Abstract

Nicotine conjugate vaccine efficacy is limited by the concentration of nicotine-specific antibodies that can be reliably generated in serum. Previous studies suggest that the concurrent use of 2 structurally distinct nicotine immunogens in rats can generate additive antibody responses by stimulating distinct B cell populations. In the current study we investigated whether it is possible to identify a third immunologically distinct nicotine immunogen. The new 1′-SNic immunogen (2S)-N,N′-(disulfanediyldiethane-2,1-diyl)bis[4-(2-pyridin-3-ylpyrrolidin-1-yl)butanamide] conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) differed from the existing immunogens 3′-AmNic-rEPA and 6-CMUNic-BSA in linker position, linker composition, conjugation chemistry, and carrier protein. Vaccination of rats with 1′-SNic-KLH elicited high concentrations of high affinity nicotine-specific antibodies. The antibodies produced in response to 1′-SNic-KLH did not appreciably cross-react in ELISA with either 3′-AmNic-rEPA or 6-CMUNic-BSA or vice-versa, showing that the B cell populations activated by each of these nicotine immunogens were non-overlapping and distinct. Nicotine retention in serum was increased and nicotine distribution to brain substantially reduced in rats vaccinated with 1′-SNic-KLH compared to controls. Effects of 1′-SNic-KLH on nicotine distribution were comparable to those of 3′-AmNic-rEPA which has progressed to late stage clinical trials as an adjunct to smoking cessation. These data show that it is possible to design multiple immunogens from a small molecule such as nicotine which elicit independent immune responses. This approach could be applicable to other addiction vaccines or small molecule targets as well.

Keywords: nicotine, immunotherapy, addiction, vaccine, immunogenicity

1. Introduction

Addictions to tobacco, alcohol and illicit drugs account for nearly 25% of preventable deaths in the U.S. and an increasing proportion worldwide. Available addiction treatment medications, although helpful, have limited efficacy and the potential for side effects in part because the brain pathways they target also mediate normal functions such as memory, learning and reward. Addiction vaccines are being studied as a treatment strategy which targets the drug rather than effector systems in the brain [1]. Vaccines stimulate the production of drug-specific antibodies which bind drug in serum and extracellular fluid and reduce or slow its distribution to brain [2]. Efficacy in blocking addiction-like behaviors in animals has been shown for vaccines directed against nicotine, cocaine, and heroin [3–5]. Nicotine and cocaine vaccines have shown preliminary indications of efficacy in early phase clinical trials without any important side effects [6, 7]. However several nicotine vaccines have recently failed to significantly enhance smoking cessation rates in larger phase II or III clinical trials [8](personal communication Rafaat Fahim, Nabi Biopharmaceuticals).

The major limitation to nicotine vaccine efficacy is that the ability of these vaccines to modify smoking behavior is highly dependent upon the serum antibody concentration achieved. In a Phase II clinical trial, serum nicotine-specific antibody concentrations were highly variable and vaccine efficacy was entirely attributable to the 30% of subjects with the highest serum antibody concentrations [6]. A similar dependence on serum drug-specific antibody concentration was seen in a cocaine vaccine clinical trial [7]. The success of this promising approach to addiction treatment rests upon reliably achieving a robust immunological response to vaccination with high serum antibody concentrations, a result which has been difficult to achieve with existing vaccines.

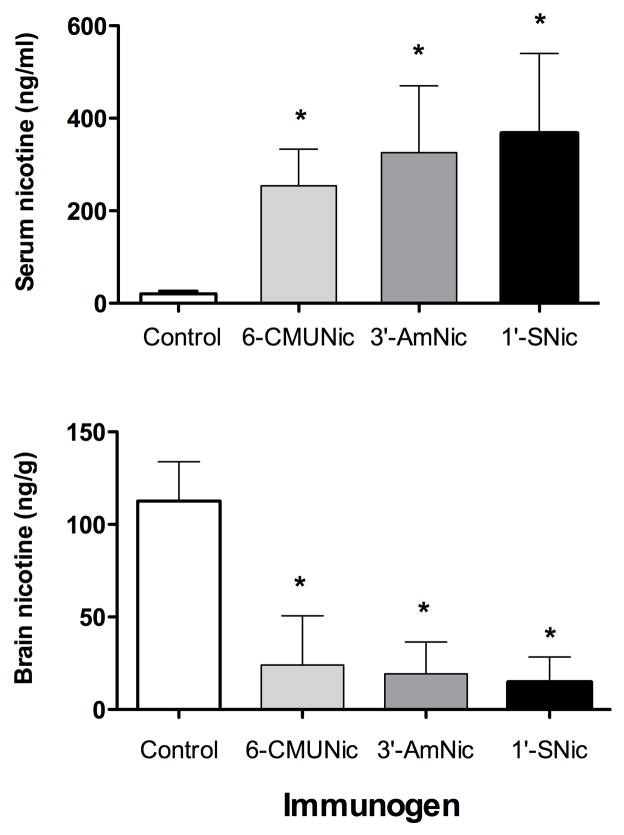

Addictive drugs are small molecules which do not by themselves elicit an immune response, but can be rendered immunogenic by conjugation to a foreign carrier protein through a short (generally 5–15 atom) linker. The resulting immunogen is then mixed with an adjuvant to form the complete vaccine. Various approaches have been used to enhance nicotine vaccine immunogenicity. Improvements have been reported in animals through modifications of hapten structure [9], linker position on the drug [10], linker composition [11, 12], conjugation chemistry [13, 14], type of carrier protein [4, 15], and adjuvant [16]. An alternative approach is to simultaneously administer 2 structurally distinct nicotine hapten-protein conjugate vaccines to provide an additive effect by eliciting distinct immunological responses [17]. The two immunogens used haptens which differed in linker position (Fig 1; 3′-AmNic, 6-CMUNic) so that they presented different aspects of the nicotine molecule for immune recognition. They also differed in linker composition and carrier protein, which may have further altered the epitopes presented. Each individual immunogen elicited antibodies which did not appreciably cross react with the other immunogen, showing that they had activated separate populations of B cells. When the two immunogens were administered to rats together, as a combination (bivalent) vaccine, the resulting serum antibody concentrations were additive and there was a significant correlation between higher total serum antibody concentrations and a greater reduction of nicotine distribution to brain.

