Abstract

Purpose

To describe the profile of chronic and aggressive periodontitis among Senegalese (West Africans) attending the Institute of Dentistry of Dakar.

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted with an inclusion period running from 2001 to 2008. The sample included 413 chronic periodontitis and 151 aggressive periodontitis cases, among them 299 males and 265 females selected from 2,274 records. A Student's independent t-test or Pearson chi-squared test was used for data analysis.

Results

The proportion of females with aggressive periodontitis was significantly higher than those with chronic periodontitis (64.9% vs. 40.4%, P<0.001). The aggressive periodontitis patients had an average age of 28.1±8.9 years, and had lost less than 3 teeth. Less than a third of them reported using a toothbrush. Attachment loss was as high as 8 mm and severe lesions had spread to an average of 12 teeth with maximum alveolar bone loss up to 80%. The chronic periodontitis patients had an average age of 44.9±14.0 and had lost on average less than 3 teeth. Nearly 75% used a toothbrush. Attachment loss was significantly higher and lesions were more extensive in the aggressive periodontitis. Chronic periodontitis is associated with risk factors such as smoking or diabetes mellitus in 12.8% versus 0.7% in aggressive periodontitis (P<0.001). Differences between the two groups for most clinical and radiographic parameters were statistically significant.

Conclusions

The profile of aggressive periodontist is characterized by more severe lesions than chronic periodontitis, whereas tooth loss experience is similar in both forms.

Keywords: Aggressive periodontitis, Chronic periodontitis, Epidemiology, Periodontal diseases, Risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease of the supporting tissues of the teeth caused by specific microorganisms or groups of specific microorganisms, resulting in progressive destruction of periodontal tissues [1]. The two main entities are chronic periodontitis (Fig. 1) and aggressive periodontitis (Figs. 2 and 3). In the last thirty years the role of plaque control has been reinforced as the only consistent determinant of periodontal disease. However, there have been several fundamental changes to the understanding of periodontal disease that have impacted this traditional concept. These changes can be summarized as the differential susceptibilities to the onset of disease, the prevalence of different severities of the disease, and the emerging links between periodontal disease and other medical diseases or conditions [2]. The risk factors are environmental, behavioral, or biological factors that have been confirmed in longitudinal studies to have a punitive impact on the disease process [3-8]. Several factors are identified as increasing the risk of developing periodontal disease [9,10]. The major risk factors for periodontitis are smoking, diabetes, and specific periodontal pathogens. Other potential factors, including the systemic diseases that impact host defenses, may play a role in the progression of the disease [11,12]. Although clinical attachment levels are considered the gold standard in periodontal diagnosis and outcome measurement, they do not reflect issues that may be important to patients. Quality of life issues such as pain and discomfort, changes in esthetics or function, costs of therapy, and tooth loss are seen by patients to be more relevant than attachment levels or probing depths [13,14]. Therefore, it must also be taken into consideration that functional impairment and psychosocial impact of periodontal diseases may reduce quality of life.

Figure 1.

Buccal view of chronic periodontitis among male 45 years with no systemic disease or risk factors showing attachment loss and a significant amount of local factors.

Figure 2.

Buccal view of an aggressive periodontitis case in a 21-year-old female with no systemic disease or risk factors, showing discrete inflammation of the gingiva and very few local factors with the presence of diastema.

Figure 3.

Panoramic radiograph of the same case in the previous figure (female, 21 years) showing alveolar bone levels, missing teeth, and the presence of alveolar bone defects.

Chronic periodontitis is a common disease and can occur in most age groups but is more common in adults and elders worldwide [15]. Its prevalence and severity increase with age [3,4,16]. Aggressive periodontitis is characterized by severe and rapid loss of periodontal attachment and may be more common in children and adolescents. In young individuals, the onset of these diseases is often circumpubertal. The primary features of aggressive periodontitis include a history of rapid attachment and bone loss with familial aggregation [1]. Subsequent linkage studies of African-American and Caucasian families suggest that there may be genetic and/or etiologic heterogeneity for aggressive periodontitis. Reported estimates of the prevalence of aggressive periodontitis forms in geographically diverse adolescent populations range from 0.1 to 15% [15,17]. Most reports suggest a low prevalence (0.2%), which is markedly greater in African-American populations (2.5%) [15]. Albandar and Tinoco [18] reported on many studies on chronic/aggressive periodontitis in different ethnic and socio-economic level groups, concluding that a higher prevalence and severity could be found among individuals having a Hispanic-Black ethnic background or lower socio-economic status. Also, as reported by Hirschfeld and Wasserman [19], McFall [20] and McLeod et al. [17], 78 to 84% of patients will experience at least minimal disease progression and tooth loss (average tooth loss, 0.5 to 1). No study has been conducted in Senegal to distinguish the clinical differences between the two main forms of periodontitis.

