Macfie J, DGEM (German Society for Nutritional Medicine) Löser C, Keim V, ESPEN (European Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition) ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition: pancreas. Clin Nutr. 2006;25:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kochhar R, Ahammed SK, Chakrabarti A, Ray P, Sinha SK, Dutta U, et al. Prevalence and outcome of fungal infection in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:743–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isenmann R, Rünzi M, Kron M, Kahl S, Kraus D, Jung N, et al. Prophylactic antibiotic treatment in patients with predicted severe acute pancreatitis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:997–1004. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dellinger EP, Tellado JM, Soto NE, Ashley SW, Barie PS, et al. Early antibiotic treatment for severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Surg. 2007;245:674–683. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000250414.09255.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Villatoro E, Bassi C, Larvin M (2006) Antibiotic therapy for prophylaxis against infection of pancreatic necrosis in acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD002941 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Taylor E, Wong C. The optimal timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in mild gallstone pancreatitis. Am Surg. 2004;70:971–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinrich S, Schäfer M, Rousson V, Clavien PA. Evidence based treatment of acute pancreatitis: a look at established paradigms. Ann Surg. 2006;243:154–168. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197334.58374.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uhl W, Müller CA, Krähenbühl L, Schmid SW, Schölzel S, Büchler MW. Acute gallstone pancreatitis: timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in mild and severe disease. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:1070–1076. doi: 10.1007/s004649901175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schachter P, Peleg T, Cohen O. Interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the management of acute biliary pancreatitis. HPB Surg. 2000;11:319–322. doi: 10.1155/2000/40290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tate JJ, Lau WY, Li AK. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for biliary pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1994;81:720–722. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schietroma M, Carlei F, Lezoche E, Rossi M, Liakos CH, Mattucci S, et al. Acute biliary pancreatitis: staging and management. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:988–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oría A, Cimmino D, Ocampo C, Silva W, Kohan G, Zandalazini H, et al. Early endoscopic intervention versus early conservative management in patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis and biliopancreatic obstruction: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2007;245:10–17. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000232539.88254.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fölsch UR, Nitsche R, Lüdtke R, Hilgers RA, Creutzfeldt W. Early ERCP and papillotomy compared with conservative treatment for acute biliary pancreatitis. The German Study Group on Acute Biliary Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:237–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701233360401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neoptolemos JP, Carr-Locke DL, London NJ, Bailey IA, James D, et al. Controlled trial of urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic sphincterotomy versus conservative treatment for acute pancreatitis due to gallstones. Lancet. 1988;2:979–983. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)90740-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma VK, Howden CW. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of endoscopic retrograde cholangiography and endoscopic sphincterotomy for the treatment of acute biliary pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3211–3214. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petrov MS, Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Heijden GJ, Erpecum KJ, Gooszen HG. Early endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography versus conservative management in acute biliary pancreatitis without cholangitis: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Ann Surg. 2008;247:250–257. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815edddd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forsmark CE, Baillie J. AGA Institute technical review on acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2022–2044. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waele JJ, Vogelaers D, Blot S, Colardyn F. Fungal infections in patients with severe acute pancreatitis and the use of prophylactic therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:208–221. doi: 10.1086/375603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedland S, Kaltenbach T, Sugimoto M, Soetikno R. Endoscopic necrosectomy of organised pancreatic necrosis: a currently practised NOTES procedure. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:266–269. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baron TH, Thaggard WG, Morgan DE, Stanley RJ. Endoscopic therapy for organised pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:755–764. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8780582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seewald S, Groth S, Omar S, Imazu H, Seitz U, Weerth A, et al. Aggressive endoscopic therapy for pancreatic necrosis and pancreatic abscess: a new safe and effective treatment algorithm. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:92–100. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(05)00541-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baron TH, Morgan DE. Endoscopic transgastric irrigation tube placement via PEG for debridement of organised pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:574–577. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(99)70089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrucci JT, 3rd, Mueller PR. Interventional approach to pancreatic fluid collections. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41:1217–1226. doi: 10.1016/S0033-8389(03)00123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Connor S, Ghaneh P, Raraty M, Sutton R, Rosso E, Garvey CJ, et al. Minimally invasive retroperitoneal pancreatic necrosectomy. Dig Surg. 2003;20:270–277. doi: 10.1159/000071184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Risse O, Auguste T, Delannoy P, Cardin N, Bricault I, Létoublon C. Percutaneous video-assisted necrosectomy for infected pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28:868–871. doi: 10.1016/S0399-8320(04)95150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheung MT, Ho CN, Siu KW, Kwok PC. Percutaneous drainage and necrosectomy in the management of pancreatic necrosis. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:204–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parekh D. Laparoscopic assisted pancreatic necrosectomy: a new surgical option for treatment of severe necrotising pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 2006;141:895–902. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.9.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bucher P, Pugin F, Morel P. Minimally invasive necrosectomy for infected necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2008;36:113–319. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181514c9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruben Rodriguez J, Razo AO, Targarona J, Thayer SP, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL, et al. Debridement and closed packing for sterile or infected necrotizing pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2008;247:294–299. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815b6976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Babu BI, Sheen AJ, Lee SH, O'Shea S, Eddleston JM, Siriwardena AK. Open pancreatic necrosectomy in the multidisciplinary management of postinflammatory necrosis. Ann Surg. 2010;251:783–786. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b59303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, et al. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491–1502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Connor S, Alexakis N, Raraty MG, Ghaneh P, Evans J, Hughes M, et al. Early and late complications after pancreatic necrosectomy. Surgery. 2005;137:499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]