Figure 1.

Nicotine and hapten structures. The 1′-SNic disulfide dimer was reduced to monomer prior to conjugation.

In principle it should be possible to administer more than 2 nicotine vaccines at the same time to enhance the immune response even further. However nicotine is a small molecule and it is not clear whether further modification of immunogen design would produce a sufficiently distinctive molecular orientation to serve as a unique epitope and result in a clonally distinct B cell response. We report here the design and synthesis of a novel nicotine immunogen (1′-SNic-KLH) differing from either of those used in the previously reported bivalent vaccine in its linker position, linker composition, conjugation chemistry and carrier protein. We reasoned that altering each of these key components of the conjugate would maximize its ability to function as a distinct nicotine immunogen. Antibodies generated by vaccination with the new immunogen were characterized with regard to their affinity and specificity for nicotine, serum titer and concentration, and ability to retain nicotine in serum and reduce its distribution to brain. The epitope recognition specificity of antibodies generated by the 1′-SNic, 3′-AmNic and 6-CMUNic conjugates were evaluated by measuring their ELISA cross-reactivity when using the other 2 immunogens as the solid phase coating antigen.

2. Material and Methods

2. 1 Synthesis of (2S)-N,N′-(Disulfanediyldiethane-2,1-diyl)bis[4-(2-pyridin-3-ylpyrrolidin-1yl)butanamide] (1′-SNic)

(2S)-4-(2-Pyridin-3-ylpyrrolidin-1-yl)-N-[2-(tritylsulfanyl)ethyl]butanamide

Triethylamine (0.31 g, 3.12 mmol) was added to a solution of lithium (2S)-2-(3-pyridinyl)-1-pyrrolidine butanoate (1) [12] (0.25 g, 1.04 mmol), benzotriazole-1-yl-oxy-tris-(dimethylamino)-phosphonium hexafluorophosphate (0.69 g, 1.56 mmol), and 2-[(triphenylmethyl)sulfanyl]ethan-1-amine hydrochloride [18] (0.56 g, 1.56 mmol) in THF (30 mL).(Scheme 1) The reaction was allowed to stir at room temperature for 2 h under nitrogen. A saturated solution of NaHCO3 (75 mL) was added, and the suspension was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 75 mL). The organic extracts were combined, dried (MgSO4), and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a pale yellow oil. The oil was purified on silica using medium pressure column chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH/NH4OH, 90:9:1) to afford (2S)-4-(2-pyridin-3-ylpyrrolidin-1-yl)-N-[2-(tritylsulfanyl)-ethyl]butanamide (2, 0.28 g, 50%) as a yellow oil. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ1.69 (m, 2 H), 1.86–2.46 (m, 10 H), 2.60 (d, 1H, J = 9 Hz), 3.03 (m, 2 H), 3.36 (m, 2 H), 6.03 (br-s, 1 H), 7.17–7.68 (m, 16 H), 7.65 (d, 1 H, J = 9 Hz), 8.45 (d, 1H, J = 6 Hz), 8.52 (s, 1H). [α]22D −24 (c 0.24, MeOH).

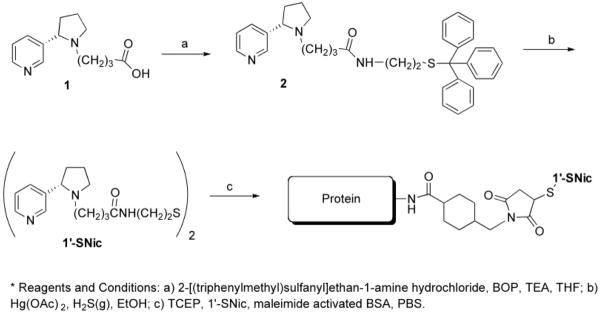

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 1′-SNic and conjugation to the carrier protein. a) 2-[(triphenylmethyl)sulfanyl]ethan-1-amine hydrochloride, BOP, TEA, THF; b) Hg(OAc) 2, H2S(g), EtOH; c) TCEP, 1′-SNic, maleimide activated BSA, PBS.

(2S)-N,N′-(Disulfanediyldiethane-2,1-diyl)bis[4-(2-pyridin-3-ylpyrrolidin-1yl)butanamide] [1′-SNic] dihydrochloride

Mercuric acetate (0.072 g, 0.23 mmol) was added to a solution of (2S)-4-(2-pyridin-3-ylpyrrolidin-1-yl)-N-[2-(tritylsulfanyl)ethyl]butanamide (2, 0.05 g, 0.09 mmol) in EtOH (20 mL) and allowed to stir for 2 h at room temperature.(Scheme 1) H2S gas was then bubbled through the solution, forming a black precipitate. The mixture was filtered, and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a dark oil. The oil was then purified using medium pressure column chromatography on silica (CHCl3/MeOH/NH4OH, 90:9:1) to afford a viscous oil. The oil was dissolved in ethyl acetate (5 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. A 1.0M ethereal solution of HCl (1 mL) was added, and the mixture was evaporated to dryness yielding (2S)-N,N′-(disulfanediyldiethane-2,1-diyl)bis[4-(2-pyridin-3-ylpyrrolidin-1yl)butanamide] dihydro-chloride (1′-SNic, 0.018 g, 68%) as a tan semisolid. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, free base) δ1.67–2.05 (m, 6 H), 2.05–2.24 (m, 4 H), 2.45 (m, 1H), 2.74 (m, 2 H), 3.26–3.48 (m, 4 H), 6.61 (br-s, 1 H), 7.25 (m, 1 H), 7.65 (d, 1 H, J = 9 Hz), 8.45 (d, 1H, J = 6 Hz), 8.56 (s, 1H). LRMS (ESI) m/z 585.3 (M+1). [α]22D +16 (c 0.085, MeOH).