The objective of this study was to describe the clinical profile of aggressive and chronic periodontitis patients attending the Clinical Unit of Periodontics of the Institute of Dentistry at the University Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar (University of Dakar, UCAD), Senegal (West Africa).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective study based on records of patients in the service of Periodontics, Institute of Dentistry at UCAD from 2001 to 2008 was conducted.

Included were the records of patients diagnosed with chronic periodontitis or aggressive periodontitis. The records of patients with gingival diseases and those insufficiently informed or not incorporating panoramic radiograph were excluded. In all the cases, periodontitis diagnosis was based on the 1999 classification of the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) [1] and clinical and radiographic parameters. The localized or generalized type of periodontitis is not considered in this study but only the main form.

The following chart entries were used in this study: gender, age, risk factors (like smoking or presence or absence of diabetes mellitus), use of a toothbrush for oral hygiene, attachment loss, probing depth, number of teeth with a probing depth of 3 to 4 mm and ≥5 mm, number of teeth with an attachment loss of 3 to 4 mm and ≥5 mm, tooth mobility, tooth loss, and maximum alveolar bone loss. William's periodontal probe (Michigan O probe, Hu-Friedy Mfg. Co., Chicago, IL, USA) was the main instrument used at the Clinic of Periodontics of UCAD to assess attachment loss and probing depth. Assessment of the periodontal supporting tissues' status was based on clinical measurement of the distance from the cemento-enamel junction or free gingival margin to the bottom of pocket/sulcus at 4 or 6 sites per tooth (according to the charting sheet design at UCAD). Tooth mobility was assessed using the Mühlemann index [21]. The alveolar bone loss was quantified on panoramic radiographs using the Bjorn technique for assessment of alveolar bone level as described by Albandar and Abbas [22]. In Bjorn's technique, the distance between the alveolar crest and the crown tip of the tooth was expressed as a proportion of the total length of the tooth. A lens displaying 2X magnification was fixed to a light screen and used to examine all radiographs. In this study, the alveolar bone loss is expressed as a percentage by measurement on the proximal faces of the most affected tooth and corresponded to the distance from the cemento-enamel junction to the bottom of the bone lesion reported to the distance between cemento-enamel junction and the apex. The measurements were made by a single operator (S.Y.) using a transparent millimeter ruler and a dry-tipped compass. The reliability of measurements was tested on 50 images from randomly selected files, using the calculation of the intraclass correlation coefficient. The threshold of 60% (95% confidence interval) was considered sufficient in this study to conclude good agreement measures (usual threshold>70%) because of the non-uniform quality of the radiographs. The 3rd molars were excluded in this study.

The records of 2,274 periodontal patients from the Service of Periodontics at UCAD were reviewed for this study. Only periodontitis patients were included (n=637). Of these, 73 (11.5%) were excluded because their charts were unusable or X-rays were absent or unreadable (conservation defects). Thus, 564 records met the selection criteria including 413 chronic periodontitis (73.2%) and 151 aggressive periodontitis (26.8%).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS ver. 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. Independent t-tests or chi-squared tests were performed to compare the clinical aggressive and chronic periodontitis group. The statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

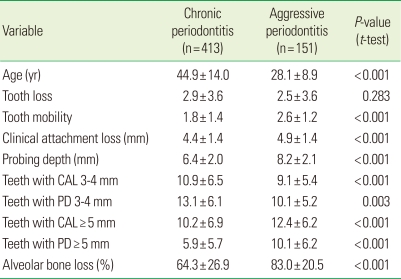

Comparative clinical parameters between chronic and aggressive periodontitis are given in Table 1. The sample included 299 males (53.0%) and 265 females (47.0%). The proportion of females with aggressive periodontitis was significantly higher than those with chronic periodontitis (64.9% vs. 40.4%, P<0.001).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical parameters from chronic periodontitis and aggressive periodontitis patients.

Values are presented as mean±SD.

CAL: clinical attachment loss, PD: probing depth.