2. 2 Immunogens

Conjugation of 1′-SNic hapten to maleimide-activated BSA

Maleimide-activated BSA (2 mg, ThermoFisher Scientific) was reconstituted in 0.5 mL of distilled water and 1.5 mL of PBS saline buffer (pH 7.2) to give a 1.0 mg/mL working protein stock solution (0.014 mM). A 1′-SNic hapten stock solution (11.48 mM) was prepared using de-gassed PBS saline buffer to which was added the reducing agent, tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP HCl, 15 mM). (Scheme 1) The maleimide-activated BSA stock solution (1.8 mL) was transferred into a sterile cryogenic vial and added to 1′-SNic hapten stock solution with the number of equivalents ranging from 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 50, 75, and 100 moles of 1′-SNic per mole of BSA. The reaction mixture was purged with N2 and incubated at ambient temperature for 2 h under N2 with occasional stirring. After 2 h, the reaction vials were sealed and kept at −20°C. Conjugate solutions were passed through a PD-10 column, eluted with 0.01 M phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4) and stored at 4 °C.

Conjugation of 1′-SNic hapten to maleimide-activated KLH

Maleimide-activated KLH (4 mg, ThermoFisher Scientific) was reconstituted in 0.4 mL of distilled water and 3.6 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.3, 50 mM) to give a 1.0 mg/mL working protein stock solution (0.122 μM). This solution was transferred into a sterile cryogenic vial and combined with 150–4000 equivalents of 1′-SNic hapten stock solution (11.46 mM) that was freshly prepared using a degassed reaction buffer having 15 mM TCEP•HCl as a reducing agent (Scheme 1). The reaction mixture was purged with N2 and incubated at ambient temperature for 2 h under N2 with occasional stirring. After 2 h, the reaction vials were sealed and kept ice-cold.

Activation of native OVA using sulfo-SMCC and conjugation of maleimide-activated OVA to 1′-SNic hapten

Non-activated, native OVA (2 mg, ThermoFisher Scientific) was reconstituted in 0.2 mL of distilled water and 1.8 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.3, 50 mM) to give a 1.0-mg/mL working protein stock solution (0.022 mM). An 11.46 mM sulfo-SMCC (2.0 mg, ThermoFisher Scientific) stock solution was prepared by using the reaction buffer and added (1:50, protein to sulfo-SMCC) to the working protein solution. After stirring the reaction mixture for 1 h at room temperature, the reaction mixture was dialyzed overnight at 0–4 °C using a dialysis cassette (10k MWCO) and the protein solution was added with a freshly prepared 1′-SNic hapten stock solution (11.46 mM) in de-gassed reaction buffer having TCEP HCl (15 mM) as a reducing agent. 1′-SNic hapten stock solution ranging from 25–100 molar equivalents in 25 eq. increments was added to the activated protein. The reaction mixture was purged with N2 and incubated at room temperature for 2 h under a N2 blanket with occasional stirring. After 2 h the reaction mixture was normalized for constant protein concentrations to correct for fluid shifts and kept ice-cold.

3′-Aminomethyl nicotine

(3′-AmNic) was synthesized and conjugated to recombinant Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoprotein A (rEPA) as previously described through a succinic acid linker using carbodiimide to form the complete immunogen 3′-AmNic-rEPA [19]. This immunogen has been extensively studied in rats and reliably produces high concentrations of high affinity (Kd = 11 nM) nicotine-specific antibodies with <1% cross-reactivity to the major nicotine metabolites cotinine and nicotine-N-oxide, the endogenous nicotinic cholinergic receptor ligand acetylcholine, and a variety of medications and endogenous compounds. 3′-AmNic was similarly linked to polyglutamate to serve as coating antigen for ELISA assay.

6-Carboxymethylureido nicotine

(6-CMUNic) was synthesized and conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) as previously reported, with the following modifications, for immunization of rats or bovine serum albumin (BSA) for use as coating antigen in ELISA assay [20]. BSA or KLH (ThermoFisher Scientific) 2.8 mg in 0.1 M MES buffer pH 4.5 was combined with CMUNic and N-ethyl-N′-(3-dimenthlyaminopropyl)carbodiimide HCl (EDC) in MES buffer at a final concentrations of CMUNic 5.1 mM and EDC 52 mM. Reactants were mixed for 3 h at room temperature and dialyzed against phosphate buffered saline for 6 h at 4°C. This procedure improved the haptenation ratio for the BSA conjugate, as measured by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry to >20;1. Immunization of rats with 6-CMUNic-KLH has been previously reported to produce high concentrations of high affinity (Kd = 27 nM) nicotine specific antibodies with cross-reactivity to other compounds similar to that noted above for 3′-AmNic-rEPA.

2. 3 Immunization

Rats were vaccinated i.p. with 25 ug of immunogen in 0.4 ml complete Freund’s adjuvant on day 0 and boosted with 25 ug of immunogen in 0.4 ml incomplete Freund’s adjuvant on days 21 and 42. Blood was obtained and experiments were performed 1–2 weeks after the final vaccine dose. Control animals were immunized with unconjugated carrier protein plus adjuvant.

2. 4 ELISA and radioimmunoassay

The drug-binding specificity of anti-1′-SNic-KLH antibodies was analyzed by competitive ELISA using 1′-SNic-OVA as the coating antigen to avoid cross-reactivity with the carrier protein [19]. The affinity for nicotine of antibodies from rats vaccinated with 1′-SNic-KLH, and their concentration in the serum, were analyzed by soluble radioimmunoassay [21]. The epitope recognition specificity of antibodies generated by each of the 3 nicotine immunogens was evaluated by ELISA with antisera plated against wells each containing a single immunogen conjugated to a single carrier protein. For example, antiserum from rats immunized with 3′-AmNic-rEPA was reacted in wells coated with 3′-AmNic-polyglutamate and also with the non-corresponding antigens 6-CMUNic-KLH or 1′-SNic –OVA [17].