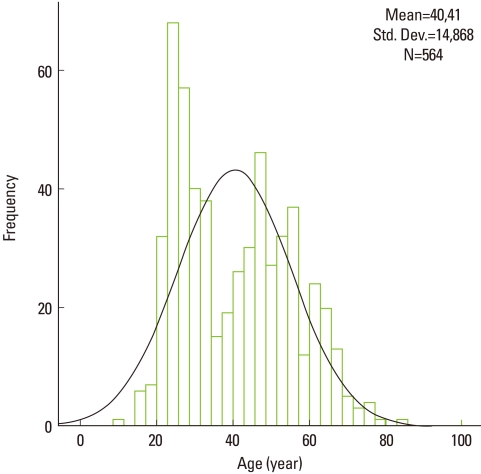

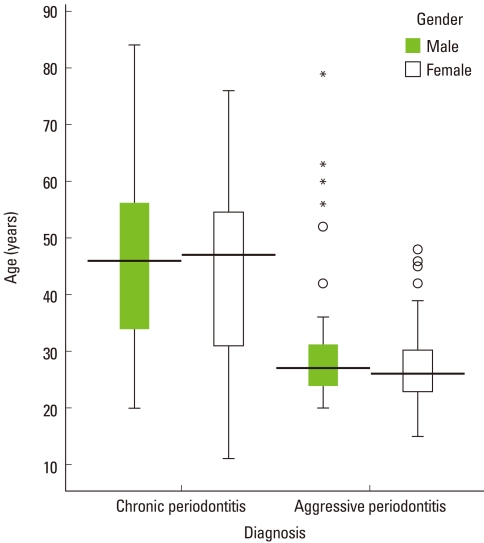

The age distribution showed two peaks around 25 and 45 years (Fig. 4). The age ranged from 11 to 84 and the mean was 40.4±14.9 years. The median in the center of the box plot diagrams shows a symmetrical distribution of age in both groups (Fig. 4). The median was lower for patients with aggressive periodontitis than those with chronic periodontitis. Higher variability of age among females with aggressive periodontitis and lower variability among males in the same group were observed. Several extreme values and outliers were noted in patients with aggressive periodontitis (Fig. 5). The toothbrush was used as a means of oral hygiene in 28.4% of patients with aggressive periodontitis and 71.6% of patients with chronic periodontitis (P=0.030).

Figure 4.

Histogram of age distribution among periodontitis patients showing two peaks. Std. Dev.: standard deviation.

Figure 5.

Box plot diagram of the age distribution by gender in patients with chronic periodontitis and aggressive periodontitis. A greater variability of age among females and several outliers were observed in the aggressive form.

Tooth loss experience was noted in 64.7% of the sample with a range of 1 to 22 teeth lost. The proportions were similar in both forms (65.4% vs. 62.9%, respectively, for chronic and aggressive forms) and no difference in mean tooth loss was seen (P=0.658) (Table 1). Patients with chronic periodontitis were more likely to have risk factors (smoking, diabetes mellitus) than those who had aggressive periodontitis (12.8% vs. 0.7%, P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to determine and compare the profile of the periodontitis patients consulted in the Periodontic Clinic at the UCAD in Dakar. As with most retrospective studies, the one conducted here is subject to many biases. The patients were probed by different undergraduate students and their instructors, all of whom bring their own biases to the clinic. Diagnoses may not have been accurately recorded. Thus, the results of this study cannot be generalized beyond this particular group of patients. Smoking (consumption, duration) and diabetes were insufficiently documented in the records of this study. The lack of a single medical record for each patient and computerization may have led to inadvertent duplication. The non-homogeneous quality of radiographs did not allow for correctly measuring the real value of the bone loss and radiographic data should thus be analyzed as an approximation or a trend. The causes of tooth loss were not determined because they were insufficiently documented in the clinical records. The absence of necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis is not surprising, as it is shown in the literature that periodontal necrotizing disease reaches mainly young children in Africa and those living in disadvantaged areas in regard to necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis [23]. The clinical feature of necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis occurs in most cases in young adults and the proportion of males and females suffering from the disease is the same. However, it seems that white people are significantly more likely to have this condition than blacks [24]. Necrotizing periodontal diseases occur with varying but low frequency (less than 1%) in North American and European children. It is seen with greater frequency (2 to 5%) in certain populations of children and adolescents from developing areas of Africa, Asia, and South America [25-27].