2.5 Evaluation of 1′-SNic conjugation conditions

Molar haptenation ratios (moles of hapten bound per mole of protein) were determined by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. The 1′-SNic-KLH conjugates could not be analyzed by mass spectrometry because of their size, and were analyzed instead by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel. Nicotine distribution was studied in rats anesthetized with fentanyl/droperidol. Nicotine 0.03 mg/kg (weight of the base, 0.185 μmol/kg) was administered through a jugular venous catheter over 10 sec, and rats were sacrificed by decapitation 3 min later for collection of serum and brain. Nicotine concentrations were measured by gas chromatography [22]. Brain concentrations were corrected for brain blood content [23].

2.6 Statistical analysis and calculations

Serum and brain nicotine concentrations were compared by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-test. The geometric mean was used to characterize antibodies from rats vaccinated with 1′-SNic-KLH because of the range and non-normal distribution of values. Molar serum antibody binding site concentrations were calculated using a molecular weight of 75 kDa per binding site (2 sites per IgG). The saturation of antibody with nicotine in the serum of vaccinated rats was calculated as the ratio of the mean molar serum nicotine concentration to the mean molar serum antibody binding site concentration.

3. Results

3.1 1′-SNic-BSA

Conjugation of the mercaptan resulting from TCEP reduction of 1′-SNic to maleimide-activated BSA was used to optimize reaction conditions and to confirm haptenation since this can be accomplished using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for BSA but not for the larger KLH. Conjugation using 1′-SNic:BSA reaction molar ratios of ≥30:1 yielded molar protein haptenation ratios of approximately 20:1 (moles of 1′-SNic bound to BSA) while lower reaction ratios produced haptenation ratios of <10:1. However ELISA titers after immunization showed little difference among the various reaction conditions, and these conjugates were only marginally effective in retaining nicotine in serum or reducing nicotine distribution to brain (data not shown).