Although a predominance of males is noted, it is not representative of the influence of gender on the occurrence of periodontitis but is probably due to hazard. Studies are contradictory as to the predilection of periodontal disease according to gender [28,29]. However, females are more likely to be affected than males [30]. Albandar and Rams [8] refute the association between gender and aggressive periodontitis. Those most exposed to aggressive periodontitis were young adults around 25 years, as described in past classifications of periodontitis [31,32]. However, in this study the presence of extreme values and outliers for age shows that it is possible that some are due to errors in data entry. The data otherwise would confirm that age is not a reliable criterion for the diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis that can evolve at a more advanced age. Eliminating the age criterion is probably one of the most important innovations of the AAP 1999 consensus classification of periodontal diseases published by Armitage [1]. Initiation and progression of periodontal infections are clearly modified by local and systemic conditions called risk factors [9]. Significant risk factors known to be important today include diabetes mellitus (poor metabolic control) and cigarette smoking. These two risk factors markedly affect the initiation and progression of periodontitis, and attempts to manage these factors are now an important component of prevention and treatment of adult periodontitis. There are also background determinants associated with periodontal disease including gender, age and hereditary factors. Grossi et al. [3,4] showed the link between tobacco consumption (packages per year) and the severity of periodontitis. Also, Alpagot et al. [7] found a highly significant association between cigarette smoking, age, and attachment loss. A case-control study of 300 cases and 300 controls by Diallo et al. [23] in Senegal showed that the plaque index was significantly higher among smokers than nonsmokers with a very significant difference.

In a longitudinal study of 20 years follow-up in a group of individuals aged 15 to 60 years reported by Hugoson and Laurell [16], it was noted that chronic periodontitis affects people of all ages. Also, the prevalence and extent of periodontal destruction increases with age and inadequate oral hygiene. According to Albandar and Rams [8], the quality of oral hygiene and the presence of local factors such as calculus are not valid diagnostic criteria for aggressive periodontitis. The severity of aggressive periodontitis seems to be more related to the virulence of bacteria such as Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, while systemic or genetic factors are associated with chronic forms. The presence of a history of periodontal disease in families may be a predisposing factor for aggressive periodontitis. According to Fourel [33], one of the constant parameters in early-onset-periodontitis currently classified as aggressive periodontitis is the existence of a familial factor. This was difficult to identify solely on the basis of this study because the characteristics of the siblings of the patients were not recorded.

Goodson et al. [34] have presented evidence indicating that periodontal disease has dynamic states of exacerbation and remission and can be described in terms of patterns of progression and regression of the disease. Periodontitis can be distinguished by the rate of progression in different forms of the disease. In most patients, mean annual bone loss is less than 1 mm, while more susceptible people demonstrate rapid attachment loss and bone destruction [17]. Longitudinal studies on the progression of periodontitis indicate that the rate of periodontal tissue destruction is low and that advanced forms of the disease occur in comparatively few individuals and few tooth sites [16,35]. The periodontal lesions affect a large number of sites and took generalized and severe forms among subjects of both groups in our study. However, significantly greater amounts were found in aggressive periodontitis. This finding is in concordance with the current understanding of the progression of periodontal attachment loss.

There was no significant difference in tooth loss between aggressive periodontitis and chronic periodontitis in this study. Matthews et al. [14] showed in a study in Canada among 335 periodontitis patients that 20.6% had lost teeth. Periodontal disease accounted for 61.8% of the teeth lost, caries 24.8%, and all other causes accounted for 13.2%. Matthews et al. [14] reported that patients with the aggressive form of periodontitis likely accounted for the majority of the tooth loss in their study. Albandar et al. [36] in a multiracial controlled study over 6 years showed that 46 to 50% of individuals with aggressive periodontitis had lost at least one tooth. According to Machtei et al. [37], a possible mechanism that might explain this greater tooth mortality in these subjects is the likelihood that the dentist treating subjects with complex systemic conditions might prefer extraction over an elaborate treatment plan that might have preserved these teeth. Our findings show a high tooth loss experience among Senegalese, which may be due to poor economic status making full access to dental care and treatment difficult. They otherwise show the importance of improvements that should be made to the processing of medical records such as computerization in university dental institutes in developing countries like Senegal.