3.2 1′-SNic-KLH immunogenicity

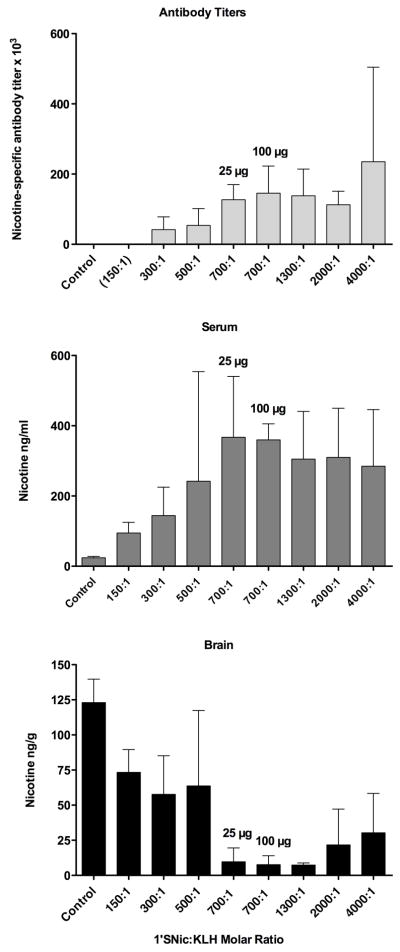

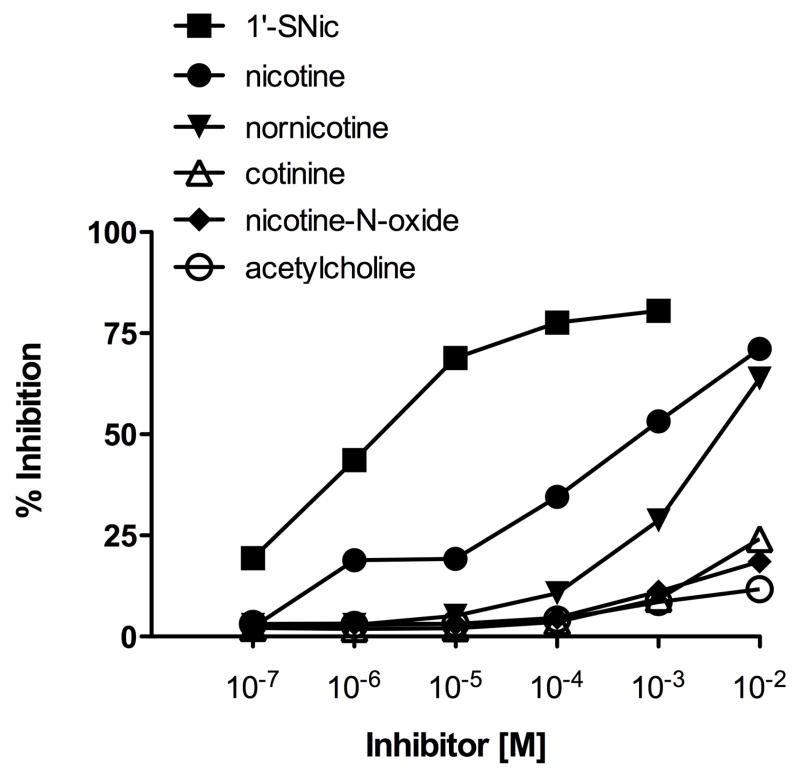

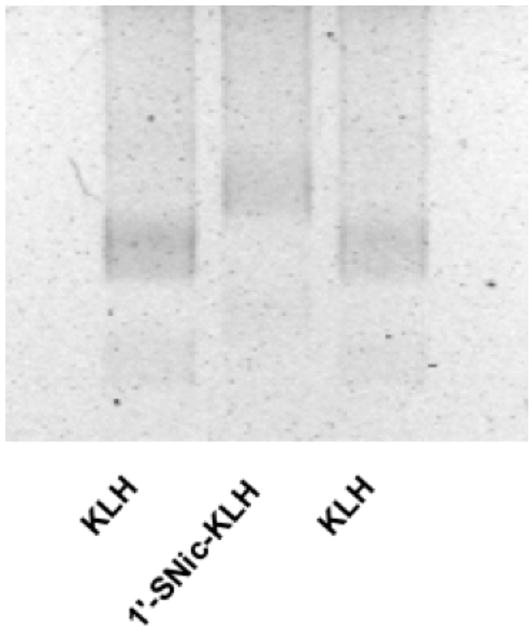

Reduced 1′-SNic was conjugated to maleimide-activated KLH using molar ratios approximately 10-fold higher than those used for BSA because of the larger size and surface area of KLH. Conjugation was confirmed qualitatively by showing altered migration on agarose gel (Fig 2). ELISA titers were highest with molar ratios of 700:1 (Fig 3). The antibodies elicited by 1′-SNic-KLH had their highest relative affinity for the 1′-SNic hapten but also had substantial affinity for nicotine, somewhat lower affinity for the active but minor nicotine metabolite nornicotine, and little affinity for the inactive nicotine metabolites cotinine and nicotine-N-oxide, or the endogenous nicotinic receptor ligand acetylcholine (Fig 4). Characterization of antibodies from rats vaccinated with 1′-SNic-KLH showed a high affinity for nicotine (geometric mean Kd = 12 nM) and high serum antibody concentration (mean 210 μg/ml = 1.4 μM IgG = 2.8 μM binding sites), but with considerable variability in both measures (Table 1). The Kd of 1′-SNic-KLH antiserum for nicotine determined by RIA was substantially lower than the corresponding IC50 value from ELISA because the IC50 presumably reflects antibody avidity for the highly haptenated 1′-SNic-BSA conjugate used as the coating antigen while the Kd reflects the antibody affinity for soluble nicotine.

Figure 2.

1% Agarose gel of unconjugated maleimide-activated KLH (outer lanes) and 1′-SNic-KLH synthesized using a 700:1 molar hapten:protein ratio (middle lane) showing a change in mobility with conjugation.

Figure 3.

Efficacy of 1′-SNic-KLH synthesized using a range of conjugation reaction molar hapten:protein ratios. Top, nicotine-specific antibody titers (mean±SD) in vaccinated rats. Middle, retention of nicotine in serum; Bottom, nicotine distribution to brain 3 minutes after i.v. administration of 0.03 mg/kg nicotine (n=3 per group except n=6 for 700:1–25 ug group). Efficacy increased up to a reaction molar ratio of 700:1 but not with higher ratios.

Figure 4.

Ligand cross reactivity of antiserum from rats vaccinated with 1′-SNic-KLH determined by competition ELISA.

Table 1.

Characterization of serum antibodies in rats vaccinated with 1′-SNic-KLH.

| Rat | Titer × 103 | Kd (nM) | Serum Antibody (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4913 | 15 | 240 | 320 |

| 4914 | 28 | 8.3 | 46 |

| 4915 | 142 | 16 | 360 |

| 4917 | 56 | 33 | 1270 |

| 4918 | 157 | 2.4 | 160 |

| 4919 | 69 | 2.5 | 66 |

| 4920 | 132 | 6.4 | 230 |

| Geometric mean | 65 | 12 | 210 |

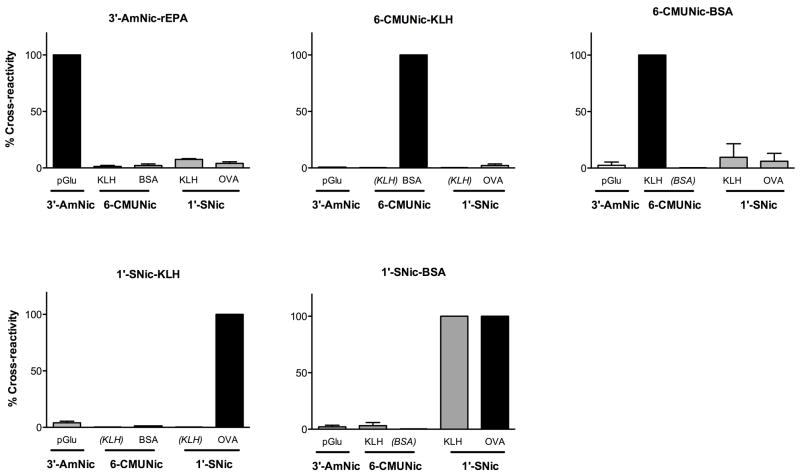

Comparison of the epitope recognition specificity of antibodies generated by the 3 nicotine immunogens showed that each had a different and highly specific pattern of binding, indicating that they recognize different epitopes on the nicotine immunogen. ELISA titers for each antiserum were highest when plated against coating antigens derived from the corresponding hapten (Table 2). Antiserum from rats immunized with 3′-AmNic-rEPA showed substantial cross-reactivity with the coating antigen 1′-SNic-BSA and moderate cross reactivity with the coating antigen 1′-SNic-KLH. Therefore a third coating antigen 1′-SNic-OVA was synthesized and cross-reactivity was low (3%). For all other combinations of antiserum and coating antigen, cross reactivity was <3% (Fig 5). 6-CMUNic-BSA antiserum showed modest cross-reactivity with the 1′-SNic coating antigens but 6-CMUNic-KLH antiserum did not.

Table 2.

Immunogen cross-reactivity, titers × 103. See Figure 5 for cross-reactivity expressed as percentiles.

| Antiserum | ELISA Coating Antigen * |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3′-AmNic

|

6-CMUNic

|

1′-SNic

|

|||

| pGlu | KLH | BSA | KLH | OVA | |

| 3′-AmNic-rEPA | 148 ± 25 | 2 ± 1 | 3 ± 2 | 11 ± 1 | 5 ± 1 |

| 6- CMUNic-KLH | 1 ± 0 | ------ | 223 ± 60 | ------ | 4 ± 3 |

| 6-CMUNic-BSA | 3 ± 4 | 146 ± 16 | ------ | 13 ± 16 | 8 ± 1 |

| 1′-SNic-BSA | 2 ± 1 | 2 ± 3 | ------ | 78 ± 16 | 78 ± 1 |

| 1′-SNic-KLH | 3 ± 2 | ------ | 0 ± 0 | ------ | 51 ± 11 |

Coating antigens consisted of the indicated haptens (3′-AmNic, 6-CMUNic or 1′-SNic) conjugated to carrier proteins polyglutamate (pGlu), keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH), bovine serum albumin (BSA) or ovalbumin (OVA).

Figure 5.

Immunogen cross reactivity ELISA assay. Antisera from vaccinated rats were plated against nicotine haptens conjugated to various carrier proteins. Panel titles indicate the antiserum and horizontal axis labels indicate the coating antigen. Titers are expressed as % of control with 100% (dark bars) representing the titer obtained for each immunogen plated against the corresponding coating antigen containing the same hapten. See Table 1 for corresponding ELISA titers expressed as absolute values.

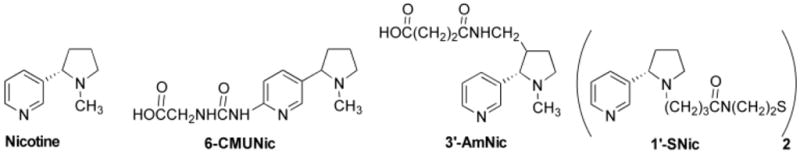

3.3 1′-SNic-KLH effects on nicotine distribution

Vaccination with 1′-SNic-KLH markedly enhanced nicotine retention in serum and reduced nicotine distribution to brain (Fig 3). Pharmacokinetic efficacy increased with 1′-SNic:KLH molar ratios in the reaction mixture of up to 700:1 but did not improve further with higher ratios. Because group size (n=3) was small for most conditions, statistical comparison of groups was not done and the data were only used to select a promising reaction molar (700:1) reactant ratio for further study. 1′-SNic-KLH immunogen synthesized using a reactant ratio of 700:1 and administered at a dose of 25 ug increased the retention of nicotine in serum by over 14-fold and reduced nicotine distribution to brain by 92%. Two doses of 1′-SNic-KLH, 25 and 100 ug/injection at the 700:1 reactant ratio produced similar ELISA titers and effects on nicotine distribution. The effects of 1′-SNic-KLH on nicotine distribution were comparable to those of 3′-AmNic-rEPA or 6-CMUNic (Fig 6). A nicotine dose of 0.03 mg/kg (0.185 μmol/kg) resulted in serum nicotine concentrations of 21±5 ng/ml (0.13 nmol/ml) in control animals and 367±173 ng/ml (2.3 nmol/ml) in rats vaccinated with 1′-SNic-KLH. Serum antibody in vaccinated rats was highly (81%) saturated with nicotine.

Figure 6.

Nicotine retention in serum and distribution to brain in vaccinated rats (mean±SD, n=6 per group). The 1′-Snic-KLH immunogen was as effective as the other immunogens. * p <0.05 compared to control.

4. Discussion

The clinical feasibility of co-administering 2 or more unrelated immunogens in a single vaccine is well established, with the use of combination vaccines such as measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) or diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus (DPT) [24]. Antibody responses to the individual immunogens are not compromised compared to administration of the individual components singly or at different times. This capacity reflects the ability of the immune system to respond to multiple concurrent immunologic challenges. The possibility of designing multiple immunologically distinct immunogens from very small molecular targets extends this concept from microbial antigens to a potentially wide range of drugs or chemicals.

The 1′-SNic hapten design was intended to present structural aspects of nicotine for immune recognition that differ from those presented by 3′-AmNic or 6-CMUNic. The principal structural feature used to accomplish this was the 1′ linker position, already shown to be effective for generating nicotine-specific antibodies [12]. A different linker structure and linkage chemistry were also incorporated since these can contribute to hapten recognition [20]. The distinct clonal responses to the 3 immunogens were demonstrated by the low ELISA cross-reactivity when antiserum elicited by each was analyzed using the other 2 immunogens as the solid phase coating antigen. Nonspecific cross-reactivity was observed between 6-CMUNic-KLH or 3′-AmNic-rEPA antisera and 1′-SNic-BSA coating antigen, attributable to the BSA carrier protein since cross-reactivity was much lower when 1′-SNic-OVA was used as the coating antigen. The distinct ELISA profiles of the 3 antisera establish that the antibody responses to these 3 immunogens were largely mediated by separate and non-overlapping populations of B cells.

Many nicotine immunogen designs have been reported utilizing a variety of linker positions, linker compositions, structurally modified haptens, and carrier proteins [15, 25–28]. It is clear that many of these can serve as effective immunogens as measured by the ability to produce nicotine-specific antibodies. The novel information in the current report is in the demonstration that 1′-SNic-KLH is immunologically distinct from previously studied immunogens, and that designing three immunologically distinct immunogens from a very small molecule such as nicotine is feasible. Because the 3 immunogens differ in multiple ways it is not clear, and was not the focus of this study to determine, which aspect or aspects of nicotine immunogen structure are critical for establishing its immunologic identity. It is possible that hapten, linker and protein all contributed since epitopes for protein antigens commonly include 10–25 amino acids, which is substantially larger than the nicotine hapten-linker alone [29]. It is likely that linker structure contributes to the 1′-SNic-KLH epitope since the full hapten (nicotine-linker) was considerably more potent than nicotine alone as an inhibitor of nicotine binding in ELISA assay. The same preference for hapten-linker over nicotine was previously reported for antibodies generated by 6-CMUNic [20]. Further study of these contributors to immunogen identity may suggest whether the individual components can be further modified to design additional immunologically distinct or more potent nicotine immunogens.