Clinical characteristics in chronic and aggressive periodontitis are markedly extensive and severe. The profile of aggressive periodontitis is characterized by more severe lesions than chronic periodontitis, whereas tooth loss experience is similar in both forms. Particular emphasis should be placed on the prevention and identification of patients at risk.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart TC. Genetic risk factors for early-onset periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1996;67:355–366. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.3s.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grossi SG, Genco RJ, Machtei EE, Ho AW, Koch G, Dunford R, et al. Assessment of risk for periodontal disease. II. Risk indicators for alveolar bone loss. J Periodontol. 1995;66:23–29. doi: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grossi SG, Zambon JJ, Ho AW, Koch G, Dunford RG, Machtei EE, et al. Assessment of risk for periodontal disease I Risk indicators for attachment loss. J Periodontol. 1994;65:260–267. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Löe H, Anerud A, Boysen H, Smith M. The natural history of periodontal disease in man. The rate of periodontal destruction before 40 years of age. J Periodontol. 1978;49:607–620. doi: 10.1902/jop.1978.49.12.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Löe H, Anerud A, Boysen H, Morrison E. Natural history of periodontal disease in man. Rapid, moderate and no loss of attachment in Sri Lankan laborers 14 to 46 years of age. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:431–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb01487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alpagot T, Wolff LF, Smith QT, Tran SD. Risk indicators for periodontal disease in a racially diverse urban population. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:982–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albandar JM, Rams TE. Risk factors for periodontitis in children and young persons. Periodontol 2000. 2002;29:207–222. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.290110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Genco RJ. Current view of risk factors for periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 1996;67(10 Suppl):1041–1049. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pihlstrom BL. Periodontal risk assessment, diagnosis and treatment planning. Periodontol 2000. 2001;25:37–58. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2001.22250104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinane DF. Periodontitis modified by systemic factors. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:54–64. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyle J, Gonzáles JR. Influences of systemic diseases on periodontitis in children and adolescents. Periodontol 2000. 2001;26:92–112. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2001.2260105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthews DC, McCulloch CA. Evaluating patient perceptions as short-term outcomes of periodontal treatment: a comparison of surgical and non-surgical therapy. J Periodontol. 1993;64:990–997. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.10.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthews DC, Smith CG, Hanscom SL. Tooth loss in periodontal patients. J Can Dent Assoc. 2001;67:207–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albandar JM. Epidemiology and risk factors of periodontal diseases. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49:517–532. v–vi. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hugoson A, Laurell L. Impact des données épidémiologiques sur les stratégies thérapeutiques en parodontie. J Parodontol Implant Orale. 2000;19:103–116. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLeod DE, Lainson PA, Spivey JD. The effectiveness of periodontal treatment as measured by tooth loss. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128:316–324. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albandar JM, Tinoco EM. Global epidemiology of periodontal diseases in children and young persons. Periodontol 2000. 2002;29:153–176. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.290108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirschfeld L, Wasserman B. A long-term survey of tooth loss in 600 treated periodontal patients. J Periodontol. 1978;49:225–237. doi: 10.1902/jop.1978.49.5.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McFall WT., Jr Tooth loss in 100 treated patients with periodontal disease. A long-term study. J Periodontol. 1982;53:539–549. doi: 10.1902/jop.1982.53.9.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mühlemann HR. Tooth Mobility. The measuring method, initial and secondary tooth mobility. J Periodontol. 1954;25:22–29. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albandar JM, Abbas DK. Radiographic quantification of alveolar bone level changes. Comparison of 3 currently used methods. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:810–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb02235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diallo PD, Benoist HM, Diallo-Seck A, Diouf A, Ka NM, Sembene M. Epidemiological study of acute necrotizing gingivitis in Senegalese children. J Parodontol Implant Orale. 2005;24:169–175. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melnick SL, Roseman JM, Engel D, Cogen RB. Epidemiology of acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. Epidemiol Rev. 1988;10:191–211. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith BW, Dennison DK, Newland JR. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome: implications for the practicing dentist. Va Dent J. 1986;63:38–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taiwo JO. Severity of necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis in Nigerian children. Periodontal Clin Investig. 1995;17:24–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Contreras A, Falkler WA, Jr, Enwonwu CO, Idigbe EO, Savage KO, Afolabi MB, et al. Human Herpesviridae in acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis in children in Nigeria. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1997;12:259–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1997.tb00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glickman I. Periodontal disease. N Engl J Med. 1971;284:1071–1077. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197105132841906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kinane DF. Susceptibility and risk factors in periodontal disease. Ann R Australas Coll Dent Surg. 2000;15:51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baer PN. The case for periodontosis as a clinical entity. J Periodontol. 1971;42:516–520. doi: 10.1902/jop.1971.42.8.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ranney RR. Classification of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 1993;2:13–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1993.tb00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki JB, Charon JA. Current classification of periodontal diseases. J Parodontol. 1989;8:31–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fourel J. Periodontosis: a periodontal syndrome. J Periodontol. 1972;43:240–255. doi: 10.1902/jop.1972.43.4.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goodson JM, Tanner AC, Haffajee AD, Sornberger GC, Socransky SS. Patterns of progression and regression of advanced destructive periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1982;9:472–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1982.tb02108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindhe J, Okamoto H, Yoneyama T, Haffajee A, Socransky SS. Longitudinal changes in periodontal disease in untreated subjects. J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16:662–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1989.tb01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albandar JM, Brown LJ, Löe H. Dental caries and tooth loss in adolescents with early-onset periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1996;67:960–967. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Machtei EE, Hausmann E, Dunford R, Grossi S, Ho A, Davis G, et al. Longitudinal study of predictive factors for periodontal disease and tooth loss. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;26:374–380. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.1999.260607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]