The efficacy of nicotine vaccines for reducing nicotine distribution to brain in rats has proven to be a robust indicator of their efficacy in blocking addiction-like behaviors in rats [30], and appears to be related as well to their clinical efficacy for enhancing smoking cessation rates [6, 15]. The 1′-SNic-KLH immunogen showed efficacy in this pharmacokinetic model comparable to that of 3′AmNic-rEPA, an immunogen which has advanced to clinical trials [6]. Thus these differing immunogens not only elicit distinct antibody responses but each serves as a highly effective immunogen in rats. None of the immunogen designs used here appears to be most immunologically favorable in rats, in that all produced high antibody titers and a robust effect on nicotine distribution. This again supports the potential generality of this approach since it shows that a molecule the size of nicotine can be presented not just in different ways, but in 3 highly effective ways to the immune system.

1′-SNic-KLH per se was a highly effective immunogen as indicated by generation of antibodies with a high affinity for nicotine (Kd = 12 nM) and serum concentrations (mean 210 ug/ml) comparable to those of the most effective previously studied nicotine vaccines [15, 19, 26]. The high immunogenicity of 1′-SNic-KLH may reflect the efficiency of the SH-maleimide conjugation chemistry, which has also produced high haptenation ratios for methamphetamine and heroin protein conjugates and highly immunogenic vaccines [13, 14, 31]. Although the 1′ linker position used for 1′-SNic-KLH is adjacent to the 5′ position at which nicotine is oxidized to its major metabolite cotinine and could theoretically mask this site to compromise antibody specificity (allow antibody cross-reactivity with cotinine), antibodies elicited by 1′-SNic-KLH were highly selective for nicotine and showed negligible binding to cotinine or nicotine-N-oxide. The lower affinity binding of antibodies to nornicotine that was observed could be beneficial. Although serum nornicotine concentrations in smokers are low compared to those of nicotine, nornicotine is reinforcing in rats [32].

The 12 nM Kd of nicotine-specific antibodies generated by 1′-SNic-KLH was lower than the serum nicotine concentration in control rats, suggesting that antibody in the serum of vaccinated rats should be highly saturated by nicotine. This was confirmed by the considerable retention of nicotine in serum and the high (81%) calculated saturation or occupancy of serum antibodies with nicotine. This Kd is also lower than typical serum nicotine concentrations in smokers (10–60 ng/ml) suggesting that antibodies resulting from vaccination with 1′-SNic-KLH should also bind nicotine effectively in smokers provided that serum antibody concentrations are adequate.

A limitation of nicotine and cocaine vaccines, in both animals and humans, is the high variability in serum nicotine-drug-specific antibody concentrations they produce [6, 7]. Similar variability was observed with antibodies from 1′-SNic-KLH. In addition, there was variability in the Kd for nicotine, a parameter which has not been measured in most studies of addiction vaccines and which would be expected to contribute to variability in efficacy and clinical response. It will be of interest to determine whether subjects responding poorly to one nicotine immunogen might respond briskly to another, enhancing the overall likelihood of a satisfactory immune response to vaccination with multiple immunogens.

These data establish that it is possible to present a small molecule such as nicotine to the immune system through different hapten-linker-protein combinations such that each is recognized as a distinct epitope capable of eliciting distinct and non-overlapping immunological response. This approach provides a general and easily translated strategy for improving immunotherapy for nicotine addiction. A nicotine vaccine that uses the 3′-AmNic-rEPA immunogen showed preliminary evidence of efficacy for enhancing smoking cessation in a Phase II clinical trial, but recently failed to achieve its primary outcome for smoking cessation in a phase III clinical trial (personal communication Rafaat Fahim, Nabi Biopharmaceuticals), and another nicotine conjugate vaccine using a different linker, linker attachment position and carrier protein also recently failed to achieve its primary cessation endpoint a phase II clinical trial [8]. These results suggest that combination vaccines which recruit multiple distinct populations of B cells may be an important strategy going forward to improve vaccine immunogenicity. Combining immunogens could also prove applicable to the design of vaccines for other addictive drugs, or to vaccines directed against other small molecule haptens such as chemical toxins.

Acknowledgments

The 3′-AmNic-rEPA immunogen and rEPA carrier protein were gifts of Nabi Biopharmaceuticals. Internal standard for the nicotine assay was a gift from P Jacob (University of California, San Francisco). Supported by NIH grants DA10714, DA010714-13S1, and a Career Development Award from the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation (MP).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Moreno AY, Janda KD. Immunopharmacotherapy: vaccination strategies as a treatment for drug abuse and dependence. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;92:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pentel PR, Keyler DE, Kosten TR. Immunotherapies to treat drug addiction. In: Levine MM, editor. New Generation Vaccines. New York: Dekker; 2009. pp. 982–92. [Google Scholar]

- 3.LeSage MG, Keyler DE, Hieda Y, Collins G, Burroughs D, Le C, et al. Effects of a nicotine conjugate vaccine on the acquisition and maintenance of nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:409–16. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anton B, Salazar A, Flores A, Matus M, Marin R, Hernandez JA, et al. Vaccines against morphine/heroin and its use as effective medication for preventing relapse to opiate addictive behaviors. Hum Vaccin. 2009;5:214–29. doi: 10.4161/hv.5.4.7556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinsey BM, Kosten TR, Orson FM. Anti-cocaine vaccine development. Expert review of vaccines. 2010;9:1109–14. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatsukami DK, Jorenby DE, Gonzales D, Rigotti NA, Glover ED, Oncken CA, et al. Immunogenicity and smoking-cessation outcomes for a novel nicotine immunotherapeutic. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2011;89:392–9. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martell BA, Orson FM, Poling J, Mitchell E, Rossen RD, Gardner T, et al. Cocaine vaccine for the treatment of cocaine dependence in methadone-maintained patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:1116–23. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Interim analysis of an ongoing phase II study with nicotine vaccine shows primary endpoint not achieved. Cytos Biotechnology Press release. 2011 http://wwwcytoscom/defaultasp?id=1572.

- 9.Meijler MM, Matsushita M, Altobell LJ, 3rd, Wirsching P, Janda KD. A new strategy for improved nicotine vaccines using conformationally constrained haptens. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:7164–5. doi: 10.1021/ja034805t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll FI, Abraham P, Gong PK, Pidaparthi RR, Blough BE, Che Y, et al. The synthesis of haptens and their use for the development of monoclonal antibodies for treating methamphetamine abuse. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2009;52:7301–9. doi: 10.1021/jm901134w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson EC, Gunnell M, Che Y, Goforth RL, Carroll FI, Henry R, et al. Using hapten design to discover therapeutic monoclonal antibodies for treating methamphetamine abuse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:30–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.117150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isomura S, Wirsching P, Janda KD. An immunotherapeutic program for the treatment of nicotine addiction: hapten design and synthesis. J Org Chem. 2001;66:4115–21. doi: 10.1021/jo001442w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll FI, Blough BE, Pidaparthi RR, Abraham P, Gong PK, Deng L, et al. Synthesis of Mercapto-(+)-methamphetamine Haptens and Their Use for Obtaining Improved Epitope Density on (+)-Methamphetamine Conjugate Vaccines. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2011;54:5221–8. doi: 10.1021/jm2004943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stowe GN, Vendruscolo LF, Edwards S, Schlosburg JE, Misra KK, Schulteis G, et al. A Vaccine Strategy that Induces Protective Immunity against Heroin. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2011;54:5195–204. doi: 10.1021/jm200461m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maurer P, Jennings GT, Willers J, Rohner F, Lindman Y, Roubicek K, et al. A therapeutic vaccine for nicotine dependence: preclinical efficacy, and phase I safety and immunogenicity. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2031–40. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duryee MJ, Bevins RA, Reichel CM, Murray JE, Dong Y, Thiele GM, et al. Immune responses to methamphetamine by active immunization with peptide-based, molecular adjuvant-containing vaccines. Vaccine. 2009;27:2981–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keyler DE, Roiko SA, Earley CA, Murtaugh MP, Pentel PR. Enhanced immunogenicity of a bivalent nicotine vaccine. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:1589–94. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carroll FI, Dickson HM, Wall ME. Organic sulfur compounds. III. synthesis of 2-(substituted alkylamine)ethanethiols. J Org Chem. 1965;30:33–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pentel PR, Malin DH, Ennifar S, Hieda Y, Keyler DE, Lake JR, et al. A nicotine conjugate vaccine reduces nicotine distribution to brain and attenuates its behavioral and cardiovascular effects in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;65:191–8. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hieda Y, Keyler DE, Vandevoort JT, Kane JK, Ross CA, Raphael DE, et al. Active immunization alters the plasma nicotine concentration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:1076–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller R. Determination of affinity and specificity of anti-hapten antibodies by competitive radioimmunoassay. Methods of Enzymology. 1983;92:589–601. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)92046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacob P, Wilson M, Benowitz NL. Improved gas chromatographic method for the determination of nicotine and cotinine in biologic fluids. J Chromatog. 1981;222:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)81033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hieda Y, Keyler DE, VanDeVoort JT, Niedbala RS, Raphael DE, Ross CA, et al. Immunization of rats reduces nicotine distribution to brain. Psychopharmacology. 1999;143:150–7. doi: 10.1007/s002130050930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollard AJ, Edwards KM, Fritzell K. Rationalizing childhood immunization programs: The variation in schedules and use of combination vaccines. In: Levine MM, Dougan G, Good MF, Liu MA, Nabel GJ, Nataro JP, et al., editors. New Generation Vaccines. New York: Informa healthcare; 2010. pp. 430–42. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cerny EH, Levy R, Mauel J, Mpandi M, Mutter M, Henzelin-Nkubana C, et al. Preclinical development of a vaccine ‘Against Smoking’. Onkologie. 2002;25:406–11. doi: 10.1159/000067433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carrera MR, Ashley JA, Hoffman TZ, Isomura S, Wirsching P, Koob GF, et al. Investigations using immunization to attenuate the psychoactive effects of nicotine. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:563–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2003.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Villiers SH, Lindblom N, Kalayanov G, Gordon S, Baraznenok I, Malmerfelt A, et al. Nicotine hapten structure, antibody selectivity and effect relationships: results from a nicotine vaccine screening procedure. Vaccine. 2010;28:2161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanderson SD, Cheruku SR, Padmanilayam MP, Vennerstrom JL, Thiele GM, Palmatier MI, et al. Immunization to nicotine with a peptide-based vaccine composed of a conformationally biased agonist of C5a as a molecular adjuvant. Int Immunopharmacol. 2003;3:137–46. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(02)00260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayrose I, Shlomi T, Rubinstein ND, Gershoni JM, Ruppin E, Sharan R, et al. Epitope mapping using combinatorial phage-display libraries: a graph-based algorithm. Nucleic acids research. 2007;35:69–78. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roiko SA, Harris AC, Keyler DE, Lesage MG, Zhang Y, Pentel PR. Combined active and passive immunization enhances the efficacy of immunotherapy against nicotine in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:985–93. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.135111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreno AY, Mayorov AV, Janda KD. Impact of distinct chemical structures for the development of a methamphetamine vaccine. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133:6587–95. doi: 10.1021/ja108807j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bardo MT, Green TA, Crooks PA, Dwoskin LP. Nornicotine is self-administered intravenously by rats. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:290–6. doi: 10.1007/s002130051119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]